Chapter 1

Evolving and Holistic View of Service

1.1 What is Service?

The word “service” has many connotations, varying with domains and settings. We must understand and deal with its extant variability in order to decipher and capture its inherent nature in business (Morris and Johnston, (1987). This is particularly important for this book because we have to stay in focus to discuss one solution, namely our unique and innovative approach to address the challenges that we have faced in the service sector over the years or new challenges that we will confront for the years to come. Put in a straightforward manner, presenting the “BEST” solution to address all the challenges confronted by academics and practitioners in the service sector is surely not our intention as there will never be such a one-size-fits-all solution. Given that the business world becomes more integrated, complex, and interdependent than ever before, a systemic view of service is the mindset that we will hold throughout this book. In other words, by relying on systems thinking and holistic viewpoints (Flood and Carson, (1993), we will explore and accordingly decipher the inherent nature of service in the unceasingly changing business world.

Service is frequently defined as an act of beneficial activity. A service that is considered as an act of beneficial activity actually has a long history. If we retrospect to the simplest material exchange that occurred in ancient times, such as a bushel of wheat exchanged for a barrel of oil, we know that a very basic trading service was performed. No matter what units and containers were used and how the trade was done in ancient times, the exchange or trade, a performed service, was essentially an act of helpful and beneficial activity that met the respective needs of the involved exchangers.

A food service in a restaurant is another good example of an act of beneficial activity. Similar to the above-mentioned simple trading service, we can also easily retrospect to ancient times in the early social and economic development stage thousands of years ago. A food service in ancient times certainly had no conceptual difference from a modern food service. Although the catering setting and foods in a restaurant at that time were limited and simple, a performed service was substantively involved with a list of necessary service elements, provider, consumer, resource, process, and value. The service provider was the owner who owned the restaurant and offered dishes as service products. A service consumer was a client who ordered and ate his or her selected foods. A typical service process started from the time the client entered the restaurant and ended when the client paid for the service and left the restaurant. The process was involved with a transformation with the support of operation resources. The client's order is the process's input. The value for the client and the owner is the process's output. The value could simply be the profit the owner made and the satisfaction the client had. The client's hunger stopped; he/she was happy to some degree. Surely, the service was mutually beneficial. Resources, largely natural and labor-based, were leveraged in an extremely simple manner throughout the simple catering process (Figure 1.1). Without question, the corresponding business operations at that time were radically experience-based.

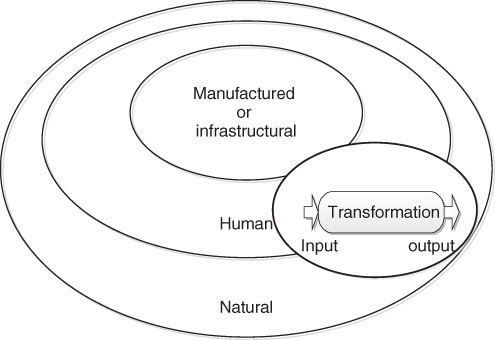

Figure 1.1 A conventional resource model view of a food service.

Figure 1.2 A service involving certain fundamental elements.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the conventional classification of resources. By focusing on resource supply and demand in the social and economic activities, we understand how resources are leveraged in the transformation of goods and services to meet human needs and desires. As a result, we traditionally recognize three categories of resources: natural, human, and manufactured or infrastructural resources. Natural resources essentially are the source of raw materials. Human resources consist of human efforts provided in the transformation of products or services. Manufactured or infrastructural resources consists of man-made goods or means of production (machinery, buildings, and other infrastructure) used in the transformation of other goods and services (Samuelson and Nordhaus, (2009); Sullivan et al., (2011).

Regardless of what type of service is provided and consumed, five essential and core elements characterize a service in a conventional act of helpful and beneficial activity (Figure 1.2). More specifically, the five elements involved in services are resource, provider, consumer, benefit, and time, which can be described in an intuitive way as follows:

- Resource. Resources can be in a physical, soft, or hybrid form. For example, foods as a physical, transformable, and consumable resource or service product in a restaurant play a fundamental role in a given food service. Knowledge or experience in a focused subject area transferred in a training service seems to be a soft resource or service product. When a haircut service is performed, both barber's skills and haircut kits as a hybrid resource must be simultaneously applied or operated to make the service performed in a satisfactory manner. Essentially, with the help of resources, the act of performing a transformation task for a customer who asks for it in exchange for acceptable compensation is termed as service provision. Apparently, resources are the radical conduits of service provision to customers (Vargo and Lusch, (2004).

- Provider. A service is purposely performed by a service provider. A service provider as an entity can be an individual, group, organization, institution, system, or governmental agency.

- Consumer. A service consumer is usually a human being who consumes, acquires, or utilizes a service offered and performed by a service provider.

- Benefits. A performed service surely generates certain benefits. Typically, different benefits are pursued by the service provider and the service consumer as they have different value propositions in executing the service. The benefit for the service provider could be value-based, such as a profit. The benefit for the service consumer might be need-based, such as desire and satisfaction.

- Time. Small or big, simple or complex, a service certainly takes time to get performed to realize the desired benefits. Interactive activities between the provider and the consumer could occur in an ad hoc or predefined, unattended, and/or well-controlled process.

Note that service provider-side employees and customer-side consumers should also be part of recourses if we strictly follow the resource model as is illustrated in Figure 1.1. To make the discussion vivid and people-centric, we have to emphasize the identity of active participants in the service model that will be developed and discussed throughout this book. Therefore, we will always make an exception from the general resource model by distinguishing the elements of providers and consumers or customers from the general human resource concept. The concept of human resource in Figure 1.1 will be needed only when the whole resource model is the focus in a related and focused discussion.

Indeed, no matter how small or big, simple or complex a service is, it surely takes time for its provider to perform and its customer to consume the service. Evidently, the consumer and the provider of the service shall interact with each other, directly or indirectly, consecutively or intermittently, physically or virtually, and briefly or intensively, during the process of performing the service. The interaction time accordingly can be short or long. All of these changing factors that largely characterize provider–consumer interactions vary with the types of services that are actually performed. Hence, there are a variety of perspectives on service in academia and practice.

1.2 Different Perspectives on Service

Because of the existence of the above-mentioned variations in perception, a consumer's perception of one kind of service could differ considerably from another. Different forms of resources applied and operated in executing services and varieties of provider–consumer interactions create many different combinations of consumers' perceptions of services, which consequently complicate our service studies in academia and practice. Different consumers' perceptions of services then give rise to the existence of numerous definitions of service. As a result, different service industries have historically adopted different definitions of services to accommodate their respective needs. For example, service is also quite often defined as the supplying of utilities or commodities in the modern economic society. From an end user's point of view, consuming electricity as a service fits in this definition very well. If we consider the daily consumption of electricity as an example, we will see that there is very little interaction between its provider and customer. Typically, we as home owners or apartment tenants in the United States simply call a local office of an electricity service provider we choose, and then we inform the electricity service provider of the date we move in. When we move out, we simply do the same. The needed simple interaction serves only one purpose, which is basically to ensure that the monthly bill statement will accurately and correctly reflect the usages of electricity when we legitimately stay in the houses or apartments. Unless there could be a problem with power lines or a discrepancy in a monthly bill statement, we might not interact with the electricity service provider at all during our entire stay in the house or apartment. We as consumers feel that there is a very little interaction with a service provider; such a service is undoubtedly defined as the supplying of utilities from an end user's perspective.

