3Market Entry Strategies

3.1About Strategy and Internationalization

The term strategy goes back to Chandler, who defined strategy ‘as the determination of the basic long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise and the adoption of courses of action and allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals’ (Chandler, 1962: 23). Consequently, strategic management is a set of managerial decisions and actions that determine the long-run performance of a firm. Therefore, strategic management emphasizes monitoring and evaluating of external opportunities and threats in light of an organization’s internal resource strengths and weaknesses. The strategy of a corporation involves a comprehensive master plan stating how the corporation will achieve its mission and objectives and maximize its competitive advantages (Wheelen & Hunger, 2010: 53, 67). The concept of strategic management is focused primarily on the development of long-term corporate success. Strategies, due to external or internal circumstances, sometimes cannot be realized as planned. In this case, the strategy needs to be modified. Emergent and deliberate strategies create the firm’s realized strategy (Mintzberg, Lampel, Quinn, & Ghoshal, 2003: 5). Strategy indicates a complex bundle of planned activities for the attainment of long-term business objectives that also should consider emergent decision and action patterns. Optimal allocation of the firm’s entrepreneurial and management capabilities is of vital importance for effective strategy implementation (Kutschker & Schmid, 2006: 798).

Larger firms, such as multinational enterprises, usually follow three types of strategies that are hierarchically linked to the firm’s corporate level, strategic business unit (SBU) level, and functional (department) level. On the top management level (corporate level), there are directional strategies that can be categorized as growth, stability, and retrenchment strategies. A growth strategy, as the term itself indicates, is launched in order to increase the firm’s turnover and profits through expansion. A stability strategy is implemented after the acquisition of another firm, so organizational integration of the acquired business activities is required. A retrenchment strategy is realized through the shutdown or outsourcing of businesses that continuously accumulate losses, and there is little hope that these poorly performing business units will recover in the future.

In more detail, growth strategies are realized by expanding business activities in the current industry through enlargement of the current product portfolio or manufacturing depth (horizontal, vertical, backward, or forward integration) in related industries (concentric diversification) or in unrelated industries (conglomerate diversification). Porter’s concept of competitive strategies, such as cost leadership, differentiation, and niche strategies, is found in the firm’s strategic business units (SBUs) (Porter, 1999: 32–38; Wheelen & Hunger, 2010: 67).

Strategies on the functional level are embedded in the firm’s operating departments, such as purchasing (e.g., parallel or multiple sourcing strategies), marketing strategies (e.g., penetration versus skimming strategy, push versus pull strategy, shower versus waterfall strategy), R&D (technological leadership versus followership strategy), and operations strategies (e.g., individual versus serial production or mass production). A functional strategy implements and realizes directional and business unit strategies by maximizing the firm’s department strengths and effectiveness. Functional strategies are concerned with developing a distinctive competence in order to provide the enterprise and its business units with a competitive advantage (Wheelen & Hunger, 2010: 68).

In light of globalized integrated valued added activities and trade and capital flow patterns, a firm’s growth strategy is often realized through enlargement of its business by means of geographic expansion into foreign markets. As a result, the firm is engaged in internationalization processes because its products and services are transferred across national boundaries. The firm’s management selects the country and relevant actors; where or with whom the transaction should be performed; and the corresponding international exchange transaction modality, which is called a firm’s market entry strategy or, synonymously, market entry mode (Andersen & Buvik, 2002: 347–348). An entry mode refers to the institutional or organizational arrangement chosen by the firm for its business activities in target foreign markets (Hollensen, Boyd, & Ulrich, 2011: 7). The international business activity can range from manufacturing of goods, to servicing customers, to sourcing various inputs (Holtbrügge & Baron, 2013: 239; Welch, Benito, & Petersen, 2007: 18). When entering new markets, the operating management is confronted with various challenges that usually come along with more or less known societal, ecological, economic, legal-political, expertise (S.E.E.L.E), environmental surroundings of the firm. Thus, there should be various advantages from international business activities that cause firms to consider taking the risk of entering foreign markets. What motivates a firm to internationalize? The following are the main reasons.

- Demand-oriented factors: Foreign market entry because of its attractiveness in terms of market volume and growth rates, which provide additional sales volumes, in addition to (often) saturated home markets.

- Supply-oriented factors: Access to rare and valuable resources found in foreign markets, such as qualified and motivated employees, raw materials, knowledge, technological expertise, infrastructure, and others.

- Follow-the-customer necessity: To avoid the risk of being dropped from the procurement list of an important customer, the supplier needs to follow its customer, which is engaged in a foreign target market.

- Follow-the-competitor necessity: To avoid leaving the competitors either with all the sales opportunities or all the investment benefits provided in a regional industry cluster in foreign markets, the firm must join the competitors in the foreign markets.

- Financial reasons: To realize the advantages of foreign markets because of investment incentives (tax reductions, subsidies), large multinationals can make use of cross-stock listing, less costly debt financing because of lower interest rates, and the higher liquidity of the foreign markets.

As is clear from the reasons presented above, a firm does not always make its decision about whether, where, and how to internalize independently but often makes the decision as a result of its bilateral relationships with other actors in its relevant industry network.

The strategic decision process in the course of entering foreign markets is relatively complex, and the outcomes of foreign business normally have a vital impact on a firm’s destiny. In other words, the decision regarding the foreign entry mode strategy is one of the most critical for the management. Among others, it is usually costly to change the mode of entry once it is established due to its long-term consequences for the firm (Brouthers & Hennart, 2007: 396; Pedersen, Petersen, & Benito, 2002: 340).

The choice of which foreign country to enter commits a firm to operating in a certain geographical and sociocultural terrain and signals its future strategic intention to customers, suppliers, competitors, and other stakeholder (Ellis, 2000: 443). The portfolio of international market entry strategies can basically be distinguished among contractual forms (e.g., exports, franchising, original equipment manufacturing); cooperative partnerships, such as international joint ventures; and foreign direct investments (e.g., wholly owned subsidiaries). These strategies will be explained in detail in the following sections of the chapter.

3.2Case Study: The Global Strategy Concept of Samsung

3.2.1Samsung management philosophy – history and today

The Korean economy is characterized by local-market-dominating Chaebols with highly centralized decision structures that consist of many affiliated companies. Compared to large Japanese conglomerates (Keiretsu), Chaebols are generally much younger. The oldest, Samsung, was established in Taegu in 1938 (Chen, 2004: 144) by Byung-Chull Lee (Samsung, 2007). Unlike Chaebols such as LG Electronics, which was founded in 1947, Samsung’s origin goes back to the period of Japanese occupation of the Korean peninsula.

Confucian heritage is still readily visible in South Korea; and the influence of Confucian values on management is significant, which is particularly the case for the most conservative and powerful conglomerate Samsung. Although Buddhism has generally been accepted as a religion in South Korea and has become an integral part of the lives of Koreans, there is a major difference between Buddhism and Confucianism: Buddhism is understood and practiced as pure religion; and it recognizes heaven, hell, and transmigration. It teaches that anyone can enjoy the life of heaven if he or she lives a virtuous and honest life in this world. Heaven is the reward for what a person has done on earth. In comparison, Confucianism, as originally observed in China, is understood more as a philosophy with moral teachings than as a religion. It is involved in the world, rather than emphasizing the afterlife (Chang & Chang, 1994: 10).

The five cardinal values of Confucianism: filial piety and respect, the submission of wife to husband, strict seniority in social order, mutual trust in human relations, and absolute loyalty to the ruler still permeate the Korean society. Nevertheless, today, particularly among the younger and urban population, traditional Confucian ethics, such as family or the collectively oriented values of the East, have mixed with the pragmatic and economic goal-oriented values of the West. Behavior based on Confucianism has changed for reasons that include the influence of Christianity, which came to Korea in 1884 (today Catholics represent around one third of the population), and, to some extent, because of the US presence since the Korean Civil War. Traditional hierarchical roles have changed. Today, scholars and civil servants are at the top; farmers, second; artisans, third; and merchants, last, which has made it possible for businessmen and engineers to prosper in the new industrial society (compare: Kim, 1997: 68; Tu, 1984).

