Over the past six years, Dreamweaver has become the standard for building, maintaining, and working with websites. Known for its intuitive toolset, cross-platform–feature parity, and wide range of supported server technologies, Dreamweaver is to web publishing as InDesign is to print. Adobe’s acquisition of Dreamweaver strengthens the platform by combining it with the best graphics tools available.

Dreamweaver makes it simple to construct anything from a single web page to a site consisting of thousands of pages across hundreds of folders. It frees web developers from the drudgery of site management and allows them to concentrate on the creative aspects of site design and information presentation. For the “hardcore” developer that requires hands-on access to HTML, Dreamweaver provides code-level editing and validation that are second to none.

This chapter will cover everything you need to know to create websites in Dreamweaver. We’ll start by defining a new project, then work our way through adding design elements, media, and more!

Let’s get started. Opening Dreamweaver brings up the typical Quick Start welcome screen. Here you can create a new document, open a recently edited page or site, or create a new site from one of Adobe’s built-in templates. If you prefer to use this interface for getting to your files, feel free, but our focus will be on using the standard menu items to access functionality. In fact, if you never want to see the welcome screen again, just click the Don’t Show Again check box.

The New command is conveniently found in the File menu. Don’t let the simplicity of the single word new fool you, though, because Dreamweaver can create a host of document types—everything from XHTML pages with a variety of prebuilt layouts to plain old text (TXT) files. XML, CSS, SMIL, JavaScript, QuickTime, Perl, PHP, MMS, and other Web-related file formats are documents Dreamweaver can handle with ease. This chapter covers only the basic file types, but be aware that Dreamweaver has a depth and breadth beyond what is discussed here.

Also located in the File menu are the Open and Open Recent commands. The Open Recent submenu is especially helpful because it lists not only recently opened sites, but also individual HTML pages and other types of documents you might have opened recently. At the very bottom of the Open Recent submenu is the option Reopen on Startup, which reopens all of your recent files each time Dreamweaver starts up.

When you need to quickly work on a file or two, Dreamweaver can be used in a pinch just by opening the existing file using File, Open, or by creating a new file using methods we’ve just described. Working in this mode too much, however, can lead to problems.

The Web works by linking different pieces of content together. Imagine that you start by creating one page, add in a few images, and then add another page, linking them together. Do this a few more times and you’ve just created a website. Unfortunately, you’re stuck without being able to organize the content. If you move pages into a folder, the links will be lost and you’ll have a bunch of manual cleanup to do just to get things working again.

To get around this problem, Dreamweaver defines the notion of a site. A site is any collection of content that you want to use together on one or more web pages. When pages are created and managed within a site, Dreamweaver takes care of keeping your links intact for you. Move your files to a new folder? No problem—Dreamweaver makes sure your links change appropriately.

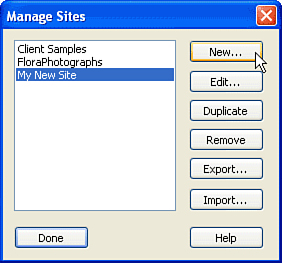

From your computer’s perspective, a site is simply a directory where all of the web files will be created. From the Site menu, choose Manage Sites. Figure 10.1 shows the Manage Sites dialog box.

By choosing Manage Sites rather than New Site, you open a simple manager for all of the sites that you set up on your system. Here you can create a new site, edit/duplicate existing site definitions, import or export sites, and, of course, remove sites. Click the New button and choose Site to start a new site definition.

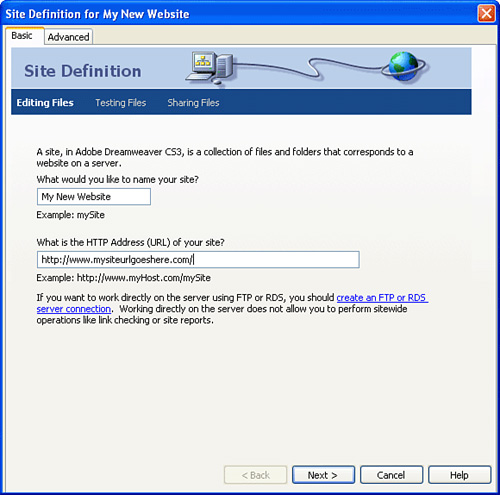

The process of defining a site walks you through a wizard that collects some information about your website. If you aren’t positive of something, you can always go back and edit it later, so don’t worry about it too much. Figure 10.2 shows step one of the Site Definition wizard.

First, decide what you want to name your site, and type it into the Site Name field. This is an arbitrary name that is only used to identify the site to you; it won’t show up on any of the web pages. You are also prompted for the URL of the site. If you don’t yet know, just leave it blank. Click Next to move on.

Dreamweaver now prompts you to see if you want to work with a server technology (to build dynamic database-driven pages). Because this is beyond the scope of this book, choose No, I Do Not Want to Use a Server Technology, and then click Next.

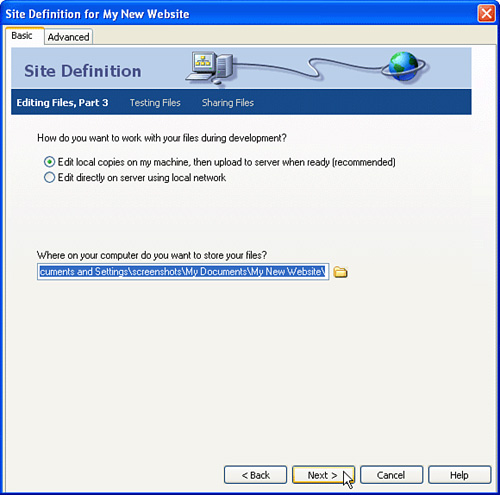

On the third screen of the Site Definition wizard, things get a bit complicated. Here you need to decide whether you’re going to be editing files directly on a connected server volume (a mapped network drive—never a good idea), or locally and then uploading them to a remote server. The local option is what you want, even if you aren’t ready to connect to a server. Click the Edit Copies Locally button, and then click the folder icon to choose where your site files will be saved. After making your choice, click Next, as shown in Figure 10.3.

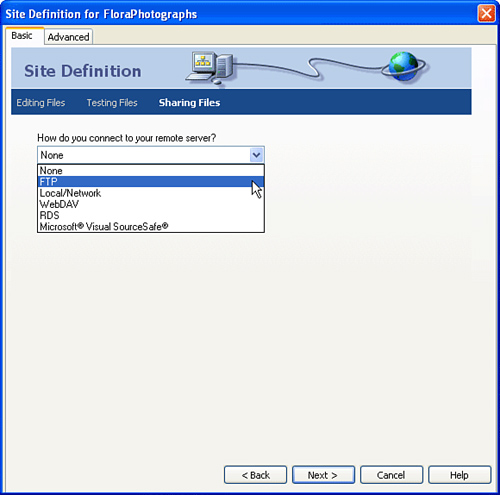

Finally, Dreamweaver wants to know how it is going to connect to a remote server. Choose None, and then click Next.

Your site is now defined. Dreamweaver displays a summary of your settings. Just click Done and you’re ready to start building. Any new pages you create will be added to and managed within this site definition.

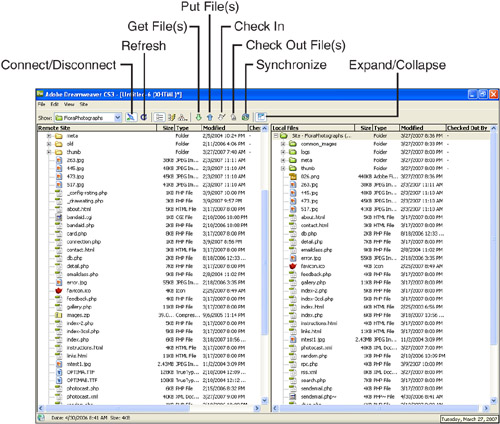

After you’ve saved one or more site definitions, you can view the contents of the site from the Files panel within the Files panel group, as seen in Figure 10.4. This presents a Windows Explorer–like view of the files that are currently available within your site. If you have multiple sites defined, switch between them quickly using the pop-up menu in the upper-left corner of the panel.

After your site is selected, you can double-click files to open them, drag them to move them, and so on. New files and folders can be created directly within the panel using the Files panel groups flyout menu (the upper right corner of the group panel) or by right-clicking in the file listing. It’s a convenient way to organize things without having to leave Dreamweaver.

The best thing about the Site Files view is that it is an “intelligent” means of managing your files. Unlike the file system on your computer, when you drag a file from one folder to another in your site, the Dreamweaver CS3 file manager understands that this move might have consequences. It automatically scans through your documents and makes sure that any links to or from the document being moved will still work. With these conveniences (and others you’ll learn about later), you’re likely to find that this panel quickly becomes one of your most frequently visited screens.

