In This Chapter

Figuring out what the target and customer want

Viewing a service from the outside

Delving into service management

Using services as components of other services

We look at a service from the inside in Chapter 2, so it seems logical that in this chapter, we take a look at a service from the outside. In Chapter 2, we focus on the first part of the definition of a service (a service is a purposeful activity); in this chapter, we focus on the second part (carried out for the benefit of a known target).

We could say for the benefit of the customer, but we don't. In most circumstances, satisfying the customer isn't the only driver that shapes a service. If the service is delivered by a public company, for example, you also need to satisfy the shareholders. You can quite easily make the customers happy and still go out of business, and the shareholders are unlikely to approve such a business strategy. So in addition to executing the activities of a well-defined service in a high-quality manner, service management needs to include both a customer satisfaction process and a stakeholder-requirements management process to ensure that the needs of all stakeholders are known and managed.

So when we say for the benefit of a known target, we may be talking about a need to satisfy multiple targets, each of which has a specific expectation of the service. The shareholders care about profitability, whereas the customers care about the quality of service.

The most important thing to understand about customer expectations is that they're defined by context. If you want to deliver an appropriate service, you need to satisfy the expectations of the customer. Like most people, you've probably been to expensive restaurants and also to fast-food joints, for example. Although you were the same person in both types of restaurants, you definitely weren't the same customer. At an expensive restaurant, you expected excellent service, an intriguing menu, a wine list, a pleasant environment, and so on. At a fast-food joint, you expected swift service and predictable food.

As customers, people are defined by their expectations. Thus, if you want to deliver an appropriate service, you need to satisfy the customers' expectations.

Consider an automated teller machine (ATM) transaction. ATM customers' expectations are very easy to define. Customers expect the ATM to work properly, dispense money in a reasonable amount of time, and keep their financial data secure. Customers don't really care how an ATM accomplishes these tasks as long as it works the way they expect it to. As far as they're concerned, the ATM can involve a vast integrated computer and communications system, or someone could be hiding inside the machine with a wad of bills, pushing them out of the slot when requested. Both systems are the same as far as the customer is concerned; how the service is achieved is irrelevant.

Another important aspect is selection. Customers either select a service or have no choice. A person entering the United States through an airport, for example, is stopped by the U.S. Customs Service. The customer in this instance can't say, "I don't think I like this customs service; I'll use Canada's instead." The fact that the U.S. Customs Service has a monopoly at all U.S. borders, however, doesn't prevent it from wanting to provide unobtrusive service to innocent travelers while preventing banned substances and smugglers from entering the country.

Note

The expectations of the customer are defined primarily by context.

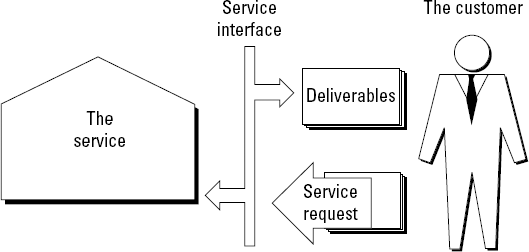

The customer of a service sees only the external view of the service interface, as shown in Figure 3-1.

Although the service may have many inputs and outputs, the customer is directly aware of only the outcomes provided directly by the service and the inputs (such as a security code) she provided, along with the service request (such as the amount of money she wants to withdraw).

Suppose that you take your shoes to a cobbler and tell him what's wrong with them. Later, you collect the shoes, and you judge the level of service primarily by whether the cobbler mended the shoes effectively.

In this situation, the cobbler managing the service probably focuses on the quality of workmanship and the time taken to complete the work. Unless he measures factors such as customer satisfaction, transaction trends, pricing trends, and margin trends, however, he'll have no idea whether he's delivering the appropriate service level based on both customer and stakeholder requirements.

Note

In evaluating service quality, measurements of customers' and stakeholders' satisfaction are the most important.

If the cobbler pays special attention only to the quality of the work, he may be investing in the wrong thing. Perhaps he has a good location filled with wealthy customers and no nearby competitors, so he may be able to spend more time on repairs and charge more without driving away customers. If his method of providing service is sustainable, he needs to gather information from his customers. If he's going to be successful, he needs to discover the key factors that will satisfy his customers. On the other hand, if the cobbler measures only the customer experience and fails to track progress on stakeholder requirements, he may go out of business. He may spend so much time or charge so much for each shoe repair that his customers would have been better off buying new shoes.

The management of a service to ensure that it meets the critical outcomes the customer values and the stakeholders want to provide.

Before we go any further, we need to distinguish between the execution of a service and service management. The execution of a service is the process of performing the task, whereas service management is the process of making sure that the task is performed according to expectations.

An ATM is a good example of a service because the service outcomes desired by the customer and stakeholders are simple and not subject to debate. The customer wants quick, accurate, secure, affordable, and always-available service transactions, and the stakeholders want seamless delivery of the service at an affordable price with the right level of oversight.

Those features are all that the customer −we'll call her Jane −expects, but her expectations actually are high. Jane expects the ATM to be available 24/7, to be free of errors, and to be fast. If she turns up at an ATM at 4 a.m. and the ATM isn't working, she's much more likely to get annoyed and curse the bank than to think, "After all, it's 4 a.m. Perhaps I was optimistic in expecting to get money at this time of day."

As far as ATM service is concerned, the critical customer service needs are well understood. Ever since ATMs were introduced, customers have had high service expectations, and because banks can save money and even generate revenue by deploying ATMs, financial institutions are willing to make the investment to deliver the quality of service that customers demand.

