1How to Combine Theory and Business Practice?

1.1About Theory

‘There is nothing more practical than a good theory,’ wrote Lewin (1952: 169). In other words, theorists should develop new ideas for understanding and conceptualizing a challenging research issue, ideas that may suggest potentially fruitful and practical avenues for dealing with the issue in the real world (Vansteenkiste & Sheldon, 2006: 63).

Wacker (2008: 7) describes a theory as a set of conceptual relationships that mainly comprises four properties: definitions, domain, relationships, and predictions. The first property, ‘definitions’, refers to a clear terminology and description of the target subject. ‘Domain’ means that a good theory provides generalizations and abstractions of the phenomena observed in reality. The third property, ‘relationships’, focusses on the consistency of the entire theory and the possibility of verification of the variables in the theory. Finally, a well-grounded theory allows valuable ’predictions’ for the future (Wacker, 2008: 7–8).

Eisenhardt (1989: 532) defines the development of theory as a central activity in organizational research. Theory is developed by combining observations from literature, common sense, and experience. The goal of explanatory (academic) research, including inductive theory building and hypothetical deductive theory testing, is to develop an understanding of an existing phenomenon as well as to develop theoretical explanations for and predictions regarding the phenomenon (Holmström, Ketokivi, & Hameri, 2009: 68–69).

There are concerns that academic research findings are, to some extent, not useful for business practitioners because a theory necessarily reduces the multifaceted and complex issues of a firm’s environment to a generalized and simplified model. Thus, a theory provides only limited potential for specific recommendations to managers. The gap between theory and practice is known as the knowledge transfer problem. Knowledge transfer is based on the assumption that practical knowledge (knowledge of how to do things) in a professional domain is derived, at least in part, from research knowledge (knowledge from science and scholarship) (Van de Ven & Johnson, 2006: 802). It is necessary to reconcile theory building and business practice, with the aim of generating theory and academic research findings that are relevant and applicable in practice (Anderson, Herriot, & Hodgkinson, 2001: 392; Slack, Lewis, & Bates, 2004: 385). Research should conceptualize and generalize new developments of use to business practitioners, while, simultaneously, new knowledge derived from practice should stimulate new directions for research and theorizing (operationalizing theory). Van de Ven (2011: 44) proposes a ‘diamond model’ to link theory with reality, which suggests a process of

- –problem formulation, in which the phenomenon is grounded on concrete details;

- –development and testing of alternative models to address the research question;

- –collection of evidence that allows comparing existing alternative models; and

- –communication and application of the findings in ways that encourage their use in the real world, for example in business practice.

Researchers should locate themselves in both the theoretical and the practical perspectives in the research cycle at different times. They cannot stay fixed in either the world of practice or the world of theory. Researchers should keep in mind Poole and Van de Ven (1989: 562), who argue that ‘even a good theory’ is a limited and ‘fairly precise picture’ as it attempts ‘to capture a multifaceted reality with a finite, internally inconsistent statement’ and is, therefore, essentially incomplete. Thus, the challenge addressed by international business and management research is to profoundly develop an interaction between the world of practice and the world of theory, rather than focussing on either one of them alone (Tranfield & Starkey, 1998: 353).

1.2Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Research Methods

Qualitative and quantitative research methods have in common that researchers systematically collect and analyze empirical data and carefully examine the patterns in it. However, the two approaches differ in some ways that mainly depend on the research subject and the availability of reliable information and data. Qualitative research methods describe and interpret a research object if a reasonable amount of quantifiable data is not available and, therefore, hypothesis testing is impossible. The main circumstances in which qualitative research approaches are recommended are, for example, when the research subject

- –is new and, therefore, reliable data sets in larger numbers are not available yet;

- –tends to be complex and needs to be described in depth;

- –is based on variables that are difficult to quantify; and

- –requires an analysis aimed at formulating specific recommendations instead of deducing general models.

Because qualitative research is usually done in exploratory settings, that is, in studying topics that are new to the field and hitherto under researched, it is of vital importance to make sure the subject matter is truly novel and merits attention (Birkinshaw, Brannen, & Tung, 2011: 579).