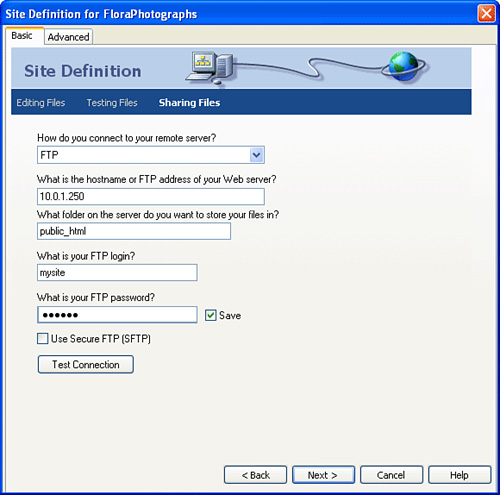

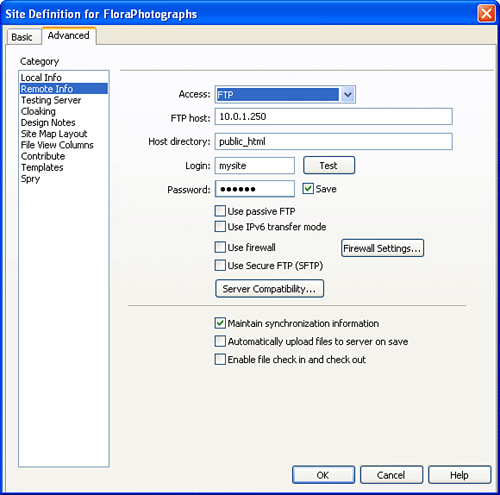

Unlike GoLive, Dreamweaver does not have an official site import feature, but it is still very easy to do. To import an existing site that is located on a remote server, you configure your site definition as you did earlier, but you specify the full details of the connection to your remote server in the Sharing Files area of the Site Definition dialog box.

When a site definition has a remote server attached, you can copy the files from the remote server into your local site definition using, you guessed it, the Files panel. We’ll look more closely at this in the “Transferring Files to and from Remote Sites” section later.

As you work with your CS3 suite, you’ll appreciate the similarity between the different applications. Dreamweaver, as you’ve seen, has a main window (where you’ll do your web page composition) as well as a number of different panel groups, each containing panels that provide additional features. Chances are, you aren’t going to use all of these all the time, but it’s good to get a sense for what there is, and where it is. Let’s explore the Dreamweaver CS3 workspace now.

To begin, let’s create a new blank document by clicking “Create New... HTML” from the Welcome window, or by choosing File, New, HTML from the menubar.

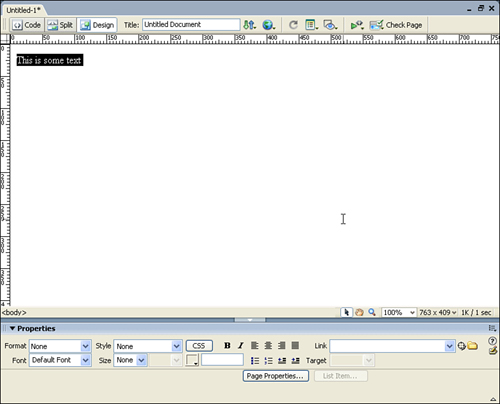

When you start Dreamweaver CS3, the largest area on your screen is the Document window. This is where you compose your web pages in the What You See Is What You Get (WYSIWYG) interface. As you build your page, you’ll immediately see the results of each change, just as it would appear in a web browser.

Three parts make up the Document window. The top of the window contains the toolbar, which holds shortcuts to many common commands and functions (you’ll learn about these as needed). If you open multiple documents in Dreamweaver, they’ll open in separate tabs also located along the top of the window (just like most popular web browsers). The middle is the content area, and the status bar is at the bottom.

The Document window is where you will do most of your web page editing. To add to your page layout, you can type directly into the Document window or use the Insert panel or Insert menu to add text, graphics, or links to the page. The flashing cursor in the Document window shows where the current insert point is located. You can move this point by clicking with your mouse or using the arrow keypad to move it around. Wherever the cursor is, that’s where your text or object will be inserted.

Anything that has been added to the Document window can easily be removed, cut, copied, or pasted—much like your standard word processing software. You can select text by clicking and dragging your cursor over the letters. To select an object such as an image, click it once. You can choose multiple items by moving the insertion point to the beginning of the group of objects you want to select, and then holding Shift and clicking where you want the selection to end. Single selected objects are designated by a darkened outline, whereas multiple objects are darkened completely.

After an object is selected, you can use the Copy, Cut, Paste, and Clear commands under the Edit menu to move, duplicate, or delete the selection. The Backspace key also works in a pinch to delete a selection. Two additional copy-and-paste methods are located in the Edit menu—Copy HTML and Paste HTML. These are rather counterintuitive operations that might not perform exactly how you’d expect. As you might know, HTML is the underlying language that forms web pages. Simple tags define the way a page looks when it is presented in a browser. Each tag usually has a start tag and an end tag to define what a particular style applies to.

For example, the bold tag is used to make text appear bold in your web browser. In the following sentence, the word bold is defined using HTML tags to appear in a bold typeface onscreen:

I like to emphasize words with <b>bold</b>.

The Copy HTML selection will copy the underlying HTML behind what you see onscreen. You can then paste the HTML into other applications. If you simply used the Copy command, you’d end up just pasting the text version of what you see onscreen.

Paste HTML works similarly with the Paste operation. If you’ve copied HTML code from another program, you can use the Paste HTML function to paste it into Dreamweaver with all the styles intact. The standard Paste operation would end up pasting the HTML code itself. A good rule of thumb is to use these special forms of Copy and Paste only when working with external programs; otherwise you might find the results confusing. The tags themselves will be pasted as part of the onscreen text, rather than being recognized as HTML.

Dreamweaver has provided several shortcuts that make selecting objects even easier. To select a line of text or an object, click in front of the object near the left window border. The cursor changes to an alternate arrow style to show that it is in the line-select mode. You can extend this technique to select multiple objects by clicking and dragging down the left border of the screen.

At the bottom of the Document window is the status bar. This provides a few simple controls for interacting with the document view.

The left side of the status bar contains a listing of the HTML tags surrounding the current cursor position. As you work with more complex web page designs, you’ll appreciate how quickly this can help you determine exactly where you are in the document.

Another component in the status bar is the current size of the Document window in pixels (width × height). As you’re almost certainly aware, websites often are designed without any attention paid to the size of the screen on which they will display. You can quickly set several preview sizes by clicking and holding on the display of the current window size in the status bar. A pop-up menu appears with a list of common preset sizes that you can choose, including the maximum window size for WebTV viewers.

On the far right of the status bar is an estimation of the page size and the time it will take to download. Most site developers target a particular class of user—dial-in/DSL/LAN browsers, and so on. Creating beautiful pages that take 10 minutes to download is not a good idea. The default speed that is used to estimate the download time is a 56kbps modem. You can adjust the speed in the Dreamweaver status bar preferences, accessed by pressing Command-U (Mac) or Control-U (Windows).

The final portion of your document area is the toolbar. Located directly above the Document window itself, the toolbar contains quick-click shortcuts for switching between HTML, split HTML/Design, Design, and several preview modes, as well as a very convenient way to set the title of the current document and validate that the document is made with correct HTML. You’ll learn more about these features later in the chapter.

Arguably, the most important of the myriad of Dreamweaver panel groups on your screen is the Insert group. This is a floating window that appears above your Document window. As you design pages, you’ll frequently refer to this panel, shown in Figure 10.5, and its toolbox of web elements.

Looking at the Insert panel, you’ll see several categories of elements that you can work with, represented by tabs. In its vertical orientation, the tabs are replaced by a single pop-up menu at the top of the panel. Using either the tabs or the pop-up menu, you can access these types of tools:

Common—. This is the most common of the design elements. This includes images, tables, embedded objects, and composite constructs such as navigation bars and image rollovers. This is the default palette shown.

Layout—. Tables, layers, and other elements for creating complex page layouts.

Forms—. Text fields, radio buttons, and everything you need to put together input forms.

Data—. When creating dynamic websites, this panel contains several tools for tying into databases and accessing other server-side features.

Spry—. Elements that use Adobe’s Ajax (JavaScript) features to create dynamic onscreen effects, such as collapsible lists, sorting tables, and so forth.

Text—. Common text formatting features, such as headings, paragraphs, and lists.

Favorites—. Right-clicking when Favorites is selected allows you to customize this panel with any of hundreds of available shortcuts, including those from any of the other Insert panels.

Each element that you add to a web page, be it image, text, or any other object, has properties that can change how it looks in a web browser. Text can be set to certain colors; images can be altered to different widths or heights. Rather than create a different configuration dialog box for each object that you can edit, a single panel, called the Properties panel, handles everything. Located under the document area, this panel is context sensitive. Whatever item is currently selected in your design can be configured through the Properties panel. As you switch from one element to another, the contents of the Properties panel update automatically. Try, for example, selecting some text that you’ve typed into your document design window. Figure 10.6 shows the properties for basic page text.

The Properties panel itself has a few different modes that can be activated depending on the level of detail with which you want to work. If you’re a beginner, you might want to view the Properties panel in the simple mode. To do this, collapse the window to its smallest size by clicking the up arrow in the lower-right corner of the window. If the arrow is pointing down, the window is already collapsed, and clicking the arrow toggles the window into expert mode, providing several additional options.

If you don’t have a perfect encyclopedic memory of HTML tags, you can access an extensive help system in the Properties panel—just click the Help icon located in the upper-right corner of the Properties panel. This launches the help system and displays information about the attributes you are editing. You’ll find this is an excellent way to get context-sensitive information about an object without resorting to a reference manual.

Another useful feature of the Properties panel is the Quick Tag Editor. Clicking the button directly below the Help button launches the Quick Tag Editor. The Quick Tag Editor simply brings up a pop-up window that contains the HTML for the tag being edited. You can change any of the HTML in the tag directly. Although this might not seem like a very big feature, sometimes you know exactly what you want to change on a tag, but you don’t want to search through the source code or deal with going through an interface to find it. The Quick Tag Editor gives you exactly what you want and doesn’t force you to use the point and click tools to make your changes.

The other panels used in the Dreamweaver CS3 environment are important, but will not be as heavily used as what we’ve seen to this point. To get a sense for what other tools are available, let’s review the panel groups and the panels they contain. Keep in mind that you can rearrange panels and panel groups. So if your system doesn’t match exactly, someone has probably been customizing things a bit. You can revert back to the default layout by choosing Window, Workspace Layout, Default from the menu.