The unceasingly increased online shopping in the twenty-first century presents another perfect example for a service that is defined as the supplying of commodities. It is well understood in the retailing industry that this supplying of commodities as a service includes commodities, related distributions, and retailing. However, to an end user, such an online shopping service is nothing but the supplying of the needed commodities. We as online shopping customers place orders from a website powered by an online retailer (i.e., a service provider). The orders will be delivered to us regardless of how the orders are fulfilled and how far away the orders have to be transported. Just like utilizing electricity at home, unless there would be a problem with the ordered commodities, we might not interact with the online retailer after the initial online order placement. Obviously, there is surely little physical interaction between a service provider and a service customer throughout the lifecycle of such a typical online shopping service.

Other forms of definitions of service include the providing of accommodation and activities required by the public or the supplying of public communication and transportation. A variety of services in the modern economic society fit in this category of service definition. A list of good examples will be trading, communication, transportation, tourism, hospitality, and health care services. Nevertheless, services provided by educational institutions, security and military, and governmental agencies can also be well classified in this category of definition.

As mentioned earlier, different consumers' perceptions of services have historically resulted in the existence of numerous definitions of service. At first glance, different forms of definitions of service seem to define different things. When we further examine these definitions, it is not difficult for us to find that regardless of how a service is defined in a given discipline in academia or in a specific service sector in practice, a service must include the five core elements shown in Figure 1.2. The differences felt or perceived by customers based on their perceptions of services come from user's experiences (Qiu, (2013) acquired from service encounters by the customers throughout the lifecycle of service executions.

Figure 1.3 The lifecycle of service: a classic service diamond.

1.3 The Lifecycle of Service

In both academia and practice, we can find many versions of defined phases that compose the lifecycle of service. Depending on what we expect for a service or largely perceive during the process of consuming a given service, we might use different constituting stages to compose a service lifecycle. Quite often, we are subjectively or objectively impressed by certain phases or stages of the lifecycle of service. Then, we tend to ignore other phases that we prejudicially think they are less important. The information technology infrastructure library (ITIL®) version 3 (ITIL, (2011) is a nonproprietary and publicly available set of best practices for information technology (IT) service management. ITIL v3 defines five phases of service lifecycle, service strategy, design, transition, operation, and continual service improvement, and accordingly provides comprehensive guidelines throughout all the phases for aligning IT services with the needs of business. We also frequently derive the definitions from the ones widely applied in the manufacturing sector. As a result, just like service, a variety of terms or definitions of the lifecycle of service exist.

Regardless of how many versions we can find in the extant literature, all the described lifecycles of services should always be composed of four essential and classic phases, “learn,” “develop,” “perform,” and “improve,” from a service provider point of view. We use these four essential and sequential phases in a service lifecycle to define the fundamental service diamond relationship in a service organization, which are illustrated in Figure 1.3. These four phases are briefly discussed as follows:

- Learn. We have to know what the market need is before the concept of a new service product gets conceived. Regardless of the type of service, we have to learn the market to identify the needs of prospective customers through a variety of approaches. We understand that customer needs keep changing as time goes. Therefore, we have to learn and capture the changes and accordingly incorporate the changes into service provision throughout the lifecycle of services.

- Develop. We develop, transform, or leverage resources to serve customers and meet their needs. Frequently, the resources in service are mainly and paradoxically perceived as service products. Indeed, as we discussed earlier, the resources in the service industry can be in a physical, soft, or hybrid form. Leveraging all natural, human, and infrastructure resources are essential in service provision. The operand or operant roles of resources in rendering services are significantly more sophisticated than the ones in the manufacturing industry. As a matter of fact, operant resources in service provision produce the effects that are largely perceived and truly appreciated by customers (Vargo and Lusch, (2004).

- Perform. This phase is largely highlighted by a process of service provision. Typically, the performing phase in a service lifecycle is known as the delivery of the service. For a service designated to a given customer, this is also the phase that the majority of service encounters occur from the customer's perspective.

- Improve. As we know that customer needs keep changing as time goes, we must continuously improve our services to stay cutting-edge in the business. Indeed, the improvements in all aspects of services are crucial to keep our services competitive (Qiu, (2013).

This classic service diamond relationship in a service organization clearly marks the four key milestones across the lifecycle of service. When the first version of services is conceived, developed, and offered by a service organization, clear and well-specified milestones that are explicitly based on the above-defined sequence might be created and followed from the operations and management perspectives. During each phase, the service organization usually has different business objectives set as the highest priority in management and operations. The diagram in Figure 1.4 shows a normal and classic view of managerial and operational priorities pursued in the service operations and management of a service firm, in which a milestone priority shifts along with the emergence of a new phase during service business operations. These typical four priorities that are logically identified throughout the lifecycle of service are briefly discussed as follows:

- Innovation. A service is not competitive unless it is creative and innovative. Service products are just part of a service. First of all, we should focus on the transformation of resources to innovate services that are aimed at positioning our services in the market for competitive advantage. Innovations must be thoroughly embodied in not only the service products, but the processes of delivering and improving the services.

- Value Proposition. The execution of a service by a service provider must create a value for the service provider. As a service takes time from beginning to end, we must have the value of a service clearly defined in order to have the value appropriately measured, monitored, and realized in the process of service provision.

- Value Creation. The targeted value is usually created in the process of service delivery. However, it is not uncommon in the service industry that we argue that the delivery of a service actually starts from its development phase.

- Performance. We know how a service meets the needs of its end user once the service is delivered. Quite often, we would like to have the deliveries to be monitored, so the real-time performance of our service businesses can be captured and then weakness can be identified for further improvements.

Figure 1.4 Priority shifts in service business operations and management.

Similar to the lifecycle of manufactured goods, the relationships defined in Figure 1.4 are most likely neither strictly linear nor purely sequential. In other words, the four priorities should not be separately considered during business operations in a competitive service organization. Frequently, a service organization will operate all the four phases in parallel as soon as the first batch of services gets completed. Please keep in mind, the first batch of services could simply be prototype or trial-based services. Competitive services are the results of both the coordinated and collaborated business actions taken by all the employees in the service provider, resulting in that satisfactory consumptions are realized and thus quality services are perceived by the customers.

1.4 Service Encounters Throughout the Lifecycle of Service

Before the emergence of the Internet, a physical context type of interactions between a service provider and a service customer was radically necessary in the process of performing a service. We define a service encounter as an act where a customer interacts with the service the customer wants. Therefore, a service encounter essentially is a social and transactional interaction in which a service provider performs a service activity beneficial to its corresponding service customer (Czepiel et al., (1985); Czepiel, (1990); Bitner, (1992). Undoubtedly, each service encounter becomes a moment of truth. For a given service, we are the service provider and might perform “good” or “bad” services by rendering “good” or “bad” user/service experience. In other words, we have the ability to either satisfy or dissatisfy a customer when we are engaged in a service encounter. With a previously dissatisfied customer, surely we can rely on another service encounter to offer a service recovery that will be satisfying such a previously dissatisfied customer and potentially making him/her a future loyal customer (Surprenant and Solomon, (1987); Bitner, (1990); Tax and Brown, (1998).

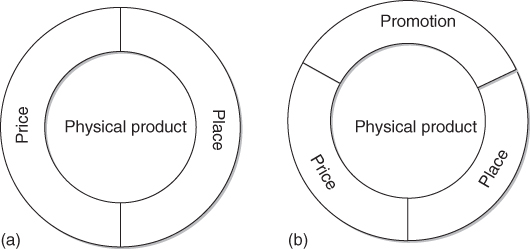

Product, price, and place consist of the rudimentary marketing mix (Figure 1.5a) that is crucial when a product is set for sale. Marketers have reconstituted and/or expanded the mix by including different components to accommodate the differences derived from different goods and the changing customers' needs in the market, aimed at improving sales from time to time. Since the 1960s, product, price, place, and promotion (or simply called 4 Ps) have been widely and steadily used as the pillar components (Figure 1.5b) in the supply-side marketing management to define or describe the marketing mix that can be applied for identifying the niche of a physical product for sale (McCarthy, (1960).

