Co-Creating the Partnership

- how to create a safe coaching space between you and your client

- how to speak “the language of coaching” and how it differs from everyday workplace conversation

- the three levels of listening and techniques to perfect your listening approach

- the balance between inquiry and advocacy

- the top 10 dialogue techniques for successful coaching

Introduction: Raj’s Case

Pamela is a new coach, and she is preparing for her next coaching meeting with Raj, a rather difficult manager. Raj has issues with control and micromanaging. Wanting a bit of assistance, Pamela approaches a more seasoned coach, Tyrone, and asks for some tips. Pamela knows that the use of dialogue techniques is paramount in guiding the coaching process, establishing trust, and creating a safe space for coaching to happen. Tyrone reminds Pamela to listen actively and ask powerful questions that will guide Raj toward self-discovery. Pamela jots down a few meaningful questions:

- What are your goals as a manager?

- How would you describe your management style?

- What do you gain by managing the way you do?

- What other methods or styles might you try when managing people?

- How would you feel if your boss was always looking over your shoulder? What kind of message would this indicate to you?

- What might happen if you delegated more work and empowered your staff to do more on their own?

Tyrone also suggested that Pamela help Raj step back and gain perspective of his situation. In this way, it might be easier for Raj to see a disconnect between what he wants to achieve versus what is actually happening. Pamela thought carefully about this. Raj believes that micromanaging is the best way to manage. Unfortunately, the actual results in his department are low morale and decreasing productivity. Pamela realizes that Raj is in a vicious cycle and has set up his own self-fulfilling prophecy: The more he micromanages, the more he gets what he doesn’t want. Pamela decides she needs to help Raj paint a picture of an alternative way of going about his role and redefine his underlying beliefs and actions to achieve a more positive set of results.

Thankful for Tyrone’s assistance, Pamela thinks through other dialogue techniques she can use. She decides to kick off the next meeting with Raj by putting his situation in context, reminding him that his dilemma is common among new managers, and pointing out that he has many skills he can build on to get closer to his goals. She plans to demonstrate support, yet raise thoughtful concerns about consequences and alternative actions. She also intends to tell the story of two managers from other organizations who had similar problems and how they were able to adopt more successful approaches. And lastly, she underlined Tyrone’s key advice: Ask powerful questions!

Pamela’s planning of the upcoming coaching meeting demonstrates a very important ingredient of successful coaching: You can’t wing it and say whatever comes to mind! Choosing appropriate dialogue to create a supportive environment and guide the client toward growth takes thought and practice. In this scenario, Pamela concentrates on active listening, putting issues in context, asking powerful questions, and sensitively raising concerns. Such dialogue techniques make up the language of coaching and the major skill set that coaches need to practice to co-create a coaching partnership.

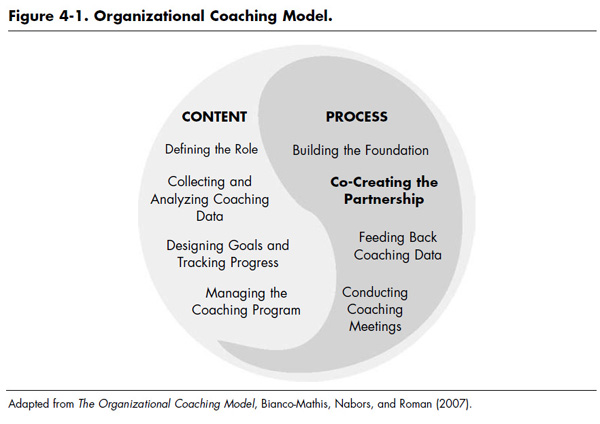

At all times, the individual, team, or organization being coached needs to feel supported and safe. This is best done through the use of dialogue skills that build trust, understanding, awareness, and self-discovery. If this is not established, feedback will fall on deaf ears and action planning will be merely a game that leads to inaction and no change. The entire coaching process pivots on the coach’s expertise in saying and asking the right things, at the right time, in the right way. This requires expertise in a series of dialogue skills that must be practiced and honed. The result will be the creation of a coaching environment where clients feel safe enough to embark on a path of continuous improvement. Consequently, co-creating the partnership—dialogue that is continually practiced throughout the coaching relationship—is shown as a process step in figure 4-1.

