However, the more the franchisee is monitored and controlled by the franchisor, the more questionable becomes the entrepreneurial freedom of the franchisee, which is usually claimed as one of the driving advantages when promoting franchise concepts. Because of the franchise start-up fee – which can easily reach, conditional to the business concept, more than one hundred thousand Euros – the dependency of the franchisee on the franchisor seems to be incomparably higher than vice versa from the franchisor’s perspective. Thus, as in all contractual relationships, the right selection of a partner, which includes the careful evaluation of the business concept, is of vital importance for the involved parties.

3.3.1.5Management contracts

Management contracts offer a means through which a firm may use some of its personnel to assist a firm located in a target foreign country for a specified fee and period of time (Wheelen & Hunger, 2010: 262). The management (knowledge) transfer recipient is seeking a contractual partner that is able to run its enterprise and, in parallel, qualifies and trains its staff by providing technical, commercial, and managerial knowledge. At the same time, the transferring firm enters new foreign markets, selling its managerial expertise and bringing in resources that help to improve the competitive positioning of the contract partner abroad, who in return pays fees for the consulting service (compare Figure 47). Through contractual relations with local governments, the firm is able to enter potential foreign markets where the local authorities may have a less than open attitude towards foreign investors (Foscht & Podmenik, 2005: 582–583).

While training the staff, including transfer of managerial and technological knowhow, there is a risk for the CMP that a new competitor is being fostered and developed. In addition, the management supplying firm needs to send qualified personnel, particularly those with cultural sensitivity and language skills. Such a qualified pool of employees is not always readily available. Personal and cultural conflict with locals may arise, depending on the expatriate’s characteristics and qualifications for carrying out the contract tasks. Opposing expectations regarding between the contracting firm and the local governments may also provide the basis for conflicts. The local management may have divergent work ethics or show a less motivated learning behavior. Nevertheless, management contracts can be an interesting and profitable market entry mode. In order to successfully realize management contract projects, considerable effort needs to be made in terms of communication at the local level as well as back at the CMP headquarters (Luostarinen & Welch, 1997: 105).

3.3.1.6Turnkey contracts

Turnkey describes a market entry mode where a firm sells complete operations and supply and distribution chain services: material procurement, assembly, testing, and aftersales service, including warranty support (Henning, 2013: 18). Turnkey operations are usually used in large investment initiatives, such as the design, planning, construction, and building of a large manufacturing plant in a target foreign country. Market entry through turnkey usually includes the start-up of operations as well as necessary training, qualification, and consulting with the local personnel. The firm then ‘turns the key over’ to the local government in return for an agreed upon payment of use fee (Deresky, 2014: 218). Turnkey operations are attractive for firms that have, for example, specific engineering and complex technological process know-how.

The build, operate, transfer (BOT) concept is a variation of the turnkey operation. Instead of turning the facility (e.g., power plant or toll road) over to the host country when completed, the firm operates the facility for a fixed period of time. During this operating period, the company earns back the investment, plus a profit. At the end of the time period agreed upon with the foreign contract partner, the firm turns the facility over to the contract partner – for example, the local government at little or no cost to the host country (Naisbitt, 1996: 143; Wheelen & Hunger, 2010: 262).

Critical success factors for the turnkey selling firm usually derive from the availability of qualified personnel; a less developed infrastructure; security issues; and limited availability of local suppliers, logistics, and other service firm networks. There may also be a particular risk exposure if the turnkey contract is with the local government of the target foreign country, which is often the case in politically and economically rather fragile countries. The firm may face the threat of contract revocation initiated by the government if differences of opinion related to the project aims and targets arise between the contract partners, which may occur over time (Deresky, 2014: 218).

3.3.2Cooperative modes of market entry

3.3.2.1Strategic alliances

Strategic alliances, which belong to the category of cooperative market entry strategies, are formal mechanisms that are established to strengthen the participating firms’ competitive positions in the markets. International strategic alliances are working partnerships between firms across national boundaries in the same or different industries. Strategic alliances are agreements between two or more participating organizations that target business objectives that are rather long term (Deresky, 2014: 235). The firm members usually have access to strategically relevant resources, such as client data and distribution channels that are shared between the alliance partners. While vertical strategic alliances display cooperation between suppliers and buyers, horizontal strategic alliances are characterized by cooperation at the same stage of value-added activities. Lateral alliances entail the firms’ cooperative sharing of products and services originating in different lines of business (Welge & Holtbrügge, 2015: 118).

Firms agree on cooperative strategies with other industry stakeholders – such as competitors, suppliers, and customers – for various strategic purposes. Firstly, an international strategic alliance may facilitate entry into a foreign market because of the regional expertise and market goodwill of the local firm. The local firm may help secure government and public approval to establish the business. Market entry activities tend to be more efficient because the foreign firm supports entry with its regional marketing expertise and better information access to behavioral aspects, such as purchase attitudes, service expectations, and design tastes of the customers. An alliance, supposing it runs well, is a way to bring together complementary knowledge, such as regional client data, that neither company could easily develop on its own.

Firms seek to establish strategic alliances in order to implement different product branding strategies in the international markets. These strategies include direct extension of an existing brand to the new product, introducing a new brand for a new product, and collaborating with a local brand (of the partner firm) to establish a brand alliance for a new product (Li & He, 2013: 90). For example, Sharp is well known for innovative and quality products in Asia. However, the Japanese firm had been confronted with rather weak brand recognition in Europe. Therefore, in 2002, Sharp’s management decided to establish a strategic alliance through capital participation of 8.9 percent with the reputable German Loewe AG. Sharp delivered its innovative liquid crystal display modules, which were assembled and sold by Loewe in the Western markets at much higher prices than Sharp could have reached (Sharp, 2004).

In various markets such as high-technology industries, particularly at the beginning of a new technology life cycle, firms have to decide on common technological or industry standards. At this stage, the firm’s management often agrees on strategic alliances in order to implement their favored technological standards for the future. An alliance of companies can look forward to promising earnings due to the fact that the defeated alliances of firms, in terms of another competing technological standard, usually have to license the superior technology. For example in 1979, Philips joined its research and development efforts with Sony for the standardized development and introduction of the ‘world audio disc’. The cooperation between Philips and Sony was continued in 1992 (joint development of a DVD industry standard). However, the Sony and Philips partnership finally failed against the high-definition DVD standard of the rival alliance of Toshiba, Hitachi, Pioneer, JVC, Thomson, and Mitsubishi Electric. Panasonic, which supported Sony at the beginning, later joined the rival alliance in the technological battle. In 2008, the alliance group initiator, Sony, with its Blu-ray Disc™ won the competition against its Japanese rival, Toshiba, which was previously the leading firm in developing the high-definition DVD standard (Sony, 2008; WeltOnline, 2008). Just one year later in 2009, Panasonic, Philips, and Sony established, with other Blu-ray Disc™ patent holders, a license that covers essential patents for Blu-ray Disc™. The fees for the new product licenses are US $9.50 for a Blu-ray Disc™ player and US$14.00 for a Blu-ray Disc™ recorder. The per disc license fees for Blu-ray Disc™ will be US$0.11 for a read only disc, US $0.12 for a recordable disc, and US$0.15 for a rewritable disc (one-blue, 2009).

The formal difference, compared to a joint venture, is that a strategic alliance does not come along with a legally independent entity. All firms participating in a strategic alliance remain legally fully responsible for their business. In most cases, a strategic alliance is established as non-equity cooperation, meaning that the partners do not commit mutual financial investments (Hollensen, 2014: 379). However, there are also cases where firms decide to establish a strategic alliance in which one partner acquires a stake in the other partner or where both partners mutually hold equity participations. If the alliance partner is located in a target foreign market, the equity participating firm undertakes a foreign direct investment. Figure 48 illustrates the decisional alternatives of cooperative strategies, distinguishing between strategic alliances and joint ventures and corresponding relevant facets.

