Chapter 2

Observation and Feedback

If data-driven instruction (DDI; Chapter 1) and student culture (Chapter 5) are the “super-levers” of successful schools, observation and feedback is arguably the next most effective. Let's look at the following feedback conversation.

WATCH Clip 3: Julie Jackson demonstrates effective feedback in action, debriefing her observations of Carly Bradley's science lesson.

WATCH Clip 3: Julie Jackson demonstrates effective feedback in action, debriefing her observations of Carly Bradley's science lesson.In just 10 minutes, Julie leads Carly through an incredibly powerful process: a targeted focus on, and practice of, exactly what Carly needs to improve. For Julie, teacher feedback is not about the volume of observations or the length of written feedback; it's about bite-sized action steps that allow a teacher to grow systematically from novice to proficient to master teacher.

Becoming a master teacher is often considered a slow process. Recently, some have argued that it takes as long as 10 years, since the “10-year rule” has been successfully applied to fields other than education.1 Yet for teachers who take part in the sort of observation-feedback loop Julie sets in motion, highly effective teaching comes after just one or two years. The proof? Julie gets outstanding results not only from experienced teachers but from rookies as well. One of the most striking statistics from North Star Elementary School is that the median national score on the TerraNova for kindergarten, first-, second-, and third-grade students, in reading, language, and math, is in the 99th percentile. You don't get these results by placing your best teachers strategically—you get them by coaching each and every teacher to do excellent work.

How is this possible? It takes two steps: spending much more time coaching, and using much more effective coaching tactics. A recent study found that in major metropolitan areas, the median new teacher receives only around two observations a year; the median veteran teacher is only observed once every two years, and, incredibly, nearly one in three veteran teachers were observed only once every three years.2 Julie Jackson's school is radically different: there, every teacher is observed and receives face-to-face feedback every week. That means that each teacher is getting feedback at least 30 times per year—as much as most teachers get in more than 20 years. And Julie's teachers develop accordingly. They might not earn scores of “master teacher” on every teacher evaluation rubric, but they do get master teacher–like results.

When we observe teachers, much of our focus tends to be (rightly) on making every individual observation as meaningful as possible. In the process, though, we often lose sight of any systematic way to track how teachers grow, or to grasp schoolwide trends in teaching practice. For everything we know about teaching from individual visits, there's a lot we can't know, like:

- How frequently is each teacher being visited?

- Who are the teachers you are not seeing often? Why aren't you seeing them?

- What feedback was this teacher given a week ago? A month ago? Last year? How have they put it into practice?

- What are the schoolwide strengths in instruction? What are the areas for growth?

- What feedback has led to meaningful changes for teachers? What feedback has not?

For the leaders we present in this book, the uncertainty surrounding these questions was agonizing. At Julie's school, there now exists a process that answers each of these questions and a system that ensures that the hard work of teacher observation bears results far greater than the sum of its parts. In short, Julie and her colleagues have recognized that observation and feedback are only fully effective when leaders systematically track which teachers have been observed, what feedback they have received, and whether that feedback has improved their practice.

The Traditional Model: Observation Adrift

Sadly, all too many schools still observe less diligently than North Star does—and less frequently. At these schools, observations are stress-packed rituals that occur no more than once a year. Months in advance, each teacher learns when his or her “day of destiny” falls and plans accordingly: shining classrooms to sparkling, honing lessons to perfection, and badgering students to behave well. When the annual 45-minute encounter finally unfolds, the principal observes the year's most dynamic lesson. Unused to the leader's presence, students display stellar conduct. The lesson is successful, and one month later, each teacher receives a carbon-paper checklist with each box marked “Satisfactory.” With a sigh of relief, the whole ceremony ends. Teachers are “safe” for another 11 months. Yet despite all the anticipation, school leaders haven't learned much—nor have they done much to nurture meaningful improvement.

Over the past 20 years, some school leaders have tried to improve this model by using more detailed feedback, more engaged observations, or detailed teacher rubrics that judge instruction. The most prominent such teacher rubric, proposed by Charlotte Danielson in 1996, calls for assessing teaching through a comprehensive framework of elements. Danielson lists 76 elements of teaching that leaders must evaluate, elements that are said to “honor the complexity of teaching … [and] constitute a language for professional conversation [and] provide a structure for self-assessment and reflection on professional practice.”3 Yet while the notion of a comprehensive rubric for teacher assessment is certainly an improvement over the traditional one-observation-per-year model, it still does not address the most fundamental issue. Both normed rubrics and more traditional observations share a fatal flaw: at their essence, they are judgments of teacher quality. Whatever the merits (or accuracy) of these judgments, they neglect a much more relevant question: How can teachers be coached to improve student learning?

This gets at the heart of what most teacher observations miss. Effective observation and feedback isn't about evaluation—it's about coaching.

Recognizing this, school leaders like Julie Jackson have re-envisioned the observation-feedback model, emulating the best practices of other high-achieving principals and of successful leaders from other fields. To meet her primary goal—coaching teachers in ways that drive student learning—Julie has embraced a core commitment:

- Weekly 15-minute observations of each teacher, combined with …

- Weekly 15-minute feedback meetings for every teacher in the building

Take a moment to remember how great a difference this commitment makes: it increases the speed of teacher development exponentially!

At each feedback meeting, Julie offers direct, readily applicable feedback. The next week, she checks that her feedback has been put in place and looks for further areas for improvement, building a veritable cycle of improvement. The result is a set of observations meant not to evaluate but to coach—a change that makes all the difference.

The sum total of these changes is a complete shift in the staff culture of the school. Yet the shift is not to a nerve-wracking, “gotcha” environment. Instead, provided that the main goal of the observations is for teachers to improve practice, the result is greater staff investment, with teachers realizing that their development matters. As Carly herself notes, “The conversations may seem intimidating at first, but in fact it shows just how careful Julie Jackson is as a leader, and how important my own development is to our school.” Paradoxically, the fact that the observations occur at varying times and on a weekly basis makes them less, not more, stress intensive. “Because Julie comes by so often, I never worry that one bad lesson will give a false impression of what class is really like,” Carly explains. Carly is not alone: as Marzano, Frontier, and Livingston note in Effective Supervision, frequent observation leads to less, not more, apprehension, taking a lot of the stress out of the observation process.4

Like the other leaders we studied, Julie Jackson uses a powerful model of observation and feedback:

In the pages that follow, we will see how she creates each of these core components—and the pitfalls she avoids along the way.

Keys to Observation and Feedback

Schedule Observation and Feedback

If the goal of leaders is to coach teachers, it is foolish to observe only one or two times a year. Imagine if a tennis coach said that he would only watch players once every six months, but that he would fill out a detailed report after each visit. If this seems ridiculous, remember that teaching is no different. Teachers, like tennis players, need consistent, regular feedback and practice to improve their craft. At North Star Elementary School, teacher improvement is the name of the game. As one teacher noted, “Julie is all about driving us to the next level, and every week she makes us a bit better.”

