Adaptation

Adjusting to Differences

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

—attributed to Albert Einstein

PART 1 OF THIS BOOK established the context of semiglobalization and developed a framework for thinking about the differences across countries and a template for evaluating cross-border strategic options in light of such differences. Now we turn to what to do about differences, starting with the strategy of adaptation, or adjusting to differences.

Some degree of adaptation is essential for virtually all border-crossing enterprises. Consider just two of the examples discussed in part 1:

• Cement is close to a pure commodity produced with a mature technology, but Cemex must still adjust to international differences in energy prices, the mix of demand between bagged and bulk cement, etc.

• Wal-Mart has historically performed more poorly the farther it gets from Bentonville, Arkansas. Inflexibility and under-adaptation seem to be the most obvious reasons. Visible manifestations include such merchandising missteps as stocking U.S.-style footballs in soccer-mad Brazil. But the problems run much deeper: I estimate that of fifty policies and practices that distinguish the company domestically, thirty-five were historically carried over more or less completely, and twelve at least partially, to its international operations—an amazing degree of consistency in an industry subject to large cross-border differences.

The example of Wal-Mart, in particular, illustrates what seems to be a common bias toward under-adaptation in cross-border strategies.1 Part of the solution, as suggested earlier, is to analyze the differences that still divide countries instead of ignoring them because of a belief that they are or will become insignificant. But it is also important for companies to think through the full array of levers available to adapt to those differences—tools that improve the terms on which they can actually achieve adaptation. To dig deeper into the challenge of adaptation and the variety of possible responses to it, this chapter will explore in some detail an industry that demands great variety—major home appliances—with a particular focus on the strategies of the ten largest competitors worldwide.2 Then, using many additional examples, it will discuss levers for adaptation more broadly before turning to some of the organizational issues that arise around managing adaptation.

The Major Home Appliance Industry

Although the major home appliance industry has been consolidating within the United States and Western Europe since the 1960s, globalization across regions began in earnest in the mid-1980s, with a round of big acquisitions. In 1986, Electrolux, the leader in Europe, acquired White Consolidated, the third-largest U.S. producer. The major U.S. competitors responded over 1989–1990: Whirlpool, the largest, acquired Philips’s major home appliance business, which was the second-largest in Europe but struggling; General Electric, the second-largest U.S. producer, bought a stake in the home appliance business of the United Kingdom’s GEC; and Maytag, the fourth-largest, acquired Hoover, expanding its footprint to the United Kingdom and Australia. The 1990s saw international expansion by other competitors from Europe, particularly Bosch-Siemens of Germany, as well as from Asia: Japanese companies such as Matsushita were joined on the world stage by, among others, Korean companies LG and Samsung and China’s Haier.

The case for global expansion was made most forcefully in a 1994 interview by David Whitwam, the CEO under whom Whirlpool acquired Philips’s business: “Over time, our industry would become global, whether we chose to become global or not. With that said, we had three choices. We could ignore the inevitable—a decision that would have condemned Whirlpool to a slow death. We could wait for globalization to begin and then try to react. Or we could control our own destiny and try to shape the very nature of globalization in our industry.”3

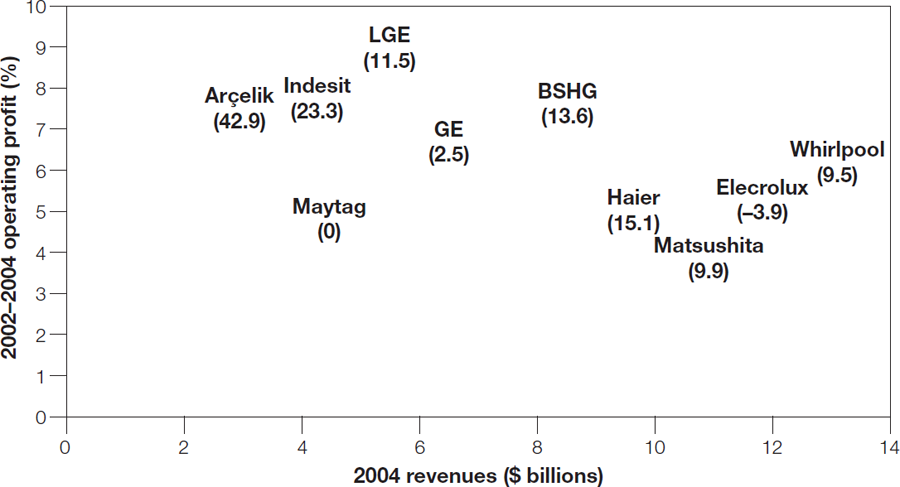

But international expansion has failed to bolster performance. Figure 4-1 shows the recent profitability of the ten largest competitors worldwide.4 In light of the profitability data, the firms that moved early to expand across regions—Electrolux and the four U.S. majors—do not seem to have tapped into early-mover advantages. Nor have they managed to grow their home appliance businesses particularly rapidly: the early globalizers also fall into the bottom half of the top ten in terms of revenue growth rates between 2002 and 2004 (the numbers in parentheses in the figure). In the same vein, the biggest of the top ten—the firms that generally have broader geographic footprints—have not been the most profitable. So, while consolidation has taken place in this industry, it has generally dragged down the performance of the consolidators. Why haven’t things played out the way they were supposed to?

Profitability versus size (and growth rates) for the top ten competitors in major home appliances

Sources: Annual reports of companies shown on chart; Freedonia Group, “World Major Household Appliances: World Industry Study with Forecasts to 2009 and 2014,” Study 2015 (Cleveland: Freedonia Group, January 2006); Pankaj Ghemawat and Catherine Thomas, “Arçelik Home Appliances: International Expansion Strategy,” Case 705-477 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2005); Pankaj Ghemawat and Thomas M. Hout, “Haier’s U.S. Refrigerator Strategy 2005,” Case 705-475 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2005); and Global Market Information Database. Matsushita profit margins are for 2002–2003; GE and Haier numbers are estimates.

Whirlpool made the most explicit case for adding value by expanding globally with a Ted Levitt–like faith in consumers’ desire for the same products everywhere. As the company’s annual report for 1987 stated, “Consumers in major industrialized countries are living increasingly similar lifestyles and have increasingly similar expectations of what consumer products must do for them.”

The trouble with such reasoning, in major home appliances as in many other industries, is, as Charles Darwin once put it, that it seems to have been based on inner consciousness rather than observation. As of the early 2000s, the leading manufacturers of major home appliances still offered thousands of varieties—as many as fifteen thousand in the case of Electrolux. The CAGE framework from chapter 2 helps flush out the full range of cross-border differences that have prevented preference convergence, and the diagnostic tools from chapter 3 shed light on the extent to which these differences dilute (already weak) incentives for cross-border expansion (table 4-1).

