4

Push through Boundaries & let your Subject Guide you

One of the most challenging aspects of documentary photography is learning to push through the invisible boundaries that stand between you and your subject, whether you are studying the agitated gestures of a stranger on the subway or following a subtle expression of love between your child and her pet. What’s important to keep in mind is that these boundaries are just permeable dotted lines, and they exist only in your mind. Learning to move through these boundaries respectfully and in sync with your subject will help you portray your subject in an authentic and more intimate way.

The legendary documentary photographer Robert Capa once said, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough.” It’s true. And it’s not just about the positioning of your feet or the reach of your lens. It’s about tightening the distance between you and your subject— opening your mind and minimizing the boundaries. The best way to improve your documentary photography skills is to focus first (and frequently) on the people closest to you, because they trust you and feel at ease in your presence. The boundaries between you are minimal, or at least more permeable. Set your zoom lens aside, and try creeping in close with a wide-angle lens until you bump into that invisible barrier of discomfort—of getting too close—and then just click. There’s no need to hold yourself back, unless your subject requests that you do.

As you begin to follow and photograph people you may not know, you must first push through the invisible boundary surrounding yourself by being open. Deflate your ego, assumptions, personal beliefs, and misconceptions, and let your curiosity guide you. Move toward your subject with questions and a genuine desire to learn, making it clear that you are following his or her lead through the experience. If your subject is seated on the ground beside chickens or standing knee-deep in a rice field, drop your inhibitions and meet them where they are. Make no judgments. Be kind and respectful. Trust your subject, and your subject will begin to trust you.

Another way to get comfortable pushing through invisible boundaries is to make images of diverse people with a mobile camera on a daily basis. Whether we like it or not, our cameras serve as physical obstructions— a visible barrier between the photographer and subject. Minimizing the size and weight of your camera or lens makes you more agile and less intimidating to your subject, particularly in the eyes of people you don’t know well, or strangers (if you’re experimenting with street photography, for example). Get comfortable holding your camera and taking pictures in a variety of unfamiliar environments. Introduce yourself to someone you’d like to photograph, ask questions, and build a rapport to establish a connection with your subject before you even think about lifting the camera to your eye. Let yourself be open and get comfortable feeling vulnerable. The more you push yourself through your own personal boundary, the closer you get to your subject.

In this chapter, I’ll share a handful of personal documentary project experiences. I hope they reveal the vulnerability, curiosity, and awe I often feel in the presence of my subjects, and I hope they inspire you to trust your intuition and to be courageous in revealing stories that need to be seen.

Connect with People You Respect & Admire

Mama Lucy Kamptoni, founder of Shepherds Junior School, stands before a nursery school class housed in a room behind her home in Arusha, Tanzania. She started Shepherds Junior School in this chicken-coop-turned-classroom with money she saved from her small poultry business.

I find that most of my favorite photographs have been made in situations when I showed up simply because I believed in the goodness of my subjects and the positive impact of their actions. This is the work I assign myself. Your ability to document and share an experience in a visually compelling way through your photographs is a gift. Think about ways in which you can use that gift to shine a light on and garner support for people you respect and admire and who are doing inspiring work. Volunteer your time and photography skills to individuals or non-profit organizations doing work you find moving and fulfilling. The photography that comes of this, the work of your heart, may eventually attract publishers and an audience beyond your reach, which in turn can help advance awareness and support for your subjects.

On April 24, 2009, my friend and project partner Jen Lemen and I were named the grand prize winners of the Name Your Dream Assignment photography competition sponsored by Lenovo and Microsoft—a competition that attracted more than 2,500 submissions from photographers across the United States—for our “Picture Hope” submission. We traveled to Rwanda, Tanzania, and Nepal to shine a light on icons of hope— genocide survivors, courageous change makers, old visionaries, and new immigrants.

Following are select images from two photo essays from my “Picture Hope” assignment, inspired by two women I respect and admire: Mama Lucy Kamptoni, founder of Shepherds Junior School in Arusha, Tanzania, and Renu Bagaria, founder of Koseli School in Kathmandu, Nepal. Both women followed their passion to provide education to impoverished children in their communities, children who might not have otherwise had an opportunity to go to school. I challenge you to find and focus your lens on someone you respect and admire, and shine a light on the impact of their good work.

Students from first through fifth grade at Shepherds Junior School gather in the campus courtyard at the end of each day to hear final announcements, share songs, and say farewell before boarding the buses to return to their homes throughout the Kimandolu area of Arusha, Tanzania.