The qualitative researcher views the social phenomena of complex social networks holistically (Orum, Feagin, & Sjoberg, 1991: 6–7). This explains why qualitative research studies appear as broad, with panoramic views of an object, rather than as a micro-analysis. The more complex, interactive, and encompassing the narrative, the more desirable qualitative study approaches are. Qualitative researchers often rely on interpretative data and apply ‘logic in practice’ by following a nonlinear research path. ‘Logic in practice’ is based on an apprenticeship model and the sharing of implicit knowledge about practical concerns and specific experiences. The researchers speak a language of ‘cases and contexts’ (Creswell, 2009: 182; Neuman, 2006: 151).

In heuristic qualitative research, the data analysis tries to find similarities, which help with formulating propositions, research questions, and hypotheses, instead of simply testing a hypothesis, which is done at later stages of research when more information and datasets relevant to the target subjects are available (Kleining & Witt, 2001: 12). Qualitative research methods are particularly well suited to theory development, which means both framing a study in terms of the existing debates in the literature and being explicit about what body of theory(ies) it is building upon and why (Birkinshaw et al., 2011: 579).

In order to explain outcomes in particular cases, qualitative researchers think about the factors that may be causal related to a research subject. Thus, with this approach, scholars seek to identify the main variables (causes) and their combinations that influence the research phenomena (outcomes). The approach assumes that there are multiple causal paths (equifinality) to the same outcome. Research findings can be formally expressed through Boolean equations such as the following.

Outcome (Y) = Causing Variables A (t1, t2 … tn) and B (t1, t2 … tn) and C(t1, t2 … tn)

Because the causing variables (A and B and C) may change over time, it follows that the researcher must make a number of observations over time. This might involve a very long period of time (e.g., years, decades) or multiple observations taken over a short period (e.g., an hour, a week) of time (t1, t2 … tn). To say that A and B and C cause the outcome Y presumes that all other things are equal. In other words, any temporal variation in Y observable from t1 to tn should be the result of temporal variations in A and B and C (the causal factors of interest). This ceteris paribus assumption must hold; otherwise, causal argumentation within a qualitative research project, such as a case study, is impossible (Gerring & McDermott, 2007: 690).

In order to figure out critical A and B and C variables, for example in a field study with interviews of experts, semi-structured questionnaires that include ‘open questions’ and ‘closed questions’ are often recommended. Open questions aim to elicit a free flow of thoughts and storytelling by the interviewee. ‘Closed questions’ are aimed at ranking the interviewees’ answers, usually in a ‘Likert scale’, ranging , for example, from ‘strongly agree’ (+5) to ‘strongly disagree’ (‐5) (Baker, Thompson, & Mannion, 2006: 40). It is always very important ‘to leave the door open for the interviewee’: thus, to let her or him have the chance ‘to escape from answering’ by providing an option to indicate that the interviewee does not know or chooses not to answer; for example titled ‘I have no opinion / I don’t want to answer ’etc. This neutral value box avoids that the research outcomes are biased because the interviewee feels forced to answer in a certain category (e.g. interviewee does not have the appropriate knowledge or feels uncomfortable to clearly positioning its opinion in the Likert scale, for what reason ever).

Various kinds of information sources, including media, annual company reports, industry surveys, and others should be explored to gather ideas about the relevant opinions and practices of the interviewee to guide the development of the interview questions. Prior to conducting the interview phase of the study, a pre-study period should be scheduled, where the researcher should hold mock interviews and fine-tune the research design and the interview questions (Wahyuni, 2012: 74).

Quantitative research, in which the analyst typically seeks to identify the values of variables and figure out the standardized relationships among them, differs from qualitative study (Mahoney & Goertz, 2006: 232). Quantitative research necessarily assumes that standardized and reliable data in larger quantities are available for statistical testing. In consequence, quantitative researchers apply ‘reconstruction logic’ and follow a linear standardized research path. ‘Reconstruction logic’ is based on reorganizing, standardizing, and codifying research knowledge, using explicit rules, formal procedures, and research techniques. Quantitative scientists tend to speak a language of ‘variables and hypotheses’ and emphasize measuring linked variables precisely and arriving at general causal explanations (Neuman, 2006: 151).

