Chapter 3. Why Is PCI Here?

Chances are if you picked up this book, you already know something about the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS); however, you might not have a full and clear picture of PCI DSS – both the standards and its regulatory regime – and why they are here. This chapter covers everything from the conception of the cardholder protection programs by the individual card brands to the founding of the PCI Security Standards Council (PCI SSC) and PCI DSS development. It also explains the reasons for PCI DSS arrival that are critical in understanding how to implement PCI DSS controls in your organization. Also, many of the questions people ask about PCI DSS and many of the misconceptions and myths about PCI have their origins in the history of the program, so it only makes sense that we start at the beginning.

What Is PCI and Who Must Comply?

First, “PCI” is not a government regulation or a law. 1 As you know, when people say “PCI,” they are actually referring to the PCI DSS, at the time of this writing, of version 1.2.1. However, to make things easy, we will continue to use the term PCI to identify the payment industry standard for card data security.

1PCI DSS or the elements of it have been adopted as actual law in at least two US states at the time of this writing. The State of Nevada explicitly called PCI DSS by reference and made it mandatory for some businesses operating in this state. The State of Minnesota has adopted select provisions of PCI DSS as a state law.

Unlike many other regulations, PCI DSS has a very simple and direct answer to a question “who must comply?” Despite its apparent simplicity, a lot of people have attempted to misunderstand it, which leads the authors to believe that most of such people had their own agenda. This always reminds us of a quote from Upton Sinclair, a noted American novelist, who said “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his job depends on not understanding it”[1]. So, PCI's answer to “who must comply?” is any organization that accepts payment cards or stores, processes, or transmits credit or debit card data must comply with the PCI DSS.

Note

PCI applies if your organization accepts, processes, stores, and transmits credit or debit card data.

It is very easy to understand the motivations for such broad applicability. It is clearly pointless to protect the card data only in a few select places; it needs to happen wherever and whenever the card data is present. This is where a thought might cross your mind as to why the data is present in so many places. A recent MasterCard presentation at a payment security conference presented a curious statistic that there are more than 200,000 locations where payment card data is stored in large amounts. Please hold that thought as it is a very important one to keep while reading this book. Without jumping too much ahead in our story, we'd say that in many cases, adjusting your business process to not touch the card data directly will save you from a lot of security and compliance (and not just PCI DSS compliance!) challenges!

In this book, we are primarily concerned with merchants and service providers. The merchants are pretty easy to identify – they are the companies that accept credit cards in exchange for goods or services. The PCI official definition of a merchant [2] states: “a merchant is defined as any entity that accepts payment cards bearing the logos of any five members of PCI SSC (American Express, Discover, JCB, MasterCard, or Visa) as payment for goods and services.” For example, a retail store that sells groceries for cash or credit cards is a merchant. An e-commerce site that sells electronic books is also a merchant.

However, when it comes to service providers, things get a bit trickier. PCI Council Glossary [3] states: “Business entity that is not a payment card brand member or a merchant directly involved in the processing, storage, transmission, and switching or transaction data and cardholder information or both. This also includes companies that provide services to merchants, services providers or members that control or could impact the security of cardholder data. Examples include managed service providers that provide managed firewalls, IDS and other services as well as hosting providers and other entities. Entities such as telecommunications companies that only provide communication links without access to the application layer of the communication link are excluded.”

A merchant can also be a service provider at the same time: “…a merchant that accepts payment cards as payment for goods and/or services can also be a service provider, if the services sold result in storing, processing, or transmitting cardholder data on behalf of other merchants or service providers”[2]. A more esoteric situation arises if a company accepts credit cards as a payment for services it provides to other merchants who also accept credit cards. In this case, such an entity is both a merchant and a service provider. For example, if you provide hosted shopping cart and processing services to merchants and accept payment cards, you would be both.

After those initial definitions, we will describe the whole payment ecosystem for the purposes of PCI DSS.

Electronic Card Payment Ecosystem

Before we go into detail on PCI compliance, we'd like to paint a quick picture of an entire payment card “ecosystem” (see Fig. 3.1).

Figure 3.1 shows all the entities in payment card “game”:

■ Cardholder, a person holding a credit or debit card

■ Merchant, who sells goods and services and accepts cards

■ Service provider (sometimes Merchant Service Provider (MSP) or Independent Sales Organization (ISO), who provides all or some of the payment services for the merchant

■ Payment processor, which is a particular example of an MSP

■ Acquiring bank, which actually connects to a card brand network for payment processing and also has a contract for payment services with a merchant

■ Issues bank, which issues payment cards to consumers (who then become “card holders”)

■ Card brand, which is a particular payment “ecosystem” (called “association network”) with its own processors, acquirers, such as Visa, MasterCard, and Amex

The primary focus of PCI DSS requirements is on merchants and MSPs. This is understandable since this is exactly where most of the data is lost to malicious hackers. Whether TJX in 2005 to 2007 (45 or 90 million cards stolen, depending on the source) or Heartland Payment Systems in 2008 to 2009 (more than 100 million cards stolen), merchants, and service providers have let cards be stolen from them without incurring any of the costs to themselves and without having a motivation to improve their security even to low levels prescribed by PCI DSS. While the merchants were letting the card data “run away,” the issuing banks were replacing them at their own cost and incurring other costs as well. Thus, PCI DSS was born to restore the balance to the system by making sure that merchants and service providers took care of protecting the card data.

