Illustrator is a program that seems to have an identity crisis. By that, I mean it’s a tool that can do many of the things that InDesign can (such as page layout), and it can also do many of the things that Photoshop can (such as web design). Of course, there are also plenty of things that Illustrator alone can do (such as edit PDF files or create 3D graphics). As you’ll see in this chapter, one thing is certain: Illustrator is a very deep program, with a wide range of features and uses.

When you first launch Illustrator, you’re greeted with the Illustrator CS3 welcome screen (see Figure 7.1). The welcome screen is split into four sections. The top two areas offer quick links to open recent files and access common functions, such as creating a new file. The bottom portion of the window provides links to How-to documents and online resources. If you’d prefer to avoid this screen altogether, you can do so by clicking the “Don’t Show Again” check box.

Taking a look at the screen when you first start Illustrator (see Figure 7.2), you have the standard menu bar across the top of the screen and, directly beneath it, Illustrator’s context-sensitive Control panel. Along the left side of the screen is the toolbox, which contains all of Illustrator’s tools, as well as several other functions. The color proxy indicates the fill and stroke colors (you can also choose colors by double-clicking on them); the two icons above the proxy enable you to set the colors to the default white fill and black stroke, and to swap the fill and stroke colors. Directly below the proxy icons are three buttons that can be used to quickly apply three kinds of colors: a white fill, a black-to-white gradient, and none. Under those are the different view modes, Standard, Full Screen with Menu Bar, and Full Screen (just as in Photoshop). You can toggle through the view modes by repeatedly pressing the F key on your keyboard (the letter F, not the Function key).

Along the right side of your screen are some of Illustrator’s panels. We discuss what each of them does and how to use them as we go through this chapter.

Finally, the document window is where you work on your file. The black outline is your document size, or artboard. Illustrator lists the filename, the view percentage, and the color mode right in the title bar of each file. Along the bottom left of the window, you’ll find a zoom indicator as well as the status bar.

Illustrator’s Control panel has several cool features built into it that make it extremely powerful and easy to use (see Figure 7.3). On the left of the Control panel, Illustrator indicates the targeted selection (in this case, a path). You’ll also notice that some of the words in the panel are underlined and are colored blue, just like links in a web browser. When you click on these words, Illustrator opens the panel for that feature, giving you access to all of the necessary functions. For example, you can easily specify the width for a stroke in the Control panel, but you can also click on the word Stroke to open the Stroke panel and specify additional settings. At the far right of the Control panel is the Go to Bridge button and a flyout menu that enables to you show or hide different functions in the Control panel itself.

In a program such as Photoshop, you usually start with a scanned image or a digital photograph. With Illustrator, though, you’ll most likely be creating new documents more often, as well as creating new documents based on predefined templates. Of course, Illustrator can also open existing documents.

To start from scratch and create a new file, choose File, New, or press (Cmd-N) [Ctrl+N] to access the New Document dialog box (see Figure 7.4). Here you can give your file a name (you can do this later when you actually save the file, too), choose a profile for your document, and specify your artboard size and orientation. You can choose from any of Illustrator’s supported measurement systems: points, picas, inches, millimeters, centimeters, or pixels. Using the Templates button, you can jump to a directory containing dozens of templates ranging from event planning to DVD labels to give you a jumpstart on your document design.

For even greater control, click the Advanced button to choose a preview mode, color mode, and the PPI in which raster effects will be rendered.

Illustrator lets you create files in one of two color modes, and it’s important to know which one to choose. Although you can change color modes later, such changes will cause color shifts. Each color mode has a gamut, or range of colors that can be produced. Some gamuts are wider, or can contain more colors, than others. For example, certain colors can be displayed in RGB that simply can’t be reproduced in CMYK (for example, bright greens, oranges, or pastel colors). So converting an RGB file to CMYK might cause some colors to become dull or change the colors altogether because those colors don’t exist in CMYK. Let’s take a look at each of the supported color models:

RGB Color—. RGB (red, green, blue) is a color method used to display color on televisions, computer monitors, and video screens. In RGB, you start with black (when your TV is off, the screen is black), and adding equal values of red, green, and blue results in white. When you’re working on files that will be used in video, for broadcast, on the Web, or for onscreen presentations, RGB is the format you should use.

CMYK Color—. CMYK is a color method used to print color on paper. Unlike RGB, in the CMYK color space, if you mix all the colors together, you get black, but if none of the colors is present, you get white. Anything you see in print uses CMYK (a blank piece of paper is white), so obviously, when you’re designing content that will be printed in color, CMYK is the color model of choice. CMYK stands for cyan (a shade of blue), magenta (a shade of red), yellow, and key (black).

After you’ve specified your new document settings, you can click the OK button to create a new Illustrator file.

An Illustrator template file is a special kind of Illustrator file, sporting an .ait file extension instead of the usual .ai reserved for Illustrator files. Templates are used for designs that are used repeatedly, and they can contain anything a normal Illustrator file can contain, including layers, paragraph styles, symbols, page size—even artwork itself. When you open an Illustrator template, the file opens a copy of the template as an untitled document (as if you had created a new file). This prevents you from accidentally overwriting the template file.

Illustrator ships with many professionally designed royalty-free templates you can use. When you choose File, New from Template, or click the Templates button in the New dialog, Illustrator automatically navigates to the folder where these templates are installed. Using the Adobe file dialog, you can choose Thumbnails from the View pop-up menu at the far right of the window. This automatically shows a preview of each template file as you browse, as seen in Figure 7.5. You can also use Bridge to browse through the templates if you prefer its interface.

For those who feel that using prerendered content is beneath them, Illustrator also ships with a full collection of blank templates. These can be quite useful for nearly any user.

As with just about any computer program, you can open a file by choosing File, Open or pressing (Cmd-O) [Ctrl+O] to open a file. By default, this invokes the Adobe File dialog box which features file content previews and direct access to Version Cue. If you’re more comfortable with your default operating system dialog, click the OS Dialog button. After you’ve located the file you want to open, click on the Open button to open the file. Keep in mind that you can always use Adobe Bridge to browse for the right file you need.

Illustrator does more than just open Illustrator files. You can open a wide range of files in Illustrator, including PDF, EPS, JPEG, PSD, GIF, PNG, and more. Illustrator can also open native CorelDRAW and FreeHand files (versions 8, 9, and 10 officially, although other versions might work with varying success). In many ways, both Photoshop and Illustrator can be used as utilities to open just about any kind of graphics file.

Back in Chapter 2, “So Many Applications: Which One to Use?” we discussed the underlying basics of vector graphics. Now you’ll learn how to draw them. We begin with drawing closed paths, and then we move on to drawing open paths. Finally, we discuss how to edit existing vector paths and objects.

Illustrator can draw primitive shapes quite easily, and several shape tools enable you to create rectangles, ellipses (circles and ovals), polygons (multisided shapes), and stars. We go through each of these tools and how they are used, but, of course, the best way to get to know them is to launch Illustrator and try them for yourself.

One thing you’ll notice, though, as you read through the remainder of this chapter, is that there are usually several ways to accomplish the same task. This is true for most of the functionality you’ll find in Illustrator and throughout the CS3 suite. As you become more familiar with Illustrator, you’ll get a better feel for which method makes the most sense for a specific purpose or is best suited to your personal workflow.

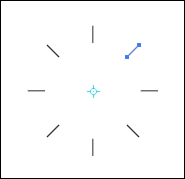

Finally, as you’ll see, most of Illustrator’s shape drawing tools, shown in Figure 7.7, are dynamic, in that you can press certain keys on your keyboard to change certain aspects of the shape as you are drawing it.

To draw a rectangle, choose the Rectangle tool and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the shape you are drawing:

Press the Shift key to constrain your shape to be a perfect square.

Press the (Option) [Alt] key to draw your shape from the center outward.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your shape and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your shape.

To draw a rectangle numerically, choose the Rectangle tool and click once on your artboard to get the Rectangle dialog box (see Figure 7.8). Enter a value for the width and height, and click OK. To draw a rectangle numerically from its center, press and hold the (Option) [Alt] key while you click once on the artboard.

To draw a rounded rectangle (in which the corners of the rectangle are rounded), choose the Rounded Rectangle tool and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the shape you are drawing:

Press the Shift key to constrain your shape to be a perfect square with rounded corners.

Press the (Option) [Alt] key to draw your shape from the center outward.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your shape and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your shape.

To draw a rounded rectangle numerically, choose the Rounded Rectangle tool and click once on your artboard to get the Rounded Rectangle dialog box (see Figure 7.9). Enter a value for the width, height, and corner radius, and click OK. To draw a rounded rectangle numerically from its center, press and hold the (Option) [Alt] key while you click once on the artboard.

To draw an ellipse (also called an oval), choose the Ellipse tool and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the shape you are drawing:

Press the Shift key to constrain your shape to be a perfect circle.

Press the (Option) [Alt] key to draw your shape from the center outward.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your shape and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your shape.

