Chapter 3

The Two Phases of Perceiving People

Already something of a success on Broadway, a young dancer from Omaha, Nebraska, was eager to finally make his big break into film. His initial attempts, however, did not go as well as he had hoped. After viewing his MGM screen test, an associate producer there dismissed him, saying, “You can get dancers like this for seventy-five dollars a week.” The dancer’s first screen test for RKO Radio Pictures wasn’t any better—this time, the report came back: “Can’t act. Slightly bald. Also dances.” True, he wasn’t the handsomest young man to ever try to make it in Hollywood. And he was balding, and a trifle too thin.

Fortunately for the young man in question, famed studio executive David O. Selznick, best known for producing Gone with the Wind, decided to give him a chance. Selznick had really studied the screen test, giving it his full attention—and saw something the others didn’t. “I am uncertain about the man,” he wrote, “but I feel, in spite of his enormous ears and bad chin line, that his charm is so tremendous that it comes through even on this wretched test.” That charmer, if you haven’t guessed it already, was Fred Astaire.1

“You can get dancers like this for seventy-five dollars a week”? We’re talking about the same man George Balanchine would later call “the most interesting, the most inventive, the most elegant dancer of our times.” Mikhail Baryshnikov would call Astaire’s dancing “unmatched perfection.” “Can’t act”? You could have fooled me. Astaire received numerous Emmys and Golden Globes, and an Academy Award nomination for his acting. “Slightly bald”? OK, true—but so what? That didn’t stop the American Film Institute from naming him the fifth Greatest Male Star of All Time—right behind Humphrey Bogart (he of no great chin line himself), Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, and Marlon Brando.

. . .

Mistakes like those made by Fred Astaire’s screen test viewers happen because our perception of other people has two distinct phases. And more often than not, our cognitive miser never lets us past the first—very flawed and biased—phase.

Harvard’s Dan Gilbert, whom you may know as the author of Stumbling on Happiness or as the host of PBS’s This Emotional Life, also happens to be a central figure in the study of what he calls ordinary personology, the “ways in which ordinary people come to know about each other’s temporary states (such as emotions, intentions, and desires) and enduring dispositions (such as beliefs, traits, and abilities).”2 Gilbert’s seminal work with Brett Pelham and Douglas Krull at the University of Texas at Austin in the 1980s provided us with the essential insight that perceiving other people is a two-phase process.3

Imagine you observe someone weeping at a funeral. In Phase 1 of perception, you (as the observer) ask yourself, What is it about this person that is causing him or her to cry? Weeping, for instance, implies that someone is particularly emotionally sensitive. You aren’t actually aware that you are asking (and answering) this question. It happens automatically, below your awareness, and in fractions of a second. It is also relatively effortless and riddled with biases that shape the conclusion you ultimately draw.

In Phase 2 of perception, you engage in correction or discounting, by taking into account other factors, like the situation the behavior is occurring in. After all, lots of people cry at funerals, right? So weeping at a funeral, upon further consideration, doesn’t really suggest that the person is particularly sensitive—anyone might behave that way under the circumstances.

For those of you who have read Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, you may have already recognized that Phase 1 of perception is part of what Kahneman calls System 1, the mental operations that are automatic, relatively effortless, and (almost) completely out of our awareness and control. It includes our abilities to instantaneously recognize anger in a person’s face or voice, to drive a car on familiar roads while carrying on a conversation with a passenger, and to know that 2 + 2 = 4 without having to actually add anything. And it relies on all the assumptions and biases described in chapter 2. System 1 is also always on—you don’t even have the option of turning it off.4

Phase 2 of perception is part of System 2, the mental operations that are complex and effortful, require attention, and are usually done with conscious awareness. System 2 engages when necessary, and only when necessary. It includes our abilities to craft a careful apology to the person we’ve angered, to drive a car in a foreign country on the opposite side of the road we normally drive on, and to work out problems like 21 × 53 = x. System 2 operations do the heavy lifting, when getting something right is hard and it really matters.

If we are to get a complete and accurate understanding of someone, Phase 2 processing is absolutely necessary. Unfortunately, Phase 2 is very effortful. It takes some serious mental work to weigh all the possible factors influencing someone’s behavior and to try to avoid bias. So we need to be motivated to do it—otherwise, we don’t reconsider the snap judgment we reached in Phase 1.