Goal of PCI DSS

In light of what is mentioned above, PCI DSS is here to reduce the risk of payment card transactions by motivating merchants and service providers to protect the card data. Whether this goal is worthy, whether there are other secondary goals, or even whether this goal is being achieved by a current version of the data security standard is irrelevant. What matters is that PCI is aimed at reducing the risk of transaction and it seeks to accomplish that by making merchants and service providers to pay attention to many key aspects of data security, from network security to system security, application security, and security awareness and policy. What is even more important, it encourages merchants to drop the data and conduct their business in a way that eliminates costly and risky data storage and on-site processing, whenever possible. Reduction of fraud is expected to be a natural result of such focus on security practices and technologies. One of the original PCI creators has also described PCI as the following: “the original intent was to design, implement, and manage a comprehensive, cost effective and reliable security effort”[4] and not a patchwork of security controls.

It is interesting to note that the “Ten Common Myths of PCI DSS” document from the PCI Council presents the six domains of PCI DSS as its goals [5]:

1. Build and maintain a secure network

2. Protect cardholder data

3. Maintain a vulnerability management program

4. Implement strong access control measures

5. Regularly monitor and test networks

6. Maintain an information security policy

While the above six domains can be seen as tactical goals while implementing PCI DSS, the strategic focus of PCI DSS is card data security, payment card risk reduction, and ultimately the reduction of fraud losses for merchants, banks, and card brands.

Overall, while motivating security improvements and reducing the risk of card fraud, PCI DSS serves an even higher goal of boosting consumer confidence in what is currently the predominant payment system – credit and debit cards. While we can debate whether cash is truly on the way out, the volume of card transactions is still increasing at an impressive 20 to 40 percent rate annually. If anything – whether malicious hackers, insiders, or any other threat – can hinder it, major implications to today's economy may be incurred. Thus, PCI DSS defends something even bigger than “bits and bytes” in computer systems, but the functioning of the economic system itself.

Applicability of PCI DSS

It is likely that the statements about accepting card data or processing, storing, and transmitting payment card data will likely sound tiresome by the time you are finished reading our book; it is worthwhile to remind you that PCI DSS applies to all organizations that do just that, and there are no exceptions. Our Chapter 15, “Myths and Misconceptions of PCI DSS” covers some of the common delusions and clarifies that the above PCI applicability is indeed the reality and not the myth.

While the applicability of PCI DSS to organizations that deal with card data is certain and all the DSS requirements apply, the question of validating or proving PCI compliance is a bit different. It differs for merchants and service providers; it also differs by card brand and by transaction volume.

First, there are different levels of merchants and service providers. Table 3.1 and Table 3.2 show the breakdown.

Note

Visa Canada levels may differ. Visa Europe is also a separate organization that has different rules. Discover and JCB do not classify merchants based on transaction volume. Contact your payment brand for more information while paying attention to your location.

Note

Visa Canada levels may differ. Visa Europe is also a separate organization that has different rules. Discover and JCB do not classify merchants based on transaction volume. Contact your payment brand for more information while paying attention to your location.

As we mentioned above, these levels exist for determining compliance validation that is discussed in the next section. The levels are also sometimes used by the card brands to determine which fines to impose upon the merchant for noncompliance.

PCI DSS in Depth

In the next section, we take a detailed look at PCI DSS standard, its entire regulatory regime, deadlines, as well as related security vendor certification programs.

Compliance Deadlines

Now that we touched upon the compliance basics, it is time to face the painful fact: all the PCI DSS compliance deadlines are in the past (See Table 3.3). This means that now is the time to be compliant. There are additional dates for various other related requirements (such as card brand dates for Payment Application Data Security Standard [PA-DSS] compliance), but all core PCI DSS dates have indeed passed.

Some of you recall receiving a letter from your company's bank or a business partner many years ago that had a target compliance date. Such letters are rare since the dates for PCI DSS compliances have actually passed. This date may or may not be aligned with the card brands' official dates. This is because the card brands may not have a direct relationship with you and are working through the business chain of acquiring banks. When in doubt, always follow the guidance of your legal department that has reviewed your contracts.

Thus, barring unusual circumstances, the effective compliance deadlines have long passed. Various predecessor versions of the PCI 1.2 standard had unique dates associated with them, so if your compliance efforts have not been aligned to the card brand programs, you are way behind the curve and will not likely get any sympathy from your bank.

As far as additional dates by card brands, please refer to the following resources:

■ Visa: http://usa.visa.com/merchants/risk_management/cisp_key_dates.html. This page includes dates such as “U.S. Level 1 Merchants Full PCI DSS Compliance Validation Deadline” (September 30, 2010 applies to new merchants) and “U.S. Level 2 Merchants Full PCI DSS Compliance Validation Deadline” (December 12, 2010 applies to new merchants as well).

■ MasterCard: www.mastercard.com/us/sdp/merchants/merchant_levels.html. This page includes recent change for merchant compliance validation for Level 2 merchants with an associated deadline of December 2010.

■ Discover: www.discovernetwork.com/fraudsecurity/disc.html. This page contains no additional deadlines but simply refers to the PCI Council site. All PCI requirements currently apply to all merchants.