In Korea, as in most of the other Asian countries, education is greatly emphasized. For this reason, Korean parents sacrifice their lives for the education of their children. The clan plays an important role in social and economic relations. It is not uncommon for a core of Korean firms to be staffed by family members, distant relatives, people from the hometown, or graduates of the same university; and it is not unusual for firms to be managed like quasi-family units (Kim, 1997: 69). Harmonious interpersonal consensus-based relations are emphasized. Interpersonal relationships are defined in terms of social status, such as gender, age, and position in the society. Social etiquette is well defined when it comes to interactions among people. Harmony, which refers to respect for other people and a comfortable atmosphere, plays a very important role in Korea, where people try to avoid or minimize face-to-face conflicts. Harmonious interpersonal relationships are mainly built on seniority. Harmony is reached through cultivation and adaptation of one’s self (Rowley, Sohn, & Bae, 2002: 72–73).

The emphasis on personal loyalty to those of higher rank is of vital importance—for example, when working at Samsung. A supervisor can practice massive criticism to a subordinate, while the other way around, unconditional loyalty, obedience, and untiring deployment of labor are expected. This is in accordance with the strict discipline already practised first at school and later at work as well as in the entire social life. Discipline combined with loyalty, moral obligation, severity, and benevolence contribute to business competitiveness (Chen, 2004: 42). It is of vital importance that these attitudes, which reflect the company culture, are respected and shown by each Samsung employee in daily life at work. Samsung staff members do not argue in front of their boss and, instead, are ‘action-oriented’ and busy (in order to realize the boss’s order). Despite the challenges and mental pressure at work, Koreans have a positive attitude towards the future that favors realizing the permanently increasing business goals launched by the Samsung management (Kim, 1997: 68–69).

The Korean culture is fundamentally influenced to a greater degree by historical and philosophical Chinese thought than, for example, is the case in Japan. The philosophical values of old Chinese military strategists were transferred to the business community. The Chinese expression ‘Shang Chang Ru Zhan Chang’ is translated to mean ‘the marketplace is a battlefield’ (Chen, 2004: 33). Several Asian business leaders have attached great importance to classical Chinese military strategies. Many of the principles behind these strategies are commonly applied to business activities, of which Samsung serves as example.

According to the idea of paternalistic leadership, Chaebols are controlled by their founders or owners (Samsung: Chairman Lee Kun-hee) and their families, who usually have enormous influence not only on the organizational culture but also on business strategies. In business, decision processes, and strategies, the Samsung management is target and goal oriented. Consequently, the company pursues a permanent trade-off between the regional advantages and weaknesses at plant locations around the globe. The management of the Samsung headquarters (located in Seoul) is free to intervene in any subsidiary at any time. According to Rowley et al., military structure contributes heavily to ideas about how business organizations should be designed and operated. This orientation influences behavior, predisposing companies to emphasize hierarchical command, a result-oriented ‘can-do spirit’, and competition among the employees (Rowley et al., 2002: 75). The hierarchical work atmosphere at Samsung was described by one Samsung employee as follows.

There are a lot of unscheduled and sudden orders with an urgent due date from the top management and CEO. Even if managers do make a false decision or mistake or give inappropriate orders, employees do not reject it or speak out loud to say it is wrong. Koreans are quite used to being told and directed by managers (or teachers) about what they should do ever since they were teenagers at school and, therefore, very often have a lack of creativity and are afraid of trying new things and breaking rules (Glowik, 2007c).

Koreans rely heavily on personal relationship networks that are embedded in blood relations, growing up in the same region, similar academic background, or the university attended. According to an empirical study by Chang and Chang (1994: 51), Koreans have most confidence in members of their own family, followed by high school classmates and people from the same region. In contrast, Koreans do not trust Korean strangers and foreign people. Due to their long history as a relatively homogeneous ethnic group, Koreans have a high level of communication based on shared contexts (high-context society). They like to convey information through nonverbal cues embedded in physical settings or internalized in particular personal relationships (Rowley et al., 2002: 74).

The Western scientist Hofstede (2001: 215) describes Korea as one of the most collectivist countries in the world. However, Asian scholars like L. Kim (1997: 69) indicate that Koreans are more individualistic than, for example, Japanese (Chang & Chang, 1994: 45). Western expatriates of multinational companies often presume collective attitudes in Korean managers but recognize individualistic, even egotistical, forms of behavior. Koreans have a strong tendency to distinguish themselves from others and show collectivist behavior only to people of the ‘in-group’. Among Koreans, communication is more personalized and smoothly synchronized, which is the opposite in the case of communication with ‘out-group’ members (Rowley et al., 2002: 73).

From the Korean point of view, the success or failure of business reflects one’s ‘own face’ and directly influences the survival of the private family and, consequently, the prosperity of the whole nation (Chen, 2004: 33). According to Kim and Bae (2004: 139), compared with Western enterprises, Korean firms give more weight to human nature – for example, personality, behavior and company-culture integration – than the purely job-related competence of an employee – for example, performance, achievements, and expertise (Kim and Bae, 2004: 139). This attitude differs from Western cultures, where company performance (expressed rationally in profit or loss figures) and private life are perceived as separate matters. Koreans see the company’s prosperity as a private matter and, consequently, view it more emotionally. In the case of Samsung, this is reflected in the strong motivation of the employees. As one Samsung staff member commented to me during an interview in Seoul:

A task or project is to be done by a due date; all team members are devoted to completing the job as fast as possible by dividing the work. The strengths of Asian-based companies are personal relationships and networks, team work, and self-sacrifice. In Europe, work and personal life are completely separate and isolated. After work, employees do not go together for a further casual discussion. Work time is very rigid and inflexible. At 06:00 p.m., no one is present at work because they have gone home. Europeans have long vacations.

‘The person in charge is on holiday for three weeks; therefore, the job cannot be done at the moment. Please wait’.When a Korean business partner listens to such information on the phone and is confronted with such a situation, he or she is speechless. Speed is the key in the twenty-first century, especially in high-technology industries such as the electronics business (Glowik, 2007c).

If the profit of a business segment tends to drop, countermeasures follow from the Samsung management immediately. These activities contain restructuring programs, reduction of employees, and shut-down of production lines or whole plant facilities as was the case in Wynyard, Great Britain, in 1998; Berlin, Germany, in 2006; Tschernitz, Germany, in 2007; and Goed, Hungary, in 2013 (Samsung, 2014a; Zschiedrich & Glowik, 2005: 323). As the company slimmed down during the financial crisis in Asia from about 1997 to 1999, around 30 percent of the employees lost their jobs (Genser, 2005: 3). In the spring of 1998, approximately fifty middle-level managers in the manufacturing plant in Busan (South Korea) took ‘early retirement’, which can be regarded as a de facto layoff program (Kim & Bae, 2004: 185). The financial crisis in Asia caused the number of regular production workers in the Busan plant to be decreased from approximately 7,000 to 5,000. Wages were cut by around 10 percent, and benefits like summer vacation allowances were abolished or temporarily restricted. At the end of 2006, several managers at the plasma television set business division in Korea had to leave the company due to a sales performance that was lower than expected by the top management (Kim & Bae, 2004: 185).