Shepherds Junior School, Arusha, Tanzania

Shepherds Junior School in Arusha, Tanzania began as a seed of hope in the heart of its founder, Mama Lucy Kamptoni, in 2003. Using what few resources she had—income from her modest poultry business, rented land beside her home, a chicken coop she converted into a classroom, and a strong dose of faith—Mama Lucy grew that seed of hope, with support from non-profit organization Epic Change, into a primary school that now educates hundreds of students and provides many children a caring place to call home.

Thanks to Epic Change, co-founded by Stacey Monk and Sanjay Patel, and their innovative use of social media tools such as Twitter to inspire social change, supporters from around the world contributed funds to help introduce technology and establish Internet connectivity for Shepherds Junior School. During a month-long visit to the school in October 2009, Epic Change, with support from volunteers AJ and Melissa Leon, implemented a social media curriculum and worked with eager teachers and fifth-grade students to establish online communications and information sharing using blogs, email, and Twitter. Since that experience, teachers and students have continued to cultivate relationships with supporters from around the world.

Connect

Learn more:

Shepherds Junior School: www.shepherdsjr.com

Epic Change: www.EpicChange.org

A curious young student at Shepherds Junior School in Arusha, Tanzania makes his first images with a digital camera.

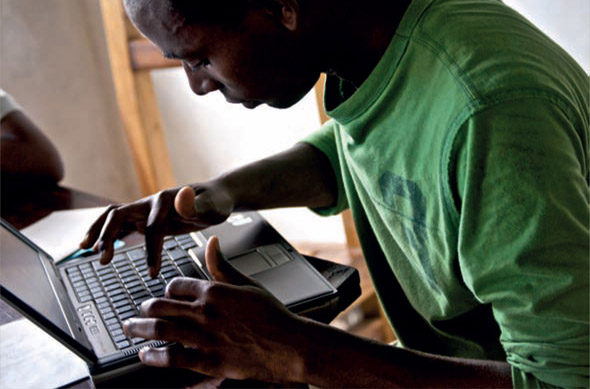

Sanjay Patel, chairman and co-founder of Epic Change, introduces fifth-grade students to the concept of email on one of the school’s new laptops.

Luther exercises his interview skills with fellow classmates using a digital audio recorder during his lunch break between lessons.

Fifth-grade student Rodgers stands proudly before visitor Madeleine Lemen to have his picture made in recognition of completing his technology introduction class. Having successfully set up his Twitter account and unleashed his first set of tweets, he bears a paper crown with the Twitter logo.

Teacher Sylvester carefully taps out his first blog post on one of fourteen laptop computers donated to Shepherds Junior School by Epic Change.

Headmaster Sylvano Nanyaro and a student welcome visitors in the school’s administrative office.

Koseli School, Kathmandu, Nepal

Hundreds of thousands of children are not attending school in Nepal. Many of these children are working as domestic help and in adult establishments as a means of survival. On the streets of Kathmandu, you will find children gambling and begging for money, as their families cannot afford to send them to school. Education is beyond their reach as they struggle to provide the basics of food, shelter, and clothing.

Though poverty and lack of access to primary education is a massive problem for Nepal, Renu Bagaria felt moved to do something, so she started small by gathering five of her friends in 1997 to collectively send five children from the slums to school, and supported them for ten years. Inspired by the performance of those five children and their ability to enter mainstream society as well-educated young adults, Renu was moved to do more. In 2007, she founded a free evening school for 22 students, but soon realized that the needs of the children exceeded what she could provide. Many of the children were still gambling on the streets during the day, and few had eaten before they arrived to school in the evenings. Within just three years, Renu increased her network of donors and expanded her efforts to open the doors of Koseli School, a free, comprehensive day school providing academic studies; exposure to the arts including crafts, photography, drama, and dance; healthy meals; and basic medical support for the poorest of the poor children living in Kathmandu’s largest slums.

Reliant upon financial donations, Koseli School has steadily grown to support more than 100 children, increasing its admissions to keep up with the demands that consistently exceed available resources. Following an onsite interview at the school, they visit each child’s home to assess the family’s level of need, and get a sense for the parent or guardian’s commitment to send the child to school each day. Because demand always exceeds what the school can accommodate, Koseli may only be able to accept one child from a family with several children, offering hope that that one child will become empowered and inspired to find a career path and help support his or her family in the future. Renu says there is so much more that needs to be done. But she believes Koseli is a hopeful place to start.

A view of Bagmati area in Kathmandu, home to numerous Koseli School students. During the rainy season, the river pictured floods many homes, making it difficult for children to walk to school.