Figure 1.5 The rudimentary and popular marketing mix. (a) Rudimentary 3 Ps and (b) Popular 4 Ps.

In the business world, the effectiveness of marketing a product or service has traditionally and largely depended on how 4 Ps would be coordinated in the product or service marketing and sales process. The fundamental concepts of these components in marketing goods can be briefly summarized as follows:

- A quality physical product has long been the core in the goods marketing. The value of a piece of goods lies in its ability to satisfy the needs of a customer, which is mainly seen in the physical attributes and technical functions of the provided product.

- The price of a product has a lot of impact on its customer's satisfaction level. Quite often, right price is the first step to help push products into the marketplace to get quickly accepted by the customers.

- The price of a product for a designated marketplace should be appropriately set. Varying with socioeconomic statuses, customers in different places frequently have different affordability. They might also have quite different preferences to the physical attributes and technical functions of the provided product because of their cultural preferences and physiological characteristics.

- Promotion plays a critical role in attracting prospective customers in a given marketplace. It varies with marketplaces; it might also change with seasons. This is particularly true when a holiday is approaching. Manufacturers (or retailers) tend to take advantage of the increased number of shopping days if the products are primarily for consumers.

As the competition gets intensified over the years, organizations have shifted their foci to customers, resulting in a customer-focused marketing mix, which is termed as 4 Cs (commodity, cost, channel, and communication) (Tannenbaum and Lauterborn, (1993). The 4 Cs marketing mix model essentially replaces 4 Ps (i.e., product, price, place, and promotion), providing a customer-centric version alternative to the 4 Ps in the goods marketing. Commodity promotes the pleasure realized when a product is used by a customer. Cost considers not only the producing cost but also the use and social costs applied to the customer over time. Channel focuses on the convenience provided to the customer when the product is purchased. Communication highlights the interaction and education to help the customer use the product in an optimal and satisfactory manner.

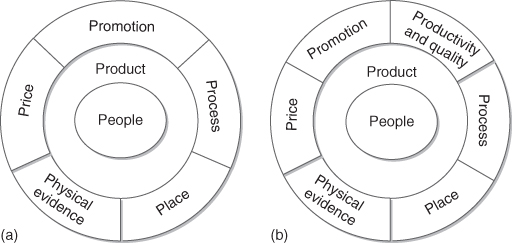

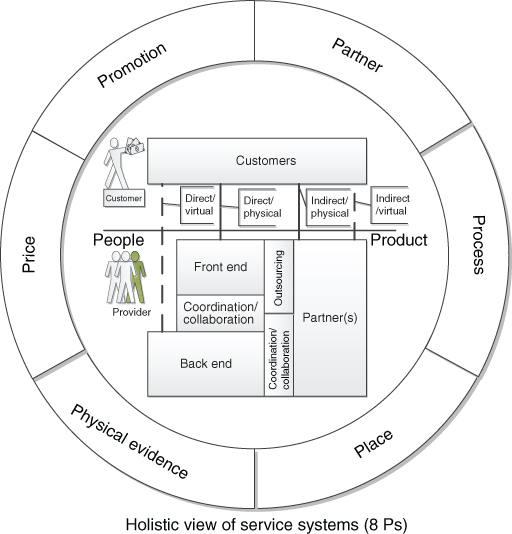

The focus shift from supply to customer clearly shows that organizations know the increasing importance of inclusion of customers in business operations and management. This is especially critical in the service sector as service encounters bundled with additional distinguishing characteristics of service directly impact the corresponding service quality and satisfaction perceived by customers. Over the years, the academics and practitioners have expanded 4 Ps to 7 Ps in the service marketing and delivery model by including three more components, people, process, and physical evidence, to reflect the substantively changed market needs and the evolution of customer-centric service marketing and delivery (Booms and Bitner, (1981); Bitner, (1990).

- People are crucial in service provision. People are human actors centered at service encounters, including employees, customers, and other personnel who are directly or indirectly involved in the service encounters.

- Processes define and govern the procedures, mechanisms, and flow of activities in service encounters, extremely important for service providers to conduct effective marketing and deliver quality and satisfactory services.

- Physical evidence refers to the physical surroundings and tangible cues that could influence the customer's perception of services. As services quite often are intangible, customers intuitively rely on certain tangible cues that can assist them to assess the offered services.

Although we can learn quite a lot from the manufacturing industry, we have inevitably confronted unprecedented challenges in understanding people's roles in rendering services in the service industry. It becomes clear that a service organization must put people (customers and employees) rather than physical goods in the center of its organizational structure and operations to keep businesses competitive (Qiu et al., (2007) (Figure 1.6a). For example, service quality is highly regarded as a comparison of customers' expectations with performance perceived in service provision. Thus, service quality can be extremely subjective. As a result, service productivity and quality are extremely difficult to monitor and measure as they vary with circumstances. Lovelock and Wirtz (2007) include productivity and quality in the service marketing and delivery model, as shown in Figure 1.6b, to warrant that service productivity and quality are well considered throughout service lifecycles. To be competitive, service organizations must control and manage the total lifecycle of service in a cost-effective and efficient manner.

Figure 1.6 The 7 and 8 Ps of services marketing and delivery model.

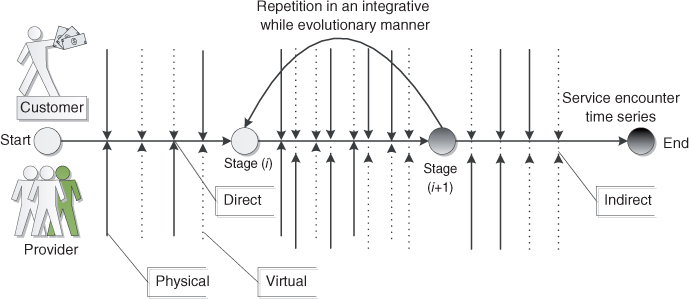

In exploring service encounters in the service industry, the literature has thus developed a series of concepts and models and applied different combinations of 8 Ps to meet the specific needs under different business circumstances, such as marketing, operations and management, and business strategic planning. As discussed earlier, when a service is performed, its consumer and provider interact with each other, directly or indirectly, consecutively or intermittently, physically or virtually, and briefly or intensively, during the process of performing the service. We illustrate a series of service encounters in Figure 1.7 to highlight a variety of possible social and transactional interactions throughout the lifecycle of service.

Figure 1.7 A series of service encounters throughout the lifecycle of service.

It is worthy to mention that this book promotes a new look of service encounters. Instead of focusing on the interacting activities between providers and customers during the process of service deliveries, we explore all the interactive activities between service providers and customers throughout the service lifecycle, from service conceiving to service termination. Consecutive service encounters form a service encounter chain (Svensson, (2004), which can be modeled using an event-based time series. Furthermore, highly correlated service encounter chains thus create a service encounter network. A comprehensive discussion on service encounter networks across the lifecycle of service is provided in Chapter 3.

At first glance, the concepts that are illustrated in Figures 1.3 and 1.4 seem to have no difference from any other illustrations of lifecycles of businesses in any industry. Just like a manufacturing firm, the lifecycle phases in a service organization can be recursive, nested, repetitive, or in parallel during business operations. Indeed, a moment of truth for a service is an instance wherein a customer and a provider-side employee interact to execute the service. An instance might be considerably different from another as the number of involved Ps would change and the constituents of the involved Ps and their relationships could also change (Chase, (1978); Booms and Bitner, (1981); Czepiel et al., (1985); Czepiel, (1990); Bitner, (1990); Bitner, (1992). As indicated in Figure 1.7, various instances could constitute moments of truth in completing the total performance of a designated service. As time goes, to an end consumer, satisfactory services shall evolve with further improved user experiences, while to the service organization services shall evolve iteratively in rendering further enriched and pleasing moments of truth to loyal and new customers.