Restructuring activities like those described above more closely resemble US conditions than traditional Asian management behavior. The influence of the US after World War II – for example, liberalization from Japanese occupation, military support of South Korea during and after the Civil War (1950 –1953), and considerable financial aid—have obviously made the country open to Western management styles. Korea’s business elite has a preference for Western ways of thinking, which encouraged learning from industrialized countries along with imitation of advanced technology and management. This is connected to traditional behavioral values like positive attitudes towards hard work and lifelong learning, which has contributed to the successful performance of Samsung. Employment fluctuation, for example, is comparatively much lower at Samsung than in most US-based enterprises (rather short-term oriented, e.g., quarterly reports) or in Chinese firms (rapid economic growth). Compared to Japan, the human resource management practice at Samsung could, therefore, be described as a ‘semi-lifelong’ employment policy (Chen, 2004: 193).

Unlike its biggest rival, LG Electronics, Samsung is a non-union company. The non-union philosophy was influenced by the founder of Samsung, Lee Byung Chul (Kim & Bae, 2004: 183–184). Representatives of German trade unions reproached Samsung for selecting production locations based on the volume of subsidies. For instance, after subsidies by the local Berlin government expired in March 2006, production at Samsung SDI Germany was shut down; and 700 employees were dismissed. Samsung SDI Hungary, established in 2002, assumed production from Germany. The Hungarian government supported the investment with considerable tax incentives. A couple of years later, the Hungarian plant was shut down (Jacobs, 2006; Wohllaib, 2006: 1). Nevertheless, Western enterprises do not differ very much in that way. For example, the Finnish Nokia in 2008 closed its mobile phone manufacturing in Bochum, Germany, and transferred it to Rumania, where considerable subsidies were paid. And there is another historical aspect to consider. After the Korean Civil War, Korean Chaebols such as Samsung, LG Electronics, Daewoo, and Hyundai grew successfully because of the fundamental financial support of the South Korean government, among other reasons. Thus, deciding on investment activities based on the size of tax incentives is neither immoral nor exceptional for Korean managers.

3.2.2Strategic relationship building

Japanese companies made an essential contribution to the construction and development of Samsung. In 1969, a joint venture with Sanyo (Japan) was agreed upon, which later led to the founding of Samsung Electro-Mechanics. Samsung Display Devices is the result of a joint venture with Nippon Electric Company (NEC), Japan, which was established in the same year. The foundation (1969) and development of Samsung Electronics, nowadays one of the most important business divisions of Samsung Group, was supported by Japanese companies that were involved by contributing essential technology and management know-how transfer. As a result, the first black-and-white television set was produced in 1971 by Samsung (Samsung, 2007).

The international joint venture Samsung Corning Precision Materials, which is a manufacturer of high-quality glass parts for the production of displays, resulted from an agreement between Corning Inc., USA (e.g., assembler of today’s well-known ‘Gorilla glass’) and Samsung in 1973. Major production capacities for the glass used in smart phones and television sets are located in South Korea, China, and Taiwan. As a result of the joint venture, Samsung Display will secure LCD screen glass supplies from Corning until 2023. Corning holds the joint venture majority ownership positioning (Corning, 2013). The international joint venture between Corning and Samsung has been further developed over decades and serves as one of the rather rare existing examples of successful and long-term Western-Asian international joint ventures.

Samsung’s continued relationship-seeking efforts brought it into collaborative arrangements with the world’s technologically leading firms. For example, in 1994, it was announced that Samsung and the Japanese NEC would share development efforts at a cost in excess of USD one billion to bring a 256 M DRAM to market in the late 1990s (Lynskey & Yonekura, 2002: 282). In 2001, Samsung and NEC agreed upon a new joint venture called Samsung NEC Mobile Display OLED. The main target of the joint venture was to join efforts to develop the OLED business. Samsung and NEC can rely on their long-term experience in running joint ventures, which has been developed for decades. Over time, various additional technological alliances have helped develop Samsung into one of the leading firms in consumer electronics. Samsung’s top management has continuously searched for new market potentials for the future and strengthened its efforts to establish selected alliances, such as with Nokia (2007, mobile phone technologies), Limo (2006, Linux-Platform), IBM (2006, industrial print solution), and Bang and Olufsen (2004, home cinema systems), just to mention some of Samsung’s alliances (Samsung, 2008b).

Since the 1990s, the competition between South Korea and Japan in the field of electronics has become intense. Although South Korea’s electronics industry, which grew by introducing Japanese technologies, was behind that of Japan in the initial phase, South Korean companies, with Samsung as a representative, made innovations on the basis of digestion and assimilation. For example, in 2004, Samsung and Sony decided to establish the joint venture S-LCD Corporation and shared the output from the ‘seventh-generation’ LCD factory (Genser, 2005: 3). At this time, Samsung was technologically already ahead of Sony in flat panel production. Samsung’s newly gained position as a serious rival was one of the major reasons that Sony did not prolong the joint venture with Samsung and, instead, started to collaborate intensively with Sharp in the LCD panel television set business (Otani, 2008). As a result, Samsung acquired all of Sony’s shares of S-LCD Corporation in 2011, making S‐LCD a wholly owned subsidiary of Samsung. Meanwhile, in terms of capacity and technology, Samsung successfully exceeded several Japanese firms in the fields of display panels, smart phones, and semiconductor production (Kim, 1997: 193; Sony, 2011).

In 2007, Samsung signed an alliance agreement with LG Electronics, its biggest rival and the ‘ever number two’ of the Korean electronics industry and competitor in the global display market. Samsung and LG decided ‘to join forces to challenge the market’ as was stated in the corresponding press release (CDRinf, 2007). The firms pledged to cooperate in various fields, ranging from patents and joint research and development to cross-purchasing of panels from each other. The alliance, furthermore, contains a mutual component supply providing selected products, and seeks to standardize panels, equipment, and materials. In addition to this, both panel manufacturing giants have reached an agreement to proceed in the future with a ‘small-to-large’ joint development strategy for the display industry through the project of Eight Win-Win Partnership, which concentrates on ‘patent cooperation, mutual vertical integration, and joint research and development activities’. Korea’s commerce and industry minister, Kim Young-Ju, said the following during a meeting of anti-trust regulators:

The alliance should not be seen as setting the stage for collusion or price fixing. The companies are not seeking mergers or a cartel to fix prices. South Korea should ease tight antitrust rules to help local firms compete with foreign rivals through strategic tie-ups. Samsung and LG jointly account for some 40 percent of the global market for display panels, about the same as Taiwan; and Japan takes up the remaining 20 percent. The moves are seen as a way to battle aggressive competition by Japanese rivals and alliances among Japanese and Taiwanese companies. Japan’s Sharp Electronics and Taiwan’s Chi Mei Optoelectronics (CMO) and Chunghwa Picture Tubes agreed to share patents last year. But Samsung and LG depend heavily on Japanese parts for their product (CDRinf, 2007).

In recent years, Samsung has accelerated its relationship efforts with other firms doing business in promising future markets, such as batteries (e.g., electric cars) and medical devices. For example, in 2008, Samsung established an international joint venture called SB LiMotive Co. Ltd. with the German Robert Bosch GmbH for the development, production, and sales of lithium-ion battery systems. Robert Bosch GmbH and Samsung SDI each invested 50 percent in that international equity joint venture. The management and the supervisory board consisted of an equal number of appointed members from both enterprises (Samsung, 2008a, b). The knowledge developed and acquired from the joint venture of Bosch and Samsung is applicable for batteries used in electronics devices and cars. However, in 2012, Bosch withdrew its stake in the joint venture due to ‘strategic differences’ with its joint venture partner (Hammerschmidt, 2012). Probably, Bosch became aware of the risk that Samsung would gain car battery as well as electric car management knowledge, which would help Samsung become a powerful competitor to Bosch in the promising future electric car business.