Thus, the vital requirement for hypothesis formulation in the course of conducting quantitative research is that reliable datasets in appropriate numbers are available. These data are collected either from secondary or primary sources or both of them. The main aim of quantitative research is hypothesis testing (null-hypothesis versus alternative hypothesis), which is carried out through analysis of the relationships among model-relevant variables. Therefore, quantitative research methods are particularly suitable for testing the validity of a theory and further development of a theory. Common statistical methods of quantitative research are located within the field of descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, mean, median, analysis of correlations among variables) and inferential statistics (t-test, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), regression analysis, etc.) (compare: Brosius, 2013; Schendra, 2008). Based on the discussion above, Figure 1 provides a comparative overview of the strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research methods.

Mixed research methods, as the term indicates, combine both qualitative and quantitative forms of analysis. Instead of simply incorporating both methods, mixed research approaches are rather applied in tandem in order to maximize research outcomes (Creswell, 2009: 4). The tandem approach alleviates the conceptual weaknesses of using only qualitative approaches (e.g., limited generalization of study outcomes) or only quantitative approaches (e.g., less in-depth understanding of the research phenomena). Combining qualitative and quantitative methods supports the identification of causal variables and the interpretation of the results (qualitative methods). On the other hand, statistical analysis (quantitative methods), such as frequencies and correlations among crucial variables, contributes to the ability to generalize research outcomes (Dobrovolny & Fuentes, 2008: 10). For decision makers in policy, business, and management, study outcomes from mixed research approaches are more useful if they provide quantifiable information about effects but also about the variables’ causation mechanisms that lead to certain effects (Obermann, Scheppe, & Glazinski, 2013: 255).

1.3Cases Studies: Why, How, and What?

Case studies, which were initiated and developed at the Harvard Business School during the 1920s, are a useful tool for research and teaching that provide a transition between theory and practice. Formal case study structure includes identification of a problem, development of initial research questions, and conducting research by collecting information and making observations. Like other research approaches, there are methodological drawbacks: case studies do not deliver evidence about the perfect solution to an existing problem. The vital strength of case studies is that they connect students, scholars, and researchers to social phenomena and real-life situations in a way that helps to develop solution scenarios and, as a result, sharpen complex thinking and decision-making behavior (Breslin & Buchanan, 2008: 36–38).

Case studies are generally described as useful for theory development (Aaboen, Dubios, & Lind, 2012: 236) because they are exploratory and descriptive by nature, identifying a new and often complex research phenomenon (Breslin & Buchanan, 2008: 38). A case study serves as a research strategy that examines, through the use of a variety of data sources, an event or subject in its naturalistic context, with the purpose of confronting theory with the real world (Piekkari, Welch, & Paavilainen, 2009: 569). Yin (2014: 16) describes case studies as an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between the phenomenon and the context of research are not clearly evident. Built on a profound and solid literature review, a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence with various variables of interest and data including archival data, annual reports, market survey data, statistics, press releases, interviews, and observations (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007: 27–28). A case study approach can also be used to demonstrate whether a theory is applicable or rather lacks applicability under certain conditions not previously investigated. Thus, a case study can impose restrictions on a theory’s generalizability or can lead to totally disproving a theory. In addition, a case study can provide ‘a high degree of control for testing a new theory or comparing multiple competing theories’ (Dowlatshahi, 2010: 1365).

It is of vital importance that the research questions guide the choice of methods and not vice versa. The researcher should clearly articulate in his or her paper why a particular qualitative or quantitative method or a combination of methods is appropriate for the objectives of the study (Birkinshaw et al., 2011: 579). Defining the research questions serves as the most important step to be taken in a research project.

