5

Ethnography of Speaking

The Ethnography of Speaking (EoS), also known as the Ethnography of Communication, is one of the first clearly articulated frameworks to approach the question of intercultural discourse and communication. Dell Hymes is recognized as the originator of this field, based on a series of writings beginning in 1962 (for example, Hymes 1962, 1964, 1972, 1974). In this chapter, I outline the basics of the original Hymesian EoS approach and its significance, and then discuss some studies that take the general EoS view but elaborate on methods or theory. I then compare two examples of EoS analysis in order to show how such a comparison can be profitable for studies of intercultural discourse and communication.

Hymes’s work arose in an intellectual climate with two important currents of thought, although undoubtedly they are not the only ones. The first was Chomsky’s generative grammar program (originating with Chomsky 1957 and 1964), and second was the emergence, and deep discussion, of methods for description in anthropology, and the structuralist focus of the time (Lévi-Strauss 1963). Hymes outlined two main goals for his program, a descriptive and a theoretical. The descriptive goal was to develop a framework with two purposes. First, the framework should reflect the ways in which native speakers understand interaction within their cultures. This is an “emic” description, similar to the “phonemic” descriptions made for sound systems of languages. At the same time, the framework should be able to be used to compare the ways of speaking used by different cultures for the same or similar speech events. This is an “etic” description.

Theoretically, Hymes pointed the field to a goal of modeling and theorizing communicative competence. This term is a deliberate reaction to the strictly grammatical competence that Chomsky’s generative theories were meant to model. In Chomsky’s view, linguistic competence is the knowledge that someone has to be able to produce all and only the grammatical sentences of their native language. For Chomsky, what is actually said, and how, and why, is the purview of performance which generative theory does not address. Hymes’s only slightly joking response to this view is to point out that a person who randomly generates all and only the sentences of their language would not be understood by other native speakers of that language as a competent speaker. Thus, a general theory of language ought to include not just linguistic competence but the competence of a speaker to use the appropriate language for a particular situation. The theory is organized by first determining how to describe “the appropriate language,” and how to define a “situation,” and how to relate these notions to a “culture.”

Hymes observed that speech was organized and related to culture on a number of levels: the speech community, the speech situation, the speech event, and the speech act. The speech community is a concept that has been discussed and debated extensively in the years since Bloomfield (1933) first proposed the notion and since it was taken up by Hymes (1974), Labov (1966), and Gumperz (1968) (for an extremely helpful overview of the concept, see Patrick’s 2004 discussion of the concept in variationist sociolinguistics). Hymes’s view of the speech community is that it is “a community sharing rules for the conduct and interpretation of speech, and rules for the interpretation of at least one linguistic variety” (Hymes 1986: 54). The most important part of this definition, which is a feature in almost every other definition of speech community as well, is the insistence that there is a sharing of rules, or norms, for both the conduct and the interpretation of speech. This idea is important because the notion that we can describe this normative behavior is at the heart of the EoS. While the notion of speech community is not one that is often highlighted or problematized in EoS studies, it is nevertheless an essential background idea for most work that might fall under this rubric, although the speech community under description is usually assumed rather than demonstrated. For example, in the examples below the two social entities (a Kuna village and an American fraternity) are both assumed to be speech communities, although they are arguably quite different kinds of things. However, under the criterion of shared rules for use and interpretation, they fit quite well. Hymes argued that “the essential thing is that the object of description [the speech community] be an integral social unit” (Hymes 1986: 55).

A speech situation is an activity that is “somehow bounded or integral” (Hymes 1986: 56), but doesn’t necessarily require speech, or rules for using speech. However, Hymes includes it in his descriptive framework because such situations might have an impact on the ways of speaking used by participants in these situations. For example, a sporting event such as a swim meet is a situation that at times has some language (to announce the events and start the races), but the event itself is not tied to the use of speech, because the essential part of the event is swimming and not talking. A speech event, on the other hand, is a bounded event that is “directly governed by rules or norms for the use of speech” (Hymes 1986: 56). Some culturally recognizable way of speaking is thus part of the definition of the speech event. A speech act is, in a sense, the subatomic particle of EoS: it is a minimal unit of speech that accomplishes some action: question, request, order, threat, compliment, etc. In “classic” approaches to speech acts (Austin 1962; Searle 1969), speech acts are formally described and coterminous with single utterances, but since EoS is interested in how native speakers recognize and create speech acts, it recognizes that such acts can require multiple turns.