Gilbert and his colleagues illustrated this two-phase process by manipulating the ability of perceivers to enter Phase 2. In their most famous study, they asked female participants to watch seven video clips of a young woman having a discussion with a stranger, ostensibly as a part of a getting-acquainted conversation, and to form an impression of her. Each clip was subtitled to indicate the topic the woman and the stranger were discussing, as there was no sound. In five of the clips, the young woman was visibly anxious and uncomfortable.

Gilbert varied the subtitles, so some of the participants were led to believe that the young woman was discussing anxiety-producing subjects—like hidden secrets, personal failures, embarrassing moments, and sexual fantasies. The others were told that she was discussing more-neutral topics during those clips—great books, best restaurants, and world travel.

Finally, half of the people in each group were kept cognitively busy by being asked to simultaneously memorize the conversation topics. This, the researchers reasoned, should make it much more difficult for the perceivers to enter Phase 2, since Phase 2 processing is effortful and mentally taxing. Having to memorize should leave the perceivers too preoccupied to take into account the situation—discussing stressful or neutral topics—when forming an impression of the young woman.

After viewing the video clips, each participant was asked to rate the extent to which she believed the young woman to be an “anxious person.” Figure 3-1 shows that when perceivers were not mentally busy—when they could enter Phase 2—they were able to successfully take the situation into account. So, when the young woman appeared anxious discussing topics that would make anyone anxious, they did not conclude that she was an anxious person.

FIGURE 3-1

Is she an anxious person?

When they were busy, observers of a woman under stress were less likely to take context into account.

Source: Daniel Gilbert, Brett Pelham, and Douglas Krull.

But when perceivers were mentally busy and could therefore only go with their Phase 1 assessment, they rated the young woman as almost equally anxious regardless of the context. In Phase 1, acting anxious is equivalent to being an anxious person, end of story.

Think about that for a minute, because the implications of these observations are astounding. How often are we mentally busy—preoccupied, multitasking, stressed—when we perceive other people? More to the point, how often are other people mentally busy when they are perceiving you? Yes, they are capable of weighing all the factors that may be influencing your behavior under ideal circumstances, assuming they actually know all the factors and are motivated to weigh them. But let’s face it, in our everyday lives, circumstances are generally far from ideal, and other people aren’t necessarily committed to being right about you. So perception stops at Phase 1 much of the time.

In addition, all of the cognitive biases discussed earlier are setting the stage for bias, even before Phase 1 begins. In this pre–Phase 1 stage, we assign some meaning to the action we’re observing—we categorize the behavior in some way. We tend to identify actions in terms of their intentions, whenever possible. As a result, we don’t think to ourselves, Frank’s fist connected with the side of Bob’s face. We think, Frank punched Bob. Even though both statements are equally accurate, punching conveys the sense of intent—that Frank was trying to hurt Bob, not accidentally falling into his face with his fist.

I mention this distinction because interpretation—the loss of objectivity—begins with the very act of seeing the behavior itself. Recall the young woman from Gilbert’s experiment—the one who was acting anxious in the video clips. She seemed agitated, restless, uncomfortable. She avoided eye contact. People tended to agree that this behavior constituted “anxiousness.” But given that women are generally believed to be more emotional than men, and more prone to anxiety, would a male target behaving in the same manner have been seen as equally anxious, or might those same signals come across as something more “masculine”—like frustration, impatience, or boredom? Remember that automatic, unconscious biases influence our perception even before Phase 1 begins, directing everything that follows down very different paths.

So you can’t really blame people for what they “see” at Phase 1. Well, you can, but you would be blaming them for something they have no awareness of or control over. Which would not be particularly fair, especially since you do it, too.

Hopefully by now it has become obvious that you cannot simply sit back and expect other people to do a better job of judging you accurately. You are going to need to get actively involved.

So let’s first take a look now under the hood of Phase 1 perception. You’ll learn how it runs entirely on autopilot, how it prefers one kind of explanation for behavior above all others, and how, in light of limited information, it paints a picture of you using the broadest of possible strokes—traits.