To draw an ellipse numerically, choose the Ellipse tool and click once on your artboard to get the Ellipse dialog box (see Figure 7.10). Enter a value for the width and height, and click OK. To draw an ellipse numerically from its center, press and hold the (Option) [Alt] key while you click once on the artboard.

The Polygon tool in Illustrator is a bit disconcerting. A real polygon is simply a closed shape with at least three sides. In Illustrator, the Polygon tool can create only closed shapes with three or more sides, but in which all the sides are equal in length.

To draw a polygon, choose the Polygon tool, and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. A polygon is always drawn outward from its center. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the shape you are drawing:

Move your mouse in a circular motion to rotate the shape.

Press the Shift key to constrain your shape straight to the baseline (or whatever your constrain angle is set to in General Preferences).

Press the up arrow key on your keyboard to add sides to your shape.

Press the down arrow key on your keyboard to remove sides from your shape.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your shape and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your shape.

To draw a polygon numerically, choose the Polygon tool and click once on your artboard to get the Polygon dialog box (see Figure 7.11). Enter a value for the radius and the number of sides, and click OK.

The Star tool in Illustrator can be quite useful for creating starbursts to call out specific items in a design.

To draw a star, choose the Star tool and click and drag the mouse on your artboard. A star is always drawn out from its center. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the shape you are drawing:

Move your mouse in a circular motion to rotate the shape.

Press the Shift key to constrain your shape straight to the baseline (or whatever your constrain angle is set to in General Preferences).

Press the up arrow key on your keyboard to add points to your shape.

Press the down arrow key on your keyboard to remove points from your shape.

Press the (Option) [Alt] key to align the shoulders of your star (forcing lines on opposite sides of the star to share the same baseline).

Press the (Cmd) [Ctrl] key to adjust the inner radius of the star. Dragging toward the center of the star decreases the radius, and dragging away from the center of the star increases it.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your shape and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your shape.

To draw a star numerically, choose the Star tool and click once on your artboard to get the Star dialog box (see Figure 7.12). Enter a value for Radius 1 and Radius 2, enter the number of points, and click OK.

Illustrator CS3 introduces the Flare tool. Unlike the other shapes we’ve looked at, flares are a bit more complex. The Flare tool is used to generate the lens flare effect—a series of concentric circles, rays, and staggered halos, similar to what you might see when light shines through a lens. To get the best effect from the Flare tool, you should use it on top of existing artwork, much as you’d see one in a photograph.

To draw a flare, choose the Flare tool, and then click and drag the mouse to set a size. The main flare shape will be drawn. Next, move the mouse and click and drag to set the secondary halos for the flare. You can use the mouse to adjust their location in relation to the primary shape. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the shape you are drawing:

Press the Shift key to constrain the angle of the rays in the flare straight to the baseline (or whatever your constrain angle is set to in General Preferences).

Press the up arrow key on your keyboard to add rays to your flare.

Press the down arrow key on your keyboard to remove rays from your flare.

Press the (Cmd) [Ctrl] key to keep the center of the flare from moving as you draw.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your shape.

To draw a flare numerically, choose the Flare tool and click once on your artboard to get the Flare Tool Options dialog box (see Figure 7.13). Enter values for the center, rings, halo, and rays, and click OK.

Although drawing complete shapes is something just about everyone needs to do inside of Illustrator, it’s equally important to create open-ended paths. Illustrator has several tools for creating these kinds of paths (seen in Figure 7.14) and, as you’ll see, different ways to edit them as well.

To draw a straight line, choose the Line Segment tool and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the path you are drawing:

Press the Shift key to constrain your path to increments of

.

.Press the spacebar to “freeze” your path and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your path.

To draw a line numerically, choose the Line tool and click once on your artboard to get the Line Segment Tool Options dialog box, shown in Figure 7.15. Enter a value for the length and the angle, and click OK.

To draw an arc, choose the Arc tool and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the path you are drawing:

Press the Shift key to constrain your path so that the length of the x- and y-axes are the same (thus creating a perfect quarter-circle).

Press the (Option) [Alt] key to draw your path from the center outward.

Press the up arrow key on your keyboard to make the slope of the path more convex.

Press the down arrow key on your keyboard to make the slope of the path more concave.

Press the C key to draw the arc as a closed-path shape.

Press the F key to flip the path along its axis.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your path and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your path.

To draw an arc numerically, choose the Arc tool and click once on your artboard to get the Arc Segment Tool Options dialog box (see Figure 7.16). Enter values for the length of the x-axis and the y-axis, and for the slope. Choose also to draw an open or closed path and an axis on which to base the path, and click OK.

Illustrator has a cool tool for drawing spirals, and the best part is that you don’t get dizzy drawing them!

To draw a spiral, choose the Spiral tool and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. A spiral is always drawn outward from its center. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the path you are drawing:

Move your mouse in a circular motion to rotate the path.

Press the Shift key to constrain the path to increments of

.

.Press the up arrow key on your keyboard to add segments (or winds) to your path.

Press the down arrow key on your keyboard to remove segments (or winds) from your path.

Press the (Option) [Alt] key to adjust the length of the path.

Press the (Cmd) [Ctrl] key to adjust the decay of the path. The decay setting controls how close the winds of the spiral are to each other.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your path and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your path.

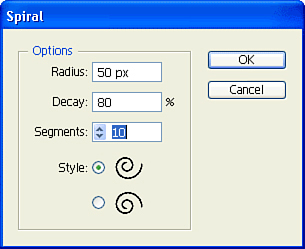

To draw a spiral numerically, choose the Spiral tool and click once on your artboard to get the Spiral dialog box (see Figure 7.17). Enter values for the radius, the decay, and the number of segments; then choose a style and click OK.

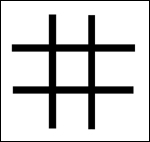

Although it’s not necessarily a path tool, the Rectangular Grid tool enables you to easily construct a grid using both paths and a single rectangle.

To draw a rectangular grid, choose the Rectangular Grid tool and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the grid you are drawing:

Press the Shift key to constrain your grid to a perfect square.

Press the (Option) [Alt] key to draw your grid out from its center.

Press the up arrow key on your keyboard to add rows to your grid.

Press the down arrow key on your keyboard to remove rows from your grid.

Press the right arrow key on your keyboard to add columns to your grid.

Press the left arrow key on your keyboard to remove columns from your grid.

Press the X and C keys to skew your columns to the left and right.

Press the V and F keys to skew your rows to the top and bottom.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your grid and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your grid.

To draw a rectangular grid numerically, choose the Rectangular Grid tool and click once on your artboard to get the Rectangular Grid Tool Options dialog box (see Figure 7.18). Enter the appropriate values and click OK.

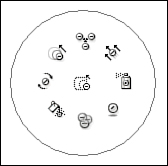

Similar to the Rectangular Grid tool, the Polar Grid tool creates grids that are circular in form.

To draw a polar grid, choose the Polar Grid tool, and click and drag the mouse on the artboard. Before you release the mouse, you can utilize any of the following functions that will affect the grid you are drawing:

Press the Shift key to constrain your grid to a perfect circle.

Press the (Option) [Alt] key to draw your grid out from its center.

Press the up arrow key on your keyboard to add concentric dividers to your grid.

Press the down arrow key on your keyboard to remove concentric dividers from your grid.

Press the right arrow key on your keyboard to add radial dividers to your grid.

Press the left arrow key on your keyboard to remove radial dividers from your grid.

Press the X and C keys to skew your concentric dividers closer to or farther from the center.

Press the V and F keys to skew your radial dividers to the left and right.

Press the spacebar to “freeze” your grid and position it elsewhere on your artboard.

Press the tilde (~) key to create numerous copies of your grid.

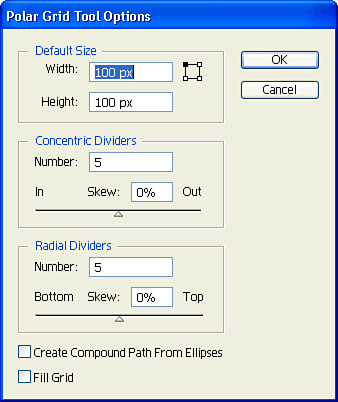

To draw a polar grid numerically, choose the Polar Grid tool and click once on your artboard to get the Polar Grid Tool Options dialog box (see Figure 7.19). Enter the appropriate values and click OK.

For drawing freestyle on your artboard, use the Pencil tool. This tool can be especially useful for sketching if you have a tablet. If you hold down the (Option) [Alt] key as you draw, Illustrator closes the path for you when you release the mouse.

There are several settings for the Pencil tool, which you can access by double-clicking on the Pencil tool itself in the toolbox. The Pencil Tool Preferences dialog box (see Figure 7.20) enables you to edit the Fidelity and Smoothness settings, which affect how clean and smooth your drawn lines will be. The Keep Selected option keeps the last path you’ve drawn with the Pencil tool selected, and the Edit Selected Paths option enables you to simply draw over an existing path to adjust it. Finally, the Fill New Pencil Strokes applies a fill to your pencil strokes after you draw them.