Potential disadvantages from alliance agreements derive from the risk of resource transfer, such as client data, marketing, and technological and managerial knowledge, to the partner firm, which is often, but not necessarily, a competitor. The right partner selection is of vital importance to the success of the alliance. A suitable partner should not exploit the alliance for its own needs. For example, it should not expropriate human resources, such as recruiting highly qualified alliance partner staff through attractive job offers in order to employ them in its own firm. The partner selection process plays a crucial role and includes the collection and analysis of publicly available information regarding potential partners as well as opinions, if available, from other industry stakeholders, such as logistic firms, suppliers, and customers (Hill, 2012: 507).

Against the background of liberalized market structures and the strategic importance of efficient resource allocation and global product launch speed, firms increasingly tend to agree on alliances (Inkpen & Ramaswamy, 2006: 88–89). For sure, the building of a successful alliance partnership belongs to the most complex of management tasks. Synergy effects of the partner firms often are not performing as expected – as many firms involved in international alliances have experienced to their regret.

3.3.2.2International joint ventures

A joint venture is formed when two or more legally distinct firms decide to own and control a common business – for example, manufacturing and sales of a particular product or service. A joint venture indicates a legally independent entity. The controlling parties, also named joint venture parents, contribute assets and, depending on each party’s equity share, the revenue and risks (Rugman & Collinson, 2012: 260–261). An equal joint venture describes the constellation when each party contributes half of the amount of equity, thus sharing the managerial control, risk, and earnings. Majority joint ventures describe the constellation when a firm owns more than fifty percent share of the joint venture and, thus, secures control of strategic-managerial decisions and corresponding resource allocations (Hill, 2012: 507).

A joint venture can be formed between firms that run businesses in the same industry, indicating similar value-added activities (horizontal joint venture). Alternatively, a joint venture can be established between firms that are located at different stages of the industry value-added chain (vertical joint venture), such as a supplier-buyer cooperation. Conglomerate joint ventures describe a constellation when the cooperating firms join different lines of businesses (Kutschker & Schmid, 2006: 862).

An international joint venture (IJV) describes an arrangement where at least one parent organization is headquartered outside the venture’s country of operation or if the venture has a significant level of operations in more than just one country. Driven by the fundamental changes that have occurred during recent decades toward internationalization of markets and competition and the increasing costs and complexity of technological developments, IJVs have become an important mode for international market entry (Frayne & Geringer, 2000: 406). The donation and share of resources – such as technological and managerial knowledge, operational capacities, management expertise, and the mutual access of the supplier and customer networks – serve as important advantages for the partner firms.

An IJV can be formed in order to organize research and development and/or manufacturing facilities for the involved partners. This arrangement belongs to the category of an upstream-based partnership. When companies join their marketing, distribution, sales, and after-sales service network, this belongs to downstream-based collaborations. In the case where the joint venture partners have complementary competencies in the value chain (for instance, company A, technology, and company B, brand name), this is an upstream/downstream-based collaboration (Lorange & Roos, 1995: 333).

IJVs are often established under time pressure and fast-changing market environments. Consequently, the qualification development of the venture staff is usually done too quickly or does not take place at all. However, the proper preparation of the venture staff through adequate training programs is of vital importance for the venture lifetime. Cooperative market entry strategies through IJVs are not static constructs. The factor of time plays an important role for the partner firms, which unavoidably change their industry network position as the worldwide market circumstances continuously develop. The network repositioning process (in a positive or negative direction) often develops unnoticed or underestimated by the firms but, in turn, has a decisive influence on the IJV business success.

When a multinational firm’s strategic business unit performs less profitably than expected or accumulates losses, the top management has to decide whether to restructure or even shut down this poorly operating division. Instead of factory closures, there is the alternative of finding another partner with whom the firm can establish a joint venture, hoping that both parties can better manage operations and, thus, improve the business. The transfer of deficiently operating functions to a legally independent joint venture company is perceived less negatively by the public than factory shutdowns, which usually come along with the release of employees. In the course of transferring the business, both parties’ top management often emphasize the term ‘synergy effects’ as a result of the mutual resource commitment. However, synergy effects are often overestimated because both parties, before the joint venture is established, rather hide their individual weaknesses in order to secure a higher interest stake (‘Who wants to join with a poor performing partner?’).

There are several other reasons that firms decide to establish an IJV, such as entry into geographically new markets (Hollensen, 2014: 382). For example, firms notice that they lack the necessary market knowledge and brand recognition in the target foreign market. Rather than trying to develop these capabilities internally, the firm may identify another organization that possesses those desired marketing skills. Joint ventures may be helpful when entering a foreign market, particularly where socio-cultural or political-legal differences relative to the home country exist. Cooperation with a firm in the host country can increase the speed of market entry. The bundle of distribution channels increases sales capacity and allows access to geographically diverse markets. The costs of after-sales service may be reduced, and the service reaction time may be improved. Furthermore, some countries (e.g., India) try to restrict foreign ownership. Governments may create pressure on multinationals to establish international joint ventures with local firms.

Global operations in research and development and operations are expensive, but often necessary to achieve competitive advantages. Joint ventures allow participating firms to pool financial capital, human resources, research and development, and operational capacities to gain economies of scale because of joint use of their facilities, thereby reducing the costs per output unit. Pooling the procurement increases the bargaining power of the joint venture partners and better provides prerequisites for standardized platform manufacture. Joint ventures may also be used to build jointly on the technological expertise of two or more firms in developing products that are technologically beyond the capability and resources of the firms acting independently. Complementary technologies provided by the partners can lead to new product or manufacturing process developments. Joint research and development helps to accelerate product innovations (Hollensen, 2014: 379, 382).

Trust is most crucial to the success of an IJV. But how can it be developed? Choose a partner with compatible strategic goals and objectives, and work out with the partner how and to what extent proprietary technology and sensitive information is to be shared. Recognize that most IJVs usually last a couple of years and probably break up once a partner feels it has incorporated the skills and information it needs to go it alone (Deresky, 2014: 244).

When two firms first initiate a relationship and start to interact with each other, trust on both sides might only be present to a limited extent because trustworthy behavior first has to be proved to one another. When the first series of IJV resource transactions are successful and carried out to partners’ satisfaction, firms may be willing to increase the size of the resource and accept higher risks, which naturally correlate with greater benefits. This implies that firms gradually gain trust in the relationship when a series of resource exchange episodes within the IJV have been performed successfully. Likewise, it posits that an increase in trust enhances the partners’ willingness to increasingly commit to the exchange relationship. Shared values and mutual interests and IJV business objectives entail that both parties have a congruent vision of the direction in which they want to develop their relationship (Lambe, Wittmann, & Spekman, 2001: 11).

