14

“Those Venezuelans are so easy-going!” National Stereotypes and Self-Representations in Discourse about the Other

1. Self- and Other-Representation

Talking about other people, or groups of other people, is an activity in which people not only engage frequently, but also invest a considerable amount of emotional energy. The emotional investment can be best be explained by the fact that this activity is not fundamentally about giving neutral and “objective” characterizations of the others but about accomplishing implicit aims while we ascribe properties to the others: we may wish, for instance, to corroborate our worldviews, and by doing so we may also hope to corroborate and reproduce, for ourselves and for our ingroups, the picture we have constructed of ourselves.

This contribution deals with outgroup and ingroup representation in dialogues and in discourse where the otherness referred to is about nationality and national-cultural differences. Self-and other-representation involves activating cognitive categories, which, if they are not satisfactorily “qualified” (and how could they be in an absolute sense?), will be likely to be understood by those who do not share our views as “stereotypes” or even “prejudice.” Even though the concept of stereotype is commonly taken to be fundamental in intercultural communication studies, it needs some “unpacking” before it can be meaningfully used. “Stereotyping” will here be regarded, not as the expression of simplistic or prejudiced views, but as an instance of a more comprehensive process, namely categorization, a phenomenon which could be considered in both a cognitive and a social perspective.

1.1 Categorization As a Cognitive Phenomenon

Let us start by taking a closer look at the cognitive aspects of categorization. Categorizing things and people can be seen as “creating theories” about objects that we observe (Lakoff 1987): once a category is established it will turn into a “box” which we fill with content by means of attributing properties to it. In fact, if we did not produce “theories” in this way, we would not be able to create any concepts that we could store in our memories, nor would we be able to continue perceiving the objects for any longer stretch of time, but would start overlooking them instead. Once, however, that we have created a category, we are not only unwilling to change or exchange it, but we also tend to continue perceiving precisely that category every time we are confronted with a phenomenon or property that we once related to it. This is what Harvey Sacks referred to as the “Observer’s paradox” (Sacks 1974: 225), one of the effects of which is “immunity to induction,” which is to say that we refrain from trying to create new categories from observations which are already tied to a category.

The categorization process can be described both from a purely cognitive-psychological viewpoint and also from social-psychological (ethnomethodology, see e.g. Garfinkel 1984) and linguistic perspectives (conversation analysis, see e.g. Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson 1974). So-called membership categorization analysis (Sacks 1974; Hester and Eglin 1997; Hutchby and Wooffit 1998) is a recent discipline which combines the latter two perspectives by addressing the issue of how categorizations come about and are expressed in and through interaction and, more particularly, how they are used for establishing identities in talk (e.g. Antaki and Widdicombe 1998). In an empirical study presented and commented on in sections 2 to 5, these and related methods will be applied.

Stereotypes, understood in a wide sense, can be regarded as “membership categorization devices” (Sacks 1974), or “messages,” by means of which properties or descriptive categories (e.g. “stingy”) are endowed with a positive or negative value (“negative” in the current case) and attributed to extensional categories (e.g. “the Dutch/Scottish/Catalans”). In case the extensional category corresponds to the ingroup, the stereotype is part of a “self-representation”; in the opposite case, we talk of “other-representation.”

As a consequence of general cognitive mechanisms, we cannot avoid stereotyping when thinking and talking of categories (cf. Gudykunst and Kim 1984), and as a consequence of the above-mentioned “Observer’s paradox” we have a strong tendency to stick to stereotypes once they are established. Stereotyping works in two directions: if a given property is ascribed to one member of an extensional category, it automatically extends to all members (generality); conversely, all members of a given category are taken to be alike with regard to a given property once the ascription has been established (homogeneity).

While offering an alternative socio-psychological perspective on stereotypes, labeling theory (see e.g. Hayes 1993) arrives at similar conclusions: the labeling of descriptive and extensional categories (i.e. properties and groups) are necessary for the creation of identities – both those ascribed to the outgroup and those established for the ingroup (Hayes 1993: 155–6). This establishment of self-and other-representations is further corroborated by the fact that it is associated with “common sense” (Gwyn 1996): consensus is soon established within the ingroup that the idea of “X-es being Y-ish” is a natural or even self-evident one.

Appraisal theory – a fairly recent subdiscipline in discourse and dialogue analysis (see e.g. Martin and White 2005) – has shown that the utterances we produce in discourse necessarily include an evaluative element. Three classes of appraisal or evaluation are defined: “affect,” “judgment,” and “appreciation.” In somewhat simplified terms, “affect” is to do with the speakers’ commitment to the topic of an utterance (“I’m so worried about her economy”), whereas “judgment” is related to the activation of some social norm (“she can be quite disruptive”) and appreciation is related to more general, e.g. aesthetic values (“she’s an excellent manager”). In the terminology of traditional semantics, all meaningful elements that are not classifiable as tokens of appraisal can be said to represent “denotative” or “referential” meaning. Denotative meaning is contrasted with so-called connotations, which can be said to represent all three types of appraisal. What has been referred to above, in the tentative definition of stereotypes as messages being endowed with a positive or a negative value, is a direct reflection of judgment and appreciation taken jointly, considering that all norms and ethic or aesthetic values are expressible in terms of the basic valuations “good” vs. “bad.”

It should be kept in mind that although appraisal is never quite absent in discourse (let alone in categorizing utterances), there is always a possibility of dissociating denotative meaning from connotations (= judgment and/or appreciation). This point becomes clear when we realize the existence of frequent positive/negative pairs of categorizations, such as “having a sense of economy” vs. “being stingy,” “showing interest in other people” vs. “being a gossip,” or “being frank” vs. “being blunt.” This possibility of inverting valuations provides a means of agreeing on denotative meanings while keeping separate evaluations of an object, an individual or a group of objects or people.