Physical interactions describe interactions in which a service consumer and a service provider perform service activities to realize the mutual benefits with certain physical evidences that are directly and real-time related to the service required by the consumer. Daily service examples that largely depend on physical interactions include in-person meetings in a physical facility, depositing checks in a bank branch office, eating food in a restaurant, attending a class at school, shopping for merchandises in a shopping mall, or seeing a doctor in a clinic office or a hospital. Without question, physical interactions are radical and key parts of service encounters.

By contrast, virtual interactions describe interactions in which a service provider performs actions to serve a service consumer without providing the physical evidences that are directly and real-time related to the service requested by the consumer. The service encounters are essentially telecommunication or cyber based, such as checking an order status by phone, tracking an order by accessing a website, e-banking, online shopping, online education, or playing computer games over the Internet (Bitner et al., (2000). Virtual interactions have unceasingly increased their roles in service encounters. In particular, self-service systems have received tremendous attentions. On one hand, a service provider can considerably reduce the cost of service management and operations while maintaining a uniformity of services when toward uniformity makes more sense in the services. On the other hand, a service customer can take advantage of the convenience that is entailed by the self-service systems as this kind of service can be consumed anytime and anywhere. Virtual interactions essentially are those interacting activities that are mediated by technical devices (e.g., phones, webs, and social networks).

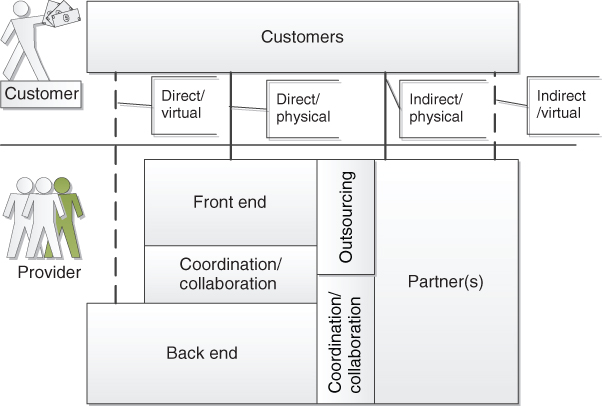

When interactions occur between a service consumer and a service provider without any help or assistance from a third party, they are essentially direct interactions. For example, a patient sees his/her family physician; or a customer has his/her lunch in a fast food restaurant. The services are directly performed between a service provider and a service customer. By contrast, when services that a service provider promises to offer to customers are actually delivered by a partner of the service provider, the incurring service encounters are described by indirect interactions as the customers indirectly interact with the service provider. A perfect example for an indirect interaction in a service encounter will be a service that a customer buys a set of lovely furniture from a local furniture dealer. Many furniture manufacturers contract many local dealers to sell their famous brands. A set of furniture will be delivered to a customer house only after it has been purchased by a customer. To the customer and the furniture supplier, the interaction occurs indirectly. Figure 1.8 graphically shows direct and indirect interactions in service encounters that most likely occur in service operations from an organizational point of view.

Figure 1.8 An organizational view of service encounters.

1.5 The Economic Globalization

Globalization is the phenomenon that highlights the process of integrating nations. Essentially, globalization refers to the exchange of world views, products, services, and cultures around the world (Deardorff and Stern, (2002). The world economy has indeed made extraordinary improvement since World War II. It has been largely credited to the fast advancement in science, engineering, and technology, such as material science, electronics, computers, networks, transportations, and telecommunication technologies over the past half century or so. In particular, the role and power of IT has been exceedingly increased, consequently transforming the ways the business works and people live around the world. Accordingly, people, production systems, computing resources, and information are effectively linked, resulting in the accelerated globalization that has precipitated today's indispensable interdependence of economic and cultural activities.

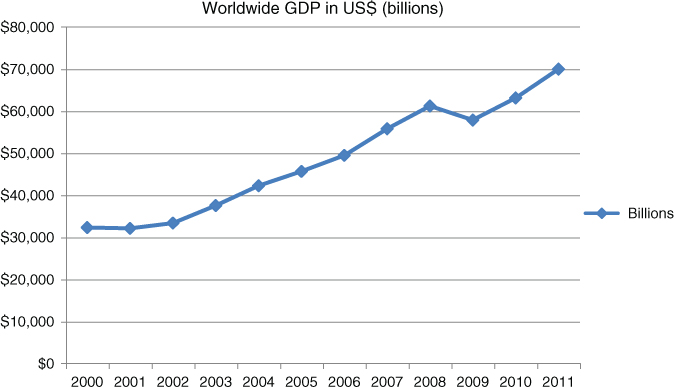

According to Deardorff and Stern (2002), “At the most basic level, globalization is growth of international trade. But it is also the expansion of much else, including foreign direct investment (FDI), multinational corporations (MNCs), integration of world capital markets, and resulting financial capital flows, extraterritorial reach of government policies, attention by (nongovernmental organizations) NGOs to issues that span the globe, and the constraints on government policies imposed by international institutions.” On the basis of the data published by (the World Trade Organization) WTO, the fast growth of international trade has indeed occurred since the 1980s. The international trade growth keeps its fast pace in this new millennium. Figure 1.9 shows the worldwide (gross domestic product) GDP from 2000 to 2011 in US dollars.

Figure 1.9 World GDP data from 2000 to 2011.

(Source: http://www.wto.org).

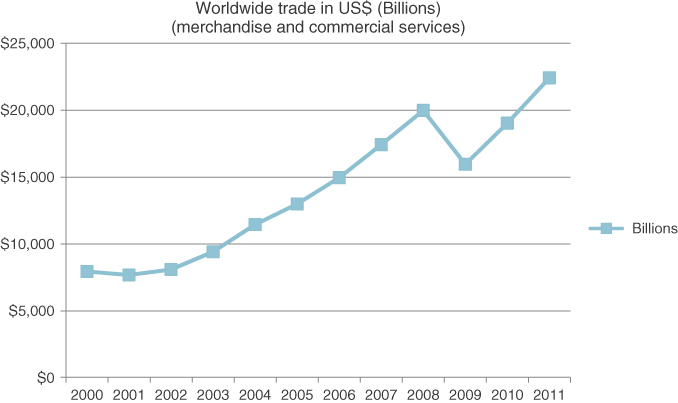

Figure 1.10 World trade data from 2000 to 2011.

(Source: http://www.wto.org).

Figure 1.11 The percentage of world overall trade in GDP from 2000 to 2011.

(Source: http://www.wto.org).

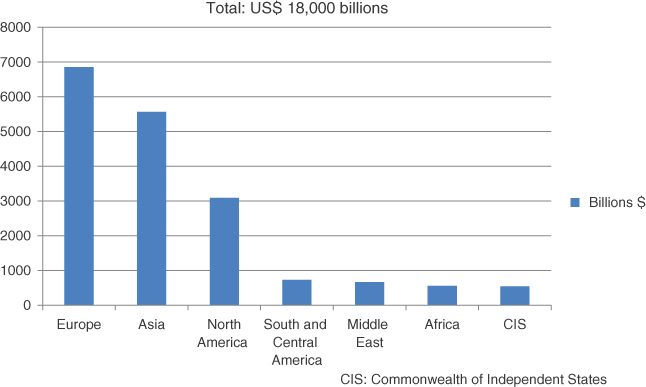

Figure 1.12 2011 world merchandise trade by region: export value.