So let’s begin!

Coaching Space

Coaches create a space of exploration, learning, safety, and discovery based on intense dialogue. This differs from training or reading a book. Coaching is based on fostering an interpersonal space for reflection, questioning, enabling, authenticity, and insight.

To achieve a coaching space, coaches must communicate powerfully, help others create desired outcomes, and hold relationships based on honesty, acceptance, and accountability (Bianco-Mathis, Nabors, and Roman 2002). In our initial scenario, Pamela was focusing on making Raj feel comfortable so he could consider his own behavior without judgment and safely move toward alternative behaviors.

By fostering a safe coaching space, according to Hargrove (1995), you can

- make it possible for people to take action within areas where they are most stuck or ineffective

- transform people’s views of themselves and help them move from stuck places to effective action

- help people act even when the outcome is uncertain

- assist individuals, teams, and organizations in letting go of the psychological investments in present belief systems and test assumptions

- create practice field assignments that are both challenging and supporting

- inspire people and help them recognize the previously unseen possibilities that lie embedded in their existing circumstances.

Perhaps the best way to experience this is to think of a time at work when you felt safe and supported. What was being said or done that contributed to those feelings? What results were you able to accomplish? What were the benefits of operating in this kind of environment? Now think about coaching someone. How can you create such a space with your coaching clients? What kinds of things might you say? This needs to be your goal for every coaching meeting. Practicing the techniques outlined in the rest of this chapter will help you achieve this goal.

The Language of Coaching

The language of coaching involves using powerful questions, getting behind the reasoning of others, listening intensely, and using dialogue tools that empower others to reflect and grow.

Getting familiar with and becoming proficient in the language of coaching requires the same practice and mindfulness as learning a foreign language. You see in your mind what you want to say in your native tongue, you transfer your thoughts to the comparable words in the foreign language, and you then force your brain to produce the newly patterned words. Over time, your brain makes the switch more quickly. With intense practice and immersion in the new language, your brain begins to think in the foreign language as easily as it does in your native tongue. This is the same mind rewiring that you need to master in learning and practicing dialogue techniques. The reason for this is that you must control your natural responses and respond in ways that best assist the individual, team, or organization you are coaching—not what you might want to say or would find yourself saying within a non-coaching situation. Even though you might want to express yourself in a certain way, that certain way might not foster growth or understanding for the client. In fact, you might foster just the opposite—defensiveness, fear, or anger. Consequently, you need to flip the switch in your brain and use a more appropriate dialogue approach.

To understand the concept of dialogue more fully, it is necessary to distinguish it from other forms of communication. Dialogue is different from discussion. As shown in table 4-1, dialogue supports a coaching environment, whereas discussion hinders it. When you are justifying or persuading—something done almost unconsciously—you are using labels, causing defensiveness, and blocking learning. This creates a zone of hostility, resistance, and miscommunication. In contrast, dialogue invites reciprocal understanding and a higher level of meaning. This leads to insight and more positive action.

Three main skill sets practiced within dialogue are listening, inquiry, and advocacy.

Listening

In their book Co-Active Coaching, Whitworth et al. describe three levels of listening that are commonly used in the world of coaching (1998). These levels go far beyond nonverbal behaviors.

The first level is internal listening. If you use this level when coaching, you will only listen in terms of your own experience and needs. You’ll listen to the words to formulate your own opinion, give advice, or offer your own story. Such an approach does not foster a coaching space and uses discussion instead of dialogue. Here are some examples of this ineffective approach:

- “You shouldn’t have done that. You should have just walked out of the meeting.”

- “I can top that. Once, my boss told me to write my own performance appraisal, so I gave myself an outstanding.”

The second level is focused listening. When you use this approach, you concentrate on the other person, listening to understand. You demonstrate listening through acknowledging, asking questions, clarifying, reflecting, probing, supporting, and problem solving. This better incorporates dialogue and more active listening. The focus is on the client, not you. Note the more positive effect of the following examples:

Table 4-1. Discussion versus Dialogue.

| Discussion | Dialogue |

| A form of verbal communication based on justifying, defending assumptions, persuading, selling, and telling. | A form of verbal communication based on inquiring into assumptions, learning through inquiry and disclosure, and creating shared meanings. |

| Example: “Just go to your manager and tell her that she is not giving enough feedback on projects.” | Example: “I understand what you mean about not giving you enough feedback. That must be very frustrating given that you want to do a good job. I’m wondering what would happen if you shared your concerns with your manager? How might you go about such a dialogue?” |

- “So, Mary, you feel upset because Joan left without helping you with the data input?”