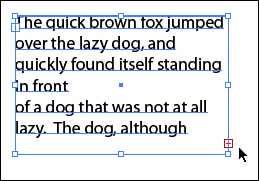

One of the most common tools you’ll use in Illustrator is a Bézier path. Let’s learn what these paths look like and how they work inside Illustrator.

The first type of Bézier path is a straight line; it contains two anchor points with a straight line connecting them (see Figure 7.21). This type is the simplest Bézier path and requires the least amount of memory to store and print—you just need the coordinates of the first and second points.

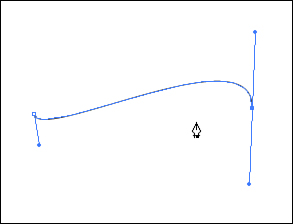

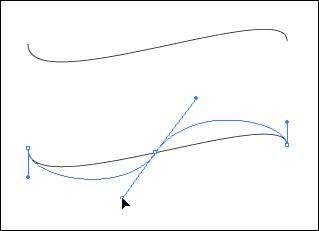

The second type of Bézier path is the curve, and here the description gets complicated. A curve consists of two anchor points, with a curved line connecting them. The curve is determined by control handles, which are attached to each anchor point. The control handles define exactly how the curved line is drawn between the two anchor points (see Figure 7.22).

Of course, when the paths print, you don’t see the anchor points or the handles. They just appear onscreen so you can edit the paths.

Until now, you’ve been creating Bézier paths without even knowing it. The shapes and paths you’ve created are all made up of Bézier paths. You were doing fine until now, so why bring up all of this complicated anchor-point and control-handle information? The answer is, sure, you could perform several tasks in Illustrator without knowing what Bézier paths are, but you lose out on all the power that Illustrator offers. Additionally, both Photoshop and InDesign have the Pen tool and enable you to draw and edit Bézier paths.

Illustrator has three kinds of anchor points: the straight corner point, the smooth point, and the combination point. Each kind of anchor point has its specific attributes, and each is used to create different types of paths. A Bézier object can be made up of any of the three kinds of anchor points and can contain any combination of them as well. For example, a square is made up of four straight-corner anchor points, whereas a circle is made up of four smooth anchor points. A shape such as a pie wedge contains both straight-corner and combination anchor points.

The straight corner is the simplest form of the anchor point, and it is primarily used to connect straight lines (see Figure 7.23). To draw straight lines, press P to switch to the Pen tool and click once on your screen to define the first point in your line. Now click where you want the second point to appear (don’t drag from the first point—just click and release). Each time you click in a different place, Illustrator draws a line connecting the anchor points. To create a closed shape, click on the first anchor point (the Pen tool icon appears with a little O next to it when you’re about to close a path).

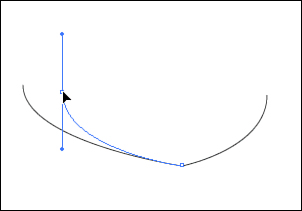

The smooth anchor point contains two control handles (see Figure 7.24). By adjusting the control handles, you determine the slope and sharpness of the curve on either side of the point. Because the path continues through the point without a sharp change in direction, it is called a smooth anchor point.

To draw curved lines, click and drag the mouse with the Pen tool to create your first point. Notice that as you drag, you’re pulling control handles out from the point. Release the mouse button and then click and drag again at a different place on your artboard. As you drag, you’ll see control handles being created for the second point, and a curved line will appear between the two points.

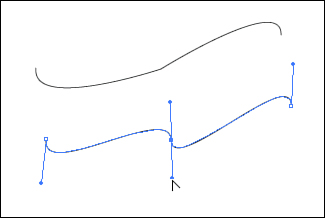

The combination anchor point is a combination of the straight anchor point and the smooth anchor point (see Figure 7.25), so using these types of points can get a bit confusing. To draw a path using a combination point, click and drag with the Pen tool to create a smooth point. Then just click elsewhere on the screen to create a corner point. Then click and drag again elsewhere to create yet another smooth point.

You’ll notice that the point in the middle has no control handles, yet it has curved paths connected to it. In reality, the combination point has two sides to it: a straight side (from the single click) and a curved side (from the click and drag).

After you draw a path, you might want to change the shape or style of the points, adjusting the curve of the path or making a corner point into a smooth point. Several tools enable you to modify a path by changing, adding, or deleting a point.

Perhaps the simplest method of editing a path is to use the Direct Selection (hollow arrow) tool. By selecting only one anchor point, you can reposition it (see Figure 7.26). By selecting a path and then dragging on a control point, you can change the shape of the curve for that path.

Simple in concept, the Add Anchor Point tool—which looks just like the Pen tool with a little + (plus sign) next to it—enables you to place additional anchor points on an existing path (see Figure 7.27). Each new point takes on the attributes of the path on which you click. If you add a point to a straight path, the new anchor point is a straight anchor point, and clicking a curved path results in a new smooth anchor point.

The Delete Anchor Point tool simply deletes existing anchor points. It also looks just like the Pen tool, except that it has a minus sign (–) next to it. If you click an anchor point with the Delete Anchor Point tool (see Figure 7.28), the point is removed, and Illustrator automatically joins the preceding anchor point with the next point on the path. If you were to select an anchor point and press the Delete key on your keyboard, the anchor point would be deleted, but the path would be broken at that point.

What do you do when you already have an anchor point, but you need to change it from one type of point to another? You use the Convert Anchor Point tool. You can easily access this, the last tool from the Pen tool quartet, by pressing (Option) [Alt] when any of the Pen tools is active. Notice that the cursor changes to an inverted V shape.

This tool works the same way as the Pen tool; clicking a point converts it to a straight anchor point. Clicking and dragging on a point makes that point a smooth anchor point. To make a smooth point into a combination point, click and drag on a control handle (see Figure 7.30).

When you create paths, they aren’t always as clean or as smooth as you might like, especially when using the Pencil tool and drawing with a mouse. The Smooth tool (grouped with the Pencil tool) enables you to “get the kinks out” and get a smooth vector path. Use the tool to draw over any part of a selected path to smooth out that section of the path.

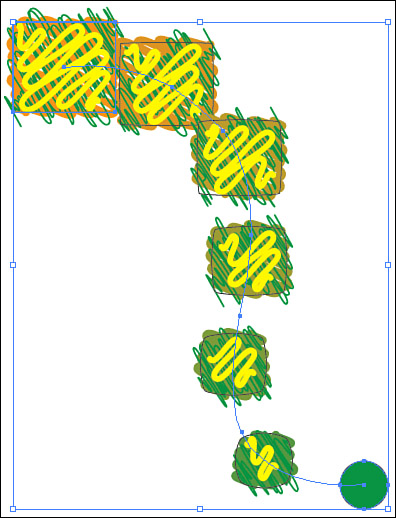

Sometimes a shape has many extra anchor points (as a result of autotracing, or an autotrace program such as Adobe Streamline). Sometimes entire paths need to be smoothed out as well. Although you can use the Smooth tool for certain applications, as mentioned previously, sometimes you want to apply those effects on a larger scale.

With any path or object selected, you can choose Object, Path, Simplify to remove extra anchor points and smooth out vector paths. You can specify that only straight lines be used (no curves), and you can also choose to show a preview of the original path, to compare how close the new simplified path will be to the original (see Figure 7.31). Making adjustments to the Curve Precision and Angle Threshold sliders will control how many anchor points are removed and how smooth the result will be.

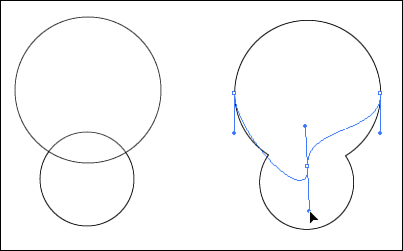

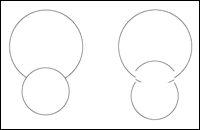

No doubt you had more fun drawing the simple shapes discussed earlier than you did trying to make sense of the likes of the Pen tool. When it comes to creating more complex shapes, however, you can still use the primitive shape tools that are easy to use, along with a powerful collection of functions called Pathfinder. In fact, these functions are so useful that they have their own panel.

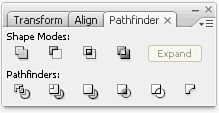

The idea behind the Pathfinder functions is that you can use several simple shapes to create a single, more complex shape. The Pathfinder panel is split into two rows of functions. The buttons on the top row are called Shape Modes, and they enable you to add, subtract, intersect, and exclude shapes. The buttons on the bottom row are referred to as Pathfinders, and they enable you to divide, trim, merge, crop, outline, and apply a Minus Back function (see Figure 7.32).

The shape modes are used primarily to create complex shapes from two or more other paths. To use these functions, you simply select the shapes you want to affect and click on the appropriate shape mode. There are four shape modes in Illustrator CS3:

Add—. The most commonly used command, the Add shape mode combines all the selected objects into one object (see Figure 7.33).