Phase 1 of Perception

What does it mean for something to be automatic? Psychologists generally agree that for a behavior to count as automatic, four conditions must hold true: (1) the behavior happens without awareness, (2) it occurs without conscious intent, (3) it is relatively effortless, and (4) it is largely, if not completely, uncontrollable. Decades of research show that the operations that occur in a perceiver’s brain when he or she is assigning meaning to your behavior and deciding what your behavior says about you meet all four requirements of automaticity.

Perceivers start by assuming that whatever you are doing, it reflects something about you—some aspect of your personality, character, or abilities. This, as I mentioned before, is the go-to explanation for all things in Phase 1. Psychologists call this correspondence bias—as in, we are biased to see a behavior as corresponding to its actor. Thus, you were late to the meeting because you are not conscientious. Maria lost her temper because she is an angry person. And Alex Trebek knows all the answers on Jeopardy! because he’s a really smart guy.

Which, of course, might be true, but then again, how much of what you do each day really says something about who you are—about what your personality or character is like? When we look at our own behavior, we perceive that much of what we do each day, the nuts and bolts of living, is more or less what anyone would do under similar circumstances. We are late to meetings because we get caught up in work, lose track of time, or get stuck in traffic. We lose our tempers because something frustrating or stressful has happened, or we’ve dropped something on our toe. And we’d look smart, too, if we got all the answers to tough trivia questions printed out for us on little cards.*

The recognition that correspondence is a bias, rather than an accurate way to draw conclusions about other people’s behavior, is, as Gilbert writes, “predicated on the sober insight that most of what people do says very little about them.”5 And that insight is certainly counterintuitive. Frankly it’s also more than a little unpleasant to think about. After all, we human beings have a strong desire to see ourselves as both unique individuals and as masters of our own fate. The idea that most of what we do, most of the time, is what anyone would do under the same circumstances undermines both our uniqueness and our sense of personal control. It’s not surprising, then, that this bias is so pervasive—even though it leads our perception astray.

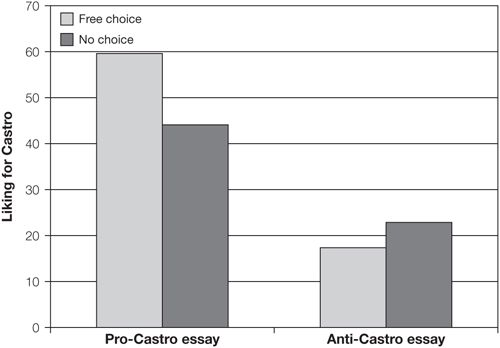

The most famous example of correspondence bias is perhaps the groundbreaking work of psychologists Edward Jones and Victor Harris.6 It was 1967, a mere five years after the Cuban missile crisis, and a time when Fidel Castro was a deeply unpopular figure across the United States. Jones and Davis gave groups of college students a short essay to read about Castro. One group was given an essay that argued firmly in favor of Castro and his policies, and the other was given a screed against them. Half of each group was told the essay had been freely written by an anonymous fellow college student, while the other half was told that the instructor had assigned the position the student was to take. After reading the essay, participants in the study were asked to estimate the author’s true views, on a scale from 0 to 100 (where 0 is a deep hatred and 100 is a profound love of Castro), how much the author personally liked Castro.

In 1967, if I knew nothing at all about your view of Castro, my best bet would be to guess that you didn’t like Castro—that was, after all, the norm. So my guess would be on the low end of the scale—perhaps a 20. And logically speaking, if you were required to write an essay advocating a particular viewpoint (something I remember having to do quite a few times in high school), then the fact that you wrote the essay in question would tell me nothing about your actual views. So obviously, I wouldn’t use that essay as an indicator of your actual views, right?

Wrong. Chances are I would. As you can see from figure 3-2, participants in the free-choice condition quite logically concluded that freely written pro-Castro essays indicated a liking for Castro (with an average rating around 60), while freely written anti-Castro essays indicated a dislike (with an average just below 20). But here’s where it gets strange and disturbing—participants in the no-choice condition still thought pro-Castro essays indicated a liking for Castro (44!). Not as much as freely chosen essays did, but way more than no-choice anti-Castro essays (23).

FIGURE 3-2

Does this essay writer actually like Fidel Castro?

Even when told that the opinion in an essay was assigned, readers assumed it reflected the writer’s real feelings about Castro.