Although frequent observation has many benefits, it comes at a cost: time. On first reading, Julie Jackson's extraordinary commitment to observation may seem unsustainable. Where, in the midst of a busy schedule, is the time for weekly visits? In part, Julie is able to observe her teachers weekly because of the systems she has put in place:

- Shorter visits. In contrast to the traditional, hour-long block, Julie observes only for roughly 15 minutes per teacher. As long as leaders are strategic about what they are looking for, this shorter length of time is sufficient for thorough and direct feedback. Indeed, significantly longer observations are often inefficient, especially when they come at the expense of observing far fewer teachers.

- Observation blocks. Grouping observations in hour-long blocks reduces inefficiencies in traveling between rooms and transitioning between tasks. Scheduling three or four brief observations back to back is a good way to gain extra time. On Wednesdays, for example, Julie saves a great deal of time by watching six teachers back to back in a two-hour block.

- Locked-in feedback meetings. Each of Julie's observations is accompanied by a face-to-face feedback meeting. To keep herself on track, she makes a point of scheduling these meetings from the beginning of the school year. Teachers know when they'll meet, which brings stability, and there is no wasted time in email exchanges or tracking down teachers to deliver the feedback. “Even during my busiest weeks,” Julie remarks, “having the meeting on my calendar means I keep making observation a priority.” Locking in feedback meetings also helps leaders stay accountable and committed to the observations they need. Julie affirms, “If I know I have to give that teacher feedback on Thursday morning, I have an extra incentive to get that observation done—I don't want to walk into the meeting empty-handed!”

- Feedback meeting combined with other meetings. Rather than only meet to discuss feedback, Julie combines observation feedback with her other agenda items for her teachers. Almost every week, that includes a discussion on the next week's plans (discussed at length in Chapter 3); four times a year, the whole meeting converts to a data analysis meeting (discussed in Chapter 1). Even if your school does not engage in weekly planning, because feedback and planning are so directly connected, scheduling both in one block is a powerful synergy, making both much more effective. Here is the breakdown:

- 10 minutes: Observation feedback (this chapter)

- 20 minutes: Planning (Chapter 3)

- Distributed observation load among all leaders. Of course, most schools—like Julie's—have considerably more than 20 teachers, and it is impossible for one leader to observe all of them every week. Recognizing this, as North Star Elementary grew, Julie empowered other instructional leaders to conduct observations and give feedback. This is consistent with a poll I made of principal coaches in eight urban districts: Chicago, New York City, Charlotte, Memphis, Baltimore, Oakland, Washington, D.C., and Newark, New Jersey. In these districts, the ratio of total teachers to total school leaders (including vice principals, nonteaching personnel, coaches, lead teachers, special education coordinators, and so on) was never greater than 12:1. We are often reluctant to count every leader (“but they're a floating coach” or “but they don't currently do instructional leadership”), but the reality is that we have the capability to create a 15:1 ratio of teacher to leader in almost every public school.5 (Chapter 7, on school leadership teams, discusses this process in much greater detail; for now, it is important to note here that almost every school has enough potential observers to make this approach work.)

Making It Happen

Your first reaction might be to think this is not all possible in a school leader's day. Let's show how by doing the math:

- Typical teacher-to-leader load (when all leaders are counted): 15 teachers per leader

- One classroom observation per week: 15 minutes

- Total minutes of observation per week: 15 teachers × 15 minutes = 225 minutes = less than 4 hours

- One feedback and planning meeting: 30 minutes

- Total minutes of feedback and planning meetings: 15 teachers × 30 minutes = 7.5 hours

- Total hours devoted to teacher observation and feedback: 4 hours of observation + 7.5 hours of feedback and planning meetings = 11.5 hours

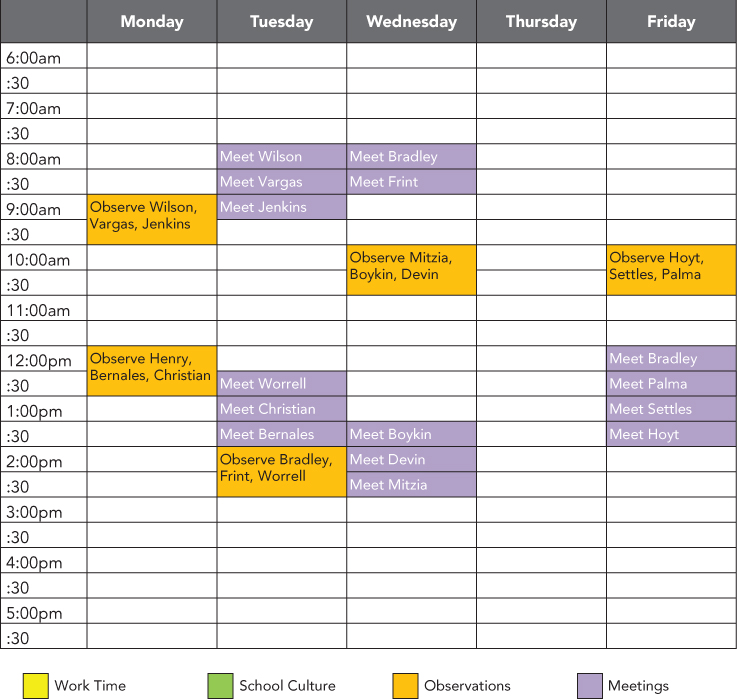

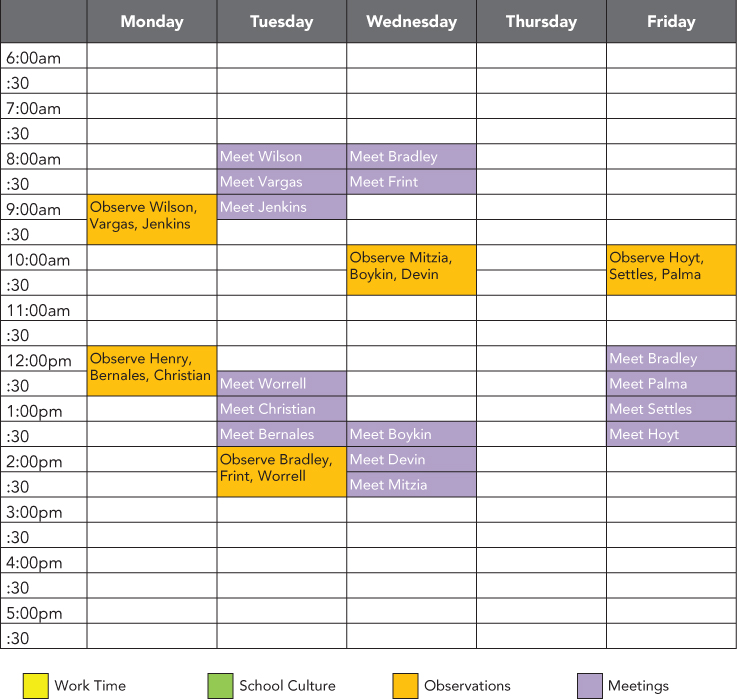

Percentage of a leader's time (assuming a 7:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. school day): 25 percent. Table 2.1 shows how that looks in Julie's schedule.

