7.

NEW NETWORKS AND DECENTRALISED TECHNOLOGIES

‘Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn't really do it, they just saw something.’ These were the words of the co-founder of Apple, Steve Jobs, in an interview in Wired magazine in 1995. As far as I'm concerned, he was right. It is almost impossible to find any innovation that does not essentially combine elements that existed before. The same is also true of life, for example. There are only 118 different chemical elements, all of which are made of helium and hydrogen, but the atoms form the building blocks for our estimated 8.5 million living species (plus an astronomical number of different bacteria and viruses).

That is why the ability and the opportunity to combine things in new ways is crucial to the creation of innovation and thus prosperity. This is also evident in the fact that, historically speaking, prosperity was chiefly created where access to trade was easiest. Until the invention of roads, railways, and air transport, this generally meant in the vicinity of sea and rivers. Accordingly, empire upon empire (for example, the Venetian) evolved from people who had particularly good access to shipping. Probably the most advanced civilisation in Africa emerged on the banks of the only African river that was navigable throughout the year and ran into the sea: the Nile.

In other words, it is all about networking, and connecting people so they can combine their ideas, products, and services – not forgetting genes. And one of the greatest societal changes I have experienced in my own life is a huge increase in the possibilities of communicating with others, of course primarily through the Internet. However, now and in the future, there will be a number of processes related to the Internet that will create totally new dynamics and new opportunities. We're talking new forms of networking, new managerial structures, and new decentralised technologies. Let's take a look at them.

Geosocialisation. Who – and where! – you are

When I am stupid enough to drive to Zurich airport during the rush hour, my GPS sometimes sends me on a detour to avoid traffic jams. It combines knowledge about where I am and where I am going and traffic information, which means that I make my flight, despite traffic jams. But the knowledge of where you are can also be used for geosocialisation, or geosocial networking, in which people get together, according to where they are in purely physical terms here and now. For example, your smartphone might tell you which of your friends and acquaintances are in your immediate vicinity, whether you are near a shop that stocks a product you are after, or whether some of your friends have signed up for an event near your home. Professionally, one of the most interesting aspects of geosocialisation is the fact that it might enhance your understanding of who the people you are surrounded by at professional meetings, conferences, etc., really are and perhaps what they are looking for.

An early example of geosocialisation is the search engine Layar, which combines GPS, a smartphone, and a compass to identify where you are and what you are looking at. The information can immediately be used as a basis for our aforementioned augmented reality.

Synergy between geosocialisation and augmented reality

In order for geosocialisation to become useful rather than annoying or even dangerous, we must each be able to control whom and what we get information about. For example, only two people who both want to know whether the other is nearby, or both want to know about the other's interest in a specific area, should get the information.

The e-commerce revolution – far from over

One particular hallmark of recent years has been the struggle of physical shops to survive in the face of online shopping. Growth in the field of order-based, online shopping is huge. Dominated, particularly in the United States and substantially in other Western countries, by the giant Amazon, in 2018 it exceeded a market capitalisation level of more than $1000 billion.

Physical versus digital commerce in the United States

Online shopping saves time and makes it easier to find and compare the right products than in a physical shop. It also provides access to far more products. For example, Amazon sells more than 10 million different products, plus others from its 200 000 or so Amazon Marketplace dealers. However, e-commerce has a further advantage over physical commerce. In a department store, my shopping basket will reveal whether I have roughly the same lifestyle and taste as you. If I do, we could probably have a useful chat about products we have found and like. But that does not happen, because we do not chat to strangers in department stores, and we do not share our knowledge.

But something similar does, when we shop online via the electronically generated feature: ‘Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought . . .’ In these networks you do not find out who the other people are, but you do learn from each other's experience. By the way, this is known as ‘collaborative filtering’.

However, by leaps and bounds, Amazon is now entering the world of physical retail – a process that began when they acquired Whole Foods in 2017 for just under $14 billion. Obviously, Amazon's approach to physical retail will not simply be the same as that of its rivals, and that may mean moving towards a range of hybrid offers. For example, you order online but pick up your goods in physical shops. That is relevant if, say, you cannot get large packages delivered directly to your home.

