The Changing Business Landscape

Tina McCorkindale, Aedhmar Hynes, and Raymond Kotcher

We are undergoing a revolution in human communication.

In less time than it took read that sentence—a single second—people around the world sent 2.5 million e-mails and 193,000 text messages, added 219,000 posts to Facebook and 729 to Instagram, viewed 125,833 YouTube videos, and tweeted 7,259 messages (internetlivestats.com 2016; Coats 2016; webpagefx.com 2016).

Every day, 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are created—so much that 90 percent of the data in the world today has been created in the last two years alone, according to analysts’ estimates (IBM 2016c). Much of this data is generated by individuals and captured by machines. The ability to access and understand this data from the “Internet of Things” is becoming a competitive differentiator for businesses. Think of all the data that enterprises1 collect about their customers—the difference between those who make sense of these data through analytics to improve the customer experience and those who will not be a primary determinate of those who succeed in business and those who fail in the years to come.

However, this is about more than just data and how we communicate.2 It is not just a revolution in human communication, but also one in the human experience.

The world’s balance of power is being transformed. There is a shift in the structure of the world’s demography. Millions are on the move from the Middle East to Europe, and across Eurasia and the African continent. Access to resources is becoming challenging, including fundamental human needs and rights, such as clean water, health care, nutrition, education, and equality. People are seeking and demanding transparency, integrity, and higher purpose from institutions everywhere.

Amidst this all-encompassing change, taking place at the speed of light, how does an enterprise succeed? For what changes in the business landscape do leaders need to be prepared?

In their CEO Report, Said Business School at Oxford University and Heidrick & Struggles (2015) reported chief executive officers (CEOs) are dealing with a business environment marked with uncertainty and change. CEOs said they value “ripple intelligence,” early warning systems much like the ripples on a pond, which sharpen as they learn to embrace the power of doubt. CEOs reported believing in an authentic sense of purpose for their organizations, and alignment in order to achieve it. Given intense stakeholder3 scrutiny, CEOs are looking for new ways to communicate effectively as old models become outdated; there are more audiences, languages, and communication channels than ever before.

In 2015, KPMG International published its Global CEO Outlook that surveyed more than 1,200 CEOs on the global economic challenges for the next three years, as well as their thinking on strategies for responding to those challenges. Growth is a top priority, even as CEOs navigate the vicissitudes of inconsistent regulations from country to country. Competitive threats not only from traditional incumbents, but also from new entrants, business models, and disruptive technologies represent increasingly challenging threats. Being relevant to customers, and maintaining both employee and customer loyalty, is critically important. In this digital age, cybersecurity and protecting private information are critical.

Similarly, PwC’s 19th Global CEO Survey (2016) of 1,400 CEOs reports that stakeholders have greater expectations operating in society with transparency and trust at the core. The CEOs reported a need for consistent and dependable communication, as well as the need to apply data and analytics to more effectively measure and express performance around business and strategy, purpose, and values. Nearly half said they are rethinking how they communicate “brand.”

Today’s business environment is going through changes on a level not seen since the Industrial Revolution. From technological to societal change, this upheaval presents CEOs and their Chief Communication Officers (CCOs) with numerous challenges: start-ups reinventing traditional business models, new ways of working, changing ways people interact with enterprises, and an increasingly diverse workforce. But where there are challenges, there are always opportunities. The question leaders need to ask themselves is, “Do I want my business to be a disruptor or disrupted?” Organizations that succeed will be those that thrive and adapt to this new environment, and CEOs need to be aware of multiple factors that will transform the landscape.

Business Landscape

Transparency, the primacy of the stakeholder, and engagement with purpose are all critical forces driving business and communication in this day of unremitting change.