As a consequence of the international joint venture termination with Bosch, Samsung SDI announced the acquisition of the battery pack division of Magna Steyr International in 2015, which will further solidify the company’s foothold in the automotive market. The agreement to buy Magna Steyr includes all 264 employees as well as the current business contracts and all production and development sites. The division is based out of Austria and builds battery packs for electrified vehicles. With the acquisition, Samsung will focus on growing customers in the electrified vehicle markets in North America, Europe, and China. By 2020, Samsung predicts that this market will reach 7.7 million vehicles worldwide. Capacity enlargements are currently underway for a new Samsung plant in China. After its opening at the end of 2015, the factory will be capable of supplying batteries for more than 40,000 electrified vehicles (Shelton, 2015). Samsung SDI currently supplies cells to BMW for its i3 and i8 plug-in cars (Gastelu, 2015).

Interestingly and less known in Western countries, Samsung had already held a foothold in the automotive industry since the end of the 1990s when Samsung agreed with the Japanese Nissan to build a version of the Maxima, called the SM5, which went on sale in 1998. As a result of the Asian financial crisis, which affected Nissan too, Renault from France acquired around 43 percent share of Nissan and, as a consequence, Renault Samsung Motors was established. As per 2015, Samsung holds 20 percent of Renault Samsung Motors (Gastelu, 2015).

3.2.3Diversified organization

A corporate strategy mirrors organizational processes that are inseparable from the structure, behavior, and culture of the company (Andrews, 2003: 73). Company growth in industries unrelated to the current business through diversification strategies is a significant characteristic of all Korean Chaebols. Historically, diversification strategies have been widely advocated and supported by the Korean government. Samsung entered into wood textiles and sugar in the 1950s ; fertilizer and paper production started in the ’60s ; construction, electronic components, heavy industry, petrochemicals, and shipbuilding were entered in the ’70s ; and aircrafts, bioengineering, and semiconductors were introduced in the ’80s (Chen, 2004: 187–188). More recently, Samsung entered medical devices (healthcare) and automotive industries.

Samsung’s strategic advantage in today’s business lies in its highly diversified activities, which allow aggressive market entry and penetration strategies because temporary losses in foreign markets are compensated by a continued flow of revenues in the native country, where the company has a dominant position. Although the financial, legal, and organizational encouragement by the Korean government to strengthen the Korean Chaebols is lower nowadays than in earlier decades, Chaebols still have several advantages due to their size and importance for the country’s economy. Samsung has a quasi-monopoly position in many areas. For instance, there is the luxury Hotel Shilla in the capital of Seoul. Samsung Everland, a large entertainment and amusement park, follows the US example of Walt Disney (Samsung, 2004). Cheil Communications, South Korea’s largest advertising agency, as well as insurance and credit card businesses, petrochemicals, construction, and others also belong to Samsung Group. In recent years, in addition to its strengthened electronics business, Samsung has become involved in automotive and the promising healthcare-related industries (e.g., medical devices).

Another characteristic of Korean Chaebols is the mutual shareholder participation of the diversified businesses, and the Samsung Group serves as an excellent case. As illustrated in Figure 34, Samsung Electronics holds the highest shareholder percentages in the other business units, which underlines its important role for Samsung Group. In other words, due to its strategic importance, if the electronics business suffers, the entire Samsung organization may start swinging.

Figure 33. Diversified organization [status 2014] of Samsung Group (Dutton, 2014; Samsung, 2014a)

Figure 34. Mutual capital participation of the diversified business units of Samsung Group (status 2014). Source: Developed by the author based on 2013 and 2014 annual reports and further firm-related information of Samsung

Lee Kun-hee, chairman of Samsung Group, and his family own less than 5 percent of the shares of Samsung Electronics directly. Nevertheless, they are able to control Samsung Electronics because of the circular equity structure within Samsung Group, such as Samsung Everland, Samsung C&T, and Samsung Insurance. The total shares in these companies held by Lee and his family are worth about Euro 10 billion (status 2012). Lee and his family exercise absolute management authority (Han, Liem, & Lee, 2013: 4).

Samsung realizes various advantages accruing from these diversified product lines. One obvious benefit is the resulting diversified business risk. Because the company’s products spread out into many fields, it is more effectively able to cope with the ups and downs in particular product markets; and this helps the company to develop its sales performance, which reflects the company’s growth strategy in the global markets. Another advantage is the cross-product component sharing, which is important when different products are converging onto the same platforms (Chen & Li, 2007: 77). Large manufacturing facilitates help spread the costs of research and development and allow realization of overall economies of scale effects.

Figure 35. Net sales and net income of Samsung Group for the period 2003 to 2014 (Samsung, 2015)

Successful growth provides the chance to take advantage of the experience curve in order to reduce the per-unit costs of products sold. The sales development of Samsung Group has shown an outstanding sales performance over the last years relative to its competitors. However – for example, compared to the industry benchmark in terms of profit margins, which is currently Apple Inc. (USA) – Samsung’s management has not been able to expand net income with the same growth rates. What might be the reason for this shortfall? First, Samsung is embedded in various and diversified business fields and owns facilities that have enormous fixed costs. Thus, taking the risk of running overcapacities, the firm becomes vulnerable in the case of economic downturns in the worldwide markets. In this situation, Samsung sells its products at relatively marginal price levels in order ‘to feed the production lines’ (bfai, 2007). Second, the electronics industry, which is the core business of Samsung Group, is highly price competitive. Permanent product innovations are necessary to secure the firm’s business destiny for the future. The corresponding investment volume in research and development as well as large-scale manufacturing capacities has been increased in recent years.

There is no doubt – relative to its Japanese rivals, such as Sony, Sharp, and Panasonic – that Samsung has reached a more stable and prospective business performance during the last years. Samsung has concentrated on its core competence, the electronics business. The firm invested early in LCD/ LED displays and smart phone production capacities at a time when the market potential had been neglected by others. In addition, Samsung Electronics has been expanded in several vertically integrated business segments. The complete manufacturing capacities of television sets, semi-conductors, and mobile phones belong to the most important strategic business segments of Samsung (BBC, 2008; Samsung_Electronics, 2008). Samsung’s vertical integration is described in more detail in the following section.

3.2.4The strategy of vertical integration of Samsung Electronics

Samsung Electronics is the flagship company of Samsung Group, which is composed of 516 companies worldwide. Out of 516, 195 are full fledged Samsung Electronics subsidiaries, meaning they are incorporated entities of which Samsung Electronics owns more than a 50 percent share. In addition, Samsung Electronics controls an additional 63 companies that make components for its subsidiaries, although it does not own a majority share in them. Smart phones, television sets, and more than 260 additional products under the Samsung Electronics brand are produced and sold through Samsung Group’s network (Han et al., 2013: 3).

The strength of Samsung Electronics is the company’s efficient use of its worldwide vertically integrated research and development, procurement, manufacturing, and sales network. Vertical integration means a firm utilizes an internal transfer within the organization of intermediate parts that a firm produces for its own use, such as materials, components, semi- or completely assembled products, and services. A firm may integrate backward and start generating value added activities it previously procured from outside suppliers. Alternatively, a firm may integrate forward and start integrating products and services, such as a sales and distribution or after-sales service, in order to be closer to the firm’s customers and their ‘voices’. Both of these processes represent methods of a firm’s growth strategy (Penrose, 1995: 145).

Figure 36. Organization [status 2014] of Samsung Electronics (Samsung, 2014b, c; Samsung_Electronics, 2014b)

After the Korean Civil War, during the second half of the 1950s, the Korean government started to route Chaebols into particular industries without building the infrastructure of component suppliers or supporting services. Since the Chaebols found it difficult to purchase or otherwise secure the necessary materials and components and the Korean government pushed domestic firms to industrialize, there were clear and seemingly inevitable reasons to integrate vertically. Differences in the Chaebols’ use of vertical integration stem from the distinct characteristics of the industries the conglomerates are involved with (Chang, 2003: 113–118). For example, in the case of smart phones and television sets, Samsung Electronics controls almost all stages from research and development, to manufacture, up to worldwide sales and distribution. In comparison to Western enterprises, such as Philips or Apple, the Korean firm indicates a much deeper grade of vertical integration. Figure 37 illustrates the vertically integrated value added activities of Samsung Electronics regarding a state-of-the art LED television set.

