Systems thinking simplified – four primary concepts

In the last chapter, we tried to provide an overview of how the science of General Systems Theory has evolved from the early 1920s to now. Our own personal experiences demonstrated that the theory is not always easy to understand.

We have been actively studying the principles of Systems Thinking since the late 1980s. Following our review of the literature we felt that it was important to be able to translate these principles into a format that was relatively easy for the typical manager to be able to understand and embed within their management practices. To do this we attempted to distil the primary concepts into a few simple concepts and models that enable our clients to quickly understand the benefits of this new way of thinking. We have developed a set of four basic concepts that represent the fundamental principles of General Systems Theory. However, we are certainly not implying that this is all you need to understand this field of study, but with a good understanding of these four concepts, you can begin to apply the primary concepts – and as a result, you can begin looking at the world as a systems thinker.

These four primary concepts are:

![]() Concept 1 – The Seven Levels of Living Systems

Concept 1 – The Seven Levels of Living Systems

![]() Concept 2 – The 12 Natural Laws of Living Systems

Concept 2 – The 12 Natural Laws of Living Systems

Let us examine each in turn so that we can see how they can be applied within any organisation as you work to improve your practices of planning, people, leadership and change. In the next chapter, we will dig deeper and show how these concepts are directly related to managing the human resource function within your organisation, to maximise your ‘people power’.

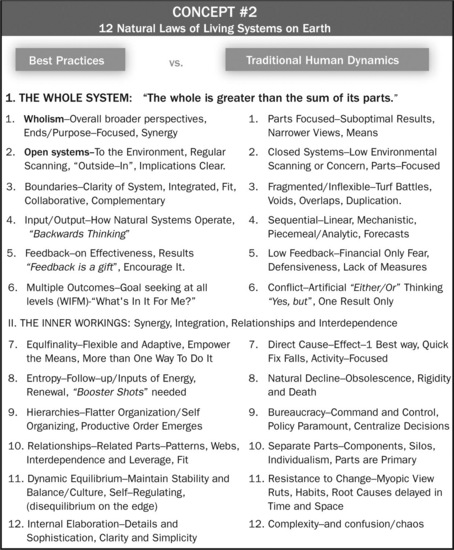

Concept 1 – The Seven Levels of Living Systems

This first concept describes one component of the scientific classification process referenced in the quotation from Geoffrey Vickers in Chapter 4. This concept is presented as a visual model in Figure 5.1.

The first part of this concept is the seven levels that represent the hierarchy of life, which include:

When enough specific cells of a specific nature exist together, an organ is created, such as a heart, a lung or a brain.

When a specific set of organs are united in a pre-designed manner, an individual creature is formed – a person, a fish, a bird.

When a series of work groups or work teams join together, they create an organisation that has a specific purpose to fulfil.

Obviously, from the perspective of any organisation, you need to focus only on four of these seven levels. Work at the cellular and organ level is left to the scientific and medical community when help is needed. Work at the level of the whole earth is beyond any one group’s influence or responsibility. However, because of the inter-connectedness of our world as a system, each person, each group and each community does have responsibility for what we do or don’t do in our lives that influences our world – either in a positive or a negative way.

At an organisational level, we pay attention to the individuals who make up the teams and groups of our organisations and our organisation’s influence or impact on the community or society within which we operate. These are levels 3–6 in the hierarchy.

The second element of this concept is illustrated as the ‘Six Rings of Reality’. The series of concentric circles begins with Level 3 – Self and expands to include Level 4 – Workteams, Level 5 – the Total Organisation and Level 6 – Community/Society. In addition, the sub-levels of 3-A – One-to-One relationships, Level 4-A – Inter-Departmental relationships and Level 5-A Inter-Organisational relationships with their environment in the community are included.

This model reflects the three levels at which potentials for conflict, or collaboration, occurs: 3-A, 4-A and 5-A. These could become the ‘collision points’ between the various components of your world.

The ‘Readiness Arrow’ emanating from the centre of the Rings of Focus conveys the sequence in which an individual, a group, an organisation or a society is ‘ready for change’. If I’m not ready to embrace a particular change initiative, my conversations with another individual, one-on-one (Level 3-A), will reflect my level of readiness. In fact, I’ll probably be trying to convince the other person to agree with my particular point of view.

This same sequence occurs at Level 4-A between work groups, work teams or departments of our organisation. This is sometimes reflected by the struggles that occur during the annual budget allocation process or discussions about the distribution of other resources such as staffing, training and development opportunities, or equipment allocation. Conflict can also occur here when the actions of one department create problems for another. An example of this within a manufacturing company, for example, can occur when staff from the marketing or sales department generate a level of sales commitments that the production department cannot possibly fulfil. The communication breakdown between the various groups creates a huge problem because the demand and the supply do not match. This can create a series of other systemic problems that roll out like a ripple effect – credibility with customers is negatively impacted, customer satisfaction ratings are negatively impacted, sales bonuses may be compromised, unplanned overtime work may be required and relationships between the various departments are damaged.

Within a library setting, decisions made in one department, such as changes in staffing schedules, could have an unintended impact on the workload of another department, which will create negative repercussions between the staff of the two departments. Requests for additional staffing resources during a period of constraint or limited resource availability can generate conflict between different departments.

At Level 5-A, actions taken by the organisation as a whole may create difficulties or pressures for customers, external stakeholders or the community at large. This could include actions such as eliminating specific product lines or services, expanding services into an entirely new area or location, which negatively impacts other local suppliers, or aggressive labour action over unsettled labour or contract issues that lead to a strike or walkout by unionised staff, or a lockout by management. In any one of these cases, the organisational activity has a direct and undesirable impact on the community that the organisation is supposed to serve.

When one looks at this model, it is easy to see how organisational change can be impacted – at any one of several different levels. In reality, the notion of ‘organisational change’ is really an inappropriate description of what actually happens. As the origin of any successful change is the individual’s personal frame of mind and response once the change has been announced, real change occurs only when enough individuals begin to move in the direction of the desired change. When that happens we tend to call it organisational change, but really it is collective individual change that creates teams that change, which leads to changes for the organisation.

This model of the various levels of living systems also has one additional feature that needs to be clarified. When developing a planning initiative or when planning for a change initiative, it is very important to be able to clearly identify the target level of the initiative. Once the specific level is confirmed – such as the Work Team Level, Organisation Level or Community Level – we must understand that the initiative will impact every level below, so each of these other levels must also be factored into the plans for change. Sometimes we can over-complicate a situation by inferring that it affects levels above the targeted level for change. For example, if the change is directed at a specific work team, it must include each of the individuals within the team and also factor in the interpersonal relationships between the individuals within the team. Once the change has been completed, it may have an impact on other teams within the department, but this is a matter of influence impact as opposed to direct impact. The impact on the other teams within the department is outside of the direct control of the team leader.

This point was made evident to me many years ago, when I was a member of a small team of six staff members in an Area Office of a provincial government department in Ontario. Our Area Manager introduced a new methodology for us to develop our annual operational plans, as an Area Team. It directly impacted the development of annual work plans for all six members of our team, without exception. He did not have the authority to ask other Area Teams within our Region to adopt this same approach. However, over time, as other Area Managers began to see the overall improvement in the performance of our team, which had to cope with the same resource restrictions and client expectations as their teams, they began to ask questions. Our Manager’s explanation about our new approach to ‘planning our work and working our plan’ was rejected by the other Area Managers as ‘not workable’ in their areas. So, our focus stayed on our own team only for nearly two years. Then, as they gradually began to see the real benefits of this new initiative, each Area Manager began to replicate the process in their own area. As the work results of the three Area Office Teams within our Region of the province began to draw attention from other Regional Managers, a groundswell of change began to unfold. It took almost six years to reach its ultimate level where all Area Teams within all six Regional Offices of the Provincial Department were using the new planning approach.