Transparency

This is the age of transparency, or what The Economist (2014) calls the “openness revolution.” Stakeholders are demanding greater accountability and an end to “corporate secrecy” (p. 2) multinationals are being “forced” to reveal more information about themselves. According to The Economist, three forces are driving this: (1) governments demanding greater accountability; (2) the power of investigative journalism; and (3) the sophistication of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

In the Starbucks shareholder meeting in 2014, then CEO Howard Schultz emphasized how the world needs leadership more than ever, and companies have a responsibility to use the power of their businesses to do good in the world. He said, “The currency of leadership is trust and transparency” (p. 8). With such exogenous forces impacting the enterprise, transparency can no longer be borne out of practical necessity. It must be a deeply held value. Opacity comes with costs.

A survey by EY and the Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship (2013) of senior corporate professionals who were familiar with their organization’s sustainability efforts found that transparency with stakeholders was a key motivation for enterprises to disclose information, and most respondents reported business benefits as a result of their company reporting efforts. According to Iwata and O’Neill (2016, p. 4), “highly engaged stakeholders, empowered by social media and demanding of greater transparency, pose new challenges for protecting brand and reputation.” As reported in the Arthur W. Page monograph, The Authentic Enterprise (2007), power continues to shift to the stakeholder, and the demand for transparency will continue to grow.

The Primacy of Stakeholders

In 2006, then IBM Chairman and CEO Sam Palmisano said, “What is different now is that the concept of shareholders has expanded to stakeholders” (Blowfield and Googins 2006, p. 2). Thanks to social media and technological innovations, the stakeholder universe has expanded to a much wider set of individuals—both internal and external—that the enterprise must consider (Gitman and Enright 2015). Gitman and Enright, after a discussion with 16 member companies of Business for Social Responsibility (BSR), a global nonprofit organization, concluded, “In our increasingly transparent world, where a tweet can be as influential as an opinion in the board room, a company’s strategy to engage with and learn from its stakeholders has never been more important, or complex” (Gitman and Enright 2015, p. 2).

The Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship (2009) launched a report concluding a key competency of corporate leaders must be understanding stakeholders and their interests. According to the findings, “Nowadays, companies depend on favorable public opinion to ensure their license to enter, operate, and grow in markets around the world. This extends their agenda beyond compliance and following the law to understanding and engaging stakeholders and ‘balancing’ their interests in strategic decisions and operational practices” (p. 6).

The report also identified three reasons why the enterprise must be aware of the stakeholder landscapes where they do business:

1. Diverse stakeholders help shape the competitive context for business in a nation and globally;

2. They influence a firm’s license to enter, grow and operate in local global markets; and therefore;

3. Understanding and monitoring the stakeholder landscape is essential to the long-term planning of an enterprise. (Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship 2009, p. 5)

In one sense, this is not entirely new. After all, Arthur W. Page, who was vice president of public relations at AT&T from 1927 to 1946, said, “All business in a democratic society begins with public permission and exists by public approval” (http://awpagesociety.com/site/historical-perspective, n.d.). What is profoundly different today is the ability of stakeholders to get access to more information more quickly and easily and to share it with others instantly, potentially transforming public opinion about an enterprise and its operations virtually overnight.

Social Purpose and Corporate Character

The Arthur W. Page Society’s 2012 report, Building Belief: A New Model for Activating Corporate Character & Authentic Advocacy (2012b, p. 7), posits that enterprises must adhere to a strong and admirable corporate character in order to earn stakeholder trust. Page defines corporate character as the unique, differentiating identity of the enterprise, as determined by its mission, purpose, values, culture, strategy, brand, and business model. As the expectation increases that the enterprise must operate transparently and responsibly, while serving a social purpose, defining and aligning corporate character are critical.

In the 2016 Edelman Trust Barometer, 80 percent of respondents said they expect businesses can both increase profits and improve economic and social conditions in the communities in which they operate. It offered Tupperware as a prime example that has a global sales force in countries all over the world, including China, India, and Indonesia, where 3.1 million women can earn much-needed income to help drive sales revenue for the company. Additionally, it found that stakeholders respond positively to CEOs who can both earn profits and provide societal benefits; trust in CEOs has risen in the past five years.