Joint ventures between Japanese firms follow a certain pattern that is characterized by the mutual wish over time to create a ‘win-win situation’. The long-term time horizon allows partner firms to build up mutual trust and helps to overcome the short-term venture difficulties that come up during the partnership. Experiences collected in one previous joint venture project improve organizational issues and the corresponding business performance of the next venture operation. Moreover, Japanese firms make sure the joint venture management does not operate separately and too independently. The management is integrated into the parent firm’s structure and long-term strategic plans. The long-term oriented business relations between Japanese firms mean that the partner firm relations are not interrupted when the venture project comes to an end. Instead, Japanese firms often cooperate on a number of common joint venture projects with one selected partner firm. If a joint venture is ended – because, for example, the market for the corresponding products is no longer there – the cooperation is continued in another project. Panasonic, for example, founded a joint venture with Toshiba in the area of color picture tube manufacture in 2003 (Matsushita, 2003, 2005). In 2006, after the previous cooperation was terminated and the production stopped because the color picture tube sales on the worldwide markets went down, a new joint venture was founded between the two Japanese firms for liquid crystal modules (LCD) and organic light emitting displays (OLED) technology (Toshiba_Matsushita_DT, 2008). Another case is Panasonic, which agreed to a joint venture with Hitachi in 2004 concerning shared research activities, manufacture, and distribution of LCD modules. The cooperation between Panasonic and Hitachi was ‘renewed’ and continued in 2008 in terms of research, manufacture, and distribution of LCD modules in the Czech Republic. Sharp, in another example, made an agreement with Sony in 1996 for the joint development of flat screen panels. In 2008, the joint project was ‘renewed’ when both Japanese firms started their common LCD panel manufacturing activities (DisplaySearch, 2008b).

Considering the complexities associated with operating an IJV, flexibility of the IJV parents is required to adapt to continuously changing conditions in the global markets (Zeira & Newburry, 1999: 338). Learning to manage IJVs is multifaceted, and the success of an IJV participating firm assumes a certain ability to absorb knowledge about work-ethics, communication behaviors, and business attitudes from the other IJV partner (Glaister, Husan, & Buckley, 2003: 103; Meschi, 2005: 692). Inter-organizational learning is a process where flexibility and adaptability are consistently important in assimilating the knowledge of the partner firm. Applying external knowledge from the partner organization involves the ability to diffuse knowledge, integrate it into the organization, and generate new knowledge from it (Lane, Salk, & Lyles, 2001: 1156–1157). Commitment to the IJV parent is dependent on the position taken by the other IJV parent. In light of this discussion, there are various reasons for IJV instability that the involved parties should keep in mind and work on when they arise.

- –First, one joint venture partner may show opportunistic behavior and attempt to hide proprietary knowledge, such as technological expertise, from the other joint venture participant. This behavior finally causes an IJV failure due to the lack of mutual trust and partners’ willingness to learn (Li, 1995: 347; Schuler, 2001: 9).

- –Second, tensions are created when either the IJV management or one of the IJV parents redirects its strategic focus, changes key objectives, attempts to reposition in the markets, or undertakes major growth or downsizing without prior appropriate communication to the partner.

- –Third, instability occurs when the partners renegotiate contracts (e.g., on technology transfer).

- –Fourth, the reconfiguration of the venture’s ownership and control structures represents a major source of instability because such amendments cause new bargaining dynamics and/or alter the strategic stakes of the partners (Yan & Zeng, 1999: 407). Lack of appropriate organizational structures, uncertain managerial roles, and indefinite decision authority negatively influence IJV performance (Schuler, 2001: 9). Diverse cultural backgrounds of the IJV partners hinder communication and may cause misunderstanding and reduced motivation of the IJV management (Frayne & Geringer, 2000: 406–407; Müller & Gelbrich, 2004: 367, 381).

- –A fifth facet of instability concerns the IJV’s relationship with each parent company. The IJV threatens to become unstable when changes take place that affect the decisional autonomy of the IJV management, such as limitation of their authority (Frayne & Geringer, 2000: 412; Yan & Zeng, 1999: 407).

- –Sixth, IJVs are often established in markets where the product is positioned at the declining stage of the technology life cycle. Instead of realizing the business reality, the partners hope that business performance will improve because they have bundled their mutual resources, which is often a fundamental mistake—as many firms experienced to their regret.

- –Seventh, IJVs are often founded in order to bring complementary resource assets together. For example, one partner contributes technological and engineering knowhow, and the other partner brings marketing expertise to the venture operations. At first glance, such an approach makes sense. However, engineers and marketers often speak a ‘different language’ and have different objectives (e.g., technological state-of-the-art versus costs and prices). This communication challenge is increased when engineers and controlling people and marketers have a different language and cultural background due to the different backgrounds of the joint venture parents.

- –Finally, major technological product developments on the market, unnoticed by one or both IJV partners, may damage the business performance and provoke disputes, which can lead to the termination of the IJV (Contractor & Lorange, 1988: 25).

To sum up, IJVs represent ‘mixed-motive games’ in which competitive and cooperative dynamics of the involved partners may occur simultaneously. The significant association of operational control with a partner’s achievement of its strategic objectives contributes to competition over resource allocation and pursuit of the unilateral goals of the partner firms (Yan & Gray, 2001: 411). Das and Teng (2000: 94) similarly claim potential different motives, such as cooperation versus competition, rigidity versus flexibility, and short-term versus long-term orientation. These differences create a framework of multiple tensions, which can cause partnership instability and finally the termination of the IJV.

3.3.2.3Case Study: International Joint Ventures of LG Electronics (South Korea) and Philips (The Netherlands)

3.3.2.3.1The partners’ situation before establishing their international joint ventures

LG Electronics (LG) is the second largest Korean Chaebol in consumer electronics after Samsung. Established in 1958, LG was originally known under the brand Lucky Goldstar. During the 1960s, LG produced Korea’s first radios, television sets, refrigerators, washing machines, and air conditioners. In 1995, renamed LG Electronics, the Korean conglomerate acquired the US-based enterprise Zenith. In 2008, LG introduced a new global brand identity: ‘stylish design and smart technology in products that fit our consumers’ lives’ (LG_Electronics, 2005a, b, 2009b). Over the years LG Electronics developed successfully, expanded worldwide, and became a serious competitor in the electronics business. However, the aggressive expansion was financed to a large extent by loans, which resulted in a critical debt-to-equity ratio. As a result of the financial crisis in Asia at the end of the 1990s, LG Electronics faced severe financial difficulties and needed to find external investors (Glowik, 2007b; LG_Electronics, 2008b).

At that time, the traditional and largest European-based electronics company, the Royal Dutch Philips from the Netherlands, was technologically already behind its Korean competitor in television flat panel manufacturing. Philips had a very reputable image with enormous brand recognition among European customers and had a large European sales network, which were the firm’s most valuable resource assets. The 1990s was a decade of organizational changes for Philips. The company carried out a major restructuring program, simplifying its organizational structure and reducing the number of business areas (Philips, 2008). In September 2006, Philips sold 80.1 percent of its semiconductor business to a consortium of private equity partners. This laid the foundation for a new independent semiconductor company, called NXP. In September 2007, Philips communicated its Vision 2010 strategic plan to further grow the company with increased profitability targets. As part of Vision 2010, the organizational structure was simplified in January 1, 2008, by forming three sectors: Healthcare, Lighting, and Consumer Lifestyle. With a massive advertising campaign to unveil its new brand promise of ’sense and simplicity’, the company confirmed its dedication to offering consumers around the world products that are advanced; easy to use; and, above all, designed to meet their needs (Philips, 2008).

3.3.2.3.2The foundation of LG.Philips LCD

In August 1999, the management of Philips took the chance to overcome its technological drawback in flat panel display technologies and decided to invest in LG Electronics. Philips paid USD 1.6 billion to LG Electronics and reserved 50 percent of the shares of the newly established joint venture, LG.Philips LCD. The partnership aimed for world leadership in the flat display television set industry. The capital investment was carried out so that Phillips purchased new stock (common shares) against payment to LG Electronics, which kept 98.8 percent of the subsidiary LG LCD shares it held before the transaction was completed (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2005a, b).

