Chapter 2

Definition of Service

Today's business environments are characterized with advanced communications, accelerated economic globalization, and increased automation and open source innovations. As we have witnessed, the resultant vibrant but also complex service provision has created higher quality and healthier lives around the world. For a service organization to stay competitive, however, the unceasingly intensified competition demands that the organization must keep improving the efficiency and cost-effectiveness in service management, engineering, and operations across its service organizational value chain.

Over the years, service is typically considered as an application of specialized knowledge, skills, and experiences performed for the benefit of another (Vargo and Lusch, (2004); Spohrer et al., (2007). Quite often, services to customers are regarded as being perishable, heterogeneous, and intangible, commonly provided for either individuals or businesses to create desirable values to satisfy their needs (Sampson and Froehle, (2006); Qiu et al., (2007). Hence, to find an appropriate definition of service in a broad sense to cover a variety of service areas seems difficult and challenging.

Service as a word in economics is mainly defined as an act of helpful activity, the supplying of transportation, communication, and utilities or commodities, or the providing of assistance, accommodation, or leisure activities. Although its meaning might vary with circumstances, a given service substantively implies performing an action or a series of actions. Indeed, no matter what a service product is embedded as part of the offered service, the service is being executed only when the act of a designated service activity is performed. The value of the service thus largely depends on when, where, and how the process of relevant service activities gets executed.

From Chapter 1, we understand that a sound, solid, and holistic definition of service is essential for this book, regardless of the existence of many versions of service definition in academia and practice. Therefore, in order to find a sound, solid, and holistic definition of service we need, we must revisit and rethink the process of generating service values by exploring the following aspects of service:

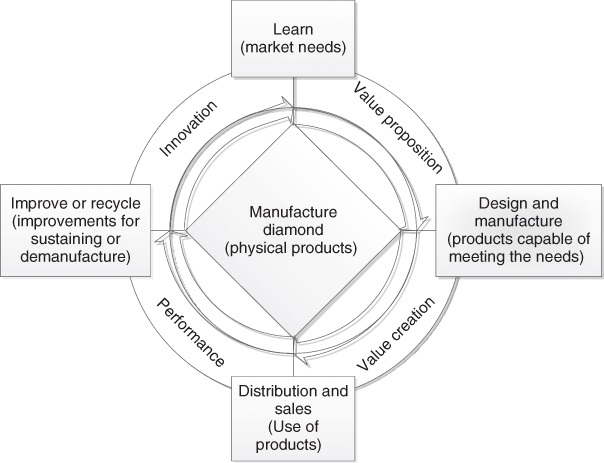

Figure 2.1 Priority shifts in operations and management in manufacturing.

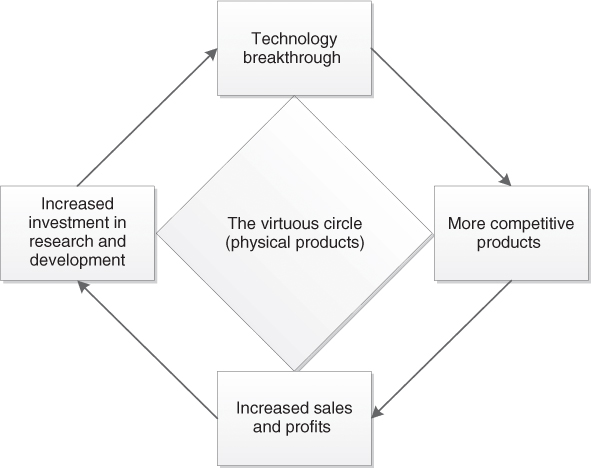

Figure 2.2 The typical virtuous circle well recognized and adopted in manufacturing.

- We must explore how the distinguishing characteristics in service provision differentiate a service execution process from one used in manufacturing.

- We must understand how the globalization of economy impacts the evolution of the service lifecycle.

- We must look into the total service lifecycle, spanning from service concept conceiving, to service phasing out, aimed at capturing the real insights of service-oriented business operations and finding scientific methods and methodologies to help service organizations foster service design, development, delivery, operations, and improvement in a competitive manner.

2.1 From Manufacturing to Service: The Economic Shift

Not long ago when the worldwide economy was dominated by manufacturing, both academics and practitioners paid much attention to the design, development, production, and innovation of physical products. Except for studies that were radically focusing on the employee–customer encounter and service quality in the service marketing research and practice, people's social, physiological, and psychological roles were largely blurred and barely seen in the manufacturing business operations and management (Figure 2.1).

We can clearly see that Figure 1.4 is directly derived from Figure 2.1. In other words, the priority shifts along with the changing phases defined in the service diamond relationship (Figure 1.4) are similar to the ones defined in the manufacture diamond relationship (Figure 2.1). This is surely not a surprise as manufacturing had played the dominative role in the world economy for over a century or so. Inertial thinking is normal to the majority of human beings, resulting in that many service organizations run their services using manufacturing mindsets.

More specifically, as physical products had been essentially the focus over the last century, manufacture/service organizations had been dominantly considered as technology- or product-driven entities, paying much attention to their product features/functions, applied materials, production/automation means, distribution, and productivity. Hence, it is the product that determines the value of a business which is the mindset of an organizations' executives in business operations and management (Chesbrough, (2011a) (2011b). The physical product surely is the implicit star in a manufacturing organization. A competitive manufacturing business is thus driven by the closed innovation paradigm, focusing on technical breakthroughs from its increased investment in the internal research and development (R&D). Figure 2.2 shows the typical virtuous circle that has been well recognized and adopted in manufacturing (Chesbrough, (2003).

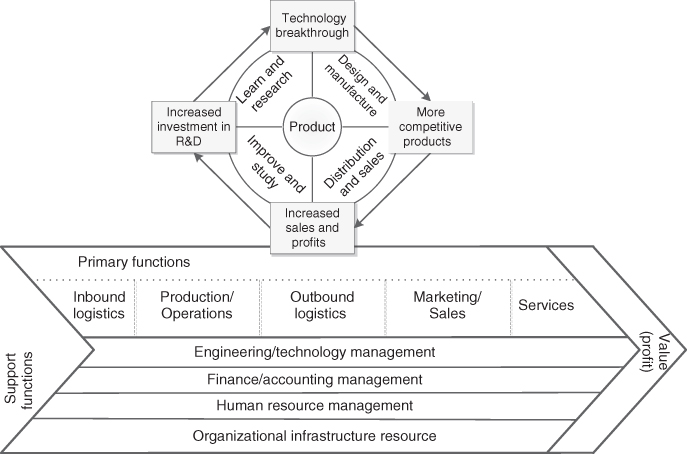

The typical virtuous circle in manufacturing relies heavily on the realized technology breakthroughs in a timely manner to stay competitive (Figure 2.3). Innovations in manufacturing are goods-oriented. In other words, manufacturing organizations primarily invest in the following areas to provide competitive products for mature and emerging markets:

- Product Features/Functions. The organizations rely on technology breakthroughs to add newly discovered features/functions to the products, aimed at outperforming competitors considerably in terms of the products' technical capabilities of meeting the needs of customers.

- Materials. The organizations increase the performance and reliability of the products using the innovations, resulting in further improved customers' satisfaction from the purchased goods.

- Production Automation. The organizations improve the quality of the products and reduce the cost of productions, to improve profit margins and maintain goods quality brands.