Not all panel groups are visible initially. If you don’t see one of the groups listed here, look under the Window menu.

The Application panel group contains these tools:

Databases—. Databases provide the information used inside a dynamic site. The Databases panel is used to define and view databases connected to the current site.

Bindings—. Defines and edits connections to live data sources (for instance, databases).

Server Behaviors—. Also necessary for dynamic sites, Server Behaviors control how information is processed by the remote web server.

Components—. Used to add JavaBeans or web services to the application. This panel is mainly of use to advanced developers.

The Frames panel group contains this tool:

Frames—. If you’re creating a website that uses frames, you’ll probably want an easy way to control them. The Frames panel lets you select and modify individual frame attributes.

The Files panel group contains these tools:

Files—. The Files panel contains the tools you need to keep track of your website’s files and synchronize them with remote servers.

Map—. Although part of the Files panel, the Map is an entirely separate tool, accessed from the flyout menu. One of the hardest parts about maintaining a site is keeping track of how the pages connect and the paths that the users can take to reach different pieces of information. Dreamweaver can generate a map of your website for easy reference.

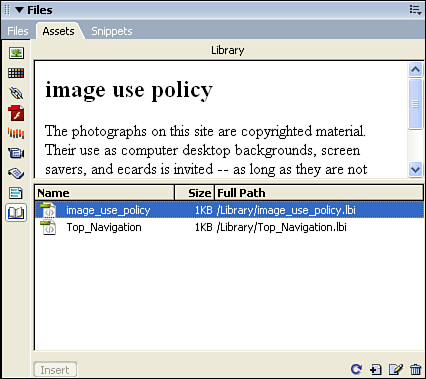

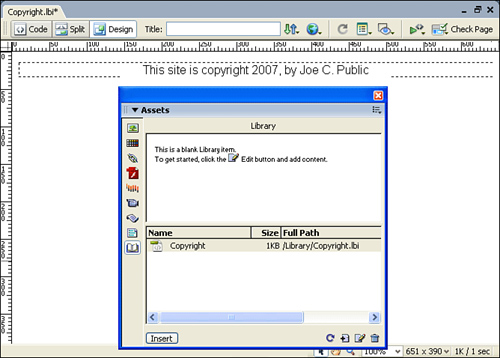

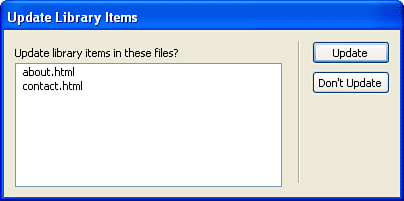

Assets—. Site assets are all the images, colors, and other objects in use on your site. You do not need to manually create the Assets panel—Dreamweaver will update it for you. The Assets panel is an excellent way to keep track of everything on your site.

Snippets—. The Snippets panel holds small code fragments that you can use with your site.

The Tag panel group contains these tools:

Attributes—. A hierarchical list of all the attributes that can be set for your HTML tags and styles.

Behaviors—. The Behaviors panel is used to add JavaScript actions to objects on a web page. The behaviors are generated automatically, without any need for knowledge of the JavaScript language.

The Timelines panel group contains this tool:

Timelines—. Through the use of JavaScript and layers, portions of a web page can be animated over time. The Timeline panel enables you to visually set the position of layers against time.

The CSS panel group contains these tools:

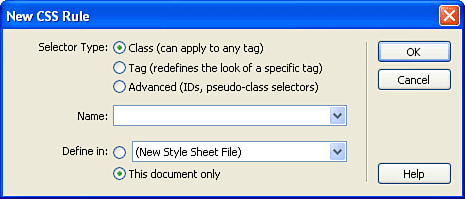

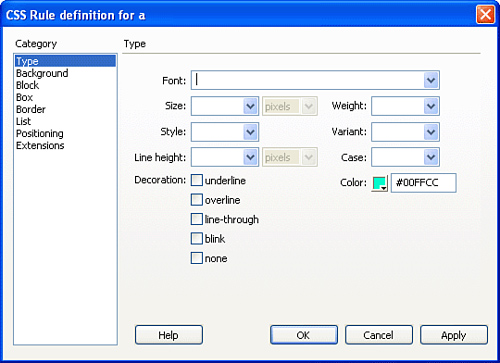

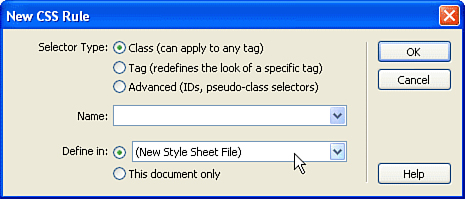

CSS Styles—. Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) are the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) standard for controlling the look and feel of your website down to the pixel size of the font being used and the margins around your elements. This panel contains all the defined styles and allows you to edit and apply them.

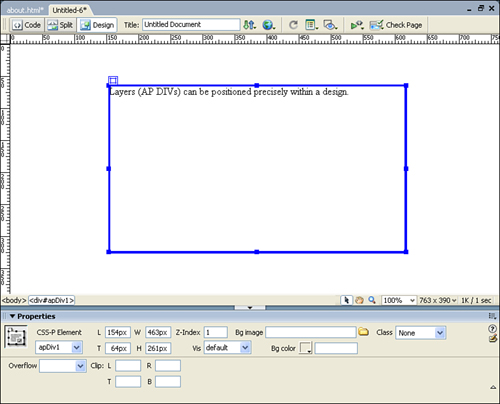

AP Elements—. Lists and allows selection of any absolutely positioned (AP) elements. AP elements can exist on top of one another or even be entirely invisible. As such, it’s often difficult to find what you want to edit. The AP Elements panel shows you a list of all these items in one place.

The History panel group contains this tool:

History—. If you’ve used History to fix some boo-boos in Photoshop, you’ll recognize the History panel immediately. The History contains a list of all the changes you’ve made to the web document. You can immediately back up to any state that the document has been in since it was last saved. The history can hold between 2 and 99,999 steps, with the default being 50. You can reset this value in the General section of the Dreamweaver preferences (Command-U or Control-U).

The Results panel group contains these tools:

Search—. Conducts a search on the entire site, identifying the matched files in the panel.

Reference—. The Reference panel is an extremely detailed reference for CSS, HTML, and JavaScript. If you’re interested in the technology behind the code you create, everything you need to know is right here.

Validation—. Want to see how close your documents are to true HTML standards? Using the Validation panel, you can check for how well your document validates against popular web standards. Not many web pages are fully standards compliant, but it’s a good goal to have.

Browser Compatibility Check—. No matter how well your document follows web standards, it may still have problems in certain browsers. The browser compatibility check identifies potential problems before your site is launched.

Link Checker—. The link checker automatically scans your entire site for broken links. Any identified errors are found and presented for correction.

Site Reports—. Site Reports runs a series of tests on your website looking for problems, as well as identifying what editors are currently working on files.

FTP Log—. Need to check on FTP file transfers to and from your site? This panel might help your diagnose connection errors.

Don’t think the panel layout is ideal for your particular needs? No problem—you can rearrange everything in Dreamweaver CS3.

You can collapse panel groups into a single line or expand them to show the entire panel by using the disclosure arrow in front of the panel name. These groups are then listed as part of the complete panel collection, usually located down the right side of your screen. You can break the collection into smaller groups by clicking on the dotted drag handle in front of the group name and dragging the group out of the main collection. Dragging the group back to the main collection will add it back to the list.

If you want to take things even further, you can drag individual panels from one group to another to create new hybrid groups. Clicking the pop-up panel menu button at the top-right corner of each panel provides additional features for renaming groups, maximizing panels, closing group panels, and special functions for the frontmost panel.

To clean up your view quickly, you can deselect individual panels under the Window menu or use the View, Hide Panels (F4) command to hide all of them at once. If you’re more interested in arranging things neatly rather than hiding them, choose the Tile or Cascade options. Dreamweaver will attempt to arrange the floating windows as best it can.

You’re now ready to start creating and editing basic pages. To begin, make sure that you have a site created and selected.

To create a new page, choose New from the File menu. The Category selection allows you to choose between blank documents, templates, and stationary. You want to start with a Blank Page, so be sure that it is highlighted. Next, in the page type list, pick HTML. If you want to use a predefined page layout, select an option from the Layout column. Finally, click the Create button.

Your new document will open in the workspace. (You could also create a new file in the Files panel using the Files panel menu or contextual menu, as mentioned earlier.)

You should now have a blank HTML document open in your editor, waiting anxiously for content.

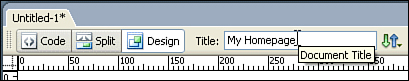

When you make a new page, Dreamweaver CS3 automatically puts the words Untitled Document in the Title field. This will appear at the top of the browser window when the page is viewed and will also be used as the default bookmark name should your visitors want to come back later.

Before adding anything to the body of your page, you’ll want to change these words to something that better indicates the content you expect to be in the page. Click the Title field at the top of the page to select the default title, and then simply type in the new title (see Figure 10.7).

With your title in place, you’re ready to begin building your page. You’ll have your choice of several editing views. Let’s take a look at the editing views and how they are used.

Not everyone approaches building a web page the same way. Some people have visual minds and like to work as they would in a page-layout application. Other folks prefer to hand-code their HTML. Fortunately, Dreamweaver has a set of tools to satisfy everyone.