Connect

Learn more about Koseli School

www.nepalkoseli.blogspot.com

Renu Bagaria, founder of Koseli School, visits student Upendra at his home in Jadibuti area of Kathmandu.

Koseli School students and brothers Sanjeev and Sudip and friend Hari enjoy playing with a kitten on the family bed in their one-room home.

Koseli School students and close friends Manju, Srijana, and Manisha show off their henna designs while on a field trip to the Central Zoo in Kathmandu.

A young Koseli School student admires teacher Sapana.

Teacher Nabeena, also a dancer and choreographer, shares a lesson with eager young students.

Teacher Krishna (left) guides students as they tour the Central Zoo in Kathmandu.

Follow Your Intuition & Trust Your Instincts

Documentary photography requires you to follow your intuition and trust your instincts, because life moves by the second. During the shooting process alone, you will make rapid decisions about what to shoot, where to stand, how to expose, where to focus, and what to reveal in each image you make, and if you’re truly focused on the moment, as you should be, an analytical thought process won’t have the capacity to keep up. Loosen your grip, and let your intuition guide you. Trusting your instincts about your subject, the setting, and the situation forces you to be open and vulnerable and to take risks. You could move in too close. You could make your subject uncomfortable. You could step on something. You could miss a non-verbal cue. You could cross a boundary. But you likely won’t have time to stop and think about these things or wait for permission. Just follow your intuition and trust your instincts. If you take a risk and make a mistake, apologize and seek forgiveness.

Following my intuition has never come easily for me, though I’ve recognized the quiet voice inside urging me in various directions. I often silenced it because logic or an analytical thought process served me well for so many years. I could talk myself out of actions that might result in an unsuccessful outcome. I limited my risks to minimize the need for me to trust my intuition, drawing an invisible line around “the knowns” in my life, and stayed comfortably within that boundary for many years.

But, particularly over the past several years, I’m finding that the more often I cross that boundary and follow my intuition, my requirements for trust increase. I have to trust that the person who took my passport will give it back to me. I have to trust that the driver will take me to a destination I can’t pronounce or find on a map. I have to trust that the people I meet and photograph will accept me with open arms. I have to trust that my children are safe when I’m far from home.

But most importantly, I’ve learned that I have to trust myself—to trust my intuition, well ahead of anything that my mind might process and direct. I’ve learned that I don’t need a lot of evidence or extensive analysis to guide me. Naturally, there are times when I feel weak and wonder if my intuition is worthy of such trust, when the calculations of my mind don’t equal that of my heart. But I can’t recall a time when my intuition has failed me. Even when it’s led me to a place I’ve never been.

Mutoni sits beside family friend William after breakfast. William talks about life as a Rwandan refugee in Uganda and his return to his father’s homeland with his mother and 19 brothers and sisters in 1995 following the genocide. Neighbors enter and exit through the open door.

New mother Jai Dhara BK and her baby attend a Sahahara Mothers’ Group monthly meeting, supported in part by the CARE CRADLE program, high in the hills of Doti District in the far west region of Nepal. Women from the community gather to learn about maternal and newborn care and to provide cooperative financial support for one another. © Stephanie Calabrese Roberts/CARE.

Be Kind, Respectful, & Aware of Your Presence

Working on the first day of my assignment for CARE in the far west region of Nepal on July 28, 2010, I was asked to document their CRADLE Support Project focused on mothers and newborns. Four of us climbed up a wooden ladder to reach a new mother and her six-day old baby, tucked away in the loft of the Nagri family’s dried-clay home high in the hills of Chhatiwan (Doti District). When I saw young Dharma, age 17, sitting quietly beside her newborn swaddled snugly in layers of colorful wraps, I felt so humbled and grateful to have been invited into such an intimate space. “Namaste,” I said softly, looking into Dharma’s eyes.

Quickly taking in her presence and the vivid colors and details of the space, I adjusted my ISO setting to accommodate for the dim setting (with just one stream of harsh light through a small window), pointed my external mount flash to fire at the wall behind me to bounce and soften the light, and chose a moderate aperture setting to let in as much light as possible while retaining some focus on the detailed background elements. I was sensitive to the fact that Dharma and her baby were seated comfortably on layers of blankets, so I positioned myself to find the right perspective.