Working through table 4-1 from left to right, the number of varieties required to compete effectively across multiple markets is swelled, first of all, by a range of cultural differences—some idiosyncratic, others derived from other, more fundamental differences. An example in the former category was provided by clothes washers, a category in which such diversity is often supposed to be relatively limited—but really isn’t:

In France, top-loading machines accounted for about 70 percent of the market: front-loading machines typically sold at a small discount to top-loaders, despite the fact that the production costs were comparable. West German consumers preferred front-loaders with high spin-speeds of 800 rpm or more. Italian consumers preferred 600–800 rpm, front-loading machines. The British prefer 800 rpm front-loaders, but with a hot and cold water fill rather than cold-water-only supply.5

An even larger part of preference diversity seems to derive from other, more fundamental differences across countries. Thus, from a cultural standpoint, national cuisines have a significant impact on demand in a number of appliance categories. For example, compared with U.S. refrigerator buyers, Germans want more space for meat; Italians prefer special compartments for vegetables; and Indian families, with a mix of vegetarians and nonvegetarians, require internal seals to stop food smells from mingling. To hold Christmas turkeys, ovens are larger in England than in Germany, where geese are cooked. Germans also don’t need self-cleaning ovens, since they bake at lower temperatures than the French do. And Indian households generally don’t need ovens at all.

Furthermore, preferences concerning older categories of home appliances are relatively well formed. As one marketing expert explained, “The home is the most culture-bound part of one’s life. Consumers in Paris don’t care what kind of refrigerator they are using in New York.”6

Administratively, requisite variety in home appliances is increased by variation in electric standards, with thirteen major types of plugs and wall outlets, as well as different voltages and frequencies, in use around the world.7 Other kinds of regulations, particularly environmental ones, also vary significantly by country. And protectionism combines with high transport costs to make otherwise identical varieties produced in different locations imperfect substitutes for each other—in other words, these factors constrain intra-industry trade (one way of increasing the varieties on offer without necessarily increasing the number produced per location). Trade historically took place mostly within regions and has become even more regionalized in recent decades.8

Other relevant geographic factors include the climate. Thus, air conditioners aren’t needed where (or when) it isn’t hot, and clothes dryers have proven less successful in the Mediterranean sun.

In terms of strictly economic differences, probably the single most important driver of cross-country variation is the local income level. A refrigerator can account for the bulk of annual per-capita income in India, compared with a few percentage points in the United States. As a result, refrigerator penetration is still very limited in India, despite the heat, and the varieties sold there are much smaller, simpler, and cheaper than those in the United States. Other economic factors that matter greatly are variations in the availability and prices of substitutes or complements such as space and electricity. U.S. buyers generally have the most living space and, therefore, tend to buy larger varieties and tolerate higher noise levels. Electricity costs are often higher outside the United States, focusing more attention on energy efficiency. Unreliable electricity supply also creates niches, such as the Chinese interest in electronic controls that reset automatically after power failures.

All this cross-border variation is superimposed on significant domestic differences in preferences about characteristics such as color, material, size, energy efficiency, noisiness, other aspects of environmental friendliness, basic layout, the design of the door, the configuration of shelves, the position of the freezer, inclusion of a defroster, and controls. This compounds the challenges of dealing with variety and complexity. In addition, the discussion above focused on the cross-border differences that drive preference diversity rather than on all the differences that matter. Many of the additional differences discussed in chapter 2 continue to apply in this industry and make it even more difficult to manage across borders. Thus, linguistic limitations would seem to undercut Electrolux’s infamous “Nothing sucks like an Electrolux” advertising campaign in the United States.

The one kind of cross-country difference that does have a significant effect in the opposite direction—that is, it encourages cross-border expansion—is the difference in labor costs, which can account for 20 to 30 percent of sales revenue for domestic production in high-cost countries. But, again, given relatively high transport costs, the product subcategories that this opens up to cross-border, particularly interregional, competition are limited. Thus, although Haier ships many under-the-counter refrigerators from China, the world’s lowest-cost production platform, to the United States, transport costs preclude the profitable export of large refrigerators—even before U.S. tariffs are taken into account.

To look more systematically at industry economics, consider different categories of expenditures as a percentage of revenues. In terms of the intensity of advertising, R&D, and labor, the major home appliance industry ranks higher than the median manufacturing industry, but falls far short of the ninetieth percentile. It also lags the auto industry in terms of advertising intensity and, particularly, R&D intensity, suggesting weaker incentives for cross-border expansion—even though many managers in home appliances regard autos as a big cousin and bellwether. So, there is limited impetus to override the variety and complexity required to compete across borders.

From our perspective, unlike that of would-be consolidators, this is a help rather than a hindrance. Not only does the major home appliance industry pose an extreme adaptation challenge, but—since it lacks a dominant driver of value creation through global expansion—it has also afforded different competitors room to try out very different ways of responding to that challenge. In particular, the competitive strategies followed by the ten largest competitors, which I will outline next, span most of the levers for responding to adaptation challenges.

Competitive Strategies

Some of the top ten competitors in major home appliances follow the basic competitive strategies stressed in single-country strategy, low cost (e.g., Matsushita and Haier) or differentiation (e.g., Bosch-Siemens and LG). Obviously, a deep enough competitive advantage in terms of cost or differentiation can offset at least some of the pressures to adapt to different markets. But differences across countries have mandated significant modifications to such basic strategies. In response to pressures from competitors in other countries, Matsushita has had to retool its scale-based cost-leadership strategy of producing relatively standardized products in a few plants in Japan. Haier’s exports to the United States under its “difficult first, easy second” approach have led not only to a focus on compact refrigerators and other easy-to-transport products, but also to an unusual partnership with an entrepreneur, Michael Jemal, president of Haier America. And Bosch-Siemens’s and LG’s product offerings vary substantially across emerging and developed markets. Understanding these and other responses to differences, and thereby maximizing the degrees of strategic freedom, requires going beyond characterizations in terms of low costs versus differentiation—or other components of the ADDING Value scorecard. Keeping score is not a substitute for thinking about strategy content.

Adopting this perspective, the strategies followed by the largest home appliance competitors span all of the main levers for responding to adaptation challenges that are illustrated in the shaded ovals in figure 4-2.

The first, most obvious approach to adapting to differences across countries is variation. Electrolux of Sweden—which represented the cumulation of the mergers of more than five hundred companies and which offered fifteen thousand varieties by the late 1990s—exemplified this approach to an extreme. In fact, at one point, Electrolux even experimented with individualization—allowing customers to mix and match using more than ten thousand combinations of colors and materials in refrigerators alone!9 But simple variation proved insufficient to cater to all the different requirements implied by the industry’s broadest geographic presence and, given poor performance, Electrolux has recently attempted some consolidation.

A second lever for dealing with adaptation challenges involves focus on particular geographies, products, vertical stages, and so forth as a way of reducing heterogeneity. Thus, smaller players in the top ten—companies such as Indesit of Italy, Arçelik of Turkey, and Maytag (prior to its acquisition by Whirlpool in 2005)—focus on particular regions instead of operating globally. Haier’s focus on compact products has already been mentioned. And an example of focus on a vertical stage is provided by Brazilian compressor manufacturer Embraco, which holds nearly a quarter of the global market—nearly twice the market-leading share of Whirlpool in home appliances. Since Whirlpool also owns a major interest in Embraco, it seems that the difference between the extent of their global consolidation reflects product characteristics—for compressors, high R&D intensity, and particularly high value-to-weight ratios—rather than management approaches.

A third lever for adaptation involves externalization—through joint ventures, partnerships, and so forth—as a way of reducing its internal burden. An example is Haier’s partnership with Michael Jemal as a way of adapting to the unfamiliar requirements of the U.S. market. A number of other top ten competitors also emphasized externalization. In particular, GE Appliances acquired a 50 percent stake in a large joint venture in the United Kingdom, GDA, tied up with a major retailer in Japan to access distribution and limited its investment in China by branding products from local manufacturers. (However, GE sold off its 50 percent stake in GDA to Indesit in 2002, reinforcing its regional focus on North America.)