From what has been said hitherto with regard to stereotypes, categorization and self-vs. other-representation, it should be clear that we are dealing with socially shared discursive constructions. Such constructions have a tendency of agglutinating into what could be referred to as “cultural perspectives” (Ylänne-McEwen and Coupland 2000: 209). It is important to keep in mind that cultural perspectives are basically the same kind of phenomenon regardless of whether their holders are laymen or specialists. The main difference between lay and specialist (the latter including scientific) perceptions is to what extent the categorizations established are qualified and nuanced. The path towards complex representations naturally runs through more simple and less qualified perceptions.

1.2 Categorization As a Social Phenomenon

Given that categorizations are socially shared constructions, two aspects of self-and other-representation become particularly relevant: first, the ways in which categories are created and expressed in interaction and, second, what social effects they produce once they are expressed.

As regards the interactional aspect, it is important to keep in mind that there is no other way for categorizations to be created, produced and reproduced than in and through interaction. Spoken interaction could be regarded as fundamental in this sense, although interaction, in a wider sense, could also arise in writing: in speech as in writing there are senders, addressees, and wider audiences that receive the messages expressed.

Categorizations are far from always presented explicitly, through direct verbal means (“you Scottish people are so stingy”), but are often expressed indirectly or even in an entirely implicit manner. Saying, for instance, in the presence of a Scotsman (Dutchman, Catalan), that “we like to be generous and spend money on these things” could easily lead to the inference “in contrast to you,” from which a further inference would be “since you are Scottish (Dutch, Catalan).” An even more implicit means of expressing the stereotype of Scottish (Dutch, Catalan, etc.) people being stingy would be, for instance, to say – in the presence of the same Scotsman (Dutchman, Catalan) – that “I imagine you wouldn’t like to contribute any money to this.” The example may be thought of as childishly simple; yet the conversation analyst Dennis Day has described how, for instance, a native employee at a Swedish workplace, in the context of a multi-party talk about planning a party, was “ethnifying” his addressee, a colleague of Ethiopian origin, by referring to the supposedly Ethiopian – and from the speaker’s perspective disgusting – custom of melting lamb fat (Day 1998: 157).

The non-Swedish addressee, in this case, made an effort to resist “ethnification” by simply changing the subject. The incident, however, illustrates an important social effect of outgroup categorization in dialogue: although one may try to ignore what is being said, the fact that someone else actually categorizes you as part of a group makes your group identity relevant and obliges you to take some position with regard to the ascribed identity. At the same time, activating other-representations, as in the case of the aforementioned native Swedish speaker, has parallel effects on the sender’s group identity, since by doing so, a self-representation of being different from “those others” is invoked.

The relevance-making of opposed social identities triggers, in turn, a process of relating to otherness, either by simply reinforcing barriers to the opposite group, or by trying to overcome – at least symbolically – the differences perceived. Influential theories within social psychology have contributed to describing these mechanisms on a smaller or larger scale of group interaction. The most well-known disciplines arising from this concern are intergroup theory (see e.g. Tajfel and Turner 1986) and its “successor,” accommodation theory (see e.g. Giles and Coupland 1991: ch. 3).

The process of accommodating to, or distancing oneself from, the Other can also be regarded from a discourse perspective. Thus, social-psychological approaches have been fruitfully combined with linguistic analysis in studies on face (e.g. Goffman 1967), politeness (e.g. Brown and Levinson 1987) and rapport management (e.g. Spencer-Oatey 2000). The notion of face, i.e. the social projection of an individual’s or a group’s self-image, should be seen as intimately connected with the notion of individual and collective identity (cf. Fant 2007: 342–3).

Face-work is often related to individuals’ striving to project themselves as possessing “good” properties, as being assigned specific social roles, or as occupying positions on a hierarchy scale. These projections are means for establishing individual identity. However, group identity – defining oneself as a member of an extensional category with ascribed properties – always influences, and becomes part of, individual identity. In a communicative situation where a participant’s group membership is referred to by another participant by means of negative or positive categorization, it is very difficult for the first participant not be become affected, and the more evaluative the remark, comment, etc. is, the greater the impact will be. In case of a negative judgment or appreciation, the participant will perceive, to a greater or lesser extent, that her/his identity is under attack.

A final social effect of the discourse of self-and other-categorization deserves to be highlighted, namely that the resulting representations are, more often than not, transformed into motives for social action (Coupland 1999). Wars are based on the discursive construction of an Enemy, just as discrimination on all levels requires the discourse-mediated creation of an inferior Other (cf. e.g. Fairclough 2000). This is why stereotyping plays such an important part in intergroup relations and should be a central object of study in intercultural communication research.

2. An Empirical Study on Reciprocal Stereotyping

In a project carried out by Adriana Bolívar, Central University of Venezuela (UCV), and Annette Grindsted, University of Southern Denmark, together with the present author, the aim was to describe how representatives of two ethnic groups stereotyped each other reciprocally within a corporate setting. Results from this project have been accounted for in e.g. Bolívar and Grindsted (2005, 2006) and Fant (2001, in press), and will be addressed in the following sections of this chapter. The data collected in the project consisted of semi-structured interviews, i.e. encounters where the interviewer uses a script with questions to be ticked off without necessarily following a strict order, and where the respondents are encouraged to give as free and unimpeded accounts as possible while the interviewer takes the role of a committed listener (as regards techniques of semi-structured interviewing, see e.g. Suchman and Jordan 1992, or Houtkoop-Steenstra 1997). Apart from the interviewers, who were the researchers themselves, the participants were employees at mid-executive level, including a few chief executive secretaries, at different subsidiaries of Scandinavian-owned companies in Mexico and Venezuela. The two contrasted groups were Scandinavian (Swedish or Danish) staff and local Latin American (mainly Mexican and Venezuelan) staff, both sets having worked in the company for several years. The data comprises thirty-one interviews with a mean length of thirty-two minutes.