(Source: http://www.wto.org).

Figure 1.13 2011 world merchandise trade by region: import value.

Although the worldwide GDP dropped in 2009 because of the worldwide financial crisis, the GDP growth in general is the trend. The worldwide economy in 2011 doubled the size of the economy in 2000, appropriately growing 116% in numbers. The international trade had been tripled over the same period, growing from 7687 billion US dollars to 22,424 billion US dollars (Figure 1.10). The percentage of the overall international trade in the worldwide GDP grew at a relatively moderate speed, appropriately from 25% to 32% that resulted in about 28% growth from 2010 to 2011 (Figure 1.11).

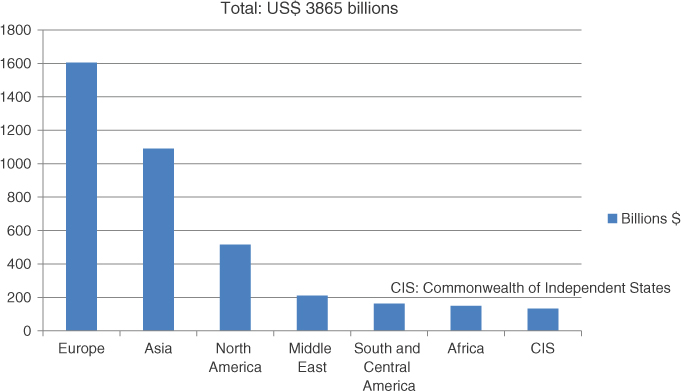

The direct effect of the growing international trade will be surely a more integrated global market. Regardless of where physical products are made, they are made readily available for customers around the world. Because of the accelerated globalization, it is well understood that a typical consumer with an average income in the developing economies would have the increasing opportunity and affordability of purchasing products and services that are traded internationally. Figures 1.12 and 1.13 provide the world merchandise trade in 2011 by region using export value and import value, respectively. Figures 1.14 and 1.15 show the world commercial service trade in 2011 by region using export value and import value, respectively. Overall, people, who live not only in the developed countries but also in the developing countries, are better off with international trades than without (Deardorff and Stern, (2002).

Figure 1.14 2011 world trade in commercial services by region: export value.

Figure 1.15 2011 world trade in commercial services by region: import value.

On the basis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the United States, excluding the goods-producing industries—agriculture, mining, construction, and manufacturing, the service industry, in general, spans all other areas from travel, transportations, logistics, communications, utilities, wholesale and retail, trade, education, finance, insurance, real estate, health care, postal operations, governmental supports, to many other public services. Indeed, the service industry has grown to dominate the developed economies while continuing to develop extremely fast in the developing countries. As an illustrative example, Table 1.1 provides the employment data of the US workforce in July 2012.

Table 1.1 Employment Data of the US Workforce in July 2012

| Industries | Employment (In Millions) | Percentage (%) |

| Trade, transportation and utilities (wholesale trade, retail trade, transportation and warehousing, utilities) | 21.483 | 18.6 |

| Professional and business services | 14.824 | 12.8 |

| Education and health services | 17.828 | 15.4 |

| Leisure and hospitality | 11.996 | 10.4 |

| Government | 21.666 | 18.7 |

| Financial activities | 5.954 | 5.1 |

| Information | 2.134 | 1.8 |

| Other | 4.495 | 3.9 |

| Services sector | 100.38 | 86.7a |

| Manufacturing | 8.444 | 7.3 |

| Construction | 4.133 | 3.6 |

| Agriculture | 2.200 | 1.9 |

| Mining | 0.630 | 0.5 |

| Goods sector | 15.407 | 13.3 |

| Total | 115.787 | 100.0 |

a The percentage is increased from 82.1% in 2006 to 86.7% in 2012.

Source: http://www.bls.gov/ces/.

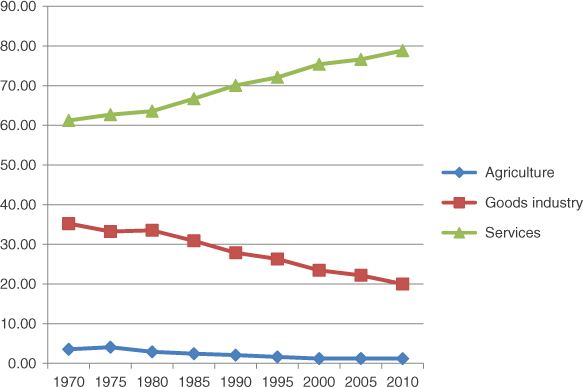

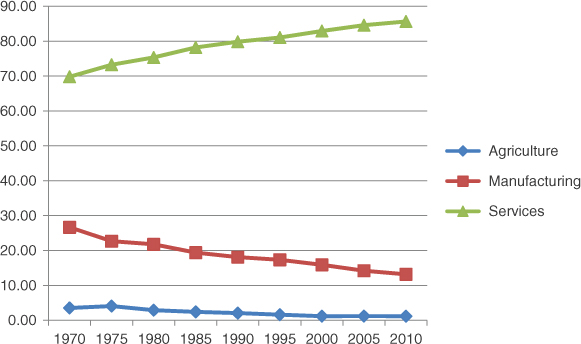

Table 1.1 clearly shows that it is the service industry that employed the majority of workforce in the United States in 2012. Indeed, the percentage of service employees has kept growing over the years. When compared to the growth of GDPs, the US workforce change is well reflected and matched by the similar change pattern in GDPs over the years. Figures 1.16 and 1.17 provide the changes and comparisons among the agriculture, goods, and service industries. At present, the US economy is surely service-led, so are the other developed countries.

Figure 1.16 US GDP percentage data from 1970 to 2010, where industry includes manufacturing and manufacturing services.

(Source: http://www.worldbank.org/).

Figure 1.17 US GDP percentage data from 1970 to 2010, where services include commercial services and manufacturing services.

(Source: http://www.worldbank.org/).

Historically, according to US Department of Commerce (1996), most of the G-7 countries began to see a steady growth in the service industry in the 1960s when the output growth of goods started to slow down. Consequently, the world economy gradually made its structural change. Since the 1980s, the service industry has grown to dominate the developed economies. We have also witnessed that the service industry has been developing extremely fast in the developing countries. Indeed, today's global economy essentially becomes service-led instead of goods-dominant. On the basis of the report published by International Monetary Fund (IMF) (IMF, (2012), the service sector around the world contributed about 63.4% GDP worldwide in 2011. Therefore, the world economy surely became service-led. Along with the economic shift from manufacture to service, the changes in business operations and management are significant. Goods-dominant thinking should be replaced with service-dominant thinking in service engineering, operations, and management. With great detail in discussing the shift from manufacturing to service in the developed economy, we will advocate such a mindset change in practice in Chapter 2.

In summary, the customers worldwide are happily enjoying the exuberant markets to fulfill their daily life needs with the support of home and abroad goods and services. Although the economic globalization is unceasingly accelerated, the world service trade is currently about a quarter of the world goods trade (Figures 1.12–1.15). The world service trade must play a quick catchup as the world economy becomes truly service-led. Therefore, service engineering, operations, and management require new and creative thinking and approaches that can be well applied in practice to help service organizations further leverage the cultural strengths and workforce talents across regions and continents.

