CHAPTER 4: ESTABLISH AN ITSM STEERING COMMITTEE

In our experience, Step Four – the founding of an ITSM Steering Committee, authorized to oversee the design and implementation of the service management model – is the single most critical component of this entire process. Composed (as it should be) of business unit leaders, IT representatives, and subject matter experts, this body will be responsible for dealing with service and process design issues, and for adjudicating and rendering decisions that must be reached, compromises that must be negotiated, and risks that must be mitigated. Used effectively, the members of this board will facilitate and enforce standardized service and process design, testing, and deployment activities. They will also be a key stakeholder in all operational issues that may arise, as well as sponsoring and governing all improvement initiatives.

When assembling this board, there are a number of critical matters that cannot be overlooked or minimized. In fact, we feel so strongly about them that we refer to these tenets as the “Ten Commandments” of organizational IT governance.

1. Ensuring cross-organizational representation: this means including members from all areas of the organization – from Finance to Operations to IT.

2. Writing a charter that clearly spells out the Committee’s responsibility, scope of authority, and primary objectives.

3. Defining (at the initial session, if not prior to that) the Committee’s procedural operations (e.g. who will serve as Chair; how voting will be conducted, and under what circumstances; what constitutes a majority; etc.)

4. Outlining specific procedures for handling exception requests, non-concurrence, and points of order, including veto rights and decision escalation.

5. Widely communicating (to relevant staff and executive leadership) all Committee decisions.

6. Defining and enforcing enterprise service and process standards, including interoperability.

7. Adjudicating disputes between key ITSM functions and roles (e.g. service owners, process owners, stakeholders, suppliers, etc.)

8. Prioritizing, funding and orchestrating enterprise service and process improvement opportunities.

9. Establishing a completion timeframe and set of deliverables for each stage of the ITSM Lifecycle4.

10. Including a “sunset provision” to force periodic evaluation of the Committee’s performance, and to allow removal of the Chair or complete dissolution of the Committee if it fails to achieve its chartered goals.

While, in theory, all “Commandments” should carry equal weight, we feel the last one is the most important for ensuring the long-term success of your transformation effort. People change roles; political winds shift; organizational priorities change. In addition, the very act of implementing new or changed service management practices will transform the organization. Some changes will be large; others small. Yet, each one will alter the organization’s dynamics. The ITSM Steering Committee must stay attuned to this nuance, manage it effectively, and evolve with it, as need be. For all of these reasons, it is strongly recommended that Committee members periodically review and update the Committee’s actions, mandates, scope of authority, and responsibilities.

Not only must the Steering Committee evolve with the organization it serves, it must also be held accountable for its performance. Unaccountable Committees are anathema to service management success; if the Committee fails to achieve its chartered goals within a reasonable period of time (for any reason), deliberate action must be authorized and taken. This may require intervention from a higher authority, for example the CIO or CEO, which is why executive authorization for the Committee must be clearly enumerated in the charter. We do not achieve ITSM success by crowning or coddling ineffectual regimes.

The key to an effective charter is to ensure it contains all the elements necessary for the smooth, efficient operation of the Committee. In our opinion, the charter should include the following sections:

• Background: for clarity’s sake and to provide historical context, it’s desirable to state the conditions that necessitated the Committee’s creation.

• Purpose: this statement clearly and unambiguously declares the reason for the Committee’s existence.

• Scope of authority: this defines the parameters of the Committee’s authority.

• Goal: this establishes the broad goal or goals the Committee is intended to accomplish.

• Objectives: the quantitative or qualitative steps that will lead to achieving the stated goal or goals.

• Membership: this states, by name or title, the Committee’s members. This section may also declare the role each member is expected to assume on the Committee (e.g. Chairperson; Secretary).

• Procedures: this section details how the Committee’s business will be conducted. It typically contains procedures for defining what constitutes a quorum, and includes steps for how to call and conduct official votes, and how decisions shall be rendered.

• Meeting frequency: this defines the frequency of Committee meetings, and may also include a section on how to call ad hoc sessions, if necessary.

• Communication: this specifies how Committee minutes, decisions, action items, etc. are distributed to affected personnel and relevant stakeholders.

• Duration: if time-bound, this dictates the term of the Committee’s existence.

Note: It is strongly recommended that all charters contain a built-in expiration date. This forces the organization to perform an active review of the Committee’s purpose, goals and objectives. Committees with open-ended durations often lose their focus after a year or two of existence, especially if not chaired by a strong, forceful and visionary personality within the organization.

Once the charter has been drafted, and has passed its internal review, it needs to be endorsed – in writing – by the CEO or the CEO’s designee. This legitimatizes the Committee and gives the body more weight and authority. Ideally, you’ll want a permanent Secretary/Facilitator to ensure consistency of action from one session to the next, and serve as the Chairperson’s adjunct. Minutes should be recorded and maintained in a public (i.e. web-based) library that will serve both as a historical reference and ongoing operational resource for new employees, as well as those unfamiliar with the original conditions necessitating any decisions rendered by the Committee.