Kanter (2011) noted that great companies extract more economic value by creating frameworks that “use societal value and human values as decision-making criteria” (p. 5) and meet stakeholder needs in a variety of ways. Social purpose and values are “at the core of an organization’s identity” (p. 11). Therefore, seeking legitimacy or public approval by aligning enterprise objectives with social value is a business imperative. As Kanter (2011, p. 10) noted, “Only if leaders think of themselves as builders of social institutions can they master today’s changes and challenges.”

The Rise of Technology

Much of the change that is affecting the business environment is driven by technology. According to the International Data Corporation (2015), 3.2 billion people, or 44 percent of the world’s population, now are connected on the Internet. This number is growing rapidly in every part of the world, driven by the explosion of mobile technology. Half of the world’s population now has a mobile phone subscription, compared to just one in five 10 years ago (GSMA 2015).

The availability of inexpensive smartphones and laptops has made the Internet accessible to a whole new demographic. More than half of the population in each of the nations surveyed by the Pew Research Center (February 22, 2016) reported owning a mobile phone. The same study reported more than 9 in 10 own mobile phones in Jordan (95 percent), China (95 percent), Russia (94 percent), Chile (91 percent), and South Africa (91 percent). The advent of tablets and smartwatches has also broadened the spectrum of Internet usage (Kah Leng 2016).

Each mobile device is not simply a receiver, but a potential global transmitter. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, landline telephone penetration is near zero as the number of mobile devices has exploded, with many mobile owners using cell phones to take pictures/videos, send text messages, or do mobile banking (Pew Research Center 2015, April 15). Smartphones have helped reduce the number of people who do not have access to a bank account by 20 percent in the past three years (The World Bank 2014). As The World Bank noted, “As seen in sub-Saharan Africa, mobile money accounts can drive financial inclusion” (p. 3).

According to the IDC report, the mobile ecosystem is a tremendous economic driver; in 2014, the mobile industry accounted for 3.8 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP).

Software has had an impact on how businesses operate. In 2011, Andreessen contended that “software is eating the world,” (p. 2) and software companies “are poised to take over large swathes of the economy” (p. 6). Four years later, Hendricks (2015, p. 1) wrote that now that software has eaten the world, it is starting to eat the company. In the same way that iPhones and iPads have turned into efficient ways to never need a personal assistant, Hendricks notes that software has slowly begun to make enterprises of all sizes leaner.

Innovation enabled by software is disrupting businesses of all sorts and transforming the economy. Google, Amazon, Uber, Airbnb, and others are transforming entire industries. In his 2015 book, Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future, Martin Ford, the founder of a Silicon Valley-based software firm, argues that “advancing information technology is pushing us toward a tipping point that is poised to ultimately make the entire economy less labor intensive” (p xvii).

A Deloitte study (2015b), on the other hand, concludes that “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the past 150 years.” And in 2016, IBM CEO Ginni Rometty, in a letter to the U.S. President-elect Donald Trump, argued that there are many “new collar” jobs being created in technology that require training, but not a college degree (IBM 2016d).

Similarly, social media powered by technology have had a tremendous impact on business. In this smaller, flatter global world, social media have not only changed the way people access information and communicate with each other, but also created new communities of interest that exert powerful influence on existing and emerging institutions. Indeed, stakeholder groups have become more empowered, emboldened, and organized (Arthur W. Page Society 2016).

This speed of innovation correlates with technology’s impact on society and people’s behavior, and the speed with which it drives change. Despite several industry predictions that Moore’s Law4 is dying (Simonite May 13, 2016), researchers and companies like IBM and Google argue that the speed of innovation is not dying but taking a shift (The Economist 2016). This shift looks at innovation in terms of computing performance instead of transistor count.

Senior Vice President of Research and Marketing Intelligence of the Computing Technology Industry Association (CompTIA) Tim Hebert said, “Much of this growth [in the technology sector] can be attributed to the current trends in cloud computing, mobility, automation and social technologies that are reshaping businesses large and small (CompTIA 2016, p. 5).” The CompTIA’s Cyberstates 2016 report attributes 7.1 percent of the overall GDP to the U.S. tech industry. Other important factors are attributed to the growth of the “Internet of Things” (IoT), and the increased focus of cybersecurity.