- Supply Chain and Logistics. The organizations further optimize all transportation, storage, and distribution of raw materials, work-in-process parts, finished goods, and other resources from the point of origin to the point of consumption, focusing on improving the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the flow of the formed organization networks internally and externally. The lead time and cost of manufactured products in production and on the supply chain thus get cut further.

Figure 2.3 Competitive manufacturing driven by goods-oriented innovations.

Without a second thought, the innovation-based virtuous cycle must center and indeed has truly centered at physical products in manufacturing organizations.

In general, the value for an organization is the benefit provided for customers, employees, partners, and investors. The value recognized as a benefit indeed varies with the stakeholders and time. At a different time, the benefit for a different stakeholder might be realized in a different form. In manufacturing, the benefit is usually realized through product-centric business operations that seek to leverage prices over costs by means of organization, policies, management, operations, technology, finance, incentives, and other factors throughout the manufacturing value chain (Figure 2.3).

As the manufacturing productivity and quality of products have been significantly improved, the standard of living has been considerably improved. Although the means that are used in gauging the standard of living vary with political and economic societies and geographic areas, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, the world witnessed significant transformations in many aspects of well-being that were mainly driven by the long-established industrializations and well-improved productivities in the developed economies. As a result, the global economy gradually shifted its focus from manufacturing to services, aimed at further improving the quality of lives around the world. It has been well recognized that the dawn of information era has accelerated the shift.

The quality of life currently takes into account not only the material standard of living but other intangible values of living that are service-oriented and largely subjective. Indeed, people are increasingly demanding supportive, pleasant, and value-added services. The social and perceptive concepts and measures, including success, happiness, satisfaction, and the like, are frequently applied and used to measure the outcomes of performed services. Thus, the measurements used for gauging consumed services are substantively different from the performance measurements such as physical features and technical functions that have been mainly used in manufacturing. Without identifying all the characteristics of manufacture and service, a brief comparison between manufacture and service using the simplified lifecycle phases in Figures 1.4 and 2.1 is provided in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Highlights of the Operational and Managerial Priorities in the Service Industry

| Lifecycle Phases | General Characteristics | Highlights of the Changes in | ||

| Manufacture | Service | Manufacture | Service | Service Operations and Management |

| Learn | Learn | Market analysis: physical features and functions | Market analysis: services to meet the customers' perceived values and their daily needs of service product features and functions | Customers' perceptions of services including service products |

| Design and manufacture | Develop | Physical product realization: functionality, quality, automation, and cost | Resource development: capability of delivering, quality assurance, and cost | The capacity of resources and capability enabled by the service providers |

| Distribution and sales | Deliver | Physical product distribution efficiency and price | Satisfactory acts of performing designated service deliveries and price | Service encounters |

| Improve or Recycle | Improve | New features and functions | New acts to increase customers' perceived values and more capable resources | Enhancements in support of service encounters |

Many scholars and practitioners have attempted to differentiate service from goods on one or more dimensions ultimately arriving at a continuum (Bell, (1981); Bowen, (1990); goods are arrayed at one end and service on the other end. It is typically true that there is considerable overlap between the two (Solomon et al., (1985). In this book, we incline to have our main discussions by inclining to the service end. However, for a service, we must understand that goods are frequently the conduits of service provision. Therefore, the physical attributes and technical characteristics that specify the goods are surely indispensable to the service.

Let us look into two excellent examples to see how the discussions are reflected in real life. One is a typical car repairing service. The other is a purchase of a popular product, iPad, from the Apple online store.

- Car Repairing Service. When we know there is a problem with a car, we call a car service shop that we choose and schedule an appointment. On the scheduled day, we bring the car that is scheduled for a repair service to the shop. After we confirm with a receptionist on the needed repair service, we drop the car there and leave for work. A mechanic might call us if there would be something to discuss, including the severity of the identified problem, the misunderstanding or misinterpreting of the stated problem, or other problems found during the conducted diagnosis process, other necessary maintenances recommended by the mechanics, the final charge, and/or a different time to pick up. We pick up the car after we pay the due. Throughout the repair service process, we understand that a series of service encounters must occur. Indeed, the appropriate and timely occurrence of each interacting activity on the service encounter chain ensures user experience excellence in an integrative manner, resulting in that the repair service gets executed in a satisfactory manner.

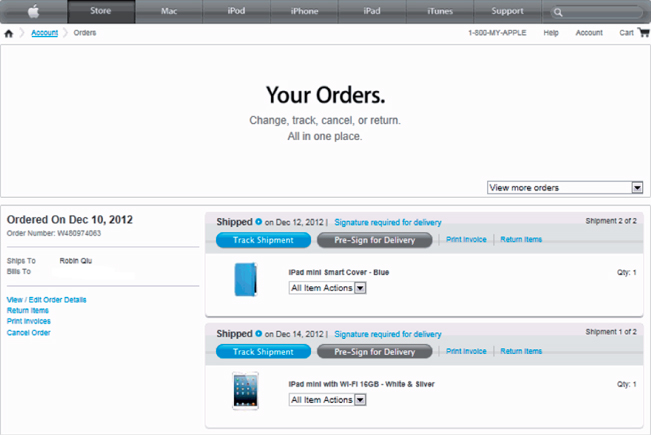

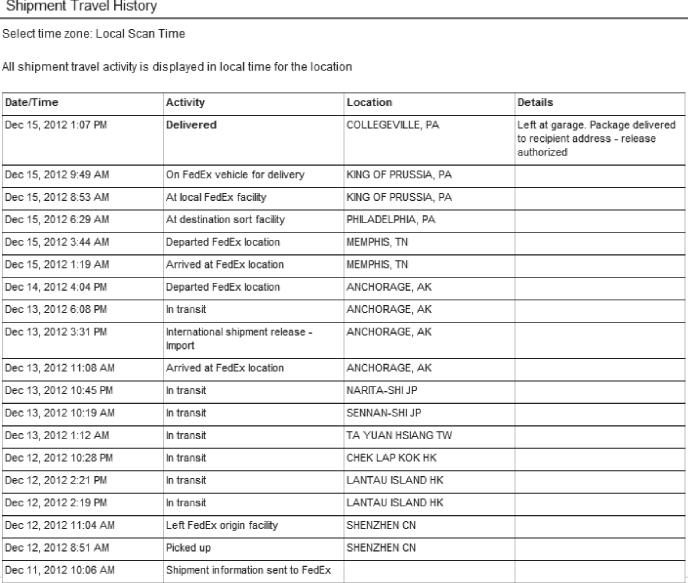

- iPad Purchase and Delivery Service. As a customer, I was amazed by how Apple Inc. can deliver millions of products to customers on time. It is nothing special these days that you can track the delivery process of an ordered product through the Internet, regardless of your choice of a transport organization. However, to deliver millions of products made overseas to customers on the promised dates is exceedingly fascinating. I still remember that the first generation of iPad officially became available for preorder on March 12, 2010. I ordered one on that day. The Apple online store provided several handy and optional shipment alert services that allowed customers to monitor their shipments through Apple's contracted delivery firms. I received my ordered iPad on April 3, 2010. April 3, 2010 was the date that Apple promised on March 12, 2010 that the first generation of iPads would be released and delivered to millions of US customers. Although I cannot get the order history information that is over 18 months old, Figures 2.4–2.6 show good examples of highly coordinated and collaborated processes of purchasing, manufacturing, customs, and shipments across countries that are managed in an effective and satisfactory manner. In addition to calling relevant customer service representatives, we can easily interact with the Apple online store, UPS, or FedEx websites to change orders, monitor the shipments, change how we want the ordered products to be delivered to fit into our busy daily schedules. Customer-centric and satisfaction-focused business operations and management have surely contributed to the success of Apple's business. It is the service that helps sell the product! More discussion on Apple's customer-centric and innovative approach will be further provided in later chapters.