Table 2.1 Sample Calendar with Observations and Meetings

As you can see, committing to observation and feedback does require a significant time investment—but not an unreasonable one. You can schedule observation blocks and feedback and planning meetings and still have plenty of time for everything else. (See Chapter 8, Finding the Time, for more strategies to keep non-instructional items from interfering with your ability to observe teachers.)

- A laptop for recording observation (or pen and notepad)

- Access to the teacher's lesson plans for the day (Julie has teachers post these in their classrooms; other leaders highlighted in the book receive them via email or hard copy or have them in a shared server where they can find them)

Once you have developed a schedule like this one, you are one step closer to making dramatic improvements to teacher development. The next step is the knowhow to observe effectively.

Identify Key Action Steps

Criteria for the Right Action Step

After 15 years of teaching and school leadership, Julie Jackson doesn't miss much. When she enters Carly's classroom, she immediately sees dozens of areas for comment, from student engagement to the quality of questioning to lesson materials. Recognizing this, some researchers have suggested that ideal observations attempt to capture every significant aspect of teaching at once. In Effective Supervision, for example, it is suggested that observers complete a 41-point rubric for each observation.6 Yet Julie is not looking to find a “laundry list” of faults or make a radical overhaul of Carly's pedagogy. Instead, she limits herself to a narrow, specific action step to increase student learning: “When a student answers incorrectly, ask that same student a scaffolded question to give her a chance to get it right.” She limits herself to just this one key change. Why? Because that method conforms to the way adults actually learn.

Think about the times when you have received a long list of feedback in one meeting. There is no way for you to implement all of that feedback at once. So you are stuck with the task of trying to prioritize what to do first, and many of the other pieces of feedback you've received are left unattended. So why does this happen so often? Because principals using a traditional observation and feedback model feel—rightly—that they have limited opportunities to share all of the feedback they come up with. With a weekly observation model, however, that framework completely changes. Julie Jackson uses weekly observation to take the guesswork away from her teachers. Instead of leaving each teacher to wonder what to prioritize, she answers that question during feedback meetings by limiting her feedback to what is most important.

Focusing on one key piece of feedback also makes more sense given the length of Julie's observations. There is simply no way to assess 40+ points of a teacher rubric in 15 minutes. You would spend more time reading the rubric than observing the class! As Kim Marshall, author of Rethinking Teacher Supervision and Evaluation, notes, “Shorter visits are fine … if they are effective.” So how does Julie Jackson make sure she's focused on the right thing?

There are a number of core criteria Julie uses to separate the high-impact changes from the low-impact and to ensure that the key action steps she chooses are the right ones:

Is the action step directly connected to student learning?

As noted at the start of the chapter, observation works best when it draws on the resources of data-driven instruction. For example, Carly's interim assessment data revealed that her students struggled with “high-rigor” questions, that is, those questions in which students are engaged in more of the cognitive work. From this insight, Julie narrowed her focus to creating higher-level prompting. Of course, many key changes, such as how well disciplined a class is, may not be directly revealed by the data. As a direct record of student learning, however, strong data analysis is a great starting point for coaching teachers forward. Even though she may not be hitting every area for improvement, Julie knows from data and experience that this step will make a concrete difference and will make class better.

Does the action step address a root cause affecting student learning?

Julie's next concern in picking an action step is whether it addresses a root cause of problems in the class or merely a symptom of them. For example, in observing a noisy classroom, it may be tempting to focus feedback on stopping students from acting out of place. But as Julie notes, “Often, classroom management or discipline problems aren't really about how teachers deal with misbehavior; they're about the design of classroom procedures. If the teacher simply worked on building the expectation that all hands stay on student laps, it's easier to prevent students from pushing each other.” Distinguishing a root cause from a superficial symptom takes practice, but there are a few areas where confusion is particularly likely. Consider these examples:

- Common surface problem: Students off-task during group work.

Often the root problems: Lack of explicit roles and instructions for the group work; lack of guidelines for what to do when students get stuck.

- Common surface problem: Students appear bored by content that is not engaging.

Often the root problem: Teacher hasn't created the illusion of speed with effective in-class transitions, all-class responses, and other pacing techniques identified by Doug Lemov in Teach Like a Champion.7

Is the action step high-leverage?

The final criterion is whether the action step notably improves many facets of instruction or is a necessary step for other improvements. Given leaders' limited time and the difficulty teachers face when they try to make many changes simultaneously, it's important to identify the action steps that have the most leverage—that drive improvement for the greatest number of aspects of the lesson at once.

Julie Jackson's Highest-Leverage Action Steps

On some level, identifying the most effective feedback possible is a matter of experience; with practice, it becomes far easier. Yet some shortcuts exist. A good way to start is by studying the best literature around classroom instruction. Teach Like a Champion and The Skillful Teacher were the most-mentioned resources by the leaders in this book.8

Even more valuable is learning from these top-tier leaders themselves. Although there are many facets of classroom instruction that can affect multiple areas, leaders like Julie Jackson think about two critical areas for feedback: management and engagement, and intellectual engagement. While every teacher has different experiences of what works to drive improvements, Julie has identified the areas outlined in “Julie's Top 10 Areas for Action Steps” as the highest-leverage based on her experience. If you want to make effective, immediate impact in teacher instruction, these areas are a good place to start.9

This list isn't complete, and it isn't intended to be. Every teacher needs the action steps that will most affect their instruction. However, by looking for these areas and practicing giving feedback in them, you can greatly develop your eye for teacher development.

Making It Bite-Sized

In The Talent Code, author Daniel Coyle tells a remarkable story about Coach John Wooden, who led the UCLA basketball team to an unprecedented 10 national championships in the 1960s and 1970s. When he studied Wooden's practices, he noticed few pep talks, and no conversation that wasn't accompanied with immediate practice of the skill. Moreover, Wooden wouldn't focus on mastering every aspect of basketball: he would work with each athlete to practice one small part at a time. As Coyle notes, quoting Wooden: “Don't look for the big, quick improvement. See the small improvement one day at a time. That's the only way it happens. And when it happens, it lasts.”10

Most Frequently Used Action Steps by Top-Tier Instructional Leaders

Engagement and Management

- Write out every routine and procedure down to the smallest detail of what is said and done.

- Rehearse these routines with a colleague in the classroom before the students are there.

- Introduce each procedure with short sequential steps.

- Practice routine to perfection: have students do it again if it is not done correctly.

- “I like how Javon has gotten straight to work on his writing assignment.”

- “The second row is ready to go: their pencils are in the well and their eyes are on me.”

- Narrate the positive while looking at the student(s) who are not complying.

- “The last class was able to transition to small groups in 45 seconds. I bet you can do even better.”

- “Now I know you're only fourth graders, but I have a fifth-grade problem that I bet you could master. Get ready to prove how smart you are!”

- Deliberately scan the room for compliance: choose three or four “hot spots” (places where students often get off task) to continually scan.

- Circulate with purpose by moving to different locations on the perimeter of the room.

- Give an instruction, narrate the positive, then redirect student who is not complying.