Figure 37. Samsung’s vertical integration in terms of value added activities of an LED television set

As illustrated above, Samsung Electronics is closely interlinked with Samsung Display, a manufacturer and key supplier of displays for television sets. Samsung Display can rely on Samsung Corning, which produces the screen glass for the displays. Samsung Electro Mechanics delivers components for the display assembly. An LCD/ LED television set is based on a combination of display and semiconductor technology. Firms like Samsung, with a strong background in both display and semiconductor technologies, are in a comfortable position to manufacture state-of-the art television sets (Kim, 1997: 144). Vertical integration helps Samsung maintain better quality control and delivery punctuality than the company could achieve through outsourcing. Furthermore, vertical integration means that the fruits of research and development in one stage of production are more likely to be shared with other stages, thereby increasing the overall competitiveness of both upstream and downstream operations. Nowadays, the main part of Samsung Electronics’ sales is conducted directly with the customers who serve as the firm’s major information source in terms of the design and desired product features. Through its vertical integration, Samsung Electronics is able to launch its products more rapidly on the global markets than most of its competitors (Chang, 2003: 120–121; Kim, 1997: 144; Worstall, 2013).

Figure 38. Net sales and net income of Samsung Electronics for the period 2003–2013 (Samsung_Electronics, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014a)

As illustrated in Figure 38, Samsung Electronics performs well in terms of net sales and net income and is much better positioned than most of its Japanese competitors. Nevertheless, vertical integration also comes along with potential challenges. One of the potential hazards to efficiency comes from vertically integrated suppliers who lack the incentive to be more efficient or innovative because they have captive in-house customers (Mahoney, 1992: 559). This lack of incentive can be severe in the case of Chaebol affiliates because large portions of their sales are transferred internally (Chang, 2003: 122). One’s own component production may be less efficient relative to its procurement from outside supply sources. Internal price discussions can lead to wasted time and effort (Roberto, 2009).

In the worst case, financially troubled affiliates can survive only with support from their parent company, which guarantees production volumes. The internal charges between the company units are higher prices than the market average. To create a homogeneous group culture and facilitate the inter-group transfer of personnel, Chaebols use the same level of benefits for all business units, which are often too generous for poorly performing businesses, and support unprofitable affiliates via various forms of internal transactions (Chang, 2003: 122–123). The permanent challenge for Chaebols like Samsung is favoritism, which leads to buying from within and hinders competition as well as the input of fresh, innovative business ideas from group outsiders. The top management of Samsung obviously recognized this danger and started to run each business unit as a separate profit center, which supports competition with outside suppliers for orders up to a certain budget. In some cases, up to one third or more of product demand is procured from Samsung’s outside sources, even if it could be supplied in-house.

The system of component production and supply for Samsung Electronics is made up of five layers. The first layer is composed of Samsung Group subsidiaries and accounts for around ten percent of the value of the components purchased by Samsung Electronics. The second layer is made up of transnational electronics component suppliers who have independent technical capability. The US-based Qualcomm, which has a CDMA patent, and 3Com, which has a wireless patent, are examples of companies in this layer. The third layer comprises suppliers to which Samsung Electronics outsources parts production that it could produce by itself but chooses not to for cost or production capacity reasons. These companies – such as Taiwanese AU Optronics for example – supply small-scale LCD panels. The fourth layer is composed of domestic subcontractors that supply parts that Samsung Electronics could not produce itself, such as mobile phone cases manufactured by Intops LED Company Ltd. The final layer in the supply chain is composed of smaller low-cost parts (Han et al., 2013: 6).

Samsung Electronics does not procure and manufacture components only for its in-house uses. It also serves as a vertically integrated, specialised, and large-scale supplier for its major competitors, such as Sony (DRAM, NAND flash, LCD panels), Apple Inc. (mobile processor, DRAM, NAND flash), Dell (DRAM, flat panels, lithium-ion batteries), and Hewlett-Packard (DRAM, flat panels, lithium-ion batteries). Having control over the NAND and controller has major implications both for performance and reliability. Samsung has knowledge of various nuances of these components and can tweak them along each step in the development process to ensure that they work together perfectly. Manufacturers of generic SSD controllers have to worry about supporting multiple NAND specifications (from varying manufacturers who each have different manufacturing processes), while Samsung’s proprietary SSD controller is engineered solely to work with its own NAND – which means engineers can focus all of their efforts towards one common specification. As the most integrated SSD manufacturer in the industry, Samsung controls all of the most crucial design elements of an SSD: NAND, Controller, DRAM, and Firmware. Working together, these components are responsible for a crucial task –storing, stable operating, and protecting precious data (Samsung, 2014d).

As a vertically integrated supplier, Samsung is able to achieve economies of scale and protect its position as a consumer electronics giant by leveraging its ability to produce component parts and assemble its products in a large-scale and cost-efficient process. Samsung Electronics relies on other companies mainly in terms of software applications – for example, Google, which supplies the operating system for smart phones and delivers related applications (Apps). In contrast to Samsung, Apple Inc. is a vertically integrated specialized buyer. Apple Inc. represents four companies in one – a hardware company, a software company, a service company, and a retail company. It controls all the critical parts of its value chain, but leaves the manufacturing process of its electronics components to other companies, such as Samsung. Consequently, Apple Inc. is rather a design company, not a manufacturing company like Samsung Electronics (Vergara, 2012). Samsung’s supplier positioning also poses another risk. The firm finds itself competing with its customers – which are, in parallel, competitors. About a third of Samsung’s revenue comes from companies that compete with it in producing television sets, smart phones, computers, printers, and other items (Ramstad, 2009).

3.2.5International business expansion

As South Korean electronics firms gradually strengthened their presence and expanded their market shares overseas, import restrictions regarding goods from Korea increased in key markets such as the United States and the European Union. By the end of the 1980s, there were restrictions in the form of antidumping duties, quotas, and quality standard restraints on Korea’s major export producers of color television sets, including Samsung. (Cherry, 2001: 65). As a result, Korean Chaebols strengthened their foreign direct investment activities, and overseas expansion through foreign direct investment has been impressive in the case of Samsung Electronics.

During the 1970s, the firm concentrated its manufacturing capacities on its home market, South Korea. The first foreign direct investment outside Korea was done in Mexico and Thailand (1988). In Europe, Samsung built its first television set manufacturing plant in Hungary in 1989. Meanwhile, China, as a manufacturing platform, has played an outstanding role for Samsung. Particularly at the beginning of the 1990s, Samsung Electronics established several manufacturing locations for a wide range of products (e.g., television sets, audio, telecommunication, etc.) in China. The manufacturing capacity expansion, including the foreign direct investment activities of Samsung Electronics, as well as additional details, such as the year of establishment and the manufactured products, are illustrated in Figure 39 for the period 1969 to 2013.

In recent times, such as in 2002, taking advantage of a favorable investment environment (e.g., relatively low costs combined with subsidies from the government), Slovakia was selected as a new investment location for building television set manufacturing capacities in Europe. In 2008 and 2009, Samsung invested in Russia, Vietnam, and Poland, while ‘coming back to Asia’ when it established LCD (2012) and semiconductor (2013) manufacturing capacities in China. Straight from its foundation, the Samsung management obviously has invested in locations where it has forecast promising business opportunities instead of paying too much attention to geographical distance or perceived cultural differences.

Traditional internationalization theories like the Uppsala approach assume that firms follow a linear, incremental internationalization chain pattern (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977: 23–26; Luostarinen, 1980, 200 –201). Interestingly, Samsung has developed its international business, from its beginning, in contrast to the traditional internationalization theories. As can be seen, in the business expansion route of Samsung Electronics, the firm did not follow an incremental, linear investment path from nearby countries located in Asia to more distant countries such as those overseas. Instead, through various joint venture and strategic alliances, Samsung Electronics has gained knowledge from its relationship partners, which rather reflects major characteristics of the network theory of internationalization.