The joint venture with LG was not the first time Philips had tried to get into the LCD panel business through a partnership with another firm. Several years before, Philips experimented with developing its own production facilities with limited success. In 1997, Philips attempted to join forces and establish a joint venture with Hosiden Co., Kobe, Japan, a second-tier Japanese LCD manufacturer (Kovar, 1999). However, the joint venture failed and caused losses that reached more than USD 100 million a year (Bondgenoten, 2001).

At the beginning, the international new venture, LG.Philips LCD, was managed by a board of directors composed of six members, three each from LG and Philips. According to a press release dated May 19, 1999,

The alliance between LG Electronics Inc. and Philips (implemented through selling shares of LG LCD, the global electronic appliances manufacturer) is considered to have an important meaning from the perspective of competition strategy for the highly technical electronics industry, including LCDs. The alliance provides an opportunity for Korea to have absolute superiority in the leading-edge LCD industry because a synergy effect will be generated when the world-class technology of LG’s LCD is combined with the market reputation and distribution network of Philips (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2001).

In other words, besides the financial investment of Philips, which helped LG survive at the peak of the financial crisis in Asia, the Korean Chaebol could make use of Philips’ exclusive brand and distribution network in Europe and America. Previously, LG’s reputation in Europe was linked with a rather cheap, imitative manufacturer’s image; and the company name, ’Lucky Goldstar’, was rather promoting its low-end image among European consumers.

Headquartered in Seoul, South Korea, the newly established international joint venture, LG.Philips LCD, operated six fabrication facilities in China and South Korea and had approximately 15,000 employees, including those in South Korea. A new production site in Poland, responsible for the manufacture of LCD modules targeting the European market, launched production in 2007 (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2007a, b, c). LG.Philips LCD started to compete mainly against Samsung and Sharp in the segment that manufactures and supplies thin film transistor liquid crystal display (TFT-LCD) panels. The firm concentrated on TFT-LCD panels in a wide range of sizes and specifications for use in notebook computers, desktop monitors, and television sets (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2008a). On September 6, 2005, LG.Philips LCD announced that it planned to construct a ’back-end’ module production plant in Wroclaw, becoming the first global LCD industry player to commence such production in Europe. LG.Philips LCD considered building a production plant by 2011 with an annual capacity of 11 million units and an investment volume total of 429 million Euros. The manufacture of the LCD module began in the middle of 2007, when the construction of the first batch of module lines was completed with an annual capacity of 3 million units (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2006a, c). The vice chairman and CEO of LG.Philips LCD, Bon Joon Koo, said,

Our planned production facility in Poland is an important step for LG.Philips LCD, as we establish our manufacturing expertise in the geographic center of Europe. With this first major factory outside of Asia, LG.Philips LCD will better serve the rapidly growing European LCD TV market. As we implement our strategic plan for the future, we are proud to broaden the reach of our industry-leading LCD technology and expand our customer intimacy as we bring our products closer to our customers. We are grateful to the Polish government and the city of Wroclaw for their support and cooperation in this great partnership (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2006c).

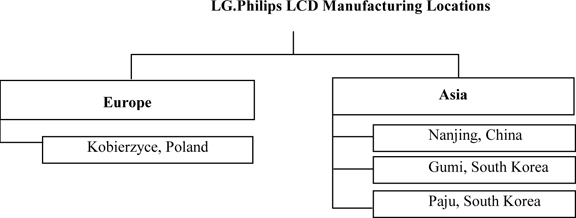

LG.Philips LCD relied on a worldwide manufacturing network. Major LCD display production plants were located in Asia and Europe, which provided various advantages in terms of manufacturing costs and logistics because of proximity to its regional markets (compare Figure 49).

Figure 49. LG Philips LCD manufacturing locations [status 2007]. Source: LG.Philips (2007a)

Global sales were organized by LG.Philips LCD mainly through three distribution clusters in Europe, America, and Asia, which served as a further strength relative to its competitors (compare Figure 50).

The investment of LG.Philips LCD in Kobierzyce (a suburb of Wroclaw) generated further market entry activities through direct foreign investment in Poland. The Japanese electronics enterprise Toshiba, for example, decided to set up a Polish subsidiary, assembling LCD TVs in Kobierzyce as well. Toshiba also operated an LCD factory in Plymouth, UK. The new Polish plant was scheduled to start operation by mid-2008. About 1,000 employees would manufacture between 1.5 and 2 million 32-inch and larger TVs annually (Johnston, 2006; LG.PhilipsLCD, 2007c). Toshiba’s annual production capacity of flat panel TVs in Europe, counting both UK and Polish output, reached around 3 million units by 2009. Toshiba’s factory procured large quantities of its LCD panels from the Dutch-Korean joint venture LG.Philips LCD. Toshiba invested 19.9 percent interest in the LG.Philips LCD plant in Poland. The developing industry cluster initiated the market entry of Korean component suppliers (follow the customer phenomenon). Various Korean firms decided to enter the Polish market and invested near the LG.Philips plant. Poland was becoming an important industry cluster in terms of vertically integrated LCD television set manufacturing outside Asia, which at that time was unique. From Poland, the module supply of LG.Philips LCD to other television set assemblers located in Europe was organized as Figure 51 illustrates (Johnston, 2006; LG.PhilipsLCD, 2007c).

Figure 51. LG.Philips LCD vertical integrated value chain activities in Europe (status February 2008).

In the years following the founding, LG.Philips LCD established various bilateral relationships with other firms doing business in consumer electronics. Stable supplier-customer relationships that secure economies of scale as well as the wish to develop a technological leadership positioning in the LCD business were the main incentives for seeking relationships for LG.Philips LCD. The networking activities of LG.Philips LCD led to the introduction of other partner firms with further distribution channels, competencies, and technological knowledge to the LG.Philips relationship network (compare Figure 52).

Despite a loss in 2001, net income increased in the years following the venture’s founding and reached a peak of around USD 1.5 billion in 2004. Overall, the global LCD business developed well, and LG.Philips was able to reap the rewards of it. The net sales of the international joint venture increased annually and reached more than USD 15 billion in 2007 (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2006d). Due to intense competition in the LCD business in the worldwide markets, the net income dropped in 2005 but progressively developed over the years. The data below illustrate the financial development of the joint venture (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2003, 2006b, 2008b).

3.3.2.3.3Philips reduces its stake in LG.Philips LCD

On March 3, 2008, LG.Philips LCD changed the name of the firm. The world’s second-largest manufacturer of LCDs, which began as a joint venture between South Korea’s LG Electronics Inc. and Philips in 1999, was renamed LG Display Corporation nine years later. Despite the promising financial development of the international joint venture, Philips finally decided to terminate its engagement. The Philips name disappeared from the title of the joint venture as result of the stepwise reduction in shares held by Philips. In October 2007, Philips reduced its stake from 32.9 to 19.9 percent, followed by a further reduction in March 2008 to 13.2 percent. As per December 31, 2007, LG Electronics, LG.Philips’ largest shareholder, held a 37.9 percent stake. Domestic (Korean) shareholders held 25.3 percent, and overseas investors and others held 16.9 percent (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2008c). In April 2008, Mr. Young Soo Kwon, CEO of LG Display, announced,

Figure 53. LG.Philips LCD net sales and income for the period 2001 to 2007. Developed based on various firm related sources (LG.Philips LCD, 2003, LG.Philips LCD, 2008b)

Last quarter was a notable quarter for us. Our performance was encouraging despite the seasonally slow market conditions. In addition, we have changed our corporate name from LG.Philips LCD Co., Ltd., to LG Display Co., Ltd., and will transition into a single representative director’s organization at the annual general meeting in accordance with the change in corporate governance following the reduction of Philips’ equity. The new name reflects our intention to expand our business scope and diversify the business model for sustainable growth in the future. While there were changes in our corporate governance, we remain committed to maintaining our integrity and being transparent and consistent, accompanied by our competent directors on the board (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2008c).