What’s important to remember from this example is that the original initiative was directed at the team level and it required all members of the team to participate to achieve success. The influence impact ‘up the system’ was unplanned and became an added bonus. If, on the other hand, this same initiative had been introduced at the Provincial Department level, which was the total organisation, it would have required all six Regional Offices, all 22 Area Offices and every staff member within those offices – about 150 individuals – to become actively involved in supporting the change. Driving change from the top of the organisation can be achieved, but it will face some resistance to conform. Changes driven from the lower levels of the organisation can be effective throughout the organisation, but they will take longer because there is no positional authority to mandate the change.

We will dig deeper into the nature of change and the responses to change later in this chapter, when we discuss Concept 4 – The Emotional Rollercoaster of Change.

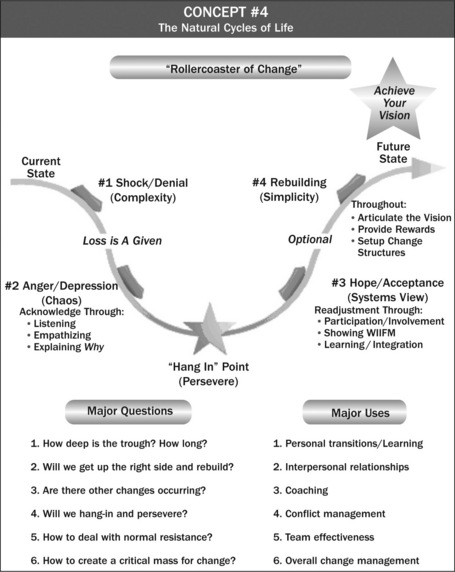

Concept 2 – The 12 Natural Laws of Living Systems

After years of distilling the detailed information on the theoretical side of General Systems Theory, we have been able to formulate a set of what we call the ‘12 Natural Laws of Living Systems on Earth’. These 12 laws are further broken down into two groups – a set of six laws that influence ‘The Whole System’ and a set of six laws that influence what happens within ‘The Inner Workings’ of a system.

In presenting this concept (Figure 5.2), we have identified the laws that emanate from the study of systems thinking theory on the left-hand side of the chart and we call these the ‘Best Practices’, as compared with the contrasting laws that are included on the right-hand side, which we describe as the ‘Traditional Human Dynamics’ that are evident in many organisations where analytical thinking and problem solving are the primary methods being used.

Under Part I, ‘The Whole System’ includes the following six Natural Laws (1–6 below):

1 Holism

This provides the full, broad perspective of what is happening within the organisation, as opposed to an approach that begins by looking at the individual parts. We often describe this perspective as ‘getting the helicopter view – at the 5000-foot level’, rather than the close-up view one gets when examining the organisational enterprise department by department.

2 Open Systems

Systems that only focus internally and fail to consider the external impact of environmental factors are susceptible either to being blind-sided by events outside of the organisation that should have been avoided, or of missing ideal opportunities occurring outside of the organisation that should have been captured and turned into an advantage. Environmental factors are factors that are outside of your control – but if you don’t monitor them and attend to them properly, then you could be severely disadvantaged. When a system fails to factor in environmental influences, it becomes a closed system – which becomes a vacuum. Nature abhors a vacuum. To be effective, a system must be open to the environment and learn how to read the environment and use that information to improve decision-making. A sailor cannot control the wind, which is an environmental factor. However, the captain needs to be able to scan the environment and read the wind. The trick then is to use the information gathered to decide what moves are required to follow the best course, based upon the wind conditions, that will enable him or her to achieve the desired destination.

3 Boundaries

Every living system has boundaries. Even an amoeba has a boundary, even though it can move and flow fluidly in many different directions and configurations. However, its boundaries are not borders. They are permeable, allowing nutrients to enter and waste to be excreted. The various boundaries of an organisational enterprise were outlined in Concept 1 – the Levels of Living Systems. These boundaries help to identify the sub-groups within an organisation and clarify the specific function that they fulfil. However, if these boundaries become impermeable borders, they become counter-productive.

4 Input/output

Any system has inputs and outputs. In the process of baking, you have the various ingredients (inputs) and when you mix them in the proper quantities and sequence, you end up with a cake (output). The same applies in a manufacturing company like a car plant or a clothing firm. It also applies to the writing of this book – the ideas and the words of the author are the inputs and the finished book is the output. The distinction between a ‘systems thinking approach’ and that of the ‘analytical thinking approach’ is the sequence in which these are covered. In a systems thinking approach, we start with a clear description of the output or outcome that is desired – in the Future State. That becomes the goal or target to be achieved. Then, using the concept of backwards thinking, we return – to the Present State – and determine what type and quantity of inputs are needed to close the gap between the present state and the desired future state. The sequence in these two approaches is critical – ‘Begin with the end in mind’, which Stephen Covey labels as Habit 2 in his bestselling book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.1 For any successful journey, you need two vital pieces of information – your destination and your starting point. It’s always wiser to be clear about your destination before you start out. Otherwise, you’ll feel like Alice in Wonderland, in Lewis Carroll’s famous children’s story when she asks for directions from the Cheshire Cat. He asked Alice, ‘Where are you going?’ When she answered, ‘I don’t know, I’m not really sure’, he responded, ‘Well then it doesn’t much matter; any road will do.’ It’s important to be sure about the destination, the end result or the desired outcomes before you start.

5 Feedback

To ensure that any operating system is performing as desired, you need to be able to seek and receive regular feedback that tells you whether or not you are still on track. If you are, then keep up the good work. If you’re not, then it is time to slow down or stop until you can figure out what changes are needed to enable you to get back on track. Many organisations seek a limited amount of feedback, which is usually related only to their financial status. To be fully effective, you need feedback from multiple sources and on multiple subjects, such as employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, financial viability, and process and system effectiveness. This provides a comprehensive score card for tracking success. Feedback can provide clues about changes that might be needed to the volume and quality of your inputs, or to the processes you are using to develop your products and deliver your services, so that you achieve the results you are expecting.

6 Multiple Outcomes

Very seldom do we want or expect a single outcome from a particular action or process. For example, if we develop and provide a client with a particular product or service, we are interested in several things, such as: Did the product or service provide what they needed? Did it really work for them? Was the service courteous and timely? Will they do business with us again? Would they refer us to an acquaintance or colleague who was looking for the products or services that we provide? Each of these is a slightly different outcome. Each has its own value and, as a group, they are all critical to enable us to fine-tune and adjust our efforts from time to time. Too often, we are fixated on one single outcome and end up missing other equally important outcomes.

These first six Natural Laws are the ingredients for designing a working model of an effectively operating system. This will be outlined when we explore Concept 3.