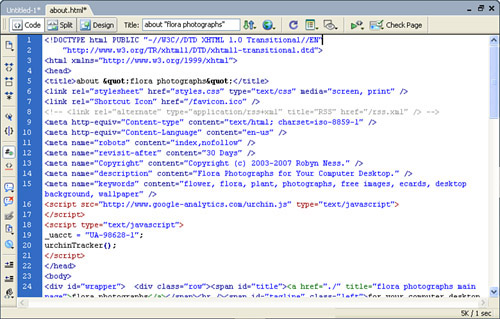

When editing HTML, you’ll notice three buttons in the upper-left corner of the editing area (Code, Split, and Design). Those buttons represent the various page-editing views (see Figure 10.8). Each mode has unique features, so you will probably find yourself using a combination of editing views as you become more experienced with the application.

There are several controls along the top of the editing window that you can make use of at any time regardless of the editing view that you are in. You’ve already seen the Title Editor; each of the other buttons hides a pop-up menu with several features. Let’s review these buttons now, from left to right:

File Management—. After you’ve configured your site definition with a server for deployment, you’ll be able to use these buttons to send the file you are working on to the remote server, fetch files from the server, and more. You can do all of this from the Files panel as well, but this button is a convenient shortcut.

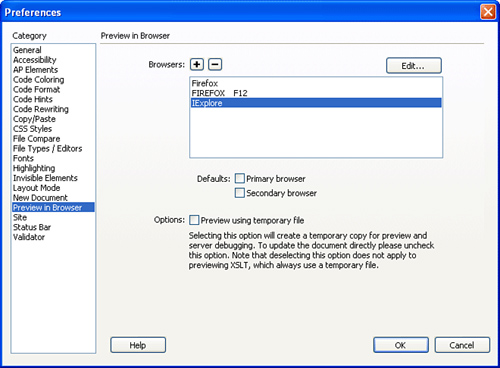

Preview/Debug in Browser—. Dreamweaver uses a real embedded web browser engine to display your documents in real-time as you create them, but obviously this is only one potential view and there are half a dozen browsers that you might want to check your creation in. The Preview button will allow you to view the current page in any browser on your system. If a browser is now already in the list, just click the button and choose Edit Browser List to easily edit the available browsers, as shown in Figure 10.9.

Refresh Design View (Design/Split)—. If you’ve made a change to the code that isn’t being reflected yet in the Design or Split views, click this button to force Dreamweaver to update the screen.

View Options—. The View Options button opens a menu that displays several settings that are specific to the view in which you are working. In Code view, for instance, this button can turn on and off line numbers and word wrap. In the Design view, it shows and hides tools such as rulers and grids.

Visual Aids (Design/Split)—. When working in one of the visual modes, these settings are used to activate the display of elements such as table borders and visual displays of width and height values—pieces of information that are helpful, but might be distracting when trying to view your designs onscreen.

Validate Markup—. Checks to see if the code in the document is valid according to the type of document you are creating (HTML, XHTML, ColdFusion, and so forth). If you’re only using the design tools, your documents should always validate because Dreamweaver will obey the appropriate standards. If you’re coding by hand, however, there might be errors introduced into the code. This is the tool that can help you find them.

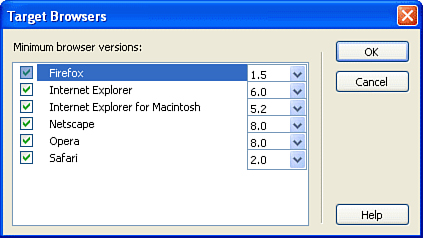

Check Page—. One of the most useful features of Dreamweaver CS3 is its capability to check your page against a variety of browsers to find common problems. Using the Settings command, which displays the Target Browsers dialog shown in Figure 10.10, you can configure the versions of the various browsers that will be tested.

Now that you know what the common controls are for, let’s review the different views available and the features specific to them.

Code view is where the HTML code that makes up a page is visible. The code is fully editable, and changes made here are reflected in the other modes. Dreamweaver’s Source Code Editor is very powerful, with features such as code formatting, element collapsing, and code completion. If you’re in raw HTML, as seen in Figure 10.11, this is the place to be.

Down the left side of the window, you’ll find several tools specific to this mode:

Open Documents—. Choose which source code file you’re working on if you currently have several open.

Collapse Full Tag—. If you’ve spent time working with HTML, you’ll know that tags generally come in pairs. For example, a document’s title and page description can be found with the

<head>and</head>tags. Sometimes you don’t necessarily need everything in between the tags to be visible onscreen. By clicking inside a tag, such as<head>, and then activating this tool, it will collapse the tags into a single space-saving line.Collapse Selection—. Just like the Collapse Full Tag tool, this feature collapses multiple lines of text into a single line. This variation, however, collapses any group of lines you select, not just a pair of tags.

Expand All—. Expands all of the currently collapsed tags and selections so that all code is visible.

Select Parent Tag—. Selects the text between the parent tag of a given tag. The

<title></title>tags, for example, are children tags of the<head></head>tags. If you use this tool while your cursor is in the<title>tag, it automatically selects everything in the<head>tag set.Balance Braces—. Often, when programming or using CSS, you’ll need to use braces

{}to start and stop blocks of code. If you’re in the middle of a block of code and want to see everything enclosed within the pair of braces that you’re in, you can click the Balance Braces button to select all text within your current set of braces.Line Numbers—. Toggles line numbers on and off within the editor.

Highlight Invalid Code—. Toggles highlighting of bad code on and off. While useful, invalid code highlighting can be troublesome when you’re making edits and temporarily have code that registers as invalid.

Apply Comment—. Adds comment tags to a selected block of HTML code. Choose from HTML comments or comments specific to a programming language, such as ColdFusion Markup Language.

Remove Comment—. Removes the comment tags from the currently selected block of text.

Wrap Tag—. Wraps the currently selected block of text within a tag of your choosing.

Recent Snippets—. Access recently used snippets of code from your Snippets library.

Move or Convert CSS—. Moves a selected CSS block to an external stylesheet, or converts inline CSS into a block-style CSS rule.

Indent Code—. Indent a selected group of lines.

Outdent Code—. Outdent (the opposite of indenting) a selected group of lines.

Apply Source Formatting—. As much as we might like to think we write pretty code, few of us really do. The Apply Source Formatting feature automatically formats your code according to the hierarchy of HTML tags and rules of the programming language you’re using (if any).

One of the most useful features of the Code Editor is code completion. Code completion is one of those things that you won’t think you’ll need until you actually use it. The process is simple—just start typing a valid tag or function from a programming language, and a list of matching tags appears, as seen in Figure 10.12.

Use your cursor keys (or your mouse) to select the tag you want to enter, and then press Return. The tag is automatically completed for you.

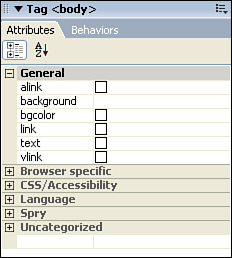

A tool that works hand-in-hand with the Code Editor is the Attributes panel, found in the Tag panel group. This panel is context sensitive. Wherever your cursor is located, the panel will display all of the available attributes for the tags that affect your current position.

For example, if you place your cursor in the <body> tag (or within content directly located within the <body></body> tags), the Attributes panel will look similar to what is shown in Figure 10.13.

Here, the general attributes for the <body> tag are shown and can be edited by clicking in the column to the right of their name. For example, to set the bgcolor (background color) for the body tag, you’d click the box to the right of bgcolor. This will open a small color chooser window where you can pick the color you want.

Besides just showing general attributes, the panel can also be used to control attributes that are specific to certain browsers, set attributes that control CSS styles and accessibility features, and so on. Just click the + button to the right of each attribute group to show the potential options for the tag you are editing.

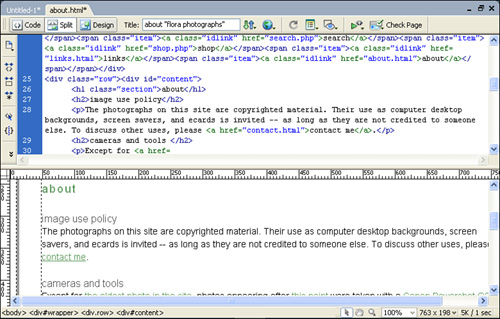

The second editing mode, Split view, gives you the ability to work directly with the code or with a visual representation of the page simultaneously. In this view, shown in Figure 10.14, the editing area is split into two parts. The upper half provides the same features as the Code Editor and can be used to directly enter and edit HTML or other programming information.

The lower portion of the view shows the live design layout. You can use Dreamweaver’s visual tools to create and edit content in this area. As you make changes in one area, they are immediately reflected in the other. This gives you an easy way to test out different styles and tags and see their effects without having to preview the page in your browser, or jump directly into a design-only view.

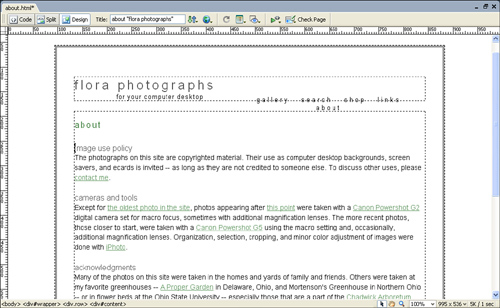

WYSIWYG web editors provide a visual process for designing pages rather than requiring the developer to write HTML syntax. The Design view is the purely visual mode that works like a page-layout program. You can drag images onto the page, type text, and use layout grids, tables, and layers to position elements just the way you like them, all without writing a line of HTML code. Figure 10.15 shows the Design view with rulers visible.

By default, the Design view has two view options active—rulers and guides. If you’ve used the other CS3 programs, you’re probably already familiar with what these are. The rulers provide a measurement in pixels, inches, or centimeters across and down the editor. The guides are horizontal or vertical markers that you can set up to help place content precisely within the design area.