One of Amazon's goals is also to create almost fully automated physical shops, where you can just take goods away, after which the money is automatically charged to your account electronically. This can be done via video surveillance and an ingenious combination of IoT, big data, and AI. Amazon has also patented a mirror, in which, via AR, you can see yourself wearing different clothes. The chain Sephora has done something similar. Via Modiface software, their customers can see simulations of themselves in different makeup.

Synergies in e-shopping

One consequence of this development is a new, interesting, and decentralised computer system that includes the so-called ‘physical cookie’. The system takes its name from the online version of cookies, in which our digital footprints are used to target advertising at us. The physical version uses a chip with an isolated computer system, in which the user's behaviour in the shop is tracked. That facilitates the targeting of information for users.

Influencer marketing

Using influencers is a very old strategy in marketing: for example, via product placement in feature films (such as sponsoring James Bond's car) or using brand ambassadors such as Caroline Wozniaki, Tiger Woods, and Tom Cruise. Obviously that phenomenon will not disappear, but it will change. For example, using electronics you can control individually which product placements each user sees. You can also do it with virtual advertisements in live sports TV. However, a large growth area is influencer marketing: where, say, you get networks of popular bloggers to write about your product. It started by focusing on the biggest online stars, but in the future digital algorithms will increasingly be used to detect much broader networks of so-called micro influencers, who are normal people around you rather than online stars. This facilitates the promotion of products that appeal to even the most weird and geeky areas of interest. However, the really major effect is that micro influencers can be more effective, since we rely mostly on our friends and family. That is why companies are already using, and will increasingly use, what really are just average social media users.

The wild decentralised autonomous organisations

A concept that is really useful to know going forward is decentralised autonomous organisations, or DAOs. A DAO is a value-driven organisation that can run totally without management and, in principle, indefinitely, after the founders have left the helm. One version, by the way, is a decentralised autonomous corporation (DAC): in other words, a self-governing company.

An example of something quite like a DAO is Protestantism. Excuse me? No, really. Protestantism resembles a DAO in that, unlike, say, the Roman Catholic Church or Tibetan Buddhism, it has no Pope or Dalai Lama at the top. And yet, while Protestantism has no central top management, it organises and promotes itself relatively spontaneously. Similarly, and again spontaneously, it has often divided itself into subspecies such as Presbyterianism, Baptist, Quakers, and hundreds of other offshoots.

We can also describe the Internet as a partial DAO, although it requires some central control – particularly when it comes to the allocation of domains. But otherwise, the Internet spread globally and to all sectors with neither a plan nor control – almost like a virus. In addition, the Internet is partly a so-called network without infrastructure (NWI), given that it utilises all existing lines of communication. But it is not entirely a DAO and an NWI.

Natural life, however, is a mega-scale DAO. Perhaps with us an exception due to our consciousness of ourselves, life is controlled by the codes in DNA, which is the ultimate DAO, apart from when humans manipulate it. And each of the millions of species on Earth, like Protestantism, manages to organise and promote itself spontaneously, and to divide into new versions, creating spontaneous ecosystems with no top management.

Many recent ‘super firms’ such as YouTube, Uber, and AliBaba are in fact hybrids of traditional companies and DAOs, because a large part of these companies’ assets are created in a decentralised, digital community, which is capable of continuing even if the companies’ management take 12 months off.

We need to be aware that modern DAOs are predominantly digital and controlled by distributed software. These organisations can be very stable because they are not controlled from headquarters. Instead, they are distributed from people's computers around the world – and on each computer the entire company is often available. Malicious examples are computer viruses, which can often function completely without central control, and which also, like biological viruses, can be difficult to eradicate, once they are released. Another and more useful example is Orchid, which makes peer-to-peer Internet that bypasses all routers and thus allows free communication between people living in countries that have Internet censorship. And of course, I have to mention blockchain: the technological premise for the likes of cryptocurrencies. We'll come back to that. But overall, the following applies:

- As the world becomes more digitised, it creates increasing numbers of digital organisations and companies, which can be run and evolve without any form of classic/central management.

The reason for this is, of course, that everything that is programmable can be programmed to perform automatic routines and, thereby, self-management. In principle, a DAO can also be programmed by AI, which would – or will – create spontaneous digital evolution.

Blockchain – the Internet of Value

Blockchain is an important technology for DAOs. It was invented and launched in 2009 by a person (or group) known by the supposed alias of Satoshi Nakamoto. His white paper on the idea relates to Bitcoin (written with a lower case ‘b’ when it refers to currency and an upper case ‘B’ when discussing the network), but the underlying technology is blockchain, which is also Satoshi's invention.