Under Part II, the ‘Inner Workings’ of any operating system must consider and handle the impacts generated from the next six Natural Laws (7–12 below):

7 Equifinality

This law states that there is more than one way to achieve a specific outcome or result. Although some options may yield better results than others, there are always circumstances at play that may make it smarter to go with the second or third best option, because it best addresses the external environmental factors that we cannot control. For example, I live in a small community south of the City of Vancouver in British Columbia. Whenever I need to drive to Vancouver Airport to catch a plane to work with clients across Canada, I have to contend with various levels of traffic volume that can become restricted at the point where I need to cross the Fraser River. I can take one road that uses a tunnel to cross under the river, or I can take a different road that uses a bridge to cross over the river. Each route is almost exactly the same distance from my home to the airport – each one covers two sides of a rectangle on the map. Both can get me to the same location without any excess travel. Although I have my preferred route, I must always be open to checking the traffic patterns and listening for traffic update reports. If there is heavy congestion or a traffic jam on one of the two routes, then I must remain flexible and choose the alternative route. This is a decision that I must make at a particular point in the journey. If I miss this decision point, then I’m stuck with the route I’m on, even if it’s the slower one on that day. Colleagues of mine, who are faced with the same choice, use the alternative route to mine. And in the end, it often doesn’t make one bit of difference – because there is more than one way to achieve what we want to achieve. When deciding for yourself, the choice is up to you. When you are part of a team or work group, you need to seek input from others and then make your choice as a group, so that there is group support for the selected decision.

8 Entropy

The law of entropy explains that when someone is born, they begin to die. When a new product or project is launched, it begins to die. If a system is left to operate without periodic ‘booster shots’ that help to adapt it, motivate it or re-energise it, it will run down and eventually fail. This means that we need to use feedback to determine when these adjustments need to be introduced to maintain maximum results from the system. This affects each one of us as individuals and as team members too. Remember the spirit of excitement when you are on a team that is given a new project assignment. As the weeks unfold and you are faced with the tedious work related to completing the assignment, while also juggling your other duties, spirit starts to drain away. That’s when a new injection of ideas, or new blood or a midpoint celebration is needed, to refuel the group and provide the push that is needed to reach the final target.

9 Hierarchies

In nature, hierarchies are common. We can see this when we examine the various levels of the food chain within the animal kingdom. In organisations, hierarchies are natural too and can be very helpful in providing the various levels of leadership, task assignment and authority for decision-making or resource allocation. By contrast, bureaucracies are not normal in nature. They shouldn’t be in organisations either, because this tends to slow the activity down needlessly. With agreement on the desired outcomes, and a sense of trust and accountability at each level within the hierarchy, bureaucracy becomes unnecessary. Without these features in place, bureaucracy will always prevail as a substitute for unclear focus, a lack of trust and a lack of accountability.

10 Relationship of Related Parts

With a hierarchy in operation and specific duties assigned to specific individuals or groups, it is important to monitor the ongoing relationships that exist between the various parts. This was evident when we looked at the potential collision points between levels in the Seven Levels of Living Systems. It is common practice to design and structure an organisation around functional areas of responsibility. This creates specific departments or sections, which provide specialised services on behalf of the whole organisation. This approach can be beneficial because it brings those individuals with the same critical skills together – such as marketing, finance or human resources – so that their expertise can be leveraged in the most effective way for the organisation’s overall success. However, there is a negative side to this approach. These specialised departments and sections can easily become ‘silos’ that are insulated and isolated from other departments and sections. Communication between the groups is diminished. The synergy of the whole is severely constrained and compromised. Opportunities for innovative thinking and creativity are stifled. The organisation soon becomes a ‘collection of parts’ and ceases to operate as a holistic unit. It is critical that strong, positive relationships are fostered and maintained between the groups that make up the whole organisation. Through a healthy level of interdependency, better results are achieved. When all managers in every department are consciously thinking about and attending to the issues of marketing opportunities, financial practices and human resource management skills with their own staff teams, these functional areas are quickly raised to a much more effective level of execution, than if they are left totally to the ‘specialists’.

11 Dynamic Equilibrium

When a system operates in a state of ‘dynamic equilibrium’, there is a level of tension between opposing forces that is healthy, intentional and designed to achieve maximum results. As an example of this in real life, think about a saucepan of water that you are heating to boil some potatoes. Once the water has reached boiling point, you add the potatoes and the temperature drops a bit. As the heat continues to build, the water starts to boil again, and before you know it, it starts to boil and spill over the edge of the pan. You have to quickly readjust the heat, to bring it down a bit, until you can find that point where the water continues to boil – but not over-boil. You can also adjust the lid on the pot, to allow some of the internal pressure in this ‘closed system’ to escape, thus helping to establish the correct set of circumstances to achieve your goal. That is the point of dynamic equilibrium, the point where you are cooking the potatoes at the maximum level of effectiveness. It is a balancing act between not enough heat and too much heat, to achieve the continuous, rolling boil that is needed to cook the potatoes quickly and maintain the texture that you want.

Organisational systems also exhibit this situation of working to find the ‘right balance’ between opposing forces. How do we schedule staff to ensure that we have enough on duty at various points during a normal working day or week to handle the anticipated volume of business, without being over-staffed? We don’t want extra staff on duty, if there isn’t enough to keep them fully occupied, because that drives up staff overheads. It also means that we may not have enough staff or enough available staff time for use at other periods during the week, resulting in people having to work extra hours at overtime rates. This type of dynamic tension or dynamic equilibrium can exist between management and trades unions, as each works to achieve the most optimal working conditions within the workplace. It can occur between managers and staff with regards to approving expenditures and managing the budget in the most effective way possible. For it to function effectively, our people need to be receptive to change, to maintain a degree of flexibility, where some ‘give and take’ is required. When an organisation is able to create this healthy degree of dynamic equilibrium, they can operate at peak performance, where they are functioning ‘on the edge’ and maximising their effectiveness. And it is important to recognise that most individuals cannot operate ‘on the edge’ indefinitely. They also need a break, to relieve the tension for a while, so that they can recover and re-energise themselves, and be ready to return to action.

12 Internal Elaboration

For any system to work effectively it must have the degree of complexity and detail that is needed to do what it is designed to do – without going too far. The system and its operating procedures must be sufficiently sophisticated that your outcomes can be achieved. However, it is so easy to slip past that point of optimal sophistication and become over-complicated. The trick is to make the operating system ‘elegantly simple’ – elegant enough to be successful and simple enough to be efficient and easy to operate. Policies and procedures, operating manuals, service standards and other performance guidelines are all designed to achieve this result. Sometimes we let them become too sophisticated and they end up being complicated. Too many policies or rules can create a top-heavy bureaucracy that stifles individual accountability and initiative. The most glaring example of this for me was a colleague who had taken a new job with a major bank. His first week of orientation included an assignment where he was brought into a boardroom with 12 volumes of policies and procedures lined up in the centre of the table. He was told to read these 12 books so that he would be clear about the ‘rules of the banking business’, which was the way they operated. He did spend time going through these reference volumes – but my questions are: ‘Did he remember very many of the policies and procedures a month later?’ ‘Did this approach to orientation really help him to be better prepared to come to work the following week with excitement and enthusiasm?’ ‘Did the organisation really need to have 12 volumes of policies and procedures to ensure staff acted responsibly?’ ‘What kind of “first impression” did this approach to staff orientation create with a newly hired employee?’ Effective organisations make it easy for staff to understand what they are expected to do to contribute to organisational success – and they do so in a very clear, unambiguous way – so that staff are impressed and remember it, day after day.

These last six natural laws outline what needs to happen within an organisation, within an operating system. Each is focused on the relationships between the parts, the relationships between the people, the relationships between the ‘rules of the game’ and ‘the players of the game’.

