4

Your Days

![]()

MYTH

Singletasking is unproductive.

REALITY

Singletasking is the most productive way to get things done.

There’s never enough time to do it right, but there’s always enough time to do it over.

JACK BERGMAN

There is an outside possibility that you feel overwhelmed because you can’t seem to get everything done. How do some people manage to get so much accomplished in a day?

The Harvard Business Review reported on the work habits of highly effective employees.1 Besides getting immediately to work upon arrival, these employees also took regular breaks throughout the day. Integrating recharge time into their daily schedule made them more efficient overall. High performers even singletask during lunch—they don’t do work while enjoying their midday meal.

Take note! We accomplish more by allowing pockets of rest time. Engrossing ourselves in tasks when we’re “on” is the other side of the coin. Even so, how do you survive a day with too many demands?

A Day in Your Life

Perhaps you are plagued by unhelpful thoughts such as, “I can’t do it! Ackkk! Save me from drowning in my own to-do list!”

Help has arrived. I spoke with a diverse range of professionals about the types of activities they may hope to complete in a single morning. I compiled a list, removed the specifics for broad application, and put together two ways to tackle this list over the course of a workday morning.

Meet Dave.

Here’s what Dave says he needs to do one morning:

![]() Proofread and send a proposal to a client

Proofread and send a proposal to a client

![]() Attend an internal staff meeting

Attend an internal staff meeting

![]() Give a performance review to a direct report

Give a performance review to a direct report

![]() Participate in a conference call

Participate in a conference call

![]() Get on the chief information officer’s schedule

Get on the chief information officer’s schedule

![]() Respond to or delete 200+ emails

Respond to or delete 200+ emails

![]() Present recommendations to the transition committee

Present recommendations to the transition committee

Also, his wife is giving a big presentation to her main client this morning, and he promised to meet her for lunch near the office at 12:15 p.m.

Take One: An Ever-Expanding Mess

Dave arrives at work and heads to the lunchroom to grab some coffee. Lisa and Ted are there, pulling him into a fifteen-minute conversation about the previous evening’s networking event. They have a few laughs, and he tells himself it is a good way to start the day and build rapport. Plus, he doesn’t want to be rude.

He gets to his office and notices a note on his chair from the new accounting manager, placed there after Dave left work yesterday. Dave needs to fill out data input forms to be included in the upgraded payroll system. Reluctantly, he heads downstairs to take care of it. After all, better now than never.

Back up at his office, his junior staffer, Nelson, is waiting, sitting in the guest chair, armed with a pile of papers. Nelson launches into a diatribe about the incompetent marketing team, dramatically waving a flyer in the air as evidence. Dave half listens while he searches for emails he can mindlessly delete. He wants to be a supportive supervisor, yet he needs to balance that with getting some of his own work done for a change.

Just then, Betty cheerily pops her head in his door to remind him that the staff meeting is about to start. Everyone is assembled down the hall except Dave. He sputters an expletive, grabs his tablet, and follows Betty out the door. At least he got away from Nelson.

Dave abhors staff meetings, so he makes the most of his time by pretending to take notes while actually instant messaging with Ted, seated across the table from him. He also shoots off a couple of emails in response to the hundreds that are continually piling up. At one point Grace, his boss, asks for Dave’s input, but he has no idea what topic is being discussed. He plays it off, saying he’s getting old and his hearing must be going. Finally, the meeting ends.

The day is escaping him. He shoots off a text to his direct report Karissa, saying that he must, again, postpone her annual performance review. He glances over the big proposal due at noon. The conference call begins, but he continues to scan the proposal—he doesn’t have a choice. He hits Send, later realizing that a few dates were inaccurate. He makes a note to shoot off a follow-up email in the afternoon, rectifying the errors, and tosses it atop his perilously looming to-do pile.

He runs upstairs to check with the chief information officer’s executive assistant about whether he can meet this week. He figures it is best done in person. She is busy with a scheduled meeting, so he waits. Suddenly he realizes he missed the window to provide recommendations to the transition committee. He is fifteen minutes late for lunch with his wife, and irritated by his morning.