The format of most of the interview items can best be described as “tell-me-what-they-are-like” questions, mainly with regard to different aspects of professional life, although the responses had a tendency to extend far beyond the corporate domain. The questions varied from quite general issues (“What is it like to work with Danes/Swedes/Mexicans/Venezuelans?”) to more specific and concrete issues (“How do you think they go dressed at work?”) and other issues that were more interpretive in nature (“Do you think the Danes/Swedes/Mexicans/Venezuelans you’re working with behave politely or not so politely?”). The interviews had thus been arranged so as to yield as many categorizations as possible. Although most respondents made an effort to produce qualified judgments, the responses consist of what may be classified as “stereotypical representations” in a wide sense.

The project included a set of interrelated research questions. The opening question regarded which precise other-categorizations would come out most frequently in each group of respondents. A less self-evident question was to what extent self-categorizations would also appear in the data and, in that case, which would be their content. Questions pertaining to a higher level of sophistication were the following: (1) To what extent would the responses display contrastive and complementary patterns such that the categorizations (self-or other)ascribed to one group would be opposed to those ascribed to the other group? (2) To what extent would the responses made by one group converge with those made by the other group, with regard to both “denotative” and appraisal meaning? Finally, as a consequence of the answers to the two preceding questions, (3) could “collaborative” patterns between the two sets of responses be ascertained?

A sixth and final question concerned what effects the interaction would have on the participants in terms of face and identity work. With regard to this, it deserves underscoring that these data can be seen either in a monologic perspective, as “text,” or in a dialogic perspective, as “interaction” (Linell 1998: 277–8). The first five research questions basically addressed textual aspects of the data while only the sixth question addressed interactional aspects. Important corollary questions regarding the interaction that took place in the interviews could for instance have addressed what influence the interviewer’s attitudes and feedback moves would have on the respondents’ performance. Nonetheless, these and similar questions, however justified and relevant, would fall far beyond the scope of the study.

3. Complementary Categorization

What are the most frequent and most salient stereotypical ideas that circulate, on a worldwide basis, about Latin Americans, on the one hand, and about Scandinavians, on the other? In order to give a reliable and valid answer to that question, a survey covering a wide variety of nations or geographical regions would be needed, which is undoubtedly a difficult (although by no means impossible) scientific task. A fair guess, however, is that the outcome of a global survey of this kind would be difficult to assess, due to the simple fact that different people, and different national groups, will have views that vary a lot with regard both to clarity (will people have any distinct idea at all about e.g. Latin Americans?) and commitment (how value-laden will their ideas be?).

By limiting the survey population to people who actually have the experience of living or working with the national group under consideration, these factors can be kept more under control and result in more qualified (though, admittedly, less salient) judgments. In the aforementioned empirical study on Latin Americans’ and Scandinavians’ views of each other within a corporate setting, only two ethnic groups were contrasted and compared, and all participants were well acquainted with the “other” group.

The categorizations that were expressed in the data were clustered in “families” of similar content (e.g. being “structured,” having a “sense of organization” and being “good at planning” were put in the same cluster), and all categorizations, self-or other-, that appeared in more than one interview were listed. The ten most frequent categorization “families” turned out to be distributed in an entirely symmetrical way:

Table 14.1 Categorizations of Latin Americans and Scandinavians

| Categorizations of Latin Americans | Categorizations of Scandinavians |

| Bad organizers | Good organizers |

| Socially skilled and easy-going | Stiff and socially unsophisticated |

| Insufficient level of education | High level of education |

| Polite | Blunt or rude |

| Unfocused | Highly goal-oriented |

| Know how to enjoy life | Do not know how to enjoy life |

| Low respect of human rights | High respect of human rights |

| Considerate | Inconsiderate |

| Low efficiency | High efficiency |

| Elegant | Uncouth |

The fact that the stereotypical representations were so easily arranged in pairs may seem surprising, considering that the specific categorizations were by no means induced by the questions, and considering, too, that the opinions were given in a type of talk which rather resembled unstructured everyday conversation. On a closer look, however, this result is not so difficult to explain. The environment itself, with its mixture of Latin American and Scandinavian staff, in combination with the encompassing topic of the interview (“What are they like?”) strongly invited the making of comparisons. In fact, a majority of responses involved some sort of comparison, explicit or implicit, in spite of the fact that the respondents were never asked to compare.

An interesting conclusion to be drawn from the list is that there seem to be common traits in the discourse about “the Other” that takes place in these mixed workplaces, regardless of the size and activity of each company, and also regardless of their location – Mexico or Venezuela. A particularly salient trait is that Latin Americans are considered to be better off with regard to social relationships and life-style, whereas Scandinavians are regarded as superior with regard to task-related features. Both parties seems to agree on those characterizations, a phenomenon we will return to in section 4. Before doing so, however, let us take a look at the ways in which the stereotypical representations – in terms of both self-and other-categorizations – were asked in the interviews.

The interviewees were only asked to give other-characterizations. In spite of this, it frequently happened that opinions about their “own” national group followed directly upon their characterization of the other party. This can be clearly seen in the following excerpt from an interview with a Venezuelan respondent. (NB. In this and the following sequences, the utterances in the original language are reproduced according to common transcription conventions – see list at the end of the chapter –, whereas the English translation, put in italics, follows usual orthographic norms.)

(1) R[espondent]: Lucía (Venezuelan), the chief executive’s secretary. I[nterviewer]:

Ana (Venezuelan).