Table 2.1 and the above-discussed two examples surely help us to get a better understanding of how certain priorities have been shifted in business operations and management in the industry. Service encounters play a fundamental role in service offerings, clearly indicating that people's social, physiological, and psychological traits are critical in services (Solomon et al., (1985); Surprenant and Solomon, (1987); Chase and Dasu, (2001). However, these traits are extremely challenging to measure, monitor, and control in service operations and management. Therefore, we understand that, substantively different from traditional manufacturers that have put products in focus, service organizations must put employees and customers at the center of concerns in business operations and management (Heskett et al., (1994); Loveman, (1998); Qiu et al., (2007); Schneider and Bowen, (2010).

Figure 2.4 Online purchase services provided by Apple online store.

(Source: Apple.com).

Figure 2.5 Product in-transit information provided by UPS.

(Source: UPS.com).

Figure 2.6 Product delivery information provided by FedEx

(Source: FedEx.com).

Even in manufacturing, for farsighted manufacturers in the developed economy, although their product features and functions might lose their competitiveness over time, they recognize that their service components could considerably distinguish themselves from their competitors. Therefore, enterprises are keen on building highly profitable service-oriented businesses by taking advantage of their own unique engineering and service expertise, aimed at shifting gears toward creating superior outcomes to optimally meet their customer needs in order to stay competitive (Rangaswamy and Pal, (2005). General Electric, IBM, Apple, Oracle, HP, and many worldwide bellwethers are great examples in repositioning themselves toward the service-oriented businesses (Qiu et al., (2007).

The economic shift from manufacturing to service makes organizations rethink their business strategies and revamp their organizational structures and operational processes to meet the customers' fluctuating demands on services in a satisfactory manner. World-class enterprises across the board, in general, are eager for seeking new business opportunities by streamlining their business processes, building complex and integrated while more efficient IT-enabled systems, and embracing the worldwide Internet-based marketplace. It is well recognized that business process automation, outsourcing, customization, offshore sourcing, business process transformation, and self-services by leveraging the ubiquitous and pervasive networks and wireless communications became another business wave in today's evolving global service-led economy.

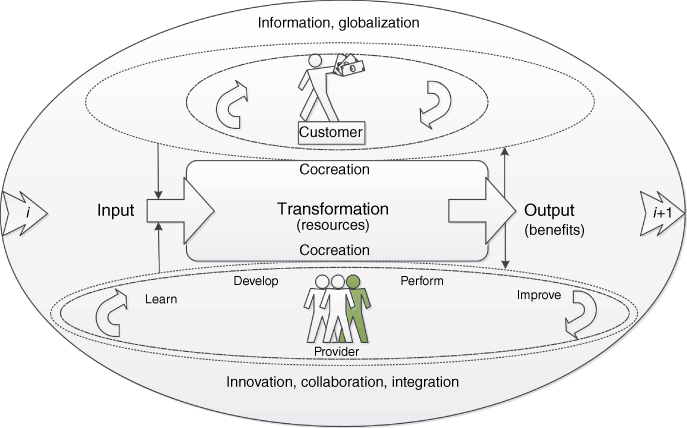

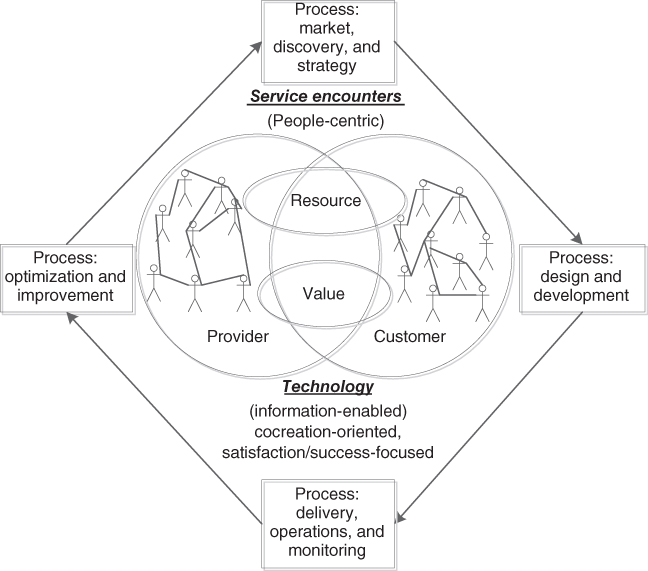

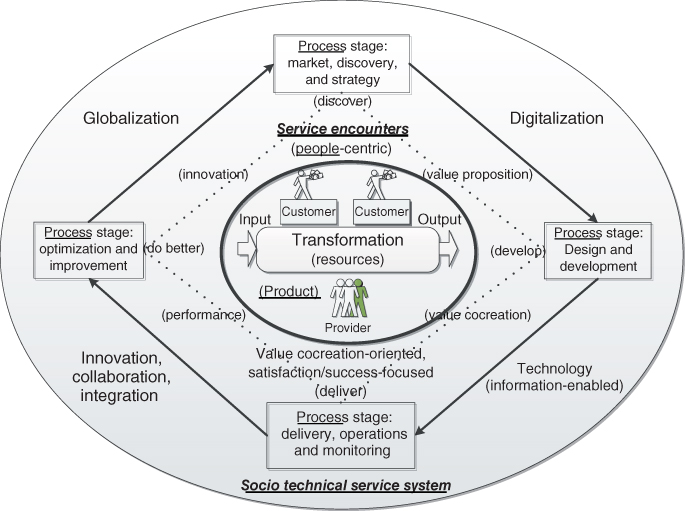

Indeed, the twenty-first century's business environment is considerably enabled by advanced computing, networking, and telecommunications. Business operations are thus significantly impacted by not only the accelerated business globalization but also the increased environmental awareness in societies. By taking advantage of the complex while integrative service interactions involving both providers and customers, emphasis in the service industry has evolved to sources of open innovation, collaboration, integration, and value cocreation, so as to optimally and maximally provide the value (e.g., satisfaction, success, and profitability) for the stakeholders (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7 Value cocreation in focus in the service industry.

The discussions we had so far, including the introduction of service encounters throughout the service lifecycle in Chapter 1, clearly show the people-centric emphasis in phases throughout the lifecycle of service. In other words, we now understand that the value of service is the total perceived value of the outcomes cocreated from a series of service encounters by both providers and customers throughout the service lifecycle. This new round economic wave driven by globalization and services seems getting more sophisticated and dynamic than ever before; there is a need for higher efficiency and better cost-effectiveness in business operations and management across the geographically dispersed value chains.