- Redirect from least to most invasive:

- Use proximity.

- Use a nonverbal.

- Maintain eye contact.

- Say student's name quickly.

- Give a small consequence.

- Anticipate student off-task behavior and pre-rehearse the next two things you will do when that behavior occurs.

- Square up and stand still. When giving instructions, stop moving and strike a formal pose.

- Use economy of language. Give crisp instructions with as few words as possible.

- Do not engage. Keep repeating your core instruction and ignore student complaints.

- Employ quiet power. Lower your voice and change your tone to communicate urgency.

- Do not talk over. Use a reset (for example, all-school clap) to get students' full attention before continuing to speak.

- Use a timer for each aspect of your lesson and let students see how much time they have left during each activity.

- Use brief 15–30-second turn-and-talks.

- Cold-call students.

- Elicit choral responses to certain questions.

Rigor (Intellectual Engagement)

- Data driven

- Curriculum plan driven

- Able to be accomplished in one lesson

- Actively monitor student work, making note of students who have wrong answers.

- Poll the room to see how many students answered a certain question correctly.

- Track right and wrong answers to class questions.

- Implement an exit ticket (brief final mini-assessment) and collect at end of class to see how many students have mastered the concept.

- Script out what you will ask and do when students do not answer correctly.

- Script out the questions and activities that will facilitate students getting to the right answer.

- Push students to use habits of discussion to critique or build off each other's answers.

- Provide wait time after posing challenging questions.

- Build into each class at least 10 minutes of independent practice.

- Support struggling students during independent practice (identify the first two or three students you will support) while continuing to scan the room for compliance (position yourself so that you can still scan the entire room).

- Align independent practice to the rigor of the upcoming interim assessment.

Observing the leaders highlighted in this book, one finds an eerily similar practice. Picking the right area of focus only gets you part of the way there. The next challenge is making sure it is bite-sized: teachers can accomplish it in one week. Julie limits herself to one or two pieces of feedback like this in each meeting, noting that “I try to make sure that every change is a ‘10-second’ change: that you can walk into a classroom at the right time and know, in 10 seconds, whether it has been put into place.” No single small step will dramatically change a classroom in and of itself. Multiple small changes, though, implemented week after week, add up to extraordinary change. The key insight of leaders like Julie Jackson is that feedback and observation make big shifts by focusing on small changes in quick succession. Let's turn back to Clip 3 to see what shape this may take:

REWATCH Clip 3: Julie's feedback and observation meeting with Carly. This time, focus on the specific action steps Julie gives Carly.

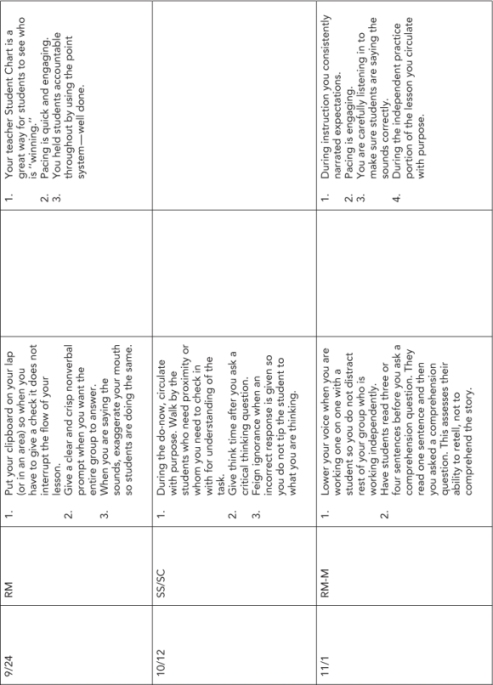

REWATCH Clip 3: Julie's feedback and observation meeting with Carly. This time, focus on the specific action steps Julie gives Carly.To illustrate, page 76 shows the actual bite-sized action steps Julie used week after week with a new teacher who was struggling to increase student engagement and on-task behavior. While such feedback may seem simple or low level, it is precisely these sorts of changes that allow real change to be possible.

Can you imagine how quickly this teacher can develop with this sort of feedback? Incredibly, despite a challenging start, she went on to have all of her students perform in the 99th percentile on the TerraNova. Without this sort of feedback, classroom engagement would have interfered with learning.

A Sample of Julie Jackson's Feedback

- Reduce teacher talk in the introduction by using cold calling and turn-and-talk.

- Get closer to the students in order to keep them on task.

- When you are engaging with one student, deliberately scan the room to make sure all other students are on task.

- During the turn-and-talk, listen in briefly on two or three pairs of students so you can select a pair who had a good discussion and an answer that you want to be heard by the whole group.

- Do not engage. Just give the consequence with your “teacher look” and refrain from getting into the details of why (because it interrupts the flow of your lesson). You can go into the why once the rest of the group is working.

- When you or a student is talking, reinforce other students listening by signaling nonverbally for students to put their hands down.

- Vary the students you are calling on during homework review.

- Pose a critical thinking turn-and-talk and then quickly check in with any students who are confused.

- Check for understanding prior to students doing the “You-Do” portion of the lesson by calling on a student to explain the task.

- Set a timer during independent practice so you have time to close the lesson and check for mastery of the objectives of the lesson.

- After giving directions, allow a quick pause to wait for compliance. Avoid using more language.

- When doing it again, use nonverbals.

Converting Poor Action Steps into Effective Ones

- Poor action step: Reduce student talking when you're speaking.

- Better action step: Don't talk over the students. Stop and make eye contact with the student who is talking. Throughout the lesson walk with purpose toward students who may have a hard time staying on task.

- Poor action step: Be careful about your pacing so as not to sacrifice independent practice.

- Better action step: Set a timer to go off with 20 minutes left in the lesson to remind you when you need to begin independent practice.

- Poor action step: Don't let students jump into the conversation.

- Better action step: Give think time and use cold calls to call on students who haven't yet raised their hands. For the eager student, have her write her response on a whiteboard.

- Poor action step: Keep students calm when entering the classroom.

- Better action step: Have students reenter the room and set the mood for learning and reinforce good behaviors.

Ultimately, finding the right action step takes time. Here we include a practice exercise to consider what the strongest action step should be. Use this exercise as a guide to determine your readiness and sharpen your skills as you move toward finding and articulating key action steps in your own school.

Naming the key action step is a critical step to improving teacher practice. When action steps are fuzzy, teachers must figure them out on their own. That doesn't allow you to be 100 percent successful with 100 percent of your teachers.

- Measurable, observable. You can see whether this has been accomplished when observing and reviewing lesson plans.

- Bite-sized. Teacher can accomplish in the next week.

- Data and goal driven. They are connected to larger professional development (PD) goal and/or DDI goals for the teacher.

Effective Feedback

Naming the key action step is critical to improving teacher practice. However, for Julie's insight to be effective, it must be delivered effectively. To do so, first she avoids some common myths of feedback. You'll find these myths, or “errors,” outlined in “The Five Errors to Avoid.”