But what exactly is blockchain? It may be defined as a common register for recording a transaction history, which cannot be deleted or altered. Key components are:

- All parties must give their consensus before a new transaction is added to the network.

- A common register, which is impossible to manipulate. Once recorded, transactions cannot be changed.

- This eliminates or reduces paper processes, accelerates transaction times, and increases efficiency.

The first blockchain implementation was digital money, led by bitcoin, and overall its value rose from virtually $0 to $9 billion in May 2016 (which in itself was remarkable) and then to $420 billion at some point in 2018, which was gigantic and obviously dominated numerous front pages. In other words, there was no lack of interest.

It is no wonder that cryptocurrencies have evolved so rapidly. I mean, issuing your own money is a smart business model if it works. Who wouldn't want to own a central bank, ha ha?

Internet of Value

In simple terms, blockchain can also be described as a decentralised technology for recording and booking transfers of value or knowledge of them, without the data being hacked or altered. This can be used to create programmable money, securities, and contracts.

Cryptocurrencies have been criticised for the fact that they in particular have no value in themselves. But that is something of a misunderstanding, because the value lies in the network effect that follows Metcalfe's Law, which states that the effect of a telecommunications network is proportionate to the square of the number of registered users linked to the system.

Paper money works despite having zero intrinsic value, and the same can thus apply to blockchain. Today, blockchain technology can serve as a bookkeeping system, in which value such as money, music, bonds, gift vouchers, bonus points, and shares can be safeguarded. It means that people all over the world can perform peer-to-peer deals without an intermediary, without knowing each other, and without using any security other than that which the blockchain system provides by protecting information with cryptography, complex coding, and a decentralised register.

Decentralised applications and smart contracts

Together, this explains blockchain's ability to facilitate DAOs. The prospect can be explained as follows. It knows no bounds, in the same way that Airbnb allows everyone to rent directly to each other across borders, and it creates programmability in these values, just as your smartphone today has lots of apps – unlike the phone you had in 2005. In this context we refer to ‘dapps’, which stands for ‘decentralised applications’, which correspond to value units with programmed properties. Dapps can also be described as smart contracts, in which an algorithm can determine whether a given contract's content is being complied with, and then reward or sanction financially through blockchain technology, where the process will take place as a regular transaction.

The technology has a myriad of applications, such as a payment for shipping a container that is automatically triggered when a GPS sensor detects that it has arrived at a given location. It can also be used for so-called ‘self-sovereign identity’, whereby people can prove their personal rights without simultaneously revealing their other identity. Provisionally, the most prominent example of the use of blockchain technology is, as mentioned, cryptocurrencies, which can be programmed. A variation of this could be money that is only used in certain businesses, at certain times, or in certain circumstances – something occasionally referred to as ‘coloured money’. It will also be possible to use perishable cryptocurrencies to counteract an economic downturn: for example, by issuing money that can only be used over the next six months, or when interest rates are negative so that the value will turn to dust in your hands unless you spend the money. You could even issue perishable coloured money in order to help a specific struggling sector of the economy during a specific time period. In other words, the technology has the potential to just about eliminate recessions. Imagine that everyone could have a crypto wallet on their smartphone. When a recession is about to start, the central bank would send them some easily perishable crypto money. That should certainly get the ball rolling.

Initial coin offerings

Blockchain is also the basis for so-called ICOs or initial coin offerings, sometimes also referred to as ‘token sales’. It is a bit like stock market listings, but happens outside the usual institutions, and investors pay usually, but not always, with a cryptocurrency such as bitcoin. There are four types of ICO:

- Money: pure currency such as bitcoin or Ethereum.

- Gift voucher: a utility token/user token, which gives buyers access to a service.

- Stocks or shares: equity security, which gives buyers a share in an asset, such as a commodity or an operating company. This can be related to distribution of dividends.

- Bonds: debt allocation that gives access to returns.