The three levels of description are nested so that speech events are made up of speech acts and can in fact help define what the speech event is. Furthermore, several different speech events may make up a speech situation. Hymes gives the example of a party, a conversation at the party, and a joke in a conversation at the party as an example of how a speech situation contains speech events which in turn contain speech acts. Readers may encounter other terms for these ideas which are similar. For example, Levinson’s (1979) activity type is similar to a speech situation, although Levinson contrasts it with speech event. Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (2003: 98) discuss speech activities, which are similar to both speech acts and speech events; however, they are not necessarily bounded, and can be used in a number of different speech events. For example, lecturing is a speech activity, while a particular lecture (at a specific day and time) is a speech event; lecturing is something that is usually done in lectures, but in the US it is not the only thing (questioning might be another), and we might find lecturing in a different speech event, such as an interview (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet’s speech activities are very similar to the genre category I discuss below).

From the beginning, the EoS approach assumes different ways of speaking in a speech community, and one of the goals of description and theory is to understand how and why those ways of speaking are deployed by speakers. It is important to note that this view is one that differs from most other views in linguistics, including variationist linguistics, because it acknowledges at the outset that there will be distinct systems of language, used by different speakers in various situations but all occurring in the same speech community. The vagueness of the term “ways of speaking” is thus deliberate, as these different ways might be classified in other theories as styles, registers, varieties, grammars, and even languages. EoS takes a more agnostic view about the status of different ways of speaking, seeking rather to discover how the speakers in the community understand the different “ways of speaking”. For example, a community may assume that there is a dialectal rather than a language difference for mutually unintelligible ways of speaking (as is true for many dialects of Chinese), while another community may view mutually intelligible ways of speaking as different languages (as for Bulgarian and Macedonian or Serbian and Croatian). EoS would want to describe when these languages are used and by whom, and why they are considered different languages or different dialects. Hymes proposed a framework or heuristic for these sorts of descriptions, which I explain in the next section.

Canonical SPEAKING “Grid”

Hymes’s heuristic took the form of a mnemonic based on the components of the speaking grid, as follows:

Setting

Participants

Ends

Act sequence

Key

Instrumentalities

Norms

Genre

I’ll explain each of these in turn before setting out the example analyses.

Setting is composed of two very basic aspects of the speech event. First is the physical setting, including the place and any other relevant descriptions, especially if such an event depends on aspects of the physical setting. For example, a trial takes place in a court room and only under very special circumstances can it be held elsewhere. On the other hand, weddings in the US are often held in homes, in hotels, and outdoors, so the setting is not as essential for the definition of the speech event (although this varies depending on the religious subculture). The scene is a descriptive idea that Hymes says is the “‘psychological setting’ or the cultural definition of an occasion as a certain type of scene.” So one needs to describe the emotional aspects of the setting, and in fact a scene could be described by the main speech act. A trial is a serious event potentially determining the direction of someone’s life. A wedding is a festive scene that celebrates the changing of a culturally significant relationship between two people (and, depending on the culture, their families and clans).

The participants are people who need to take part in the speech event. This will not identify individuals by name, but by role or status or station. The named roles, etc., of the people will describe culturally relevant people, especially for the speech event, so that in the norms of interaction it will be specified how they are supposed to act in the event. For example, in a trial in the US the participants are at minimum a judge, a person bringing the suit (plaintiff or prosecutor, depending on whether the trial is civil or criminal), and a defendant (for both kinds of suits). Other categories are: lawyers for both sides, witnesses, bailiffs, members of the jury, court reporters, clerks, and spectators. Weddings have similar definitions of roles, depending on the culture.