Six Steps to Effective Feedback

Julie successfully avoided all of those errors by following six key steps. Together, these six steps form the backbone of an effective school leader's feedback process. Of course, seeing is believing. In going through the feedback steps, this book breaks down each one with video clips and accompanying descriptions.

Step 1: Precise Praise

In the opening video clip, Julie Jackson began her meeting by complimenting Carly on her energy level and enthusiasm. This was not accidental. This was the precise area of feedback from the last meeting, and Julie intentionally observed for this in the previous classroom visit. By linking praise to the previous core action step, Julie triples its impact. Not only is the praise genuine and affirming, but it also gives the teacher the fundamental satisfaction that comes from achieving in a goal that she has worked hard on. Even more, it lets the teacher know that Julie is observing her to see if she implements feedback—it is built-in accountability in the form of praise! Of course, when teachers are not making progress in these core areas, leaders may focus their praise elsewhere. Yet the best praise focuses on the key areas of progress teachers have identified.

Julie Jackson's fellow principal Serena Savarirayan gives another example of effective praise in Clip 4.

WATCH Clip 4: Specific praise helps principal Serena Savarirayan set the tone for her observation meeting with Eric Diamon.

WATCH Clip 4: Specific praise helps principal Serena Savarirayan set the tone for her observation meeting with Eric Diamon.Step 2: Probe

As Beth and Steve's example in Chapter 1 showed, people are much more likely to embrace conclusions they've reached than directives they've received. Recognizing this, Julie leads her feedback discussion with a targeted open-ended question, guiding Carly to come to the solution on her own. While there is no one way to craft a generalized set of probing questions—each question will depend on the action step you are focusing on—Julie follows a few core guidelines in the questions she asks:

- Narrow the focus. The first step is to focus in on one aspect of the lesson. Avoid general questions like “How did your lesson go today?” and prioritize the area where you will generate the action step: questions, transitions, pacing, and so on.

- Begin with the purpose. Ask teachers to articulate the essential reason why they are employing a given practice that is your area of focus. For example:

- “Why do we use student prompting?”

- “What is the purpose of independent practice?”

Step 3: Identify the Problem and the Concrete Action Step

Once the probing question has been asked, the goal is to get the teacher to articulate the problem and concrete action step on her own. What makes Julie Jackson's leadership so skillful here—and it mirrors the techniques of Beth Verrilli in data analysis meetings from Chapter 1—is her ability to guide any sort of teacher toward the action step. The teacher's ability to be reflective and metacognitive will determine what level of scaffolding she needs to provide. Here are the four levels of support that Julie provides based on the responsiveness of the teacher:

Let's look at how each of these levels plays out with real teachers.

Level 1: Teacher Identifies the Problem

Some teachers are capable of identifying the core issues in their lessons. In that case, Julie's role is simply to guide them to articulating a specific action step. For example, in Clip 5, she can be seen working with Rachel Kashner around a science lesson on understanding the parts of the backbone. Rachel immediately identifies that the weak spot in her lesson was a lack of an assessment of all students' learning. “I didn't have an assessment to check the understanding of all the students.” With that opening, Julie simply asks Rachel questions about why this was an issue and how she could address it in the future. At the last prompt, Rachel notes, “Next time, I will add a written component before the class discussion so I can monitor how all students understood the concept.” See what it looked like in Clip 5.

WATCH Clip 5: Julie Jackson supports experienced teacher Rachel Kashner in finding areas for growth and solutions for improvement.

WATCH Clip 5: Julie Jackson supports experienced teacher Rachel Kashner in finding areas for growth and solutions for improvement.Even in the case of such a reflective teacher, Julie's role is still actively present in asking questions that narrow the focus on a specific action step and ensure that a teacher understands the rationale for that action step. Julie simply asks the right questions, and the teacher can do the rest of the thinking on her own.

Level 2: Leader Asks Scaffolded Questions

When a teacher cannot identify the problem from the first probing question, Julie Jackson asks additional scaffolded questions that help the teacher get there. These prompts usually involve recalling what happened in class. Examples include:

- “What did you say when you went to prompt Simon?”

- “How much time did you leave for independent practice?”

- “Do you remember what happened with Jessica during opening procedures today?”

What makes these questions so effective is that if the teacher is able to remember what happened during the lesson at this point, he or she often realizes the issue on the spot. These questions allow a teacher to see his instruction with fresh eyes, guiding his focus to something he didn't realize was so important in the midst of teaching. For many teachers, this process feels like switching the lights on to their instruction.

In other cases, the teacher needs more than just questions. Let's revisit the opening vignette of this chapter. In this case, Julie followed up her opening question with a piece of evidence from the classroom observation: “What happened with Simon when you called on him to answer a question about mammals?” After Carly answers the question, Julie asks her, “What does that do to the level of questioning?” Then Carly is able to figure out what happened.

Watch as Serena Savarirayan and Aja Settles use this same technique.

WATCH Clip 6: Serena Savarirayan guides Eric Diamon toward strategies that deepen class discussions.

WATCH Clip 6: Serena Savarirayan guides Eric Diamon toward strategies that deepen class discussions.

Level 3: Leader Presents Classroom Data

Sometimes scaffolded questions targeting a moment in the lesson are not enough. A teacher might not be able to recall what happened or have a blind spot. For these reasons, it is vital for the leader to be prepared with specific, fact-based observations about what happened at what time. Consider the following exchange:

- Ask scaffolded question. “Do you know how long it took students to enter the classroom?”

[Teacher does not have an accurate answer.]

- Present the data. “I timed students, and it took them four minutes from the time they entered the room to the point where every student was working.”

[Teacher is surprised by the answer.]

- Ask why this is important. “What does that do to the student learning?”

[Teacher notes the lost time for learning; leader can add detail if teacher answer is insufficient.]

- State the action step. “This is what we're going to focus on today: reducing classroom entry to two minutes to save instructional time and also start in a more productive fashion.”

By following this sort of exchange, leaders help teachers to realize the discrepancy between their self-awareness and the reality of the lesson, thus increasing their metacognition and building their capacity to self-correct. By doing so, the leader helps the path toward finding a solution for any problem become clearer.

Another effective tool for getting teachers to identify the problem is to watch a video of best practices from a master teacher and compare it to their own teaching. Watch as Aja Settles uses this approach.

WATCH Clip 8: Aja Settles uses video footage of a master instructor to help Kristi Costanzo hone her teaching practice.

WATCH Clip 8: Aja Settles uses video footage of a master instructor to help Kristi Costanzo hone her teaching practice.Of course, if feasible, leaders can also have teachers record their own practice and use the video as a jumping off point. As Mike Mann, principal of North Star High School, has noted, “Teachers, especially early career teachers, can get so caught up in delivering their lessons that they miss the big picture. Videotaping their classes is a great way to bring in perspective and guide teachers toward improvement.” Watch Clip 9 to see how Juliana Worrell, school leader at North Star's Fairmount Elementary School, uses this footage to help a teacher reach the right action steps.

WATCH Clip 9: Juliana Worrell and Clare Perry use videos of Clare's classroom to find action steps for improvement.