1.6 The Evolving and Holistic View of Service

At the end of the day, the realized value of delivered products or services lies in their abilities to satisfy the needs of individuals or businesses. Regardless of what type of products or services we are manufacturing or offering, we must always take significant efforts to ensure that our business operations are cost-effective and efficient and our quality products or services are delivered on time. A competitive organizational structure and its corresponding managerial and operational practices should be well defined and executed. Unless it is a small workshop, a service organization is typically developed and organized based on different while necessary business domain functions in pursuit of common business goals and objectives. Although units are separately operated and managed through their well-defined business domains, they must be collaboratively coordinated across the organization in support of daily business operations to accomplish the defined business objectives (Figure 1.18). For a given organization, surely its business models, organizational structures, and accordingly adopted business domain functions, operations, and management all vary with its unique business nature, size, complexity, and regional and global presence.

Figure 1.18 A typical organizational structure.

Figure 1.19 The manufacturing organizational value chain (Porter, (1985); Weske, (2007).

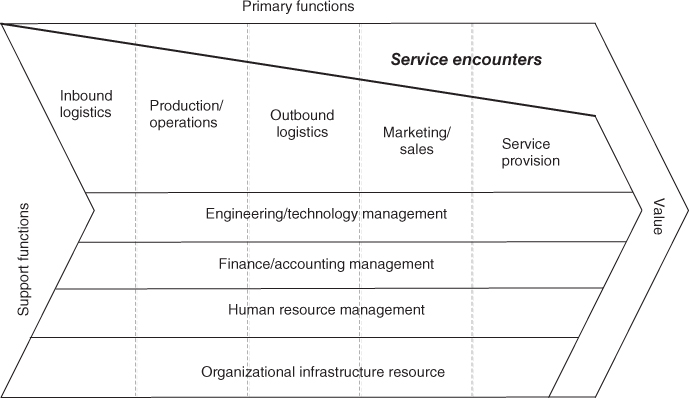

As illustrated in Figure 1.18, a typical organization would have numerous business domains, most likely including sales and marketing, engineering, logistics, production, finance and accounting, and human resource, in order to fully function in delivering the organization's business promise that has been made to its customers. Figure 1.19 then shows how a typical manufacturing business successfully generates a value (e.g., profit) throughout the strategically synchronized organizational value chain (Porter, (1985); Weske, (2007). The profit margin depends on the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of underlying business operations and management to produce quality products, satisfying the needs of its end users that can be individual and/or business customers.

It is typical that the technical characteristics and physical attributes of manufactured products largely present their brands in the market. As compared to the outcomes of manufactured goods, the highlights of services are not simply and strictly seen in the functions of the services and the physical attributes of the associated products that are included in the services, but the abilities of services to satisfy end users' functional and socioemotional needs (Chase and Erikson, (1989); Dietrich and Harrison, (2006); Chase and Dasu, (2008). The competitiveness of services in the market thus largely relies on the efficacy and quality of service encounters. In addition, the focus shift from supply to customer has confirmed that organizations understand the increasing importance of inclusion of customers in business management and operations over the past decade or so. Hence, a service organization cannot well perform services to satisfy customers if service encounters that directly impact service quality and satisfaction are not included and considerably integrated in a gradual and spiral manner on its value chain. Figure 1.20 clearly indicates the substantive change by not only including but emphasizing service encounters on the service organizational value chain. Over the years, the service value chain has essentially evolved from the manufacturing organizational value chain. Nevertheless, the service value chain must continue to evolve by bearing total service encounters in mind to meet the needs of the dynamic marketplaces in the service-led economy (Heskett et al., (1994); Karmarkar, (2004).

Figure 1.20 The service organizational value chain.

The traditional, empirical, or manufacturing-based goods-centric design, development, and delivery of services can be surely applied in practice and might continue to work under certain business circumstances today and in the future. However, we have witnessed that services have evolved substantially and substantively along with the fast development of technologies, societies, and the global economy. It becomes necessary for us to understand how the modern services have evolved from ones not too long ago. Surely, with the comprehensive exploration of service innovation and better understanding of people-centric services in today's information era, we can ensure that our service provision will spiral into the manifests of user experience excellence (IBM, (2004); Cambridge, (2007); Chesbrough, (2011).

Without delving into the details, let us briefly look at a list of core services we rely on at work or primarily in our daily life. Hence, we can capture and abstract the general characteristics of service encounters (Bitner et al., 1994) that are essential for the list of rudimentary services.

- Restaurant Food Services. We choose a recipe we like and then go to a restaurant that serves the recipe. We talk to a waiter/waitress and order dishes from a menu. We eat and then pay for the service. If the foods are delicious, the setting is comfortable, and the waiter/waitress is polite and helpful, we will eat there again. Typically, catering services are driven by the quality of foods and customers' perceived pleasure and service satisfaction. Intuitively, we consider that the catering services are act-based as direct and physical service encounters are necessary.

- Car Services. For a regular maintenance, we call a car service shop we choose and schedule an appropriate mileage-based service recommended by our car manufacturer. On the scheduled day, we bring the car that is scheduled for its regular maintenance service to the shop. After we confirm with a receptionist on the needed maintenances, we drop the car there and leave for work. A mechanics might call us if there would be something to discuss, such as different problems found during the service, the need for replacing extra parts, the final charge, and/or a different time to pick up. We pick up the car after we pay the due. Again, we intuitively think that car services are generally act-based as direct and physical service encounters mainly occurs throughout the maintenance service process.

- Residential Gas or Electricity Services. We call a local office of a gas or an electricity service provider we choose and inform the service provider of the date we move in. When we move out, we simply do the same. We pay a bill based on the monthly usage of gas or electricity. As discussed earlier, unless there would be a problem with power lines, gas pipes, or a discrepancy in a monthly bill statement, we might not physically interact with the service provider at all. At first glance, we think the utilities services are supply-based. Indeed, indirect and virtual interaction types of service encounters dominate across the corresponding service process in the utility industry.

- Resident Education. We register a course that can be a required core course or a selective one for a degree or diploma. We go to school to attend instructor-led lectures or lab sessions. We listen to the lectures provided by an instructor. We frequently discuss with the instructor or classmates on a variety of topics related to the lessons. We surely complete assignments and take exams or finish projects in due course. Typically, we think resident instruction-based education services are act-based as direct and physical service encounters dominate in the whole educational service process.

- Online Training. We register a training course. No matter where we are, we can log on whenever we have time and an Internet connection. We read lecture notes and watch or listen to recorded lectures via a variety of online social media. We might discuss problems with other trainees who have registered the same training class. The discussions can be done synchronously or asynchronously. By leveraging a variety of online supports, we will complete assignments, take exams, or finish projects as needed. Without question, online training is quite different from resident instruction-based education. As this particular type of online training seems that the offered services are delivered using an on-demand model, it is extremely similar to a utility-type service. Intuitively, we think online training services are supply-based as indirect and virtual service encounters dominate in this type of training process.

- Federal Bureaus or State Agencies. We can use a driver license renewal service as a typical example of utilizing state-level governmental services. We fill in a renewal form online. A letter from the Department of Transportation of the state we live in will arrive in a few days, which informs us of the time and location to have our driver licenses renewed. We show up at the designated office on the date indicated in the appointment letter. A staff at the office will assist us in the whole renewal process. A photo will be taken, a signature is then required, and accordingly a new driver license will be issued. Service encounters seem to take a variety of possible social and transactional interactions. We typically perceive that the services provided by both federal and state agencies consist of a series of acts of public services.