3.2.6Product design, research, and development

Samsung Electronics has continuously increased its efforts to seek a reputation as a premium brand manufacturer. In this regard, Samsung’s advertising campaigns have increased considerably. In Europe, Samsung is rather known for its electronics products but plays a minor role in other businesses, such as heavy industry, insurance, credit cards, and others. Samsung Electronics’ annual budget for worldwide promotion expenditures amounts to around one billion Euro. Such a large advertising budget allows for market-specific and professional campaigns. Additionally, the company does extensive sports sponsoring. In Europe, Samsung’s brand awareness has particularly increased during the last decade. One of the reasons for this is the company’s strategy of single brand marketing, which includes a diversified electronics product range of smart phones, television sets, and other items.

A company that provides a full product range obtains attention and, consequently, easier access to the end consumer. This is an advantage in mass markets such as consumer electronics with relatively standardized products and intense price competition. As a high-technology company that produces various types of products in different segments (e.g., mobile media, semiconductors, home applications), Samsung has to consider that the designing process is one of the fundamental activities in creating value. Since high-tech products are changing rapidly, the corresponding creation of designs is needed in order to compete in the global market (Korea_Associates, 2012: 14). For its product designs, Samsung is running product design centers located in the following countries (compare illustration).

Figure 39. Expansion of Samsung Electronics’ worldwide factory network. Source: Collected by the author as exhibited at Samsung Electronics’ main entrance hall in Seoul, South Korea

Figure 40. Samsung’s worldwide network of product design units. Source: Samsung Electronics (2006: 52) and Korea Associates (2012: 14)

For advanced and research-intensive products, Samsung Electronics still concentrates on its home base in South Korea. In addition to the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology (SAIT) located in South Korea, the network is completed by local research and development centers in various locations around the world (Lynskey & Yonekura, 2002: 283). The technological results are transferred to the headquarters in Seoul, which collects data from similar research units around the world and prepares fine-tuned economies of scale production scenarios for various Samsung factories around the globe. More specifically, the Samsung Electronics research and development activities are organized in three layers. (The first two layers are core to technology development and product planning.)

(1)The Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology (SAIT) ensures Samsung’s technological competitiveness in core business areas, identifies growth engines for the future, and oversees the securing and management of technology including patents.

(2)The research and development centers of each business focus on technology that is expected to deliver the most promising long-term results. Each division of Samsung Electronics has its own research department, but all of these can outsource projects both to SAIT and to third-party institutions.

(3)Divisional product development teams, working with design centers, are responsible for commercializing products scheduled to launch in the market within one or two years.

Samsung Electronics spends about Euro 6 to 10 billion per annum on research and development, which equals about 7 percent of gross earnings. In smart phones, research and design is taking place in multiple centers, with the ‘solution divisions’ in Korea preparing products for external customers like Apple and for its internal customers in Samsung (Korea_Associates, 2012).

Figure 41. Worldwide research and development centers of Samsung Electronics. Source: Korea_Associates (2012: 15)

There is no doubt that Samsung has successfully changed its reputation from a cheap original equipment manufacturer (OEM) to a technology- and marketing-driven company. Samsung’s strength is based on its expertise forecasting future market potentials, which comes along with its major strength: very fast market response times. Despite its diversified business portfolio, further strengths of Samsung lay in its vertical manufacturing depth and in the firm’s fast knowledge absorbing capabilities of strategically valuable information from customers, suppliers, and competitors’ products. The acquired knowledge immediately results in newly developed products and the establishment of vertically integrated economies of scale manufacturing techniques, using regional cost advantages in its own factories – such as those in China and, more recently, in Vietnam. The products are launched through Samsung’s global sales network, usually faster than competitors, which allows further experience curve and learning effects.

Additionally, through faster market entry than its competitors, an impression of an innovative technological pioneer (first inventor) is spread, which is in most of Samsung products still not the case (e.g., LCD/LED TV was mainly developed by Sharp, smart phones introduced by Apple, laptops by Toshiba, Blu-ray by Sony, and so on). Samsung rather holds the position of the ‘second first’, targeting to learn from the mistakes of the others; but this is done very effectively by the largest Korean Chaebol. This absorptive capability, together with its efficient forecasting and market timing, establishes Samsung as a true industry benchmark in high-technology industries.

Chapter review questions

- Describe the major characteristics of the management philosophy of the South Korean Chaebol Samsung and the culturally based strengths and weaknesses in terms of developing the business.

- Explain the historical reasons for, the current business fields of, and the advantages and disadvantages of the diversification strategy of Samsung Group.

- Explain the vertical integration strategy of Samsung Electronics and the corresponding opportunities and challenges for the management.

- Taking today’s perspective, do you think Samsung Electronics holds the position of a technological leader or technological follower in the consumer electronics industries?

- Assuming you are in the shoes of the management, where do you see the future of Samsung Electronics? Explain the reasons for your answer, and provide reasonable arguments.

3.3Foreign Market Entry Strategies

3.3.1Contractual modes of market entry

3.3.1.1Indirect and direct export

Export describes business activities where goods and/ or services are sold outside the country in which the major value-added activities took place. Export allows a fast and relatively less risky foreign market entry. The exporter‘s major risk is a financial risk (importer does not pay for the cargo) that can be reduced by asking for pre-payment before delivery or by using a letter of credit or export credit insurance. By developing the service or manufacturing the products at home and exporting them abroad, the organization is able to realize substantial economies of scale effects from its expanded sales volumes in the foreign markets in addition to its sales in the local market (Hitt, Ireland, & Hoskisson, 2015: 243). Exports help to develop the firm’s international business competence and innovative capabilities due to the firm’s access to information located in foreign markets. According to Love and Ganotakis (2013: 14), knowledge-intensive service-sector firms are able to gain earlier benefits from their expansion to export markets than manufacturing firms.

Basically, we distinguish between direct and indirect exports. Indirect exports and direct exports describe transactions in which the firm delivers products and/ or services to an importing company based on a contractual agreement. Having no, or very little, experience in the business of foreign trade, it is desirable for the firm to initiate its first foreign engagement through so-called indirect exports. This market entry mode is called indirect export because an intermediator, with a commission, searches for potential customers (importers) in the target foreign country. The commission is subject to negotiation between the exporter and the intermediator and usually ranges from two to fifteen percent of the contract value. The commission is due after a contract is signed by the exporter and importer. Because the intermediator searches for pre-negotiated agreements with potential importing customers, the exporting firm is not confronted with challenging socio-cultural conditions, such as unfamiliar negotiation behaviors or language barriers. However, intermediators who run their business based on a commission often carry the products of competing firms and, therefore, tend to have divided loyalties (Hill, 2012: 491).