Source: Edward Jones and Victor Harris, 1967.

Again, this is one of those things worth taking a minute to really process. There are all kinds of things each of us has to do each day because we have very little choice. Parents have to leave work when a child gets sick, regardless of how committed they are to their jobs. Managers have to cut positions or pass over for promotion people who deserve it, no matter how devoted the managers are to the members of their team, because of financial constraints or edicts from above. Millions of people who have lost their jobs remain unemployed months—sometimes even years—later, despite doing everything in their power to seek employment. And yet, working parents, particularly working mothers, are routinely perceived as less committed to their careers, managers are frequently blamed for organizational practices that are beyond their control, and the unemployed have a harder time getting hired than someone who already has a job.

In Phase 1, we simply do not consider the situational forces that affect—and sometimes completely control—someone’s behavior. We do not take context into account. That’s correspondence bias.

When you think about it, you begin to realize how little we actually know about other people—how much of our behaviors are driven by context, by common norms and preferences. And how few of our behaviors really say anything about our unique, individual selves. We are much harder to know than we realize or than Phase 1 perception would lead anyone to believe.

Just as people in pre–Phase 1 seem to naturally describe behaviors in terms of a person’s intentions (i.e., what the person was trying to do), in Phase 1, we seem to naturally describe people in terms of their traits—like smart, funny, creative, dishonest, and introverted. Traits end up playing a big role in our mental representations of one another, too. Chances are good that if I asked you to tell me about your spouse, your boss, or anyone else you know well, you would start rattling off a list of trait terms, rather than talking about their goals, beliefs, hobbies, or the groups to which they belong. Not that you won’t do any of the latter—but in general, when psychologists like myself ask people for descriptions of others, traits are what we get.

Of course, as famed psychologist Walter Mischel pointed out long ago, people don’t really have traits—if what you mean by trait is that people have stable and predictable tendencies to behave in certain ways all the time. Think about it—are extroverts always extroverted? Sure, they may be more gregarious and talkative than others, but probably only in certain situations. Some, for instance, may be extroverted (or clever, funny, warm, or engaging) with their friends, but less so with work colleagues or strangers.

True story: I know a man who met several of his late father’s coworkers for the first time at the father’s funeral. The son had always known his father to be an introverted, aloof sort of man—one who had barely spoken at home, unless it was to express criticism or complaint. So the son was completely taken aback to learn that his father—according to his colleagues—had been the life of the party, known for his terrific sense of humor and good nature. The son even considered—briefly—asking them if they were sure they had come to the right funeral.

The example is a clear case of someone’s displaying two sets of behaviors, associated with different sets of traits, in different settings. Such variability in behavior is the norm, not the exception, as years of research by Mischel and others have shown. A person’s “typical” behavior will change as a function of where he or she is, whom the person is with, and what he or she is trying to do. This, of course, is one of the reasons it’s relatively easy for two people to have very different impressions of you, depending on the situations they see you in.

The problem with all this Phase 1 thinking in terms of traits, though, is that it leads us to (wrongly) make assumptions we don’t even realize we’re making and to expect someone’s behavior to be more stable and predictable than it ever really is.

In Phase 1, our cognitive miser is running the show. It’s content to get the gist of things—to do the bare minimum. And to save itself time and effort, it relies on mental shortcuts and heuristics. These rules of thumb include the biases covered in chapter 2:

People who are similar to me in one way are probably similar to me in other ways.

People who have one good quality probably have lots of other ones.

People who are [black, Asian, women, poor, liberal, Muslim, Southern, investment bankers, etc.] are usually [trait].

We almost never even realize we are using assumptions like these to guide our perception, to make sense of someone else’s behavior. If I asked you if you even believe any of the above statements to be generally true, you would probably say no. But research shows that people don’t need to believe stereotypes and heuristics to use them—because recognizing that a stereotype or some other heuristic is wrong or inappropriate, and therefore shouldn’t factor into your view of someone, is really a Phase 2 thing (and we’re not there yet). In Phase 1, biases, assumptions, and rules of thumb run the show—influencing the impressions other people make on you in mere fractions of a second.