I: hay algo que te gusta mucho mucho de los daneses o que te desagrade de verdad en la forma de ser y de actuar de los daneses.

Is there anything you like very much about Danes, or that you really dislike in their ways of being and behaving?

R: (4.0) ay para mí ellos son muy chéveres todos o sea para mí todos-no no tengo aspectos negativos en sí: de ellos no-o sea lo más negativo es eso de esa impaciencia no,

Oh no, as far as I’m concerned they’re all just fine. That is, as far as I’m concerned, everybody…I don’t have any negative opinions…properly speaking…about them, right…That is, the most negative thing is that of…that impatience, right?

I: mm:

R: que de repente nosotros queremos llevar la vida como más despacio y ellos quieren ir muy rápido y y y no me disgusta no, porque pienso que tienen razón no, nosotros no podemos estar toda la vida con esa lentitud no,

Because we sometimes want to take things sort of easier and they want to go ahead so fast and…and I’m not against it, because I think they’re right, aren’t they? We can’t go on the whole life being this slow, can we?

I: somos muy lentos sí eso es cierto. ((GIGGLES))

We’re very slow, yes, that’s true.

R: no podemos. y entonces ellos quieren ver resultados inmediatos y y nosotros no no nos importa mucho los resultados inmediatos

No we can’t. And then they expect to see immediate results and…and we aren’t that keen on immediate results.

In this sequence, the Venezuelan respondent expresses her views in an altogether explicit manner. After a negative characterization of Danes as being “impatient,” she makes a direct comparison, which is seemingly neutral: “they” are fast while “we” take it easy. She then goes on explaining her point: wanting things to go “fast” is not such a bad thing, although Venezuelan slowness is; hence, “they” are right and “we” are wrong. After the interviewer has given positive feedback on that view (the “we” of solidarity should be taken notice of), the respondent makes a second direct, albeit less value-laden, comparison: “they” expect to see immediate results whereas “we” do not.

Categorizations were far from always expressed in this direct manner, especially not when they were negative. In the following excerpt from an interview in Danish with a mid-level executive of Danish origin, the respondent starts beating about the bush while expressing her view on Venezuelans:

(2) R: Catrine (Dane), mid-executive. I: Asta (Dane).

I: hva syns du om deres sociale kompetence.

What do you think of their social skills?

R: glimrende. ((LAUGHS)) den er helt fin. ja øh: altså øh-der der vil jeg så nok tro at øh-de er lisom gode ti å få få hvert øjeblik udnyttet hvakamansi maksimalt når man tænker på det sociale ik. … altså det er de fine til lisom at gribe nuet å så få: få et eller andet sjov ud af det hele hvor vi andre danskere sådan er mere-nu hvor vi altså er i møde så ka vi ikke snakke om fodboldkampen igår og sådan noet nu koncentrerer vi os ik,

Excellent. Fine indeed. Well, uh…actually, uh…about that, I would also say that…uh…they’re sort of good at taking advantage of each moment…how should I put it…in full, as far as social things are concerned, right. … I mean, they’re good at sort of living in the present and then get some fun out of it, whereas we Danish people, we’re sort of more like “now that we’re in a meeting we can’t talk about yesterday’s football game and things like that, now we should concentrate on the issue, shouldn’t we?”

So far, this would look like a predominantly positive opinion: Venezuelans are socially skilled and easy-going, in contrast to boring and over-zealous Danes. Already the frequently occurring hedges, such as “uh,” “how should I put it,” or “sort of,” may lead us to suspect that there are hidden valuations to the effect that Venezuelan easy-goingness is not altogether that good, and Danish stiffness not such a bad thing after all. These appreciations become entirely clear in the respondent’s following turn:

(2, continued)

R: hvor de andre de de formår ifølge dem selv at kombinere begge dele ik,

Whereas the others, they succeed, according to themselves, in combining both things, right?

I: så resultatorienteringen,

So what about their goal-orientation?

R: jeg vil sige resultatorienteringen kan glippe.

I would say their goal-orientation can fail.

By adding the phrase “according to themselves,” the respondent shows that her earlier statements do not represent her own opinion, but are a report of what she takes to be a Venezuelan people’s general self-image. The interviewer, who has got the hint, suggests an explicit reformulation of what she assumes the respondent to have expressed indirectly, and her suggestion is immediately confirmed, and expanded on, by the respondent.

In this excerpt we have seen an example of how a set of other-representations may be expressed indirectly, in the sense that the denotative content of the utterance is explicit while the negative evaluative content is hidden: “Venezuelans are easy-going, though at the expense of reliability and goal-orientation, which is bad.” It is also an example of an implicit positive self-representation: “they are not as goal-oriented as we are, we are goal-oriented people, and that is good.” The reasons for not expressing explicitly a positive self-representation in this context are obvious: first, ingroup characteristics are not the topic of the talk and, second, being over-enthusiastic about one’s ingroup would entail a risk of seeming either naïve or chauvinistic, especially in a mixed-ethnic corporate environment such as in the current case.

In contrast to what was shown in sequence (1) above, where the Venezuelan female interviewee gave an explicitly negative opinion about her own national group, unfavorable self-representations more often came out in indirect or implicit ways. A strategy for expressing a negative view of one’s ingroups in an implicit manner can be seen in the following sequence, where a Mexican mid-executive is interviewed – not by a compatriot, as in sequences (1) and (2), but by a representative of the nation (Sweden) where the company’s headquarters are situated.

(3) R: Lorenzo (Mexican), mid-level executive. I: Leif (Swede).

I: entonces la primera pregunta es e:: qué opinas en términos generales de los suecos

Then the first question is, uh…what is your opinion generally speaking about Swedes?