The first six natural laws are directed at the whole organisation and its practices for planning and for introducing change. The last six outline the internal relationship issues that need to be monitored and addressed, to ensure change occurs in a successful way.

Concept 3 – The A-B-C-D-E Systems Thinking Approach

As noted in the previous section on the 12 Natural Laws of Living Systems, the first six laws are fundamental to an organisation’s process for developing future focused plans and successfully implementing the changes that are imbedded within the plan.

Concept 3 presents a working model for how organisations, teams and individuals can develop plans for their own future growth and development. It embraces the fundamental principles of systems thinking – and it is designed to be a very simple, easy-to-remember visual model that people can readily recall, as they are trying to bring about change. We have used the English language alphabetical letters to help make this approach more memorable. It’s easy to think about the ‘A-B-C-D-E’s of good planning’.

This model has five components, as shown in Figure 5.3, and there is a very simple question related to each one. The sequence of the process is very important. Remember that it is important to ‘begin with the end in mind’. That should mean starting with Phase A – right? No, not really. One of the best practices of good planning is to start with an external environmental scan that is future-focused, even before you identify your desired outcomes.

[E] Future Environmental Scan: ‘What’s ongoing that may change in the future?’

In developing a sound plan, even before you identify the outputs or outcomes, as part of your ideal future state you need to conduct a future-focused environmental scan. This is different than a current-state environmental scan. A current-state environmental scan is equivalent to looking out the window to see what the weather is like. A future-focused environmental scan would include tuning in to the latest weather report on the radio or TV, to better understand the weather forecasted, so that you know whether to proceed with your outdoor plans or not. If a storm is on the horizon, you may need to re-schedule such activities. If you don’t look further out into the future, you could end up starting an activity only to have the storm arrive part way through, ruining the event, which you’ll probably end up rescheduling. There are many different techniques that can be used to complete this step. We have found that when the planning team and leadership team conduct this exercise together, they not only obtain a variety of opinions from several sources that might not generally be considered, but they also realise that the members of their organisation are well tuned in to what is going on around them and what it is that is heading their way. The technique that we generally use is one that examines seven different variables that are captured within the acronym SKEPTIC. We will identify these specific variables later, when we explore the method used to develop a strategic human resource management plan, using the systems thinking framework.

[A] Outputs: ‘Where do we want to be?’

This is the second stage and it is the point where you describe what you are trying to create, produce or achieve. This becomes your ‘ideal future state’. The process of bringing a team together to develop a statement of your vision of the future, your specific mission as an organisation and your core values can be a very exciting and liberating exercise. It produces a strong, powerful and motivating image for people to focus on, as they go about their day-to-day work.

In 1961, US President John F. Kennedy made a bold declaration when he stated that the US Space Programme would put a man on the moon and bring him back safely before the end of the decade. I’m sure that there must have been a huge amount of consternation, disbelief, confusion and possibly even some anger around the coffee pots and in the halls of NASA – the National Aeronautics and Space Administration – the next morning, following this announcement to the world on public television. Comments such as:

‘Does he have any idea about what he is saying?’

‘We don’t have the staff or the budget needed to make it happen.’

were probably heard frequently over the next few weeks and months.

Yet, despite all of this negativity, the world held its collective breath on 21 July 1969 when astronaut Neil Armstrong stepped off the last step of the lunar module landing craft ‘The Eagle’ and planted his feet firmly on the surface of the Moon at The Sea of Tranquility. His famous quote said it all:

‘That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.’2

He was joined by one of his colleagues Edwin ‘Buzz’ Armstrong twenty minutes later, while their partner Michael Collins continued to orbit in the mother ship Columbia, which was the vehicle that was needed to get all of them safely back to earth – to fully complete the vision outlined by President Kennedy nine years earlier.

Powerful visions of possibility can galvanise and mobilise a dedicated team of individuals to make the impossible a reality. This has been demonstrated over and over again by teams and organisations all around the globe. Although the scale of their dreams may have been quite different from that declared by President Kennedy, they were nonetheless every bit as important for the success of their individual organisations.

[B] Feedback Loop: ‘How will we know when we get there?’

Having a powerful vision of what your ideal future looks like, which is your description of success, is very important. However, you also need specific targets to aim for, along with intermediate targets that can provide feedback telling you whether you are still ‘on track’ so that you can assess the probability of achieving your ideal future state. These intermediate targets serve as signposts along your journey to provide information that says you have chosen the right route and to provide information about how close you are to the ultimate target. They are like the road signs or route markers that we rely on when travelling in an unfamiliar area, which are designed to prevent us from getting lost, or to help us get back on the right track when we are lost.

Good feedback provides tangible information that is quantifiable and able to be monitored and tracked, to assess progress. It could include time or date targets, financial targets, milestone points within a large project, and reactions from customers or from staff. If we go back to the Moon-landing example, there was a specific goal – putting a man on the Moon, there were specific dates – by 31 December 1969, and specific conditions – there and back safely.

For maximum benefit, feedback needs to be provided in a steady and regular way, so that we don’t become lulled into a false sense of security only to be shocked at the last moment when it becomes clear we won’t make the targets. Organisations do this routinely with financial information related to budget expenditures. There are monthly financial statements, a series of quarterly financial statements including variance reports and a year-end budget summary report. That’s up to 17 reports over a 12-month period. A similar approach to frequency reports in other areas, such as feedback on levels of customer satisfaction, staff satisfaction and periodic progress reports on major initiatives, is needed.

The best way to determine what needs to be tracked and reported on regularly is to take the very words used to describe your ideal future state, identify which components of those statements are needed for ongoing monitoring and then develop specific, quantifiable techniques for tracking them. Remember too that it is the inter-relationship between all of these ‘key measures of success’ that is important. Being successful in one area, such as financial targets, at the expense of another legitimate target, such as customer satisfaction, is not healthy. The targets must be able to be fully integrated, with each one contributing to the overall description of success. I’m reminded of this from time to time when I’m driving in the car with my wife on a trip. She has been known to say: ‘We’re lost aren’t we?’ If I respond: ‘That could be – but at least we’re making good time!’, I’m in trouble – in fact more trouble than I care to think about. Sometimes, we need to read the signals, stop and get directions, in order to get back on track to achieve our goals.

[C] Inputs: ‘Where are we now?’

This is the fourth phase of this approach to planning. For many organisations and individuals, this is where they were taught to start the planning process. You can see this if you open a planning document and the first section outlines in detail the ‘current-state situation’ that the organisation is facing. When you use the current-state assessment as the starting point for your planning exercises, it is easy to be overwhelmed by the complexity and the magnitude of the real-life issues and situations that you need to overcome. The current-state assessment can blind us to the true possibilities that exist. This produces a very limiting influence on the staff developing the plan, as well as those needed to carry out the plan. The hypothetical comments attributed to the NASA staff the morning after President Kennedy’s announcement are an example of this frame of mind.

This does not mean that we should not be realistic. Indeed, we do need to be very realistic – and this is exactly the time to do it, now, after we have examined the future environmental factors, clarified our vision of the desired future and laid out the measures of success towards the attainment of that future. To use a travel metaphor, our destination has been set, we’ve checked the weather conditions and confirmed when we want to be at our destination and now it’s time to determine what we need to pack up and take along, confirm our travel arrangements (tickets, full tank of petrol, bike in working order or good pair of walking boots, depending on our chosen mode of travel) and begin to prepare to start our journey.

