In This Chapter

Understanding inputs and outputs

Using assets and tools to deliver services

Looking at a standardized process model

Providing flexibility with skilled participants

Overseeing the service

In this chapter, we introduce a very simple model of a service, looking at it from the inside. By providing some examples and figures, we help you understand how just about everything around you can be viewed as a service or a component of a service. To create a strategy for service management, you need to start by understanding some basic principles of service delivery and management. This chapter provides this basic level of information about managing services. To keep things simple, we ignore the fact that every service has a consumer and consider just what makes up a service from the inside.

Note

Keep in mind one simple but important principle: The customer doesn't really want to know what makes the service tick. He wants a service that provides a valuable result or outcome.

In Chapter 1, we stake a huge claim and say that everything is a service. Although we're a little cavalier in defining the term that way, we don't have much choice, because what we're really doing is focusing on every activity to which you can apply service management, such as delivering food in a restaurant, responding to customer service queries, or producing manufactured goods.

Note

Think of every activity within a commercial organization as being a service or a component of a service.

We define service this way:

A service is a purposeful activity carried out for the benefit of a known target.

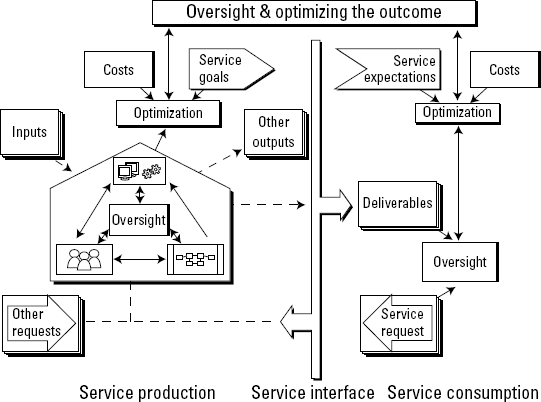

In this chapter, we're interested primarily in the first half of that definition: A service is a purposeful activity. We focus on what a service looks like from the inside, as shown in the diagram in Figure 2-1.

As Figure 2-1 indicates, a service has inputs and outputs. The input is a request for the service− something that triggers the activity. The output of a service is an outcome. The outputs of a service provider can include both products and service outcomes, which can be anything from a product (an Apple iPod) to an outcome (a mowed lawn) to a product and service outcome (a meal and restaurant service). The internal activity of the service transforms the inputs into the outcomes. It typically involves people, whom we refer to in Figure 2-1 as skilled participants. It involves the assets and tools (which can be as simple as a pen and paper or as complex as a manufacturing plant) that are used to execute the service. The service also involves a standardized process model — a method for delivering the service. This process may be so simple that the skilled participants can pick it up in a few hours, or it may be complex, consisting of sets of rules that shape systems and determine how a whole department within an organization carries out its work.

The services that we're most interested in are the activities carried out by large organizations.

Note

Services are often made up of a group of component services, some of which may also have component services.

You can think of an accounting department, for example, as providing a service to other departments, to the executive board, and also to the shareholders. You can consider what an accounting department does as a single service, and from the auditing perspective, you probably should. But you can also consider an accounting department to be a collection of services because it contains multiple distinct activities: accounts receivable, general ledger, and so on. You can view each activity as being a component service.

The delivery of a service usually involves a request that initiates the delivery of the service and the processing of a set of inputs that delivers the desired outputs. Figure 2-2, which looks extremely simple but masks a fair amount of complexity, illustrates this process.

Services of all kinds can be very immersive(meaning that you become part of the process) or not particularly immersive (meaning that the process happens without your interaction). Visiting an automated teller machine (ATM) to get money, for example, isn't particularly immersive because the customer activity is very simple. The customer requests the service by inserting her card into the ATM. The only other inputs that the customer provides are a personal identification number (PIN), entered for the sake of security, and information about the amount of money required. The ATM checks to see whether the customer is entitled to withdraw money and delivers the money with a receipt.

The whole transaction probably takes less than a minute, and the customer isn't exposed to any of the complexities that make such a service possible. The service is simple, and it works as long as the customer performs the customer activities and the provider performs the provider activities under an agreed-to set of rules.