Of course, the fact that people are unknowingly operating on stereotypes and biases has real costs. Every once in a while a study comes along that illustrates these costs with shocking clarity, and for me one of the most compelling is the work of economists Marianne Bertrand of the University of Chicago and Sendhil Mullainathan of Massachusetts Institute of Technology. These researchers sent fake résumés in response to real help-wanted ads that had been posted in Boston and Chicago. They were interested in seeing how variations in the résumés would influence whether the applicant would be called back for an interview. So they manipulated the applicant’s experience—the better-qualified applicants had more experience, fewer holes in their employment history, and a slightly higher education level. The researchers also varied the names of the applicants to give the impression that the applicant was either probably white (e.g., Emily Walsh and Greg Baker) or probably African American (e.g., Lakisha Washington and Jamal Jones).7

After sending out well over a thousand résumés, they discovered that white-sounding applicants received one call back for every ten résumés sent, while African-American-sounding applicants with the same experience received only one call in fifteen. Further analysis revealed that in order for an African American to have the same odds of getting the job as a white applicant, he or she would need an additional eight years of experience.

Did the people who screened these applicants knowingly discriminate? Did they think to themselves, I’d prefer not to hire someone black? It’s tempting to think so—particularly when you are regularly on the receiving end of this sort of discrimination. But the research suggests that in fact, the vast majority of these screeners had no idea that negative stereotypes about blacks—ones the screeners may not even believe—were creeping into their Phase 1 perception and skewing their assessments of the applicants. Biases often act in very subtle ways, altering the way we interpret information without our ever realizing it.

For instance, imagine a résumé showing that the applicant has had three jobs in two years. What does a piece of information like that mean? When Emily Walsh’s résumé shows that she’s had three jobs in two years, the information is likely to be interpreted more benignly—perhaps as evidence that Emily is trying to find a job that provides the right fit, or even as a sign that she’s too hardworking to rest on her laurels. On the other hand, Lakisha Washington’s three jobs in two years—thanks to Phase 1 bias from a negative stereotype—is more likely to be seen as indicating a lack of commitment or a poor work ethic.

We can sum this all up with a fairly simple rule. In Phase 1, the perceivers see what they expect to see, even when they don’t consciously know what they are expecting.

Outrageous? Infuriating? Utterly unfair? Yes, absolutely, all of those things. And the worst part is that it is happening all the time—to every person who is a member of a stigmatized group, to every person who has previously made a bad impression or who has a past he or she would like to leave behind, and to you, too—when perception doesn’t get to Phase 2.

Phase 2 of Perception

He had all the outward trappings of an extraordinarily successful man—a penthouse in Manhattan, a yacht, an enviable art collection, prominent philanthropy. His brokerage had offices in New York and London. He flew by private jet to his homes in Montauk, Palm Beach, and Cap d’Antibes, France. A well-respected figure on Wall Street who once served as chairman of the NASDAQ stock exchange, he was also known to treat his employees like family.8 He was trusted by banks, hedge funds, asset management firms, pension funds, and dozens of charitable institutions to invest billions of dollars of their money.

In fact, his reputation was such that you were considered fortunate if he would even take your money—with his record of providing clients with consistently high returns, he could afford to be selective. One such fortunate client was Elie Wiesel, the Nobel Peace Prize winner and Holocaust survivor. Before investing, Wiesel met with this man over dinner and was so impressed by his philanthropy and his views on ethics and education that he placed all of his own life savings and a third of his charitable foundation’s endowment in the man’s hands.

This man was, of course, Bernie Madoff—perpetrator of the largest Ponzi scheme in recorded history and almost certainly a profound psychopath. Wiesel, who lost everything he had invested with Madoff, would later call him a “thief, scoundrel, criminal,” a “swindler,” and “evil”—this from a man who knows something about what evil looks like. And yet, neither Wiesel nor Madoff’s other victims saw any trace of these qualities until it was too late.

. . .

One of the most troubling findings in all of psychology has to be the fact that narcissists and psychopaths often make really good first impressions. Phase 2 exists to help the rest of us get past those impressions and learn what other people are actually like.