Ends are the purposes involved in the speech event. On one hand, there are the outcomes of the speech event. For example, the conventional outcome for a trial is a verdict. On the other hand, there are goals that the participants have for the speech event. So in a trial, for example, even though a prosecutor and a defendant want the outcome of the trial to be a verdict, they each want a different verdict and thus have different goals.

Act Sequence is the description of the central aspects of the speech event, in terms of both form and content. First is the message form. Form here does not mean the language or dialect or variety that the event is conducted in. Rather, it is other stylistic factors and choices. For English, we would want to note how much “directness” is expected. Message content is more clear, encompassing both referential content such as the topic of the event and also the speech act content of the event, including the ordering of acts in the event. Here it is worth reminding the reader that these descriptions are idealized expectations of what happens in these events, and in most cases a particular event will deviate from what is listed here at least slightly. It is also worth noting again that when deviations from the norm do occur, they are often visibly or audibly noticed by native speakers and thus tell us that a deviation of some sort has occurred.

The Key describes the “tone, manner, or spirit” of the event (or of the different acts in the event). Thus we will want to know whether the tone is serious or joking, or playful. This key is the overall emotional tone or feeling of the event or part of the event, and as such there is no single list of such keys. Rather, its identification depends on the types of emotion that the culture recognizes as significant or important.

Instrumentalities describes the way the speech is normatively produced. The Channel describes whether it is oral or written. Within the channel, we also want to specify the mode – speaking, singing, humming, chanting, and printed, written, or electronic (and perhaps, within electronic, what form of electronic as well). The forms of speech are the expected language, variety, dialect, register, code from the verbal resources or repertoire of a speech community. Note that we could suggest that this is also a part of the message form, depending on whether we look at varieties as “instruments” or “styles.”

The description of Norms is generally what takes up a major portion of any ethnography of speaking, and could be argued to be the central issue. Hymes identifies two sets of norms. The first set is composed of norms of interaction, which are basically “rules” of how interactants are supposed to behave, for example, who should talk and when, how turns might change. This description is potentially quite expansive, given that there could be such norms for many things that might happen in a speech event (how to sit, whom to look at, when to speak, etc.). Norms of interpretation are even more expansive, because often such interpretations depend on the history, ideologies, and practices shared throughout a culture. So an ethnography of speaking in a sense presupposes a more general ethnography of the culture in which the speech event takes place.

Finally, Hymes listed the Genre of the speech event as an important part of an ethnography of speaking; he provides examples such as “poem, myth, tale, proverb, riddle, curse, prayer, oration, lecture, commercial, form letter, editorial” (1986: 65), based on “formal characteristics traditionally recognized.” This category is a little less clear, but seems quite similar to the speech activities discussed by Eckert and McConnell-Ginet. There are two main points to pay attention to with genres. First, the category is about formal features of an event. For example, the difference between a poem and a novel is not necessarily the content (both could have as their subject a single day in Dublin, for instance), but the form that these take. Second, and more importantly, these formal features are different from that of the act sequence because genres are recognized and named by the culture and they are “transportable” from one event to another. Thus one can insert a bit of poetry into a novel and know that it will be recognized as such by a reader. In talk, one can insert a “lecturing voice” (seriously or in jest) and if it is done the right way, interlocutors will recognize it as such. When describing message form for the speech event, we are simply describing what is expected for the single speech event, while a genre is something that allows us to generalize over a number of speech events.

This grid is really only a guide – a heuristic or checklist – for a real ethnography of speaking. Most full ethnographies of speaking require a more extensive treatment that includes all of these elements but does not necessarily list them in this order. One of the examples I will discuss below summarizes an entire book which is an ethnography of speaking of only a few speech events of the Kuna people of Panama (Sherzer 1987).

How can EoS be applied to Intercultural Discourse and Communication (IDC)? One of the strengths of the EoS is in the heuristic “grid,” which gives us a kind of checklist of the kinds of things to look for when we are looking at communication between people of different cultures. If we focus on one speech event in two cultures and work to create a speaking grid, we are forced to look for differences (and similarities) where we might not otherwise think to look. The rest of this chapter provides an example of such a comparison.