In recent years, Nordic Eye and I have been bombarded with ICO offers. It is not something we have invested much time in, since we, and I personally, believe that an overwhelming majority of early ICOs will fail: some because they are simply fraudulent; and others because they are pretty frivolous. Also, partly because most start-ups simply fail. However, the most insightful observers of cryptocurrencies expect that, in most cases, these will just be teething problems for the sector, that the level of quality will rapidly improve, and that blockchain will spread to a variety of sectors. As I write, Facebook has announced its launch of a cryptocurrency which kind of sounds like a big deal for the sector. Wallmart too.

Blockchain can also help reduce poverty. Some 70% of landowners worldwide have only poorly publicly registered ownership of the land or property they actually have at their disposal. In virtually all countries, it is the state that registers land ownership, but in countries where the level of corruption is high, it often happens that property is stolen/redistributed without the actual owner being able to do anything about it.

Many experts believe that the lack of opportunity to register property is one of the major reasons that some nations do not extricate themselves from poverty: partly because people cannot provide security for loans to start a business or give their children a better education. This can be solved by using a separate blockchain system to archive all the information that states normally handle. That would prevent any public administration exploiting its citizens for its own gain.

Here is another example of social benefits. The largest capital outflow from the industrialised world to developing countries consists of private money transactions, estimated at approximately $600 billion per year. This is often people sending money to their families. As a rule, there is a fee of about 10%, and it can take up to six weeks before the money arrives. However, with the crypto-transfer app Abra, the same process can be completed in two minutes at a cost of 2%.

A third potential gain is in industries where individuals are underpaid for the digital content they produce. The music industry is a prime example. Today, songwriters and artistes are paid a mere fraction of the revenue that a hit single generates. The innovative music collective Mycelia is attempting to tackle this problem by linking musicians’ songs to a blockchain, where you can only use the rights to the music if you own them in the block chain. If such projects succeed, it will be significantly more difficult to illegally distribute and share the pieces of music, films, and e-books that are covered: being able to enjoy the artistic content will require direct ownership. And this is an example of one of the most interesting potentials of blockchain: by eliminating middlemen – or at least reducing the need for them – it can spread rewards more efficiently to the people who create the actual value.

The rating economy – good for markets and culture

As is clear from what has been said here, in many of its applications blockchain is a kind of DAO, making, for example, tokens of value programmable, and solving a huge problem vis-à-vis trust between traders who do not know each other's identity. But what to do if they actually know the identity of the other person to some extent, but cannot necessarily expect to trade again?

That is an interesting problem. One of the important features of pre-industrial societies was the fact that you knew your suppliers and used them repeatedly, which meant that providing a good service was very much in suppliers’ own interests, as pointed out eloquently by Adam Smith. What was the point of a blacksmith delivering a poor ploughshare for his neighbour across the lane, when it would be staring him in the face for the rest of his life?

However, as industrial production methods gained ground, and extreme specialisation and division of labour followed, anonymisation evolved, in which we ceased to know the people who made our things. This created bigger opportunities for fooling people.

The trademark or the brand became the solution.

Now, however, the situation has changed again. Thanks to social recommendations and collaborative filtering, we have access to precisely the products that are most likely to suits our needs, and we have access to an endless number of often very sincere assessments of a product's quality.

And that has its consequences. Indeed, with the growing spread of social recommendations and collaborative filtering, retailers are able to remove the trademark rights of some of the manufacturers – distributors instead introduce their own brands or ‘brand-free’ products, also known as white label, at lower prices for consumers and yet greater profit for the retailer. That is possible thanks to the new transparency. Yes, Louis Vuitton or Hermès will still have strong brands, but if you make toothpaste or nappies, it will be harder.

Ratings reflect a network (often anonymous) that streamlines our markets. And they come in many shapes and sizes. In the technology sector, headhunters sometimes use ‘stack overflow ratings’ to assess applicants. This stack overflow shows how often applicants’ replies on technical social media have been upvoted to the best on the Internet. In other words, it is a kind of rating, the importance of which job applicants are probably not always aware of.

On average, the evaluations made by people, who broadly speaking have no motive to write false reviews, are very credible. The evaluations are also a crucial component of the sharing economy, not to mention a significant explanation for the fact that a service like Uber can function and provide better service than a traditional taxi company. Both parties in this transaction know that if the driver treats the passenger badly, he or she will get a bad rating and will therefore be deselected by other potential passengers or totally excluded from the network. Of course, it cuts both ways. The driver also rates the passenger.