■ American Express: www209.americanexpress.com/merchant/singlevoice/dsw/FrontServlet?request_type=dsw&pg_nm=home. This page also does not contain any additional deadlines; all PCI requirements currently apply to all merchants.

Compliance and Validation

As we mentioned before, depending on your company's merchant or service provider level, you will either need to go through an annual on-site PCI assessment by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA), or complete a Self-Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ) to validate compliance. In addition to this, you will have to present the results of the quarterly network perimeter scans that had to be performed by an approved scanning vendor (ASV).

In particular, while SAQ validates PCI compliance, there needs to be evidence that validates that the questions in the SAQ are answered truthfully.

When submitting a SAQ, it will have to be physically signed by an officer of your company. 2 At the present time, there is no court precedent for officer liability as a result of false attestation. However, industry speculation is that this person may be held accountable in a civil court, especially if he or she commits an act of perjury while certifying.

If you are planning on submitting a Report on Compliance (ROC) instead of the SAQ, you will need to follow the document template outlined in the PCI DSS Security Audit Procedures document. After the SAQ has been filled out or the ROC has been completed, it must be sent along with all the necessary evidence and validation documentation to the acquirer, to the business partner, or to the card brand directly. It depends on who requested the compliance validation in the first place.

It is a common misconception that the compliance requirements vary among the different levels. Both merchants and service providers must comply with the entire DSS, regardless of the level. Only verification processes and reporting vary. Visa Web site explains it like this: “In addition to adhering to the PCI DSS, compliance validation is required for all service providers”[6].

Note

Discover and JCB handle merchant PCI compliance validation differently. Contact the payment brand for more information.

The validation mechanisms, as of the time of this writing, are given in Table 3.4.

Further, the exact scope of PCI DSS validation differs based on the exact way the organization interfaces with card data. Specifically, quoting from the PCI Council Web site, the circumstances that affect what sections of the SAQ the merchant should complete for validation are provided in Table 3.5.

So, to summarize, the exact scope of any one's PCI DSS validation depends on the following:

■ Merchant or service provider status

■ Transaction volume

■ Card brand

■ The method of accepting cards and interacting with card data

Note

Although American Express and Visa allow Level 1 merchants to have their PCI compliance validated by the merchant's internal audit group, MasterCard does not explicitly allow this. If this affects your company, contact MasterCard for clarification.

Warning

Don't let yourself become complacent. If you are a Level 4 merchant across the board and are not required to do anything to validate your compliance with PCI DSS, remember, by accepting even one card per year, you are required to comply with PCI DSS. Many Level 4 merchants end up in big trouble when they realize they had to comply with PCI DSS regardless of their validation requirements. In addition, due to different validation levels across major card brands, their situation in regards to PCI compliance may be much worse.

Also, it is important to note that the specifics of validation requirement might change. For example, in June 2009, MasterCard announced that Level 2 merchant will not need to be validated via an on-site assessment. Expect validation requirements to become stricter in the future.

It is worthwhile to note that it is possible for a company to be a merchant and a service provider at the same time. If this is the case, the circumstances should be noted, and the compliance must be validated at the highest level. In other words, if a company is a Level 3 merchant and a Level 2 service provider, the compliance verification activities should adhere to the requirements for a Level 2 service provider.

One of the notable PCI assessors, Walt Conway, relates the following educational story about merchant and provider validation:

“My favorite is when the vendor replies that they are compliant as a Level 3 (or 2 or whatever) merchant. That response is completely irrelevant and inexcusably misleading. That they are compliant as a merchant is meaningless to you when you use them as a service provider. They can self-assess as a merchant – they cannot as a Level 1 service provider. That extra step is meant to protect you. If you get that kind of reply, you are likely dealing with an over-eager and/or ill-informed sales rep…ask to talk to an adult”[7].

History of PCI DSS

To better understand the PCI DSS role, its motivation and its future, it is useful to look at its origins and history.

PCI DSS has evolved from the efforts of several card brands. In the 1990s, the card brands developed various standards to improve the security of sensitive information. In the case of Visa, different regions came up with different standards since European countries and Canada were subject to different standards than the US. In June 2001, Visa launched the Cardholder Information Security Program (CISP). The CISP Security Audit Procedures document version 1.0 was the granddaddy of PCI DSS. These audit procedures went through several iterations and made it to version 2.3 in March 2004. At this time, Visa was already collaborating with MasterCard. Their agreement was that merchants and service providers would undergo annual compliance validation according to Visa's CISP Security Audit Procedures and would follow MasterCard's rules for vulnerability scanning. Visa maintained the list of approved assessors and MasterCard maintained the list of ASVs.

This collaborative relationship had a number of problems. The lists of approved vendors were not well-maintained, and there was no clear way for security vendors to get added to the list of each particular card brand. Also, the program was not endorsed by all card brand divisions. Other brands such as Discover, American Express, and JCB were running their own programs as well. The merchants and service providers in many cases had to undergo several independent assessments by different “certified” assessors just to prove compliance to each brand, which was clearly costing too much and not resulting in quality assessments either. For that and many other reasons, all card brands came together and created the PCI DSS 1.0, which gave us the concept of PCI compliance.