Gatherings in Two Cultures

Kuna gatherings

Intuitively, the two cultures I will discuss seem to have very little in common. But we will see that many commonalities emerge once we are forced to list all the parts of the speech events I am comparing. This rigor in comparison is one of the strengths of EoS, comparable to many methods of social-scientific comparison that end up showing that, while we initially may focus on differences, once a complete comparison (or a quantitative one) is performed, such differences are largely attributable to our habit of simply not noticing similarities. I’ll first describe each community and culture in a roughly narrative description of the event, and then compare them through speaking grids.

I’ll draw on Sherzer’s (1987) monograph on the Kuna of Panama for the first half of the comparison. The Kuna live on the east coast of Panama and are organized around small, dispersed villages. At the center of each village is a “gathering house,” at which different kinds of gatherings are held at the end of each day. These gatherings vary in who participates and in their importance, but it is in the gathering that most of the business of the village (and the Kuna people) is done. It is the venue for judicial proceedings, entertainment, and communication among villages. These gatherings are held at the “gathering house,” a large circular hut located in the center of the Kuna village. While there are smaller gatherings daily that may only include a few of the village elders, Sherzer suggests that these are understood to be derivative of the more elaborate gatherings held once or twice per week. The central activity of such gatherings is the “chanting” by two “chiefs” – two are required because one “chief” must respond to another for the chanting. The “chiefs” (or saklakana, of which “chief” is only a rough gloss) are literally central, because the gathering house is circular and the chiefs sit at the center on two hammocks, side by side. Near them is a “spokesman,” and at a further remove surrounding the chiefs and the spokesmen are the men of the village, and finally the women of the village in the outer ring. There are “policemen” who make sure that everyone stays awake and listens.

Before the chanting, there may be some other business, and then the chiefs begin their chanting. They speak in a special “chief language” which is a derivative of the everyday Kuna language. In general, it has more elaborate morphology and some slightly different word order. One chief is the main chanter, while the other simply responds (Sherzer translates most of these responses as “indeed”). The topics of the chants are varied, from stories of local people, to myths, traditional stories, histories of the Kuna people, and stories from the Christian Bible. These stories are meant to teach and provide a common history and set of beliefs for the community, and Sherzer suggests that they are important in maintaining the cohesion of each village and especially the cohesion of the wider Kuna speech community. Once the chiefs have finished chanting, the spokesmen reinterpret the chant in everyday Kuna language, and may add commentary about what lessons should be taken from the stories told. There may then be another chant from the second chief.

Description of fraternity meetings

The “gathering” that I will compare to the Kuna gathering house is a meeting of a college fraternity in Northern Virginia, USA, which I observed in the early 1990s (Kiesling 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002). Although these speech events may not seem similar at first, the parallels between the fraternity meetings and the Kuna will become evident, especially after the speaking grids are compared.

Fraternities are social and service clubs which select their members from among male undergraduates at universities in the United States. Most were started in the nineteenth century as literary societies, and evolved into social outlets. At many universities, fraternities have houses which are the center of fraternity life. These houses function as dorms, meeting halls, dining halls, and social halls. At Lee University where I did participant observation,1 however, fraternities did not have houses on campus. Nevertheless, for many members the fraternity becomes the center of social life. Members live with each other, take classes together, compete on the same athletic teams, and organize social functions together. In many ways, the fraternity is organized around a model of a close family; members are known as “brothers,” and the collective members of the fraternity are often referred to collectively as the “brotherhood.”