From this time onwards, LG Display Co., headquartered in Seoul, South Korea, concentrated its research and development in Anyang (South Korea) and maintained major module factories in Paju and Gumi (South Korea). In China, the firm established factories in Nanjing and Guangzhou. The one and only European module assembly line remains in Wroclaw, Poland.

Philips announced in February 2008 that it is looking to outsource manufacturing for 70 percent of its LCD TVs (in 2006 nearly 60 percent). The company expects to ship 14 million LCD TVs in 2008, with about 10 million units outsourced (Digitimes.com, 2008). In other words, Philips will further reduce its technological and manufacturing involvement in the television set business, taking the increased risk of losing know-how. According to the firm’s strategic plan, Philips will strengthen its activities in other business segments, such as lighting and healthcare, in order to be prepared for future markets (Emphasize_Emerging_Markets, 2007).

3.3.2.3.4The foundation of LG.Philips Displays

In Amsterdam, on June 11, 2001, Gerard Kleisterlee, president and chief executive officer of Royal Philips Electronics, and John Koo, vice chairman and CEO of LG Electronics, signed a ‘definitive agreement’ through which the two companies would merge their respective cathode ray tube (CRT) businesses into a new joint venture company. The official presentation of the new company was held on July 5, 2001, in Hong Kong. The fifty-fifty joint venture in display technology concerned all CRT activities, including glass and key components. With expected annual sales of nearly USD 6 billion and approximately 36,000 employees, the new company was expected to have a global leadership position in the CRT market. Philips paid USD 1.1 billion to LG Electronics. At that time, the joint venture held 25 percent of the global market share and ranked ahead of Samsung SDI in the CRT business. The following complementary strengths and synergy potentials of the merged entities were mentioned by both parties’ management (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2001a, b):

- –Philips’s leadership in television tubes and LG’s leadership in monitor tubes;

- –LG’s geographical leadership in Asia and Philips’ brand reputation and distribution network in Europe, China, and America; and

- –LG’s industrial and manufacturing expertise and Philips’ global marketing and technological innovation. Further benefits were expected in the areas of purchasing as well as research and development through combining resources and economies of scale effects (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2001b).

Under the terms of the agreement, LG and Philips had equal control of the joint venture. The new company was legally established in the Netherlands, with operational headquarters in Hong Kong. Philippe Combes, former CEO of Philips Display Components, was appointed to lead the joint venture (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2001a, b).

The television set market dramatically changed in 2004. While the demand for conventional cathode ray tubes went down, LCD and plasma sales increased. During the year 2006, LCD replaced conventional television set sales in Europe. Nevertheless, even in 2005, LG.Philips Displays still pronounced in a press release the bright future of conventional television sets and that the cathode ray technology would remain a dominant force in display technology, for example, through the introduction of ’slim tubes’ (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2005a, d). The venture management was totally wrong when it made such a forecast. Just two years later, in 2007, 26 million LCD sets were sold in Europe compared to only 10 million CRT-based units (Display-Search, 2008a; GfK, 2007). CRT manufacturers in general, among them LG.Philips Display, faced an increasing price pressure, particularly in highly competitive markets such as Europe. During the course of an increasing risk of running overcapacities, the culturally biased management behavior became increasingly obvious in the Korean-Dutch joint venture. Mr. David Kang, a manager of LG Electronics, explained his joint venture work experience to me,

There is a considerably different understanding among Western managers. They insist always on profits, the earlier the better. But our view is different and more long-term oriented. We enter the market with reasonable, well, let’s say with low prices. We may even have a loss. But what is more important? If we become the market leader, one day our products will set the standards. Then we will drive the market and its prices. From my point of view, these contrasting time horizons are one of the main reasons why joint ventures of Western and Korean companies fail (Glowik, 2007a).

Concerning different work attitudes and language barriers, Mr. Kang further commented,

When we had a problem with the customer, for example, it was sometimes hard to find a Western manager when it happened out of the ordinary daily working time. We Koreans cannot understand such customer treatment. For the Europeans, it seems more important to arrange the time with their private families. We Koreans work hard; we have a lot fewer holidays, but the Philips people had 2.5 times higher salaries than we had. How can a joint venture run like this in the long term? Moreover, I have to say, we had a communication problem. English was selected as the company language, but Koreans have weaknesses communicating in English (Glowik, 2007a).

The European view of the joint venture was different. A former senior manager at LG.Philips Displays, who preferred to remain anonymous, commented about the working atmosphere in the international joint venture like this,

When we (Philips) had a meeting with LG people, sometimes they kept silent the whole time. Later, we recognized the Koreans arranged a separate meeting among themselves, where they discussed and fundamental decisions were made . . . without us. Moreover, I think the Koreans had very effective conversations among themselves in the ’smoker’s room’ more than during official meetings with us. It is hard to cooperate and get access to them. The Korean community is rather a closed shop (Glowik, 2004a).

Just two years after the establishment of the joint venture, on May 22, 2003, LG.Philips Displays announced the closure of its European production plants in Newport, Wales, and Southport, England, and that the management had started consultations with employees and trade union representatives (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2005b, c). The corresponding press release said,

The decision is based on business and economic conditions, which are characterized by an increasingly competitive and consolidating industry. The company’s plant at Newport in South Wales produces color display tubes (CDT) for monitors and color picture tubes (CPT) for televisions as well as deflection yokes. A sharp decline in the market for CDTs due to increasing competition from other display technologies also supplying products for use in computer monitors and severe downward pressure on prices for CDT and CPT are the primary reasons for the closure (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2005c).

Phil Styles, general manager of manufacturing at Newport, commented,

The decision to close was made with great regret and is based solely on the continuing adverse business situation. It in no way reflects on the performance of the employees at the plant, who have worked hard and demonstrated considerable commitment over these past five years (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2005c).

Just a couple of months later, on December 2, 2003, LG.Philips Displays announced a decision to further restructure its industrial production infrastructure in Europe. As announced by the management,

The measures, in line with the company’s continuous drive for optimizing business performance, are necessary to remain competitive in a mature and consolidating industry. As a consequence, the company’s cathode ray tube plants in Aachen, Germany, and a glass factory in Simonstone, UK, will be shut down. At all other sites in Europe, cost reduction will be realized by further optimizing the production infrastructure (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2005e, f).

In the following years, LG.Philips continued the closing process, mainly of its European facilities. On March 2, 2005, LG.Philips Displays published the closure of its plant at Durham in North East England. As was stated in the press release,

Crippling price erosion and a shift in demand from Europe to Asia Pacific are the main reasons for the decision, which has been made with great regret. Consultations with employees and trade union representatives have begun. Production is expected to cease towards the end of July 2005 and will result in the loss of 761 jobs (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2005b).

Finally, in October 2005, Philips announced that it would stop television set manufacturing for the European market, which affected its major supplier LG.Philips Displays and particularly its brand new factory in Hranice, Czech Republic, as well as its R&D and manufacturing facilities in Angers, France. Nevertheless, major production operations in Asia and some in Brazil, representing 85 percent of total manufacturing capacity, as well as minor European component suppliers (Stadskanaal and Sittard, The Netherlands, and Blackburn, United Kingdom) continued activities (LG.Philips-Displays, 2005e, 2006, 2007a).