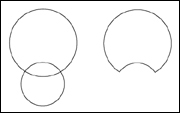

Subtract—. The Subtract shape mode subtracts the frontmost object in your selection from the shape behind it, leaving a hole cut out of it (see Figure 7.34).

Intersect—. The Intersect shape mode is used on two or more objects that overlap each other. When it’s applied, only the area where the objects overlap remains. The other parts of the objects are not visible (see Figure 7.35).

Exclude—. The Exclude shape mode is the exact opposite of the Intersect shape mode. When it’s applied to overlapping objects, only the parts that don’t overlap remain visible (see Figure 7.36).

Shape modes are nondestructive, meaning that you can continue to edit the primitive shapes after you’ve applied a shape mode. Objects that have shape modes applied to them are called compound shapes. You can use the Direct Selection tool to select parts of a compound shape to edit them (see Figure 7.37).

If at any time you want to “flatten” a compound shape so that the individual primitive shapes are no longer accessible, select the compound shape and click on the Expand button in the Pathfinder panel (see Figure 7.38). Alternatively, if you want to create a flattened object to begin with, you can press and hold the (Option) [Alt] key while applying any of the shape modes.

The Pathfinder functions are primarily used for splitting objects into parts or deleting unwanted parts of objects. There are several kinds, each with a different purpose:

Divide—. The Divide Pathfinder cuts up any overlapping shapes into separate shapes wherever they overlap (see Figure 7.40). An invaluable tool, Divide enables you to split up objects quickly. Divide looks at each object and divides each overlap individually, so it makes no difference whether you’re dividing compound paths, groups, or whatever—they all become individual shapes. After Divide is applied, all the resulting objects are grouped together. You have to ungroup them if you want to work with each piece separately (or use the Direct Selection tool).

Trim—. The Trim function removes the parts of the back object that are behind front objects. It also removes the stroke (see Figure 7.41).

Merge—. The Merge function operates differently, depending on the fills of the selected objects. If the fills are all the same, the result is similar to what’s achieved with the Add shape mode, making the objects form one single (flattened) object. If the fills are all different, Merge works like the Trim function. If some of the objects are filled the same, the like objects are united and the rest are trimmed (see Figure 7.42).

Crop—. The Crop function removes any parts of selected objects that are not directly under the frontmost object (see Figure 7.43). The final result of the Crop function is similar to what you would see if you created a mask. The only difference is that the Crop function actually deletes the art that is not visible, unlike a mask, which just covers it up. Be careful before you run this command because you cannot retrieve the artwork that is cropped out.

Outline—. Choosing the Outline function converts all shapes to outlines and also divides the lines where they intersect, similar to a Divide function for strokes (see Figure 7.44).

Minus Back—. The reverse of the Subtract shape mode, Minus Back subtracts a part of an object based on what’s behind it (instead of what’s in front of it). This function is also not a shape mode, so the final result is a single flattened object (see Figure 7.45).

In typical paint programs, you use selection tools to select pixels. In Illustrator, things are a bit different—rather than pixels, we’re primarily interested in objects. Illustrator has several selection tools and selection methods, so let’s take a look at them.

The Selection tool (or the black arrow, as I like to call it because of its appearance) is used to select entire objects. You select an object simply by clicking on it. When an object is selected, you can move it by dragging the object.

You can select multiple objects by holding down the Shift key as you click on other objects.

The Shift key technique can really save time when you’re making certain selections, such as when you want to select all objects in your file except for one of them. In this case, you can simply select all and then Shift+click the one you want to deselect, and you’re done.

Another method of selecting objects with the Selection tool is called marquee selecting, in which you click on a blank area and then drag the mouse while holding down the mouse button. As you drag the mouse, a box appears. Any objects that fall within the marquee box become selected when you release the mouse button (see Figure 7.46). It’s almost like catching fish with a net.

The Direct Selection tool (or as I like to call it, the white arrow) is the selection tool used the most in Illustrator. In a few moments, you will see why. As you just learned, the Selection tool is used to select entire objects. The Direct Selection tool, on the other hand, is used to select parts of an object. If you click on a path and drag, only that path moves. The same applies when you click on an anchor point—only that anchor point moves (see Figure 7.48).

You can use either the Shift+click method or the marquee method to select multiple anchor points and move them at the same time.

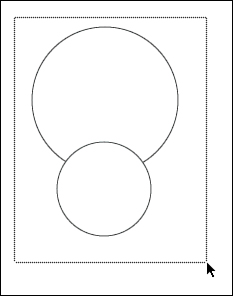

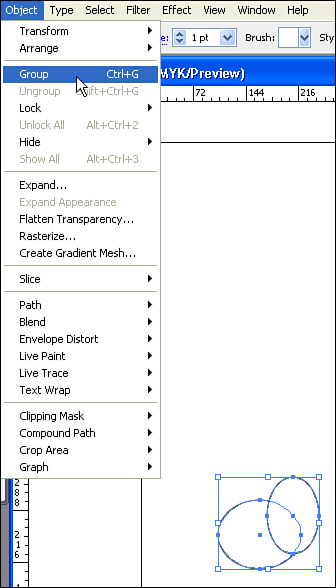

Illustrator enables you to group several objects to make it easier to organize your artwork. However, the benefits of grouping objects go far beyond having art that is “neat” or organized. First, when you use the Selection tool to select one object in a group, the entire group is selected. This makes it easier to move objects around. Second, a group itself can have certain attributes or effects applied to it. Finally, groups can be nested. That means you can have a group inside another group (and so on).

To make a group, select the objects you want to group, and choose Object, Group (see Figure 7.49). To release a group, select it and choose Object, Ungroup.

Groups are extremely helpful when you are working in complex documents, and grouping items as you create them is always a good idea. After you create a logo, for instance, group it. This way, you can move it around easily, and, more important, you won’t accidentally lose parts by trying to select each piece every time (inevitably, you’ll miss one or two parts).

When you double-click on any object in a group using the Selection tool, a gray box appears at the top of the window (see Figure 7.50). This gray box indicates that you’re in group isolation mode, and any new shape that you now draw automatically becomes part of the group. To get out of group isolation mode, click the arrow in the box. We talk more about group isolation mode when we cover Live Paint, later in “Live Paint Groups.”

The Group Selection tool is a variation of the Direct Selection tool. It is grouped with the Direct Selection tool and can be found by pressing and holding the mouse button on the Direct Selection tool in the toolbox. In complex illustrations, you might have nested groups that contain many groups. The Group Selection tool makes working with these groups easy.

Each time you click with the Group Selection tool, it selects the next higher group, giving you easy access to any group with a nested group.

As mentioned earlier, the Direct Selection tool is the most-used selection tool in Illustrator. If you switch back to the Direct Selection tool and press and hold the (Option) [Alt] key, you’ll notice that the cursor for the Direct Selection tool on your screen turns into the Group Selection tool. Releasing the (Option) [Alt] key returns you to the Direct Selection tool.

Now you have the power to select parts of an object, or, by simply holding down the (Option) [Alt] key, you can select an entire object or entire groups of objects. For 90% of your work, you never have to go back to the Selection tool (black arrow).

Using the marquee method for making selections with the Selection and the Direct Selection tools can be useful, but only if you’re okay with selecting objects that fall into a rectangular marquee area. The Lasso tool enables you to draw irregularly shaped marquees to select objects or parts of objects.

The Lasso tool works much like the Direct Selection tool, in that if an object falls completely within the boundaries of the marquee, the entire object becomes selected. But if only a portion of the object falls into that marquee area, only that portion of the object becomes selected (see Figure 7.51).

To use the Lasso tool, choose it from the toolbox and draw a marquee area. You don’t have to complete the marquee by drawing back to the point you started from because the Lasso tool completes the marquee selection area after you release the mouse.

Photoshop has a Magic Wand tool that’s used to select pixels of similar color. Likewise, in Illustrator the Magic Wand tool is used to select objects of similar attributes. Double-clicking on the Magic Wand tool in the toolbox opens the Magic Wand panel, where you can specify a Tolerance setting and specify to which attributes the Magic Wand is sensitive (see Figure 7.52).

Illustrator wouldn’t be incredibly useful if it were capable of creating only shapes with white fills and black strokes. It’s time to splash a bit of color on the topic of applying fills and strokes to objects in Illustrator.

You can specify colors for selected objects in Illustrator by using the Color panel. When expanded fully, the Color panel contains a fill and stroke indicator, color sliders, and a color ramp (see Figure 7.53). To specify a color for the fill of an object, you have to click on the fill indicator first. Likewise, to specify a color for the stroke of an object, click on the stroke indicator.

The Color panel can define colors in Grayscale, RGB, HSB, CMYK, and Web-safe RGB color modes. To switch among these color modes in the Color panel, choose from the list in the panel flyout menu (see Figure 7.54). Alternatively, you can Shift+click on the color ramp to cycle through the different supported color modes.