R: ajá, ((SIGHS)) bueno pues e: en general me parece que: (2.0) que trabajar con los suecos e significa trabaja:r pues en una forma ordenada sistemática e:: y que tiene pues e: muchas ventajas porque e:: m: pues evidentemente es mucho más fácil ponerse de acuerdo cuando llevas una secuencia lógica de las cosas-

Oh, well then, uh, generally speaking I think that…that working with Swedes, uh…means working…well, in an orderly systematic way, uh…and that it has many advantages because, uh…mm…because obviously it’s much easier to come to an agreement when you have a logical sequence of things…

It is not unlikely that the presence, in a Swedish-owned company, of an interviewer who is not only foreign but Swedish leads the respondent to make more polite and positive evaluations about Swedes than he would have done otherwise. More important than what he says about Swedes, however, is what he appears to be saying about his ingroup. Although he makes no explicit mention of Mexican people, and chooses to talk in entirely impersonal terms, there is no doubt that he is making an implicit comparison between the two national groups. So, if the Swedes are “orderly” and “systematic” and structure things in a “logical” way, the inference can be drawn than he considers his ingroup to be worse off in all these regards. The frequency of hesitation markers can be interpreted as the sign of a combined effort to formulate himself politely about Swedes, on the one hand, and to avoid making any explicit reference to shortcomings on the part of his compatriots, on the other. In fact, this and similar strategies for avoiding direct and explicit negative self-categorizations occur much more frequently in the data than explicit judgments of the kind we saw in sequence (1).

In summary, the respondents, who were asked to give their opinion of the “other” party, more often than not ended up making comparisons between the parties. This happened so consistently across the data that the categorizations could, as we have seen, be listed, practically without exception, in contrastive pairs. On the other hand, in cases where the self-categorizations were negatively laden, the respondents mostly preferred to express them indirectly or implicitly, presumably as a face-saving strategy. Similar face-saving strategies occasionally applied to their other-categorizations, too – sometimes as a preparatory move (as seen in sequence (2)) before giving a more “sincere” opinion. Finally, it should be kept in mind that self-categorizations occur less frequently in the data than other-categorizations, and are expressed in less salient ways. An obvious reason for that is the topic of the interview itself. There may, however, be other reasons for inhibiting self-categorization, as will be briefly discussed in section 5.

4. Reciprocal Stereotyping

We have been able to see, so far, that the other-representations that were expressed by each party hardly ever coincided; on the contrary, the categorizations could, to a very high degree, be arranged in a complementary pattern of contrastive pairs. We have also found that the other-categorizations produced were often followed up by an expression of self-categorization. The question to be raised in consequence of this observation was to what extent the other-categorizations made by one party coincided with the self-categorizations made by the other party.

This convergence effect can be found when comparing sequence (3) above, where the Mexican respondent Lorenzo categorized Swedes as “orderly,” “systematic,” and “logical” and implied that Mexicans were not, with the following sequence, in which the Danish respondent was asked what first came into her mind when thinking of Venezuelans.

(4) R: Charlotte (Dane). I: Asta (Dane).

I: hva er dit første indtryk når du tænker på samarbejdet med venezuelanerne.

What’s your first impression when you think of working with Venezuelans?

R: ustruktureret.

Unstructured.

I: ustruktureret? det er det første der kommer ind i dit hoved

Unstructured? Is that the first thing that comes into your mind?

R: ja. det næste det er nok noget med gode intentioner mange planer forsøg på at være være struktureret men men det det er svært altså. devilsi der er forsøg på å være langsigtet. men man er altid meget tænker på nuet. man skal finde en løsning på det problem vi har her og nu. og man tænker ikke så meget på hvad der sker bagefter og hvilke konsekvenser det har.

Yes. The next thing would be something about good intentions, many plans, attempts to be structured. But…but it’s difficult, you know. I mean, people try to do long-term planning but they’re always very much…they’re focusing on the present. There should be a solution to the problem we’re having here and now, and not much thought is given to what will happen later and what the consequences will be.

Here, the respondent gives an extensive account of her opinion that Venezuelans are poor at organizing and planning, which can also be understood as implying that Danes are better in these respects. This is the mirror image of what Lorenzo expressed about Mexicans and Swedes in sequence (3). In both cases, Scandinavian “efficiency” was contrasted with Latin American “lack of structure.” Quite regardless of what realities may be underlying, or may have originally given rise to, these views, the convergence of stereotypical representations is an undeniable fact. Furthermore, it should be seen as clearly related to the aforementioned tendency to systematically compare the outgroup with the ingroup without being invited to.

Since this effect occurs so frequently in the data, it becomes reasonable to assume that the interviewees share their stereotypical ideas about both ethnic groups regardless of their own national belonging. In fact, they engage into something which could be called “collaborative stereotyping.” If we disregard the valuations attached to the denotative content of the categorizations, this tendency stands out as even stronger.

For what often happens is that the denotative content of a given self-or other-representation remains more or less identical, while the positive valuation of the representation is turned into negative, or vice versa. This may happen within the same interview, and the contrastive valuations may even occur in direct succession. The following sequence could illustrate this type of switch.

(5) R: Raúl (Venezuelan of Cuban origin), mid-executive. I: Ana (Venezuelan).

R: me gusta mucho la capacidad que tienen ellos de comercializar o sea lo agresivos que son y los ee ellos son muy ee aa emprendedores toman el riesgo en aa en comercializar. hay que ver que ellos son cinco millones de habitantes en un país pequeño entonces me parece que por ese lado son unos triunfadores y bueno los admiro por eso. o sea es por por eso precisamente es por a:

I quite like the marketing abilities they have, I mean, how aggressive they are and the…they’re, uh, very enterprising, they take risks in…marketing. One has to admit that they’re only five million inhabitants in a small country, so in that sense I think they’re winners and, well, I admire them for that. I mean, it’s precisely for that reason, it’s for, uh…

I: sí y qué es lo que te desagrada de verdad.