Three months later, on January 27, 2006, LG.Philips Displays Holding B.V. announced that due to worsening conditions in the cathode ray tube marketplace and unsustainable debt, the holding companies as well as one of the Dutch subsidiaries (LG.Philips Displays Netherlands B.V.) and its remaining legal German subsidiary in Aachen, Germany, had all filed for insolvency protection. The holding company of LG.Philips Displays in Hong Kong also announced that it would not be able to provide further financial support to certain loss making subsidiaries (in Europe) because it had been unable to obtain sustainable new or additional funding. As a result, approximately 350 employees at the company’s operations in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, and 400 employees in Aachen, Germany, were dismissed (LG.Philips-Displays, 2006). Concerning the insolvency filings, LG.Philips Displays headquarters in Hong Kong officially declared in a corresponding press release,

Over the past year, LG.Philips Displays and other CRTmanufacturers have seen an unprecedented decline in the market for CRTs, especially in Europe. At the same time, the demand for new flat panel televisions, including liquid crystal display (LCD) and plasma televisions, has surged dramatically as these alternatives have dropped in price and become cost competitive faster than anticipated. Although demand for CRTs has dropped precipitously in mature markets, global demand for CRTs remains strong, especially in emerging markets. LG.Philips Displays has been in extensive discussions with the company’s financiers and parent companies, Philips and LG Electronics, over the past several months to explore financial solutions to the market challenges, especially in Europe (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2006).

The president and CEO of LG.Philips Displays, J.I. Son, commented,

We deeply regret this outcome and the painful impact these filings will have on our valued employees and the communities that have supported us over the years. Unfortunately, market conditions and our financial situation have made this very difficult decision unavoidable. Having explored all possible restructuring options, we really have no choice but to take these actions. We are working to maintain employment for our remaining employees through our ongoing operations (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2006).

In the course of its retrenchment strategy, additional subsidiaries of LG.Philips Displays in France, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Mexico, and the US were liquidated. LG.Philips Displays emphasized that its plants in Brazil, China, Indonesia, South Korea, and Poland (component supplier) were, in principle, unaffected. The company’s factories in the United Kingdom (Blackburn) and the Netherlands (Stadskanaal and Sittard, with support from some employees in Eindhoven) were economically viable and were expected to continue production, for which LG.Philips Displays would seek support and approval from the Dutch trustee and supervisory judge (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2005e, 2006).

In fact, the LG.Philips Displays joint venture operations resulted in a loss just after the firm’s foundation. The financial situation could not recover in the following years. What are the reasons? The European television set cathode ray tube market declined due to the fact that the CRT technology had reached the end of its product life cycle and had been replaced by flat panel technologies. Consequently, competition had become more and more price focussed. The remaining tube supplying manufacturers in Europe, such as large firms like Samsung, Thomson, and Matsushita but also small competitors like Ekranas (Lithuania) and Tesla (Czech Republic) operating in niche markets, were seriously competing for survival. Additionally, Chinese cathode ray tube manufacturers increased their shipments to Europe and worsened the attractiveness of the market. In parallel, the venture partners from contrasting cultural backgrounds could not solve internal communication problems, which had a negative impact on performance as illustrated below (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2001a, 2007b).

Figure 54. LG.Philips Displays’ net sales and net income for the period 2002 to September 2005. Source: LG.Philips Displays (2005f, 2007a)

In 2001, when the joint venture with LG Electronics was established, the television set business unit of Philips had a turnover of USD 3 billion, ran twelve cathode ray tube production sites with 24,000 workers worldwide, and reached a profit of USD 157 million (Bondgenoten, 2001). Just a couple of years later, the former European market leader in consumer electronics, Philips, had disappeared with the joint venture bankruptcy and simultaneously disappeared from the cathode ray tube television set business (TheInquirer, 2006).

3.3.2.3.5LG.Philips Displays gets a new name

Effective on April 1, 2007, LG.Philips Displays changed its name to LP Displays. The corresponding press release by the top management said,

The new name and stylized logo are designed to reflect its new corporate status while saluting its roots as a joint venture between LG Electronics and Royal Philips Electronics. At the same time, it reinforces continuity in LP Displays’ position as one of the world’s leading global suppliers of picture tubes used for television sets and computer monitors. The new name and the logo act as an important step forward for LP Displays and reflect the management and financial stakeholders’ confidence in both the future of the company and the CRT business (LG.PhilipsDis-plays, 2007c).

LP Displays continued to focus its business on high performance CRTs and a growing demand for its ’SuperSlim’ and ’UltraSlim’ CRTs, particularly in emerging markets. The global demand for CRTs was expected to remain strong. LP Displays president and CEO, Mr. Jeong IL Son, commented,

Of the countries with the largest populations, the majority will be CRT customers for the foreseeable future. Markets in Asia and South America offer the company an exciting challenge going forward, and the ’UltraSlim’ and ’SuperSlim’ series provide LP Displays the competitive advantage it needs to capture this tremendous opportunity (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2007c).

LP Displays’ management team remained in Hong Kong under the leadership of Mr. Son. The company continued to serve its global markets from its plants in Brazil, China, Indonesia, and South Korea and from its minor component operations in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. LP Displays continued to employ around 11,000 people worldwide. The company’s new name and logo reflected the change in ownership structure. Dutch representatives disappeared completely from the firm, which was originally established in 2001 as a fifty/ fifty joint venture with a payment of USD 1.1 billion by Philips. A couple of years later, the top management consisted of Korean managers only: Mr. Jeong IL Son, president and chief executive officer; Mr. Deok Sik Moon, chief financial officer and deputy chief executive officer; Mr. J.M. Park, chief sales officer; and Mr. Soo Dyeog Han, executive vice president of New Business Development (LG.PhilipsDisplays, 2007c).

3.3.2.3.6What happened next to the international joint venture terminations?

Without the financial involvement of Philips, it is questionable whether LG could have recovered and developed successfully after the Asian financial crisis as they have done in recent years. On the one hand, the management of Philips underestimated the sharp decline in conventional cathode ray tube TV demand when the company decided to invest in the joint venture with LG Electronics. On the other hand, the Philips’ management obviously did not foresee that LCD/LED technology would drive the business at least for the next decade when they decided to leave the LG.Philips LCD joint venture in 2008. Moreover, the management of Philips did not pay attention to the absorptive and learning capabilities of LG Electronics’ management. Meanwhile, the European joint venture partner, Philips, lost its vertical manufacturing integration in the consumer electronics business. Today (year 2016), we can still buy consumer electronics products such as television sets, audio, and others where the Philips brand is labelled on the outside of the product. Most customers believe the product is from Philips. However, the reality is that it is assembled by Taiwanese, Chinese, or other firms, usually based on a manufacturing contract with Philips.

During the international joint venture operations, LG Electronics gained access to the European distribution channels and learned about proper marketing instruments suitable for the European consumer. For instance, LG has changed the meaning of its initials to ‘LG = Life is Good’, hoping to get closer to its European customers. The strength of LG Electronics is its technology and research and development expertise. Through its new LCD module plant in Poland, the firm has become able to supply LCD modules to the factory of LG Electronics in Mlawa, Poland, which assembles final television sets and supplies them to the whole European market. Following the joint venture termination, LG Electronics could have significantly increased its net sales on the global markets. Nevertheless, net income has not increased over the years; but the Korean company has performed better than, for example, firms like Sony or Panasonic in terms of net income during recent years (compare Figure 55).

Figure 55. Net sales and net income of LG Electronics for the period 2003 to 2014. Developed based on various firm related sources (LG_Electronics, 2003, 2004, 2005a, 2006, 2007, 2008a, 2009a, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014)

At present, LG Electronics makes use of its LCD/LED display technology expertise and expands into new business fields such as automotive. The Korean company develops innovative automotive infotainment devices, including monitors and navigation systems. Aside from in-vehicle infotainment, LG also offers safety, engineering, and electric vehicle solutions that target autonomous driving (LG_Electronics, 2015b). LG’s new vehicle components division combines component-related business units by merging the car infotainment unit with the home entertainment division. LG Electronics’ newly launched division called Energy Components develops motors for electric vehicles as well as inverters and compressors (LG_Electronics, 2015a, d). The home entertainment division, with its wide range of LCD/LED and OLED products, will remain one of the most important business units within LG Electronics for the coming years (compare Figure 56).