Privacy and Cybersecurity

Businesses and governments have never been more reliant on technology and information sharing. Yet these same tools and interconnectedness make personal, business, and public property more vulnerable to attack than ever before.

In addition to traditional criminal networks and nonstate actors, state-sponsored cyber-attacks have become more frequent. According to the IBM Cyber Security Index (2016b), almost every industry saw an increase in security attacks in 2015, with companies experiencing a 64 percent increase in security incidents from 2014 to 2015; the most heavily hit industry was health care followed by manufacturing. The IBM Cost of Data Breach Study (2016a) found the average total cost of a data breach grew from $3.8 to $4 million. According to the Arthur W. Page Society (2016), “attacks target critical infrastructure systems, consumer data, business strategy and state secrets, creating new operational and reputational risks with which private and public sectors alike have struggled to keep up” (p. 8).

By 2018, more than half of all enterprises will use security service firms that specialize in data protection, security risk management, and security infrastructure management to enhance their security postures, with mobile security becoming a higher priority for consumers from 2017 onward (Gartner 2014). Morgan (2015) consolidated estimates by IT industry research and analyst firms to predict the worldwide cybersecurity market will grow from $75 billion in 2015 to $170 billion by 2020.

Societal Changes

Beyond these technological changes, there are also societal changes afoot in this new digital era that affect the way our stakeholders consume, interpret, and digest information. According to The New CCO, embracing diversity is a progressively important strategic imperative as business decisions and operations benefit from diversity of thought and inclusiveness.

Today, it seems the media news cycle is consumed by instances of intolerance of differences in communities across the world, which are being countered by greater efforts to drive toward equality in all societies. To be successful, the enterprise must understand and meet the needs of increasingly diverse internal and external stakeholders.

Diversity

Diversity is an important consideration for today’s workforce and according to Deloitte (2014), it is not just visible aspects of diversity, but also diversity of thinking (more on this will be covered in Chapter 6). Diversity, then, is the measure and inclusion is the mechanism—both are needed to access top talent, drive performance and innovation, retain key employees, and understand companies. As the workforce is more multicultural than ever, a diverse workforce is not a program or marketing campaign, but “is a company’s livelihood, and diverse perspectives and approaches are the only means of solving complex and challenging business issues” (Deloitte 2014, p. 92).

Age. The global workforce is becoming younger, older, and more urbanized (Deloitte 2014). The two greatest demographic trends that will impact the world in which we operate are the world’s aging population and the rise of millennials (Pew Research Center 2009). The proportion of older adults in the labor force, referred to as the “grey ceiling,” has been growing steadily over the past decades. In 2016, Millennials (ages 18 to 34 in 2015) surpassed the Baby Boomers (ages 51 to 69) (Fry 2016). Generation X (ages 35 to 50) is projected to pass the Boomers in population by 2028; until then, this demographic is projected to remain the “middle child” of generations—caught between two larger ones (Fry 2016). Research from the McKinsey Global Institute (2012) suggests that, by 2020, the world could have too few college-educated workers and that, in advanced economies, up to 95 million more low-skill workers than employers will be needed.

Gender. In business, the topic of gender equality continues to be an agenda item for most boardrooms. Women continue to participate in labor markets on an unequal basis compared to men. Gender differences in laws affect both developing and developed economies; almost 90 percent of 143 countries studied (UN Women 2015) have at least one legal difference restricting women’s economic opportunities. Societal factors and more nuanced perceptions of gender also contribute to inequality in the workplace.

Despite women’s gains, a large gender pay gap still exists. In 2013, women in the United States working full time, year round earned 78 percent of what men working equivalently earned (White House 2015). This number has been static for the past 15 years. The White House report on the gender pay gap suggests business and the economy can be improved, as well as worker productivity and retention, when workers are in jobs well suited to their skills and qualifications and policies ensure fair pay.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ). The drive toward great equality in the LGBTQ community is also a major force within almost all cultures across the world. Nearly two dozen countries currently have national laws allowing gays and lesbians to marry, mostly in Europe and the Americas (Pew Research Center 2015, June). A meta-analysis of 36 research studies found that “less discrimination and more openness, in turn, are also linked to greater job commitment, improved workplace relationships, increased job satisfaction, improved health outcomes, and increased productivity among LGBT employees” (Badgett et al. 2013, p. 1).

