Chapter 22

A Central Bank

Really, we cannot go on in this way. Financial flurries and squeezes which are of such frequent occurrence at the great money centers of the country are the legitimate offspring of a bad financial system. These things do not occur in European countries where they have their banking system on a solid and enduring basis, under complete government control. Until we adopt a central bank of issue, or something like it, there can be no permanent relief.

—Senator Henry C. Hansbrough of North Dakota, November 23, 19071

Through the tortuous process of financial crisis and civic reaction, public sentiment built inexorably toward acceptance of the idea of a central bank in the United States. By late November 1907, newspapers were declaring that the crisis had ended.2 Yet already it was apparent that the Panic of 1907 had crystallized a change in attitude: as had been true for a century or more, the problem in a panic was the insufficiency of money and credit; the novelty of 1907 was to shift attention to the structure of the financial system.

However, what kind of bank would it be? Paul Warburg, an investment banker with Kuhn, Loeb, advocated a truly centralized bank such as existed in Britain, France, and Germany—one institution that could command the financial muscle to serve a growing economy and respond decisively in the event of a crisis. Populists, such as William Jennings Bryan, recoiled from the powers exercised by J. P. Morgan and George B. Cortelyou and sought the decentralization of bank reserves and money‐making power. Populists said that decision makers on the Eastern Seaboard had neglected the needs and wants of the interior.

Governance of a central bank also proved contentious: bankers wanted a prominent role in running the institution; leaders in business and labor wanted to exclude the bankers in the belief that bankers would co‐opt the central bank for their own benefit. The debate whipped up older antagonisms between Wall Street and Main Street. And then back to money: Whose obligation would paper money be? Populists and progressives sought the backing of the U.S. government. Conservatives, fearing inflation if the government backed the currency, favored a continuation of the same money system since the Civil War: banks would issue their own notes, backed by bonds placed on reserve with the government.

In short, what emerged after the elections of 1912 was a multidimensional multiparty negotiation over the design of a U.S. central bank.

Shift in Orthodox Thinking

The Panic of 1907 triggered immediate reflections on the potential role of government in managing bank reserves and stabilizing the financial system. Shortly after the panic, Republican Senator Henry Hansbrough of North Dakota mooted the establishment of a central bank for the United States—to be headquartered in Chicago “near the center of commerce and agriculture, as far away from the speculative atmosphere as possible.”3 Yet Senator Nelson Aldrich, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, demurred, claiming “no disposition to hurry the consideration of so important a subject.” Congress reflected a wide diversity4 of opinion about a possible central bank and the approaching federal elections in 1908 discouraged the passage of important legislation.5 Democrats in Congress offered legislation that proposed the establishment of a central bank, although Roosevelt considered it too inflationary; the Republican majority defeated the bill. Nevertheless, Roosevelt himself began to muse aloud about the benefits of establishing a central bank in the United States, as he wrote in November 1907:

I am inclined to think that from this side, a central bank would be a very good thing. Certainly I believe that at least a central bank, with branch banks, in each of the States … but I doubt whether our people would support either scheme at present, and there is this grave objection, at least to the first, that the inevitable popular distrust of big financial men might result very dangerously if it were concentrated upon the officials of one huge bank. Sooner or later there would be in that bank some insolent man whose head would be turned by his own power and ability, who would fail to realize other types of ability and the limitations upon his power, and would by his actions awaken the slumbering popular distrust and cause a storm in which he would be as helpless as a child, and which would overwhelm not only him but other men and other things of far more importance.6

Necessary, But Insufficient

To stem political fury about the Panic and buy time for more thoughtful institutional design, Senator Nelson Aldrich mustered support for the Aldrich–Vreeland Act in May 1908, which chartered the National Monetary Commission. Under cover of the Commission, Aldrich embarked on a nearly three‐year search for a feasible design. Gradually the staunch conservative accepted the need for a central bank, influenced particularly by visits to European institutionsa and by the patient lobbying of Paul Warburg for reforms adopting their model.