Unfortunately, the issue of ownership still was not fully addressed, and a year later, the PCI Security Standards Council was founded, and its Web site www.pcisecuritystandards.org was created. Comprised of American Express, Discover Financial Services, JCB, MasterCard Worldwide, and Visa International, PCI Council (as it came to be known) maintains the ownership of the DSS, most of the approved vendor lists, training programs, and so on. There are still exceptions, as the list of approved payment application assessors only recently has been transferred from Visa PABP to PCI Councils' PA-DSS. Also, incident forensics is still handled by the card brands themselves and not by the PCI Council. For example, Visa still runs its Qualified Incident Response Assessor (QIRA) certification.

Note

Visa QIRA can be found on Visa Web site at http://usa.visa.com/download/merchants/cisp_qualified_cisp_incident_response_assessors_list.pdf.

Even today, each card brand/region still maintains its own security program beyond PCI. These programs go beyond the data protection charter of PCI and include activities such as fraud prevention. The information on such programs can be found in Table 3.6. In certain cases, PCI ROC needs to be submitted to each card brand's program office separately.

| Card Brand | Additional Program Information |

|---|---|

| American Express | Web site: www.americanexpress.com/datasecurity. E-mail: [email protected] |

| Discover | Web site: www.discovernetwork.com/resources/data/data_security.html. E-mail: [email protected] |

| JCB | Web site: www.jcb-global.com/english/pci/index.html. E-mail: [email protected] |

| MasterCard | Web site: www.mastercard.com/sdp. E-mail: [email protected] |

| Visa USA | Web site: www.visa.com/cisp. E-mail: [email protected] |

| Visa Canada | Web site: www.visa.ca/ais |

PCI Council

PCI Council or, fully, PCI Security Standards Council or PCI SSC, describes itself as “an open global forum for the ongoing development, enhancement, storage, dissemination, and implementation of security standards for account data protection”[8].

PCI Council charter provides oversight to the development of PCI security standards (including PCI DSS, PA-DSS, and PIN Entry Devices [PED]) on a global basis. It formalizes many processes that existed informally within the card brands. PCI Council published the updated DSS, at the time of this writing at version 1.2.1, which is accepted by all brands and international regions; it also updates the supporting documents such as “PCI Quick Reference Guide” and recent “Prioritized Approach for DSS 1.2” (March 2009) and “PCI SSC Wireless Guidelines” (July 2009) documents.

Version 1.2.1

The Council mission also includes maintaining two vendor certification programs for on-site assessments (QSA) and network scanning (ASV), which are covered in the next section. The lists of current QSAs and ASVs are located at the council Web site: www.pcisecuritystandards.org/qsa_asv/find_one.shtml. In addition, the Council also runs the so-called “QA programs” (quality assurance programs) for QSAs and ASVs. which are aimed at maintaining the integrity of site assessments and vulnerability scans.

PCI Council is technically an independent industry standards body, and its exact organizational chart is published on its Web site (www.pcisecuritystandards.org/about/organization.shtml). Yet, it remains a relatively small organization, primarily comprised of the employees of the brand members.

The industry immediately felt the positive impact of PCI Co. The merchants and service providers can now play a more active role in the compliance program and the evolution of the standard, whereas the QSA and the ASVs find it much easier to train their personnel.

Tools

At the time of this writing, PCI Council provides a few useful tools to help track PCI DSS compliance. These are explained in the following:

■ “Prioritized Approach for DSS 1.2” tracking spreadsheet allows for easy compliance program tracking and reporting, whether internal or to the card brands or acquirers. The sheet can be downloaded at www.pcisecuritystandards.org/education/prioritized.shtml.

■ “PCI SSC New SAQ Summary” documents are not just helpful, they are actually mandatory for those validating PCI compliance via an SAQ. The PCI Council provides the fillable documents that can be used for tracking compliance at a small organization. All the SAQs can be obtained for free at www.pcisecuritystandards.org/saq/instructions_dss.shtml

■ “Attestation of Compliance” forms are also provided by the PCI Council. These forms accompany the SAQ during self-assessment. They can be downloaded at www.pcisecuritystandards.org/saq/index.shtml.

To summarize, the most important things to know about PCI Council are as follows:

■ The Council maintains and updates the PCI DSS, and now a PA-DSS and a PED, as well as a set of supporting documents.

■ The Council does not deal with PCI validation process and, specifically, with enforcement via fines or other means. These responsibilities are retained by the card brands.

■ PCI Council also certified security vendors as QSAs and ASVs and maintains current lists of certified vendors, as well as polices the vendors to maintain the integrity of PCI validation. The industry immediately felt the positive impact of PCI Co. The merchants and service providers can now play a more active role in the compliance program and the evolution of the standard, whereas the QSA and the ASVs find it much easier to train their personnel.

Let's look at the QSAs and ASVs in more detail.

QSAs

PCI Council now controls the companies that are allowed to conduct on-site DSS compliance assessments. These companies, known as QSAs, 3 have gone through the application and qualification process, having had to show compliance with tough business, capability, and administrative requirements. QSAs also had to invest in personnel training and certification to build up a team of assessors, also called QSAs.

3In the past, there was a different name for a company (QSAC or Qualified Security Assessor Company) and an individual professional employed by such company (QSA or Qualified Security Assessor).

Note

QSAs are only permitted to conduct on-site DSS assessments. They are not automatically granted the right to perform perimeter vulnerability scans, unless they also certify as an ASV. Many companies today can be found on both lists (QSAs and ASVs) to be able to provide complete PCI validation services to merchants and service providers.