Race. In the United States, Americans are more racially and ethnically diverse than in the past, and projected to be even more so in the coming decades (Cohn and Caumont 2016). However, there are challenges as companies and individuals are still battling racism. A recent Pew Research Center study (June 27, 2016) found two-thirds of black adults say blacks are treated less fairly than whites in the workplace. More than half of respondents to a 2015 survey (Pew Research Center 2015, August) reported racism is a “big problem” in today’s society, and the United States needs to continue making changes to give blacks equal rights with whites. As enterprises become more global, more multiracial, and more multicultural, more are focusing on diversity and inclusion in the workplace, and tying compensation to recruitment and retention. The evidence is clear—diverse companies perform better (Diversity Matters 2015).

Religion. The religious profile of the world is rapidly changing, driven primarily by differences in fertility rates and the size of youth populations among the world’s major religions, as well as by people switching faiths (Pew Research Center April 2, 2015). The Pew study predicted that by 2050:

• The number of Muslims will nearly equal the number of Christians around the world.

• In Europe, Muslims will make up 10 percent of the overall population.

• India will retain a Hindu majority but also will have the largest Muslim population of any country in the world, surpassing Indonesia.

• In the United States, Christians will decline from more than 75 percent of the population in 2010 to 67 percent in 2050, and Judaism will no longer be the largest non-Christian religion. Muslims will be more numerous in the United States, than people who identify as Jewish on the basis of religion.

• Four out of every 10 Christians in the world will live in sub-Saharan Africa. (2)

The most important finding of all is this:

Atheists, agnostics, and other people who do not affiliate with any religion—though increasing in countries such as the United States and France—will make up a declining share of the world’s total population.

For those who see the divisiveness and violence attributed to religious clashes and conclude that secularism is the answer, the trends are not on their side. Yale University theologian Volf (2016) argues in Flourishing: Why We Need Religion in a Globalized World that “globalization and religions, as well as religions among themselves, need not clash violently but have internal resources to interact constructively and contribute to each other’s betterment.” As part of Princeton University’s Faith and Work Initiative, research by Miller and Ewest (2010, p. 7) contended that understanding religious/spiritual identity at work can bring potential business benefits. These include “increased diversity and inclusion; avoidance of religious harassment or discrimination claims; respect for people of different faith traditions or worldviews, and possibly a positive impact on ethics programs, employee engagement, recruiting and retention.”

Differing Value Systems

The rise of authoritarian capitalism, combined with gridlock and ineffectiveness in the Western democracies, is creating challenges for global business enterprises. Some believe state capitalism may be emerging as a preferred economic system in developing countries, based on the perceived success of that system in China. According to the Arthur W. Page Society (2016), others believe that with economic progress will come more pressures for liberal democracy in China, Russia, the Middle East, and the developing world. Roughly 6 in 10 Chinese see growing international business ties as a way to improve local incomes (Pew Research Center 2014). Such sentiment may be rooted in China’s recent experience. Wages have grown an average of more than 10 percent annually for more than a decade at a time when the country’s merchandise exports were rising an average of 15 percent. In the Western democracies, political polarization and slow economic growth have combined to create voter disenchantment and disenfranchisement. This is driving a sentiment that globalization is not good for business. According to the Pew Research Center (2016, June 13), terrorist attacks, refugee crises, and economic decline are raising support for nationalism and focusing on their development rather than helping allies. The success of the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the Trump election in the United States both seemed motivated, at least in part, by concerns about job losses to and immigration from less-developed countries.

Health Care and the Environment

Three of the 17 sustainable goals outlined in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015) were health care, clean water and sanitation, and climate action. While the goals are fairly general, they are not mutually exclusive. A change in one, such as improving clean water, can have a dramatic impact on others like health care and the environment. The issues outlined by the UN should be considered by all enterprise CEOs in preparation for tomorrow’s environment.