To add a guide, just click and drag from within a ruler. For example, to add a guide at 250 pixels from the left side of the page, you’d place your cursor in the ruler at the left side of the editor (anywhere in the ruler area will do), and then click and drag into the design area. As you drag, a vertical line is drawn that extends through the editor. Simply continue dragging until it reaches the 250 pixel point, and then let go. The guide is invisible in the actual HTML page, but can be used to precisely align elements that you’re adding to the design.

Another helpful alignment tool that you might want to activate is the grid. To do this, use the View Options button at the top of the Design area. This button can be used to toggle any of the view elements on or off, should you find them distracting.

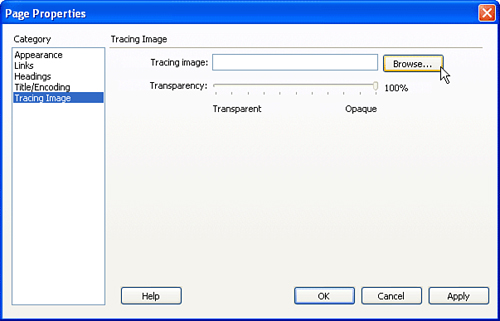

Another feature of the Design mode that can help you turn your web visions into reality is the tracing image. A tracing image is just what it sounds like—an image of what you want to create that can be placed in the design view for the purpose of tracing the layout into a working design.

To add a tracing image to the Design view, choose Modify, Page Properties. When the Page Properties dialog box appears, click Tracing Image. Your screen should now resemble Figure 10.16.

Click the Browse button to find and choose a graphics file to use as a tracing image, and then use the transparency slide to choose how opaque the image will appear in the design view. If you find the image too distracting or too faded, you can always re-open these settings and change the transparency at any time.

After the tracing image has been added, you can quickly turn it on and off using the View Options button, just as with the rulers, grid, and guides.

Although you can see the content, or body area, of your page design visually, there is a portion of your page that is important, yet hidden from view—the head.

The difference between these two areas is that the body portion is what loads into the browser window, whereas the head portion is used to give directions to the browser. The head section is where you put metatags, such as the keywords or description metatags that search engines use to index your site, links to external CSS and JavaScript pages, and more. A whole set of objects in the Common panel of the Insert group is devoted to the head portion of the page. You can select any head object to add it to the page, and then configure it using the Properties panel. But, if this is a purely visual design view, how do you see the head elements?

Once again, we turn to the View Options—this time, choosing Head Content. This makes a small bar visible across the top of the design area. Within the bar are icons representing different pieces of head content, such as the page title and content type. When one of these elements is selected, its properties are visible and editable within the Properties panel. Figure 10.17 shows the head content area visible with the Page Title icon selected.

This gives you complete access to the hidden portion of your web design without needing to access the source code!

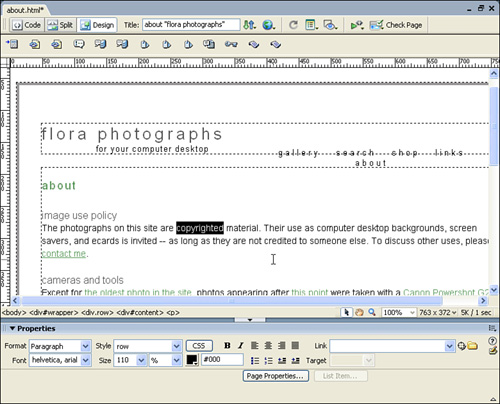

Now that the page is created and you’ve seen your view options, let’s take a look at adding and editing some actual page content. We’re going to be working in the Design view, because the ability to work visually makes web design a much more fluid process.

The first thing to try is just adding some text into the design area. Click inside the editor and start typing. As you’d expect, the text you enter appears onscreen—this is exactly what your visitors are going to see in your browser. Because you’re presumably already familiar with using a text editor, we’ll skip the details on how to move the cursor around and copy and paste—this should all work just as you’d expect.

What you probably want to do, however, is start styling the text content that you enter. To do this, look no further than the Properties panel, shown in Figure 10.18.

The controls visible when entering text should seem familiar—fonts, text sizes, alignment, ordered and unordered list formats, indenting, outdenting, and colors. Almost all the tools you’d expect in a common word processor are available for your use.

To set the style for a specific piece of text, just select the text in the Design view, and then click to apply the styles. If no selection is made when you apply a style, whatever styles you choose will be used when you enter more content.

Let’s take a closer look at two of the Properties panel tools that might require a bit more explanation: Colors and Links.

If you’ve opened the color chooser in Dreamweaver (usually represented by a small square with a triangle in the lower-right corner), you’ll notice that it is very different from choosing a color in an application like Photoshop.

Initially, a web-safe color palette is displayed that enables you to pick a color from the 212 web-safe colors available. For more variety, however, you can choose alternative color options by clicking the pop-up menu arrow in the upper-right corner of the color palette when it is being displayed.

Two other options can also make life easier if you find yourself feeling too constrained by the web color palette: the eyedropper and the system color pickers.

To use the eyedropper, just click the color square—your cursor changes to an eyedropper. Wherever you move and click the eyedropper, that color will be selected. This enables you to choose a color from anywhere on the screen, including your desktop background. If, at any time, you want to return to the default color setting, click the default color icon (a square with a line through it) in the upper-right corner of the Color panel.

A more precise way of choosing colors is by using the system’s Color Pickers. Once again, open the web-safe palette and click the right-most icon in upper-right corner. This will bring up the Color Picker that is native to your system.

A link is a hot spot—usually a few underlined words—that, when clicked, takes viewers to a new page, or to a specific location on a long scrolling page.

Because there are a number of ways to create these links, let’s review a few that you might find useful.

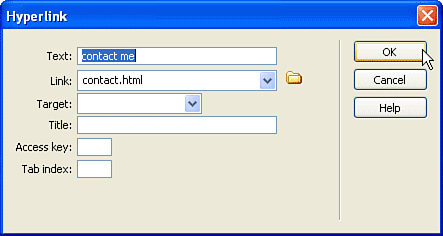

The first method of adding a link is to position your cursor where it should appear, and then click the Hyperlink object in the Insert panel. You should see a dialog box similar to that shown in Figure 10.19.

Use the Text field to set the text of the link that is displayed onscreen in the browser. Next, in the Link field, type the filename that should be displayed when the link is clicked. Alternatively, click the folder icon at the end of the field and choose a file directly from your site directory.

Leave the Target field empty, unless you want to open the link in a new window or a frame (which we’ll look at later in “Advanced Layout with Frames”). The remaining settings, as follows, are useful and can be defined however you’d like:

Title—. Link titles do not show up in the page itself, but appear as tooltips in many browsers.

Access Key—. This is a keyboard shortcut that can be used to access the link directly.

Tab Index—. Setting a tab index chooses the order in which the link will be highlighted when users press Tab to navigate the page.

When you’ve finished filling in the dialog box, click OK to create the link and add it to the web page.

Perhaps it’s just me, but this seems like an incredible hassle, just to add a link or two to a page. Luckily, as we hinted at earlier, Dreamweaver provides a myriad of other ways to link documents together...some of which are much faster.

The second way to create a link is by entering your link text directly into the Design view. After you’ve typed out what you want to be clickable, select the text with your cursor.

Next, using the Link field in the Properties panel, enter in the filename to link to and press Enter. Congratulations, you’ve just created another link!

For the third linking method, we’ll try something a bit more exciting. Again, enter and select a few words in the Design view. This time, however, instead of manually entering the file to link to, open and position your Files panel so that you can see the file you want to use with the link. Now look at the Properties panel. Just to the right of the Link field you should see a little crosshairs icon.

This is the Point-to-File icon, used to target a particular file. Click and hold on the crosshairs icon and drag to the file you want to link. As you drag, an arrow will be drawn from the crosshairs to the file in the Site window, as demonstrated in Figure 10.20. That’s it; you’ve just created a link by pointing to a file! Pretty nifty, huh?

There are actually even more ways to make links with Dreamweaver CS3. Using the Insert menu, or selecting the link-to-be-text and using the contextual menus, will also suffice. You can go back at any time and edit existing links through the Modify menu’s Change Link option, or, of course, by editing the Link field in the Properties window.

Now that you understand the basics of working with text content and the Properties panel, let’s take a look at another type of content you’ll want to add—images. Most websites, for better or worse, are graphics intensive, making use of images to convey information visually and to create compelling user interfaces.

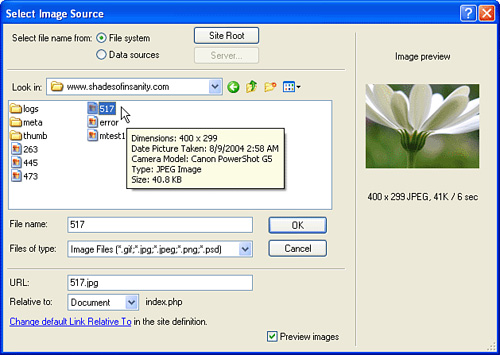

To insert an image, make sure your cursor is located where you want the image to appear, and then click the Image button in the Common panel of the Insert panel group, or choose Image from the Insert menu. Next, select the image from your site directory, as shown in Figure 10.21.

You’ll see a few options related to dynamic data when selecting the image from your drive. You can ignore these as they pertain to dynamic programming, which we won’t be getting into. One option you will want to take a look at is the Relative To: setting. This pop-up menu determines how Dreamweaver writes the links to the image. Usually you want to use the Relative to Document setting. This means that the links are created relative to one another. If an image is located two directories above the current document, the link in the document is set to look for an image two directories above it, no matter where you happen to store the file. Linking that is relative to the site root references the files based on the top of the website—moving the linked files anywhere else within the site breaks the link.