- Global Project Development. Let us make up a fictional virtual project team first. A software project development team has six small groups of people, populating in six different geographic regions. Each group has certain unique skill sets of from 5 to 15 talent employees, including a software designer, a group architect, programmers, quality assurance staff, business analysts, and a group manager. A top-level management group, managing the entire virtual project team, consists of one team manager, one team architect, and one team business analyst. A project draft specification might be brainstormed when the top-level management group meets with a group of customer representatives. The project specification might be revised and enriched as time goes. Unless the project is completed, it is typical that the specification will keep changing to some extent. Surely each revision will be the outcome of numerous onsite or virtual meetings. Customer representatives could be directly or indirectly contacted by group members if necessary. We surely understand that a project requiring a global virtual team is usually big and complex and its development process is frequently long and complicated. In general, we perceive that global project development services surely are act-based, requiring a series of interactions and coordination, physically and/or virtually. Service encounters throughout the development cycle of global project development services are collaborative in nature.

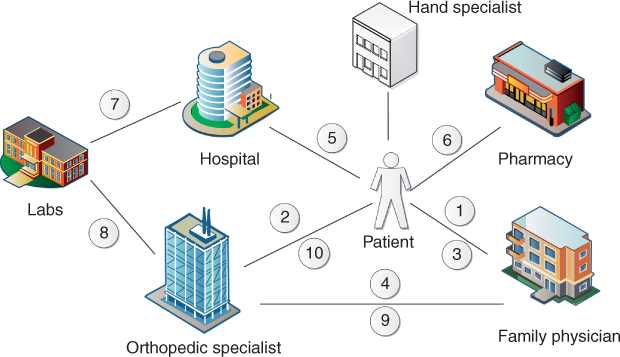

- Health care Service Networks. We use an outpatient, who has a small hand lump removed through a health care service network, to show how a typical US health care service is performed. Figure 1.21 illustrates the process and associated steps that are usually taken by the outpatient to complete his treatment and get fully cured and recovered. Step 1, the patient has to see his family physician (Dr. A) first. He is usually referred to an orthopedic or hand specialist. Step 2, we assume that the patient makes an appointment with the referred orthopedic specialist (Dr. B) and sees the orthopedic specialist accordingly. Dr. B diagnoses the hand lump and then schedules an operation for him. In order for Dr. B to do a hand surgery, Dr. B asks the patient to get his physical examination done by Dr. A before the scheduled operation. Step 3, the patient has to see Dr. A to get his physical exam. Step 4, Dr. A informs Dr. B's office of the result of his physical exam. Step 5, the patient shows up in the hospital where his hand operation will take place. Dr. B has the scheduled operation completed. Step 6, the patient gets some prescribed medicines by Dr. B from a pharmacy. Step 7, the removed neoplasm is sent to some labs for further diagnosis. Step 8, the lab result that shows the neoplasm is benign and is delivered to Dr. B's office. Step 9, Dr. B sends a final report of the treatment for the patient to Dr. A's office. Step 10, the patient sees Dr. B., Dr. B checks how the recovery from the surgery goes. The patient gets released once Dr. B determines that the neoplasm is completely removed and patient's hand gets fully cured and recovered from the surgery. Apparently, a health care service is act-based, which mainly requires a series of interactions and coordination, physically and directly. Service encounters throughout the whole process are indeed collaborative in nature. The involved health care personnel should be coordinated in a timely and collaborative manner; the patient must be also well collaborated in order to have the operation service and treatment completed in a quick, successful, and satisfactory manner.

Figure 1.21 A typical US health care service network.

From the above brief discussion on service encounters that were derived from a list of selected core services at work or in our daily life, we can roughly provide a comparison table (Table 1.2) to list the key variations of different services by presenting what customers' general perceptions of these services would be and how a series of service encounters play a pivotal role in the noticeable evolution of the service organizational value chain (Figure 1.20). Banking, online banking, shopping, online shopping, tourism, and transportation services that well serve our daily life needs are also included in Table 1.2. Note that the differences perceived by customers are derived from their perceptions of services throughout the lifecycles of the consumed services.

As the perceptions of services are primarily subjective, the corresponding differences intuitively come from the differences acquired from service encounters by customers during the periods when they receive the offered services. We do not try

Table 1.2 Rough Comparisons of Customers' Service Perceptions Across Different Types of Services to present perfect and comprehensive understandings of service encounters in this introductory chapter. We use Table 1.2 to simply show a few of examples to provide some clarifications or explanations of the existence of different service definitions mentioned earlier while highlighting the pivotal role of service encounters in service. The readers should also understand that there surely exist other forms of service definitions in academia and practice.

From the approximate comparisons provided in Table 1.2, we can further confirm the three main definitions that have been radically formed from customers' general perceptions of services.

- When a service is performed, if its service encounters are largely physical, intensive, and direct from the customer's perspective, then a social and transactional performance is perceived as the centerpiece of the service. This entails that service is considered as a direct performance of beneficial activities.

- By contrast, when a service is performed, if its service encounters are mainly virtual, brief, and indirect from the customer's perspective, then the usage of a service product or resource is perceived as the centerpiece of the service. Accordingly, service is quite often considered as the supplying of utilities, commodities, or digitalized media.

- In addition, people receive many societal function types of services, such as societal function services that are provided by governmental agencies. People easily view the related service encounters to have a public service nature. Service is thus essentially considered as a performance of supporting the needs for the public.

| Services | Service Encounters | |||||

| Type | Product | Physical Versus Virtual | Direct Versus Indirect | Brief Versus Intensive | Process | Customers' General Perceptions of Services |

| Restaurant foods | Foods | Physical | Direct | Brief | Short and simple | Catering acts |

| Car services | Fixing or maintenance | Physical | Direct | Brief | Short and simple | Providing fixing acts |

| Gas or electricity | Utilities | Virtual | Combined | Brief | Long and simple | Supplying acts |

| Banking | Saving and checking accounts | Physical | Direct | Intensive | Long and simple | Supplying acts |

| Online banking | Saving and checking accounts | Virtual | Combined | Brief | Long and simple | Supplying acts |

| Shopping | Merchandises | Physical | Direct | Intensive | Short and simple | Selling acts |

| Online shopping | Merchandises | Virtual | Combined | Brief | Short and varying | Selling acts |

| Transportation | Delivery | Physical | Combined | Brief | Short and simple | Supplying acts |

| Tourism | Tour planning | Varying | Combined | Intensive | Short and complex | Providing tour acts |

| Health care | Knowledge | Physical | Direct | Intensive | Varying | Providing diagnostic, care, and treatment acts |

| Resident education | Knowledge | Physical | Direct | Intensive | Long and simple | Providing educational acts |

| Online Education | Knowledge | Virtual | Combined | Brief | Long and complex | Providing educational Acts |

| Federal bureaus or state agencies | Polices and, regulations compliances, or law enforcements | Varying | Direct | Brief | Short and simple | Providing public supports acts |

| Global project development | Knowledge | Varying | Combined | Varying | Varying | Providing knowledge acts |

Overall, we can find that it is the “performance” or “act of performing” in service provision that creates benefits for both service providers and service consumers. As service providers, in addition to the service delivery-based interactions that are mainly perceived by customers, we know that the design, development, and preparation of service encounters must be included and well executed across the service value chain (Figure 1.20). Customers consume and perceive services through a list of service encounters that can be delivered, face-to-face or virtually, directly or indirectly. However, in a systemic perspective, customers are heavily involved in other phases of the service lifecycle including inputs to service design and feedback on consumed services. In other words, the real value of service is the total perceived value of the outcomes developed and accumulated from a series of service encounters that truly cross the lifecycle of service.

Figure 1.22 A new perspective of service offering and delivering model.