You can store saved colors in the Swatches panel (see Figure 7.55). To create a swatch, simply drag a color from the stroke indicator or the fill indicator in the Color panel into the Swatches panel. Illustrator also ships with numerous swatch collections, which you can access by choosing Open Swatch Library from the Swatches panel flyout menu.

You can create basically three kinds of swatches inside Illustrator: solid colors, gradients, and patterns.

Solid colors are simple and are really prerequisites for the other types of swatches. You can define a solid color just as mentioned previously, by specifying a color in the Color panel. However, you need to be aware of really two types of solid colors: process colors and spot colors.

A process color, by definition, is a color made up of a mix of colors. In the print world, a process color is one made up of different values of CMYK. In the Web arena, Illustrator would also consider an RGB color a process color.

You specify a process color for jobs you’d be printing in four-color process or publishing on the Web.

A variation of the process color, called a global process color (see Figure 7.56), enables you to easily track and update colors throughout your document.

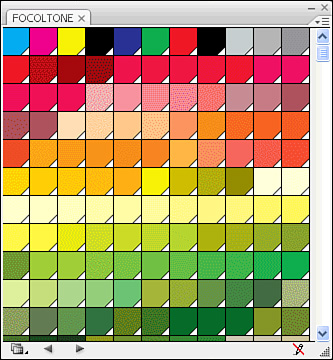

A spot color is a predefined ink color that you can either specify on your own or choose from a list such as Pantone, Focoltone, or Toyo. Spot colors also are referred to as custom colors. They are standard colors that have been designated to ensure color accuracy.

Spot colors have a single value, or a tint value, that determines the strength at which the ink will be printed. Spot colors are usually specified when you want to print a specialized ink (a metallic color, for example) or when you want to save money by printing a two- or three-color job (instead of having to print a full process–color job).

Illustrator ships with many standard custom color libraries, all of which you can load by choosing Open Swatch Library from the Swatches panel flyout menu.

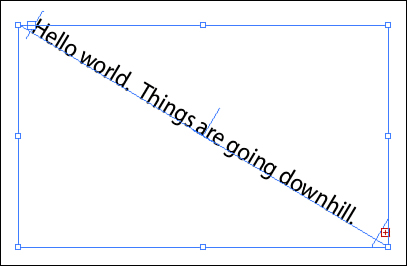

Gradients are a powerful feature in Illustrator, enabling you to specify a fill of different colors blending with each other. Illustrator can create a gradient between just 2 colors or up to 32 colors. Gradients can be used to achieve cool shading effects or to add dimension to objects (see Figure 7.57).

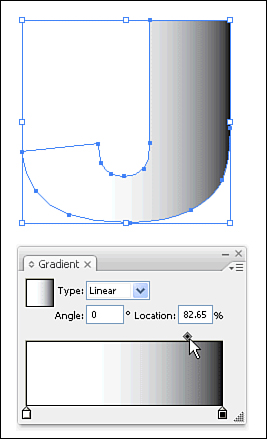

You can apply a gradient to a selected object simply by selecting a gradient swatch from the Swatches panel. To create or edit a gradient, however, you need to open the Gradient panel. With the panel expanded fully, you will find a gradient swatch, an option to make the gradient linear or radial, fields for Angle and Location, and a gradient slider (see Figure 7.58).

You create a gradient in much the same way you create a color. Click on the Gradient swatch in the Gradient panel. Notice that under the gradient slider are icons that look like little houses. They are color stops, indicating the points at which a color is used in the gradient. To create a new color stop, click anywhere beneath the gradient slider. When a new color stop appears, you can drag it to the left or right. You can also drag any color from the Swatches or Color panel onto the gradient slider to create a color stop in that color. To change an existing color stop, either drag a new color directly on top of it, or click the color stop icon to select it and choose a new color in the Swatches or Color panel.

Notice also that little diamond-shape icons appear on top of the gradient slider. These indicate the location of the midpoint of the gradation. In other words, wherever the icon is, that’s the place where 50% of each color appears. You can drag the midpoint indicator left or right to adjust where the midpoint should be (see Figure 7.59).

After you’ve created the perfect gradient, click the New Swatch icon in the Swatches panel. After you create the new swatch, you should double-click it and give it a name. Illustrator gives your creations the names New Gradient Swatch 1, New Gradient Swatch 2, and so on, which don’t really offer any insight into what they are.

The Gradient tool in Illustrator is used to control the direction and placement of a gradient in an object or over several objects. After you fill an object with a gradient, select the Gradient tool and, with the object still selected, click and drag across the object in the direction you want the gradient to go (see Figure 7.60). The place where you begin dragging is the position where the gradient starts, and the place where you let go is the position where the gradient ends. If you stop dragging before you get to the end of the object, Illustrator continues to fill the object with the color at the end of the gradient.

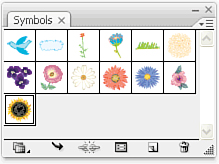

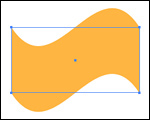

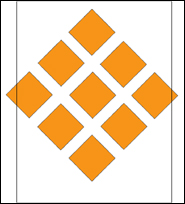

Patterns can be real time savers. A pattern is a defined piece of art, or tile, created in Illustrator that, as a fill attribute, is repeated over and over again, much like wallpaper (see Figure 7.61).

Defining a pattern is a little different from defining gradients or colors. Instead of clicking the New Swatch icon, you drag your objects directly into the Swatches panel from the artboard. After you create a pattern swatch, remember to give it a unique name so you can identify it quickly when you need it.

When you’re creating a pattern design, remember that your object will be repeated over and over again, so be careful how you set it up. If you need extra space around your art (which is usually the case), create a rectangle and send it to the back of your artwork. Then select your art, along with the empty box in the background, and define the pattern. Illustrator treats a rectangle that’s at the bottom of the stacking order as a boundary for the repeat area of the pattern.

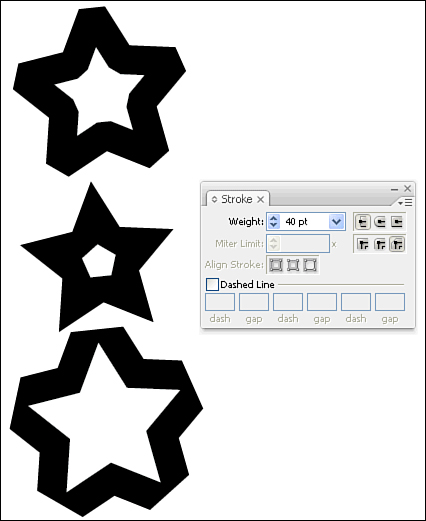

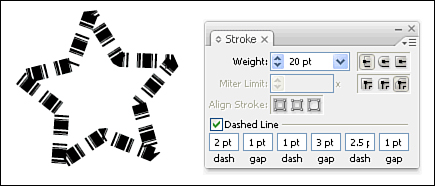

A stroke is the line that’s drawn around an object, and you can specify solid colors, gradients, or patterns to color a stroke. The Stroke panel is where you can control the actual settings for how a stroke appears (see Figure 7.62).

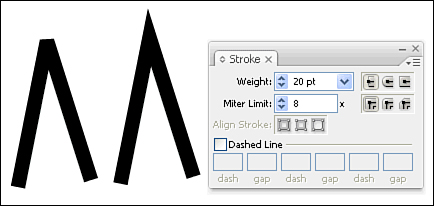

The most-used option in the Stroke panel is Weight. It determines how thick or thin the stroke is. Illustrator’s default is 1 point. For hairline rules, most people use 0.25 point (anything thinner probably won’t show up on an offset printing press).

The Miter Limit option determines how far the stroke protrudes on a sharp corner. A thick line, for example, needs more room to complete a sharp point than a thin one does (see Figure 7.63).

Line caps determine the appearance of the ends of a stroked path (see Figure 7.64). This setting in the Stroke panel is used only for open-ended paths. By choosing different caps, you can make the ends either flat or rounded, or have the stroke width enclose the end of the path as well.

Line joins control how the stroke appears at each corner of the path (see Figure 7.65). You can choose from Mitered, Round, and Beveled options.

By default, Illustrator draws the weight of a stroke on the center of a path. That means a 20-point stroke results in 10 points applied to the inside of the path and 10 points to the outside of the path. However, you can use the Align Stroke buttons in the Stroke panel to specify that the weight of the stroke be applied entirely inside the path or entirely outside the path (see Figure 7.66).

The last option in the Stroke panel, Dashed Line, can be one of the most powerful. Here you can specify dashed or dotted lines. Depending on what settings you have set for weight, line caps, and line joins, you can create a stitched line, a skip line, or almost anything. You control the dash and gap (the space between each dash) by entering numbers into the Dash and Gap fields at the bottom of the panel. If you’re using only one sequence, you can enter just the first two fields. Alternatively, you can enter up to three Dash and Gap settings to achieve complex dash patterns (see Figure 7.67).