Meanwhile, Populist anger about the Panic took shape in the advocacy of government guarantees of bank deposits. Eight states—mainly in the West and South—adopted such legislation from 1908 to 1917. And by the federal elections in 1908, national deposit guarantees were a leading plank in the platform of the Democratic presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan.

In response, Taft, Roosevelt, and the Republican legislators promoted the idea of a postal savings bank system. This system would authorize local postmasters to accept deposits up to $500 to be guaranteed by the U.S. government. The system would reinvest the deposits in interest‐bearing assets (mainly accounts at national banks) and retain one‐half of a percent to cover the cost of administering the system.

This was hardly equal to a full‐blown government guarantee of bank deposits. But its advocates hoped that it would win some support in the 1910 elections from farmers, immigrants, and small‐balance savers. Taft signed the enabling act on June 25, 1910, although it proved insufficient to avert the Democratic Party victory in November 1910. Nevertheless, the Postal Savings Act proved to be a significant precedent toward broad government guarantee of deposits enacted in 1933. Subsequently, the opposition of bankers led to the termination of the postal savings system in 1971.

Jekyll Island

A pivotal event for Aldrich was a secret conference of financiers and politicians on Jekyll Island, Georgia, in November 1910. That meeting produced a design for a “National Reserve Association” that made its way into the final report of the National Monetary Commission. Senator Aldrich claimed the design was his, although it was strikingly like a plan advocated by Paul Warburg, partner in the firm, Kuhn, Loeb, earlier in the decade. Warburg was present at Jekyll Island, as was Frank A. Vanderlip, then president of National City Bank, who is credited with drafting the proposal to emerge from that conference. Others at the conference were A. Piatt Andrew (assistant secretary of the Treasury), Henry P. Davison (partner in J.P. Morgan & Company), Charles D. Norton (president of First National Bank of New York), and Benjamin Strong (vice‐president of Bankers Trust). As progressives would later argue, these successors to J. P. Morgan, James Stillman, and George F. Baker imprinted the views of the “money trust” on the proposed National Reserve Bank. Yet in broad outline, the product of Jekyll Island bore several similarities to the central bank that President Woodrow Wilson, Treasury Secretary Carter Glass, and the Democrats would later claim credit for establishing.

Two months later, on January 16, 1911, Senator Aldrich formally submitted to the National Monetary Commission (and the public) a draft of legislation to establish a National Reserve Association. This draft was Aldrich’s first step toward rallying political support, refining the text, and identifying opponents. A revised draft was included in the Commission’s final report.

Report of the National Monetary Commission

The National Monetary Commission published its report on January 8, 1912, after a long gestation since founding in May 1908. The significance of the 24‐volume report was its forthright criticism of the existing laws and institutions for banking and currency—the old orthodoxy. The report recommended starting afresh with the establishment of a “National Reserve Association” that would promote cooperation among banks.

The basis for the Commission’s recommendations was a list of 17 “defects of the banking system, which were largely responsible for [the] disasters”7 of the Panic of 1907. From the discussion in earlier chapters, many of these defects will be familiar to the reader and for brevity can be clustered into four general groups.

First, several defects dealt with issues regarding the concentration and immobility of bank reserves. The required reserves of banks were “pyramided” up to the big banks in New York City. And rescue capital was relatively immobile. Banks could not turn to a large reservoir of funds if they experienced a run. Laws restricted the use of bank reserves. And banks lacked the means to augment their reserves or expand loans to meet unexpected needs.

Second, the Commission noted the absence of a national coordinator who could view the entire country and even international conditions to deploy reserves more fairly and “enforce adoption of uniform standards with regard to capital, reserves, examinations, and the character and publicity of reports.”8 Without mentioning J. P. Morgan, the Commission clearly had in mind creating a powerful central force for intervention in the event of crises.