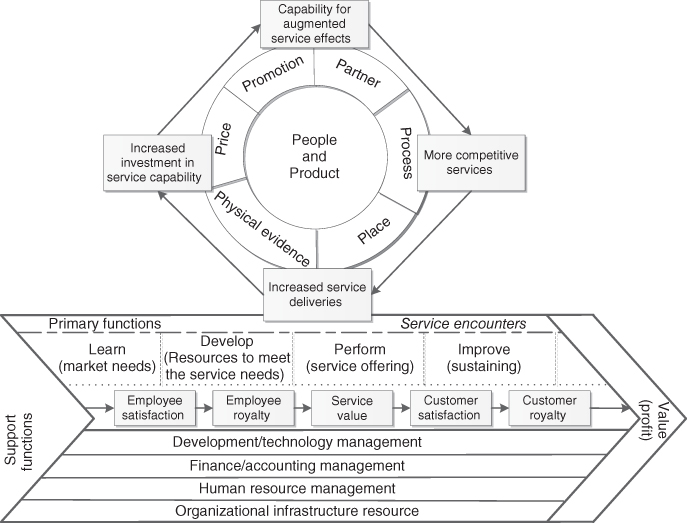

More specifically, the service value (or profit) chain relies on the creation of lifetime customers' experience excellence from well-crafted and fostered service encounters. Figure 2.8 depicts the complex relationships between employee satisfaction, customer retention, and profitability (Heskett et al., (1994); Lovelock and Wirtz, (2007), emphasizing that we must rethink service encounters and find scientific ways to build and manage people-centric, information-enabled, cocreation-oriented, and innovative service organizations in the service-led economy.

Figure 2.8 Competitive service business driven by service-oriented innovations.

As shown in Figures 2.7 and 2.8, both service providers and customers who are value-creating entities on a service value chain are interwoven in the process of service transformation. The highly correlated value-creating relationships between service providers and customers truly become the general characteristics of the modern services, indispensable for the successful completion of the lifecycle of service. By further examining the operational and managerial priority changes in response to the economic shift from manufacture and service (Table 2.1), we understand that the consistent sensing, interaction, and creativity from customers' feedbacks, participations, or consumptions throughout the lifecycle of service play a pivotal role in satisfactorily performing services that customers want (Ahlquist and Saagar, (2013):

- Learn. With the fast development of the Internet and the considerable improvement of living standards and life qualities, our customers have become more knowledgeable and demanding than ever before. For instance, social marketing by leveraging Web 2.0 is crucial for service providers to demonstrate the value of offered services. More importantly, it helps to conceive the concepts of services, know the market trends, engage the prospective customers, and understand customers' changing perceptions in the to-be offered services. In the service industry, hence, discovering and capturing the real and changing needs in a timely manner is what this phase really is about.

- Develop. As compared to focusing on the development of main and unique features and technical functions of physical goods in the traditional manufacturing, the development of services in a competitive service organization must frequently involve customers as the customers might have perceived the needs differently and/or changed the needs as time goes. Quite often, in addition to the technical features and functions embodied in services, service providers' soft resources (i.e., operant resources) should be well developed in order to deliver the services successfully. The development of soft resources in the service organization radically relies on the consistent feedbacks from the customers so that the right soft resources can be developed and made readily available for service delivery. In the service industry, thus, developing competitive services cannot be effectively done if customers are not involved in the development of to-be offered services. Customers significantly contribute to the development of service products. In other words, the value of services is indeed cocreated by both service providers and customers.

- Deliver. This phase in services is substantively different from the one in manufacturing. As soon as physical goods are sold, customers utilize the provided features and functions supported by the physical goods. However, services are being most likely consumed at the same time when they are being delivered. Service encounters are the key delivery mechanisms in the service industry. Successful and satisfactory deliveries of services significantly depend on efficient and effective service interactions between service providers and customers. Once again, the benefits of services are consistently cocreated through collaborative service delivery processes involving both service providers and customers.

- Improve. As discussed earlier, the quality of services is largely influenced and determined by the customers' perceived value, including success, happiness, satisfaction, and the like. The addition of new features and functions mainly used in improving the manufacture of physical goods is insufficient in the service industry. Usually, customers' social, physiological, and psychological roles played throughout the service lifecycle must be analyzed, focusing on the improvement of the resources applied in services and/or the enrichment of service encounters to meet the needs of the customers with continuously increased levels of satisfaction.

2.2 Total Service Lifecycle: The Service Provider's Perspective

Let us briefly recap what we have summarized in Chapter 1 on the general customers' perceptions of services. A service is essentially considered as the “act of performing,” which is a mutually beneficial activity for its provider and customer. Quite often, a service evidently manifests itself as a series of service encounters in the marketplace. The resultant value of service is usually the total perceived value of the outcomes generated from the performance of the formed service encounters chain throughout the service lifecycle.

Simply put, this perceived service by customers clearly implies performing actions. No matter what kind of service product (i.e., in a physical, soft, or hybrid form) is offered, a service with its involved service product gets completely executed only after a series of service encounters are successfully conducted. The real value of the service thus largely depends on when, where, and how the process governing all the relevant service encounter activities are performed from beginning to end and particularly how both service providers and customers have participated in the process execution.

Except for sharing the common concept of service, surely, operating a contemporary and sizable food service business compared to the ancient food service example discussed in Chapter 1 is quite different and becomes extremely more challenging. The marketplace is full of competition in many aspects, including a variety of foods, much leisured and cozier catering settings, knowledgeable clients who have a variety of socioeconomic, social, and cultural backgrounds, and different and changing clients' expectations throughout corresponding catering service processes. Accordingly, the value becomes very challenging to measure as it varies with the service providers, consumers, and marketplaces. Thus, experience-based service business operations can hardly survive in the current and competitive marketplace.