In this phase we need to do some stocktaking, to determine the available resources we have to work with, such as financial resources, human resources, available skills, available technology or equipment, and the time required to achieve our goals. This is also the time to candidly identify the issues and concerns we are currently facing that will either produce a need for us to accelerate our plans or prevent us from allocating the necessary amount of resources to the plan being formulated. This analysis provides us with all of the information we need to ‘put in’ to the plan for change – the Inputs. Knowing what our Outputs are expected to be, how we are going to track progress through our Feedback and being conscious of the Environmental Factors that could influence our efforts, we are now ready to proceed to the final phase – the Throughputs, to use the language of systems thinking.

There is one very interesting feature that occurs when you are using a systems thinking approach to developing a plan. When you are working on the Environmental Scanning, the Outputs and the Feedback Loop, which are the ‘strategic components of a plan’, those individuals who are ‘big picture thinkers’ will be in their element, because this is the stuff that excites them. Their contribution is critical during these phases of formulating a plan. In the meantime, those individuals who are pragmatists and realists, who thrive on the specific details of bringing a plan to fruition, will be frustrated and disconnected, because these discussions may be too abstract for them to be able to focus on. Then, once you reach Phases C and D and begin to look at the ‘real issues’, the pragmatists come alive and become intimately involved, because this is the real stuff that they can work with to produce tangible results. At this point, the idealists and visionary members of the group start to disengage, because the detail work is too boring and mundane for them to pay attention to. The real trick is to make sure that you have a good combination of each type on your Planning Team – and that they fully understand this dynamic and are aware of how various individual types will be able to contribute, in different ways, at the appropriate time.

A team full of visionary types only will have a marvellous discussion about creating a new world – but they’ll never get down to doing anything about it. By contrast, a team full of pragmatists will ensure that every detail of the plan is fully carried out – but their plan will probably resemble something that is very close to the status quo and won’t enable the organisation to advance very far. Magic occurs when both groups work together in a synchronised, harmonious way. That’s how really positive change occurs.

There is a famous quote from Margaret Mead, the noted American anthropologist and author (1901–1978) who studied human interactions in many developing countries, that is appropriate to the discussion about bringing a group of people together to achieve something:

[D] Throughputs: ‘How do we get there?’

This is the final phase of the planning and change process. This is where change occurs – or not – depending on the degree of success that is achieved. Just because this is the final phase doesn’t meant that it is the end. In fact it is both – the beginning of the end and the end of the beginning. As we work through this phase, we end up recycling right into the next planning phase, because in best practice organisations this process is a continual one that continues year after year. They develop a continuous planning and change management process. We call this approach Strategic Management. This phrase intentionally includes the ‘strategic’ portion of strategic planning and the ‘management’ portion of change management. For lasting success, both components are needed – good strategic planning practices and good change management practices.

We have seen far too many examples of organisations that are guilty of either of these two glaring management errors:

![]() Developing plans and then failing to execute and bring about the changes as outlined. This is the dreaded ‘SPOTS Syndrome’ – Strategic Plan On Top Shelf, gathering dust. When this occurs, staff become frustrated, cynical and disenchanted, because the potential benefits are never realised.

Developing plans and then failing to execute and bring about the changes as outlined. This is the dreaded ‘SPOTS Syndrome’ – Strategic Plan On Top Shelf, gathering dust. When this occurs, staff become frustrated, cynical and disenchanted, because the potential benefits are never realised.

![]() Attempting to introduce major changes without having a clearly articulated plan in place that provides a sound rationale for the change. When this occurs, staff are confused and feel like victims, because there is little or no explanation as to why the change is required and what things will look like after the changes are in place.

Attempting to introduce major changes without having a clearly articulated plan in place that provides a sound rationale for the change. When this occurs, staff are confused and feel like victims, because there is little or no explanation as to why the change is required and what things will look like after the changes are in place.

In this phase you begin the process of creating intentional change. What’s the point of putting a detailed plan together, if all you are planning to do is maintain the status quo? If that’s the case, don’t waste time developing a plan – just keep doing what you’ve been doing and hope for the best. Here we take all of the various inputs that you have to work with and we ‘put them through a process of change’ (throughputs) in order to achieve the desired outputs. Inputs → Throughputs → Outputs. This is the normal process used to create anything – a car, a cake, a book, a new program, a successful organisation. In systems thinking, the primary difference is that we start with the outputs first, and then apply the skills of backwards thinking to return to the inputs, before we start the throughput phase as outlined earlier.

Because this is planned change, you can increase your odds of success when you become very skilled at anticipating the types of emotional response that you are most likely to encounter as the plan unfolds and the changes begin to occur. Human behaviour during periods of change is actually very normal, very natural and very predictable. Armed with this awareness, you will be better prepared to face, appropriately address and resolve the issues that people experience as they adapt to the personal adjustments each is required to make in order to embrace the changes that will help to achieve the ideal future state. The next section on Concept 4 will delve into the dynamics of change in detail.

In summary, we have discovered in working with clients that following the simple A-B-C-D-E planning process and asking the related questions at each phase provides the template for sound planning and change. As we noted in the section on the Brief History of the Science of Systems Thinking, Stephen Haines and I began our venture into this field by looking for a better way to conduct strategic planning. We backed into the field of systems thinking. I wish that we could have been smart enough to grasp the concepts of systems thinking up front and then used them to develop a better strategic planning model. If we had, some of the situations we encountered would have made more sense to us when they occurred and we would have been better prepared to deal with them. We had to go through the process of exploration and trial and error before we landed on the solution that made the most sense. That is not uncommon. Remember, as noted in the Chapter 1, ‘An education at the school of hard knocks can be very valuable, but the tuition can be very expensive’.

Later, as we examine an approach for developing a Strategic Human Resource Management Plan – or a People Plan – as we call it, you’ll see that the more detailed planning model we have developed is merely an expanded version of this simple Systems Thinking Framework. It covers the same five phases, in the same order, and digs deeper at each phase because of the level of complexity of the planning task at hand.

By keeping the simple A-B-C-D-E model framed in my mind, I am able to have different conversations with people that produce better results. This is true, whether:

![]() I’m having a discussion with a clerk in a shop where I am not receiving the service I need, or when

I’m having a discussion with a clerk in a shop where I am not receiving the service I need, or when

![]() I’m getting the runaround and numerous transfers on a complicated phone enquiry, or when

I’m getting the runaround and numerous transfers on a complicated phone enquiry, or when

![]() I’m having a confrontational conversation with a client, colleague or co-worker, or when

I’m having a confrontational conversation with a client, colleague or co-worker, or when

![]() I’m having a discussion with a family member about something where we have different points of view, or when

I’m having a discussion with a family member about something where we have different points of view, or when

![]() I’m in a situation where I need to go through a process that is critical and possibly uncomfortable, such as being wise enough to handle the frustration of clearing security at an airport, without becoming impatient or upset.

I’m in a situation where I need to go through a process that is critical and possibly uncomfortable, such as being wise enough to handle the frustration of clearing security at an airport, without becoming impatient or upset.

I always try to remind myself of my ‘desired outcomes’, which in the last example are to get through the security check with as little difficulty as possible, and to board my plane on time. When I forget this, I usually end up being detained for a more thorough check, becoming very frustrated and possibly angry and risk missing my flight entirely.

By keeping the ‘end in mind’, it is easier to deal with immediate difficulties. To reinforce the importance of this point, we jokingly recommend that clients have this simple model tattooed on the inside of their eyelids, so that they will be able to use it at any moment, to obtain the results they want to achieve. When you apply this technique regularly, you do see the world differently.