Take Two: Singletasking Saves the Day

Dave knows he has a packed morning ahead, so he arrives twenty minutes early, grabs a quick coffee from the still-quiet staff kitchen, goes into his office, puts a Post-it note on his shut door that says Under deadline, please refrain from knocking, and spends five minutes organizing his morning’s tasks. He filters out those that are unnecessary. He highlights those that are crucial.

Next, Dave looks for ways to carve out time for key tasks. For instance, he sends a message to Grace explaining that he has mission-critical deadlines this morning and asking if he can just attend the first half of the routine staff meeting. He promises he will be fully present during the time he attends. Dave then quickly emails his recommendations to the transition committee.

He spends the next half hour quietly and carefully proofing his client proposal. He turns off all auditory and visual alerts. He sends the proposal off with confidence and opens his office door.

Dave has scheduled the performance review with his direct report Karissa early, before things get too hectic. When Karissa arrives, Dave joins her on the visitor’s side of his desk—both to build rapport and to separate himself from electronic distractions. Dave tells Karissa the appraisal will only last fifteen minutes, during which time he will give Karissa his full attention. He promises no interruptions.

Suddenly, Nelson descends on the office like a tropical hurricane, ranting about the incompetence of the marketing team. Dave interrupts Nelson’s harangue, pointing out that he is in the middle of a meeting and can’t engage with Nelson at the moment. Dave tells Nelson, in a friendly yet firm tone, to schedule a meeting, and immediately returns to Karissa’s performance review.

Dave stops by the internal staff meeting, afterwards settling into fifteen minutes of responding to, organizing, and deleting emails. He delegates several task requests, forwarding the content to others on his team. He can’t believe how many emails are moved out of his in-box when he is truly focused.

Dave has a few minutes before the conference call, so he phones the chief information officer’s assistant to see if he can schedule a meeting for later in the week. She is busy, and promises to email him later with options for times.

Although he is no fan of conference calls, Dave commits to actively participating. Difficult as it is, he resists the urge to respond to emails and messages while on the call. He can discern when others are not engaged and admittedly finds it unprofessional. When the topic proceeds beyond his realm of contribution, he removes himself from the call. Dave heads out with enough time to pick up flowers for his wife en route to their lunch.

Debrief

Jot down some of the techniques Dave employs in the second version of his morning that might be particularly useful for you. For example, dedicating a mere three to five minutes at the start of each workday to organizing your to-do list can transform your entire day into one that is proactive rather than reactive.

What strategies can you employ in your quest for saner workdays? For example, many of us break into a cold sweat when even contemplating the idea of delegation (read: relinquishing full control). However, delegating is important not only to free up your time but also to professionally develop those who work with you. Also, asking others when they actually need to receive something can save you much strain related to cramming in tasks before they are required.

Your Turn

List what you do for three days. Select three upcoming, more or less typical workdays. Decide upon a handy method to note your actual use of time over this period. Smartphone, notepad, stone tablet and chisel—the choice is all yours.

As you stumble through your day, write down the primary tasks you engaged in throughout. You can scribe from the beginning of your workday. You don’t need to break the day into tiny segments or provide loads of detail. You just want a reality check of where the heck your time goes.

Here’s an example. (If you don’t want to be unduly influenced, skip ahead!)

DAY ONE

|

8:30–9:30 |

Arrived at office, greeted colleagues, made coffee, reviewed emails |

|

9:30–10:30 |

Phone call regarding upcoming industry conference |

|

10:30–11:30 |

Reviewed notes from meeting, surfed the Web |

|

11:30–12:30 |

Lunch with coworker, complained about low office morale |

|

12:30–2:30 |

Department team meeting, total waste of time |

|

2:30–3:15 |

Met with information technology expert to fix computer virus |

|

3:15–3:30 |

Hung out in coffee room |

|

3:30–3:45 |

Phoned school counselor regarding kid’s poor grades |

|

3:45–4:00 |

Stared out the window, wondering how to motivate my kids |

|

4:00–5:00 |

Responded to most urgent emails |

|

5:00–5:30 |

Left voicemails for people I hoped were gone for the day |

Obviously this is purely fictitious, created solely from my imagination. Now do your own on the next three pages.

What techniques worked for you?

Where did you stumble?

What advice would you give a peer wanting to be more productive?

What do you want to do differently tomorrow?