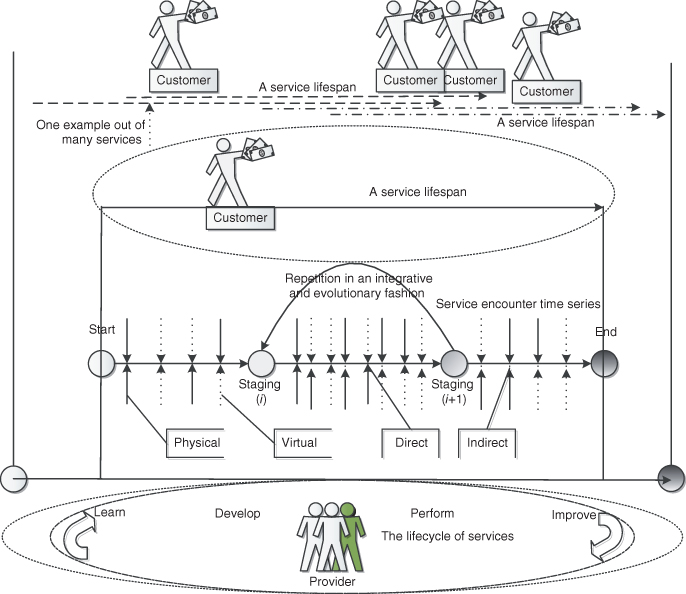

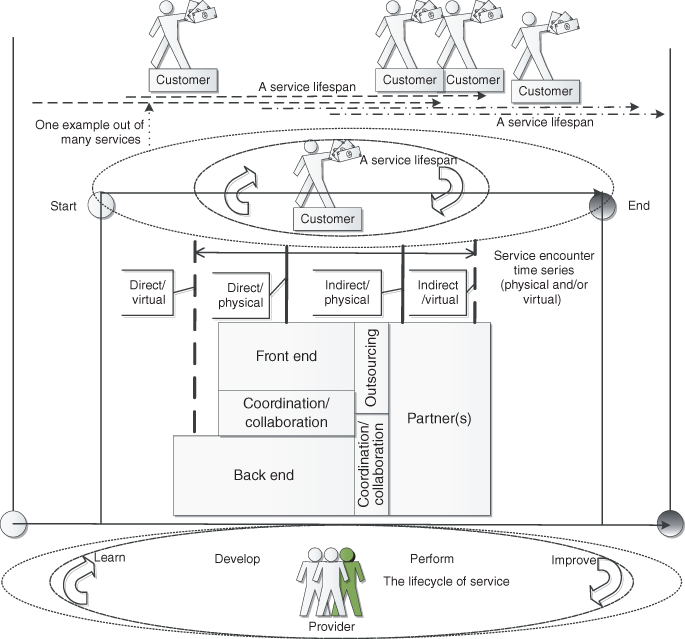

Although the understandings of a service from both service providers and service customers should be the same, we must be aware that the lifecycle of services based on the general customers' perceptions of services are substantively different from one that is conceived, developed, and managed from the service provider's point of view. Figure 2.9 schematically compares the perspectives of service lifecycles from a service provider and a service customer. The lifecycle of service in customers' perspective essentially is just a service lifespan. We can clearly see that the life of a given service from a customer point of view is essentially part of the total service lifecycle operated and managed by the service provider. In a service organization, from the operational and managerial perspective, the lifecycle of service spans over all the phases defined in the service diamond relationship. However, as indicated earlier, frequently a customer's service life mainly lies in the service delivery and operations phase.

Figure 2.9 Perspectives of services: service providers versus service customers.

Let us recap what we just explored. To a typical customer of a service organization, the life of a service offered by the service organization starts when the service is requested and ends when the service is completely performed (Figure 2.9). The corresponding lifespan to the customer is simply a part of the total service lifecycle horizon covered by the service organization. Theoretically, a start point can be anywhere while its end point can also be anywhere as long as the corresponding service lifespan is a positive number. In practice, a start point could be a point after such a point at which the marketed service product is requested by a customer after it becomes ready to be offered by the service organization. Then, a corresponding end point will be the time when the service is completely performed and the specified or default contract period expires.

To a customer, the encounter of a service or “moment of truth” frequently is regarded as the service from the customer's perspective (Bitner et al., (1990); Bitner, (1992). However, a systemic view of service encounters throughout the service lifecycle is necessary for a service provider, which can be created by incorporating the organizational view of service encounters (Figure 1.8) into Figure 2.9, which is illustrated in Figure 2.10. Value cocreation-oriented business processes surely are people-centric, involving both providers and customers in pursuit of excellent user experience and high level job satisfaction.

Figure 2.10 A systemic view of service encounters in the service lifecycle.

As discussed in Chapter 1, this book promotes a new look of service encounters. Instead of focusing on the interacting activities between providers and customers during the process of service deliveries, we explore all the interactive activities between providers and customers, including their interactions from the point of service conceiving to the point of service termination. Consecutive service encounters form a service encounter chain (Svensson, (2004); Qiu, (2013), which can be mathematically modeled as an event-based time series. In a service encounter chain, a later encounter is inevitably influenced by the immediately preceding one; employees or customers could also be influenced by other previous encounters that they may have had before if those are somewhat functionally or sociopsychologically related. Apparently, as a series of service encounters entails mutual benefits in a cascading and integrative manner, we can maximize the benefits only if the cocreation-oriented business processes can be totally, cost-effectively, and efficiently executed.

The earlier discussions further confirm that only effective cocreation-oriented business operations throughout the service lifecycle in service organizations can deliver competitive services in the long run. In this book, in analog to 8Ps that have been widely used in the service marketing field, we would like to use 4Ds hereafter, “Discover,” “Develop,” “Deliver,” and “Do Better,” to describe the fundamental service diamond relationship, aimed at emphasizing the service-dominant instead of goods-dominant logic look of the service diamond relationship in the service industry.

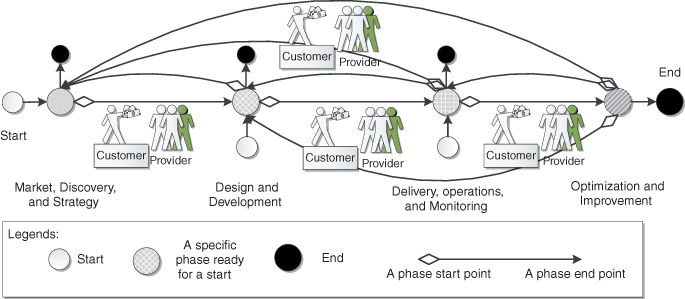

Indeed, the meaning of service lifespan differs when it is viewed from two different perspectives as illustrated in Figures 2.9 and 2.10. This book focuses on the total lifecycle of services from a service organization point of view, aimed at providing a comprehensive understanding of services for service organizations to foster their service business operations, development, and management. When we define the lifecycle of service using the concept of processes, we henceforth adopt four phases or stages to define the milestones of a given service lifecycle. These four stages are “Market, Discovery, and Strategy,” “Design and Development,” “Delivery, Operations, and Monitoring,” and “Optimization and Improvement.” Figure 2.11 presents how the 4Ds cocreation-oriented service diamond relationship can be well aligned with the four-stage service lifecycle across the service business operations, development, and management in service organizations.

Figure 2.11 A 4Ds view of the cocreation-oriented service diamond and process.

Let us use the global project development example that was briefly mentioned in Chapter 1 to show what really consists of service encounters throughout the lifecycle of a given project development service and how varieties of service encounters play critical roles in the fulfillment of the needs of service providers and service customers.

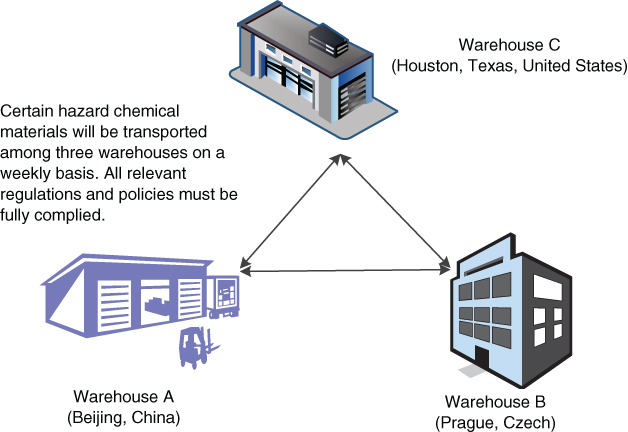

Here comes the project background information. An international chemical company called ChemGlobalService has manufacturing facilities in Houston, United States; Beijing, China; and Prague, Czech across three countries in order to serve its customers across different continents. Each facility has its own warehouse. Each warehouse has its own management system application, which was deployed at different times and thus is unique and user-friendly to local employees (Figure 2.12). The products made at each facility are primarily for serving their individual regional markets to ensure that their business operations are responsive and cost-effective. However, different hazard components that are required by all three facilities are separately made by three facilities. This is due to the fact that some pieces of special equipment are extremely expensive, which essentially prohibits from installing the equipment at each manufacturing site. In addition, certain raw materials are extremely risky and prohibitively expensive to transport. As a result, these hazard chemical components must be transported among three warehouses on a weekly basis.