‘Why’ and ‘how’ research questions are posed by the researcher because such questions are more explanatory and can better analyze complex dynamics in real-context reality. Thus, ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions are likely to lead to the use of a case study or experiment as the preferred research method. These questions deal with the operational links and relational causalities of variables, which need to be traced over time, rather than mere frequency observations (Yin, 2014: 10). Van de Ven and Engleman (2004: 355) claim that ‘how’ questions describe and explain temporal sequences of events studied over time.

Yin (2014: 10) distinguishes between two types of ‘what questions’. There is a category of ‘what’ questions that is exploratory, where the goal is to develop pertinent hypotheses and propositions for further inquiry. The use of an exploratory case study applying ‘what’ questions should include the following steps (Dowlatshahi, 2010: 1369–1370):

(1)review of existing academic and practitioner literature;

(2)identification of critical cause-and-effect variables for the case study subject;

(3)development of propositions and hypotheses; and

(4)statement of the insights gained as a result of evaluating the propositions and developing and presenting the case study.

Another category of ‘what’ questions, similar to ‘who’ and ‘where’ questions (or their derivatives ‘how many’ and ‘how much’), utilizes survey methods of analysis or the analysis of archival data. These survey methods are advantageous when the research goal is to describe the incidence or prevalence of a research phenomenon or when research outcomes are predictive (Yin, 2014: 10).

In case studies where the research subject might be one firm (single case study) or several firms studied, for example, in the course of an industry analysis (multiple case studies), the researcher explores crucial events, activities, or processes through in-depth analysis. Single firm case studies are developed to identify benchmarks within an industry (e.g., market size leader) or special and unique cases (e.g., technological innovators) or to figure out which firms are the worst performing in order to learn from their mistakes. Multiple cases are discrete experiments. Based on a replication logic, multiple case studies contrast and extend knowledge to develop the emerging theory, and this approach takes into account the real-world context in which the research phenomena occur (Eisenhardt, 1989: 534; Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007: 25). While single case studies provide a description of an existing single phenomenon (Siggelkow, 2007: 20), multiple case studies naturally provide a stronger ground for theory building and thus yield more robust, sustainable, and reliable information. The larger the multiple case study sample, the better the prerequisites for finding common cause-and-effect relationships, which leads to a higher degree of generalizability of the research outcomes.

Case study research results are incrementally developed over a period of time. The methods for analysis progress through research phases (Atteslander, 2003: 84–85). When case study research is undertaken, the scientist uses complex reasoning that is multifaceted and iterative and considers various aspects simultaneously. Although the reasoning is largely inductive, both inductive and deductive processes are at work. The thinking process is also iterative, with a cycling back and forth from data collection and analysis to problem reformulation. Added to this are simultaneous activities of collecting and analyzing information and writing up the ‘case story’. The research process should be flexible and open to new or even unexpected pragmatic information that reflects the observed reality (Creswell, 2009: 182–183).

The analyst emphasizes conducting detailed examinations of cases that arise in the natural flow of real life, trying to present authentic interpretations that are sensitive to specific social-historical contexts. The passage of time, which may involve years or decades, is integral to case studies. Analysts look at the sequence of events and pay attention to what happened first, second, third, and so on. Because qualitative researchers examine the same case or set of cases over time, they can see an issue evolve, a conflict or solution emerge, or a social relationship or network develop. The researcher can detect processes and causal relations (Neuman, 2006: 151). Actual information sources for developing a case study, whether available in hard-copy, electronic version, or transcript from interviews are listed below.

(1)Academic literature

–books, journals, conference proceedings, etc.

(2)Secondary company and industry sources

–company annual reports, balance sheets, press releases, etc.

–official statistics, (e.g., International Monetary Fund (IMF), Eurostatistics, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), United Nations (UN), etc.)