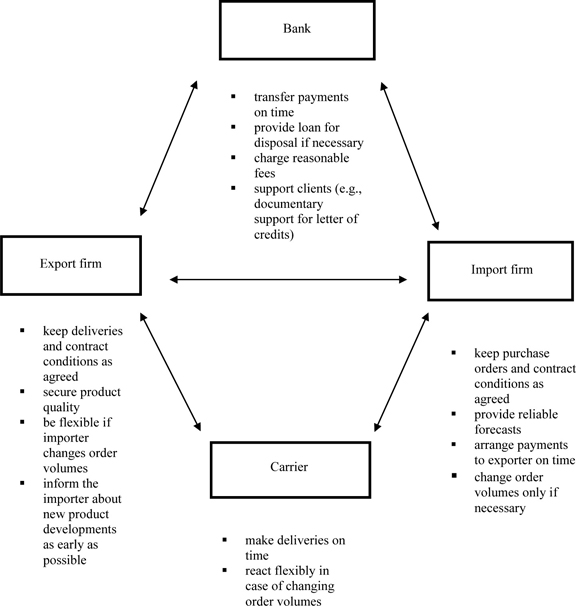

In the case of direct exports, the firm undertakes personal relationships with the importing customer abroad. Direct export requires more resources relative to indirect business because of traveling as well as actively managing the negotiations and contracts. The advantages from direct market access and the benefits from gaining valuable first-hand customer information may easily exceed the costs of active export management. Carriers and banks are important participants in the exporter’s business-to-business network. The carrier’s willingness and degree of resource commitment influence the performance of on-time delivery of the cargo from the exporter to the importer. The bank, through its transfer of timely payments and its fee and loan policy (which is also a result of the bank’s resource commitment), has further significant impacts on the importer’s and exporter’s degree of satisfaction. The mutual resource commitments of the exporting firm, the importer, the bank, and the carrier for a direct export contract are illustrated in Figure 42. A particular form of export without the involvement of a bank is called barter. With barters, products and services are mutually exchanged between exporter and importer without financial payments. The volume of the products exchanged may differ depending on the unit value of each product. Barter businesses come about with firms located in rather fragile regions in terms of the economy, infrastructure, and finance.

The major challenges for a firm doing export business are cross-border trade barriers. Because of liberalized trade patterns as a result of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which became effective in 1948 and was replaced in 1995 by the World Trade Organization (WTO), the average customs import tariffs are lower or disappeared compared to the past. However, nontariff barriers (bureaucratic import documentation), which are more difficult to gain evidence about, may remain a threat for the exporting firm, especially in volatile export target markets where the government of the host country tends to make use of barriers in order to accommodate the domestic industry lobby.

Export easily becomes uneconomical for bulky products and/or long-distance markets, which entail relatively high transportation costs. Furthermore, in light of globalization, firms face the challenges of supply flexibility and efficient management of demand changes in order to gain competitive advantage (Vollmann, Berry, Whybark, & Jacobs, 2005: 588). Exports from geographically distant markets result in a longer transportation lead time and limited response time in case the order is changed by the customer. The after-sales service becomes more difficult and expensive when the manufacturing location is far away from the export sales market. Domestic production and export may not be appropriate if lower cost locations or highly skilled staff for manufacturing and selling the product or service is available abroad or if local manufacturing is supported by infrastructure incentives granted by the local government (Hill, 2012: 491–492).

In the past, products with a relatively high degree of tangibility and a low demand for interaction between producer and final customer were usually exported. In recent years, we have witnessed export activities for products with a high degree of intangibility, such as software development or accounting services. An example is India, known as an exporting country (Blomstermo, Sharma, & Sallis, 2006: 216). E-commerce-based communication, sales, and distribution channels make it possible for an exporter to neither require an intermediator nor be permanently physically present in the target foreign markets. The case study of the upcoming Chinese telecommunication company Xiaomi describes how digital distribution is applied in order to successfully enter foreign markets.

3.3.1.2Contract manufacturing

3.3.1.2.1How it works?

In highly competitive and technologically fast changing industrial environments, manufacturers often consider establishing production capacities in a foreign market. The major reasons for market entry through contract manufacturing (synonymous term: original equipment manufacturing) are the following: a firm takes advantage of lower-cost locations and is able to save logistics costs due to local manufacturing in the target foreign market. The original equipment manufacturing (OEM) strategy allows the brand manufacturer a faster market entry abroad via the contracted firm than through foreign direct investments. This is particularly the case in high-technology industries where product innovations, simultaneously launched on a global scale, are of vital importance in order to gain competitive advantage. While the original equipment contractor (OEC) firm concentrates on the production, the brand manufacturer can bundle the resources in its core competencies, such as research and development or marketing. In other words, contract manufacturing is linked to the ‘make-or-buy’ question (Morschett, 2005: 599, 610). The OEC can combine production for several OEMs and thus realize economies of scale (Plambeck & Taylor, 2005: 133–134). Further incentives for contract manufacturing from the OEM’s perspective are improved sensitivity to local customer needs and avoidance of host country import taxes or quota restrictions (Hollensen, 2014: 369).

How does the OEM system work in practice? The OEM (brand manufacturer) searches for a potential firm in the foreign target market that is able to manufacture, based on the OEM’s desired cost structure, the technical specification and quality standards of the OEM’s products. When the OEM has found a suitable and capable firm, a contract is signed; and the OEC starts production of quantities of the OEM’s product. It is important to mention that the OEC puts the OEM’s brand name on the product at the end of the assembly process. Because the brand is visible on the product, consumers do not realize the product is assembled by the OEC. However, consumers are usually charged at the same price level (market goodwill of the OEM’s brand) as they are used to paying when it is manufactured by the OEM. The lower unit manufacturing costs (because the product is manufactured by the OEC) but higher sales price (as though it was manufactured by the OEM) finally generates higher OEM margins.

According to the conditions (everything is negotiable) between the contracting parties, the OEC may launch individual component assembly operations (semi-products) or manufacture the complete products including services (full operations). Payments by the OEM to the OEC are generally calculated on a per unit basis. In many cases, the OEM contracts with different OECs located at different places around the globe. Thus, the OEM benefits from each OEC’s proximity to the market, which results in an increased flexibility to balance the production capacities of each OEC, if necessary (Hollensen, 2014: 369). This close proximity helps to accelerate the OEM’s time-to-market responses in case of fluctuating order volumes. Additionally, contract manufacturing enables the OEM to undertake foreign operations without making a final investment commitment in the foreign target market. As a result, the OEM reduces its investment risk through its contractual agreement with the OEC (instead of establishing its own operations). The contract between the OEM and OEC can be terminated at any time – for example, if sales volumes in the target foreign markets shrink (Cole, Mason, Hau, & Yan, 2001: 7).

Figure 43. Mutual commitments of OEM and OEC

How about the potential drawbacks of contract manufacturing? Disadvantages for the OEM can derive from the OEM’s loss of direct hierarchical control of the manufacturing and administrative (such as quality control) processes. The ongoing fulfillment of quality, based on the technical specification set by the OEM, is of vital importance. In case the OEC does not meet the quality or working condition standards as agreed upon in the contract, this failure may cause serious damage to the OEM’s reputation in the markets. Thus, partner selection, contract negotiation, and quality control procedures have great importance (Hollensen, 2014: 369).

Furthermore, there is a risk for the OEM that the cost and desired benefits become unbalanced because of transaction costs related to the contract partner’s selection process and negotiation procedures (ex-ante costs) and ex-post costs, such as monitoring and control of delivery punctuality, assembly quantity, and assembly quality (Williamson, 1991: 279). The more OEM activities initiated by the original brand firm, the higher the complexity, which provokes expanded information and communication structures. The original brand manufacturer has to decide which value-added activities (products and services) are transferred to a contracting firm. There is another risk when the OEM outsources activities that contributed to the ability of the OEM in the past to differentiate itself from its competition (Kita, 2001: 1). In the worst case, core competencies of the brand manufacturer are transferred to the OEC. As a result, the OEC acquires knowledge through its absorptive capability, which helps to develop the overall manufacturing and business expertise of the OEC. Thus, after a certain period of time, the OEC may become a competitor to the OEM on the global markets by learning from its OEM contracting partner.

The terms contract manufacturing and outsourcing should be clearly separated. The first serves as a method for increasing the OEM’s manufacturing capacities at home by utilizing the OEC’s capacities in the foreign target market (manufacturing activities continue at the OEM).

If, however, the OEM decides to terminate the manufacturing of a certain product at its home base and, instead, shifts the entire production to another firm, this is called outsourcing. In contrast to internal sourcing of materials, components, or products and services within a firm, outsourcing is the process of employing an external provider to perform functions that could be performed in-house (Bertrand & Mol, 2013: 751; Potkány, 2008: 53).