A fourth lever for adaptation is design to reduce the cost of, rather than the need for, variation. Probably the clearest example of this lever in major home appliances is provided by Indesit, which has been quite successful with a strategy in which each plant produces one category of home appliance products using one basic product platform.

A final lever for adaptation is innovation, which, given its cross-cutting effects, can be characterized as improving the effectiveness of adaptation efforts. Market leader Whirlpool provides one of the best examples of this approach among the home appliance majors. After a relatively halfhearted attempt at platforming, Whirlpool has, since 2000, shifted its strategic emphasis to “brand focused value creation” involving “innovation from everyone and everywhere.” The company has benefited from introducing the Duet front-loading washer, designed by its European arm, into the U.S. market, which had long favored top-loaders. But it has had less success with its more ambitious attempt to develop a “world washer.”

This discussion of the top ten producers’ competitive strategies has focused on adaptation as a response to the differences across countries. In addition, virtually all the competitors profiled paid some attention to two other strategies: aggregation at the regional level—either by focusing on a particular region or in terms of how they were organized across regions—and arbitrage, as a way of reducing costs in the face of continuing pressures on prices and margins. Strategies of aggregation and arbitrage are the focus of chapters 5 and 6, respectively.

Levers and Sublevers for Adaptation

The need to eschew the extremes of total localization and standardization in deciding how to adapt is not new. What is new is the assemblage of multiple levers for adaptation shown in figure 4-2: it provides a menu of possibilities that goes beyond vague injunctions to “get the balance right” or “glocalize.” And since variety is the essence of adaptation, each of these levers can and will be articulated further, into an array of sublevers (table 4-2).

Note that this is not an exhaustive list of sublevers. It is easy to think of other sublevers that might serve as bases of adaptation, at least in specific industry or company contexts. For example, under externalization, one might add licensing and other forms of interfirm contracting.10 But the twenty sublevers listed in table 4-2 constitute a large enough set to make the basic point that there are many ways to adapt.

Nor are the sublevers, and even the levers, mutually exclusive. That said, given their distinct requirements and ramifications, trying to achieve superior leverage along all the different levers or sublevers is probably a foolish pursuit. For one thing, excellence at any form of adaptation typically requires an aligned organization. A second reason that strategy requires choices to be made has to do with complexity, the bane of the competitors in the major home appliance industry. Note that complexity can be killer in terms of most of the value components identified in the ADDING Value scorecard: it can undercut scale economies; elevate costs; reduce differentiation or the ability to serve customers by blurring image or creating real conflicts—with channels, for example; exacerbate risk and inflexibility; and use up rather than augment (other) resources, particularly managerial bandwidth. And finally, the need to pick and choose is also related to the requirements for aggregation and arbitrage as well as for adaptation—requirements that we will take up in the following chapters.

In other words, the list of levers and sublevers in table 4-2 provides a menu from which to select items rather than a checklist of items to be ticked off: attempting the latter would typically lead to the corporate equivalent of indigestion. And while such a menu does not, in and of itself, solve the problem of strategic choice, it should, by expanding the set of possibilities, permit companies to improve the terms on which they achieve adaptation. For example, as discussed earlier, Douglas Daft had limited success trying to make Coke more adaptive by reconsidering which policies would be allowed to vary by country as opposed to being set at headquarters in Atlanta. Explicit attention to a broader array of levers and sublevers might have helped. So consider them in a bit more detail, illustrated with a range of examples.

Variation is the most obvious way of adapting to differences across countries. It is also ubiquitous. Variation encompasses changes in products but also in policies, business positioning, and even metrics (e.g., target rates of return). Social scientists, emulating biologists, have long stressed the critical role of variation in evolutionary improvements through the cycle of variation, selection, and retention or amplification. Seen from a distinctively strategic perspective, the variation should not be blind: rather, it needs to be guided, and strategy supplies that guidance while leaving room for incremental refinements.

Products

Even products that are supposedly standardized have to be varied a great deal. In adapting Windows and, more recently, Vista, Microsoft contended with languages such as Hebrew that flow from right to left and German, with words about 30 percent longer than English words (requiring changes in the user interface); icons and bitmaps that weren’t universally acceptable; and disagreements about boundaries embedded in maps—not to mention variations in piracy rates and per-capita income levels. Unilever offers more than 100 variants of its global Lux brand of soaps around the world. And even Coke Classic varies in sweetness and other taste dimensions around the world. In fact, branding guru Martin Lindstrom reckons that Pringles potato chips is the only major consumer product that is widely available and totally standardized—and that Procter & Gamble (P&G) imposes significant penalties on itself by insisting on that much uniformity.11

The variations described above are relatively minor modifications to what might otherwise be described as global products. Other products—even at Coca-Cola, considered one of the world’s most globally standardized companies—are often much more idiosyncratic to particular countries. Think of Coke’s two-hundred-plus products in Japan, as described in the box “Coke in Japan” in chapter 1. Visitors (mainly American) to Coke’s Tastes of the World exhibit in Atlanta are reported to often spit out many of the featured products from Japan and elsewhere, since the tastes are jarringly alien.12

Policies

The need to vary policies across countries can be somewhat less obvious than the need to vary products. Consider the case of Cleveland-based Lincoln Electric, which produces both welding machines and consumable products for those machines.13 Lincoln Electric has been one of the most frequently taught Harvard cases of all time because it outperformed its competitors—including much larger firms such as General Electric and Westinghouse—in its home market through industry-leading productivity levels. These, in turn, were achieved through the use of piecework and supporting human resource policies.

As Lincoln Electric has expanded abroad, it has focused on establishing a presence in the largest markets around the world. It might have done better to use the CAGE framework to select markets: it has done much better in countries that resemble the United States in allowing unrestricted use of piecework. In addition, the company is apparently starting to do better in other environments as well, where piecework isn’t allowed. It manages this by thinking hard about mixing and matching policies in a way that strikes the best balance possible between internal consistency and fit with the external environment—rather than naively emphasizing one or the other.14

Repositioning

Changing the overall positioning of a business is somewhat distinct from, and broader than, changing products or even policies. As outlined in chapter 1, after Coke got serious about doing more than simply skimming the cream off big emerging markets such as India and China, it repositioned itself to a strategy of much lower margins and higher volumes, a strategy that involved lowering price points, reducing costs, and expanding availability.

Another, even more dramatic example of repositioning from the same broad category of beverages is provided by Jinro, which may be less familiar than Coke to most readers, but is the world’s top-selling brand of spirits by volume. The bulk of its sales are accounted for by its domestic market in Korea, but Jinro has—despite a taste compared (by Westerners) to embalming fluid—expanded into several dozen countries, with a major focus on Japan, where it is the market leader.15 In addition to taking more than two decades, the achievement of market leadership in Japan has required a reduction in sugar content to one-tenth the original level; a reformulation to allow the product to be drunk diluted with hot or cold water (instead of straight, as in Korea); very different packaging aimed, in part, at achieving more of a resemblance to whiskey; the adoption of a premium pricing position (unlike the one targeted in many of Jinro’s other export markets); and the use of Caucasian models in its TV commercials, to the point that a majority of Japanese customers do not know that Jinro is from Korea.16

A final sublever here concerns the adjustment of metrics and targets across countries. As described in chapter 3, average profitability varies greatly across the same industry in different countries, suggesting that profitability targets may have to be set at different levels for different countries if a company is serious about penetrating all of them. Thus, Arçelik accounts for more than 50 percent of the Turkish market for home appliances because of more than twenty-five hundred exclusive retail outlets—and earns double-digit margins there. It probably wouldn’t expand overseas at all if it insisted on earning comparable margins, even though some such expansion probably does make sense for reasons including risk reduction: thus, an economic crisis that caused Turkish demand to decline by one-third in 2001 was the spur for its current internationalization drive.