For outlining and special effects, Offset Path is a great function. Offset Path creates an object that perfectly outlines, or traces, a selected path at an offset that you specify. To use it, select one or more objects and choose Object, Path, Offset Path. The Offset Path dialog box then appears. Enter an amount for the offset (you can use positive or negative numbers) and click OK. Note that Offset Path always makes a copy of your selection and does not affect the original.

Outline Path is another great feature that converts strokes into filled objects. Found in the same location as the Offset Path command, Outline Path works by creating a filled shape the size of the stroke width.

We’ve discussed groups, but Illustrator also has a special kind of group called a Live Paint group. Ordinarily, coloring objects in Illustrator requires the careful creation of closed vector shapes. For example, if you were to draw a tic-tac-toe board using four straight lines (see Figure 7.68), there would be no easy way to fill the middle section with a color, even though it appears to be a closed area. With Live Paint however, you can do so.

With the four lines selected, you could select the Live Paint Bucket tool (a paint bucket pouring into a small square) and then click on any of the paths to convert them to a Live Paint group. In a Live Paint group, any area on your screen that looks like a closed shape acts like one. You can then choose a color from the Swatches panel and click on the center region of the art with the Live Paint Bucket tool to fill the area. As you move the Live Paint Bucket tool, areas that can be filled with color are highlighted (see Figure 7.69).

Live Paint groups are also easier to use when making edits. You can switch to the Selection tool and double-click on the group to enter group isolation mode. Then you can use the Line tool to draw a new line through the middle of the group. Using the Selection tool, double-click outside the group to exit group isolation mode. You can use the Live Paint Bucket tool to apply color to the dissected regions.

The Live Paint Selection tool enables you to select regions or segments of paths and even delete them.

When creating freestyle art, there are sometimes gaps between the paths because not every path lines up perfectly. You might want to fill a region with color even if the region isn’t visibly closed. With a Live Paint group selected, you can choose Object, Live Paint, Gap Options, to specify that gaps of a certain size (which you define) will automatically close when creating filled areas (see Figure 7.70).

At any time, you can also expand a Live Paint group by selecting the group and choosing Object, Live Paint, Expand. This returns the objects to normal Illustrator vector objects.

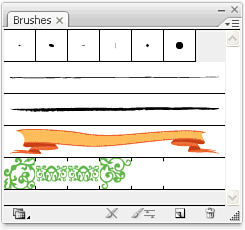

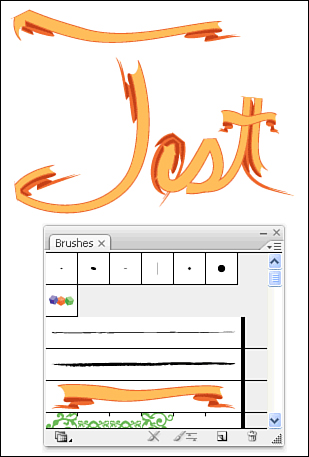

Illustrator includes four kinds of brushes, all applied in the same way. The traditional way to apply a brush in Illustrator is to use the Paintbrush tool, which works similarly to the Pencil tool. Instead of just drawing a plain stroked path, the Paintbrush tool applies one of the four kinds of brushes.

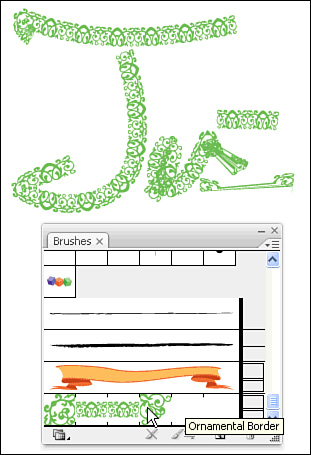

Brushes are stored in the Brushes panel (see Figure 7.71), and the truth is that you don’t need to use the Paintbrush tool to apply a brush at all. That’s because you can select an existing object and click on any brush in the Brushes panel to apply that brush stroke to the selected path. Of course, the Brush tool makes it easier to create more artistic brush strokes, but as you’ll soon see, certain kinds of brushes don’t require that kind of artistic touch.

The first kind of brush is the Calligraphic brush. A calligraphy pen has an angled tip, or nib, which, when used to draw or write, creates a tapered line that gets thicker or thinner, depending on the angle and direction of the stroke. The Calligraphic brush simulates this effect (see Figure 7.72).

To create a new Calligraphic brush, click on the New Brush icon in the Brushes panel and choose New Calligraphic Brush to get the Calligraphic Brush Options dialog box (see Figure 7.73).

In the Calligraphic Brush Options dialog box, you can specify the following settings:

At the top of the box, you can specify a name for the brush.

Directly under the name is a white box with a picture of an ellipse with an arrow going through it and two black dots on either side. This is the Brush Shape Editor. Simply click and drag on the arrow to rotate the brush shape and adjust its angle. Click and drag inward on the black dots to adjust the roundness of the brush shape.

To the immediate right of the Brush Shape Editor is an area that shows you a preview of your brush shape. Notice the three shapes, of which the outer two are grayed out and the center one is black. If you have variations set (see the next bullet item), the gray shapes illustrate the minimum and maximum values for the brush shape.

You can specify values for angle, roundness, and diameter numerically at the bottom of the dialog box. Each option can have one of three variation attributes: Random, in which Illustrator randomly changes the setting; Pressure, which enables you to determine brush shape by how hard you press with a pressure-sensitive pen and tablet; and Fixed, which assigns a constant value that you define.

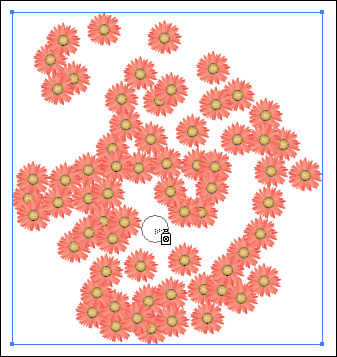

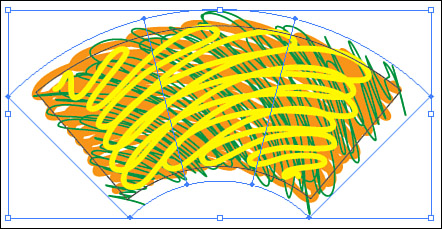

The Scatter brush distributes predefined art along the path you draw with the Paintbrush tool (see Figure 7.74). To define a new Scatter brush, you have to start with a piece of art. When you’ve created the art you want to use for the brush, select the art and drag it into the Brushes panel. When the New Brush dialog box appears asking what kind of brush you want to create, choose New Scatter brush and click OK.

Illustrator then opens the Scatter Brush Options dialog box, where you can specify the behavior of the new Scatter brush (see Figure 7.75).

In the Scatter Brush Options dialog box, you can specify the following settings:

At the top of the box, you can specify a name for the brush.

Directly under the name are four options for which you can enter numerical values to specify the size of the art when it’s drawn on the path; the spacing between the art as it appears on the path; the scatter, which defines how far from the path the art can stray; and, finally, the rotation, which specifies the rotation of each individual piece of art on the path. You can set the rotation to be relative to the page or to the actual path itself. For each of these four settings, you can specify Fixed, Random, or Pressure, just as you could for the Calligraphic brushes. The Pressure option works only if you are using a pressure-sensitive tablet, such as a Wacom tablet.

The final option for the Scatter brush is Colorization. This option enables you to specify color changes to the art that appears on your painted strokes. Choosing None keeps the color consistent with the original color defined with the brush you have selected. To use the Hue Shift option, click the Eyedropper box, and click to choose a color from the art that appears in the box to the right. This procedure works on colored objects only, not black-and-white objects. Clicking the Tips button can help you see how the color changes are applied.

If you’re thinking that the Scatter brush seems similar to the brushes you created in Photoshop, you’re absolutely right. As you’ll see in “The Symbolism Tools,” there’s a more powerful feature in Illustrator, the Symbol Sprayer tool, that can create art that looks similar to the Scatter brush.

The Art brush differs from the Scatter brush in that the Art brush stretches a single piece of predefined art along a path (see Figure 7.76), whereas the Scatter brush litters the path with many copies of the art.

To define a new Art brush, you have to start with a piece of art. After you’ve created the art you want to use for the brush, select the art and drag it into the Brushes panel. When the New Brush dialog box appears asking what kind of brush you want to create, choose New Art Brush and click OK.

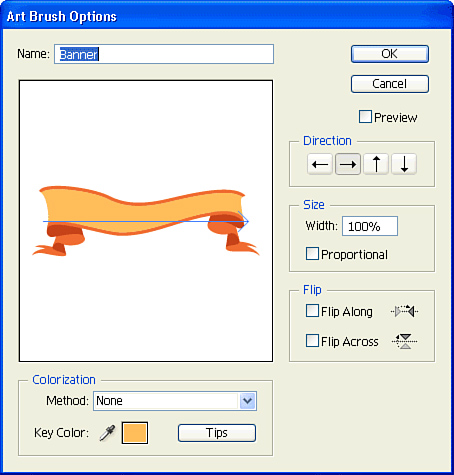

Illustrator then opens the Art Brush Options dialog box, where you can specify the behavior of the new Art brush (see Figure 7.77).