Now contrast this example with being taken to a hospital with appendicitis, having an appendectomy, and then recovering in a hospital room. Clearly, this service is highly immersive, and the customer is thoroughly exposed to a great deal of the activity that delivers the service. In this example, the customer for the service is also one of the inputs to the service. The same is true of other services, such as providing training to a group of people to increase their skills in some way.

Note

Services, as we define them, always transform something, and they complete by delivering an output, whether that output is cash from your bank account or relief from appendicitis.

You may wonder why we choose to use the symbol of a building to contain the elements of a service in Figure 2-1 and Figure 2-2, earlier in this chapter. Our intention is to provide an impression of a space in which a service is carried out. Every service is carried out somewhere, perhaps in a collection of places, and it may even be distributed around the world via a process involving many call centers and computers.

You use essentially three types of assets and tools to deliver a service:

Work environments (buildings)

Mechanical tools (vehicles)

Digital tools (computers and communications devices)

What assets and tools have in common is that they all cost money and need to be maintained − and possibly replaced − over time. Digital tools are devoted primarily to collecting and managing information, whereas mechanical tools are related primarily to manipulating or moving things, and the environment is the space within which the activity takes place.

If you think of a very complex service, such as providing a passenger flight from one place to another, you see that the assets and tools are highly diverse, involving airports (including hangars and runways) as well as call centers and offices in many places. The associated machinery is complicated, too, given the engineering and logistical support that an airplane needs. The computer and communications systems also are complex.

Neither could we claim that our example of an ATM service is simple in this respect. The service is simple enough at the interface − the card goes in and the money comes out − but as we show in Chapter 1, an array of complex information technology (IT) systems is involved in making the service happen.

Every process, from tying your shoelaces to sending astronauts to the moon, involves an activity-based workflow. Processes are sometimes newly invented. Gold-medal Olympian Dick Fosbury, for example, invented the Fosbury Flop, an original technique for executing the high jump that changed the way that the event is executed today. Most of the time, though, the elements that compose processes evolve, improving to some degree over time.

Even the simplest of services has to be managed as a process. The process flow may be stated explicitly and documented somewhere, or it may not be. It may influence the way that assets and tools are deployed, or it may not. It may demand that staff members be trained to understand how it works, or the process may be obvious. All these factors can vary.

Figure 2-3 depicts the process model as a flow diagram, representing the proper activity for taking the inputs of a service and transforming them into desired outcomes.

We can describe the ATM cash withdrawal service in a standardized process model by showing the input (the ATM user inserts the card and enters the requested information), the process (the ATM verifies the PIN against encoded information on the card and checks the amount of money requested against data in the user's bank account), and the output (the ATM dispatches money).

If we include all the surrounding management activities that support the service, however, the process model is more complicated. In this case, the model has to include the activities of various support systems throughout the bank's network, such as check depositing and check clearing, as well as the scheduling of security personnel to deliver money to the ATM at various times as the machine begins to run short.

The more complicated model shows that some of the activities are actually defined as computer programs that automate part of the service (such as the process that debits the money from the ATM user's account). The whole process is built and automated to work with very little intervention from human beings, and the part of the process model that describes what human beings have to do is very simple.

After you clearly define a service, you have to work through how you'll manage that service. The process model describes how the service is delivered. Service management describes how you'll manage the service, addressing such questions as these:

How will you keep track of the configuration of the service?

How will you manage changes to the service?

How will you manage incidents that may occur?

How will you monitor the service?

How will you manage requests related to the service?

Note

For all repeated services, a process is employed to carry out the service, and a set of service management processes is used to manage the service.

The most flexible part of most services is the staff. To carry out their work, the members of the staff must have the following traits:

Good judgment

Intelligence

Proper skills

Knowledge of their roles

Flexibility

The activity of automating service of any kind involves automating the predictable and repeating elements of it, leaving the exceptional cases to the people who are involved.

In most services of any size, the staff members who deliver the service have specific roles that involve them in specific activities. In many instances, they need to be trained in specific skills, and they were hired because they have the requisite intelligence and judgment.

In many circumstances, although a standardized process is in place, it's almost wholly enshrined in the knowledge of the person who's carrying out the task. In fact, many services have two information systems: the computer system and the skilled staff members who deliver the service.