WATCH Clip 9: Juliana Worrell and Clare Perry use videos of Clare's classroom to find action steps for improvement.Level 4: Leader States the Problem Directly

In a few cases, despite all the scaffolding and presentation of the classroom observation data, a teacher still won't be willing or able to recognize the challenge. In these rare moments, the principal simply needs to state the problem and the clear, precise action step. This strategy should only be used if a teacher fails at the other levels or has consistently struggled to improve his or her practice.

In general, leaders err too much in reverting to this level simply because of its convenience. Remember: Even if you are observing weekly, you are still only observing 1 percent of instruction. As such, it is critical for teachers to develop the craft of self-analysis and self-correction.

Summary of the Four Levels

What Julie is doing here is following a strategy: she provides only the scaffolding that the teacher needs to get to the answer. The order of strategies is as follows:

Why is this model so effective? By leading this way, Julie pushes the onus of the thinking onto the teacher. This practice develops reflective teachers who are capable of critiquing themselves when they're not being observed. As Julie notes, “As teachers get in the habit of looking for the root cause, my job gets much easier.” Little by little, a novice teacher starts to identify more of his or her own errors and make on-the-fly adjustments. What Julie has done is turn on the light bulb for more effective self-analysis of one's teaching.

Step 4: Practice

John Wooden famously said, “The importance of repetition until automaticity cannot be overstated. Repetition is the key to learning.”12 Too many interactions between leaders and teachers end in a description of what will happen but no actual practice. That puts the burden of implementation on the teacher alone. But for Julie Jackson, in-the-moment practice represents an essential commitment to good coaching. “Basketball coaches don't lead by conversations; they have players practice their dribbling,” Julie explains. “It's in the repeated and careful practice that teachers learn the skills they need and really get it down.” That sounds very much like Mr. Wooden!

This reflects a crucial insight: for feedback to truly be effective, leaders must allow teachers to practice “on the spot,” whether through role plays or by scripting changes into their lessons (depending on the action step). Great teaching is not learned through discussion; it's learned by doing.

While it flies in the face of conventional school customs, in-the-moment practice separates the top-tier leaders from the rest. Consider what happens in Julie's meeting with Carly when Julie begins with the question, “If we want to think about next steps, what might you do in order to make sure that your prompts split complex questions into smaller parts to guide students?” At that point, Julie has Carly practice asking the questions to her as if she were a student. Juliana Worrell takes the same approach in her work with Julia, as shown in Clip 10.

WATCH Clip 10 to see Juliana Worrell coach Julia Thompson in the immediate role-play practice of her decoding lesson. Role playing allows Juliana and Julia to practice teaching techniques.

WATCH Clip 10 to see Juliana Worrell coach Julia Thompson in the immediate role-play practice of her decoding lesson. Role playing allows Juliana and Julia to practice teaching techniques.Practice is not just for novice teachers; it can also allow you to be a thought partner with your strongest teachers as together you plan out implementation. Watch Serena Savarirayan take the role of the teacher as she works with Eric to develop effective questions for the classroom conversation in Clip 11.

WATCH Clip 11: Serena Savarirayan and Eric Diamon practice questioning approaches.

WATCH Clip 11: Serena Savarirayan and Eric Diamon practice questioning approaches.The speed of teacher development rises dramatically. This high rate of development is one of the distinguishing characteristics of top-tier leaders, and these clips show you why.

Step 5: Plan Ahead

Now that Julie and her teachers have identified an action step and practiced it, they can write it into future lesson plans to lock it in place. In some cases, the nature of an action step will make designing lesson plan components or activities unnecessary. If, for example, the action step is related to addressing student noncompliance when it arises, it won't fit neatly into a lesson plan. Even then, though, the precise words a teacher will use can be written down, possibly on a note card he or she will attach to a clipboard. You can see how Juliana Worrell leads her teacher through that very exercise in Clip 12.

WATCH Clip 12: Juliana Worrell and Sarah Sexton plan think-alouds for an upcoming lesson; when Sarah struggles, Juliana supports her through active modeling.

WATCH Clip 12: Juliana Worrell and Sarah Sexton plan think-alouds for an upcoming lesson; when Sarah struggles, Juliana supports her through active modeling.In the next chapter (Planning), we go into more depth on how leaders shape effective lesson plans to prevent problems from happening.

Step 6: Set a Timeline

Julie leaves nothing to chance: in every feedback session, she has a concrete timeline for implementation. Because action steps are already designed to be accomplished in a week, Julie finds it easy to monitor these timelines. She still records each implementation component when needed: when a teacher will turn in lesson plans, when she will change the classroom setup, and other phenomena.

Writing a timeline might seem like an obvious step, but I cannot emphasize enough how many leaders I observe who skip it. They assume that teachers will implement action steps without a timeline to use as a guide. This will be true for the large majority of your teachers, but if you're striving for excellence for 100 percent of your teachers—and that is the only way to get exceptional results—you need to set a timeline. Timelines are basic, but they help all of us stay on target to what we're trying to accomplish! See how Julie ends her meeting with Rachel Kashner with a timeline in Clip 13.

WATCH Clip 13: A set timeline keeps Julie Jackson and Rachel Kashner on the same page.

WATCH Clip 13: A set timeline keeps Julie Jackson and Rachel Kashner on the same page.Shradha M. Patel sets an even more basic timeline that is just as effective in Clip 14.

WATCH Clip 14: Shradha M. Patel closes her feedback meeting with Jamil Sylvester by establishing a timeline for action.

WATCH Clip 14: Shradha M. Patel closes her feedback meeting with Jamil Sylvester by establishing a timeline for action.For the vast majority of teachers, the observation-feedback system outlined in this chapter will have a tremendous impact. By putting action steps into place, teachers will witness phenomenal improvement in their own practice and, most important, in student learning. Moreover, greater accountability will also reveal the exceptions to this rule: the teachers who are struggling to improve and who are not putting actions into practice effectively. What happens when you discover teachers like these?

When Feedback Isn’t Working: Strategies for Struggling Teachers

Julie Jackson knows this well. Although most teachers at her school improve tremendously in their first months, there are occasionally teachers who struggle. Three years ago, Erin Renz began teaching at Julie's school. Erin was hard working, determined, and enthusiastic, but she was struggling tremendously and student learning was suffering. As she wrote in her reflection from that time period:

I felt like there were hundreds of things I needed to change, and I pulled randomly from the bank of examples I had been sponging up and tried to balance this unsuccessfully with a growing task list.

Erin seemed to be on the road to failure. Even Julie noted, “By the end of October, I didn't know if she would make it through to the end of the year.”

Yet despite this concern, Julie—and her team—rallied to help Erin. Let's look at Erin's own reflection on that process:

I was convinced I lacked some sort of fundamental connector allowing me to effectively implement something I saw modeled. It was then that Julie said, “You are already working hard. We need to teach you to work smart.” This became my new mantra. I found that the key was not in implementing what I saw—it was in understanding what was important, or most important about what I saw. Julie would point out the important things to notice—the really strong elements of taxonomy, or the nuances of classroom management I was missing. Afterward, in our frequent meetings, we would compare notes. I wasn't just learning how to teach, I was developing an eye for good teaching. We set up a system of identifying the goals I was to implement that day, the next day, and the next week.