If you choose an image outside of your folder, Dreamweaver gives you the option of copying it into your site. You can also specify a URL to an image that is located remotely. Unfortunately, Dreamweaver only displays local images, so the design view might become a bit confusing if you link all your images into the site via remote URLs.

If you want to insert an image, but you don’t have one ready yet (waiting on the graphic designers again, huh?), you can insert a placeholder using the Image Placeholder object rather than an image. You can drag the handles (black squares) around the placeholder to size it in your document view. Later, you can assign an image file to the placeholder by selecting it and providing an image filename or URL in the Properties panel.

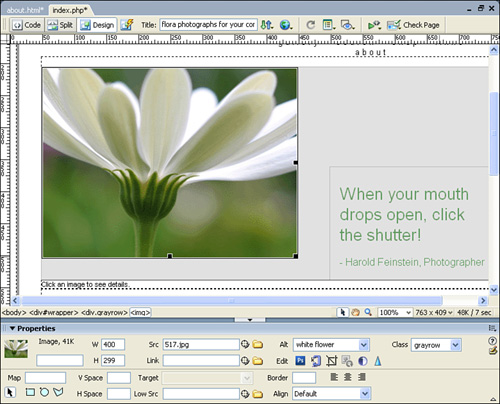

As with any HTML object that is inserted into a page, you can set certain attributes for an image. This is done by selecting the image in the Design view and then turning to our trusted friend, the Properties panel. As with the text content, there are a number of attributes that can be controlled for images. Figure 10.22 shows the image properties available in Dreamweaver CS3.

From left to right, these are the properties that can be set for images on your page:

Name—. Directly below the image size is a name that can be used to refer to it programmatically. This is typically used in JavaScript.

Width/Height—. The W and H fields set the width and height of the image as it will appear on the page.

Src—. The URL to the image that will be displayed.

Link—. If an image is to be used as a link, you can quickly add all the appropriate <a href> tags around it by just typing in the destination URL in this field.

Alt—. Alternative text to be displayed in case the image can’t be displayed or to be read aloud by browsers for the visually impaired. You should try to use alt attributes whenever possible.

Class—. The name of a style sheet class that should be applied, if any style sheets are defined.

V Space/H Space—. Set vertical and horizontal padding around the image.

Target—. The target window or frame to be set as the target if the image is being used as a link. This should usually be left blank.

Low Src—. Rarely used, this sets a URL to a low resolution (usually black and white) version of the image. This allows a version of the image to be displayed quickly, while the high-resolution version loads.

Border—. Sets a border around the image.

Justification—. The three justification alignment buttons in the lower-right of the Properties panel control where the image is placed in relation to the HTML text around it.

Align—. Determines where an image will lie in relation to objects that are next to it.

Using the Alignment properties to position text and graphics is beneficial when creating web pages that must be accessible to a variety of computers and browsers. If you are positioning text exactly (with tables or layers—something you’ll learn about later in “Advanced Layout with Tables”), you inevitably create pages that display poorly on low resolution screens or on displays that have different font settings. Using Alignment properties allows the images and text themselves to drive the display of the page. If text is too long, it will wrap around the image and fill the screen (or the parent object) as much as necessary.

If you don’t have complex image alignment requirements, allow the text to wrap around images on your pages. Any time you can design a page to take advantage of the cross-platform and cross-browser nature of HTML, it’s a good thing.

Linked images are common on the Web. When the user clicks a linked image, the browser loads the linked web page. With an image selected, you can add a hyperlink in a couple ways:

Type a URL into the Link box in the Properties panel.

Browse for the linked page by selecting the Browse icon beside the Link box.

Use the Point-to-File icon to link to a file. The Point-to-File icon enables you to simply drag the file over to the Files panel to create a link.

To enter a known URL as an image link, select an image on your web page and make sure the Properties panel is open. Enter a URL in the Link box underneath the Src box.

Notice that when you enter a URL in the Link box, the Border property automatically changes to 0. This is so that you do not have the hyperlink highlight as a border around the image. If you prefer to have a highlighted border, set the border to a value greater than 0. You can also set a border for an image that isn’t linked to anything. The border will then appear as a black box around the image.

After you save the web page, preview it in a browser. When you click the image that has the hyperlink, your browser should go to the hyperlinked page.

The Align pop-up menu in the Properties panel controls how objects that are located beside an image align with it. Align is very different from the text alignment settings you used previously. You use the text alignment settings to align an image in the center, to the left, or to the right of the screen. You use the Align pop-up menu to affect how other objects align with an image. In Figure 10.23, for instance, the image is aligned to the right of the text because Right is selected in the Align pop-up menu.

Change the Align setting of the image so that all the text appears to the left, beside the image. To do this, select Right from the Align pop-up menu in the Properties Panel. Why select Right? The image will be on the right. Remember that the Align options apply to the image but affect other elements within its vicinity. The alignment choices are described in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1. Image Alignment Options in the Properties Panel

Description | |

|---|---|

Default | Baseline-aligns the image, but this depends on the browser. |

Baseline | Aligns the bottom of the image with the bottom of the element. |

Top | Aligns the image with the highest element. Additional lines of text wrap beneath the image. |

Middle | Aligns the baseline of the text with the middle of the image. Additional lines of text wrap beneath the image. |

Bottom | Aligns the baseline of the text at the bottom of the image. |

TextTop | Aligns the image with the highest text (not the highest element, as with the Top option). Additional lines of text wrap beneath the image. |

Absolute Middle | Aligns the middle of the image with the middle of the text beside it. |

Absolute Bottom | Aligns the bottom of the highest element with the bottom of the image. |

Left | Aligns the image to the left of other elements. |

Right | Aligns the image to the right of other elements. |

To increase the distance between the image and other page elements, set the V Space and H Space. V stands for vertical and H stands for horizontal. To add space to the right and left of an image, put a value in the H Space text box. Horizontal space is added to both the right and the left of the image. Vertical space is added to both the top and the bottom of the image.

With Dreamweaver CS3, you can easily edit images that you’ve placed in your documents. Within the Edit section of the Properties panel, you’ll see six buttons that can be used to edit your images directly (sort of) in Dreamweaver. Changes you make with these tools are permanent, so be careful what you do!

These controls are

Edit—. Opens the selected image in Photoshop for editing (or in another application set in the File Types/Editors section of the Dreamweaver CS3 preferences).

Optimize—. Opens the selected image in the Dreamweaver optimization window.

Crop—. Lets you trim off unwanted portions of the image and saves the smaller file. This command works within Dreamweaver, enabling you to save the cropped image.

Resample—. This command becomes active after you’ve resized an image in Dreamweaver. It optimizes an image by adding or removing pixels in the image. This command works within Dreamweaver.

Brightness and Contrast—. Changes the brightness and contrast of an image to correct an image that is too bright or too dark. This command works within Dreamweaver.

Sharpen—. Sharpens a blurry image. This command works within Dreamweaver.

You can access all these image-editing commands from the Properties panel when you have an image selected. Make sure you have a backup copy of any images you modify because Dreamweaver changes the actual image file.

Although they aren’t as full featured as Illustrator or Photoshop, these controls enable you to perform common image-editing tasks without leaving the comfort of the web design app.

Dreamweaver CS3 makes it easy to implement rollover images by using the Rollover Image object. A rollover is an image that swaps to another image when the viewer’s cursor is over it. You need two image files with exactly the same dimensions to create a rollover.

To create a rollover image, follow these steps:

Place the insertion point where you want the rollover image to appear.

Select the Rollover Image object from the Common panel of the Insert panel group or select Insert, Image Objects, Rollover Image. The Insert Rollover Image dialog box appears.

Type a name for the image in the Image Name text field.

Select both the original image file and the rollover image file by clicking the Browse buttons next to those options and selecting the image files.

Check the Preload Rollover Image check box if you’d like the rollover image downloaded into the viewer’s browser cache when the page first loads. With a preloaded image, there is less chance that the viewer will have to wait for the rollover image to download when she moves the cursor over the image.

Add Alternate text that describes the image. This helps the visually-impaired to browse and understand your site.

Add a link to the rollover image by clicking the Browse button next to When Clicked, Go to URL or type in the external URL or named anchor.

The Insert Rollover Image dialog box should look as shown in Figure 10.24. Click the OK button.

What if you wanted to create a bunch of rollover images as a navigation bar? And what if you wanted each of them to have a down button state, too? You could create all these buttons individually, or you could use the Dreamweaver Insert Navigation Bar dialog box to create all the buttons at once.

You simulate a button by swapping images that are the same size but look slightly different. Each image represents a button state. The default button state is up. The down state appears when the user clicks the mouse on the button; the down state image usually modifies the up state image so that it looks pressed down. The over state appears when the user passes his mouse over the button. The navigation bar can also add an over when down state, which appears when the user rolls the mouse over the button when it is already in the down state. You must add an up state image to a navigation bar, but all the other button states are optional.

To create a navigation bar, follow these steps:

Select the Navigation Bar object from the Common panel or select Insert, Image Objects, Navigation Bar. The Insert Navigation Bar dialog box appears.

An initial, unnamed button element is visible. Change the element name to the name of your first button. (If you simply go to the next step, Dreamweaver will automatically give your button the same name as the name of the image file.)

Browse to load a button up image, a button over image, and a button down image. You can also enter an over while down image. All these images must be the same size.