Also keep in mind this helpful, if irksome, rule of thumb: If there is a pressing, daunting task you are tempted to avoid, do it as early in the day as possible. Bite the bullet! Tough love, baby. Putting off a crucial task can weigh heavily on your mind, making singletasking on everything else much more difficult.

Clustertasking

What are related groups of tasks that you might do several times during an average workday? A few of my own examples include reading and responding to messages, taking items (articles, papers to sign, letters to mail) to other offices in my building, returning phone calls, and scheduling interviews.

To use this clustertasking technique, identify similar tasks. Group them together into a few combined segments during the day rather than allowing the same types of activities to constantly interrupt your train of thought.

Clustertasking saves time. Some tips for success:

![]() Clustertask during the times of day you’re most alert.

Clustertask during the times of day you’re most alert.

![]() Do like tasks in clusters one to three times a day.

Do like tasks in clusters one to three times a day.

![]() Decide how long you will clustertask and set an alarm to remind you when to stop.

Decide how long you will clustertask and set an alarm to remind you when to stop.

![]() Avoid engaging in these tasks outside of the designated time.

Avoid engaging in these tasks outside of the designated time.

Are you perilously distracted by texts and emails throughout the day? Does social media lure you away from bigger tasks, to the detriment of impending projects? If so, perhaps you will decide to try clustertasking. Begin by confining messaging to three twenty-minute segments during the day: upon arrival, preceding lunch, and before heading out.

You are skeptical. Don’t people have the expectation that messages will be returned more expediently? I am not suggesting that you reply to emails once a week. Three times a day is reasonable.

In addition, many email strings are unnecessarily lengthy because of the frequency of back-and-forth communication. Conversation chains can be eliminated or cut shorter by saying, for example:

![]() No need to reply.

No need to reply.

![]() Thanks, signing off for the day.

Thanks, signing off for the day.

![]() Only respond if there is a change.

Only respond if there is a change.

![]() [Colleague] can handle it, no need to cc me.

[Colleague] can handle it, no need to cc me.

![]() Great. See you then.

Great. See you then.

![]() I’m off-line for the next couple of hours.

I’m off-line for the next couple of hours.

![]() Contact [Colleague] for arrangements.

Contact [Colleague] for arrangements.

Doing this prevents future emergencies. Even on days when I have an intense deadline, for instance, I always start my day with designated time to review my schedule and plow through messages that have accumulated since the day before.

Let’s say you have been out of the office for a few days and return to a landslide of demands in the form of messages, papers, and blinking lights. Don’t panic. I have a system for this very situation. I call it 1 × 10 × 1, and it’s a variation on clustertasking.

Do an initial sweep of your awaiting demands and immediately handle any that can be addressed in one minute or less. This might include a quick email reply, signing off on a project, returning a voice mail, or answering a scheduling request. Next, handle tasks that can be completed in less than ten minutes. Address this group as early in the day as possible. The remaining requests are those that take up to an hour of your time. Integrate these into your schedule over the next few days.

It is best to whiz through as much as possible in the morning, before the office fills with activity.

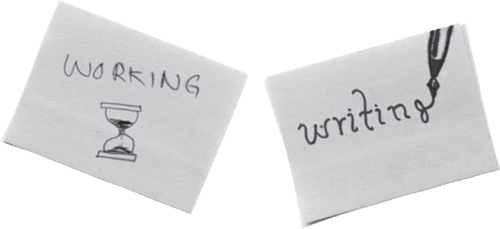

Post-it

The humble Post-it note is your first line of defense. Whether you’re at the helm of an office with a working door, in a cubicle, or at a desk in a mod open floor plan, Post-its are your friends. Write your intention on a Post-it and place on the door, at the entry, or on the edge of your desk.

Observe a couple of sample Post-its my clients made to alert others that they are occupied. Humor and lightheartedness helps. Artistic ability is purely optional.

This does not make you off-limits indefinitely. The longest time frame to be unavailable maxes out at about ninety minutes. It is best to limit the length of your intensive singletasking sessions anyway, stopping before you burn out. You will be more productive and more enthusiastic about the task.

You can helpfully write the end time on your Post-it, such as Please return after 1:30 p.m.!