Of course, having made this point, I should add that this logic should not be pursued to the point at which it leads to value destruction rather than value addition. Thus, Whirlpool has maintained a large European presence despite being much less profitable there than at home, partly as a way of increasing leverage vis-à-vis Electrolux by denying its competitor a “home sanctuary.” But given the arithmetic of the situation—the $1 billion paid for Philips’s European business, the estimates of subsequent losses there, and the time value of money combine to imply a net present cost more than one-half of Whirlpool’s current market value—the company should probably have found a different, less costly mode of participating in the European market.

Focus to Reduce the Need for Variation

The trouble with relying exclusively on variation as a lever for adaptation is that it increases complexity. One, often complementary, lever for keeping complexity under control is to focus or purposefully narrow scope so as to bite off a manageable mouthful and thereby reduce the amount of adaptation required. I will elaborate on four specific sublevers: product focus, geographic focus, vertical focus, and segment focus.

Product Focus

Product focus is a potentially powerful sublever for dealing with adaptation challenges because there are often tremendous differences within broad product categories in the degree of variation required to compete effectively in local markets. Compare TV programs, where local offerings generally dominate in most large countries, with films, particularly action films, where Hollywood still dominates because of the more-compelling scale and scope economies associated with big-name stars and special effects. But analysis at the level of films or TV programs as a whole is too aggregated: finer-grained analysis is often required to expose particular challenges or opportunities.

For an example of an action film that traveled particularly poorly across borders, remember The Alamo—the 2004 movie, not the nineteenth-century battle between Mexican forces and Texan rebels. This film certainly met the big-budget criterion—it cost Disney nearly $100 million. It did not generate commensurate book office receipts in English. But what was really remarkable about it was Disney’s attempts to create cross-over appeal for Latinos by, among other things, striving for a more balanced treatment of Anglos versus Mexicans, prominently featuring Tejano folk heroes in the film, running a separate Spanish-language marketing effort, and so on. The point is that no matter how well these tactics were executed, the effort was unlikely to work, because the Alamo is, in the words of one authority, “such an open wound among American Hispanics.”17

Conversely, there are some TV programs that do cross borders rather successfully. Discovery Networks, which focuses on factual programs, particularly documentaries, provides an excellent example. As founder John Hendricks once commented, “Nature and science documentaries are one of the few programs that can be run in almost any country because there’s no cultural or political bias to these programs.”18 In addition, dubbing or subtitling requirements are minimal, especially for nature documentaries. That is not to say that no variation is required: tastes do differ, even in documentaries, with East Asians, for instance, reported to have a predilection for “bloody animal shows” and Australians for forensics. As a result, about 20 percent of Discovery’s programming is local. But compared with other kinds of TV programming, these are relatively minor problems, which is why Discovery and its affiliated networks (including the Learning Channel, Travel Channel, and Animal Planet) report reaching a cumulated total of 1.4 billion subscribers worldwide.

Geographic Focus

Geographic focus is another powerful sublever for reducing requisite variation. The deliberate restriction of geographic scope can permit a focus on countries where relatively little adaptation of the domestic value proposition is required—as well as raising the odds of success by permitting managers to concentrate their adaptation efforts on a particular part of the world. Focusing on the home region is a particularly popular expedient: the majority of the top ten competitors in major home appliances have a clear focus of this sort. Such a regional focus not only minimizes geographic distance and the problems of coordinating across time zones, but can also reduce administrative distance, given the large number of regional trade and investment pacts, and even cultural and economic distance, given greater homogeneity across these dimensions within rather than across regions in many cases.

The use of regions as building blocks of global strategy—with more of an emphasis on multiregional strategies—will be dealt with in detail in chapter 5. But two points do need to be mentioned in the interim. First, geographic focus aimed at tapping commonalities can also take forms other than focusing on one’s home region. Thus, when the Spanish economy opened up in the 1980s, the Spanish focused on investing heavily in Spanish-speaking Latin America as a “soft target” rather than in their “home region” of Europe. Second, geographic focus can be helpful even when a company’s international strategy emphasizes exploiting differences rather than similarities. Thus, Cognizant, a software services firm discussed in more detail in chapter 7, emphasizes India-based arbitrage like many others, but has sought to differentiate itself by cultivating more of a local face in going to market—an adaptive task aided greatly by its focus, until recently, on the United States.

Vertical Focus

In addition to adopting a product or geographic focus, companies can focus on particular vertical “value slivers” and thereby greatly simplify their cross-border operations. Thus Sadia, Brazil’s largest pork and poultry processor and producer of convenience frozen foods, started off by exporting raw meat—eventually becoming the world’s largest chicken exporter—before moving downstream into frozen and processed foods subject to more cultural variation.19 And Brunswick, the U.S. leader in recreational boats and boat engines, tested the international waters, so to speak, with engines before starting to sell boats overseas, with a focus on the premium segment.

Segment Focus

Brunswick continues to focus on exporting premium boats as a way of overcoming geographic distance and associated shipping costs. Zara, the apparel retailing chain from Spain, provides another example of segment focus. Zara has managed to expand into 59 countries and routinely earns returns on capital employed in excess of 40 percent despite standardizing not only its product line, but also the look and feel of its stores, down to the level of window displays, store layouts, and in-store music and perfumes. This reflects its focus on fashion-sensitive consumers, who are arguably more homogenous across countries than fashion-insensitive ones. (Also important, of course, is a strategy that can break even with a few tenths of a percentage point of the total local apparel market.) And companies as diverse as Indian packaged foods suppliers and Mexican media operations have penetrated the United States by focusing on their respective expatriate communities, thereby limiting the need for adaptation. While such “diasporic” communities tend to be small, they also tend to be richer than their counterparts at home, which can make them a profitable target.

Externalization to Reduce the Burden of Variation

The lever of externalization is related to the lever of focus. However, instead of simply narrowing scope, externalization purposefully splits activities across organizational boundaries to improve organizational effectiveness by reducing the internal burden of adaptation. Externalization subsumes multiple sublevers, of which we will focus on four: strategic alliances, franchising, user adaptation, and networking.

Strategic Alliances

Strategic alliances can provide access to local knowledge that would be hard to purchase, to links in the local value chain that would otherwise be inaccessible, or to local connections, including political ones, and associated benefits. Such alliances are used particularly in entering markets that are distant from one’s home base.20 In addition, they can reduce certain kinds of risks by permitting an acquisition in stages rather than all at once (as in the Whirlpool and Philips case), for example. Of course, strategic alliances also impose their own costs and risks, including financial insecurity, lack of control, and misuse of intellectual property.21 For these reasons and because of their managerial complexity, alliances must be treated as a possible sublever for reducing the burden of adaptation and not, as enthusiasts would have it, as a panacea.