In the Art Brush Options dialog box, you can specify the following settings:

At the top of the box, you can specify a name for the brush.

Directly under the name is a white box with the art in it. Notice that an arrow goes through the art. This arrow indicates the direction the art is drawn on the path; you can edit it by clicking any of the arrows that appear to the right of the white box.

Below the Direction option is the Size option, in which you can specify what size the art appears on the painted path. If you select the Proportional option, the artwork retains is height-to-width relationship for the length of the stroke. You can also specify whether the art should be flipped along or across the painted path.

The final option for the Art brush is Colorization, which functions exactly like the Scatter brush does, as described earlier.

Apparently, three kinds of brushes in Illustrator just weren’t enough for the engineers over at Adobe, so they added a fourth—arguably the most powerful of the bunch. The Pattern brush applies patterns across a painted path (see Figure 7.78). What makes this different from any brush until this point is that you can define patterns with different attributes for corners and ends. We covered how to create patterns earlier in the chapter; when you have your patterns listed in your Swatches panel, you can define a Pattern brush by clicking on the New Brush icon in the Brushes panel and choosing New Pattern Brush.

Illustrator then opens the Pattern Brush Options dialog box, where you can specify the behavior of the new brush (see Figure 7.79).

In the Pattern Brush Options dialog box, you can specify the following settings:

At the top of the box, you can specify a name for the brush.

Directly under the name are five boxes, each representing a different tile of the pattern: Side, Outer Corner, Inner Corner, Start, and End. You do not need to define all five parts, and Illustrator uses the parts only when necessary. With a tile section selected, choose a pattern from the list that appears directly under the tiles.

As with the previous brushes, you can specify Scale and Spacing, as well as specify whether the pattern should be flipped along or across the path.

With the Pattern brush, you can decide how Illustrator fits the pattern to the path. Obviously, not every pattern will fit every path length perfectly. If you select Stretch to Fit, Illustrator stretches the pattern tiles to make the pattern fit seamlessly across the entire painted path. If you select Add Space to Fit, Illustrator does not adjust the size of the pattern tiles, but spaces them evenly across the painted stroke. Finally, the Approximate Path option adjusts the size of the path itself to fit the size of the pattern tiles.

The final option for the Pattern brush is Colorization, which functions exactly as it does for the Scatter and Art brushes, as described earlier.

In closing, if you find it hard to identify each brush type just by looking at the Brushes panel, you can opt to view the brushes by name. Choose List View from the Brushes panel flyout menu, and an icon on the far right of each brush listing indicates the brush type (see Figure 7.80).

Using layers in Illustrator enables you to better organize the objects in your file. Although it might not make much sense to spend time creating and working with layers to work on a simple logo, it certainly makes sense for illustrations or designs that are more complex.

Illustrator’s layers are specified in the Layers panel. When you start working in a new document, all artwork is automatically placed on a layer called Layer 1 (see Figure 7.81). To open the Layers panel, choose Layers from the Window menu. The order in which layers appear in the Layers panel is important: Layers that appear closer to the top of the panel appear above (or in front of) other objects that might appear on layers that are closer to the bottom of the Layers panel.

Some artists prefer to create several layers before they begin working, adding art to each layer as they progress. Others prefer to add or delete layers as necessary as they work on a project. Still others like to create the entire piece and then chop it into different layers afterward. As you’ll soon see, there are certainly some benefits to working with layers during the design process (instead of after the fact).

To create a new layer, click on the New Layer button at the bottom of the Layers panel. Illustrator creates the layer and assigns it a name. You can double-click on the layer to rename it, or instead you can (Option-click) [Alt+click] on the New Layers button to create a new layer and name it in one step. In either case, it’s a good idea to name your layers because trying to identify layers that are named Layer 1, Layer 2, Layer 3, and so on is difficult (to say the least).

To delete a layer, either click the layer in the Layers panel to highlight it and then click on the Trash icon at the bottom of the panel, or drag the layer itself onto the Trash icon. If you try to delete a layer that contains artwork on it, a warning dialog box appears, alerting you about the situation; Illustrator deletes the layer and its contents only with your permission.

You can duplicate a layer—and all the contents of that layer along with it—by clicking and dragging an existing layer onto the New Layer icon in the Layers panel.

As I mentioned earlier, there are certainly benefits to working with the Layers panel as you design your art. Let’s take a closer look at the Layers panel to better understand these benefits.

Each layer in the Layers panel has several icons, which enable you to perform certain functions (see Figure 7.82). We discuss these functions beginning on the far left of a layer listing.

On the far left, each layer has an icon that looks like an eye. Clicking on the eye toggles the visibility of that layer. Pressing the (Option) [Alt] key while clicking on the eye hides/shows all other layers at once.

The next icon to the right of the eye is a lock indicator. Click in the box to toggle the layer to be locked or unlocked. Pressing the (Option) [Alt] key while clicking on the lock locks/unlocks all other layers at once.

The next icon to the right of the lock is a disclosure triangle. Click on the triangle to reveal the contents of the layer. If there isn’t a triangle on a layer, there are no objects on that layer.

To the right of the disclosure triangle is a thumbnail icon that gives a graphical preview of the objects on that layer. Be aware that for documents with many layers, thumbnails can slow the performance of Illustrator because it has to draw each and every thumbnail.

To the right of the thumbnail is the layer name.

To the right of the layer name is a little circle. This is the target icon. For an effect or attribute to be applied to an object in Illustrator, that object (or group or layer) has to be targeted. Illustrator actually employs something called smart targeting that automatically does the targeting for you; however, sometimes you want to specifically target something yourself. To target a layer or an object, click once on the circle icon, which then appears with a circle outlined around it. Layers or objects that have an appearance applied to them display the circle as a shaded 3D sphere (which the Adobe engineers refer to as the “meatball”).

Finally, if you click on the far right of the layer, it selects all the objects in that layer. Selections are indicated by a colored square. This square can appear in two sizes. If all the objects on the layer are selected, you will see a large square, but if only some of the objects on a layer are selected, a smaller square displays. You can move artwork from one layer to another simply by dragging the colored square to a different layer. You can press the (Option) [Alt] key while dragging the square to copy the selected art to a different layer.

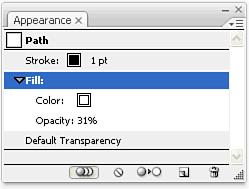

Ask me what I think the key is to getting a real grasp on using Illustrator, and I’ll tell you it’s the Appearance panel. That’s because the Appearance panel gives you the information you need to know about your targeted selections. For example, if you select a rectangle, the Appearance panel tells you that a path is targeted and indicates what the fill and stroke of that object are. More important, the Appearance panel tells you whether transparency settings or live effects have been applied to the object (see Figure 7.83). Later in “Live Effects” we cover exactly what live effects are, but examples are a soft drop shadow and a warp effect.

The Appearance panel also enables you to add multiple strokes or multiple fills to an object, a group, or a layer. To do so, simply choose Add New Fill or Add New Stroke from the Appearance panel flyout menu.

We’re going to be looking at the Appearance panel a bit more closely in “Live Effects,” but I wanted to point out that, just as with the Layers panel, items that appear in the Appearance panel represent the stacking order for those items. By default, an object’s stroke appears above the fill, but you can actually change that in the Appearance panel by dragging the fill to appear at the top of the stacking order. Following the same line of thinking, you can click on just the fill to highlight it and then apply an opacity setting that will be applied only to the fill, not to the stroke of that object (see Figure 7.84).

A mask conceals, or covers, parts of an object behind it, yet it reveals parts of the object behind it as well. For example, a mask that you wear to a masquerade party might cover parts of your face, yet some parts might not be covered. A mask in Illustrator works in much the same way: You can use just about any shape or object in Illustrator to mask other elements in your design. After a mask is applied, you can edit the art behind the mask or the mask itself, independently of each other.

You can apply basically three types of masks in Illustrator: a clipping mask, a layer clipping mask, and an opacity mask. Each of these masks has its own specific uses and capabilities.

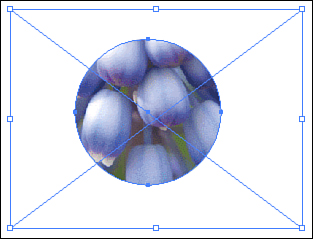

The clipping mask, the simplest kind of mask in Illustrator, can be made of any vector shape. A clipping mask works in this way: You have a shape that sits on top of your objects. When the mask is created, any objects that fall within the boundary of the top shape (the mask) are visible, but anything that falls outside that boundary is hidden. It’s important to realize that the hidden art is not deleted—it’s still there, but it’s hidden from view.

To create a clipping mask, draw a shape for your mask and bring it to the front of the stacking order. Position your mask over the art you want the mask to affect and select both the art objects and the mask shape above it (see Figure 7.85). Then choose Object, Clipping Mask, Make to create the mask (see Figure 7.86). When the mask is applied, both the objects and the mask above it are grouped together; however, you can use the Group Selection tool to select just the mask or just the objects to make edits. This is useful when you want to reposition the mask to reveal a different part of the objects below it.