–data provided by commercial market research institutions (e.g., DisplaySearch)

(3)Primary study information sources

–face-to-face interviews or electronic or phone interviews (e.g., questionnaire results, minutes of meetings)

Researchers should be reflective in their use of the case study and more precisely specify the type of case study they are conducting: for example, whether their study targets a best case (e.g., industry benchmark) or worst case, whether a single case study or an interview-based multiple case study is utilized, and so on (Piekkari et al., 2009: 584).Welch et al. (2011: 744) propose a ‘case study memo’,which helps to systematically figure out the linguistic elements of a case study as well as provide explanations of the researcher’s theorizing process and corresponding assumptions. Having the questions listed below in mind is very useful not only when reading and evaluating case study articles found in the academic literature but also when writing about one’s own case study.

- –Does the case study article state the theoretical objectives and relevant research questions?

- –How are the theory and empirical data related and mutually integrated?

- –Is the research methodology properly explained and which information sources are used?

- –Are the case outcomes generalizable for theory development?

- –Do the case outcomes allow causal claims for the research phenomena (Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki, & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, 2011: 744)?

- –Are there implications for management and business executives?

- –Are there proposals for future research in order to overcome current research gaps?

Like other research approaches, case study methods come along with drawbacks. First of all, no matter how large the sample is, researchers collect detailed information using a variety of data collection approaches and techniques; nevertheless, the outcomes still have the risk of being interpreted subjectively by the researcher (Creswell, 2009: 15). Reasons for subjective interpretation are, on the one hand, that the researcher, no matter how carefully the research is done, has an outsider perspective. Therefore, the researcher should have, on the other hand, some profound understanding of the subject of the case study, such as knowledge of the firm or the industry. The overwhelming advantage of case studies is that they provide authoritative, real-life business information. The specific case studies to be discussed in the following chapters of this book are used to combine and illuminate internationalization theories and market entry strategies and are designed to best serve the reader. The focus on Asian firms delivers interesting insights into modern high-technology industries and changing global business dynamics. Let us start with the first case study regarding Panasonic (Japan) in the following section.

Chapter review questions

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of qualitative and quantitative research methods?

- What research goals are served by why, how, and what questions?

- Develop a draft of a single case study that aims to clarify a firm’s international market entry strategies. (You can select the target firm.)

1.4The Case Study of Panasonic: Do You Believe in its Future Business?

1.4.1Company background

In 1918, Konosuke Matsushita established the company known as Matsushita Electric Housewares Manufacturing Works, which was changed to Matsushita Electric Manufacturing Works in 1929. The company has been using the name Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd., ever since its incorporation as a joint stock corporation in 1935. While it had used the National and Panasonic brand names over a long period, the Japanese management decided in 2003 to unify its global brand to Panasonic with the brand slogan ’Panasonic ideas for life’. Since October 1, 2008, the company has officially been named Panasonic Corporation (Panasonic, 2008).

Immediately after founding the company, Matsushita began production of an innovative attachment plug and a two-way socket, both of which he designed himself. These new products became very popular, earning the company a reputation for high quality at low prices. Matsushita Electric began printing English instructions for its products in 1931; and in April 1932, Konosuke Matsushita set up an export trading department to carry out research and marketing development in order to evaluate the company’s international sales potential. This represented an innovative step in an industry where, in Japan, exports were traditionally left to large trading houses. With a unified policy for domestic and export markets, the company was able to actively expand its export business. With exports increasing, Konosuke Matsushita incorporated the export trading department as the Matsushita Electric Trading Company in August of 1935. In 1936, the founding owner sent three people to the US and Europe in order to learn about advanced industries there. They visited about twenty local factories, including Philips and Siemens (Matsushita, 2008).

In 1952, after intense negotiations, Matsushita Electric concluded a technical and capital cooperation agreement with Philips of the Netherlands, setting up Matsushita Electronics Corporation as an international joint venture. This was the result of Konosuke Matsushita’s efforts to find an overseas business partner, convinced that the adoption of advanced Western technology was essential for Japan’s post-war reconstruction. In 1954, Matsushita Electric allied with Victor Company of Japan (JVC), a record player producer that was established in 1927 by the Victor Talking Machine Co. of the United States. In 1959, ready to expand business activities abroad, Konosuke Matsushita founded Matsushita Electric Corporation of America in New York as its first overseas sales company. He urged his managers to adapt to their new host nation and to apply themselves to providing products that Americans would appreciate. The formation of an overseas sales network proceeded at a rapid pace.