Given this complex of factors, many alliance successes—and failures—reflect the luck of the draw. But there are exceptions, of which perhaps one of the most notable is Eli Lilly’s use of alliances to overcome technological as well as CAGE-related dimensions of distance.22 In the late 1990s, as the pharmaceutical industry was engulfed by a wave of mergers and acquisitions, Lilly opted, instead, for an alliance-based strategy. The trouble was that external surveys placed the company’s capabilities in this regard toward the bottom of its peer group. To become first-in-class, Lilly invested in creating an Office of Alliance Management alongside its five business units, setting up a standardized management structure for its hundred-plus alliances, developing a systematic training program and an alliance management toolkit (including a database that codified what it had learned from each alliance), and instituting an annual survey of the health of each of its alliances. One notable success has been the global strategic alliance with Takeda of Japan, which resulted in the rapid rise of the Japanese company’s antidiabetes drug, Actos, to blockbuster status in the United States. The success of this alliance also resulted in a general shift in Lilly’s reputation, toward partner of choice.23 Furthermore, the alliance effort is now in its fourth generation of leadership, indicating that it has some staying power.

Franchising

A similar logic applies to other formal interfirm collaborations. Since I have already introduced the example of Yum! Brands, I’ll use it here as an illustration. Like most other fast-food chains, Yum! has developed a sophisticated franchising operation that shares knowledge extensively in both directions—that is, to and from headquarters. This “plural” form of organization exhibits significant complementarities between franchised and company-owned units.24 Franchising helps the chains relax their internal resource constraints on growth, increase local responsiveness, achieve innovation—it was franchisees that invented McDonald’s Big Mac and Egg McMuffin, for instance—and inject, through voluntarism, some reality checks into their decision making. Company-owned units, in contrast, relax the constraints on growth due to the dearth of qualified franchisees, can be commanded instead of having to be coaxed at every juncture, and supply a basis for building franchisee confidence (e.g., by rapidly rolling out a new idea among company-owned units). Also, mutual learning between the franchised and company-owned units seems important but requires coordination through mechanisms such as cross-cutting career paths and ratcheting (the use of one type of operation to set standards for the other).

User Adaptation and Networking

Going even farther out on the spectrum of externalization, one can think of involving customers and other ostensibly independent third parties in the challenge of adaptation. Various recently emphasized approaches to doing so include lead-user development, “mashups,” and “innovation jams.”25 Perhaps the ultimate example along these lines is provided by Linux, one of several initiatives to develop open-source software—in this case, a computer operating system. The brainchild of a Finnish programmer named Linus Torvalds, it has emerged as a powerful international challenger to the Microsoft operating system. But don’t go looking for Linux’s corporate equivalent of Microsoft’s headquarters at Redmond: Linux is a loosely coupled network based on the efforts of individuals and companies around the world.26

How does something like this work? Roughly as follows: Torvalds sets broad guidelines for the next generation of improvements to Linux. Contributors, by several measures mostly non-American, send their proposed code refinements to Torvalds and his key lieutenants, who either approve or disapprove of their inclusion in the core of the operating system. Then, individual developers are free to embroider on that core to come up with distinctive software offerings. And, in addition to these user-innovators, Linux gets support around the world from a network of specialist firms—Red Hat (United States), Suse (Germany), TurboLinux (Japan and China), Conactive (Brazil), Mandrake (France), Red Flag (China)—as well as complementors such as IBM, which see Linux as a way of combating Microsoft.

Linux is an unusual model—not even a “business” in the traditional sense of the word—but it has yielded an operating system that, in many respects, is much more adaptable than Microsoft’s proprietary code. In addition to being customizable by users, Linux’s kernel (developed by Torvalds and based on Unix) is designed to be scalable so that it can drive devices ranging from wristwatches to computers. Furthermore, Linux does not arouse the same administrative concerns aroused by Microsoft’s code (which the Chinese government, among others, fears is riddled with trapdoors permitting espionage) and, since it is free, is affordable by all.

Design to Reduce the Cost of Variation

The Linux example also hinted at the importance of design as a way of deliberately reducing the cost of variation rather than the need for, or the burden of, variation. Common, interrelated ways to reduce the cost of variation include flexibility, partitioning, platforms, and modularization.

Flexibility

Flexibility is the idea of deliberately designing business systems so as to reduce the fixed costs associated with producing different varieties. The major home appliance industry again provides a good example, as it encompasses two very different manufacturing paradigms: large, vertically integrated U.S. plants that concentrate on long runs for the relatively homogenous North American market, and smaller, less integrated plants that cater to European demands for greater variety. Large U.S. manufacturers typically strive for scales of 1 million units per product at their plants, a level up to which early studies suggested there might be significant economies of scale. In contrast, the more progressive European appliance manufacturers have traditionally placed more emphasis on absolute cost reductions rather than on scale, by designing plants to be comparatively more efficient at short run lengths with aggregate annual scales of one-half to one-third of the larger U.S. plants.

While this home appliance example focuses on production, the potential for flexibility has also been increased recently—for some industries and products—by changes that reduce the costs of inventory storage and distribution. Thus, it has been estimated that consumer benefits from the increased product variety in online bookstores are ten times larger than their benefit from access to lower prices online.27 The Internet is, of course, what has unlocked these sources of value by providing access to a “long tail” of products.28 Amazon, for example, stocks only a very small fraction of the 2.5 million titles that it purportedly offers, relying instead on orders from publishers and distributors to meet demand for the rest after consumers click in their orders. And note that available variety—and adaptability—might be further enhanced by e-books or print-on-demand publishing, in which storage costs are not just reduced, but virtually eliminated.

Partitioning

Partitioning can occur at multiple levels, but at its simplest, it involves clearly separating elements that can be varied across countries from elements that are integral parts of a complex system and that should therefore not be tampered with on a piecemeal basis. While this may sound rudimentary, it is a stumbling block for many organizations. Thus, it took Wal-Mart years, according to its vice chairman, John Menzer, to figure out “bandwidths of responsibility,” namely, the zones within which local managers could make decisions without involving the corporate staff back in Bentonville.29

McDonald’s is generally acknowledged to be a master at partitioning. Consumers, particularly in the United States, often think of McDonald’s as a relentlessly consistent purveyor of Big Macs and the like. But if one has the appetite to visit the company’s outlets around the world, it is obvious that its product offerings vary widely from country to country. To cite just a few Asian examples, McDonald’s offers the Burger McDo (a sweeter burger) and McSpaghetti in the Philippines. (And no, McSpaghetti does not show up in its Italian outlets!) It sells a Teriyaki McBurger in Japan, as well as “lamb-burgers” in India to avoid offending Hindu sensibilities. In Taiwan, McDonald’s launched a rice burger—involving two lightly toasted and flavored “rice patties” rather than conventional buns—in 2005, and started rolling it out in China in 2006.

Such one-off alterations to a system still known for extreme operating efficiency and consistency clearly require McDonald’s to split choices into those where local adaptation is feasible and those where such adaptation would compromise system performance—following a roughly 20 percent local, 80 percent global rule in this regard. But such partitioning extends beyond the choice of products. Thus, although McDonald’s runs global advertising campaigns, its mascot, Ronald McDonald, promotes McDonald’s wine in France and McDonald’s Filet-o-Fish in Australia—and celebrates Christmas in Northern Europe and the Chinese New Year in Hong Kong—but never appears in globally accessible media.30 The idea is to weave the mascot’s story into local cultures around the world.