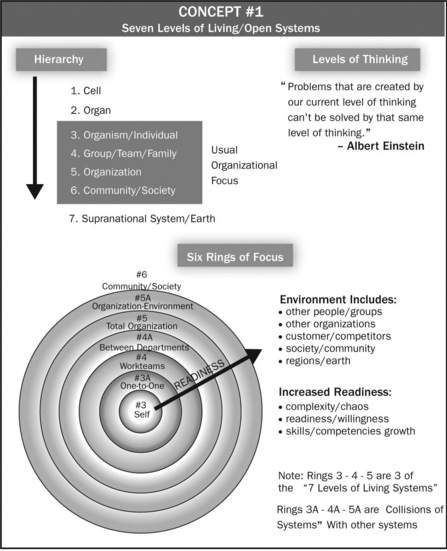

Concept 4 – The Rollercoaster of Change

The fourth major concept of the Theory of Systems Thinking, which is outlined in Figure 5.4, focuses on what happens when individuals and groups are faced with imminent change. It is a model that may seem very familiar – probably because you have lived it more than once. However, did you understand what was occurring and why you were feeling the way you did?

Although we call this model ‘The Rollercoaster of Change’, I have started to add the word ‘emotional’ because I really do believe it is ‘The Emotional Rollercoaster of Change’ that we experience. And that’s what makes it so hard for some leaders and managers to deal with – they have to develop a degree of awareness and sensitivity to the emotional feelings of others. That is difficult for some people to understand and even harder for them to develop the required abilities. Some organisations even go so far as to discourage managers from becoming too close or too personal with their staff and colleagues. I believe this is driven by a fear of inappropriateness, given the frequency with which reports of abuse are being reported. We are not talking about that type of closeness. We are talking about a solid degree of humanness. There is a great difference between these two perspectives.

For me, the issue of ‘emotions in the workplace’ is a no-brainer. To pretend that they have no place at work is to deny one another’s humanness. The challenge is to determine how to face each other’s emotions and use them in a way that helps the individual and the organisation.

The importance of this aspect of good management was vividly reinforced for me in 1991 when I was serving as the Executive Director of the Staff Development Division of the Saskatchewan Public Service Commission. I had always believed that being close with your staff team was an extremely valuable characteristic of a good leader. During one of the regular management development programmes that we conducted regularly for senior managers and executives, I made reference to this personal belief and it generated much discussion, with a variety of points of views being expressed. No resolution was reached during the session as to what was the best way to handle emotions within the workplace.

About a week later, one of the participants sent me a copy of a book by James A. Autry, entitled Love and Profit: The Art of Caring Leadership. At that time, Autry was the President of the magazine group of the Meredith Corporation, based in Des Moines, Iowa. They published dozens of popular monthly magazines such as Better Homes & Gardens, Ladies Home Journal and Metropolitan Home. Just so that you don’t get an inappropriate impression of Autry, it’s also important to note that he was a former Air Force jet-fighter pilot. His book is a collection of short essays on poignant topics and poems that he has written to describe a situation he has encountered. He describes himself as a ‘business poet’.

In this book, he writes passionately about some of the most difficult aspects of being a good manager – how to deal with an employee facing a second mastectomy operation, because ‘they didn’t get it all the first time’, how to deal with having to terminate an employee and doing it with a sense of care and concern, rather than anger, or how to keep staff motivated when a colleague has to spend extra time at the hospital dealing with a loved one who is dying. As he points out, ‘They don’t teach you these things at business school and the answers certainly aren’t to be found in any personnel manual that I’m aware of’.

In his essay, entitled: ‘It’s Not Just Okay to Cry, It’s Absolutely Necessary’, he writes:

‘Several years ago, I was on a panel with a well-known management consultant in the publishing business. It was at the time when a lot of women were first coming into advertising and advertising sales.

A middle-aged man asked the consultant, “What do you do when you are appraising or criticizing a woman and she starts crying?”…

Implicit in the question of course, were a couple of things: One, the man implied that crying was somehow outside the rulebook, not allowed, not legitimate, thus its possibility justified whatever residual resentment he felt for women being in his business to begin with. And two, he implied that a crying employee created a management situation requiring some kind of special training.

The consultant had an answer: “I keep a box of Kleenex in my office,” he said, “and when a woman begins to cry, I just take out the box, put it in front of her, and leave the office until she regains control.”

Please understand that I did not make up this quote to fit this essay. The man actually said it.

So I asked, “What do you do when a man cries?” Everyone laughed, thinking it was a quip. And my question never was answered.

The big-time consultant was wrong with his run-and-hide technique. He was wrong then, and he sure as hell would be wrong today.

Consider this: If you don’t think people, including you, should be able to cry about the job, then you don’t think work is as important as you say it is.

The subject, of course, is not crying but expressing emotion.

But let me make something clear: I’m not talking about management for and by wimps. In fact, I am talking about the most difficult management there is, management without emotional hiding places.

You can no longer be the tough guy, and you also can’t come on as the impassive, icewater-in-the-veins “cool head”. On the other hand, the kindly parent who listens-and-does-nothing approach also won’t work.

No, in every situation, you must lead with your real self, because if you’re going to be on the leading edge of management, you sometimes must be on the emotional edge as well.’3

This book certainly caught my attention. Autry was speaking about the very things that were considered to be taboo topics in many workplaces. Here we were trying to design and deliver management development programmes for the leaders of the future within our organisation. It seemed appropriate to share Autry’s thoughts first with the current group of leaders, as well as those enrolled in our senior management development programme. So, I purchased sixty copies of the book and sent a complementary copy and a short letter of explanation to every Deputy Minister and Assistant Deputy Minister in the Government of Saskatchewan, and also to our programme participants. In Canada, we follow the British model of government, in which the Minister is the member of Cabinet responsible for a particular Government Department Portfolio. The Deputy Minister is the senior staff member of a Department, reporting directly to the Minister, and each Department could have anywhere from one to three Assistant Deputy Ministers, each with responsibility for a specific programme area of the Department.

We received more positive feedback from this group of senior managers over this simple initiative than any other initiative we conducted over a three-year period. Apparently we had touched a nerve. They commented on the appropriateness of the topics and the sensitivity with which the topics were presented. They stated that it helped them to realise the importance of the relationships side of their responsibilities as senior leaders and many acknowledged that they had been using ‘emotional hiding places’ as part of their management style, and now understand the short-sightedness of this approach.

What this lesson taught me was that in our own organisation, as was the case in many other organisations I’m sure, we needed to spend more time helping employees understand that there was indeed room for emotions in the workplace. After all, that would help to humanise the workplace, when people begin to understand that others truly do care about what is happening to their colleagues and are usually quick to offer support. When you examine the results of the ‘Great Places To Work Research’ (this model was outlined in Chapter 2) two of the most important characteristics of the organisations that receive the highest ratings each year are: that there is a sense of family or team and also that people in these organisations demonstrate a strong sense of caring about one another. Feeling free to show one’s emotions along with people who have developed the sensitivity to deal with these emotional situations in a responsible, caring manner are the hallmarks of every outstanding organisation we have studied.

It may seem like we are a long way removed from where we started this section, which was to explain the elements of the Rollercoaster of Change. The story just outlined relates directly back to this concept and it was clearly demonstrated about a year later when we were faced with an extremely challenging change assignment – a large corporate downsizing initiative to help us cope with major budget pressures. But, before we share the results of this initiative with you, let’s look at the components that make up the Rollercoaster of Change.