QSAs have to recertify annually and have to retrain their internal personnel. The exact qualification process and the requirements are outlined on PCI Council Web site; however, of particular interest are the insurance requirements. QSAs are required to carry high coverage policies, much higher than typical policies for the professional service firms, which becomes important later. A recent lawsuit (“Merrick Bank v. Savvis,” see more details in [9]) presents an example risk that QSA faces; in this suit, the bank is suing the assessor who validated CardSystems, a target of a massive card data breach, as PCI compliant. Please use Google to find out how the lawsuit progressed and who won; the results will not be known before the book goes to print.

Note

The QSAs are approved to provide services in particular markets: US, Asia Pacific, CEMEA (Central Europe, Middle East, and Africa), Latin America and the Caribbean, and Canada. The qualification to service a particular market depends on QSA's capabilities, geographic footprint, and payment of appropriate fees.

The QSA is a certification established by PCI Co. Individuals desiring this certification must first and foremost work for a QSA or for a company in the process of applying to become a QSA. Then, they must attend official training administered by PCI Council and pass the test. They must also undergo annual requalification training to maintain their status. An individual may not be a QSA, unless he or she is presently employed by a QSA company; however, a QSA can carry the certification between QSA companies when changing jobs.

Tools

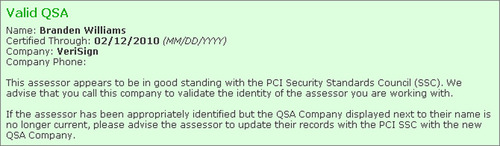

Anybody can look up the individuals with current QSA certification by using QSA Employee Lookup at www.pcisecuritystandards.org/qsa_lookup/index.html.

See Fig. 3.2 for an example.

We cover the tips on working with your QSA in Chapter 11, “Don't Fear the Assessor.” If there is one thing to remember when engaging a QSA, the QSA should be your partner. Treating your QSA like an auditor will only lead to a painful process whereby both parties end up frustrated and disillusioned.

ASVs

As you know, PCI DSS validation also includes network vulnerability scanning by an ASV.

To become an ASV, companies must undergo a process similar to QSA qualification. The difference is that in the case of QSACs, the individual assessors attend classroom training on an annual basis, whereas ASVs submit a scan conducted against a test network perimeter. An organization can choose to become both QSA and ASV, which allows the merchants and service providers to select a single vendor for PCI compliance validation.

It is important to note that ASVs are authorized to perform external vulnerability scans from the Internet, but PCI DSS also mandates internal vulnerability scans (performed from inside the company network), which can be performed by anybody – internal security team or consultant.

We cover all the tips on working with your ASV in Chapter 8, “Vulnerability Management.”

Quick Overview of PCI Requirements

Now it is time to briefly run through all PCI DSS requirements, which we cover in detail in the rest of this book.

PCI DSS version 1.2 is comprised of six control objectives that contain one or more requirements:

■ Build and maintain a secure network

□ Requirement 1: Install and maintain a firewall configuration to protect cardholder data

□ Requirement 2: Do not use vendor-supplied defaults for system passwords and other security parameters

■ Protect cardholder data

□ Requirement 3: Protect stored cardholder data

□ Requirement 4: Encrypt transmission of cardholder data across open, public networks

■ Maintain a vulnerability management program

□ Requirement 5: Use and regularly update antivirus software

□ Requirement 6: Develop and maintain secure systems and applications

■ Implement strong access control measures

□ Requirement 7: Restrict access to cardholder data by business need to know

□ Requirement 8: Assign a unique ID to each person with computer access

□ Requirement 9: Restrict physical access to cardholder data

■ Regularly monitor and test networks

□ Requirement 10: Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data

□ Requirement 11: Regularly test security systems and processes

■ Maintain an information security policy

□ Requirement 12: Maintain a policy that addresses information security

The above-mentioned 12 requirements cover the whole spectrum of information technology (IT) areas as well as venture outside of IT in Requirement 12. Some requirements are very technical in nature (e.g., Requirement 1 calls for specific settings on the firewalls), and some are process and policy-oriented (e.g., Requirement 12) and even go into contract law (some of the subrequirement in Requirement 12 cover the interactions with MSPs.

The detailed coverage of controls makes things easier for both the companies that have to comply with the standards, the auditors (in case of Sarbanes–Oxley [SOX] or other laws and standards), or the assessors (in case of PCI DSS). For example, when compared to the SOX Act 2002, companies do not have to invent or pay for somebody to invent the controls for them; they are already provided.

What is interesting is that almost every time there is a discussion about PCI DSS, someone would claim that PCI is too prescriptive. In reality, PCI being prescriptive is the best thing since antivirus solutions invented automated updates (hopefully, you can detect humor here). PCI DSS prescriptive nature simply means that there is some specific guidance for people to follow and be more secure as a result (if they follow the spirit and not only the letter of PCI standards)! Sadly, in many cases, the merchants who have to comply with PCI DSS and who still think it is “too fuzzy” and “not specific enough” are the ones basically asking for a compliance and security to do list or a task list; and no external document that guarantees that your organization will be secure can ever be created.