Platforms

The next frontier for McDonald’s, as of this writing, is to introduce a modular kitchen capable of preparing more than one type of meal in the same restaurant, based on a “combi oven” that can cook several varieties of dishes at once, in a way that will further expand variety at its restaurants.31 (Look in various parts of the world for tilapia sandwiches, McRoaster potatoes, and flautas.)

The combi oven is one example of a platform that underlies cost-effective customization. Indesit, in the home appliance industry, offers another good example. Insiders attribute much of Indesit’s superior performance to its ability to simplify its offerings to one or two basic platforms per product category that can be elaborated into hundreds of different SKUs. Indesit’s discipline in this regard can be contrasted with Whirlpool’s. Whirlpool also pursued platforms—but much more superficially—in a way that concentrated on procurement cost savings instead of making deeper changes to the organization. As a result, the savings that it identified from reducing its product platforms from roughly twenty times the number at Indesit to ten times came to just 2 percent of sales—insufficient to boost its performance up to desired levels and, therefore, deemphasized as the overarching strategic thrust in the early 2000s in favor of a focus on innovation.

Modularity

Modularity blurs into platform approaches but, conceptually, involves defining standardized interfaces between all choice elements, rather than just between a platform and the components that sit atop it, so that all choice elements can be mixed and matched.32 This has been, for instance, the approach followed in the design of most computer systems since the IBM System 360 was introduced in the early 1960s—so that different parts of the computer could be worked on independently by separate, specialized groups. Ericsson’s AXE digital switch, developed in the late 1970s at a cost of about $500 million—roughly equal to half the company’s sales at the time—was a breakthrough in modularization that was explicitly designed to address cross-border variation. Since the size of the AXE’s switching matrix could easily be varied, Ericsson sold it in more than one hundred countries around the world.33 And modular products have also been shown to improve performance in the home appliance industry.34

Yahoo! provides an example of the uses and limits of modularity more broadly—in organizational design. The company set up a plug-and-play structure in which more than one hundred individual “properties” were able to pursue particular target sets of customers on a decentralized basis. What Yahoo! controlled centrally were the properties’ interfaces with the external environment, particularly their “look and feel,” the interface between these services and the company’s core directory search platform, and the contractual terms usable in signing content deals with partners. These arrangements led to rapid horizontal and geographic growth for a number of years, but also illustrate some of the risks of a modularization strategy. In a recently leaked memo, a senior executive described the problem in colorful terms: “I’ve heard our strategy described as spreading peanut butter across the myriad opportunities that continue to evolve in the online world [with the] result: a thin layer of investment spread across everything we do and thus we focus on nothing in particular.”35 Specific problems cited include a lack of a “cohesive vision,” the separation of operations “into silos that far too frequently don’t talk to each other,” and a “massive redundancy that exists throughout the organization.” More emphasis on focus as opposed to modularization might have made sense in this case. More broadly, design for adaptability is often purchased at some cost in terms of efficiency.

Innovation to Improve the Effectiveness of Variation

Some of the levers and sublevers discussed above—such as repositioning and design for adaptability—could also be characterized as instances of the last broad lever for adaptation that will be considered in this chapter: innovation. Innovation can sometimes have a global character. For instance, IKEA’s flat-pack design, which has relaxed the constraints of geographic distance and the associated transportation costs, has helped that retailer expand into three dozen countries. But cross-border differences often imply innovation that is somewhat narrower in its scope, as illustrated in this section’s discussion of progressively more radical sublevers: transfer, localization, recombination, and transformation.36

Transfer

One of the advantages of operating in multiple, varied contexts is that experience may yield innovations or insights in one context that can be transferred to others. The case of Cemex’s transferring multiple innovations from one part of the world to another, discussed earlier, is one example. Whirlpool’s introduction of the Duet, a European-designed front-loading washer, in the United States is another. A third example that reminds us that such innovations need not originate in the most advanced or otherwise significant geographies is provided by Disney. Thus, Disney Latin America—which accounts for less than 2 percent of Disney’s total revenues—has, in recent years, been a major source of insights into improving Disney International’s efficiency by sharing services and, more importantly, enhancing customer appeal through alignment of the Disney experience across major business segments. This is precisely because it has to deal with a challenging macroeconomic environment without the benefit of cash flow from a theme park.37

Localization

While transfer often has the flavor of serendipity, localization involves more explicit focus on innovation in a target geography. Take the examples of KFC in China, discussed in chapter 2, and the Indian arm of Unilever. Hindustan Lever is perhaps best known for its extensive distribution network, which penetrates deep into rural India. Other consumer packaged-goods multinationals have good networks as well, but they use them mainly to “skim” the (small) high end of the market. Hindustan Lever, by contrast, has created local innovative capabilities that leverage its network to great effect. Its product innovations include detergent bars for people who wash their clothes manually, toothpaste to be used with fingers instead of toothbrushes (traditional in India), a skin-lightening cream, and a unique shampoo-and-hair-oil product.

Other innovations have addressed the extreme price sensitivity of the Indian market. Examples include low-unit-price packs (e.g., sachets of shampoo), localization to cut manufacturing costs, and the use of advanced technology to coat one side of a soap bar with plastic (so that it will take longer to wear down). As a result of these innovations and many others, as well as the great reach of its distribution network, Hindustan Lever enjoys gross margins of close to 50 percent—return on capital employed has been reported to exceed 100 percent!—in a very price-sensitive market.

Recombination

Recombination involves melding elements of the parent business model with opportunities that arise in new contexts. As indicated at the outset of this chapter, adaptation goes well beyond simply tinkering with an existing product or service to achieve a better fit with a local market. Splicing in a few new “genes,” while still respecting the host organism, can create an interesting new kind of beast.

News Corporation and Star TV came in for criticism in chapter 2, so I should also acknowledge one of their successes: an interesting example of recombination from the late 1990s that is largely responsible for India being the one major success in Star’s portfolio. The example—Kaun Banega Crorepati—may not sound familiar, but it is the Hindi-language adaptation of the show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? licensed from the British production house Celador. Star used the same basic set, music, and rules in the Hindi version as in the original, but decided that the participants, questions, and marketing had to be adapted to local conditions. In particular, it hired the dominant Hindi-language actor of the era, flew him to London to watch the British version of the show being taped, and worked with him to develop key catchphrases that might work in Hindi. Heavy investments were made in marketing as well, which ensured that the debut of the show was a major event in Hindi broadcasting. And while the success of Kaun Banega Crorepati inspired imitators, none fared very well, including erstwhile local leader Zee TV’s attempt to succeed by offering ten times as much prize money. It’s true that any foreign or local competitor could have licensed the show from Celador for the Hindi-language market—as James Murdoch, CEO of Star TV, told me, “We all go to the same fairs.”38 However, Star’s specific knowledge of local viewers’ preferences and News Corporation’s production expertise (which included other game shows) gave it an edge at identifying and investing in what was, in many respects, more an attempt at recombination or hybridization than adaptation, conventionally construed.

Transformation

Transformation is a way in which firms may directly try to reduce the need for adaptation—by seeking to shape or transform the local environments in which they operate—instead of trying, as just discussed, to enhance their abilities to fit in. McDonald’s, by developing markets around the systems that it had built up rather than the reverse, is often credited with being one of the first successful practitioners of this strategy on a global scale. Starbucks provides another interesting example. Although the Seattle-based coffee giant is frequently cited as being in the vanguard of American cultural imperialism, this accusation is a little misguided. Writing in his autobiography, CEO Howard Schultz paints a fascinating picture of his original attempt to recreate an Italian-espresso-bar experience in the United States—right down to recorded opera music and bow-tied waiters.39 Although the opera music and bow ties soon disappeared—in a form of adaptation—Schultz had successfully called forth a clientele for a coffee-drinking experience that was substantially different from that of, say, Dunkin’ Donuts. He had transformed U.S. coffee drinkers, who now expected easy chairs, hip music, and a smoke-free environment to enhance their coffee-drinking experience.