In the course of executing its mission, the Committee will be required to render decisions and adjudicate disputes. Decisions made in this forum must be communicated as widely as possible. This point cannot be stressed strongly enough. In our opinion, one of the primary reasons that ITSM improvement initiatives fail or become delayed is a lack of communication. Either decisions are not conveyed to those on whom it will have the greatest impact, or the information is incomplete or inaccurate. Change is difficult enough when everyone understands what needs to be done. Don’t unnecessarily complicate matters through poor or non-existent communication practices.

There are a variety of ways in which decisions can be publicized. Experience has shown that a standard format works best. An effective communication mechanism offers several benefits. It:

• Alerts the organization that a decision has been rendered; this is especially true if the decision is entered into a database or content management system that automatically generates messages to specific groups that are established within Active Directory®.

• Presents the decision in an easy-to-understand format (see provided example).

• Provides people with a point of contact for questions or concerns regarding the rendered decision.

• Minimizes confusion and ambiguity.

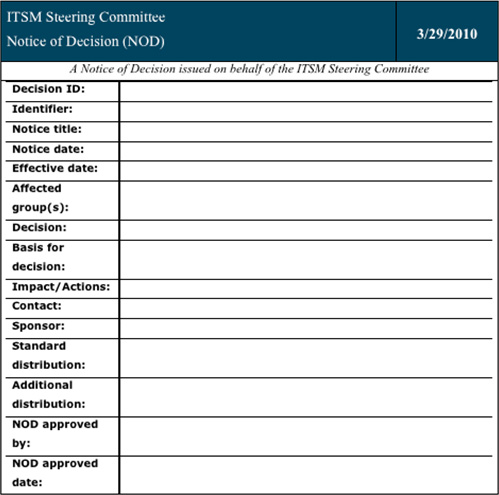

Figure 6 depicts a communication mechanism that has worked particularly well for us.

Figure 6: Notice of Decision (NOD)

As can be seen, the Notice of Decision (NOD) is structured to allow an organization to assign an internal numbering / document identifier scheme for inclusion into a Content or Knowledge Management Database System (KMDBS). This allows staff the ability to search for, and retrieve, information about decisions rendered by the ITSM Steering Committee. When properly used, the NOD acts as an effective communication mechanism to all affected staff and relevant stakeholders.

Note: There will be instances when rendered decisions may have to be modified or reversed. This is normal, and shouldn’t be viewed as “waffling.” Changing circumstances (either internal or external) will necessitate a change in direction. In fact, failing to adapt to surrounding conditions when circumstances dictate that you must is both foolhardy and destructive. Should this situation arise in the course of your project, simply issue a new NOD that clearly explains why the previous decision is no longer applicable, and reference the outdated NOD in the new distribution, so that readers will understand what has changed and why. Not only is this good business practice, but it will develop in the staff the habit of consulting the NOD library.

The effort involved in putting together an ITSM Steering Committee of this nature shouldn’t be minimized or underestimated. More likely than not, the people you’ll most want to have as members of your Committee will decline to serve, either because they will be “too busy” performing their day jobs, or because they will secretly feel unqualified. If they’ve attended the training and education sessions you were foresighted enough to arrange, the prospective members will have a good working knowledge of ITSM, but they won’t (with a few possible exceptions) be experts. They’ll want you – as the ITSM professional – to take charge, chair the Committee, and make most of the major decisions.

As flattering as this may be to you personally and professionally, don’t accept the assignment. You’re an ITSM professional, not a business leader. ITSM exists to enable and support the business; the cart should never be placed in front of the horse. Although it may seem counter-intuitive, it is actually in your own best interest to allow (or force, as the case may be) the business to make the decisions that drive the strategy, design, development and implementation of ITSM best practices. Business representation on the ITSM Steering Committee is a must. It not only ensures that IT capabilities meet business needs, wants, and concerns; it also has the added advantage of continually educating the Committee members on ITSM’s benefits.

This is where the selection of the ITSM Steering Committee Chairperson becomes critically important. The person at the head of the table has to have enough “gravitas” within the organization to lend the proper air of authority to the Committee – especially during its formative period. The Chair needs to be high enough in the organizational hierarchy to compel the attendance and full participation of the other members. Assigned action items won’t be addressed in the stipulated timeframes unless the action item owner knows he or she will be taken to task if the item isn’t addressed. The Chair is ultimately accountable to the CEO. The Committee members must be ultimately accountable to the Chair.

An ITSM Steering Committee with a weak Chairperson is as ineffective as a Committee with no genuine authority or organizational responsibility.