In fact, the ATM service was highly automated from the get-go, and even at the outset, the level of automation was such that the service was delivered primarily by purpose-built computers and communications technology.

The assets and tools that are involved in providing the ATM service include the ATM devices, the secure communications links from the ATM to the bank's data centers, the applications that manage customer checking accounts, the systems that manage cash distribution, the bank's customer support center, and the processes for recording lost or stolen cards. (For more information on how assets and tools fit into the service management model, refer to Chapter 2.)

The service management systems monitor the ATM's service systems to prevent those systems from failing and affecting customers' service expectations. A system isn't necessarily made up only of technology. A typical system, in fact, is made up of people, processes, technologies, and information. In addition to the service management system, service providers need good governance to minimize performance declines during periods of change and innovation.

Note

Service management systems are the systems that support the systems that deliver the service.

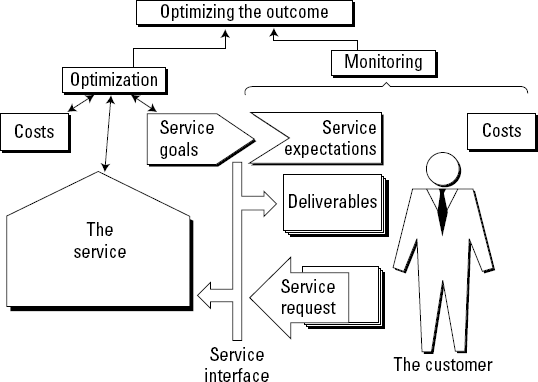

To keep customers satisfied, you need to identify key service performance indicators as well as key goal indicators −and monitor them closely so that you meet both customers' and stakeholders' expectations, as illustrated in Figure 3-2.

The important point is that in most situations, clear commercial constraints apply. The service provider has costs, and as the service level delivered increases, so do the costs of delivering the service. The role of the key service performance indicators is to set the acceptable service level so that the level of customer satisfaction is high. Then you can optimize the delivery of the service so that you deliver the highest service level at the lowest cost.

You mustn't lose sight of the customer, however. The customer also has costs (the price he pays for the service) and service expectations. Because we live in a competitive world, the customer's service expectation probably won't always be the same. Most likely, the customer will expect to get more for his money as time passes.

To optimize your outcome over time, you need to monitor customers' expectations on an ongoing basis; simply assuming that current service goals will remain static isn't good enough. The situation is dynamic, and when customers' expectations change, the service provider needs to recognize and respond to the changes.

To achieve this goal, measure both performance and desired outcomes. You can measure customers' expectations by conducting customer feedback surveys and by monitoring customer responses to changes in price or other factors that affect the delivery of services. Companies use a variety of traditional surveys and Web-based monitoring tools to measure sales and customer relationship effectiveness and to keep track of performance at many levels. You must measure service activities for aspects such as cost, duration, human effort, and quality. You also need to measure progress toward the outcomes that both the customer and the stakeholders had in mind when the service was established.

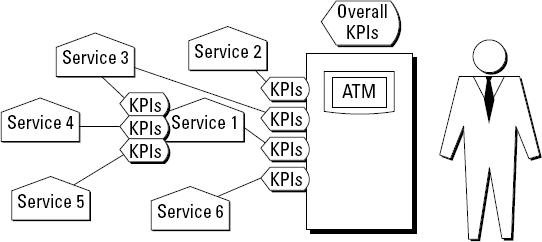

If you want to optimize a service, you have to optimize the whole service rather than each individual service component. In the ATM example, there's little point in ensuring that the ATM is always well stocked with money if the system that provides information about the customers' bank balances fails. You have to optimize the ensemble of services holistically.

The activities that deliver a service usually can be broken into multiple other activities. You can consider each of these component services to be a service in its own right, in which case it also has a customer. The customer for each component service isn't the ultimate customer of the whole service, however, but simply the receiver of its outputs.

This relationship gets very complicated. If you consider an ATM service, you can envisage a whole set of coordinated component services, such as the marketing of certificates of deposit (CDs) and the provision of insurance forms. Suppose that the marketing department of ABC Financial has added some new screens to the ATM and that each screen is backed by a new component service. The two component services −marketing CDs and providing insurance forms −are actual services that a human teller might provide, and the ATM has been programmed to provide a form of these services as well. The consumer receives the outputs and benefits by getting answers to questions immediately rather than waiting to speak with a teller.

The same is true for service providers and consumers. Customers have customers who have customers. Suppliers have suppliers who have suppliers. The extent of the service management system almost reverberates into eternity. Individual people both give and receive service all day long, and it's human nature to worry about the part of the service management system that you control. In today's complex world, however, you also need to care about the connections among services and the dependencies among services. In other words, if your supplier takes a risk, it's your risk too.

Consider the activity or service of delivering cash to the ATM. The ATM has a defined service to dispense cash. A key performance indicator (KPI) for this service component includes delivery of the right amount of cash within an acceptable time frame. This activity is only a piece of the whole picture, however; additional services fill out the full set of activities. The security of the transaction, for example, is imperative to the ATM service as a whole, and the security service has its own set of KPIs. Therefore, the entire ATM service to customers incorporates a whole set of KPIs, as illustrated in Figure 3-3. This situation is true for all other component services. Consequently, if the KPIs for the whole service change, you also need to adjust the component KPIs.

Note

To optimize a service, you have to optimize the whole service across all interdependent component services. Optimizing select components out of context isn't enough.