- Describe the resource strengths and weaknesses of the joint venture partners, LG Electronics on the one side and Philips on the other side, before they established LG.Philips LCD and LG.Philips Displays.

- Explain the crucial milestones during the LG.Philips LCD joint venture operations.

- Describe the major reasons that the LG.Philips Display joint venture failed.

- What mistakes, from your point of view, did the Philips management make in terms of the joint venture operations LG.Philips LCD and LG.Philips Display?

3.3.3Hierarchical modes of market entry

3.3.3.1Foreign direct investment

As the foreign business develops successfully, the firm may consider enlarging its engagement in its target markets abroad through foreign direct investments (FDI), which has several forms (Rugman & Hodgetts, 2003: 41). The establishment of a sales branch represents the lowest form of financial involvement in the category of foreign direct investment. The institutional character of an FDI is mirrored by constant interaction and personal contact with actors in the host country in the course of day-to-day business activities. Aside from necessary resource transfers, such as financial, the issue of staff mobility and corresponding expatriate training arises in this context. The extent to which local and expatriate personnel are employed in the host country depends on the target market business volume, the size of the facilities, and the degree to which the foreign branches are embedded in a sales and distribution network (Duelfer & Joestingmeier, 2011: 152–153).

A firm investing abroad combines firm-specific advantages developed at home with other assets available in the foreign country (Hennart & Park, 1993: 1055). The term wholly owned subsidiary (WOS) describes an enterprise that owns all of the capital invested abroad, such as, for example, research and development, sales, and/ or manufacturing facilities. The firm either sets up an entirely new operation (start-up or greenfield) or it acquires partial share (equity participation) or takes over completely an established firm in the target foreign country (Hitt et al., 2015: 197–198). The firm’s resource availability and the firm-specific objectives determine whether the market entry will be either through firm-specific resources or external, through acquisitions. Firm-specific resources may consist of superior organizational ability, market knowledge, or technological expertise. Acquisitions come along with the advantage that the firm can combine its own resource advantages with those of an acquired foreign firm. The firm can acquire technological knowledge, foreign market knowledge, and a skilled labor force. A valuable brand reputation can be obtained, which might have taken years to build up; and, thus, immediate pressure from competition may be substantially reduced (Penrose, 1995: 127).

There are two different types of acquisitions: An international horizontal acquisition is made in order to realize the firm’s growth strategy through expanding in foreign markets. A firm acquires another organization positioned in the same location of the industry chain abroad. Horizontal acquisitions provide prerequisites to increase the overall market share of the firm and usually provide potential for cost reduction because of larger operational capacities resulting in economies of scale effects. In the case of an international vertical acquisition, a firm either acquires a foreign supplier (backward integration) or a distributor (forward integration) in the target market abroad (Hitt et al., 2015: 197–198). The new external knowledge from the acquired firm needs to be integrated and combined with the existing internal knowledge. By assimilating the acquisition partner’s knowledge and best practices, acquiring firms can enlarge their knowledge base, which helps a firm to adapt itself to the foreign market environment. The absorptive capacity of the acquiring firm influences the performance and effectiveness of its business operations in the foreign market (Zou & Ghauri, 2008: 212).

Nevertheless, in spite of all the advantages, an acquisition is by no means a universally available strategy for international market entry nor does it allow a firm automatically to escape from limited resources. More autonomy for the acquired business organization may provoke the risk of conflicts with the acquiring company’s policies and activities and result in increased difficulties of working out an appropriate subsidiary-headquarters relationship. In consequence, there is a limit to the rate of expansion by acquisitions because consistent general policies have to be worked out and integrated between the acquired firm and its new headquarters. Operations, marketing, and accounting procedures need to be coordinated; and personnel policies and numerous other challenges need to be managed. For example, talented and highly skilled employees may leave the acquired firm. These challenges may offset the benefits derived from the acquisition of an established operation (Hill, 2012: 413) Therefore, financial, managerial, and organizational resource limits on the rate of expansion imply that no company can acquire every likely firm in sight in any given period of time. A firm has to choose carefully; and since mistakes may be costly and not always reparable, those target firms should be selected that seem most likely to complement or supplement existing resources. Acquisition decisions are influenced by the predilections and experience of the management and the expected profitability input of the acquired firm, which depends on the price paid compared with the expected contribution to the earnings of the acquiring firm (Penrose, 1995: 129).

An alternative to an acquisition is a greenfield investment, where the firm newly develops and builds up facilities. Necessary resources to start up a new business in the target foreign market have to be make available by the internal efforts of the firm (Brouthers, Brouthers, & Wilson, 2001: 27). In contrast to an acquisition, the establishment of a firm through a greenfield investment (foreign start-up) entails building an entirely new organization. Companies often establish start-ups by sending expatriates, who select and hire local employees and gradually build up the business. Through its expatriates, the parent firm can train the new labor force, which makes it possible to better incorporate the company culture compared to with an acquisition, particularly in the case of a hostile takeover (Barkema & Vermeulen, 1998: 9). Brouthers and Brouthers (2000: 96) claim that firms that have developed strong capabilities, especially in the areas of technology and international operations, tend to favor greenfield investments instead of acquiring existing facilities.

Another entry mode through an FDI, called a merger, is where two firms amalgamate their resources to form a new company. International mergers typically involve firms of similar size with different national origins. Mergers are sometimes preferred to an acquisition in order to minimize the mental reservations of the national governments that may be involved, depending on the strategic importance to the local economy (Grant, 2013: 396–397). Figure 57 provides an overview of FDI alternatives.

The main advantage of market entry through the establishment of a wholly owned subsidiary is hierarchical control over decision making, which is important, for example, regarding quality assurance and the protection of intellectual property rights. Further advantages of FDI derive from the closeness to the market and its customers. This proximity improves the local product development and increases cultural sensitivity in marketing communication. A wholly owned subsidiary can be integrated (and controlled) in the firm’s overall strategy when approaching diverse regional foreign markets (Deresky, 2014: 221–222). Additionally, some nations – for example, central and eastern European countries that joined the European Union in 2004 – support foreign investments with tax benefits and infrastructure developments in the case of greenfield projects. Assuming that quality and production efficiency is equal relative to the home country, the firm may enjoy additional cost savings due to low labor expenses.

Challenges that come up with the establishment of wholly owned subsidiaries arise from the increased planning and coordination complexity of foreign and local operations. The firm may underestimate culturally biased differences reflected in work ethics, quality consciousness of the employees, and loyalty toward the enterprise. Subsidiary operations have to be prepared to accept centrally determined decisions concerning production output, product portfolio, service mission, human resources, and price policy for the incoming and outgoing units (Hill, 2012: 498). The wholly owned subsidiary in a foreign country entails, among all market entry concepts, the highest uncertainty and investment risk (Hitt et al., 2015: 246).

Arora and Fosfuri (2000: 569) concluded from their research that managerial learning curve effects influence the choice of the firm’s foreign operations. Prior experience in the host country increases the odds that the project will be carried out through a wholly owned operation rather than through, for example, licensing. Similarly, Barkema et al. (1996: 164) argue that firms entering foreign markets face cultural adjustment costs. The management takes advantage of the learning curve, especially when it chooses the expansion path in such a way that it can exploit previous experience in the same country or other nations with similar cultural characteristics.