- “Help me understand. You believe this was inappropriate because the director asked you to develop the report and not Tamika?”

- “I can understand why you might feel discounted when your boss left without commenting on your presentation. How else can you explain his behavior?”

- “Let me see if I understand the dynamics at play here. You believe that the report should be done immediately, and the accounting department believes it can wait until after the holidays. Is this correct?”

- “Interesting dilemma. What options do you see? Might there be a way to satisfy everyone’s needs?”

The last level, global listening, is the most sophisticated and embodies the essence of coaching. It includes all of the elements of level two and adds the dimension of observing; stating observations; making analogies; using metaphors; making connections to other ideas and patterns within the situation; and noting subtle changes in the speaker’s tone, attitude, or expressions. This adds richness to your observations and guides the client toward action. By noting patterns and connections, the coach can surface insights that clients have not been able to discover on their own. This, in turn, leads to more focused direction, actions, and change. Note the following examples:

- “I’ve noticed that your voice has gotten much lower when talking about that incident. Why is that so?”

- “Your reaction to this decision you have to make reminds me of a person on an elevator—the elevator has stopped at your floor, the doors have opened, you raise your foot to step out, then you freeze, unable to move forward. What do you think?”

- “I might be wrong here, but let me know what you think about this: It sounds like you are scared of John. Might that be true on some level?”

Like all methods and styles of communication, it is not helpful to use the same approach in every situation. With practice, you will learn how to mindfully choose and use different listening levels and techniques to balance your approach and effectiveness.

A good exercise that you can do is to engage in a coaching conversation where you, as the listener, ask only powerful questions. Do not allow yourself to make comments or share an idea or thought. Just stick to questions. This exercise should force you to listen more deeply and intently to the other person because you have to use the information you just heard to formulate your next question—instead of using that time to formulate your own comeback or answer.

Coaches who have tried this exercise explain that it is hard to do. They have to slow down their thinking, creatively design questions to carry the conversation toward meaningful action, concentrate on what is exactly being said or implied, and form questions that guide the clients toward their own insights instead of blurting them out. Clients who partake in this exercise claim that they feel really listened to, realize that the questions are meaningful and require a thoughtful response, and find themselves formulating insights on their own without being told or pushed.

Inquiry

The second skill set is inquiry. You just saw how listening includes the use of powerful questions. Then what is inquiry? Inquiry definitely involves the asking of questions—but with a specific purpose in mind. Inquiry requires that you communicate from a place of genuine curiosity. It involves the asking of questions to discover the reasoning behind what was done or said, before assuming. Some inquiry questions include the following:

- “How did you come to that conclusion?”

- “How do you see this situation?”

- “What information did you consider when you came to that conclusion?”

- “Help me understand your thinking here.”

Advocacy

The last skill set, advocacy, works hand-in-hand with inquiry. The purpose of advocacy is to share your thoughts and make suggestions by explaining the reasoning behind them. Once you offer your ideas with reasoning, you then ask for input to test your reasoning and foster inclusion and partnership. The following are some advocacy comments along with inquiry questions:

- “I came to this conclusion because you told me you didn’t want to do that kind of work. Have you now expanded your career goals so that you might consider this option?”

- “I’m making this assumption based on the fact that you want to improve your presentation skills. Will this opportunity allow that to happen, or is something else going on here?”

- “Given the way you just snapped at me when I offered you that piece of feedback, I’m assuming that this is a sensitive topic for you. Am I correct?”

- “I infer from your tone that you are angry about the incident with your colleague. Am I making an accurate inference?”

- “I see this as a situation where your department and the other department have conflicting goals. How do you see the situation?”

- “Let me share with you a possible approach. After you hear it, let me know if you think it might work for you.”