Over the course of eight months, Erin slowly began to see her teaching transformed. She made bite-sized change after bite-sized change: speaking more economically when giving directions, rearranging desks to more easily transition to and from group work, creating clearer posters to reinforce instruction, providing more time for students to think about questions, and a host of others. With each change, she got a bit better. The results, by year's end, were dramatic: Erin's students matched the performance of her colleagues in scoring well above the 90th percentile. She had made it through the year, and her students had learned. Her final reflection of the year:

From where I stand now, it is almost impossible to believe that only eight months ago I felt completely unsuccessful. I am writing this as I sit at my desk during curriculum planning week, working with the team to develop curriculum. I feel like I am making a meaningful contribution. This year will still be an uphill race, but I feel strong and confident and ready.

Erin's story is inspirational, and it continues to bear fruit. Erin currently is a manager of teacher leadership development for Teach For America, sharing her experience and coaching a cohort of teachers to follow in her footsteps.

Erin's success—and that of many teachers like her—is a product of far more than Julie's unwavering commitment to her staff. Desire and dedication alone do not make a leader effective. This level of success with a struggling teacher also reflects a number of crucial systems and approaches that can be put in place for any teacher who needs them.

Early Warnings: Yellow Flag Strategies

If several feedback cycles have elapsed and teachers have failed to improve, leaders should consider the following strategies. We've labeled these techniques “yellow flag” strategies. A yellow flag at a beach is raised when danger is mounting. Similarly, the strategies listed here should be employed when teachers are continuing to struggle, and the standard observation and feedback cycle needs additional structure.

- Provide simpler instructions and techniques. Sometimes, the bite-sized action steps need to get even smaller. One of my personal favorites from watching Julie Jackson in action was with a teacher who lacked enthusiasm. What became apparent was that the teacher was not a morning person and generally got better later in the day. So Julie's feedback addressed that directly: “Drink some coffee before work, stand up straight, and talk louder!”

- Give face-to-face feedback more often. If the usual observation and feedback cycle is not making change, leaders can extend it through more informal face-to-face contact.

- Plan immediate post-feedback observation. Rather than waiting a week to see if feedback is being implemented correctly, drop by the struggling teacher's classroom the next day. Shortening the feedback-observation loop ensures that if action steps are not working out, leaders know this as soon as possible.

- Arrange for peer observation. Strong leaders recognize that struggling teachers often benefit from sitting in on a star teacher's class. A word of caution: Jon Saphier, author of The Skillful Teacher, notes the perils of this action, because the observer can look at the wrong things.13 To mitigate this, leaders like Julie Jackson observe alongside the struggling teacher, pointing out key moments.

- Choose interruptions with care. Occasionally, if teachers are continuing to struggle, strong leaders interrupt their class to model the technique. For example, a principal might interrupt an elementary school teacher during “guided reading” to demonstrate how students should be questioned. This technique sounds far more disruptive than it is in practice. For example, an instructional leader observing a class might say, “Mrs. Smith, an idea occurred to me. Could I ask the class a question?” Students are unlikely to see this as a break in instruction, and the teacher has an opportunity to observe new techniques put to use in her own classroom. Note, however, that leaders should only try this if they have instructional expertise in that classroom area. Otherwise, they risk putting the students further behind than they were before. As important, teachers may feel that their trust has been violated or feel disrespected, and feelings like these may damage relationships. Pick only the interruptions that will produce the biggest gains in learning. If the expected gains from the interruption aren't large, find another way to model the techniques you'd like to try.

Continued Struggles: Red Flag Strategies

If the strategies outlined fail to produce reasonable results, then more intense interventions may be needed. These strategies can be thought of as “red flag” strategies, just as the red flag on a beach signals serious danger. These solutions should be used only when other means have failed and when more drastic options, such as termination or radically reducing the teacher's course load, are being considered.

- Model entire lessons. For a struggling teacher, it can be extraordinarily helpful to see an entire lesson taught by a master teacher and then repeat it himself later that same day. Before the lesson, the model teacher should talk to the struggling teacher and explain exactly what he or she plans to do and what to look for during the class. Of course, this sort of change is time intensive, and as a result, it should only be used when warranted.

- Take over. Takeover is the most extreme form of intervention, but in rare instances it's the best strategy available to you. During a takeover, a master teacher takes over a struggling teacher's class twice a week for six weeks. The struggling teacher observes these classes and works closely with instructional leaders to improve his or her teaching.

Of course, takeover takes a tremendous amount of dedication and resources, and in many cases, you will not have that flexibility. The fundamental reality of Erin's situation—and the situation of teachers like her—is that it takes a tremendous investment of time to bring them back on track.

Accountability: Tools for Keeping Track of It All

The final piece of the puzzle is accountability: ensuring that feedback becomes practice. The number one challenge is keeping track of it all! Julie and the other leaders highlighted in this book have found a simple, novel solution: an observation tracker. This is a simple tool with which they can record their weekly observations. In the Excel version of the tracker, each tab represents a different teacher. (I'm certain that a specific software application for teachers will not be far behind!) Let's take a look at the tracker for a middle school principal and her observations of a math teacher.

The Observation Tracker

Up to this point, we've considered how Julie makes each individual observation as effective and meaningful as possible. Yet while each of her observations is influential, Julie's impact on instruction is far greater than the sum of her visits. Even the most astute classroom observer faces significant limitations on the information he or she has about teacher development. What are these?

- Patterns across time: What has the teacher been working on for months? What goals have been met already? Without this information, leaders may have no way to evaluate how teachers have developed over time, to assess where they are now against where they once were.

- Patterns across teachers: What challenges are problems for the whole school? Which are limited to just the new teachers? Just the math department? Leaders may have no way to systematically track trends in teaching practice across their school or to quickly recognize areas for improvement that cross different classrooms.

- Patterns of visits: Who are the teachers you are avoiding observing? Whom do you always see? Leaders often do not know which teachers have been visited and how often these visits have happened.

- Patterns of effectiveness: What feedback is solving the problem? What's falling flat? Most important, leaders often have no way to quickly check whether the feedback they give is effective in changing practice.

Gathering this information can be game changing; if leaders had a way to quickly and intuitively record it, they would be able to drive instructional feedback well beyond any one visit. Through her observation tracker Julie Jackson has found a way. The observation tracker is a tool for keeping track of:

- How often you observe

- Patterns of your feedback

- Teachers you're avoiding

- Precision of your feedback

The tracker is a spreadsheet document containing two sets of information: a tracker for each individual teacher, and a schoolwide tracker for all teachers in the building. Table 2.2 presents a sample observation tracker.

Table 2.2 A Sample Observation Tracker: Individual Tab

As you can see, the individual tracker provides the basic details of each observation: when, what action step, whether that action step was implemented, and a space for general notes. Julie and the rest of the leaders in this book carry their laptops to every observation and record the action step on the spot. That way there is no additional work to maintain the tracker. Then she simply pulls it up during the feedback meeting to remind herself of what she observed.