The first European sales company established was National Panasonic GmbH in West Germany in 1962, which was used as a base to enter the European market. Since then, various sales companies have been established throughout the world. On March 22, 1974, Motorola Inc. of the US and Matsushita Electric of Japan signed a contract for the purchase of Motorola’s television set operations in the US and Canada. The purpose of the acquisition was to start a television business in the US market. On May 22, 1987, Matsushita Electric and Beijing City in the People’s Republic of China signed an agreement to establish an international joint venture to produce cathode ray tubes (CRTs) for color TVs. This was Matsushita Electric’s first investment in China in the post-war period. The new company, Beijing Matsushita Color CRT Co., Ltd., started production in June 1989 with about 1,400 employees. The company first produced 21-inch color picture tubes and later added 14-inch and 18-inch tubes. The products were supplied to color television set plants in China (Matsushita, 2008).

MCA Inc. joined the Matsushita Group in November 1990. MCA was a multibillion dollar diversified international entertainment conglomerate engaged in the production and distribution of theatrical, television, and home video products, as well as the operation of two amusement parks in Hollywood, California, and Orlando, Florida. MCA brought a diversity of new capabilities into the Matsushita Group and also the promise of innovation in the field of electronic entertainment through the integration of hardware and software products. However, in June 1995, Matsushita Electric divested its engagement in business fields diversified from consumer electronics and transferred an 80 percent share of equities in MCA Inc. to the Seagram Company Ltd., a Canadian liquor manufacturer (Matsushita, 2008).

In the television set business, Matsushita concentrated its research and development resources during the 1990s on the development of the plasma technology. In 1996, Matsushita developed the world’s first 26-inch plasma television set. In the field of plasma displays, the Japanese electronics firm was technologically ahead of its time. Would this be worthwhile in the future?

1.4.2The market at the beginning of the 21st century

In 2001, as the market for plasma television set panels was expected to grow significantly and Matsushita Plasma Display Co., Ltd., began full-scale mass production of modules targeting high picture quality at an affordable price, Matsushita aimed to be the number one plasma display panel manufacturer in the industry by strengthening its manufacturing structure, including the commencement of production at its plant in China in December 2001 (Matsushita, 2002).

Also in 2001, Matsushita centralized its domestic manufacturing locations, having discontinued monitor tube production and implemented the joint global supply and purchase of television sets. As a pacesetter in the digital television set industry, Matsushita led the market in televisions with digital satellite tuners. In 2002, the company extended its line-up of flat-surface cathode ray tube television sets and augmented its plasma display panel product portfolio with new 36-inch and 42-inch models, followed by a new 50-inch television set model, all with the industry’s highest levels of brightness and contrast to date and all equipped with digital satellite tuners. As a result of the upcoming flat-panel technologies, which resulted in a continued decline of the cathode ray tube television set business, Matsushita decided to reduce cathode ray tube production incrementally, which ended in the closure of all remaining cathode ray tube related operations worldwide beginning in 2006 (Matsushita, 2005).

In April 2002, Matsushita established eP Corporation, a common joint venture with Toshiba Corporation and Hitachi Ltd., which launched the world’s first trial service integrating digital broadcasting and high-storage data casting. The introduction of this service enabled users in Japan to access multiple channels with advanced functions on demand as well as to participate in home shopping, home banking, and other interactive services (Matsushita, 2002). However, customers who have an affinity for using interactive services can use their Internet-linked computer and do not necessarily need a television set. Thus, the ambitious plans to create new markets for television sets with compatible terminals could not be realized as expected.