The global village and its new cyber rock stars

The spread of the Internet means that a completely new, radical transparency is emerging, which is extremely meritocratic. If you live in a small village in eastern Angola and are really good at football, the whole world can spot your skills on social media – as long as you can film those skills and upload the film online. That was not possible before. Similarly, YouTubers quickly get a very large audience if what they offer is actually interesting and gets upvoted. The fact that the most talented and most dedicated people are discovered is a beautiful and just thought, and it certainly benefits society as a whole. A simple example of that benefit is that appalling restaurants seem to be getting fewer, because now they quickly get blacklisted on social media and lose their customers. And great ones gain fame quickly.

Thanks to rating technologies, over time it will be far more socioeconomically preferable for abilities and effort, rather than advertising budget, social status, personal network, origin, brand, or a particular surname, to determine how well you get on. And over time, it will more often be your customers’ assessments rather than your formal education, family name, or trade union's demands that determine your personal income.

But it goes further than that. In itself, market economics, by experience, creates a more friendly culture, because people have to be good at attracting customers – and even more so if ratings are efficient. We can expect the rating economy to enhance this and to strengthen what is called social capital.

Another effect of this is that it counteracts traditional inflation in goods and services – simply because any buyer anywhere can easily find the cheapest supplier of anything, anywhere on the net. The result is that when central banks change money supply in order to change inflation rates, the effects are often more clearly felt in asset prices than in prices of normal products and services.

Share, care, and save (sharing economy) – hot, hot, hot

There is nothing new about sharing things, but because of IT, it can now be done to a much greater extent than before; and this is an area our venture fund Nordic Eye has invested heavily in by purchasing shares in sharing services for boats, bicycles, storage space, and motor scooters. The sharing economy has become one of the world's fastest growing segments, partly because it often reuses things that already exist. Its main purpose is to save money and resources, while increasing the supply of services by sharing things. There are three forms:

- As-a-service: flexible short-term rental of or subscription to objects or services that a central provider owns and looks after. Examples include server parks in the cloud or scooter rental in big cities. Then there are as-a-service subscriptions, for example, for socks, coffee, or beauty products, which can then normally be sold at reduced prices, because, following the initial sale, the manufacturer acquires a regular customer.

- Crowdsourcing: the same, but here the person in the street owns the leased objects or provides the relevant services. Uber and Airbnb are prime examples. What gets shared can be money, services, or, for example, cars, bicycles, scooters, and motor scooters.

- Peer-to-peer: the person in the street exchanges services without an intermediary: for example, over a DAO, which is not owned by anyone. In this context, ratings are usually required for things to run optimally. Cryptocurrencies, for example, are traded in peer-to-peer networks. But other examples include: Open Garden, where people are connected on the Internet via wi-fi and Bluetooth; Infin, which is a file-sharing application for digital artists; and WebTorrent, which is an anonymous streaming service.

Platforms such as Airbnb are sometimes referred to as peer-to-peer, but actually they are not really, because there is an intermediary involved. However, organised peer-to-peer networks, a kind of hybrid, are frequently the most efficient. Another rapidly growing example is ‘cloud kitchens’ or ‘ghost restaurants’, which solely serve online orders. In their ultimate crowdsourcing form, these can offer freelance chefs the use of the facilities to service online customers.

The synergies of the sharing economy

Amazingly, digital platforms facilitate sharing with the entire world. Previously, only your closest friends knew that you had empty seats in your car on Friday when driving from one city to another. Or that you wanted to share your lawnmower to get part of it paid for by others. Or that you were willing to remove people's garden rubbish on Thursday morning for a small fee. Or that you had a dog that needed walking. Or that you would like to share an evening meal with a family in Barcelona on Saturday. Or that you needed to collect a package at the post office and could take something else with you.

However, this is no longer the case; now you can share such desires – there are markets for them. In fact, you can now offer and request all the above-mentioned services and a huge range of others digitally, to/from a potentially global audience. It is both easy and user-friendly. It even relates to services that would not previously have been sold or shared.

The astonishing thing to many people is that overall you can totally rely on people. When you use Airbnb, eBay, Uber, BlaBlaCar, Lyft, La Ruche qui dit Oui, Munchery, Postmates, and many other of the countless digital platforms, you discover that, in general, people do stick to the agreements that have been made. In this sense, too, I believe that the sharing economy and its ratings improve culture:

- The sharing economy creates increasing trust among humans and thus increases the level of social capital.