Health Care

In 2015, Deloitte released its Global Health Outlook report stating a “tug-of-war” exists between competing priorities of trying to meet the increasing demand for health care and reducing the rising costs (p. 1). Globalization is likely to bring issues as some countries struggle to ensure sufficient resources as developing markets are expanding, especially Asia and the Middle East. One given is that global health care spending will continue to increase. The enterprise needs to adapt to increased spending and changing health care needs. Businesses must contend with changes to health care policies and practices, including changes to government programs and movement toward consumer-driven health care. Radnofsky (2016) notes that 20 major enterprises (e.g., American Express, Macy’s, and Verizon Communications) have allied to share information about members’ employee health spending and outcomes. Down the road, they may form a purchasing group to negotiate lower prices.

Global health risks also impact businesses. According to the World Health Organization (2009), the leading global risks for mortality, responsible for 63 percent of all global deaths, are high blood pressure, tobacco use, high blood glucose, and physical inactivity (all noncommunicable diseases or NCDs). Five leading risk factors (childhood underweight, unsafe sex, alcohol use, unsafe water sanitation, and high blood pressure) are responsible for one-fourth of all global deaths. According to the Harvard School of Public Health and World Economic Forum (September 2011), over the next 20 years, NCDs will cost more than US$30 trillion, representing 48 percent of global GDP in 2010, and push millions of people below the poverty line. Nearly half of all business leaders surveyed worry at least one NCD will hurt their company’s bottom line in the next five years and the enterprise is a key change agent facilitating the adoption of healthier lifestyles, issues that cause “decreased productivity in the workplace, prolonged disability, and diminished resources within families” (p. 5).

Clean Water

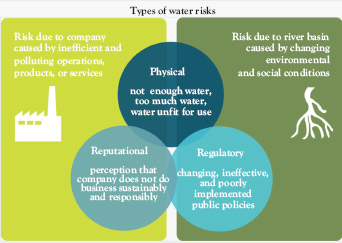

In 2010, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution that clean drinking water and sanitation “are essential to the realization of all human rights” (UNDESA 2015, p. 1), specifically water that is “sufficient, safe, accessible, physically accessible, and affordable” (UNDESA 2015, p. 4). According to Mekonnen and Hoekstra (2016), two-thirds of the world’s population lives under conditions of “severe” water scarcity at least one month of the year, with nearly half living in Asia. Even though the 2015 Global Risks Report by the World Economic Forum (WEF) ranked water crisis as one of the three highest concerns to society worldwide, a WEF survey of executives found water only ranked 13th. According to members of the 2030 Water Resources Group (2009), water issues will affect nearly every business sector. In the CEO Water Mandate, the UN Global Compact (2016) identified three water risks (see Figure 1.1): physical, reputational, and regulatory. Physical risks can occur by having too much water, not enough water for production or processing, or water that is unfit for use. Water scarcity can also impact energy and food production, not to mention increase costs; however, more companies are implementing water reduction policies. Companies can also be affected by reputational risks as stakeholders are demanding companies be responsible and sustainable. Regulatory risks can occur when infrastructure or the lack of water quality regulations have an effect on the costs to do business as water sources must be cleaned prior to use.

An important factor in clean water is its cost and economic impact. The World Health Organization (2016) found achieving the goal for halving the proportion of people without sustainable access to both improved water supply and sanitation would give a triple return on investment. Poor water policies, lack of oversight, increased water demand, increased urbanization, lack of funding, inconsistent water policies across countries, and lack of stakeholder involvement (2030 Water Resources Group 2009) are some of the identified water challenges of the future. Many enterprises are affected by water shortages or the potential for water scarcity. One example of this is SABMiller, the world’s second-largest brewer measured by revenue, which enacted measures beyond simply reducing water use to focus on long-term water use (3p Contributor 2015). In 2004, Pepsi Bottling and Coca-Cola closed down plants in India that local farmers believed were in competition for water (2030 Water Resources Group 2009). McKinsey & Company, a member of the 2030 Water Resources Group, predicted that water would be a strategic factor for most companies noting, “All businesses will need to conserve, and many will make a market in conservation. Tomorrow’s leaders in water productivity are getting into position today” (p. 31).