The decline of the conventional cathode ray tube business, which came along with an increasing cost pressure in flat-panel technologies, semiconductors, and other electronic components, caused a severe loss for Matsushita in 2002. Its efforts to reduce fixed costs and rationalize activities in parts and material purchasing were not enough to offset negative factors stemming from the price decline. Furthermore, the company incurred various restructuring charges, which included USD 1.23 billion related to employment reorganization programs, USD 1.35 billion for impairment losses associated with the closure or integration of several manufacturing locations, and a write-down of investment securities, resulting in a net loss of USD 3.24 billion (Matsushita, 2002). In terms of sales and net income, Matsushita recovered stepwise after 2002 and successfully managed a turnaround. The restructuring activities of 2002 resulted in an increasing profit.

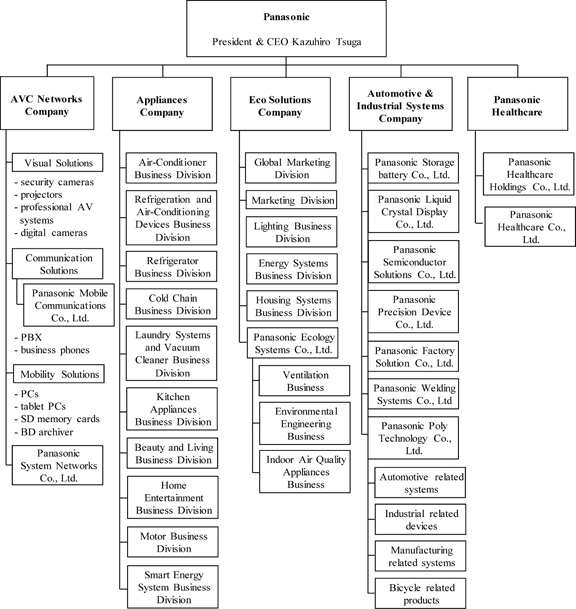

The revised organization that Matsushita launched in 2002 as a result of its restructuring program was modified over the years. The organization was divided into five major business divisions. The first line of business is named AVC Networks Company and contains, for example, digital cameras, mobile communication, projectors, and data storage devices. Products such as air conditioners, laundry systems, vacuum cleaners, kitchen equipment, and home entertainment are housed in Appliances Company. Recently, new business fields, such as Eco Solutions (e.g., energy systems, lightning), Automotive & Industrial System Company (e.g., liquid crystal display, battery, automotive related systems), and Panasonic Healthcare were launched (compare Figure 2).

1.4.3What comes next?

Mainly because of the initiative of Matsushita, which concentrated on plasma panel technology but aimed to manufacture and sell liquid crystal display (LCD) panels for flat-panel TVs, IPS Alpha Technology started operation in 2005 against an industry background of increasing international demand for LCD TVs. TV manufacturers faced a growing necessity to ensure a stable supply of high-quality panels at reasonable prices. Thus, Panasonic, Toshiba, and Hitachi decided to join forces to enable themselves to effectively respond to production price pressures and rising customer expectations for high-definition picture quality. Because the IPS Alpha joint venture incorporated Hitachi Displays’ world-leading In-Plane-Switching (IPS) mode system technology, the three partner companies enjoyed favorable conditions for gaining highly competitive market positions based on standardization and high capital-efficient mass production of IPS mode LCD panels (Hitachi, 2008; HitachiDisplays, 2004). In June 2010, IPS Alpha Technology finally became a full-fledged wholly owned subsidiary of Panasonic Corporation. Beginning on October 1, 2010, the subsidiary company was named Panasonic Liquid Crystal Display Co., Ltd (Panasonic, 2010).

Figure 2. Organization (status 2015) of Panasonic Group (Panasonic, 2011, 2013, 2015a)

The incremental turnover of the joint venture majority by Panasonic was due to the fact that the global LCD business had developed greatly since 2006. This market attractiveness meant that existing and new competitors from Japan, South Korea, China, and Taiwan sharply increased their capacities during that time. In 2009, Panasonic reached a net income of USD 4.3 billion, which represented the highest profit ever during the period from 2006 to 2014 as the following figure illustrates (Panasonic, 2011, 2013, 2015a).