Enter a hyperlink in the When Clicked, Go to URL box. Type in a URL or browse to a web page. The Target pop-up menu next to the URL box enables you to target a specific frame. You’ll explore frames later in “Advanced Layout with Frames.”

Check the Preload Images check box if you want the images to be automatically preloaded when the page first loads. Check the Show Down Image Initially check box if you want the button to appear pressed in at first.

Add additional buttons by clicking the plus button at the top of the dialog box and repeating steps 2–5. Rearrange the order of the buttons by using the arrow buttons at the top of the Insert Navigation Bar dialog box. To delete a button, click the minus button.

At the bottom of the Insert Navigation Bar dialog box, choose to insert the navigation bar either horizontally or vertically into the web page. Select the Use Tables check box if you’d like the navigation bar to be created in a table. (The section “Advanced Page Layout by Using Tables” explains how to use tables for layout.) The table layout occurs here for you automatically.

When you are finished adding buttons, click OK.

To test the buttons, save your file and preview it in a browser. If you’ve made a mistake, don’t fret! You can edit the navigation bar by selecting the Navigation Bar object again.

An image map is an image that has regions, called hotspots, defined as hyperlinks. When a viewer clicks a hotspot, it acts just like any other hyperlink. Instead of adding one hyperlink to an entire image, you can define a number of hotspots on different portions of an image. You can even create hotspots in different shapes.

Image maps are useful for presenting graphical menus that the viewer can click to select regions of a single image. For instance, you could create an image out of a picture of North America. You could draw hotspots around the different countries in North America. When the viewer clicked a country’s hotspot, she could jump to a web page with information on that country.

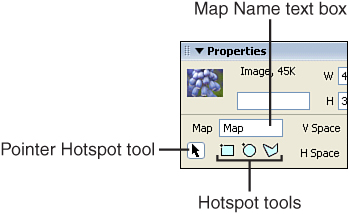

When an image is selected, you see four image map tools in the lower corner of the expanded Properties panel. These four tools are used to define image map hotspots. The arrow is the Pointer Hotspot tool, which is used to select or move the hotspots. There are three image map hotspot tools: One tool draws rectangles, one draws ovals, and one draws polygons.

To create an image map, follow these steps:

Insert an image into a web page. The image must be selected for the image map tools to appear in the Properties panel.

Give the map a name in the Map Name text box, as shown in Figure 10.25. The name needs to be unique from other map names in the page.

Select one of the hotspot tools. You’ll spend the next minutes exploring each of the hotspot tools in depth.

With a newly drawn hotspot selected, type a URL in the Link box, or click the Browse icon to browse to a local web page. You can also link a hotspot to a named anchor by entering a pound sign followed by the anchor name.

Enter alternative text for the hotspot in the Alt text box; some browsers display this text as a tooltip.

Optionally, select a window target from the Target pop-up menu in the Properties panel. Setting a target window will open a new browser window when the link is clicked. Most of the time, you probably won’t select a target.

You set all the image properties for an image map just as you would an ordinary image. You can set the vertical space, horizontal space, alt text, border, and alignment. If you copy and paste the image map into another web page, all the image map properties come along, too.

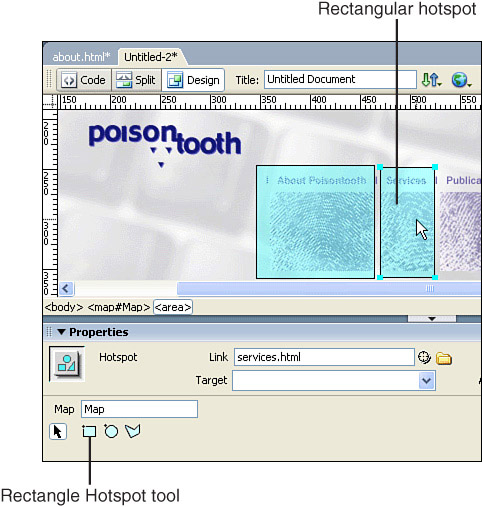

To add a rectangular hotspot to your image map, first select the Rectangle Hotspot tool. Click and drag the crosshair cursor to make a rectangle the dimensions of the hotspot you want to create. When you release the mouse, a highlighted box appears over the image, as in Figure 10.26. With the hotspot selected, enter a URL into the Link box in the Properties panel.

To move or adjust the size of the hotspot, you need to first select the Pointer Hotspot tool. You can’t use the other hotspot tools to adjust the hotspot, or you will end up creating another hotspot. Click the hotspot with the Pointer Hotspot tool and either move the hotspot to another location or resize the hotspot by using the resizing handles.

In the web page HTML, the rectangular hotspot is defined by two sets of x and y coordinates. The upper-left corner of the rectangle is recorded as the first two coordinates in the code and the lower-right corner of the rectangle is recorded as the last two coordinates. The coordinates are in pixels, and they are relative to the image, not to the web page.

A circular area might better define some areas in your image map than a rectangular one. You create a circular hotspot just as you create a rectangular one. Select the Oval Hotspot tool and then click and drag to create the hotspot—press Shift as you draw to make the hotspot a perfect circle. Reposition or resize the hotspot by using the Pointer Hotspot tool.

You can understand why you can have only a circle and not an ellipse when you see how the circular hotspot coordinates are defined. A circle is defined by three values: The circle’s radius and the x and y values that define the circle’s center.

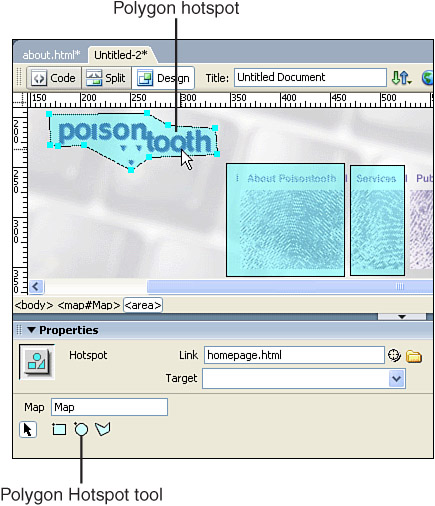

Sometimes the area you’d like to turn into a hotspot just isn’t circular or rectangular. The Polygon Hotspot tool enables you to create any shape you want to define as an irregular hotspot.

You use the Polygon Hotspot tool a little differently than you use the Oval or Rectangle Hotspot tools. First, select the Polygon Hotspot tool from the Properties panel. Instead of clicking and dragging to create a shape, click once for every point in the polygon, as shown in Figure 10.27. You should move around the area you want to define as a hotspot in either a clockwise or counterclockwise manner; clicking randomly may create an odd polygon. When you are finished creating the points of the polygon, select the Pointer Hotspot tool to complete the polygon. You select the Pointer Hotspot tool to deselect the Polygon Hotspot tool so you don’t accidentally add stray points on the screen. Or you can double-click when you are finished drawing the polygon.

A polygon is defined by as many x and y coordinates, each representing one of the corner points, as you need to define the hotspot shape.

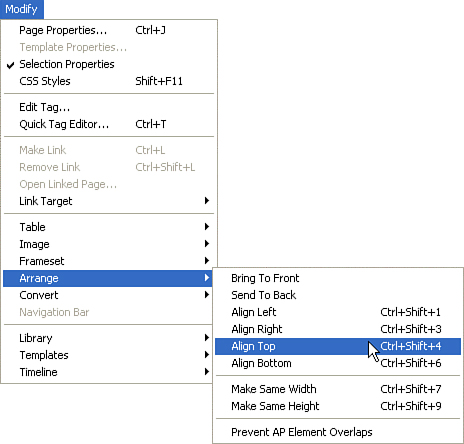

Dreamweaver has built-in alignment tools that you can use to align the hotspots in an image map. First, you need to select the hotspots you want to align. To select all the hotspots in an image map, use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+A in Windows or Command+A on the Macintosh. Or you can hold down Shift as you click hotspots to add them to the selection. You can tell when hotspots are selected because you can see the resizing handles.

Sometimes it is difficult to finely align hotspots with your mouse. You can use the arrow keys to move a hotspot or multiple hotspots one pixel at a time. The Arrange submenu under the Modify menu contains commands to align hotspots, as shown in Figure 10.28. You can align multiple hotspots on the left, right, top, or bottom. You can make multiple hotspots the same height by using the Make Same Height command or the same width by using the Make Same Width command.

Hotspots can overlap each other. Whichever hotspot is on top (usually the one created first) will be the link triggered by clicking on the overlapping area. You can change the stacking order of hotspots by using the commands located in the Arrange submenu of the Modify menu. You might want to create overlapping hotspots on purpose as part of the design of an image map. For instance, you might use a circular hotspot over part of a rectangular hotspot. Alternatively, the overlapping might simply be a consequence of the limited shapes you have available to define the hotspots.

It’s difficult to tell which hotspot is on top of another hotspot. If you’ve recently created the image map, you know which hotspot was created first and is therefore on top. You can manipulate the stacking order of the hotspots by selecting Modify, Arrange, Bring to Front or Send to Back. If a hotspot overlaps another and needs to be on top, select the Bring to Front command.

Using the tools you’ve seen to this point, you can create web pages with styled text and images. Although these pieces make up most of the sites you’ll create (or visit!) you don’t have the tools you’ll need to create compelling layouts. There are three approaches we’ll look at for laying out information on the screen—tables, frames, and CSS layers.

Tables give web developers the ability to make page elements appear in a specific place onscreen. Dreamweaver enables you to work in Layout view so you can draw table elements directly onto the Document window. This makes it easy to create tables for page layout. Let’s start, however, with just adding a table and using it as you would in something like Microsoft Word.