Figure 1.1 Interrelationships of types of water risks

Source: UN Global Compact: http://ceowatermandate.org/why-stewardship/stewardship-is-good-for-business/

In a PwC 2014 survey, 46 percent of CEOs agreed that resource scarcity and climate change will transform the enterprise the most over the next five years, especially dealing with a rise in energy prices (despite a time when fossil fuel prices are low) and increasing government regulation. According to the Climate Vulnerability Monitor, losses attributed to climate change are predicted to increase rapidly with an estimated 3.2 percent of GDP in net average global losses by 2030 (Fundacion DARA Internacional 2012). In 2012, PwC released a climate change report suggesting radical enterprise action is needed to plan for a warming world (Confino 2012). According to Confino, CEOs need to be prepared to tackle climate change issues: “Sectors dependent on food, water, energy or ecosystem services need to scrutinize the resilience and viability of their supply. More carbon-intensive sectors need to anticipate more invasive regulation and the possibility of stranded assets” (p. 12). Siegel (2013) maintains that “without a doubt” the number one impact of climate change on business will be “uncertainty,” as this area’s future is hard to predict (p. 7).

Sustainability is an important force of business, as consumers are increasingly demanding enterprises become more sustainable. The UN Global Compact (Accenture CEO Study 2013) found that 93 percent of CEOs believe that sustainability will be important to the future success of their business, but only 34 percent report making sufficient efforts to address global sustainability challenges. The key, though, lies in the hands of the consumer. While the report found investors will not be the ones pressuring growth, more than half of respondents said the customer is key to influencing the approach, and 87 percent said the reputation of sustainability is important in consumer purchasing decisions. A McKinsey & Company (2014) study reported reputation management related to sustainability is a challenge because, while reputation management is a top reason for enterprises to address sustainability, many are not pursuing these value-added types of reputation-building activities. Further, they note that the most effective sustainability programs are building in strong performance processes, aggressive internal and external goals, a focused strategy, and leadership buy-in.

Summary

With the dramatic changes in society in this digital age and for the future, understanding the interwoven factors that impact society is critical. Technology will continue to grow and change as innovations become more diffused through society, and processors and equipment become faster, smaller, and cheaper. More community-driven initiatives, and the proliferation of social media platforms, demonstrate that power has shifted to the stakeholder. With the influx and success of start-ups, traditional business models are changing. Society is changing dramatically and, as people are moving, shifting, and ideologies are melding, understanding and anticipating needs will be key to enterprise success. Ensuring fairness and a diverse and inclusive (D&I) workforce will be critical. The environment will play a starring role as the enterprise needs to think about how costs and demands for sustainability will impact the future. With all these changes, the role of the CCO has never been as important as it is today. The Arthur W. Page Society report, The New CCO: Transforming Enterprises in a Changing World (2016), describes the need for effective communication today and for the future. The CCO must be an integrator, a builder of digital engagement systems, and a strategic leader and counselor. With these changing times, it is certain that change is inevitable. Choosing to ignore change is not an option.

1 As noted earlier, we use the term “enterprise” to mean large businesses and/or corporations that have large local, regional, national, and global subsidiaries. This is not to demean smaller organizations, who often have the same communication concerns and problems, but not to the same scale.

2 Throughout this volume, the term “communication” is used when discussing the role of communication strategies and its function in the enterprise. Communications refer to the actual channels employed in executing those strategies (such as written, spoken, and broadcast).

3 Stakeholders include anyone who has a stake in the activities of an enterprise (e.g., employees, customers, investors, communities, public interest groups, and regulators).

4 Moore’s Law posits that the number of transistors per square inch on integrated circuits, and consequently the processing power they produce, doubles every year.