All interruptions are not created equal. There’s a difference between being unavailable to shoot the breeze and not helping out during a time of real need.

I am against the acclaimed open-door policy, which presupposes interruptions are welcome and expected. For the uninitiated, an open-door policy means that your (real or metaphorical) door is open to unplanned visitors constantly. You are magically available at all times to all people. In reality, this is impossible. Being available to everyone all the time means being present for no one, ever. After all, if I’m in your office and Ray cruises in for a convo, how are you truly available for either of us? You aren’t, and thus you waste everyone’s time.

Make a sign-up sheet on your online calendar or at your office entry point, stating your office hours. Yes, people really do this. And it works.

Your Schedule

When you create a work schedule for your weekly obligations, include at least two open half-hour blocks of time each day to clustertask and to be available for unexpected events. I call this flextime. It requires discipline, but I’ve seen this system in place for even the busiest senior executives. A schedule of back-to-back meetings sets you up to fall hopelessly behind. You can also use open times to singletask toward completion of long-term projects. Consider “unscheduled” blocks to be real appointments that can’t be double-booked unless something urgent pops up. That is part of the purpose of building flextime into the day.

Adopt the approach of a family practice doctor’s office. If you want an appointment for a nonurgent basic annual exam, you may be told the next appointment is a month from today. However, if you call at 8:00 a.m. with a fever and dizziness, they offer an appointment that morning. This is because internists leave openings in their schedules for emergencies.

For a busy professional, this is an ideal model. You don’t need to drop everything for a chatty coworker. Yet, if your schedule is blocked solid, you won’t be available for unanticipated calamities that are bound to arise.

What about loiterers—people who cruise by your office randomly and regularly with no clear agenda or intention to depart? Or let’s say you are housed in an open office, without any borders at all?

I’ve got you covered. Singletasking does not rely on a dream backdrop. A loiterer deposits himself at your doorstep. He is bubbling over with information about his latest fantasy football draft pick. You are under deadline. You respond by:

![]() Glancing up, noting that you’re swamped, and looking back down

Glancing up, noting that you’re swamped, and looking back down

![]() Smiling and pointing at headphones, used to deter unwanted conversation

Smiling and pointing at headphones, used to deter unwanted conversation

![]() Responding, “That’s cool. I’ve got a lot on my plate,” and returning to your work

Responding, “That’s cool. I’ve got a lot on my plate,” and returning to your work

The reality is that the list of what you can do or say to stave off wanderers is endless. You just need to do it. A pleasant expression and a warm smile while delivering the news that you are not available to engage in small talk goes far.

Some folks in an open office plan lament that singletasking is impossible. After all, distractions abound and boundaries are absent. Do not despair. Committed singletaskers have a stronger ability to block out distractions than those who regularly task-switch.2

Singletasking requires dedication and personal accountability. We cannot require an idyllic environment in order to single-task. We cannot place ourselves at the whim of people and events swirling around us. If there is a lot of conversation around you, invest in a white noise machine. They cost next to nothing and last for years. And when you achieve a flow state, external distractions don’t penetrate.3

What about those days when you’re just not able to channel your highest powers of concentration? Most open offices include a few quiet rooms. Use them if needed.

Putting systems in place mitigates interruptions while letting people know your momentary retreat is purposeful and temporary. People appreciate information about your schedule, and as an extra advantage, you will receive fewer nonurgent messages.

Demonstrate attentiveness by being conscientious about letting people know when they can expect to hear back—and make sure you follow through. Remember to restore your voice mail and email autoresponses to your regular outgoing messages. This is far more effective and respectful than attempting to be available when you’re really not.

Practice, Practice, Practice

Singletasking is a learned habit. Select one way to enhance your ability to singletask. Pick something concrete, such as managing unscheduled visitors, turning off social media, designating time to plan each day, remaining focused in meetings, or clustertasking emails. Note each day that you demonstrate your desired behavior (table 3). Success four days a week is a victory. Reward yourself after fifteen workdays—beyond the inherent reward of improving your ability to be in the present moment.

TABLE 3: Noting Days of Desired Behavior

Many of the examples provided are standard workplace scenarios. However the concepts are transferable to any context in which you have many responsibilities, whether you are a freelancer, a student, an artist, or a stay-at-home parent.