What happened in the ups and downs of the following years is rather similar to a roller coaster ride. In 2010, Panasonic profits turned into losses (USD 2.06 billion), while in 2011, the firm came back to USD 1.032 billion in profits. A year later, the largest Japanese electronics firm Panasonic reported a loss of USD 8.7 billion – the biggest in the company’s ninety-five-year history. At the same time, net sales declined as well. The primary causes of this were, according to Panasonic, the global economic slowdown and instability in the financial markets due to the European debt crisis as well as the extensive supply chain disruption caused by the flooding in Thailand that occurred in October 2011. Sales of flat-panel TVs and mobile phones plummeted in the period, although sales of PCs and some home appliances enjoyed a small boost. Panasonic moved to shake up its business following the purchase of Sanyo Electronics, including revamping its TV and chip operation and cutting jobs (Halliday, 2012).

Figure 3. Net sales and net income of Panasonic Group for the period 2006 to 2014. Developed based on various firm related sources (Panasonic, 2011, 2013, 2015a)

For too long a time, the Japanese firm focussed its research and development efforts on plasma displays, which the management thought would become the leading display technology. However, liquid crystal display (LCD) panel technology assemblers like Sharp and Samsung improved their display performance significantly in terms of picture, brightness, sharpness, energy consumption, and viewing angle, which meant that it became increasingly difficult for Panasonic to be competitive. In 2013, Panasonic announced that production of new plasma units would end in December; and all related operations would be wrapped up by March 2014. Three of Panasonic’s factories stopped building new units. In the press release, Panasonic said that due to rapid, drastic changes in the business environment that led to increasing supply, which caused price pressure from more affordable LCD TVs, the ‘unhappy decision had to be made’. As for the future, Panasonic communicated that plasma research and development efforts would likely be diverted to OLED. The company sees televisions using the OLED technology as one of the key future products, and it is working to insure that it can make affordable OLED TVs that still leave room for profit before putting any up for sale. If and when that day comes, sticklers for the picture quality offered by plasmas should be more than happy with OLEDs (Savov, 2013).

At the all-time height of its losses in 2012, electric car manufacturer Tesla Motors and Panasonic announced that together they would develop nickel-based lithiumion battery cells for electric vehicles. Panasonic had been rumored for months to be a battery cell supplier (Garthwaite, 2010). And three years later, Panasonic’s chairman and CEO, Joe Taylor, said at the 2015 Consumer Electronics Show that he expects Tesla to produce 500,000 electric vehicles by 2020, with the help of the so-called Gigafactory, a USD 5 billion production facility. The Giga Factory is a massive production plant Tesla and Panasonic are building together in the state of Nevada. It will primarily serve to produce lithium-ion batteries for Tesla’s cars at a lower cost. Panasonic jointly builds the battery cells used in the Model S and has promised to invest ‘tens of billions of yen’ (hundreds of millions of dollars) in the plant. The cost of batteries has often been cited as the biggest hurdle Tesla faces in growing its footprint. With the new Gigafactory, Tesla expects to lower the cost of battery production by nearly 30 percent. The Gigafactory, scheduled to open in 2017, is planning to hire more than 6,500 people and will cover 10 million square feet (Kim, 2015).

Panasonic is also expanding its Automotive & Industrial Systems Company, which is an in-house company of Panasonic Corporation that operates a B2B solutions business on a global scale. The business covers in-car infotainment-related equipment, in-car electronics, batteries, electronic devices, semiconductors, manufacturing-related systems, and so on. With a focus on the automotive and industrial fields, Panasonic intends to work to enhance customer value through the provision of solutions in a wide range of fields, from devices to systems.

‘We also strive to leverage our collective capabilities to achieve the Panasonic vision: A Better Life, A Better World’ (Panasonic, 2015b).

Chapter review questions

- Before reading the case study, which products did you mainly link with the Panasonic brand? Did you change your opinion after reading the case study?

- Suppose you are in the shoes of Panasonic’s management. Which businesses would you further develop for the future? Please provide reasonable arguments to explain your answer.