Yes, and what is it that you really dislike?

R: me desagrada es que el factor humano ellos no lo toman en cuenta. yo creo que ellos siempre subrayan la la parte técnica de exportar esto o: que cuáles son las características técnicas del equipo de esto pero ellos no toman en cuenta qué va a pensar fulano cuando hagamos esto, ellos el factor humano no lo toman para nada en cuenta.

What I dislike is that they don’t take the human factor into account. I think they always exaggerate the technical bit of exporting this, or what are the technical characteristics of this equipment, but they don’t take into account what other people will think when we’re doing this. They don’t take the human factor into account at all.

In the respondent’s first turn, Danes are praised for their professional efficiency in the domain for which the respondent himself is responsible in his company, namely marketing, as well as in general terms: they are “winners.” When explicitly asked to tell about his dislikes, he depicts the same efficiency as a negative trait for the reason that it entails inconsiderateness. Without having changed his view of Danes as efficient people, he has converted the positive sign of his earlier categorization into a negative sign. This move can also be seen in the perspective of identity defense, an issue to be addressed in the following section.

The “collaborative stereotyping” effect may not only mean that categorizations are shared between groups, regardless of whether self-or other-representations are involved. It could also imply the existence of a shared value scale, according to which certain positive qualities are more highly valued than other positive qualities, and, conversely, that given negative ascriptions are “worse” than others. There are a number of indications in the data to this effect. As a brief illustration, some of the statements made by the Venezuelan interviewee Lucía in sequence (1) may be quoted:

(6) = Sequence (1) partly repeated. R: Lucía, the chief executive’s secretary.

R: … the most negative thing is that of…that impatience, right? Because we sometimes want to take things sort of easier and they want to go ahead so fast and…and I’m not against it, because I think they’re right, aren’t they? We can’t go on the whole life being this slow, can we? … And then they expect to see immediate results and…and we aren’t that eager about immediate results.

What the respondent is saying is, in summary, that (1) Danes are impatient, which is a negative trait, (2) Venezuelans are easy-going, which is positive, (3) being impatient means wanting immediate results, which is positive, being a manifestation of the positive quality “efficiency,” (4) Venezuelans don’t care about immediate results, which is negative, and (5) Venezuelans are slow, which is more negative than anything else. There is no doubt that the positive-valued property “efficiency” ranks higher, in the respondent’s view, than the equally positive-valued property “easy-goingness,” and that the negative-valued property “slowness” is considered to be worse than the equally negative-valued property “impatience.” A quick look through the data will confirm that, in this way, the ranking of ascriptions systematically favors the Scandinavians and disfavors the Latin Americans.

5. Identity Defense

Following the line of reasoning presented in the previous section, it can be assumed that there exists, among the mixed staff of the companies where the interviews took place, a shared value-scale which tends to disfavor the Latin American party. We also know that people in general strongly tend to resist categorizations that would negatively affect their personal or collective face (cf. e.g. Antaki 1998; Day 1998; Fairclough 2000; Fant 2007). A natural question to be raised is then: how do the respondents – and in particular, the Latin American employees – go about in order to diminish this face-damaging effect?

First of all, compensatory strategies of various kinds should be mentioned. A positive other-categorization which implicitly entails a corresponding negative self-representation may be compensated by a (related or unrelated) negative other-categorization. We can see this happening in the following excerpt from the interview with the Mexican mid-executive Lorenzo. The excerpt follows shortly after the passage presented in sequence (3) above.

(7) R: Lorenzo (Mexican), mid-level executive. I: Leif (Swede).

I: pero: e: dime también lo negativo.

But, uh, tell me also about the negative things.

R: pues mira lo negativo tal vez que que tienen es que algunos verdad, e: toman esta e: actitud de neocolonialistas e: para ser más explícito de de que por el hecho de de: venir de un país e: e: más desarrollado con un nivel educativo mayor, con e: con e: pues e: mayor e: con un nivel de de de respeto a los derechos humanos mayor etcétera entonces este toman una actitud de perdonavidas no,

Well, look, the negative things about them, maybe, is that some of them, right, uh…take on that, uh…neocolonialist attitude, uh…, to be more explicit, that since they come from, uh…a more, uh…developed country with higher standards of education, with, uh…, well, uh…with a higher level of…respect for human rights and so on, then, uh…they take on an arrogant attitude, right.

Although the question was about negative traits, the respondent seems to be keeping in mind all the positive things he previously uttered about Swedes. The result is a rather drastic contrast between positively and negatively valued other-categorizations: Swedes, albeit “highly educated” and with a “great respect for human rights,” are depicted as “arrogant neocolonialists.”

A less confrontational strategy is to compensate positive other-representations that could be felt as a potential threat to one’s own collective face by giving expression to a counter-balancing positive self-representation. This strategy can be found to operate in a sequence such as (2), where the Danish mid-executive Catrine gradually switches from categorizing Venezuelans positively as “socially skilled” (and thereby implying that Danes are not) to expressing increasingly explicit positive views on Danes as “goal-oriented.” She ends up, however, combining this with the aforementioned strategy, when she explicitly ascribes a negative trait to the other party (“lack of goal-orientation”).