Furthermore, the increased degree, magnitude, and/or scope of automation, outsourcing, customization, offshore sourcing, business process transformation, e-business, and self-services continue to evolve. Service provision thus becomes more complicated and challenging. Consequently, service organizations demand a higher efficiency and better cost-effectiveness in service management, engineering, and operations across their service value chains, focusing on further improving their competitiveness in the global service-led economy. We fully understand that the value of service is the total perceived value of the quality outcomes realized through a series of service encounters across the service lifecycle. Hence, we must adopt a new holistic service perspective to study service, aimed at identifying right approaches to help service organizations learn, develop, perform, and improve their offered services. The new holistic perspective of services (Figure 1.22) should simultaneously include the following views:

- Systems or Systemic View. A system, focusing on the interdependence of relationships created in an organization, is composed of regularly interacting or interrelating groups of activities within the organization (STWiki, (2012). Thus, a service organization essentially is a service system that consists of a number of interacting and collaborative business domains systems (Qiu, (2007). The systems view is then a perspective of looking at the service organization as a collection of business domain systems that create a whole, allowing us to understand and orchestrate the interacting activities among these business domains systems. Simply put, a corresponding systemic study should focus on the relationships between those systems to determine how they affect the whole on the trajectory of realizing the business goals and objectives of the service organization.

- People-Centric View. Both supply side and customer side should be well explored.

- Global View. Partnership and cultural aspects should be fully considered. A new 8 Ps should be applied in the service provision model.

- Lifecycle View. As discussed earlier, the value of service is the total perceived value of the quality outcomes realized through a series of service encounters across the service lifecycle. Well-designed service encounters thus must span services from beginning to end.

1.7 Summary

In this chapter, we looked into the insights of service from different perspectives. We now understand that customers consume and perceive services through a list of service encounters that occur in the process of service deliveries and beyond. However, service encounters, which are interactions between customers and providers, can occur in different ways, face-to-face or virtually, directly or indirectly. To service providers, we know that customer interactions go beyond the service delivery processes and must include the contacts during the design, development, and preparation of service encounters. Indeed, customers contribute significantly to the design, development, and preparation of service encounters in order to carry out competitive services to prospective customers (Ahlquist and Saagar, (2013). Therefore, the value of service is the total perceived value of the outcomes cocreated by providers and customers from a series of service encounters throughout the service lifecycle.

As a service is largely people-centric, truly cultural and bilateral, the type and nature of a service dictates how a service is performed, which accordingly defines how a series of service encounters could and should occur throughout its service lifecycle. The type, order, frequency, timing, time, efficiency, and effectiveness of the series of service encounters throughout the service lifecycles determine the quality of services perceived by customers who purchase and consume the services (Bitner; (1992); Chase and Dasu, (2008). It is largely true that the perceived service quality by customers substantially impacts the satisfaction and loyalty of the customers. We will fully explore all the aspects of service encounters across the lifecycle of service, chapter by chapter throughout this book.

We never try to craft our definition of service to be more comprehensive and precise than those that have been proposed by many pioneers in the global service research, education, and practice community over the years. However, we do need an appropriate, holistic, and sound definition to lay out the solid foundation for this book. Therefore, regardless of how many versions of service definition exist in academia and practice, one consistent definition is essential for the following chapters of this book. Identifying such an appropriate and sound definition of service surely becomes necessary, which naturally becomes the focus of our next chapter.

References

- Ahlquist, J., & Saagar, K. (2013). Comprehending the complete customer. Analytics—INFORMS Analytics Magazine, May/June, 36–50.

- Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: the effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 69–82.

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71.

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994). Critical service encounters: the employee's viewpoint. The Journal of Marketing, 58, 95–106.

- Bitner, M. J., Brown, S. W., & Meuter, M. L. (2000). Technology infusion in service encounters. Journal of the Academy of marketing Science, 28(1), 138–149.

- Booms, B. H., & Bitner, M. J. (1981). Marketing strategies and organization structures for service firms. Marketing of Services, 47–51.

- Cambridge. (2007). Succeeding through service innovation. Cambridge Service Science, Management and Engineering Symposium, July 14–15, 2007.

- Chase, R. B. (1978). Where does the customer fit in a service operation? Harvard Business Review, 56(6), 137–142.

- Chase, R. B., & Dasu, S. (2008). Psychology of the experience: the missing link in service science. Service Science, Management and Engineering Education for the 21st Century, 35–40, ed. by B. Hefley and W. Murphy. US: Springer.

- Chase, R. B., & Erikson, W. (1989). The service factory. The Academy of Management Executive, 2(3), 191–196.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2011). Open Services Innovation: Rethinking Your Business to Grow and Compete in a New Era. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Czepiel, J. A. (1990). Service encounters and service relationships: implications for research. Journal of Business Research, 20(1), 13–21.

- Czepiel, J. A., Solomon, M. R., & Surprenant, C. F. (1985). The Service Encounter: Managing Employee/Customer Interaction in Service Business. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Deardorff, A., & Stern, R. (2002). What you should know about globalization and the world trade organization. Review of International Economics, 10(3), 404–423.

- Dietrich, B., & Harrison, T. (2006). Serving the services industry. OR/MS Today, 33(3), 42–49.

- Flood, R. L., & Carson, E. R. (1993). Dealing with Complexity: an Introduction to the Theory and Application of Systems Science, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer.

- Heskett, J. L., Jones, T. O., Loveman, G. W., Sasser, W. E., & Schlesinger, L. A. (1994). Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 164–174.

- IBM. (2004). Services Science: A New Academic Discipline? IBM Research.

- IMF. (2012). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved Oct. 10, 2012 from http://www.imf.org/.

- ITIL. (2011). Information Technology and Infrastructure Library. ITILv3. Retrieved Oct. 10, 2012 from http://www.itil-officialsite.com/AboutITIL/WhatisITIL.aspx.

- Karmarkar, U. (2004). Will you survive the services revolution? Harvard Business Review, 82(6), 100–107.

- Lovelock, C. H., & Wirtz, J. (2007). Service Marketing: People, Technology, Strategy, 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- McCarthy, J. (1960). Basic Marketing – A Managerial Approach. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin.

- Morris, B., & Johnston, R. (1987). Dealing with inherent variability: the difference between manufacturing and service? International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 7(4), 13–22.

- Porter, M. (1985) Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York: Free Press.

- Qiu, R. G. (2007). Enterprise Service Computing: From Concept to Deployment. Chapter 1 in Information Technology as a Service, 1–24, ed. by Robin Qiu. Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing.

- Qiu, R. G. (2013). We must rethink service encounters. Service Science, 5(1), 1–3.

- Qiu, R. G., Fang, Z., Shen, H., & Yu, M. (2007). Editorial: towards service science, engineering and practice. International Journal of Services Operations and Informatics, 2(2), 103–113.

- Samuelson, P., & Nordhaus, W. (2009). Economics, 19th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Svensson, G. (2004). A customized construct of sequential service quality in service encounter chains: time, context, and performance threshold. Managing Service Quality, 14(6), 468–475.

- STWiki. (2012). Systems Theory. Wikipedia. Retrieved Oct. 10, 2012 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Systems_theory.

- Sullivan, A., Sheffrin, S., & Perez, S. (2011). Economics: Principles, Applications and Tools, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Surprenant, C., & Solomon, M. (1987). Predictability and personalization in the service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 86–96.

- Tannenbaum, S. I., & Lauterborn, R. F. (1993). Integrated Marketing Communications. Lincolnwood, IL: NTCBusiness Books.

- Tax, S., & Brown, S. (1998). Recovering and learning from service failure. Sloan Management Review, 40(1), 75–88.

- U.S. Department of Commerce. (1996). Service Industries and Economic Performance. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved on Dec. 10, 2012 from http://www.esa.doc.gov/sites/default/files/reports/documents/serviceindustries_0.pdf.

- Vargo, S., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17.

- Weske, M. (2007). Business Process Management: Concepts, Languages, Architectures. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.