Figure 2.12 Warehouse application integration across continents.

The global project development group (PDGroup) is a software consulting and development service unit that is formed on a project basis in an international bellwether service organization. ChemGlobalService contracted the PDGroup to help integrate three local warehouse system applications to make sure that the effective and timely coordination among three warehouses is conducted in a collaborative manner. The project's main requirements are summarized as follows:

- Business processes should be defined in support of fully coordinated operational activities within and across warehouses.

- Industry-specific specifications should be supported.

- All environmental protections, treaties, customs, and other related regional and international regulations and policies must be fully complied. Instructions should be provided at the point of need to all the internal and external personnel who are involved in the process of transporting the hazard components.

- User-friendly human interfaces should be provided to warehouse employees. Note that employees in different countries speak different languages and have different educational and cultural backgrounds.

Figure 2.13 Teams with talented people dispersedly populated around the world.

PDGroup as a software consulting and development service unit is hence formed by including six small groups of people. Groups are located in different geographic areas, aimed at leveraging their strengths to meet the project needs. A top-level management unit (i.e., Team A) stays in the New York City (NYC), United States. Team A, consisting of one team manager, one team architect, and one team business analyst, oversees and coordinates the overall project development and deployment across the entire virtual project team. Each of other groups has certain unique skill sets of from 5 to 15 talent employees, including a software designer, a group architect, programmers, quality assurance staff, business analysts, and a group manager. The following list provides the above-mentioned individual group's respective and unique competency (Figure 2.13):

- Team A located at NYC, United States—This team is essentially the administrative team, leading, overseeing, and coordinating the whole project development and deployment across the entire virtual project team.

- Team B located at San Jose, California, United States—This team has a group of persons of talent in human interface design and development.

- Team C located at Houston, Texas, United States—This team has a group of persons of talent in the field of warehouse systems. This team is local and close to the customer facility in Houston, United States. The team will be able to get familiar with the local warehouse system quickly and thus understand local warehouse operations and relevant application and managerial needs.

- Team D located at Prague, The Czech of Republic—Similar to Team C, this team has a group of persons of talent in the field of warehouse systems. This team is local and close to the customer facility in Prague of the Czech of Republic. The team will also be able to get familiar with the warehouse system in Prague quickly and understand local warehouse operations and relevant application and managerial needs.

- Team E located at Beijing, China—Just like Teams C and D, this team has a group of persons of talent in the field of warehouse systems. This team is local and close to the customer facility in Beijing of China. Hence, it will be convenient and easy for the team to get familiar with the customer warehouse system in Beijing and surely understand local warehouse operations and relevant application and managerial needs.

- Team F located at Bengaluru, India—This team is a software outsourcing partner. This team has a group of persons of talent in the field of software design, development, integration, and systems test.

- Team G located at Sydney, Australia—This team has a group of persons of talent in the field of enterprise application integration, business analytics, and international regulation and policy compliance.

Figure 2.14 Cocreation-oriented process in pursuit of a series of positive service encounters.

We briefly summarize how the project can be completed on time by highlighting service encounters necessary throughout the project development service lifecycle (Figure 2.14):

- At the Market Phase. A project draft specification might be brainstormed when the top-level management group meets with a group of customer representatives. The participations of managerial and operational personnel from the organization- and unit-level at different facilities of the ChemGlobalService are necessary. Onsite visits might also be needed, aimed at collecting the requirements from daily business operations and end users' sociopsychological constraints by discussing with the end users.

- At the Design and Development Phase. The project specification will be revised and enriched as time goes. Unless the project is completed, it is typical that the specification will keep changing to some extent. Surely each revision will be the outcome of numerous onsite or virtual meetings among related representatives from the ChemGlobalService and all teams, that is, Team A to Team G. Customer representatives could be directly or indirectly contacted by group members whenever there is a need.

- At the Delivery, Operations, and Monitoring Phase. Most likely, people from Teams A, B, C, D, and E would have to be involved. Before the solution gets fully deployed, PDGroup must make sure that end users will be well trained. Intensive interactions between service providers and customer are necessary during this phase, which ensure that the daily operational needs of end users are fully understood and met. The deployed solution should warrant a twofold success. That is, the daily business operations are well coordinated and monitored among three facilities as expected, while end users' sociopsychological needs are also satisfactorily met.

- At the Optimization Phase. All the teams should be involved to some degree. However, Teams A, B, and G would have more interaction with related representatives from the ChemGlobalService, aimed at understanding the weakness of the deployed solution and ensuring that new additions to the changes meet the needs of business operations in the ChemGlobalService.

In general, we understand that this global project development service surely requires a series of interactions and coordination, physically and/or virtually. Varieties of service encounters throughout the lifecycle of global project development service are collaborative in nature. In theory, the lifecycle of service can be completely described using a service encounter graph, which is graphically illustrated in Figure 2.14. The effectiveness of the provided service highly depends on service encounters that should occur in a timely, efficient, and effective manner.

As indicated in Figure 2.14, a series of service encounters for a given end user or customer representative can start at any point and end at a point after his/her start service initiates. To an end user or customer, such an event-based series of service-oriented interactions essentially constitutes the customer's service lifespan, which largely depends on the role of the end user or customer representative with the ChemGlobalService. In other words, individual's service lifespan varies with his/her role at work. By the same token, a member of the PDGroup, including the personnel at the outsourcing group, will also take a role-based trajectory of a series of service encounters. As a value cocreation service interactive activity, each service encounter makes a difference and contributes to the success of the project development service. To the service provider as a whole (i.e., PDGroup's perspective), the sum of all the series of service encounters essentially creates a service encounter network. The efficacy and effectiveness of planning, design, operations, and management of the service encounter network throughout the service lifecycle will directly impact the value of the provided service. Managing and control of service encounter networks in an optimal way become necessary for service organizations to ensure that all the services will be designed, developed, delivered, and operated to meet the needs of both service providers and customers.

2.3 A Service Definition for this Book

Before we formalize our definition of service for this book, let us recap some noticeable definitions of service we have had over the years. In particular, we pay much attention to the service definitions that substantively reflect the status quos of the developed economy in the twenty-first century. As discussed earlier, to most end users, numerous versions of service definitions have been, more or less, intuitively formed from their changing perspectives of consumed services to meet their work and daily life needs under their respective circumstances. On the basis of the discussions in Chapter 1, three quite popular forms of definitions can be recapped as follows:

- When a service is performed, if the service encounters are largely physical, intensive, and direct from the customer's perspective, service is typically defined as an act of beneficial activity. Examples include commonly consumed services that are provided in the bank and finance, hospitality, tourism, resident education, and health care industries.

- By contrast, when a service is performed, if the service encounters are mainly virtual, brief, and indirect from the customer's perspective, then service is quite often defined as the supplying of utilities, commodities, information, or digitalized media. Popular examples, such as online retailing, e-commerce, communications, online social networking, e-banking, digital libraries, online education, and traditional utilities and distributions, surely belong to this category.

- People take many “public” types of services for granted. These types of services can be indeed public or private, profit or nonprofit. Public services are frequently provided by governmental agencies, federal- or state-funded nonprofit organizations, or profit service organizations that subsidized by the governments. Specific examples can include public transportations, varieties of federal and state licenses, post office, security and customs services, etc.