We think of the oversight system (or service management system) as recording all the information about the service or any aspect of the service that can be useful in any way. Thus, the oversight system may refer to the standardized process model to gather measurements about the speed of any given activity or the speed of flow from one activity to another. It may take readings from sensors embedded in machinery or from programs that monitor the activity of computer systems, and it may take information directly from the skilled participants who carry out the service.

This book is about service management, but our model of a service currently includes nothing that relates to managing the service. We address that problem in Figure 2-4 by adding the element of oversight.

As far as oversight is concerned, you shouldn't think simply in terms of computer systems gathering and analyzing information. You also need to include physical systems, such as the fire-alarm system that's deployed throughout the working space, the central heating system, or even a nuclear power plant.

The point is that for most services, many individual oversight systems operate within the overall service management system, contributing to the proper performance of the service, but you should have most interest in the oversight systems that provide feedback to those who carry out the service. Oversight systems that provide feedback on how efficiently the service is running are especially useful to the people or computers that carry out the service. Their primary role is to ensure that the service is delivered at a level that is acceptable to the service user.

Take a moment to review Figure 2-1, earlier in this chapter. In this section, we discuss that figure from the service management point of view.

The first thing to note is that service management doesn't concern itself only with what we think of traditionally as computer and communications systems. Information technology is now embedded inside most assets that in the past may not have been thought of as IT assets. In fact, an increasingly blurry line divides enterprise physical assets(such as buildings, furniture, landline phones, and security systems) and IT assets(servers, laptops, and mobile devices) as all assets become increasingly smart, interconnected, and instrumented by design.

Although many of us think about managing computers and communications systems, this example is only the tip of the iceberg. Service management really looks to manage physical environments (plants, facilities, trucks, and so on) as well as IT systems, and it defines processes, functions, and roles for people. In our ATM example, we aren't talking just about IT technology. The ATM service also relies on trucks, the people who replenish the cash, and the paper on which receipts are printed.

When you examine the mission-critical activities of your organization, you usually discover that computer systems play a central role. As far as this discovery is concerned, we have good news and bad news:

Luckily, businesses have been using IT (including computers, applications, networks, storage devices, and security firewalls) for decades, and in doing so, they've accumulated a mass of experience and a wealth of assets. The experience that businesses have accumulated spans all these areas; more important, more physical assets are transforming into IT assets with the inclusion of smart chips and sensors that allow them to be managed as IT assets. An explosion of computerization or smartening of dumb assets is occurring, allowing service management to control the broad set of assets more easily and adding complexity to what were once simple applications, systems, and networks.

The service management experience is embodied to a great extent in the hundreds of thousands of computer professionals who run the systems. The assets include a wide range of software that's purpose-built to assist in service management. Much of this software has evolved over many years. In addition, we have standardized process models and best practices for service management, such as the Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL), the enhanced Telecom Operations Map (eTOM), and Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology (COBIT). (For more information, see Chapter 4.) Any organization that needs to consider implementing or changing the way that it manages the services it delivers can leverage these resources to augment its service management planning.

In this chapter, we consider only the internal operation of a service. A service has inputs and outcomes, involves the use of tools and assets in a specific environment, and is carried out by skilled participants who implement a standardized process model, and the whole environment is subject to the oversight of the service management system.

What we haven't done is discuss the nature of that oversight and what it involves in detail, but you've probably deduced that it involves service management. The notions of both service and service management are critical. The staff members who deliver a service take pride in their activities and also seek to improve their efficiency so as to make the service better over time. In addition to the delivery of the service, many activities are required to manage the service. You need to consider the following questions:

How will you plan and manage changes to the service?

How will you monitor service levels and service costs?

How will you manage incidents that may occur?

How will you manage the availability and continuity of the service in the event of a major unplanned disruption?

How will you manage the security of information within the service?

How will you direct, evaluate, and monitor compliance with required regulations or polices?

How will you manage exceptions?

Service management needs to be effective to answer these questions, but in the end, the execution of the service itself must be done in such a way that the customer finds the outcomes to be valuable, convenient, and correctly priced.