Outsourcing enables a firm to flexibly handle its customer-order management. The firm’s manufacturing capacities are located outside the firm’s hierarchy as an alternative to owning the production facilities. The management is often better able to focus on its core competencies, such as marketing or research and development, to achieve competitive advantage (Cheng, Cantor, Dresner, & Grimm, 2012: 890). Experience curve effects and the specific manufacturing expertise of the contracted firm enables the company to perform tasks more effectively (Caruth, Pane Haden, & Caruth, 2012: 5–6). Outsourcing may help to reduce the fixed costs of the internal manufacturing facilities and thus lower the breakeven point, which helps to improve a firm’s return on equity (ROE). Suppose a corporate executive’s performance is evaluated on the basis of the contribution to the firm’s ROE; the management tends to have a strong incentive to increase outsourcing (Kotabe & Murray, 2004: 7–10).

However, the more the brand manufacturer shifts value-added activities to contracted firms, the less the brand manufacturer is involved in the value-added activities processes. The engineering expertise; technological knowledge; and, finally, the innovation capabilities and quality consciousness of the branded firm incrementally decreases over time. Further potential drawbacks of shifting value-added activities to outside firms are changes in employee morale and erosion of organizational loyalty. An organizational-cultural misfit between the contract partners may lead to a lower product and service quality, which damages the brand manufacturers reputation (Caruth et al., 2012: 6).

In the case of Philips (The Netherlands), it became increasingly difficult to remain efficient and innovative concerning new product developments in the consumer electronics industry. In 2008, Philips announced that it would transfer more than 70 percent of its television set manufacturing orders to contract manufacturers such as TCL Corporation (China), TVP (Taiwan), Hon Hai Precisions (Taiwan), and Funai Electric (Japan). In parallel, these previously rather less-known Asian-based electronics firms strengthened their technological and manufacturing expertise through learning during contract manufacturing relationships with OEMs such as Philips, among other reasons (Digitimes.com, 2008). Around five years later, in 2013, Philips sold the remnants of its audio, video, multimedia, and accessories activities to Japan’s Funai Electric for Euro 150 million in cash and a brand-license fee. The Dutch group reported the management targets of becoming primarily a maker of healthcare, medical equipment, and lighting products and, thus, terminated its once-core business of consumer electronics (Van den Oever, 2013). Other ‘international latecomers’, such as Flextronics of Singapore and Hon Hai Precision Foxconn of Taiwan, successfully used contract manufacturing as a learning tool on their way to becoming major players in the electronics industries (Tung & Wan, 2012: 3–4).

3.3.1.2.2The case study of Foxconn/Hon Hai Precision Industry Company (Taiwan)

In 1974, the Taiwan-based firm Hon Hai Precision Industry Company, better known in Western markets by the name Foxconn Technology, was founded by Terry Gou (Hon Hai Precision Co., 2013). During the first years of its existence, the company produced channel-changing knobs for television sets. In 1988, it began to invest in mainland China by establishing production locations in several regions of the country and by expanding its business to computer assembly. Nowadays, Foxconn is the largest original equipment manufacturer (OEM) in the world (Yiwei, 2014).

Foxconn manufacturers and delivers components, modules, and services and provides solutions ranging from the design and manufacture of components and system assembly to maintenance and logistics (Hon_Hai_Precision_Company_Ltd., 2013). As the largest contract manufacturer, especially for global consumer electronics companies, Hon Hai Precision Company employs about 1.5 million people in China. The enterprise is the major assembler of PCs for Hewlett Packard, Dell, and Acer; and it manufactures iPhones and iPads for Apple Inc., PlayStations for Sony, the Nintendo Wii, and Amazon’s Kindle Fire. Moreover, TVs for Sharp, Sony, and Toshiba are produced at Foxconn factories (Kan, 2012). Foxconn represents one of the largest suppliers for Apple Inc. About 40 percent of its revenue is generated by the OEM partnership with Apple. Apple’s relationship with Foxconn is so extensive that the Taiwanese firm has been building factories for the exclusive purpose of assembling Apple products (Kan, 2012). In 2013, sales hit a record high of USD 130.8 billion; and the company’s net income rose to about USD 3.5 billion (Agence_France, 2014).

Figure 44. Organization [status 2013] of Foxconn (Cai, 2012; Hon_Hai_Precision_Industry Co., 2013)

Nevertheless, in recent years, several scandals erupted because of labor rights violations at Foxconn factories. In addition to miserable working conditions, including overtime issues, unpaid wages, and accidents, suicides of employees were revealed in the media. Finally, Hon Hai and Apple Inc., the most important buyer of Foxconn products, were forced to implement reforms that included a reduction of working hours, overtime wages, and safety procedures in order to improve the poor reputation of both companies. The Fair Labor Association was hired to control working conditions (O’Toole, 2013). In recent years, Foxconn announced several times that robots would be utilized in the production line in order to raise efficiency and decrease labor costs. This change could also be a chance to distance the company from accidents, suicides, and other conflicts at the factories (Mozur & Luk, 2012).

China Labor Watch released a report about conditions at ten factories in China, including the ones operated by Foxconn, Quanta, Catcher Technology, Samsung, and Compal Electronics. According to Debby Chan, a project manager for the Hong Kong-based Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehavior (SACOM), ‘We never said that Apple was the worst in the industry. Samsung, HTC, Motorola, Amazon, and Nokia have the same problems’ (Kan, 2012).

SACOM has been one of the most vocal advocates for change at Foxconn. The issue was first raised in 2010, when a string of worker suicides prompted former Apple CEO, Steve Jobs, to defend the supplier. In a widely reported email, Jobs said, ‘Although every suicide is tragic, Foxconn’s suicide rate is well below the China average’. Since then, Apple has taken a more active role in addressing problems at Foxconn factories – for example, by working with the Fair Labor Association to audit facilities for labor violations. While labor groups remain unconvinced that the progress is sufficient, Apple’s influence over its suppliers could help improve working conditions in factories across China. In addition to Foxconn, Apple uses 155 other suppliers, some of which have also drawn allegations of poor working conditions (Kan, 2012).

Chapter review question

- Describe the opportunities and challenges, from the perspective of Apple’s management, of working with Foxconn.

- How do you evaluate Foxconn’s potentials for its future business?

3.3.1.3Licensing

Contractual licensing relationships describe the transfer of knowledge between one licensor and usually various licensees. The licensor, as the owner of knowledge – for example, concerning a product technology – needs to have a registered patent or trademark, which legally protects the licensor from illegal use of its intellectual property.When applied as an international market entry mode, the licensor grants exclusive rights to a licensee located in the target foreign country to use the intellectual property for a defined purpose for a certain period of time as agreed to by both parties in the contract (Aulakh, Jiang, & Li, 2013: 700).

In other words, licensing describes contractual transactions in which the owner of knowledge-based resource assets sells to another organization or individual the right to use these intangible resources for a defined purpose. Under the licensing arrangement, the licensor transfers, but does not give up, this ownership of the knowledge in exchange for the payment of royalties by the licensee (Luostarinen & Welch, 1997: 31–32). The royalty to the licensor, agreed to and documented in the contract, is normally calculated and paid based on each product unit sold by the licensee. License agreements offer the advantage to the licensee of gaining access to advanced, but legally protected, intellectual knowledge. The licensee takes the entrepreneurial risk and undertakes financial investments in facilities for material procurement, manufacturing, marketing, sales, and distribution of the products and services in the target foreign markets where the licensed knowledge is used (compare Figure 45).

Licensing can be attractive for rather small firms that have limited financial resources because it allows them to build up operations outside their home country. Furthermore, licensing as an international market entry mode is desirable in industries characterized by relatively short product and technology life cycles, such as high-technology industries.