Although the above-revisited definition examples show the viewpoints of end consumers, they indeed capture one of the key components that rudimentarily describe services, which is the performance or act of performing. It is the act of performing that gradually and cumulatively generates the value of service. From the earlier discussions, we also concluded that service encounters are crucial in the service industry although service encounters might be optional for a manufacturer in the manufacturing industry. In addition, no matter how and what kinds of service encounters occur during service business operations and management, people undoubtedly play a central role in the performed services.

We understand that a significant portion of the services provided by the service industry is consumed by individuals, such as medical, education, insurance, legal, financial, transportation, and retailing services. Recently business services that serve different business units or organizations are growing rapidly. For example, international trades, technical support, enterprise resource planning, call center operations, sales management, IT implementation, e-logistics, and business investment and business transformation consulting are well recognized as highly profitable business services in the twenty-first century (Qiu et al., (2007).

For many years, however, when service research and practices were conducted, physical goods-dominant thinking approaches were mainly taken for granted in academia and practice. In addition, due to the prior lack of the necessary means to monitor, capture, and analyze people's dynamics throughout the service lifecycle, the full exploration of the fundamental service theory and principles was prohibitively expensive. The five core elements identified in Figure 1.2 thus were typically studied in a nonintegrated and nonsynergistic manner although the importance of having systems approaches was fully recognized.

To keep abreast of the fast development of the service-led and globalized economy, many academic scholars and professional practitioners have proposed numerous definitions of service since the beginning of this new millennium. The literature shows that many excellent attempts have been well conducted over the last decade or so, aimed at meeting the needs of their focused fields, respectively.

By exploring the marketing shift from the exchange of tangible resources, embedded value, and transaction-based “goods” to the exchange of intangible resources, the cocreation of value, and relationship-based “service”, the concept of evolving a service-dominant logic in the field of marketing to replace a goods-dominant logic burgeoned at the very beginning of this new millennium. Many service marketing researchers and pioneers emphasize that we should establish the general concepts, worldview, and small set of fundamental propositions about the services of today and in the future. Vargo and Lusch (2004) have comprehensively reviewed the service marketing research literature in the relevant areas and presented the foundational premises of the emerging service marketing paradigm: “(i) skills and knowledge are the fundamental unit of exchange, (ii) indirect exchange masks the fundamental unit of exchange, (iii) goods are distribution mechanisms for service provision, (iv) knowledge is the fundamental source of competitive advantage, (v) all economies are services economies, (vi) the customer is always a coproducer, (vii) the enterprise can only make value propositions, and (viii) a service-centered view is inherently customer oriented and relational.”

Vargo and Lusch (2004) further articulate that the essential concept of “service” should be defined as the application of competences for the benefit of another entity and the term “service” focusing on a process rather than “services” implying “intangible goods” should be used given that the service value is always cocreated during its production. Through further identifying intangibility, heterogeneity, simultaneity, perishability, customer participation, and coproduction (i.e., cocreation) as key commonalities across disparate services businesses, Sampson and Froehle (2006) present the need for a Unifying Services Theory (UST). They particularly argue that the presence of customer dynamic inputs is necessary and sufficient to define a service development process, which is why service processes are typically harder to manage than goods production processes. Their investigation focuses on revealing some principles common to a wide range of services and providing a common ground for further theoretical exploration of capacity and demand management, service quality, service strategy, and so forth.

“A service is the non-material equivalent of a good. Service provision is defined as an economic activity that does not result in ownership, and this is what differentiates it from providing physical goods. It is claimed to be a process that creates benefits by facilitating either a change in customers, a change in their physical possessions, or a change in their intangible assets” (WikiGDPList, (2012). The emergence of the service-dominant logic and cocreation-oriented business process theory makes us rethink service research and practice in general.

Indeed, if we focus on the core difference made due to the economic shift from manufacturing to service, we can surely find that we increasingly emphasize the cocreation-oriented activities between service providers and service consumers throughout the service lifecycle. The disruptive difference compels us to make a considerable change, transforming the way we run service businesses today and in the future. More specifically, people's social, physiological, and psychological capacities identified in Table 2.1, consequently, must be fully understood and incorporated into the lifecycle of service for a service organization to stay competitive. Although physical products might continuously be the core in the manufacturing industry, people-centric service encounters that cocreate service values must become organizational stars in the service industry.

Figure 2.15 A process-driven view of services.

When people-centric and process-driven service encounters are fully incorporated into the five core elements identified in Figure 1.2, we can model a service using the following five core elements (Figure 2.15):

- Resource. Traditionally classified resources are natural, human, and/or manufactured or infrastructural. Service products as a fundamental resource in service provision can be in a physical, nonphysical, or hybrid form. For example, an online iPad retailing is a physical service product, a training course is nonphysical product, and a two-year AT&T wireless plan is a hybrid service product. Essentially, with the help of resources the act of performing a transformation task for a customer who asks for it in exchange for acceptable compensation is termed as service provision. Once again, we emphasize that resources are the conduits of service provision to customers.

- Provider. Service products are offered by service providers. A service provider as an entity can be an individual, group, organization, institution, or governmental agency.

- Customer. Service consumers are human beings who consume, acquire, or utilize the service products offered by their service providers.

- Value. Service providers and customers typically have different value propositions. However, their value propositions should be mutually beneficial. The aggregated benefits cocreated from a service are essentially the service value. The service value for a service provider could be profit, satisfaction, and/or competitiveness. The service value for a service customer might be satisfaction, improved competence, possession, and/or productivity. The value of service is typically accumulated by completing a series of service encounters, always involving both the service provider and the service customer.

- Process. A typical service process starts from the occurrence of the first interaction between a service provider and a service customer, directly or indirectly. It ends when the offered service product is completely phased out from the engagement agreed by both the provider and the customer. When the lifecycle of service is analyzed, four main stages in a service process can be theoretically identified, market, design and development, delivery and monitoring, and optimization. Value cocreation-oriented service encounters should be well designed and conducted throughout the service lifecycle. In practice, the business activities at stages are often executed in a concurrent and coordinated manner once a service process completes its initial cycle. Although the priority of a stage might be changed as time goes, the process cycle progresses repeatedly until the offered service gets completely closed out.

No matter what service is designed, developed, and delivered, whether the service need is fully met and the served customer is completely satisfied currently relies on the efficient, effective, and smart operations of its service-oriented delivery network, fully leveraging the advanced resources empowered by the technology, innovation, and information-enabled processes. Being characterized by digitalization and globalization, a competitive service-oriented delivery network essentially is an integrated and process-driven heterogeneous service system (Figure 2.16). As a service system puts people (customers and employees) rather than physical goods in the center of its organizational structure and operations, the service system is a sociotechnical system (Qiu et al., (2007); Spohrer et al., (2007), focusing on service design, development, and delivery using all available means to realize respective values for both service providers and service customers. More detailed discussion on sociotechnical service systems is provided in later chapters.

Figure 2.16 A sociotechnical process-driven systems view of services.

Since the 1990s, the fast advancement and significant stride in distributed computing and interconnected network has extraordinarily increased the role and power of IT and communications, transforming the ways how the service industry operates (Schaeffer, (2011); Berman, (2012); Drogseth, (2012); Ahlquist and Saagar, (2013). By using service-dominant thinking while leveraging the increased flexibility, responsiveness, and capability of IT-enabled service business operations and management, service organizations can be realistically operated as effective sociotechnical service systems, improving the business operational productivities and delivering new high levels of job and customer satisfaction (Qiu, (2013).