In particular, when people say “PCI is too prescriptive,” they actually mean that it engenders “checklist mentality” and leads to following the letter of the mandate blindly, without thinking about why it was put in place – to protect cardholder data, to reduce, or to share risk/responsibility. For example, it says “use a firewall,” so they deploy a shiny firewall with a simple “ALLOW ALL<->ALL” rule – an obvious exaggeration that clarifies the message here. Or, they have a firewall with a default password unchanged. In addition, the proponents of “PCI is too prescriptive” tend to think that fuzzier guidance (and, especially, prescribing the desired end state and not the tools to be installed) will lead to people actually think about the best way to do it.

So, the choices to write security-motivated regulatory guidance are as follows:

1. Mandate the tools (e.g., “must use a firewall”) and risk “checklist mentality,” resulting in both insecurity and “false sense” of security.

2. Mandate the results (e.g., “must be secure”) and risk people saying “yes, but I don't know how” and then not acting at all, again leading to insecurity.

The author team is of the opinion that in today's reality #1 works better than over pill #2 (and that is why I like PCI more), but with some pause to think, for sure. Although the organizations with less mature security programs will benefit at least a bit from #1, organizations with more mature programs might be able to operate better under #2. However, data security today has to cover the less-enlightened organizations, which makes #1 choices – embodies by PCI DSS – the preferred one.

As a far as scope of PCI DSS within the organization is concerned, PCI compliance validation may affect more than what you consider the “cardholder environment.” According to PCI DSS 1.2, the scope can include the cardholder data environment only if adequate network segmentation is in place. In most cases, this implies the use of dedicated firewalls and nonroutable virtual local area networks (VLANs). If you do not have such controls in place, the scope of PCI compliance validation will cover your entire network. Think about it: if you cannot ensure that your cardholder data is confined to a particular area, then you cannot focus on this area alone, and you have to look everywhere.

Note

Just because a POS system is on the list of compliant payment applications (PA-DSS), it does not mean that your particular implementation is compliant. Also, it definitely does not mean that your entire organization is PCI compliant. You should work with the application vendor and with your QSA to verify this.

In order for the device to be added to the PA-DSS list, the payment application, online shopping cart, or POS vendor has to show and document the secure method for their application deployment. However, it is ultimately the merchant responsibility to follow the secure and compliant deployment guidance.

For the benefit of consumers who may be more familiar with a brand name rather than a parent company, PCI compliance is validated for every brand name. Thus, if a company has several divisions or “doing business as” (DBA) names, each entity has to be validated separately. For reporting simplicity, the ROCs or SAQs may note that they include validation of multiple brand names.

You may discover that sometimes you are unable to comply with the letter of PCI DSS while still striving for its spirit. For example, you may need to temporarily store cardholder data unencrypted for troubleshooting purposes or to use a password of less than mandate minimum length on a legacy system. As long as you follow reasonable precautions, card brands understand this need. Another example may include recording certain call-center conversations for customer service purposes. Again, card brands understand that these recordings may contain cardholder data, so accommodations are made accordingly.

In many cases, compensating controls have to be used to achieve compliance when your company cannot exactly meet a given requirement. The important thing to remember about compensating controls is that they have to go beyond the requirements of PCI to provide the same or higher assurance of cardholder data protection. When compensating controls are claimed, additional documentation must be completed. Please see Chapter 12, “The Art of Compensating Control” for detailed coverage of compensating controls.

Changes to PCI DSS

One of the key challenges for any security standard is to change fast enough to follow the threat changes (and those change literally every day since criminal computer underground has to evolve to stay in business) and to change slow enough to still be considered a technical standard (and not simply advise to “do the right thing”). For prescriptive technical standards that directly call out security controls, such as firewalls, network intrusion prevention, and vulnerability scanning, the challenge is even more extreme.

In fact, today PCI DSS is sometimes criticized for being “constantly in flux” and for “not moving fast enough” at the same time, but by different people.

The changes are that the PCI standards are guided by the PCI Council document called “Lifecycle Process for Changes to PCI DSS”[10]. The document describes the following stages for each standard revision:

1. Market Implementation (9 months)

2. Feedback Begins (3 months)

3. Feedback Review and Decision (8 months)

4. New Version/Revision and Final Review (3 months)

5. Discuss New Version/Revision (1 month)

The overall process takes 24 months for each DSS revision (whether major from 1 to 2, which has not happened yet, or minor such as from 1.0 to 1.1) and always includes extensive public commenting and review periods to incorporate the input from all stakeholders.

PCI DSS and Risk

The relationship between PCI DSS and risk management has been an unstable one. It was mentioned previously in the context of PCI's goal for reducing the risk of card transaction and for preventing the merchants from accepting the risk of someone's loss. On the other hand, many people point out that PCI DSS presents a list of control with no regard to organization's own risk assessment. Let's explore the relationship of PCI and risk a bit further.

First, a common question: can one claim that PCI increases the merchant's overall risk? When people ask that question they usually imply that PCI added the risk of loss via noncompliance fines and raised fees to the risk of direct losses due to card theft from a merchant's environment (such as reputation damage, cost of new security measures, and monitoring)? The answer is clearly a “no,” since before PCI, most of the negative consequences of a card theft, even a massive one, were not falling upon the merchant shoulders but on others such as card-issuing banks. PCI, on the other hand, creates a powerful motivation for protecting the data on the merchant side.

Still, despite that reality about PCI, many CEOs or CFOs are asking the question, “Why would I need to spend the money on PCI?” And, no, the answer is not “Because there are fines” (even though there are fines indeed). The answer is that the list of negative consequences due to neglecting data security and PCI DSS is much longer than fines.