The goal is to balance inquiry and advocacy. It is not always 50-50. You want to ask questions in such a way that you get to the reasoning behind an action or thought— yours or your client’s. When you have a need to share a piece of information, concern, or alternative perspective, do so by explaining your reasoning and then inviting the client back into the conversation: What do you think? What might happen if you tried this? How do my thoughts support what has already been said? In this way, the conversation remains in dialogue and does not fall into discussion, telling, or judging. It is an ongoing partnership, leading to discovery and growth.

More Dialogue Techniques

As you master listening, inquiry, and advocacy, you will find yourself noticing and acquiring more and more tools. Ten further dialogue tools are offered in table 4-2. From this point forward, mastering dialogue needs to become a daily activity, just like practicing a new language. A fun practice exercise is to choose one new dialogue technique per week and continually use it throughout your work. In this way, you will train your brain and dialogue will eventually become your preferred way of speaking, not a conscious struggle.

Dialogue Practice

As pointed out earlier, you must practice dialogue as if it were a new language. Train your ear and hardwire your brain. Read through the following dialogue scenario. Read it aloud so you actually verbalize and hear the techniques being used. Note the effect each technique has on the coaching taking place.

Mary Andrews is a customer care advisor and internal coach. She is coaching Bob Wilson, a call center representative, in the claims loss taking unit. They are working on three goals for Bob: using more open-ended questions, expressing appreciation, and avoiding asking customers to repeat information. This is a transcript of their most recent meeting.

Mary: Well, Bob, it looks like you are asking more open-ended questions during your calls. When I listened to six of your calls from last week, I noticed that you asked the caller an average of 10 questions per call compared to the four questions per call you had been averaging. [points out positive behavior]

Table 4-2. Dialogue Techniques.

| Dialogue Techniques | Examples |

1. Acknowledge first, then raise questions and concerns. |

“You can certainly try that approach. It will allow you to practice speaking up more in meetings. There are a few concerns we should consider. Let me share them with you and see what you think.” |

2. Put the message in context. Provide perspective. Prepare the listener |

“I’m going to share some feedback that may come as a surprise to you. It is different than what you have heard before, and I think it bears listening to because it comes from your peers.” |

3. Give an example, tell a story, or use an analogy. |

“Another approach you might use is something I saw being used in another department.” |

4. Put yourself in the other person’s shoes. |

“If I put myself in your shoes, I can see feeling a bit anxious right now.” |

5. Focus on the ultimate purpose. |

“Given that we all have our own departmental agendas, let’s try to focus on the best integrated solution.” |

6. Point out the positive, and explain why it is a positive. |

“That is an excellent strategy to use. You will be showing your support and also making your own needs clear.” |

7. Help to paint a picture. |

“That’s an interesting plan for how to conduct the new program. Paint me a picture of how you would implement that.” |

8. Use a problem-solving approach. |

“Though your personal preference differs with that of your boss, what are some options for meeting your mutual needs?” |

9. Play devil’s advocate. |

“If I were to play devil’s advocate, I could view that comment as more manipulative than helpful. Let me explain why.” |

10. Offer your ideas; don’t demand them. |

“Something you might think about is . . . ” |

Adapted from The Dialogue Deck, Bianco-Mathis, Nabors, and Roman (2007).

Bob: Thanks, Mary. I’m getting more comfortable with using those questions. The cards you gave me remind me to use the questions, and they help me to practice. [uses a job aid to assist practicing new behaviors]

Mary: Great. What progress are you making with your active listening and note taking? [asks for specific examples and does not talk in generalities]

Bob: To be honest, I’m not making the kind of progress I expected.

Mary: Oh? If I put myself in your shoes I can see where you might be a bit frustrated . . . and I think I hear that in your voice. Tell me more about that. [empathizes and asks for reasoning]

Bob: Yeah, you do. You know me. I want to see 100 percent across the board in my next technical assessment. I guess we should add patience to our list.