As I began to make my first few images, I sensed that Dharma was shy and hesitant to move. The baby was sleeping, so there was little for her to do but focus on the four of us and the sounds of my clicks. Conscious of my presence and eager to minimize it, I turned on my digital audio recorder and asked my partner Jen to interview Dharma about her birth experience. I needed conversation in the space to draw the focus away from my camera. When Dharma began to answer questions in Nepali, I could see that she was beginning to feel more at ease with us, but I didn’t feel that I could accurately portray the loving emotion I knew she felt for her sleeping newborn. “Can you ask her to pick up the baby?” I asked Mukesh, my primary CARE host. At this, Dharma smiled toward her sleeping son and reached down to lift him with such tenderness. I quickly got down on the dirt floor and inched in close with my 14–24mm lens. Following her carefully, I clicked, on instinct, at the moment when her eyes met mine. It was a connection.

As much as I want to blend in with my surroundings and photograph people unaware of my presence, this 22-minute experience reminds me that my presence does influence the photographs I make, and whether I like it or not, I am seen. The way in which I connect with my subject through my words, actions, expressions, and gestures will influence the photographs I make and the way in which I am able to portray my subject.

“Saturate yourself with your subject and the camera will all but take you by the hand.”

MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE, PHOTOGRAPHER

About the Photographs

![]() It is customary for a young married woman such as Dharma to live with her husband (a marriage arranged by their parents) and his immediate family and to share in the responsibility of caring for her mother-in-law, while Dharma’s husband and brothers-in-law leave the home for extended periods of time to work and earn money for the family. Dharma and her sisters-in-law remain home to farm, prepare food, manage domestic chores, and care for the children.

It is customary for a young married woman such as Dharma to live with her husband (a marriage arranged by their parents) and his immediate family and to share in the responsibility of caring for her mother-in-law, while Dharma’s husband and brothers-in-law leave the home for extended periods of time to work and earn money for the family. Dharma and her sisters-in-law remain home to farm, prepare food, manage domestic chores, and care for the children.

Dharma delivered her first child here in her home, with help from her sister-in-law who used a clean, new razor blade to cut the umbilical cord and helped the new mother to breastfeed her baby within 30 minutes of the birth. What’s significant about this experience is that it’s an innovative approach to in-home delivery and newborn care for this remote region of Nepal. Dharma’s sister-in-law learned about the importance of umbilical cord hygiene and the nutritional benefits of colostrum (early breast milk) for newborns by attending monthly Mothers’ Group meetings in their village. Historically, it has been customary in this region for women to purge the colostrum, as Dharma’s ancestors believed that early breast milk was unclean.

While the Public Health Department of Nepal, with support from CARE, is making great strides to improve maternal health and education in an effort to decrease the infant mortality rate, women in the Doti District rarely have access to health facilities and medical care during labor as transit can be time-consuming and treacherous (particularly during rainy seasons when mudslides are common), and most remote health facilities are not staffed during the night due to lack of resources. Images © Stephanie Calabrese Roberts/CARE.

Connect

Learn more about CARE

www.care.org

Focus on Family, Friends, & the Familiar

It’s not necessary to travel to faraway lands or to seek out unfamiliar subjects to practice documentary photography. In fact, you can find a lifetime of documentary material just by turning your lens on your own life—the people closest to you, in settings that feel most familiar. Finding a level of comfort in documenting people as they are can come more easily if you photograph people who know and trust you and are comfortable in your presence.

When I photograph friends, I often do this while I’m staying in their home for one or more nights, giving us plenty of time to connect and enjoy each other. If I’m shooting an experience for a friend, such as a wedding, I’ll make time to linger between significant moments to reveal unexpected moments throughout the experience—the bride’s father chewing nervously on his fingernails before the ceremony, a goodnight kiss, or the comical expression on a young boy’s face just before he was love-tackled by an older cousin. This stretch of time often opens up unique opportunities to photograph my subjects doing things that come naturally for them, revealing a glimpse of their authentic selves. The longer I am present with my camera, the less significant I become, putting my subjects more at ease.

Zack anticipates a tackle hug from his cousin Lawson.

When I pick up my camera in a personal setting, I can’t help but distance myself from the experience. I become less involved in the action and dialog, and more in tune with following the visual of the experience. I’m thinking about light, making decisions about what to include in the frame of my viewfinder, and anticipating what might happen next. I can’t remain in this zone throughout our entire time together, as I’d miss the opportunity for a personal connection with my subjects, so I find it critically important to put my camera down and be fully present with my subjects at other times.

Expectant mother Jill offers support to son Wyatt and his pepper grinder in the kitchen.

When photographing family and friends in their homes or private settings, discuss your desire to photograph them authentically throughout your visit to ensure they are comfortable with your focus on them. If you hope to share the photographs in a public way at some point in the future, share your intent and gain their consent. If your subject expresses a desire to see the photographs before you share them publicly (particularly if you are photographing sensitive experiences), honor this request and follow through by sharing your images with your subject(s) in a private online environment or in person, and obtain permission before you share your images in a public way. Give your best digital photographs to your subject(s) or make prints as an expression of thanks if they are interested in having the photographs for their personal use.