The roots of this model come from the work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, MD, in her book On Death and Dying, in which she describes the five stages that a person experiences when dealing with their own death, or for their family members who are trying to cope with the loss of a loved one.4 It is easy to understand that death is one of the most profound changes that any of us will experience – whether our own, or that of another loved one, close friend or close colleague. We have adapted Kübler-Ross’s concepts to reflect what happens in a situation where the individuals impacted by the change continue to carry on living in the situation in which the change occurred. In this respect, it more closely resembles what an individual experiences when a family member dies, rather than what the dying person encounters, which was the primary focus of Kübler-Ross’s research.

In the Rollercoaster of Change Model, there are four specific stages that individuals go through. Remember from the Seven Levels of Living Systems that change begins with the individual and then spreads outward. These four stages describe how an individual copes with change. The group’s response to change is the culmination of the individual change processes experienced by the members of the group.

The process flows in the model from left to right. The top left of the model indicates the point at which the change announcement is made. In the case of a fairly drastic change, for example a major budget cut that requires every department within an organisation to pare back their budget requests, these are the stages that people will experience.

Stage 1: Shock and Denial

People will demonstrate surprise and disbelief when they first hear about the change announcement. They will challenge anyone who shares the message with comments such as: ‘Where did you hear that?’ ‘I don’t believe it.’ ‘They can’t be serious – do they really think we can do that?’ This stage of shock and denial will persist until they have verifiable proof that the change is indeed going to happen. Once they are convinced that the change is unfolding, like it or not, they will move to the next stage.

Stage 2: Anger and Depression

In this stage, as an individual now knows that the change isn’t a rumour or that it is not negotiable, they slip into a stage of rebellion. They become very discouraged and upset. They make comments like: ‘Well, that’s gratitude for you. I’ve given them fifteen years of dedicated work and this is how they treat us.’ ‘We can’t possibly work within those parameters – we might as well shut down the operation.’ ‘I don’t know why I even bother to come to work each day when they expect us to work under these conditions.’ During this stage, you will see and hear a lot of venting of emotions, and it won’t be pretty. Depending on the degree of upset being experienced by an individual, this stage can persist for a brief moment of frustration – or it can last for weeks and months. Obviously, the longer it persists, the degree of residual damage increases.

Stage 3: Hope and Acceptance

People move from stage 2 to this stage only when they realise that they do need to pick up the pieces and move on. They don’t enjoy being in a perpetual state of anger and they at least reach the stage where they are now prepared to try to get on board with the change. You’ll hear comments such as: ‘Well, I’m still not sure this is workable, but I’ll give it a try.’ ‘It will be tough, but I guess if we have no other choice, we’ll have to figure out a way to make it workable.’ ‘I’ll give it a shot – but I’m still a bit sceptical.’ As individuals enter this stage, they begin to sense a glimmer of possibility – and it’s a much better feeling than they had when they were stuck in a state of anger and despair. That is one of the great characteristics of humans – they have a belief that they can overcome adversity and rebuild their lives. We see this over and over again following a major disaster such as the tsunami that hit Indonesia on Boxing Day in 2004 or Hurricane Katrina that hit New Orleans in August 2005. Even in the most trying of situations, people do eventually begin to rebuild their lives – and it can only occur when an individual decides that they can no longer continue to live with the pain of their status quo, so they decide to make improvements for themselves. Ironically enough, once an individual reaches this stage, they are surprised at how much support there is from others, to help them cope with the challenge of adjusting to the new situation.

Stage 4: Rebuilding

Once individuals have worked through the adjustments needed to successfully navigate stage 3, they find themselves re-focusing on creating their new reality, in the new world of change. At this stage, individuals will be sharing ideas and information with others about how they coped with the adjustments needed to ‘get through the change cycle’. They have accepted that there really is ‘life after the change’ and they also begin to see ways in which their situation is manageable again, in spite of the change. That’s not to say that everyone is totally pleased with the change. However, they have been able to reconcile their emotional resistance and have reached a stage where they can tangibly see that life in the new reality can be okay. Using the budget cut example, people recognise that some of the things that they eventually had to cut were really marginal activities or programmes and they can see how the re-allocation of funds is better now as a result of the pressure to change. They see that the trimming process has its own benefits, because the group is more focused now and also more committed to prove that they can still provide a valuable service, in spite of the constraints. They can now also see how the collective efforts of the staff of each department have started to produce benefits for the whole organisation, as anticipated, as the fiscal situation becomes more manageable.

Now, although we walked through these four stages in a nice, clean linear sequence, it often doesn’t work that smoothly in real life. That’s because we are dealing with people who have strong emotions, strong feelings and strong beliefs. They are also trying to change their practices and habits and, as we all know, changing habits is not a simple task at the best of times. So, don’t be surprised if slippage occurs. This is most common at stage 3, as people begin to move up the right-hand side of the curve. Individuals are quite vulnerable at this point and the smallest setback can send them crashing back into anger and despair, as they say: ‘See, I knew this would never work!’ ‘I don’t know why I bothered to try and go along in the first place.’

The ‘Hang In’ Point

Let’s step back for a moment and look at the full change cycle. You’ll notice that there is a phase at the very bottom of the curve that we haven’t talked about yet. We have labelled this as the ‘Hang-In Point’. As anyone who has ever dealt with someone who has struggled with a major addiction, such as tobacco, alcohol, gambling or obesity, counsellors will readily point out that in a serious situation, an individual needs to ‘hit bottom’ before they will ever be ready to accept any help to move forward. This may seem harsh, but it does reflect the reality of life. Advice and support offered before a person bottoms out is usually wasted and lost. Why is this the case? Because no one can help another person until that person is ready to help himself or herself. Up to this point, the pressure for change was a ‘given’ – it was given to them, they didn’t ask for it, nor did they really want it. That’s why they have been resisting the change through stages 1 and 2. This is the pivotal point at which personal motivation must kick in – and it can only do that if the individual can find a suitable answer to that famous WIIFM question – ‘What’s In It For Me?’.

For this reason, we need to understand that the right-hand side of the curve – towards the new future state – is optional. It’s up to each individual to decide for himself or herself how they want to respond to the change that has been introduced.

Once an individual can begin to see some possibility in the new future state, that seems to be better than what they have been dealing with, then their motivation shifts and they are in a position to begin the rebuilding process. In fact, at this stage, individuals face three options:

1. Get on with the change and initiate re-building by starting up the right-hand, optional side of the curve, having identified a good answer to the WIIFM question.

2. Quit and leave the organisation. For some people, they just cannot accept the new future state and so they decide to resign their position and leave the organisation. This is actually a very healthy option because if they cannot see what’s in it for them, they will never be satisfied with the new situation. By resigning and leaving, they move to a new career option in which they do see possibilities for their own future. Now they are on a new rollercoaster of change, but in this case, they are the architect of the change, not the victim of change as they were in the old situation. When this person exits, it opens the door to engage someone new to join the organisation who does agree with the new future state and is willing to help make it happen. This becomes a win-win situation, when it is handled properly.

3. Quit and stay. This occurs when an individual does not have the courage to leave the organisation, for any number of reasons – but they are also adamantly opposed to the change and will not move to stage 3. They quit and stay. This individual is a cancer for your organisation. They will not help you to move forward. They will also try to enlist others to commiserate with them and reinforce the belief that the change was not needed and should never have been introduced. Now you have an internal war occurring and people begin to pick sides, all at the expense of the change initiative. We’ll explore options for dealing with this situation later in this chapter.