To release a mask (and have all the objects below the mask revealed again), select the group of the mask and objects, and choose Object, Clipping Mask, Release.

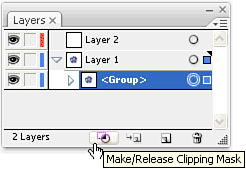

Layer clipping masks are very similar in concept to clipping masks, except that they are applied in the Layers panel and affect all items on a specific layer. To create a layer clipping mask, simply create a shape that’s on the same layer as the art you want to mask, and click on the layer listing in the Layers panel to highlight it. Then click the Make/Release Clipping Mask button at the bottom of the Layers panel (see Figure 7.87).

Any object you add to that layer automatically becomes masked as well. Likewise, any object you pull out of that layer no longer is masked. A mask object is indicated by a listing in the Layers panel with an underline. To release a layer clipping mask, highlight the layer in the Layers panel and click the Make/Release Clipping Mask button.

As Emeril Lagasse says, let’s kick it up a notch! Opacity masks are like clipping masks on steroids. First of all, you can use just about anything as an opacity mask—even gradients and photographs.

The same basic rules for clipping masks apply to opacity masks, in that you place the mask at the top of the stacking order and then select both the mask and objects under it before applying the mask.

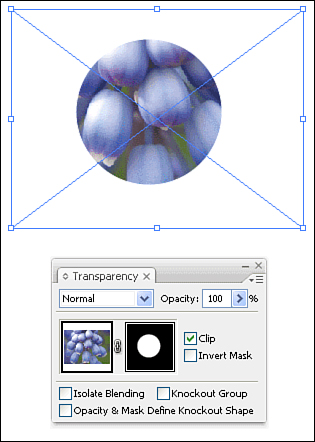

When you have the objects selected, open the Transparency panel and expand the panel so you can see all the options. You’ll see a thumbnail of your selection on the left side of the panel. From the Transparency panel flyout menu, choose Make Opacity Mask. You’ll now see that a second thumbnail appears in the Transparency panel beside the original one, which is the mask itself (see Figure 7.88).

After an opacity mask is applied, you have several options in the Transparency panel:

To edit the art, click on the left thumbnail. You can tell that the thumbnail is highlighted if you see a black outline around it. Any edits you make on the artboard will affect the art objects themselves, and there’s no way for you to access or edit the mask object itself.

To edit the mask object itself, click on the right thumbnail. There are two ways you can tell that you’re editing the mask itself and not the art under it. The mask thumbnail is highlighted with a black outline, and the Layers panel changes to display only a single item—the opacity mask itself (see Figure 7.89). While you’re editing an opacity mask, you cannot make any edits to other art in your file.

Between the two thumbnails, there is a link icon (on by default). When the art and the mask are linked, they will be transformed together. So if you move the art, the mask will move with it as well (so that the appearance will be the same). You can click on the link icon to disable the link, at which time you can move the mask and the art independently.

The Clip option uses the shape of the mask to also clip the art under it (basically giving the same effect as a clipping mask in addition to the opacity levels).

The Invert Mask option enables you to reverse the luminosity values of the mask object. In simple terms, when you toggle this option, anything that was previously visible through the mask becomes hidden, and everything that was hidden becomes visible.

An object with an opacity mask applied to it is indicated in the Layers panel with a dashed underline. To release an opacity mask, select the masked object and choose Release Opacity Mask from the Transparency panel flyout menu.

Illustrator has five basic transformation functions: Move, Rotate, Scale, Reflect, and Shear. Illustrator also has a Free Transform tool and a feature called Transform Each that enables you to apply transformations to multiple objects with one click. You can also use the Transform panel, which makes for quick and precise transformations. I know it sounds confusing, but hang in there because this will all be second nature before you know it.

Before we talk about transformations, I want to point out one particular keyboard shortcut that is a real time saver. Holding down the (Cmd) [Ctrl] key at any time activates the most recent arrow selection tool you’ve used. For example, if you last used the Selection tool, pressing this keyboard shortcut while using any of Illustrator’s other tools temporarily activates the Selection tool. If the Direct Select or Group Select tool is active, you get the Selection tool; if the Selection tool is active, you get the Direct Selection tool.

When it comes to transformations specifically, you are always selecting objects and making minor changes to the art. Having to switch back and forth between the transformation tools and the selection tools is a pain. With the (Cmd) [Ctrl] key, the Selection tool is always just a keystroke away.

Although not necessarily a transformation, in that the actual object is changed, moving an object is considered a transformation because the coordinates of the object are being changed (we talk more about coordinates shortly, when we discuss the Transform panel).

You already learned one way to move an object: by clicking and dragging a selection. Illustrator also lets you move things more precisely. If you click and drag a selection and then hold down the Shift key, you can drag your selection only along a constrained axis in increments of ![]() .

.

Want to get even more precise? After you make a selection, you can use your keyboard’s arrow keys (up, down, left, and right) to “nudge” your selection incrementally. You can control how much each nudge is in the General Preferences panel by pressing (Cmd-K) [Ctrl+K] and changing the keyboard increment (see Figure 7.90).

Still not precise enough for you? If you want to move objects numerically, make your selection and then double-click on the Selection tool in the toolbox (the black arrow). In the resulting dialog box, seen in Figure 7.91, you can specify an exact amount to four decimal places. Entering negative numbers moves the object down or to the left. In this dialog box, you can also choose to move a copy of your object—and there’s a Preview button that enables you to view the results of the move before clicking OK.

There’s yet another way to move something: Illustrator’s Transform panel, which we’ll get to soon.

The four transformation tools—Rotate, Scale, Reflect, and Shear—are very similar. As you should know by now, before making any transformations, you must first make a selection.

With Illustrator’s default setting, when you make a selection, the object is highlighted with a rectangular shape that has hollow squares at the corners and the centers of each line (see Figure 7.92). This is called the bounding box, and it enables you to make certain transformations to the selection without having to select a different tool.

Clicking and dragging on any of the hollow squares enables you to scale the selection in that direction. Pressing the Shift key while dragging one of the hollow squares constrains the proportions of your selection. Pressing the (Option) [Alt] key when dragging scales the selection from its center.

If you position your cursor just outside any of the corner hollow squares, you’ll notice that your cursor changes from a straight arrow to a bent arrow. If you click and drag outside the object while the bent-arrow cursor is showing, you can rotate your selection around its center (see Figure 7.93). Pressing the Shift key while dragging constrains your rotations to increments of ![]() .

.

I’m not a big fan of the bounding box myself. For one, it was added to Illustrator a few versions back to appeal to users who had used other illustration tools, such as CorelDRAW, that featured this kind of functionality. Second, as you’re about to find out, there are specific scale and rotate tools in Illustrator that offer more powerful options. Finally—and most important, in my opinion—you can’t perform certain transformations when the bounding box is turned on. For example, say you want to drag an object by its corner to move it (I’ll explain in a moment why you would want to do that). With the bounding box turned on, if you drag from a corner, the object will scale rather than move. Illustrator has a snap-to-point feature that enables you to easily align objects as you position them. So you might want to grab a rectangle by its corner and move it to the edge of the page where the corner would snap to the edge of the page, making it easy to move objects with precision.

Anyway, I digress. The bottom line is that you’re now going to learn the most powerful way to perform scale, rotate, reflect, and shear transformations in Illustrator. The bounding box was really created for anyone who doesn’t plan to read this book. Although you can certainly keep the bounding box option turned on when using the other transformation tools, I’m going to suggest that you turn it off for now because it will be easier to learn the new tools that way. You can toggle the bounding box by pressing (Cmd-Shift-B) [Ctrl+Shift+B].

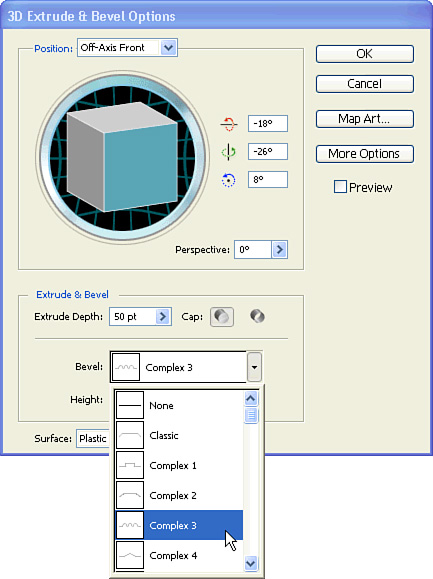

To apply a rotation, make a selection and press the R key on your keyboard. Right away, you’ll notice a new icon in the center of your selection, which is called your origin point. The origin point is the place from where your transformation begins. As you’ll soon see, all the transformation tools use an origin point, but specifically with the Rotation tool, your origin point dictates the center of your rotation.