Mothers Lauren and Paige kiss their son Jesse goodnight.

Nieces (and bridesmaids) of the bride grow tired of the wedding rehearsal.

Papa helps grandchildren Bov and Mary Elise craft a snowman on the back porch while Mimi shivers in the foreground.

Bucky, father of the bride, waits.

Use a Mobile Phone Camera for Spontaneous Documentary

I capture most of my favorite spontaneous moments of my children, my favorite (and most frequent) subjects, on a near daily basis using my iPhone camera and a variety of photography apps, quite simply because the iPhone is always with me and because it’s so unobtrusive. I can easily shoot, process, and share a quick photograph without detaching myself from the experience. The mobile experience of processing my personal photographs in real time, titling them in intriguing ways, and sharing them with my viewers in Instagram and Twitter on my iPhone has become almost as appealing as the act of shooting. Sharing my personal documentary regularly online has been a way for me to gradually open myself up and experiment with photography as a form of expression—to learn what it feels like to expose who I am, what I see, and how I feel. It’s helped me gain perspective on what it feels like to be the subject of a documentary study—a practice of letting my guard down and getting comfortable with a certain amount of exposure and vulnerability. Consequently, it’s helped me gain a new level of appreciation and sensitivity for my subjects, and keeps me focused in the present moment.

My daughter dons her superhero cape before racing along the edge of the pool with her fellow gymnasts in Panama City Beach, Florida.

My daughter takes a quick glance at the future (in a variety of shapes and sizes) from the confines of a shopping cart.

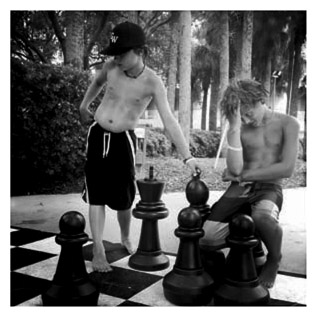

My son plans his next move on the poolside chess set at the Westin Hotel on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, while his cousin questions the result.

My son watches my brother carve the pumpkin to his exacting design specifications.

My son dives off the dock built by his father in the backyard. I shot this image while seated on the pontoon boat beside the dock, known as “ye old barge.”

Raise Questions & Help Seek Solutions

Documentary portraiture carries the weight of making a statement, raising a question, or revealing the truth on behalf of your subject. Shortly after I arrived in Pokhara, Nepal, a friend introduced us to several children known as “street kids” who lived and worked in the hotel downstairs. As I watched the young girls washing dishes with a hose and a bucket outside the restaurant, they seemed content on first glance. Intrigued with my interest and big camera, they giggled and exposed henna designs on the palms of their hands. I was relieved to see them smile because it helped me convince myself that they were okay, but had I only made images of these girls smiling, it would not have revealed the truth of their challenging existence.

My Nepali friend explained that these children had been sent away from their homes to work at the hotel—to earn a place to live, food to eat, and money that would be saved on their behalf when the time came for them to go out on their own. She explained that some street kids are sent to school. Others are not. It moved me very deeply to learn about this way of life, to witness it and document it with my own eyes. As I stood there studying the girls, I wondered what it might feel like to be far from home and to have to accept what’s been given to you without question, to be vulnerable, to have a job at age ten, to appreciate what little you have, and to wish you had been given the chance to wear a school uniform.

Following my brief encounter with these children, my initial instinct was to return home and figure out a way to rally my family and friends to raise money for these children, but my Nepali friend stopped me. It would have been a short-term Western fix to a Nepali problem requiring a more long-term, sustainable solution. The real solution to the problem rests in the inspired hearts and minds of the local change makers in Nepal, individuals like my friend Renu Bagaria, founder of Koseli School. Our resources and support can be channeled to support these local change makers in a way they deem most valuable and in sync with their own culture and environment.

As a documentary photographer, it can be challenging (and perhaps impossible) to reveal harsh truths in life from an objective perspective—to provide answers, support, and/or solutions to your subjects’ challenges. Life is complex. Learn to get comfortable with the questions, and use your talent responsibly as a documentary photographer to broaden perspectives, challenge norms, build empathy, and expose the truth in ways that might create awareness for issues unseen or ignored and generate thoughts that could result in potential solutions. I challenge you (and myself) to find ways to use our talent as photographers and storytellers to not only document, but find a way to benefit the lives of our subjects.