This cycle of the Rollercoaster of Change outlines the various emotional stages that people go through when dealing with a significant change. As change can only be effectively implemented once enough individuals decide to reinforce the change and support it, how can leaders and managers help to ensure that a critical mass of the individuals who need to make the change do indeed make it to the rebuilding stage?

There are specific behavioural responses that ‘change managers’ can employ to help make this transition a successful one. By ‘change manager’, we are not necessarily referring to someone in a formal management position. A change manager can be a colleague, a co-worker, a spouse or a friend. The change manager is someone who cares enough about the individual to offer support to help the other person to manage the change for himself or herself. This person serves as a guide or aid on the journey of transition from the current state to the new future state. What are these behaviours that can provide the type of support needed?

At each specific stage of the Rollercoaster of Change, a change manager can be very helpful if they provide the type of support that an individual needs to be able to move forward to the next stage. To be able to do this, the change manager needs to have a good understanding of how the individual is really feeling at each stage of the transition. Let’s revisit the various stages again, only this time we’ll focus on the actions of the change manager.

Stage 1: Shock and Denial – How to Respond

In this stage the individual faced with the new announcement about the pending change is confused and uncertain about what is really happening. They need clarification that the change is indeed happening and they also need information about the scope and magnitude of the change. So, if that’s what is needed, a good change manager must become an information provider. You will need to be able to confirm indeed that the change is occurring. You will need to be able to explain the significance of the change. You will also need to be able to outline the rationale for the decision to introduce the change – even if the individual is unlikely to remember any of this information in the early stages. That is a reality because the individual’s personal sense of self-preservation and survival means that they focus on their own needs first, not those of the organisation. If the change manager’s primary role at this stage is to provide accurate information, then their behavioural response is to be a good teller. You need to be able to tell people what is happening, why it is happening and what it means to each one, as well as the organisation. Communications theory reminds us that important messages may need to be repeated as many as four or five times, before they are fully received by the target audience. Some leaders have trouble accepting this fact. They assume that ‘once I’ve told them, they know’. Repetition of the message is very critical here so don’t put your megaphone away prematurely. If your organisational structure is such that people are spread out in several different locations, then you will need to ensure the message is available in various media formats – some may receive the message verbally, first hand, while others may receive the message via video conference or taped message, or through some form of written communiqué. The multiple formats must be highly congruent so that the various message formats don’t end up contradicting one another, creating confusion and chaos. And they must be repeated as many times as it takes until you are sure that everyone has the new message. It’s impossible to over-communicate during major changes. If an individual has not understood the message, they cannot move out of stage 1. Once the person clearly gets the message they shift and move forward.

Stage 2: Anger and Depression – How to Respond

In this stage, now that it is clear what’s unfolding, an individual needs to release any strong feelings that they have about the change. They need to vent, to unload their emotional energy. They don’t want someone to try and provide rational advice at this point. They don’t want to be told anything in fact. What they really need at this stage is someone to be a good listener. That’s all: just someone who will listen to their concerns, their anxiety, their fears, their disappointment and their frustration at what is happening. At this point they have no sense of control, which is always very disturbing for anyone. Unfortunately, what most people tend to do when someone describes how bad they are feeling during this stage is respond with ‘You shouldn’t feel that way.’ But they do! And by telling them that, you are not listening, which is what they need. It is very hard for most of us to sit patiently and quietly and let people unload. Our desire to help kicks in and we end up providing an inappropriate response, which drives the individual deeper into depression. We are generally not good listeners, particularly during stressful periods. Yet, that is exactly what is needed the most. In our workshops covering this methodology, I have had people ask: ‘How do we know when they are done venting?’ Generally you will hear the individual make a comment that sounds something like: ‘Whew, I just don’t know what to do next!’ That’s your opening. That’s their request for guidance and support. Now they are ready to listen again. Prior to this point, any advice you can offer will fall on deaf ears. Now it’s time to shift to stage 3.

We’ll come back and revisit the ‘Hang In’ point response techniques a bit later.

Stage 3: Hope and Acceptance – How to Respond

The best way to engage someone in a stage 3 conversation is to ask if there is anything about the new future state that they believe might be an improvement on the way things used to be. It may take a little while for them to acknowledge any potential benefits that might provide a reasonable answer to the WIIFM question. Don’t forget, they have just spent a considerable amount of time and energy trashing the need for change. Don’t expect them now to embrace it with open arms. It will be a gradual process for most people. When they are able to begin to see how there might be some possible improvements, you need to become a good coach and help them to uncover specific things that they can do in their own day-to-day activity to begin to adjust to the change and help to move it forward. Be ready to praise and acknowledge constructive efforts in the desired direction – even if they are not totally successful. Recognise and reinforce the effort. Through continued support, the individual will slowly but steadily become more comfortable with the changed behaviours that are required to contribute to the successful implementation of the change. As they begin to feel more comfortable with the changes – and more valued for doing so – their commitment will be solidified.

Having said this, you need to be aware that in this stage, it is not uncommon for people to slip back. The metaphor that best describes this is to imagine yourself driving a car and you end up stuck in the mud or the snow. As you try to move forward, you slip back because you do not have enough momentum to get out of the rut that you are in. So, you have to begin to rock forward and back, forward and back until you have generated enough energy to overcome the restraining forces and you come out of the rut and start moving forward again. Good coaches help people to learn how to navigate when they are stuck in a rut.

Stage 4: Rebuilding – How to Respond

Once an individual reaches this stage, they are on a roll, making solid progress on their own. They have already begun to see the benefits of the new future state and they are contributing to achieving more of the benefits, as they and others work diligently to achieve successful implementation of the change. Because they have achieved this level of adjustment, they can be very helpful as coaches and guides for others who are still working through the various stages of the Rollercoaster of Change. The appropriate change manager response at this stage is to delegate and celebrate. You delegate some new responsibilities to individuals that acknowledge their willingness and readiness to help achieve successful implementation of the change. You celebrate the small victories, the fact that a small group of individuals have ‘come on board’ with the change and are contributing to success. Too often in the throes of change, we focus on those resisting change and fail to show appreciation for those who embrace the change. They are the force that will carry you forward to the new future.

The Hang In Point – How to Respond

As we saw in exploring the behaviours of individuals at each stage of the Rollercoaster of Change at the beginning of this section, individuals who were stuck in this phase needed some special attention. Therefore, it stands to reason that the role of the change manager also requires some special skills to be able to help an individual cope with this phase.

For people stuck in this phase, we noted that they have three choices – move forward, quit and leave, or quit and stay. From the change manager’s perspective, the first two options are acceptable and support can be readily provided to help an individual – because they have already made their choice. You can enable them to move to the rebuilding stage or you can support them as they seek other employment opportunities outside of your group, submit their resignation and move on to the next chapter in their career, with honour and dignity.

For those who prefer the ‘quit and stay’ option, you need to apply a considerable dose of ‘tough love’. Because individuals who are in this state of mind are constantly seeking others who will agree with their views about the impending change, they are a constant source of resistance. As they are searching for others who will commiserate with them, they can become a growing negative force as you work hard to move forward. While they are in this state, they will not be able to carry out their day-to-day responsibilities effectively, which further compounds their negative impact on the organisation.