Your company's contract with the acquiring bank probably has a clause in it that any fines from the card brand will be “passed through” to you. With all compliance deadlines passed, the fines could start tomorrow. Visa USA has announced that it will start fining acquirers (which will pass on the costs to the merchant) between $5000 and $25,000 per month if their Level 1 merchants have not shown compliance. In addition, the fines $10,000 per month may already be imposed today for prohibited data storage by a Level 1 or Level 2 merchant.

On top of that, if both noncompliant and compromised, higher fines are imposed as well. However, believe it or not, if compromised, this will be the least of your concerns. Possible civil liabilities will dwarf the fines from the card brands. Some estimates place the cost of compromise at $50 to $250 per stolen account (per stolen, and not per one used for fraud, which will likely be a subset of the whole stolen card pool). It is known that some companies that have been compromised have been forced to close their doors or sold to competition for nominal amount. According to PCI Council study, the per capita cost of a data breach has gone up more than 30 percent in the past year.

Let's use The TJX Companies, which operates stores like TJ Maxx, Marshalls, and so on, as a case study. On January 17, 2007, TJX announced that they were compromised. Because they did not have robust monitoring capabilities such as those mandated by PCI, it took them a very long time to discover the compromise. The first breach actually occurred in July 2005. TJX also announced that more than 90 million credit-card numbers were compromised. In addition to the fines, lost stock price, and direct costs of dealing with the compromise, over 20 separate law suits have already been filed against TJX; some have been converted to class-action status.

Whether you believe your company to be the target or not, the fact is that if you have cardholder data, you are a target because you are someone's “ticket to a better life” via criminal business. You and your organization are simply someone's sheep to be fleeced, and your losses are their gains. Cardholder data is a valuable commodity that is traded and sold illegally worldwide. Organized crime units profit greatly from credit-card fraud, so your company is definitely on their list if you deal with card data. International, federal, and state law enforcement agencies are working hard to bring perpetrators to justice and shut down the infrastructure used to aid in credit-card-related crimes; however, thousands of forum sites, Internet chat channels, and news groups still exist, where the buyers can meet the sellers. Data breaches like the one at TJX are not the work of simple hackers looking for glory; well-run organizations from the Eastern European block [11] and selected Asian countries [12] sponsor such activity and earn a great living from various illegal hacking activities.

The Web site http://datalossdb.org maintains the history of the compromises and impacts in terms of lost card numbers and other records. Since 2005, over 1 billion personal records (a mix of cards, identities, etc.) have been compromised. This includes companies of all sizes and lines of business. If the industry does not get this trend under control, the US Congress will give it a try.

Finally, and few people actually know it, but PCI DSS does mandate a formal risk assessment, not just a list of controls to implement! The Requirement 12.1.2 states that the information security policy must “include an annual process that identifies threats, and vulnerabilities, and results in a formal risk assessment.”

Benefits of Compliance

While the inclusion of benefits is redundant – after all PCI DSS compliance is mandatory for the organizations that deal with payment cards! – it is worthwhile to highlight the fact that PCI DSS has important benefits for the merchants, acquiring banks, issuing banks, as well as for the public at large.

If we are to mention one benefit, PCI DSS has motivated the security improvements like nothing else before it. Many organizations lived through the virus-infested 1980s, then worm-infested and spammy 1990s, and then through heavy data loss early 2000s without doing anything on security. PCI DSS had a huge impact on the laggards to get better.

Case Study

Much of this book focuses on case studies where a company makes a mistake, or fails to do something that result in a breach. This case study is a nice change of pace where we examine someone doing something right!

The Case of the Developing Security Program

Yvette's Evangelical Emporium is a small chain of 50 stores supplying religious supplies to local churches and individuals. Yvette started her business in 1990 with a single store. Throughout the 1990s, she was able to open several new stores in neighboring counties and states, eventually building a 10 retail location business by 2000. In 2002, she took advantage of a depressed economy, and using some capital from investors and a significant trust that matured, she expanded her operation to 25 stores in 3 years and continued to expand over the next 4 years to double her size.

In 2005, Yvette realized that she needed to formalize her IT division and hired Erin, a progressive and security-minded IT executive, as her chief information officer. Erin presented a plan to standardize and build out her infrastructure so that future growth could be done in a cookie-cutter fashion; thus, saving millions in deployment and maintenance costs.

By 2006, they crossed the threshold from a Level 2 Visa merchant to a Level 1 Visa merchant and knew they would quickly need to put a solid PCI compliance program in place. Erin knew from her previous experience that small companies struggled with information security and made it a point to build in basic information security fundamentals into her IT operations, but they did not meet the baseline PCI DSS requirements and needed to be reworked.

Because of her new reporting levels for PCI, Yvette hired Steve to serve as the chief information security officer, reporting directly to her. Steve's task was to build an information security program that addressed PCI immediately, but would expand to be more applicable to information security such that future regulation would only require minor tweaks to the program.