It’s a good idea to attend the first several ITSM Steering Committee meetings. You can coach the members through their duties and responsibilities, as well as answer any tactical questions not clearly addressed by the charter. You can be the Committee’s support, and spiritual leader, but it is up to the Chair and other members to make the Committee an effective body.

What you want to avoid is having a Committee comprised of members who are afraid to make decisions. While agreement is ideal, not every decision will be met with universal approval. It is impossible to please all of the people all of the time. What the Committee must strive for are decisions that have a positive effect on the largest number of people, or a decision that achieves one of the organization’s strategic goals. In your role as observer and mentor, it is your responsibility to alert your business sponsor – or the ITSM Steering Committee Chair, if that’s a more appropriate course of action – if it becomes evident the Committee is ineffective. It may be difficult or uncomfortable to broach the subject, but failing to do so is a risk to your project and to achieving your objectives.

If you are faced with a situation like this, your best course of action is to document the pitfalls of the Committee’s failing to render a decision. Within the corporate world, frame the discussion in terms of potential revenue loss. If you work for a non-profit organization, talk about the failure to serve the targeted constituency, and the negative publicity that will result. Be as objective as you can, but never fail to be honest and straightforward. The organization will be better served for it.

In many organizations, other committees or working groups already exist that will exert influence upon – or be influenced by – the ITSM Steering Committee. Two examples we commonly encounter are Architectural Review Boards and Risk Management Boards. If these exist, ensure these committees and working groups are intimately aware of the progress of your ITSM efforts. Ideally, a representative of the ITSM Steering Committee should be a participating member in those other groups. By engaging with them early in the process, you ensure they have advance notice of potential changes affecting their respective areas. Face-to-face communication is the best form of communication, and this is best accomplished by cross-seeding members of the various groups with a stake in your ITSM initiative into the ITSM Steering Committee, and vice versa.

If other formal committees or working groups don’t exist in your organization, the Steering Committee Chairperson should assign a member to establish and oversee those ancillary boards. A prime example of this is Risk Management.

All new initiatives have inherent risks and opportunities. Responsible leaders (like you) seek to minimize the former and maximize the latter. This means that someone must actively assess the potential risks and opportunities, and craft plans to address them. Identified risks and opportunities should then be assigned to an individual tasked with its care and administration. If no one person is held accountable for crafting an effective mitigation or execution plan, the organization may find itself taking on more risk than it can comfortably handle. Conversely, opportunities will not be fully exploited unless someone actively seeks to take advantage of them.

One final note must be made here. While the broad topic of enterprise governance is well beyond the scope of this book, its importance cannot be overlooked. Suffice it to say that, whatever form and structure your Steering Committee takes, it must align with the organization’s enterprise governance model. For example, the ITSM Steering Committee may need to be established as a subsidiary body beneath the organization’s top-level IT Steering (or IT Strategy) Committee. Unfortunately, enterprise governance is not widely discussed or understood in many organizations; therefore, it is imperative that the CEO, as conduit to the Board, understands and endorses the role the ITSM Steering Committee is tasked to perform.

The opposite may also be true. Many larger organizations, particularly in the financial services area, have established mature enterprise governance models that already incorporate a service management governance body. One example that is growing in prominence is the Service Management Office (SMO), or IT Service Management Office (ITSMO). Alternatively, many organizations have established either a Process Owner Council or Service Owner Council – or both. These may or may not report to a higher-level governance body. If either case is true of your organization, then your challenge is to either structure the ITSM Steering Committee to align with these existing entities (while avoiding overlapping authority), or, more likely, to modify and/or reconstitute these authorities to ensure that the Steering Committee goals discussed in this chapter are achieved.

As previously stated (and as will be stated again), implementing a Service Management model will change the organization’s dynamics. It is important to recognize, and plan for, the inevitable changes in both organizational structure and employee job responsibilities, as well as changed interaction between departments.

The ITSM Steering Committee is the organizational “brain” of your Service Management implementation. Therefore, its care and feeding should be paramount among your priorities. Neglect it at your own peril.

In summary, the actions you want to take in this step are:

1. Assemble an ITSM Steering Committee with cross-organizational representation.

2. Draft a charter outlining the Committee’s role, responsibilities, and scope of authority.

3. Educate the Committee members on their duties and areas of responsibility.

4. Formalize a standardized, repeatable communication strategy, and use it consistently.

5. Create a repository for housing and maintaining a historical record of Committee decisions and issues.

6. Ensure the ITSM Steering Committee is properly aligned with the organization’s enterprise governance model, including other groups with which it must interact.

Congratulations! You are now ready to leave the Service Strategy phase of the Lifecycle and enter Service Design.

4 This topic is covered in more detail in Step Eight: Define a Standard Process Development Approach (Chapter 8).