Figure 2.16 indeed captures and illustrates the marrow of most discussions we have had so far, from which we can try to state a definition of service in a conclusive manner. Here is the definition of service for this book:

Service is considered as a transformation process in which both provider-side and customer-side people participate in an interactive manner, applying relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences in order to cocreate mutual benefits for the service providers and their customers. Technically and socio-economically the transformation process encompasses a series of service encounters that can be direct or indirect, consecutive or intermittent, physical or virtual, and brief or intensive. The value of the service depends on the socio-technical efficacy and effectiveness of all of the service encounters experienced throughout the service lifecycle.

Please keep in mind, this definition does not aim at replacing the extant definitions that meet the needs of different research disciplines and business environments in academia and practice. This definition simply is an understanding of service that is interpreted in our perspective, focusing on providing the foundation for us to explore service in a systems and holistic manner in this book. The systems and holistic perspective of service includes the following fundamental understandings:

- A service is viewed as a transformation process that creates sociotechnical effects, delivering the values that are, respectively, beneficial for both service providers and customers.

- A service provision through a transformation process is centered at people rather than products, resulting in that service-dominant thinking must replace goods-dominant thinking in service engineering and management.

- A service provision entity is a sociotechnical service system. It is typical that a competitive service system consists of a number of interrelated and interacted domains systems empowered by a variety of operational resources, which are coordinated in a collaborative manner, regionally and/or internationally.

- The realized value of service is the total perceived value of the quality outcomes cocreated by providers and customers through a series of service encounters throughout the service lifecycle.

Here comes a concise version of the definition of service for this book:

Service is considered as an application of relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences and manifests itself to customers as a service encounter chain that substantively reveals the cocreation of benefits for both service providers and customers.

2.4 Final Remarks

This chapter systematically discussed different perspectives of services, aimed at capturing the marrow of today's services in the information era. We truly understand that service is not just a product. Service is a transformation process in which both provider-side and customer-side people are always involved in an interactive manner. Service is thus an application of relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences, capable of cocreating benefits, respectively, for service providers and customers. As summarized in Chapter 1, a service is people-centric, truly cultural and bilateral. The type and nature of service dictates how a service is performed, which accordingly defines how a series of service encounters could and should occur throughout its service lifecycle. The type, order, frequency, timing, time, efficiency, and effectiveness of the series of service encounters throughout the service lifecycle determine the quality of services perceived by customers who purchase and consume the services (Booms and Bitner, (1981); Bitner; (1992); Chase and Dasu, (2008).

The service business setting has changed substantially. The changes include that (i) more and more data become available, helping to capture the behavior of people and systems dynamics; (ii) service scopes are changing, resulting in that the worldwide competition is essential; (iii) with the help of advanced computing and networking technologies, theories and methodologies can be easily turned into a variety of powerful means that can further empower effective service operations and management to deliver quality services.

In summary, we have defined what service is for this book, laying the foundation for the following chapters of this book. Henceforth in this book, chapter by chapter, different and highly appreciative relationships within service will be further identified and explained in detail along with the discussion of a variety of qualitative and quantitative approaches that should be adopted by service organizations in pursuit of competitive business goals in the service-led economy.

References

- Ahlquist, J., & Saagar, K. (2013). Comprehending the complete customer. Analytics—INFORMS Analytics Magazine, May/June, 36–50.

- Bell, M. (1981). A Matrix Approach to the Classification of Marketing Goods and Services in Marketing of Services, 208–212, ed. by J. H. Donnelly and W. R. George. Chicago: American Marketing.

- Berman, S. (2012). Digital transformation: opportunities to create new business models. Strategy and Leadership, 40(2), 16–24.

- Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: the effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 69–82.

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71.

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. The Journal of Marketing, 54, 71–84.

- Booms, B. H., & Bitner, M. J. (1981). Marketing strategies and organization structures for service firms. Marketing of Services, 47–51.

- Bowen, J. (1990). Development of a taxonomy of services to gain strategic marketing insights. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 18(1), 43–49.

- Chase, R. B., & Dasu, S. (2001). Want to perfect your company's service? Use behavioral science. Harvard Business Review, 79(6), 78–85.

- Chase, R. B., & Dasu, S. (2008). Psychology of the Experience: The Missing Link in Service Science in Service Science, Management and Engineering Education for the 21st Century, 35–40, eds. by B. Hefley and W. Murphy. US: Springer.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2011a). Open Services Innovation: Rethinking Your Business to Grow and Compete in a New Era. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2011b). Bringing open innovation to services. MIT Sloan Management Review, 52(2), 85–90.

- Drogseth, D. (2012). User experience management and business impact—a cornerstone for IT transformation. Enterprise Management Associates Research Report. Retrieved Oct. 10, 2012 from http://www.enterprisemanagement.com/research/asset.php/2311/.

- Heskett, J. L., Jones, T. O., Loveman, G. W., Sasser, W. E., & Schlesinger, L. A. (1994). Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 164–174.

- Karmarkar, U. (2004). Will you survive the services revolution? Harvard Business Review, 82(6), 100–107.

- Lovelock, C. and J. Wirtz, 2007. Service Marketing: People, Technology, Strategy, 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Loveman, G. W. (1998). Employee satisfaction, customer loyalty, and financial performance—an empirical examination of the service profit chain in retail banking. Journal of Service Research, 1(1), 18–31.

- Qiu, R. G. (2013). We must rethink service encounters. Service Science, 5(1), 1–3.

- Qiu, R. G., Fang, Z., Shen, H., & Yu, M. (2007). Editorial: towards service science, engineering and practice. International Journal of Services Operations and Informatics, 2(2), 103–113.

- Rangaswamy, A., & Pal, N. (2005). Service innovation and new service business models: harnessing e-technology for value co-creation. An eBRC White Paper, 2005 Workshop on Service Innovation and New Service Business Models, Penn State.

- Sampson, S., & Froehle, C. (2006). Foundation and implication of a proposed unified services theory. Production and Operations Management, 15(2), 329–343.

- Schaeffer, M. (2011). Capitalizing on the smarter consumer. IBM Institute for Business Value—IBM Global Business Services Executive Report. Retrieved on Dec. 6, 2012 from http://www-935.ibm.com/services/us/gbs/thoughtleadership/ibv-capitalizing-on-the-smarter-consumer.html.

- Schneider, B., & Bowen, D. (2010). Winning the Service Game in Handbook of Service Science, 31–59, eds. by P. Maglio, C. Kieliszewski, and J. Spohrer. US: Springer.

- Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C., Czepiel, J. A., & Gutman, E. G. (1985). A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: the service encounter. The Journal of Marketing, 49(1), 99–111.

- Spohrer, J., Maglio, P., Bailey, J., & Gruhl, D. (2007). Steps toward a science of service systems. Computer, 40(1), 71–77.

- Surprenant, C., & Solomon, M. (1987). Predictability and personalization in the service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 86–96.

- Svensson, G. (2004). A customized construct of sequential service quality in service encounter chains: time, context, and performance threshold. Managing Service Quality, 14(6), 468–475.

- Vargo, S., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17.

- WikiGDPList. (2012). List of Countries by GDP Sector Composition. Wikipedia. Retrieved on Dec. 10, 2012 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_sector_composition.