The transformation experience was even more dramatic when Starbucks moved to Japan. The company insisted on exporting the smoking ban that had helped distinguish its American outlets. Skeptics said that this would certainly doom the chain in Japan by alienating the hordes of chain-smoking Japanese businessmen who traditionally crowded Japanese coffee parlors, or kissaten. Instead, the no-smoking policy helped Starbucks Japan, by enticing a female clientele who didn’t frequent the kissaten.

It bears repeating: because Starbucks was able to change local markets even while it was adapting to local conditions, it minimized the extent to which it ultimately had to adapt. Watch out, however, for a tendency to avoid other forms of adaptation by pretending that all situations can easily be transformed. Thus Microsoft, after a decade of making losses in China—where, the company now admits, it might wait another decade or two to make money—has given up on transformation. As one journalist put it, “It’s clear that Microsoft is no longer trying to change China; China is changing Microsoft.”40

Analyzing Adaptation

Many of the examples discussed in this chapter, particularly that of major home appliances, may have suggested that the principal objective of adaptation is to improve the demand curve that a company faces, that is, to enhance volume, willingness-to-pay, or both. But to think broadly about adaptation, it is important to remember the other components of the ADDING Value scorecard as well: influencing one or more of them may be an important objective, perhaps even the overriding one.

Some of the product indigenization efforts discussed in the subsection on localization provide examples of adaptation aimed at reducing costs. On the process side, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) has recently stressed that an interesting way of adapting manufacturing to an emerging market context is by building disposable factories, defined as labor-intensive, dedicated factories designed for temporary mass production.41 Such factories can supposedly be built for as little as 20–30 percent of the cost of a U.S. plant equipped for flexible automation—which has, in many industries, proved very costly—and can achieve comparable reductions in lead times. In addition, while such disposable factories tend to be inflexible in terms of product mix or batch sizes, their advantages in terms of costs, lead times, and reduced exit barriers may in fact make them particularly advantageous wherever uncertainty is high—reminding us that there is more than one way of normalizing risk.

Having stressed the potentially wide-ranging benefits of adaptation, I must add that it can have negative as well as positive effects on multiple components of the ADDING Value scorecard. Issues related to economies of scale, particularly the link between volume and costs, loom particularly large in this context. The reason is that adaptation—and this is the fundamental limitation of this broad strategy—essentially involves sacrificing global scale economies. The sacrifice is apt to be particularly painful when adaptation involves incurring significant country-specific fixed costs in situations where either the size of the market or a company’s share of it is quite limited.

For example, consider L’Oréal going up against AmorePacific in the Korean market for beauty care products. Chapter 2 discussed the array of disadvantages that L’Oréal, along with other multinationals, faces competing against this home-grown leader in Korea. But L’Oréal could address at least some of the cultural disadvantages that seem to be salient by developing products more tailored to Korean skin tones and conceptions of beauty. The trouble is that if it tried to match AmorePacific’s R&D spending—reported to be 3.6 percent of AmorePacific’s sales in 2006—that would, given a market share of less than one-sixth of AmorePacific’s, escalate R&D to more than 20 percent of L’Oréal’s revenues. And, because of its limited local scale, L’Oréal faces an even bigger hurdle in trying to imitate AmorePacific’s door-to-door distribution system—even though that channel is AmorePacific’s single most profitable. Instead, L’Oréal has focused on tapping global economies of scale—particularly through the cachet of being from France—or at least regional ones (e.g., its emphasis on skin whiteners throughout Asia as part of its “Geocosmetics” strategy).

The L’Oréal example is relatively simple in the sense that trying to adapt more to the Korean market would probably hurt the profitability of L’Oréal Korea as well as the company as a whole. The more tricky cases arise when the profitability of a country operation and of the overall corporation point in different directions regarding specific adaptation decisions—as we will see next.

Managing Adaptation

Examples in which countries champion more adaptation than makes sense from a corporate perspective are legion. To focus in on one, consider the case of Royal Philips Electronics, which has crossed borders for more than a century now.42 Poor transport and communications links, protectionism, and the need to create local joint ventures to gain market acceptance led Philips, like many other early European multinationals, to establish a “federal” system of largely autonomous national organizations (NOs). Federalism was reinforced by World War II, which made Philips place its assets outside Continental Europe in independent trusts. After the war, Philips’s management decided to rebuild the company through the NOs, which therefore added design and manufacturing capabilities to their previous focus on adaptive marketing. A second organizational axis of Main Industry Groups (MIGs) was supposed to coordinate product policy, but remained relatively powerless in the face of a cadre of elite expatriate managers—the so-called Dutch Mafia—who championed the NOs’ country-oriented point of view.

As a result, by 1970 Philips operated five hundred plants scattered across nearly fifty countries and was experiencing pressure from competitors such as Matsushita, which had begun to reduce costs by consolidating factories and moving jobs to lower-wage areas. But Philips’s efforts, starting in the early 1970s, to invest more power in the MIGs (which were renamed Product Divisions, or PDs) failed to make much headway. Philips had, by then, developed a “thick” culture: mature, complex, bureaucratic, and resistant to new information and incentives. As a parade of CEOs attempted to rebalance the geography-PD matrix away from the NOs and toward the PDs, Philips continued to lose market share and to restructure by exiting business after business. Finally, in 1996–1997, a new CEO, Cor Boonstra, brought in from the outside, took the drastic step of abolishing the geographic leg of the matrix. More than a quarter-century had elapsed since the first attempts to place less emphasis on adaptation through NOs and more on global economies of scale through the PDs!

In addition to illustrating that it is possible to overadapt, the Philips case shows that the optimal degree of adaptation varies by industry and can change over time, and that there may be—especially in mature organizations—long lags in changing the actual degree of adaptation. The case also has implications for the debate about whether there is one best way of organizing, at least from an adaptive perspective. Specifically, it has been suggested—particularly in Europe—that the European model of companies as multinational federations is inherently superior to the typically more centralized U.S. model of multinationals because of the diversity the former offers.43

The Philips example reminds us that it’s not that simple: if you set up constitutional principles that prevent the adjustment of structures or processes in the face of changing realities, you are setting yourself up for enormous problems. Sometimes power must be concentrated centrally, whereas at other times, it must be dispersed locally. The trick is to concentrate and disperse proactively rather than to treat decentralization—or centralization—as the optimal approach. If we did, we would be back in the straitjacket we saw Coke struggling with in chapter 1.

The broader point is that it is possible to imagine errors of two types: overadaptation and underadaptation. The levers and sublevers discussed in the previous sections help relax the underlying tension between complete localization and complete standardization, but that still leaves open the question of how much to adapt.