While the fraternity appears as a single social unit, there are several ways that members distinguish each other internally. The most important is a man’s membership status. Fraternity members organize themselves as a group with an inner core or members, and members that are ever more distant from the center. At the outside of the membership circle are non-members who want to become members, or who the fraternity wants to convince to become a member. During the University-sanctioned rush period, these men become “rushes,” as they move closer to membership. Once the rushes have been invited to join the fraternity, they are “pinned,” and they become pledges. They are not yet members, but if they pass through the period of pledging successfully, they will become members. At the end of pledging, prospective members are initiated formally and technically become full members. However, they are “neophytes” or “nibs” (derived from the acronym for “newly initiated brothers”), and are seen as having little knowledge or ability to do all but the most mundane jobs for the fraternity. In becoming members they have moved closer to the center, but they are still far from it. After being in the fraternity for at least a year, and perhaps serving in a few minor offices, the members are regarded as full members, and when members become seniors (about to graduate from the university), they have the most privileges with the fewest responsibilities, since they have “paid their dues” for the fraternity. These senior men are the most respected alongside the recent alumni who are still involved in the fraternity. When I did my fieldwork, there was one alumnus (“Pencil”) who was with the fraternity often and helped them with advice and financial support. He was the most admired of all the members, as he had the weight of history, experience, and age, and was also active in the national fraternity.

There is also an informal distinction between the formal, governing, “business” sphere of the fraternity and the social sphere. The border between these two spheres is fuzzy, since older, office-holding members tend to associate together, and personality plays a large role in who is elected into fraternity offices. But the difference between the two is nevertheless real, at least in the minds of the fraternity members; almost every member I interviewed mentioned this separation. What is fraternity “business”? Some business is organizing philanthropic activities, such as putting on a charity fundraising event or co-ordinating who goes to what school when in the adopt-a-school program. But the vast majority of the “business” is focused on facilitating the social sphere of the fraternity. Most dues paid by the members go to pay for parties and other social events, and members organize fundraising events that only benefit the fraternity.

In addition to age/membership length and office-holding, another way the fraternity is organized, especially socially, is by pledge class. Each group that is admitted at the same time (usually once a semester) is identified as one pledge class. Pledge class members also are usually of similar age, because men usually join the fraternity in their first or second year of college. Thus, the pledge classes become “stratified” by age, with members of older pledge classes usually holding higher positions than others. While there is no formal assignment of privilege to older members, they feel they have the respect of younger members. This respect is illustrated by the fact that older members speak more in open discussions than younger members do (and that as members become older, they become more vocal).

The only time all members gather to discuss the “business” sphere of the fraternity, meetings are also the most formally organized activity in the fraternity.2 The meetings have a set format: they begin with reports from all of the officers, followed by discussion of any important issues, possibly with a vote. The meetings are governed (loosely) by parliamentary procedure. The meetings are “formal” in that there is an explicit rule that one member has the right to the floor at a time (although this rule is often broken), and the president serves as chair. In terms of purpose, the “business” aspects of the fraternity are the topics of meetings, so a member’s office and age – his structural power – is more salient than in other speech activities.

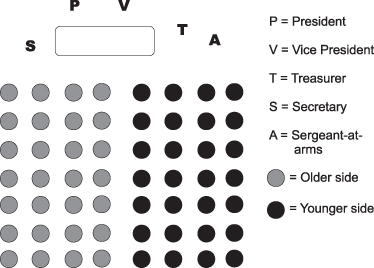

Structural power is highlighted by how the members sit in meetings. All meetings, except ritual meetings, are held in the same classroom on Sunday evenings. Several members of the Executive Committee sit at the front of the room, facing the members, with the president and vice-president at the center, and the treasurer, secretary, and sergeant-at-arms (parliamentarian) to the outside, seated at desks next to the front table. The rest of the members also sit by rank, although this organization is unofficial and unstated. In this seat-ranking, older members tend to sit to the right side of the room (facing the front of the room), while younger members sit to the left. Very few members sit on the left-hand side of the room. An idealized seating arrangement in shown in figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Seating arrangement in meetings

The audience is also an important factor in the meeting. When a member speaks, he is not addressing one or two members, but all fraternity members. Even when two members speak directly to each other, all members are “ratified overhearers” (Goffman 1981), and thus are, in effect, the audience. Often, this audience will also evaluate members’ statements: very witty or apropos statements receive applause, sensitive and controversial statements are generally evaluated with silence, outrageous statements elicit general chaos, and funny remarks meet with laughter. A particularly skillful remark is met with a group chant, in which members circle their fists in the air and rhythmically chant a high-pitched whoop. There can be no doubt, then, that members are closely evaluated when they speak during meetings.