The absence of trust is an expensive barrier in all societies. Without trust, we are reluctant to enter into agreements with strangers, and if we do, we invest many, non-value-creating resources in trying to ensure that we do not get cheated.

Arun Sundararajan, an expert in the sharing economy and author of the book The Sharing Economy (2016), has pointed out that, historically speaking, there are some fascinating aspects to the sharing economy. One might immediately believe that the sharing economy yielded less growth, since fewer lawnmowers are needed if 20 people share each of them. Sundararajan, however, argues convincingly that the development will actually increase the economic growth rate. Historically, increased supply, increased variety, and better utilisation of existing resources actually lead to higher per capita productivity; and this higher productivity is a fundamental ingredient of economic growth, to which we can then add the positive effects of increased confidence. He says that this mechanism is stronger than the effect of not producing as many lawnmowers, because people are sharing them. And it is probably underestimated in statistical measurements by national economists, who will certainly detect how many lawnmowers get manufactured but not necessarily what benefit each of them generates. The GDP, which is interesting is the overall benefit or ‘utility’ that it reflects. The sharing economy can help with that. A lot, in fact.

Exponential organisations: big money!

I will round off this review of new forms of networking with a fascinating phenomenon common to many new networks: exponential organisations (ExOs) – a phenomenon which my venture capital colleagues and I love. I have already mentioned a number of examples, including various social networks and crowdsourcing organisations, but their common denominator is that they roll out their services across existing resources (such as the existing telephone network or the existing vehicle fleet) and activate people who are not officially affiliated with the organisation. Uber, Facebook, and Fiverr are examples of utilising existing, available capacity. ExOs often use automation and viral online marketing, and usually have enormous influence on the size of their organisation. Furthermore, they will frequently achieve network effects that can make them very robust, once they have a good foothold. By the way, a classic example is Tupperware, which was founded in 1942 and is a multi-level marketing organisation. Today they have – wait for it – 1.9 million sellers!

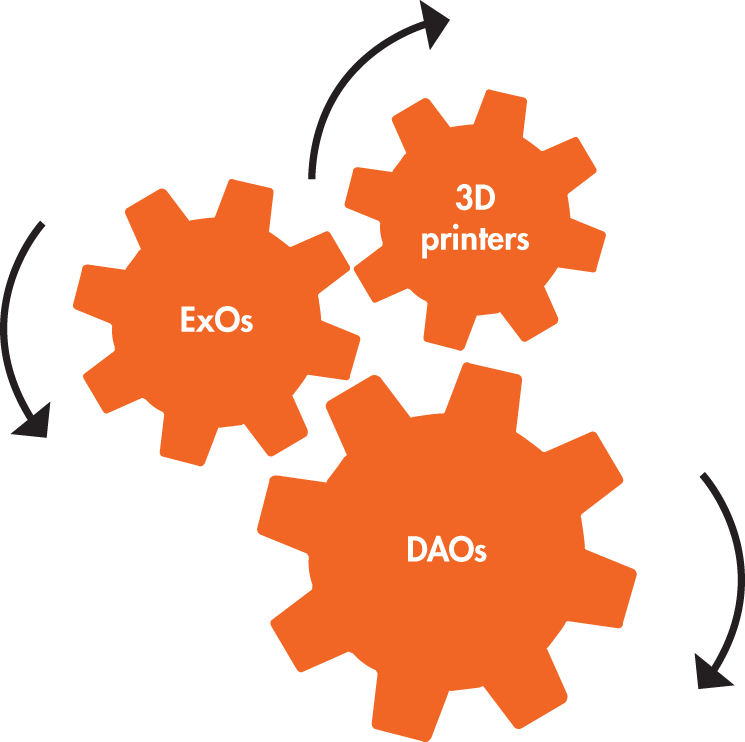

A phenomenon parallel to ExOs is replicators: things that can make copies and variations of themselves. Viruses and all living beings are replicators. But can people create replicators? Yes, absolutely. In addition to familiar shared-economy services, they include AI-based software that can write software by itself, robots that can build robots, and 3D printers that can print copies of themselves. We will also witness more of this in the future. The most important development will probably be the first: software that can write software by itself. Consequently, the combination of DAOs, ExOs, and 3D printers will be explosive.

The technology trio behind replicators