Generally speaking, in Phase 2, the perceiver wonders whether your behavior might have been caused by something about the situation you are in—something circumstantial, something that would affect others the same way. The person questions his or her own reasoning, trying to detect bias in the conclusions reached. As Gilbert puts it, “the conscious observer trails the parade, cleaning up after the elephants, following, fixing, and occasionally stepping in the conclusions that his mind seems so naturally to produce.”*

Phase 2 is often called the correction phase—it’s difficult, effortful, and not at all automatic. The perceiver has to have the mental energy, time, and motivation to enter it—if any of those elements are missing, the perceiver will just stick with the impression he or she formed during Phase 1. Often, it takes something really attention-grabbing to push us into it—something like our financial adviser’s stealing all our money and then getting indicted. And of course by that time, it’s too late.

That’s not to say that people never enter Phase 2 before disaster happens. Remember the Jones and Harris Castro essay study that revealed the remarkable power of correspondence bias? Years after the study was conducted, Gilbert carefully reviewed it (along with similar studies) and noted that there was often much less agreement among perceivers when essays were assigned as opposed to freely written. While the majority of people stuck with the Phase 1 conclusion (“He wrote an essay praising Castro, so he likes Castro”), at least some of the observers took the situation into account, realizing that an assigned essay is not much of a window into someone’s true views. These people had gone into Phase 2—for whatever reason, they were willing and able to weigh all the evidence to judge the writer accurately and fairly.

Unfortunately, we need to consider these admirable perceivers something like the exception that proves the rule. Yes, people can be accurate about you. But usually, they’re not.

Most people assume, at least implicitly, that the use of biases to judge other people’s behavior is motivated by prejudice. We want to think well or badly of people in a particular group, so we use the stereotype to justify it. But research over the last few decades has shown that humans are simply unable to enter Phase 2 and treat everyone as an individual 100 percent of the time. And some situations are harder than others. For instance, people stereotype more when they are solving complex problems, when they are stressed, when they are in bad moods, and even according to their daily circadian rhythms. Research by psychologist Galen Bodenhausen of the Kellogg School of Management shows that “morning people”—those who feel in top form in the first half of the day—are more likely to use stereotypes in their judgments of others in the afternoon. Those of us who are “evening people,” on the other hand, are more likely to use stereotypes right after breakfast.9

The work of stereotyping expert Patricia Devine finds that relevant stereotypes about a target tend to be automatically activated in Phase 1, but that in Phase 2 (if you can get there), perceivers can judge the appropriateness of using stereotypes to guide their judgment.10 Importantly, Devine’s work has shown that in Phase 1, stereotypes become activated even when they aren’t endorsed. In other words, even if I think that stereotypes based on gender, race, or anything else are offensive nonsense, as long as I know the stereotype, it will activate in my mind in Phase 1. And as long as a stereotype is active, it can exert influence.

And so, to communicate effectively—to come across the way you intend to in trying to make and maintain good impressions—you will need to really focus on sending the right signals at Phase 1. Getting things right at Phase 1 is by far the easier, and therefore preferable, option. And now that you know the kinds of assumptions perceivers tend to make in Phase 1, you can use that knowledge to your advantage and choose your words and actions accordingly.

But to truly master the art and science of perception, you need to understand that perceivers aren’t just trying to form an impression of you. Often, they have an agenda. They are trying to figure out whether they can trust you. Or they are trying to maintain their position of power or their self-esteem. Each of these agendas warps perception in its own unique way, creating a kind of lens through which you are seen. If you understand how the major lenses of trust, power, and ego warp Phase 1 perception, you have an even better chance of coming across as you’d like to. Part II helps you understand these lenses.

* For years, Saturday Night Live did a hilarious spoof of Jeopardy!, in which a profoundly hostile and uncooperative “Sean Connery” (played by Darryl Hammond), along with a series of brainless celebrities, tortured Will Ferrell’s “Alex Trebek.” In one episode, Connery angrily pointed out that Trebek wasn’t really so smart, because he “was reading the answers off cards.” This was the inspiration for my Trebek example, because at that moment, I remember thinking, “Hang on. I’ve been making that assumption, too!”

* As a general rule, academic writing is awful—and it’s almost never funny (at least, not intentionally). Dan Gilbert is the exception that proves the rule. His chapter on ordinary personology in the Handbook of Social Psychology is comprehensive, insightful, and hilarious. If you want to learn more about this topic, see D. T. Gilbert, “Ordinary Personology,” in Handbook of Social Psychology, vol. 2, ed. S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, and G. Lindzey (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998).