Even from these cursory descriptions, it is possible to discern that there are in fact some interesting similarities between the cultures’ gatherings. Table 5.1 provides a summary of the speaking grids for each of these events. Such a listing of the components is not a replacement for a more complete exposition of each event (see Sherzer 1987: chapter 3; Kiesling 1997, 1998, 2001); however, it does allow us to compare the events. When we do this comparison, we find similarities as well as many expected differences. The similarities are in some cases very general. For example, we find that both of these meetings take place regularly and facilitate the social cohesion of both groups. Both gatherings are in general serious, and have expected configurations in which participants are expected to sit. The norms of interaction provide a particularly interesting set of similarities and differences. In both cases one speaker speaks at a time, but even though at first both settings might seem to have one speaker dominating the event (the chief for the Kuna and the president or whoever has the floor at the time for the fraternity), there is interaction, or dialogism, built into both. The Kuna achieve this in two ways. First, one chief must respond to another; if there is only one chief present, he cannot chant. Second, the “spokesman” responds to the chanting by interpreting the chant, doing more than translating but in many ways responding to it. The fraternity in general allows anyone who wants to speak to do so, and thus members can respond to each other even though they are addressing the entire meeting. In addition, short comments and jokes are not only tolerated but encouraged, so that there is a kind of running commentary on how the meeting is going. These are just a few examples of the kinds of insights we find when we are forced to do this kind of descriptive comparison.

Table 5.1 SPEAKING grid for a whole-village evening gathering and a fraternity meeting

| Kuna | Fraternity | |

| Situation | Setting: evening. Round house with “chiefs” in center, then men, then women. Women work on molas.

Scene: work finished, supper eaten, relaxing, coming together | Setting: Sunday evening. Classroom with officers at front and younger men to the left.

Scene: reconnecting after a usually busy social weekend |

| Participants | “Chiefs” (minimum two), spokesmen, policemen, villagers | Full members of the fraternity (not pledges) |

| Ends/purpose | Ends: social connection and cohesion

Purpose: build status, settle dispute in favor, teach/learn about culture | Ends: conduct fraternity business (planning, decision-making); social cohesions and connection

Purpose: build status, get elected, have certain policies adopted |

| Act sequence | Pre-meeting talk: informal talk or public discussion of important issues

Form: the points of the chief’s chanting are indirect; reformulation/interpretation by “spokesman”; set sequence of acts Content: historical; mythical-cosmological-historical; local history; Kuna versions of the Bible; chief’s personal experience, dreams; stories (humorous) | Pre-meeting talk: chatting about social events over the weekend

Meeting: direct and often confrontational Content: set sequence of topics: reports, old business, new business; fraternity business such as planning social and philanthropic events; disciplining members |

| Key | Usually serious, but can be lightened | Serious but with lots of intermittent joking. Often adversarial and confrontational. |

| Instrumentalities | Channel: oral

Mode: chanting, speaking Forms of speech: chief language (chiefs), ordinary Kuna (spokesmen and others) | Channel: oral

Mode: speaking Forms of speech: American English, with varying levels of standardness |

| Norms | Interaction: two chiefs, one chanting, the other responding. Spokesperson speaks when chief is finished.

Interpretation: interpreted as lessons or entertainment (or both), fitting into the cosmology and social structure of Kuna | Interaction: one speaker at a time determined by the president or other presiding officer. Short unratified responses (comments, jokes) are OK. Challenges to previous speakers are OK.