Mary: Let’s focus on our overall goal and notice what you are already doing and the progress you’ve already made. In the four weeks we’ve been working together, you’ve incorporated more questions in each call. This is bringing you closer to those higher performance scores. What’s happening with your active listening and note taking? What do you mean when you say you’re not making the kind of progress you expected? [focuses on overall goal, puts frustration in perspective by outlining progress, and asks for clarification and reasoning]

Bob: Well, I’ve been taking notes like we discussed during my calls. Remember, we thought that might help me cut down on the questions I was asking my customers when they had already given me the information. But sometimes I still get confused between entering the information in the system and taking notes on my pad and talking to the customer. I’m having trouble keeping everything straight. I feel more confused, not less. [uses another job aid—taking notes]

Mary: It sounds like our technique of note taking isn’t helping. Let’s think about what else we might try? [poses question to get client to think through possibilities—doesn’t give answers]

Bob: Like what?

Mary: That’s what we’re going to figure out. Think about a situation where you do a good job of listening and you accurately keep track of information provided. [doesn’t fall into the trap of providing an answer, but asks the client to think of another situation that might be helpful in this situation—an analogy, a transfer of skill sets from one situation to another]

Bob: Hmmm . . . well, I do a lot of home improvement projects and sometimes I attend how-to classes. I do a good job of following the instructions and steps, and then I can recall them when I’m working on my own project.

Mary: Okay. Think back to the last class you attended. How were you able to keep track of what the instructor was saying? [asks the client to paint a picture and specifically play out the actions]

Bob: Well, I was interested in the content because I was going to use it. I was focused on what the instructor was saying; my mind was 100 percent on him and what I was learning. I wasn’t distracted by my surroundings, and I wasn’t worried about what I had to say next. I asked a few clarifying questions when I needed more detail. I guess that’s about it. How does this help us with my clients?

Mary: Bob, you just painted a picture of you at your listening best. All we have to do is see how you can use those techniques and approaches in the call center. First, you said you were interested. How can you mentally get interested before each call? [notes the pictures in the head so the client can duplicate those actions in a new situation and uses the related story so it can provide insight to the present situation]

Bob: Well, my customers matter to me. I want to help them.

Mary: Okay. So how can you focus on that desire to serve your customers? [encourages the client to come up with new actions and helpful tips that he can readily adopt and apply]

Bob: Hmmm. I used to have a sticky note that said, “How can I serve you?” right in front of my station. I don’t know where it went.

Mary: I wonder, could we make a new one? [poses the idea as a question so the client makes the decision to act]

Bob: Sure, I can do that.

Mary: Okay. Next, how can you focus on the caller 100 percent with no distractions? [moves the thinking and brainstorming to the next step by posing another powerful question]

Bob: Well, now that we’re talking about this, I guess each call gives me the opportunity to learn what I need to know to help my customer. That should help me to pay attention.

Mary: Perfect. Let me ask, since you’ve been incorporating more questions into your conversations, how can that work for you in this process? [encourages the client to use the techniques in coaching to on-the-job situations through a powerful question]

Bob: If I’m focused on my customer, I don’t have to worry about what I have to say next. The questions will guide us through the process. And, if I need more information, I can ask a clarifying question.

Mary: Excellent. It sounds like we have a new plan to try. What do you think? [summarizes the progress by offering an insight and asking the client to respond to that insight]

Bob: You’re right. I’m excited. I never thought about the skills I use in real life being transferable to work. I think this can work.

Mary: Good. I think so, too. I’ll be looking forward to our next meeting and your update. [acknowledges agreement and a sense of moving forward]

This chapter has demonstrated the language of coaching—dialogue. It is through listening, inquiry, and advocacy that you create a safe space for the client to learn, discover, and grow. Through intense practice—like hitting hundreds of tennis balls or spending hours at the piano—you can rewire your brain so active listening and powerful questions become natural and easy for you to use. When you engage your clients in true dialogue, they will be able to reflect, face their learning challenges, and reach higher levels of success.

Moving Ideas to Action

Through conscious practice, you can rewire your brain so that the dialogue tools come to mind more readily. You can begin by using the application job aid in table 4-3. Think of a past conversation or upcoming conversation you need to have. Using the examples from table 4-2 as a guide, develop your own examples to fit your chosen conversation. Then give it a try in real time!

Table 4-3. Dialogue Skills in My Conversations.

| Dialogue Techniques | My Application Examples |

1. Put yourself in the other person’s shoes. |

|

2. Tell a story or use an analogy. |

|

3. Help to paint a picture. |

|

4. Play devil’s advocate. |

|

5. Focus on the ultimate purpose. |