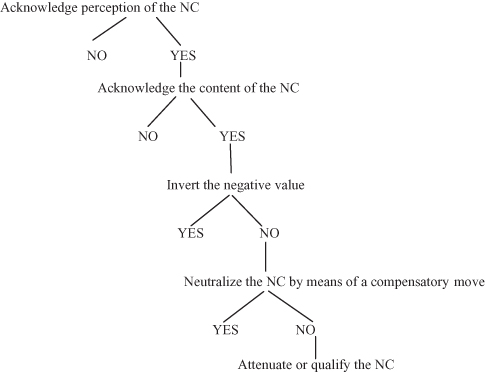

Inversion of valuations is another type of strategy, which may – but need not – occur in combination with compensatory moves. It consists in maintaining the basic denotative content of a categorization while changing its value. Thus, the negative value attributed to a given self-representation is turned into a positive, and, conversely, a positive value attributed to a given other-representation which is perceived as threatening to the speaker’s collective face is converted into a negative value. We have seen both mechanisms apply in sequence (5), where Danish “efficiency” and Venezuelan “inefficiency” are each given alternative interpretations with regard to valuation.

In more abstract terms, a pre-established set of strategies for resisting negative categorizations (NC) of one’s own group could be suggested. This set could be represented in a flowchart, as in Figure 14.1.

Figure 14.1 Resistance strategies against negative categorizations

Avoidance is an alternative type of strategy for resisting categorization and may, in principle, involve both other-and self-representations. Since other-representation constitutes the very topic of the interviews, it would hardly have been imaginable, in the current context, for the respondents to try to avoid categorizing the “other” party. Avoidance of self-representations, on the other hand, occasionally took place. This is a strategy which should be kept apart from that of down-toning negative self-representations by expressing them in an implicit or indirect way, of which we have already seen a number of examples. Self-representation avoidance is implemented by more subtle means, namely by suppressing cues that would lead the hearer to regard the speaker’s national group as a possible object of categorization. An example of this strategy can be found in the following excerpt from an interview with a Swedish mid-executive in a Swedish-owned company in Mexico:

(8) R: Leif (Swede), mid-executive. I: Leif (Swede).

R: JAG kommer väldigt bra överens vill jag påstå med dom allra flesta mexikaner … vad JAG har försökt göra e att försöka få dom att äh-dom som jobbar under MEJ åtminstone att äh-våga ta risker våga ta beslut. flera av dom som jobbar under mej har utvecklats på ett väldigt positivt sätt de här åren. dom vet att dom inte får stryk eller så vilket e vanligt i den mexikanska rena mexikanska hierarkin. att de e CHEfen som bestämmer. å han slår ganska hårt neråt på sina medarbetare om DOM-gör misstag.// DE gör inte JAG.

I’m getting very well along, I’d say, with practically all Mexicans. … What I have tried to do is trying to, uh…with those who work under my direction, at least uh…to make them dare to take risks, dare to make decisions. Many people who work under my direction have developed quite positively these years. They know they won’t get a beating or anything, which is common in a Mexican, purely Mexican hierarchy. That the boss decides. And he can peck quite hard, downwards, on his collaborators, if they do mistakes. I never do that.

As a result of the series of direct or indirect negative other-representations that the respondent expresses (“Mexicans are authoritarian, hierarchical, passive, cruel…”) the idea could occur to the reading audience that the speaker is implicitly referring to the opposite properties (“egalitarian, democratic, charitable…”), to be understood as typically “Swedish.” However, the respondent neutralizes this effect by referring emphatically to himself while consistently adding a contrastive accent to the pronouns “I” and “me” (indicated by upper-case letters in the Swedish transcription). Most probably, he is not doing this with any intention of saving the Mexican party’s face by inhibiting over-positive self-representations, but rather in order to preclude any associations with Swedes as a group. The contrast thereby created by the respondent is between him as an individual and Mexicans as a group, a move which both ascribes all the positive qualities to him and makes him immune to group categorization.

6. “So What Else Is New?” Concluding Remarks

Returning to the question of whether such self-and other-representations as have been encountered in this chapter should be considered “stereotypical,” in the sense that they could represent oversimplified, unjustifiably value-laden, incomplete or insufficiently grounded knowledge, it may seem superfluous to say that categorizations of this kind have not been submitted to any scientific test, nor could they be, in the shape they are expressed. Although some of these ideas may seem, in the eyes of many, to be “common sense” appreciations, it should be remembered that they all have a history, and that they have been reproduced, with or without modifications, across generations and/or from one category of people to another. They are discursive constructions and should be regarded as such until the contrary is proven, which is, of course, hardly likely ever to happen.

It was suggested in section 4 that the Latin American and Scandinavian staff who participated in the interviews shared not only a set of categorizations regarding both national groups, but also a value scale according to which properties typically ascribed to Scandinavians rank higher than those typically ascribed to Latin Americans. By way of induction, the hypothesis could be proposed that this asymmetric relationship is present also on a general plane, in the perceptions that Scandinavians and Latin Americans have of each other in general, and on an even larger scale, in the perceptions Europeans and North Americans have of Latin Americans, and vice versa (cf. de Cillia, Reisigl, and Wodak 1999).

A justified objection to such a claim would be the observation that the interviews took place in companies owned by Scandinavians and that the attitudes that were found only reflected the basic power relationship that would characterize those workplaces. On the other hand, it may then be questioned whether that power relationship simply is analogous to, or reflects, a global power relationship between economically and politically stronger and weaker nations or regions, within an order that has been labeled “The Empire” (Hardt and Negri 2000). “So what else is new?” could be the plausible comment on this question. This is a commonplace view, strongly represented in the media worldwide, maybe a stereotypical idea, but yet supported by countless findings from a wide array of scientific disciplines.