Interpretation: interpreted as contributions to the fraternity, but some utterances can be seen as counter-productive. Many utterances in response to others will be seen as challenges to the first speaker, but are interpreted as part of the debate involved in democracy, and important ideology in the governing of the fraternity. |

| Genres | Meeting house | Meeting |

This descriptive work is also important because we can make other comparisons. For example, in norms of interaction, we could create a checklist of sorts that includes some of the linguistic features in Part III of this volume: silence, directness, and turn-taking, among others. These would all be listed in the Norms section. For the fraternity section, we would have to list a norm of interaction that a single speaker talks at a time and no one else speaks until he indicates he is finished, and the president chooses the next speaker. However, in norms of interpretation we can note that violations of this rule are not, for the most part, punished in any way, and in fact some are rewarded with laughter. Based on Sherzer’s description of the Kuna gathering house meetings, we would list a similar “one-at-a-time” turn-taking, but with much more serious consequences in norms of interpretation.

Viewed across speech events in a single culture, we might find that some speech events are similar and group themselves into genres. Thus the fraternity meeting will be similar to other group meeting speech events, such as sorority meetings and meetings of student organizations, while at the same time providing a way to describe differences (for example, sorority meetings involve singing and chanting, student organization meetings are much more focused on the business of the organization and less on the cohesion of that organization). So, while actual SPEAKING grid analyses have not appeared in the literature on intercultural discourse and communication, such grids can be an extremely useful heuristic and checklist for what aspects of a speech event and its community are salient for an analysis, whether the comparative study be across or within cultures.

NOTES

1 All names are fictitious.

2 Meetings held in “ritual” (held in secret, employing the secret symbols and liturgy of the fraternity) are somewhat more formal than the weekly meetings, in that there are parts of the meeting that are scripted. However, the main body of a ritual meeting functions as a weekly meeting. I was not permitted to record the secret portions of these meetings.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Austin, John L. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1933. Language. New York: Holt Reinhart Winston.

Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton.

Chomsky, Noam. 1964. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. The Hague: Mouton.

Eckert, Penelope and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 2003. Language and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goffman, Erving. 1981. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gumperz, John. 1968. The speech community. In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. New York: Macmillan. 381–6.

Gumperz, John and Dell Hymes. 1986. Directions in Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hymes, Dell. 1962. The ethnography of speaking. In Thomas Gladwin and William C. Sturtevant (eds.). Anthropology and Human Behavior. Washington, DC: Anthropological Society of Washington. 13–53.

Hymes, Dell (ed.). 1964. Language in Culture and Society. New York: Harper and Row.

Hymes, Dell. 1972. Models of the interaction of language and social life. In John Gumperz and Dell Hymes (eds.). Directions in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. 35–71.

Hymes, Dell. 1974. Foundations of Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Hymes, Dell. 1986. Models of the interaction of language and social life. In John Gumperz and Dell Hymes (eds.). Directions in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication. Malden, MA: Blackwell. 35–71.

Kiesling, Scott F. 1997. Power and the language of men. In Sally Johnson and Ulrike Meinhof (eds.). Language and Masculinity. Oxford: Blackwell. 65–85.

Kiesling, Scott F. 1998. Men’s identities and sociolinguistic variation: The case of fraternity men. Journal of Sociolinguistics 2(1), 69–100.

Kiesling, Scott F. 2001. “Now I gotta watch what I say”: Shifting constructions of gender and dominance in discourse. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 11(2), 250–73.

Kiesling, Scott F. 2002. Playing the straight man: Displaying and maintaining male heterosexuality in discourse. In Kathryn Campbell-Kibler, Robert J. Podesva, Sarah J. Roberts, and Andrew Wong (eds.). Language and Sexuality: Contesting Meaning in Theory and Practice. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. 249–66.

Labov, William. 1966. The Social Stratification of English in New York City. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Levinson, Stephen. 1979. Activity types and language. Linguistics 17, 365–99.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1963. Structural Anthropology. Trans. Claire Jacobson. London: Basic Books.

Patrick, Peter. 2004. The speech community. In Jack Chambers, Peter Trudgill, and Natalie Schilling-Estes (eds.). The Handbook of Language Variation and Change. Oxford: Blackwell. 573–97.

Searle, John. 1969. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sherzer, Joel. 1987. Kuna Ways of Speaking. Austin: University of Texas Press.