3.3.3.2The case study of Lenovo: Growth through acquisitions

In 1984, Legend Holdings was founded with USD 25,000 in China. In general, Lenovo is the result of the merger between Legend Holdings, at that time the most important technology company in the Chinese market, and the former Personal Computer Division of IBM. Consequently, the IBM product line ThinkPad was also acquired. Following the acquisition, the company changed its name to Lenovo in 2004 (Lenovo, 2013).

After acquiring the German consumer electronics company Medion in 2011 and the Brazilian CCE in 2013, Lenovo became the largest global PC company (Rhally, 2014). Moreover, the enterprise acquired the mobile phone assembler Motorola from Google for USD 2.91 billion in 2014 in order to benefit from Motorola’s relationships with several telecommunication partners, its 8000 US patents, and an additional 15,000 patents related to other foreign countries (Osawa, 2014a; Rhally, 2014). In recent years, Lenovo completed additional important acquisitions and agreed to two international joint ventures (Lenovo, 2013a, 2014b):

- –2011 Joint venture of Lenovo and NEC (became largest PC company in Japan)

- –2012 Joint venture of Lenovo and EMC (took advantage of server and enterprise solutions)

- –2012 Acquisition of Stoneware (cloud-specialized software company)

Lenovo expanded its position in the global PC, tablet, and smartphone market behind well-known competitors like Apple and Samsung. In 2014, Lenovo PCs, tablets, and mobile smart phones reached around 45 percent of the world’s population. Lenovo aims to become a multinational corporation instead of appearing to be a pure Chinese company. The management is made up of six different nationalities. Although the management leadership is based in China and the company is listed in Hong Kong, additional top executives are from Raleigh, Silicon Valley, Singapore, and Tokyo (Rhally, 2014).

Currently (status September 2015), Lenovo is led by chairman and CEO, Yang Yuanqing. The Chinese electronics firm employs 33.000 people in 60 countries, serving customers in more than 160 countries. Because of Lenovo’s progress in global expansion, the locations of administration and sales branches, research centers, and manufacturing factories are distributed all over the world. Headquarters are located in Beijing and Raleigh, with research centers in several cities of Japan, China, and the USA. Manufacturing factories are located in the USA and China as well as in Mexico, India, and Brazil (Lenovo, 2013a, b).

Lenovo’s product line consists of ‘Think’ branded PCs; ‘Idea’ branded PCs, servers, and workstations; and ‘Yoga’ branded tablets and smartphones. The major goal of Lenovo is to become number one in ‘Smart Connected Devices’, combining PCs, tablets, and smartphones (Lenovo, 2013a). As far as the company’s internal structures are concerned, four business groups were created, including PC, mobile, enterprise, and ecosystem/cloud divisions as illustrated in Figure 58 (Lenovo, 2014c; Osawa, 2014b).

Lenovo sharply increased its net sales beginning in 2010 from USD 16.6 billion up to USD 38.7 billion in 2014 (compare Figure 59). Except for the year 2009 (loss of USD 0.23 billion), Lenovo continuously generated profits over the last years, although the profits were rather marginal (average around 2 percent of net sales) (Lenovo, 2014a, 2015). On one hand, Lenovo is operating in highly competitive markets (e.g., PC, tablets, etc.). On the other hand, Lenovo’s own innovative capabilities – which were not gained through acquisitions such as IBM PC division, Motorola, and others – are still questionable (Lenovo, 2014d).

Figure 59. Net sales and net income development of Lenovo Group Limited from 2006 to 2014 (Lenovo, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013b, 2014a, 2015)

And how good is Lenovo’s global brand reputation?

In 2005, the company became positioned among leading enterprise-solution products with its ThinkPad. Then Lenovo tried to attract the customer’s attention to consumer-centric products, such as the Yoga tablet (Rhally, 2014). In order to improve its brand awareness and reputation, Lenovo developed a comprehensive marketing strategy by advertising Lenovo as a global brand. Ever since Lenovo bought Motorola, there has been a lot of speculation as to what it would do with its existing mobile division. Lenovo has recently provided more details, saying it would run all of its smartphone operations under the Motorola umbrella and eventually shut down its business unit, Lenovo Mobile. Lenovo commented in a statement that ‘effective immediately, Rick Osterloh, formerly president of Motorola, will be the leader of the combined global smartphone business unit’. Mobile employees will join Motorola; and, as reported earlier, Motorola will take over all design chores (Dent, 2015). In the course of its efforts to become a global player, Lenovo should take care not to lose its customers in China, a large and still very important domestic market (Rhally, 2014).

- Applying your theoretical knowledge to the Lenovo case, describe the advantages and disadvantages of market entry through acquisitions.

- From your point of view, describe what it would be like to be in the shoes of Lenovo’s management. What resource strengths and weaknesses did Lenovo have in the past, and what should be done in the future?

- Reflecting on Lenovo’s global strategy ambitions, describe and discuss the opportunities and potential risks for the firm’s management.

3.4Decision Determinants of an International Market Entry

3.4.1Entry rapidity and proximity to the market

The strategic concept of international market entry requires a clear formulation of the firm’s objectives in the target foreign market. Objectives are a statement as to what the company will achieve within a certain period of time in terms of market position, return on investment, and the development of key business sectors in the target countries (Hibbert, 1997: 137).

An innovator’s (technologically leading) strategy linked with skim pricing offers the opportunity to sell the products at a relatively high price level to the innovation-seeking customers in the target market abroad. Because of the product and/ or service novelty, competitors are rather few (first-mover advantages of the innovator). Disadvantages derive from delayed market penetration and the risk that competitors appear in the course of time and take advantage of higher sales volumes. If fast market penetration is desired, the firm decides on a pricing strategy that attempts to accelerate market penetration and offers the foreign firm the opportunity to expand the target market share and make use of experience curve effects in order to further lower the price and finally dominate the industry (Wheelen & Hunger, 2010: 241). Potential risks arise from the defensive strategies of local firms, which may range from severe price competition to lobbying their local governments for support.

Market entry timing targets significantly influence the selection of the firm’s entry strategies. Consequently, the length of time it takes to implement an international market activity represents an important decision-making criterion. On the one hand, a firm may be trying to achieve foreign market entry as rapidly as possible. For example, a firm might have developed a new product in a market where the technology is changing rapidly, such as in high-technology industries or where the product development can readily be copied by competitors, so as rapid an exploitation as possible is required. In such cases, export or licensing activities are more desirable than, for example, greenfield manufacturing investments, which are likely to be inappropriate because of the complexity of the project abroad and the corresponding time delay. On the other hand, if exporting is impeded through non-tariff barriers by the foreign government, contract manufacturing or licensing arrangements may be the fastest means of market entry. In operations through which the manufacturing function is internationalized and relocated to the foreign market, such as contract manufacturing and wholly owned foreign production, the international business in the foreign target market is not affected negatively because the operations take place inside those barriers. The firm secures a closer proximity to the target market abroad, which provides first-hand information to the firm (Luostarinen & Welch, 1997: 240). The less standardized the product and service and the more different the customer expectations in terms of quality, design, and purchasing attitudes, the more desirable it is for the firm to be as close as possible to the market.

3.4.2Degree of hierarchical control and financial risk

The choice of entry modes comprises the essential decision of locating the firm’s value-added activities and the level of operational control. Manufacturing resources might be either located domestically and are completely controlled by the firm or shifted partially or completely abroad (Hollensen et al., 2011: 8). The degree of hierarchical control of operations and the associated financial risk differ depending on the selected entry mode (Zhao, Luo, & Suh, 2004: 540). The degree of control and financial risk can be divided into four categories.