Optimally exploiting adaptation possibilities—in a way that avoids the dangers of both over- and underadaptation—requires what might be termed a global mind-set. But this is easier said than done—as managerial self-assessments indicate. Thus, a survey of fifteen hundred executives in twelve large, multinational companies in the mid-1990s asked them to rate their performance along various dimensions deemed vital to international competitiveness. “The respondents rated their ability to cultivate a global mindset to their organization dead last—34th out of 34 dimensions.”44

To make matters worse, what executives mean by a global mind-set often discounts adaptation as a strategy lever. Thus, in another survey aimed at deriving bases for measuring the globalization of mind-sets, the researchers had to add responsiveness-related dimensions themselves because the respondents were apt to overlook these dimensions.45 This presumably reflected a tendency to conflate global mind-sets with standardization and centralization.

What is to be done in the way of remediation? Experts agree that rote learning about the beliefs, customs, and taboos of foreign cultures—for instance, that a thumbs-up is a gesture of contempt in India rather than an indication that everything is OK—will never prepare people for every situation that arises, although it is the approach that corporate training programs often take.46 What are required, instead, are mechanisms for cultivating both openness and literacy about diverse cultures and markets (see the box “Fostering Openness, Knowledge, and Integration Across Countries”), mechanisms that also help with the other strategies for dealing with differences described in this book—aggregation and arbitrage.

Fostering Openness, Knowledge, and Integration Across Countries

Beyond the mere rote learning of discrete facts about foreign cultures, successful adaptation requires a company to employ as many open-ended opportunities to develop literacy about diverse cultures as it can.

1. Hiring for adaptability: People vary in their ability to act appropriately and effectively in new contexts or among people with unfamiliar backgrounds. While training and experience can help in this regard, it is best to start by hiring people attitudinally disposed to mastering such situations.

2. Formal education: Formal education occurs not only in classrooms, but also through interactions with colleagues from other locations around the world. Of course, the appropriate content of such formal education is highly contingent: it would be dysfunctional to emphasize the importance of more localization to Philips’s managers, for instance, and of standardization to Wal-Mart’s, instead of the other way around. When I work out a training program on global strategy for a corporation, I tend to spend more time on design than on delivery.

3. Participation in cross-border business teams and projects: Team and project work can be key in developing interpersonal ties that cross borders—a very important complement to formal authority in getting things done. The coordination of globally distributed teams has been eased in recent years by information technology, which might itself be cited as a key enabler of the creation of high-bandwidth international links.

4. Utilization of diverse locations for team and project meetings: I recently attended a meeting for IBM stock analysts held in Bangalore. As CEO Sam Palmisano explained it to me, this was primarily about signaling commitment to and helping integrate an operation that had grown from less than ten thousand people to close to fifty thousand in three years, and not because IBM’s strategy could be explained only in Bangalore.

5. Immersion experiences in foreign cultures: The Overseas Area Specialist course that Samsung initiated in 1991 is still a role model in this regard. Every year, more than two hundred carefully screened trainees select a country of interest, go through three months of language and cross-cultural training, and then spend a year there—without a specific job assignment or contact with the local Samsung office—followed by a two-month debrief in Seoul.

6. Expatriate assignments: An even more intense form of immersion, expatriate assignments are also very expensive economically and in terms of personal wear and tear. As a result, they need to be targeted at high-potential managers rather than as a way of exiling people whom one would rather not see.

7. Cultivating geographic and cultural diversity at the top: It is still easy to find large companies with significant operations outside their home markets whose top management—and board of directors—is still (almost) entirely domestic. China provides a particularly dramatic example: the number of large Western companies with any Chinese representation at the top is still tiny.

8. Dispersion of business unit headquarters or centers of excellence: P&G’s CEO, A. G. Lafley, regards the company’s geographically dispersed business unit headquarters as a key point of difference from many of its competitors. Of course, the locations must be selected carefully: P&G’s attempt to locate the headquarters of one of its global business units in Caracas quickly ran into problems and had to be revised.

9. Defining and cultivating a set of core values throughout the corporation: A strong one-firm culture can help override parochialism despite the diversity of locations and market conditions. A number of professional service firms provide good examples.

10. Opening up across organizational boundaries: To frame the problem as one of creating openness within the organization is to frame it too narrowly: interest in open innovation, for instance, is a reminder of the gains that can be tapped by opening up the organization to the outside world. Of course, such opening up to the outside also entails risks.

Source: Adapted (and extended) with permission from Vijay Govindarajan and Anil K. Gupta, The Quest for Global Dominance (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001), 129–136.

Even with all these mechanisms in hand, overcoming all the barriers to strategy change may require a major organizational push. The Samsung Corporation offers a particularly dramatic example.47 Despite a number of initiatives over the years, including the immersion program described in the box, Chairman Lee Kun Hee was dissatisfied with the pace of globalization efforts and, in 1993, launched his New Management Initiative by summoning 150 senior executives to a luxury hotel in Frankfurt. He began his presentation to them at 8 p.m. and lectured them nonstop for seven hours about the need to “transform Samsung into a true world-class company”—without once going to the bathroom, according to one participant—culminating in a call to “change everything but your family.” After he finished, he ordered the participants to stay on in Frankfurt for a week as a way of exposing them to the outside world. He took the entire senior management on other trips as well, including to Los Angeles to “show them our actual position was much lower than what we had thought.” The symbolism of these efforts was backed up by a substantive emphasis on quality—and innovation—instead of quantity, which would make it more like Sony. Samsung restructured its portfolio to exit sunset businesses and tripled the percentage of production overseas to 60 percent of the total by 2000, through a program that involved regionalization as well as major acquisitions and strategic investments.

More than a decade later, this Frankfurt meeting is still recalled as having sparked a cultural transformation. Samsung, alone among the major Korean chaebol, not only survived the Asian financial crisis intact, but also achieved more than twice the market capitalization of Sony and overtook the Japanese company—and Philips and Matsushita’s Panasonic—as the world’s most valuable consumer electronics brand.48 The example also reminds us that cultivating openness and literacy about diverse markets and cultures is about the heart as well as the head.

Conclusions

The box “Global Generalizations” summarizes the specific conclusions from this chapter. More broadly, adaptation clearly subsumes a range of different approaches, all of which must be thought through, instead of being a mechanical, paint-by-the-numbers process. The good news is that a comprehensive perspective on adaptation tremendously expands the headroom available to adjust to differences. The bad news is that even with full exploitation of adaptation-related possibilities, adaptation as a strategy for dealing with semiglobalization suffers from two distinct sets of limitations. First, assuming that centralized decisions are made at the global level and decentralized decisions at the local level fails to account for cross-border aggregation mechanisms that operate at levels intermediate to the country and the world. Second, adaptation strategies almost, by definition, treat differences across countries as constraints to be coped with and thereby ignore the possibilities of capitalizing on them. The two types of generic strategies for dealing with semiglobalization that are discussed next, aggregation and arbitrage, explicitly target these two limitations of adaptation strategies.

1. Very few businesses can operate on either a totally localized or a totally standardized basis across borders.

2. There are numerous levers (and sublevers) for adaptation intermediate to the extremes of localization and standardization: variation, focus, externalization, design, and innovation.

3. It is possible to adapt too much or too little—although the latter may be more common.

4. Industry characteristics have a great deal of influence on the optimal degree of adaptation, which may increase or decrease over time.

5. Changing the actual degree of adaptation can be subject to very long lags.

6. Change is aided by a flexible, realistic, and open mind-set—and may require a major organizational push.

7. Most companies have much headroom to improve how they adapt.

8. Adaptation decisions cannot be made independently of decisions about aggregation and arbitrage.