By contrast, the schoolwide summary sheet of the observation tracker gives you the quick facts about each teacher: how many times you've observed, the date of your last observation, and the PD goals and latest action steps for every teacher. Table 2.3 presents a sample from Julie's schoolwide tracker.

Table 2.3 Julie's Observation Tracker

In one brief glance, Julie can make a quick review of the professional development goals of staff and the latest action steps, making it easy for her to know what she is looking for on her next set of observations. This summary can drive decisions on what PD she should deliver given patterns that might emerge across her teachers. Just as significantly, the tracker tells the real truth on how often Julie is observing, and it is easy for anyone to see that, including her supervisor. (We talk more about this in Chapter 9, The Superintendent's Guide.)

Julie Jackson does not personally coach every teacher in the building—there are too many to do weekly. Instead, just as Beth served as instructional leader for Steve in Chapter 1, Julie has chosen several veteran teachers to serve as instructional leaders at North Star. Each of these leaders also owns an observation tracker, even if he or she is a mentor teacher working with only one teacher. This tracker becomes the essential tool for Julie to support leader effectiveness and make sure every leader is working effectively. (See more about the power of this tool for school leadership teams in Chapter 7.)

Sarah Sexton

Turnaround: What to Do First

A legitimate question to ask is how to implement a new observation and feedback cycle like this one with teachers who have never experienced anything like this before. Won't they resist such a change? I look no further than Kim Marshall, who was a pioneer for shorter observations as principal of the Mather School, an elementary school in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Many years later, he recounted his personal experience about how he started to move to briefer observations in his book Rethinking Supervision and Evaluation. Marshall notes:

At first, teachers had their doubts about the mini-observation idea. I had introduced it at the beginning of the year, but teachers were still uncertain about what to expect. Several were visibly relieved when I gave them positive feedback after their first mini-observation. One primary teacher practically hugged me when I said how impressed I was with her children's Thanksgiving turkey masks. But others were thrown off stride when I came into their rooms, and I had to signal them to continue what they were doing. I hoped that as my visits became more routine, these teachers would relax and be able to ignore my presence. And that's what happened in almost all cases.14

Steve's Story

Based on his experience and that of other leaders, there are two key points to highlight with your staff when launching this model:

- Make it clear that the purpose is coaching and improvement, not evaluation.

- Frame progress positively.

The greatest source of buy-in? The answer is as simple as it was for data-driven instruction: results, results, results. When teachers see their practice gradually improving and that they are getting consistent feedback, it really pushes them forward and gets them much more excited. Of course, a small handful of teachers may still remain recalcitrant. At this point, however, the challenge shifts from apathy to intentional defiance, a question we take up in Chapter 6 on staff culture.

When launched effectively, the real turnaround will not be teacher resistance, but your own resistance: resistance to stepping foot in people's classrooms far more often, getting out of your office, and so on. That's the heart of turnaround, and that is something you can control.

Conclusion: Coaching Teachers Toward Greatness

The more time people spend in education, the more cynical about the observation and feedback process they seem to become. This doesn't have to be the case. Our exposure to the traditional model of observation and feedback can blind us to the possibility of doing the job well, but we must cast our cynicism aside. Leaders like Julie Jackson highlight the axiom that great teachers aren't born—they're made. And there is no better way to drive student learning than to develop the talents of the teachers who spend hours educating them every day.

Six Steps to Effective Feedback: Leading Post-Observation Face-to-Face Meetings

| Leader should bring: | Teacher should bring: | |

| Observation Tracker | Laptop and school calendar | |

| One-Pager: Six Steps for Effective Feedback | Curriculum plan, lesson plans, materials, | |

| Preplanned script (questions, observation evidence, | data or student work | |

| and so on) | ||

| Praise: Narrate the positive | ||

| 1 Praise | What to say:

“We set a goal last week of ____ and I noticed this week how you [met goal] by [state concrete positive actions teacher took].” “What made you successful? How did it feel?” | |

| Probe: Start with a targeted question | ||

| 2 Probe | What to say:

“What is the purpose of ____ [certain area of instruction]?” “What was your objective or goal for ____ [the activity, the lesson]?” | |

| Identify Problem and Action Step: Bite-sized action step (do in a week) and highest lever; add scaffolding as needed | ||

| 3 IdentifyProblemandActionStep | What to say

Level 1 (Teacher-driven): Teacher identifies the problem: “Yes. What, then, would be the best action step to address that problem?” Level 2 (More support): Ask scaffolded questions: “How did your lesson try to meet this goal/objective?” Level 3 (More leader guidance): Present classroom data: “Do you remember what happened in class when ____?” [Teacher then identifies what happened.] “What did that do to the class or to learning?” [Show a video of the moment in class that is the issue.] “What happened in this moment?” [or the appropriate question to accompany the video] Level 4 (Leader-driven; only when other levels fail): State the problem directly: [State what you observed and what action step will be needed to solve the problem.] [If you modeled in class] “When I intervened, what did I do?” [Show video of effective practice] “What do you notice? How is this different than what you do in class?” | |

| Practice: Role-play or simulate how to improve current | ||

| or future lessons | ||

| 4 Practice | What to say:

Level 1: “Let's practice together. Do you want me to be the teacher or the student?” Levels 2–4: “Let's try that.” [Jump into role play.] “Let's replay your lesson and try to apply this.” “I'm your student. I say/do ____. How do you respond?” Level 4: [Model for the teacher, and then have them practice it.] | |

| Plan Ahead: Design or revise upcoming lesson plans to | ||

| implement this action | ||

| 5 Plan Ahead | What to say:

“Where would be a good place to implement this in your upcoming lessons?” “Let's write out the steps into your [lesson plan, worksheet/activity, signage, and so on.]” | |

| Set Timeline forFollow-Up | ||

| 6 SetTimelineforFollow-Up | What to say:

“When would be best to observe your implementation of this?” Levels 3–4: “I'll come in tomorrow and look for this technique.” What to do: Set timeline for: Completed materials: When teacher will complete revised lesson plan/materials Leader observation: When you'll observe the teacher (When valuable) Teacher observes master teacher: When they'll observe master teacher implementing the action step (When valuable) Video: When you'll videotape teacher to debrief in upcoming meeting |

|

Note that the meetings labeled in this schedule (Table 2.4) are for both feedback and planning. If you choose a planning system that completes planning work at the start of the year, these meetings can be half of the length they are shown above. (See Chapter 3 for more on different approaches to planning conferences.)

Table 2.4 Making it Work: Where It Fits in a Leader's Schedule

Action Planning Worksheet for Observation and Feedback

Self-Assessment

- How frequently are your teachers being observed? ____/year or ____/month

- Which of the six steps of effective feedback are being used to give your teachers feedback?

- Which of the six steps would most enhance the quality of your schools or your own feedback?

Planning for Action

- What tools from this book will you use to improve observation and feedback at your school? Check all that you will use (you can find all on the DVD):

- What are your next steps for improving observation and feedback?

| Action | Date |