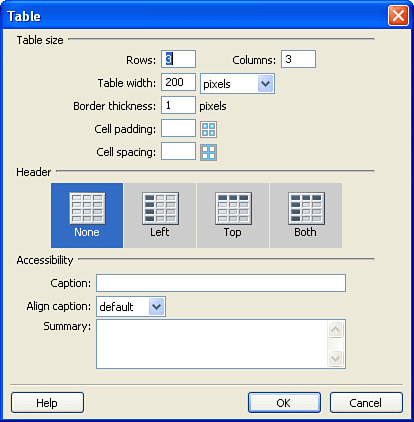

To insert a table into your web page, follow these steps:

Place the insertion point in your web page where you want the table to be inserted.

Select the Table button in the Common panel (Insert panel group) or choose Insert, Table. The Table dialog box appears, as shown in Figure 10.29.

Accept the default values or enter your own values into the Rows and Columns text boxes. By default, Dreamweaver creates a 3 by 3 table.

If you’d like a border to be drawn around the table, choose the number of pixels wide the border should be. For no border, enter 0.

Set the amount of space between the content contained in a cell and the border of the cell—the cell padding.

Use Cell Spacing to set the amount of space, horizontal and vertical, between two cells.

If you’d like to have headings for the columns or rows in your table, make the appropriate choice in the Header section of the Table dialog. The contents of header cells appear bold and centered by default.

Finally, configure your accessibility options. You can add a caption for a table that appears in the browser and is visible to everyone. You can set the alignment for the caption so that it appears above, below, to the left, or to the right of the table. You should always add a summary for your table. The summary is read by screen readers and helps the visually impaired user evaluate whether to progress through the table data or skip the information.

When you’re done setting values in this dialog box, click OK.

A table with the attributes you’ve specified is inserted into the document.

When you have your table structure determined, you can start adding text or images to the table. You can also fine-tune the structure as you work in Dreamweaver by using the Properties panel and selecting table cells or entire tables.

To enter content, click in a table cell, type, and then tab to the next cell. You can press Shift+Tab to move backward through the table cells. When you reach the rightmost cell in the bottom row, pressing Tab creates a new row.

To remove a row or column from a table, use the context menu that pops up when you right-click (Control+click on the Mac) a table cell. Right-click (Control+click on the Mac) a table cell and select Table; a submenu appears, with a number of commands to add and remove rows, columns, or both. Select one of these commands to make a change to the table.

Use the icons in the Layout panel of the Insert panel group to add rows either above or below the current row or to add columns to the left or the right of the current column. You can also add or remove rows and columns by editing the table properties in the Properties panel. Adjust the number of rows and columns in the Properties panel with an entire table selected to add or remove groups of cells.

You can change column width and row height by dragging the cell borders or by entering values in the Properties panel. If you prefer to “eyeball” the size, position the cursor over a cell border until the cursor turns into the double-line cursor. Drag the double-line cursor to change the column width or row height.

Use the W (width) and H (height) boxes in the Properties panel to give exact values to widths and heights. Values are expressed in either pixel or percentage values. A percentage value changes your table size as the size of the browser window changes, whereas a pixel value always displays the table at a constant size.

Just as you can change the size of cells, rows, and columns, you can change the size of an entire table. With the entire table selected, drag the resizing handles to make the table a different size. If you have not given width and height values to cells, rows, and columns, the cells distribute themselves proportionally when the entire table size is changed. Or use the W and H boxes in the Properties panel, with the entire table selected, to give the table either pixel or percentage size values.

When your table is selected, you’ll notice a gray bar appear below it. Within this bar are pop-up menus below each column, and a central pop-up menu in the middle. You can use these menus to quickly clear the width of a column, or of the entire table.

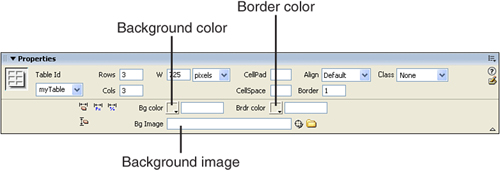

You can also clear the cell heights and clear the cell and convert all the values between pixels and percentages in the Properties panel, as seen in Figure 10.30.

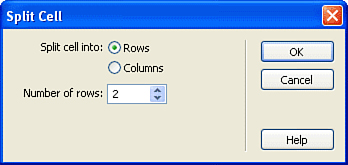

You might want some rows or columns in your table to have fewer cells than other rows. For example, you might want the top row of a table to have a title that is centered over all the columns. How do you accomplish that?

You can increase or decrease the column span and row span by either splitting or merging cells. To merge an entire row so it appears as one cell, select the row and click the Merge button in the Properties panel or right-click anywhere on the row and select the Merge Cells command from the Table submenu of the context menu. Now the content of the entire row can be positioned over all the columns.

Use the Split Cell command to add additional rows or columns to a cell. The Split button is beside the Merge button in the Properties panel. Select the Split button or right-click (or Control+click) in the cell and select the Split Cell command from the Table submenu of the context menu, and the Split Cell dialog box appears, as shown in Figure 10.31. Enter the number of rows or columns you would like the cell to be split into and click OK. Now a single cell is split into multiple cells.

You can align the contents of a cell or a group of cells vertically—from top to bottom. The Vert pop-up menu in the Properties panel sets the vertical alignment for the contents of an individual cell or a group of cells.

Align the contents of a cell or a group of cells horizontally—from left to right—with the Horz pop-up menu.

There are several places you can add color to a table:

A background color for a table cell or group of cells

A background color for the entire table

A border color for a table cell or group of cells

A border color for the entire table

Figure 10.32 shows the different table colors in the Properties panel. Cell properties always have priority over the same properties in the table. For instance, if you applied blue as the table background color and then applied red to an individual cell, the one cell would be red and all the other cells would be blue. Set the table background and table border in the Properties panel. The Brdr Color setting determines the border color of the entire table.

You can add a background image to a table cell or an entire table. Enter the URL for a background image in the box labeled Bg Image in the Properties panel. You can enter a pixel value in the Border text box to see a border; however, you don’t usually add borders to a layout table. If you add a border color and don’t see the border, you might have the border size set to zero. Set the cell background and cell border colors in the Properties panel with a cell or group of cells selected.

Traditionally, designing tables for page layout has been a complicated task. Making changes or creating the perfect number of cells has required web developers to combine various rows and columns to get pages to look the way they want them to. Dreamweaver includes Layout view, which enables you to easily draw, move, and edit table cells.

To turn on Layout view, select View, Table Mode, Layout Mode. When you turn on Layout view, two layout buttons on the Layout panel (Insert panel group) become active. One of these buttons, Draw Layout Table, draws a layout table; the other, Draw Layout Cell, draws an individual layout cell (a table cell). A layout table looks just like a regular HTML table in the web browser, but it looks slightly different in Dreamweaver. In Dreamweaver, you can manipulate layout tables and layout table cells by clicking and dragging them into position on the page.

Dreamweaver’s Layout view enables you to draw onto the Document window a design that will appear in table cells. You create areas for content, menus, and other elements of a web page by selecting the Draw Layout Cell command and drawing cells for each page element.

To create a layout, follow these steps:

Select the Layout Mode from the Table Mode options in the View menu.

Select the Draw Layout Cell button in the Layout panel of the Insert panel group.

Draw cells in the Document window for page elements, as shown in Figure 10.33. A layout table is automatically created to hold the layout cells.

Alternatively, you can draw the layout table first, and then draw cells within it.

After your design is onscreen, you can click the borders of the layout cells and use the handles to resize the layout.

To quickly select a cell to edit its properties, hold down Ctrl and click (Command+click on the Mac) within the cell. As shown in Figure 10.34, the Properties panel presents the Width, Height, Bg (background color), Horz (horizontal alignment), Vert (vertical alignment), and No Wrap properties. These properties are exactly the same table cell properties that you learned about earlier. There’s one additional property, Autostretch, which is unique to layout tables.

Autostretch enables a column to stretch to fill all the available space in the browser window. No matter what size the browser window is, the table will span the entire window. When you turn on Autostretch for a specific cell, all the cells in that column will be stretched. This setting is particularly useful for cells that contain the main content of the page. The menus can stay the same width, but the content can stretch to take up all the available space. Or you can place a stretched cell on the right side of a table and stretch the background colors over the width of the screen, no matter what the user’s resolution.

Dreamweaver automatically adds spacer images to table cells to make sure they remain the size that you intend in all browsers. The spacer image trick is an old trick used by web developers to ensure that table cells don’t collapse when viewed in certain browsers. A transparent one-pixel GIF is stretched to a specific width. This image is not visible in the browser. The GIF maintains the width of all the cells that are not in the autostretched column. If you do not add a spacer image, any columns without an image to hold their size might collapse.

To turn on Autostretch, follow these steps:

Select a cell by holding Ctrl while clicking the cell.

Select the Autostretch radio button in the Properties Panel. The Choose Spacer Image dialog box appears.

In the Choose Spacer Image dialog box, you have three choices:

Create a Spacer Image File—When you select this option, Dreamweaver creates an invisible one-pixel GIF image, adds it to the top cell of each column, and stretches it to the column width. Dreamweaver asks you where you’d like to store the

spacer.gifimage that Dreamweaver creates.Use an Existing Spacer Image File—If you’ve already created a spacer image, select this option. Dreamweaver asks you to navigate to where the image is stored.

Don’t Use Spacer Images for Autostretch Tables—If you select this option, Dreamweaver warns you that your cells may collapse and not maintain the widths you have set.

Love ‘em or hate ‘em, many people seem to have strong opinions about frames. Creating a web page with frames enables you to contain multiple web pages in a single browser window. The user can select a link in one frame that loads content into another existing frame, enabling the user to stay in the same browser window.