It is, today, a commonly shared insight that all power generates resistance (cf. e.g. Foucault 1980). Scholars of social sciences and humanities should be careful about keeping a mental distance from power hierarchies, local or global, in order to avoid becoming instruments of power. Facing the various and often subtle mechanisms of what Fairclough (1992) refers to as “minorization” – the discursive creation of “minorities” (this term being taken in a wide sense) of lesser value –, it is essential not to embrace stereotypical representations of groups of people in order to fight prejudice and discrimination.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

| Sign: | Meaning: |

| ((LAUGHS)) | non-verbal event |

| / | silence, ∼0.5 second |

| // | silence, ∼1.0 second. |

| /// | silence, 1–2 seconds. |

| (3.0) | extended silence measured in seconds. |

| : | prolonged syllable |

| . | falling endtone |

| , | rising endtone |

| - | self-interruption |

| “xxx” | reported speech |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Antaki, Charles. 1998. Identity ascriptions in their time and place: “Fagin” and “The terminally dim.” In Charles Antaki and Sue Widdicombe (eds.). Identities in Talk. London: Sage. 71–86.

Antaki, Charles and Sue Widdicombe (eds.). 1998. Identities in Talk. London: Sage.

Bolívar, Adriana and Annette Grindsted. 2005. La cognición en (inter)acción. La negociación de creencias estereotipadas en el discurso intercultural. Núcleo 22, 63–85.

Bolívar, Adriana and Annette Grindsted. 2006. Cognition in (inter)action: The negotiation of stereotypic beliefs in intercultural discourse. Merino 31. Institute of Language and Communication, University of Southern Denmark.

Brown, Penelope and Stephen C. Levinson. 1987. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coupland, Nikolas. 1999. “Other” representation. In Jef Verschueren, Jan-Ola Ostman, Jan Blommaert, and Chris Bulcaen (eds.). Handbook of Pragmatics 1999. Electronic publication (2007). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Day, Dennis. 1998. Being ascribed, and resisting, membership of an ethnic group. In Charles Antaki and Sue Widdicombe (eds.). Identities in Talk. London: Sage. 151–70.

De Cillia, Rudolf, Martin Reisigl, and Ruth Wodak. 1999. The discursive construction of national identities. Discourse and Society 10(2), 149–73.

Fairclough, Norman. 1992. Critical Language Awareness. London: Longman.

Fairclough, Norman. 2000. Discourse, social theory and social research: The discourse of welfare reform. Journal of Sociolinguistics 4(2), 163–95.

Fant, Lars. 2001. Managing social distance in semi-structured interviews. In Erzsébet Németh (ed.). Pragmatics in 2000: Selected Papers from the 7th International Pragmatics Conference, vol. 2. Antwerp: International Pragmatics Association. 190–206.

Fant, Lars. 2007. Rapport and identity management in Spanish spontaneous dialogue. In María Elena Placencia and Carmen García-Fernández (eds.). Research on Politeness in the Spanish-Speaking World. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. 329–58.

Fant, Lars. 2009. “Son como buenos para vivir el presente y lograr sacarle algún placer”. Estereotipación colaborativa entre latinoamericanos y escandinavos. In Martha Shiro, Paola Bentivoglio, and Frances Ehrlich (eds.). Haciendo discurso: homenaje a Adriana Bolívar. Caracas: Comisión de Estudios de Postgrado de la Facultad de Humanidades y Educación, Universidad Central de Venezuela. 545–68.

Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings. Ed. Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon.

Garfinkel, Harold. 1984. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Malden, MA: Polity Press/Blackwell.

Giles, Howard and Nikolas Coupland. 1991. Language: Contexts and Consequences. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Goffman, Erving. 1967. On face-work: An analysis of ritual elements in social interaction. In Erving Goffman. Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior. New York: Doubleday Anchor. 5–45.

Gudykunst, William B. and Young Y. Kim. 1984. Communicating with Strangers: An Approach to Intercultural Communication. New York: Random House.

Gwyn, Richard. 1996. The voicing of illness. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Cardiff University.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire. Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

Hayes, Nicky. 1993. Principles of Social Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hester, Stephen and Peter Eglin. 1997. Membership categorization analysis: An introduction. In Stephen Hester and Peter Eglin (eds.). Culture in Action: Studies in Membership Categorization Analysis. Washington, DC: International Institute for Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis/University Press of America.

Houtkoop-Steenstra, Hanneke. 1997. Being friendly in survey interviews. Journal of Pragmatics 28, 591–623.

Hutchby, Ian and Robin Wooffit. 1998. Conversation Analysis: Principles, Practices and Applications. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Linell, Per. 1998. Approaching Dialogue: Talk, Interaction and Contexts in Dialogical Perspectives. Amsterdam and Philadephia: John Benjamins.

Martin, James R. and Peter R. R. White. 2005. The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sacks, Harvey. 1974. On the analyzability of stories by children. In Roy Turner (ed.). Ethnomethodology: Selected Readings. Harmondsworth: Penguin. 216–32.

Sacks, Harvey. 1995. Lectures on Conversation. Ed. Gail Jefferson. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sacks, Harvey, Emmanuel Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. A simplest systematic for the organization of turn-taking in conversation. Language 50: 696–735.

Spencer-Oatey, Helen. 2000. Rapport management: A framework for analysis. In Helen Spencer-Oatey (ed.). Culturally Speaking: Managing Rapport through Talk across Cultures. London and New York: Continuum. 11–46.

Suchman, Lucy and Brigitte Jordan. 1992. Validity and the collaborative construction of meaning in face-to-face surveys. In Judith M. Tanur (ed.). Questions about Questions: Inquiries into the Cognitive Bases of Surveys. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. 241–67.

Tajfel, Henri and John C. Turner. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Stephen Worcher and William G. Austin (eds.). Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. 7–24.

Ylänne-McEwen, Virpi and Nikolas Coupland. 2000. Accommodation theory: A conceptual resource for intercultural sociolinguistics. In Helen Spencer-Oatey (ed.). Culturally Speaking: Managing Rapport through Talk across Cultures. London and New York: Continuum. 191–214.