Steve and Erin worked closely together to build a common set of controls to be rolled out to the entire company. Steve knew that PCI was a priority but considered everything he did in light of the ISO security framework (ISO17799 at the time). In some cases, he found that ISO far exceeded specific PCI requirements like in Business Continuity and Risk Assessments, and he found unique parts of PCI that were much more granular than ISO, like the treatment of sensitive authentication data (PCI Requirement 3.2). Steve's efforts ultimately paid off in spades as his information security program matured. Recent changes and additions to restrictions on healthcare data (which Yvette housed as part of an employee self-insurance program) and state data breach notification laws were already addressed by the program as it matured, and Yvette's cost associated with protecting data was much less than her competitors who only chased standards with immediate noncompliance repercussions.

Note

It is well-known that initial PCI DSS creators were well aware of ISO 17799 and other security standards. This awareness leads to the fact that if your organization has a solid security management program based on ISO/IEC 27002 (a modern descendant of ISO/IEC 17799 and BS7799), your PCI effort will be relatively easy and you will gain both solid security and compliance as a result. It is also likely that compliance with other regulations will not be overly onerous. PCI is more granular, whereas ISO is more broad, but they are largely in sync!

The Case of the Confusing Validation Requirements

Garrett's Gas Guzzling Garage operates 800 car repair locations across the United States. Garrett's recently opened 20 locations in Mexico City to help maintain and upgrade the fuel efficiency of old cars. Garrett is considered a Level 1 merchant in the United States but set up a different entity in Mexico City, and processes and settles locally with Bancomer. Although Garrett authorizes and settles locally in Mexico City at his small regional headquarters, he shares the data with the US-based parent for backup and analysis purposes.

His business is booming in Mexico City, and that business quickly became a Level 2 merchant. According to MasterCard's new validation requirements, this would mean that Garrett must have a QSA perform an on-site assessment of compliance for both locations. He was already doing this in the United States based on his Level 1 status, but now faces additional costs for doing this locally in Mexico City.

“But wait,” some of you are saying, “What about Visa's rules?” Certainly glad you asked that! According to Visa, if a smaller, wholly owned subsidiary shares infrastructure and data with a parent company considered a Level 1, then that smaller subsidiary should also be viewed as a Level 1 and perform the same level of validation.

Back to Garrett, even though the 20 Mexico locations process through Bancomer, the data is shared with the US headquarters for backup and analysis. According to Visa's rules, the Mexican entity is considered Level 1 based on its relationship with the parent, and a Level 1 assessment must be performed.

As always, when in doubt, ask your acquirer what is expected of you. Your mileage may vary when it comes to some of these intricate rules. Some acquiring institutions may still treat certain subsidiaries as lower levels depending on the circumstances.

Summary

PCI refers to the PCI DSS established by the credit-card brands. Any company that stores, processes, or transmits cardholder data has to comply with this data-protection standard. Effectively, all the target compliance dates have already passed, so if your company has not validated compliance, you are at risk of fines and other negative consequences of insecurity and noncompliance. The PCI is composed of 12 requirements that cover a wide array of business areas. All companies, regardless of their respective level, have to comply with the entire standard as it is written. The actual mechanism for compliance validation varies based on the company classification, driven by the individual card brand, transaction volume, exact method of accepting cards, etc. The cost of dealing with data breaches keeps rising, as does their number; noncompliance exacerbates the loss in case of a breach. Companies that do not take data security and compliance efforts seriously may soon find themselves out of business.

Now is the time to start the journey toward data security and compliance: get an endorsement from the company's senior management and business stakeholders, and start fulfilling your obligations and protecting the data.

References

[1] Sinclair Jr, UB., I, Candidate for governor: and how i got licked (1935). (1994) University of California Press 0-520-08198-6; repr. P. 109.

[2] PCI Council Website, Article # 5410, http://selfservice.talisma.com/article.aspx?article=5410&p=81; [accessed 31.08.2009]..

[3] PCI Council Glossary, Entry Service Provider, http://selfservice.talisma.com/display/2n/index.aspx?c=58&cpc=MSdA03B2IfY15uvLEKtr40R5a5pV2lnCUb4i1Qj2q2g&cid=81&cat=&catURL=&r=0.73831444978714; [accessed 17.07.2009]..

[4]

[5] Ten Common Myths of PCI DSS, www.pcisecuritystandards.org/pdfs/pciscc_ten_common_myths.pdf; [accessed 17.07.2009]..

[6] Visa Cardholder Information Security Program for Service Providers web page, http://usa.visa.com/merchants/risk_management/cisp_service_providers.html; [accessed 02.08.2009]..

[7] PCI and Your Third-Party Service Providers – First, the Bad News, http://treasuryinstitutepcidss.blogspot.com/2009/07/pci-and-your-third-party-service.html; [accessed 10.08.2009]..

[8] PCI Security Standards Council website, www.pcisecuritystandards.org/; [accessed 17.07.2009]..

[9] Merrick Bank v. Savvis Update: Savvis Files Motion to Dismiss., http://infoseccompliance.com/2009/06/23/merrick-bank-v-savvis-update-savvis-files-motion-to-dismiss; [accessed 17.07.2009]..

[10] Lifecycle Process for Changes to PCI DSS, www.pcisecuritystandards.org/pdfs/OS_PCI_Lifecycle.pdf; [accessed 17.07.2009]..

[11] Black Hat: Fighting Russian Cybercrime Mobsters., www.informationweek.com/blog/main/archives/2009/07/black_hat_fight.html; [accessed 11.08.2009]..

[12] Chinese Hackers Attack Web Site Over Uighur Film., www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601081; [accessed 11.08.2009]..

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.