Third, the absence of a central bank with which to discount commercial paper led to episodes of credit illiquidity; and in buoyant times the absence motivated banks to place their surplus reserves into the call loan market in New York. The Commission grumbled about the lack of “equality in credit facilities between different sections of the country, reflected in less favored communities, in retarded development, and great disparity in rates of discount.”9

Finally, the report criticized existing laws as inadequate to the needs of the current economy. Drawing particular attention were the National Banking Acts of the Civil War Era, and the Independent Treasury Act of 1840 that separated government from banking. The laws were restrictive and resulted in “discrimination and favoritism.”10

To remedy these issues, the Commission recommended chartering a “National Reserve Association” to be sustained by a capital subscription of $100 million from all participating banks and by a contingent call for an equal amount in the event of a crisis. Membership in the association would be voluntary and open to all national banks, state banks, and trust companies. The National Reserve Association would consist of numerous local associations, chartered as branches of the national organization. Banks would elect the directors of the local associations. The United States would be divided into 15 districts, which would elect directors of the National Association. The Secretaries of Treasury, Agriculture, Commerce, and Labor, and the Comptroller of the Currency would be ex officio members of the National board—reflecting the need “to secure a proper recognition of the vital interest which the public has in the management of the association.”11 The Governor of the National Reserve Association would be appointed by the president of the United States for a term of 10 years.

The important functions of the local branches would be to discount commercial paper of their members, to clear checks among members, to facilitate domestic exchanges with different regions of the country, and to assure the redemption into gold of the banknotes of the members. Even though the National Reserve Association would be a privately‐owned corporation with stockholders, it would hold a special government charter to serve as the fiscal agent and financial depository of the U.S. government—this mirrored the status of the Bank of England (and the earlier Bank of the United States). The National Reserve Association would have the power to fix uniform rates of discount across the United States. Finally, all new currency would be issued by the National Reserve Association, against which it would hold gold reserves not less than 50 percent of the value of such currency.

In support of its recommendations, the Commission argued that the National Reserve Association would reduce expenses, respond more effectively to crises, and generally deal with the 17 defects it highlighted.

The Commission’s report contained the draft of a 29‐page bill that would enact its recommendations. The Commission’s draft won the endorsement of the American Bankers Association and the National Citizens’ League for the Promotion of a Sound Banking System. Aldrich introduced the bill in the Senate on January 9, 1912. The draft assumed the nature of a legacy for the venerable senator.

Unfortunately, the Aldrich draft proved to be dead on arrival, reflecting the rapidly changing political climate and the fact that Aldrich had recently retired owing to ill health. The Republican Party platform for 1912 gave scant attention to the proposal. And the Progressive Party platform openly opposed it, saying it ceded control to private hands rather than to the government.

Nevertheless, the publication of the National Monetary Commission’s report and Aldrich’s subsequent draft legislation marked a dramatic turn in the conversation about financial reform. The crises of the nineteenth century had focused reform discussion on the currency of the United States, whereas the new report focused reform on the structure of the banking system as the first step to achieving stable currency. Historian Richard McCulley attributed this sea change to Paul M. Warburg, a banker with Kuhn, Loeb who had been writing and debating reform for over a decade:

Warburg argued that the priority for financial reform was the development of a discount market to replace the call market as the principal outlet for the placement of banks’ liquid funds in the United States. That could be accomplished, he explained, through the creation of a central bank with rediscounting powers that favored commercial bills and discriminated against call loans on stock exchange collateral. In Warburg’s vision, therefore, the transformation of the nation’s money market depended on the creation of a central bank; conversely, the effectiveness of the central bank depended on the creation of a discount market that would become the main vehicle for monetary policy to influence credit conditions in the United States … . [ U]nder Warburg’s influence, monetary reform came to be seen as inextricably linked to the structural reform of the US money market and its relationship to the banking system.12

New Political Landscape

The failure of Aldrich’s draft reflected a political reality that dawned with the midterm elections of 1910: public support for the Republicans’ coalition of conservatives and progressives was fading. Congress reflected a growing split between the two sides. For instance, in 1909, Congress passed the Payne–Aldrich Tariff, which raised duties on a range of imported goods and inflamed progressives and Democrats who saw the tariff as crony capitalism, a handout of import preferences to Nelson Aldrich’s business friends. One progressive senator openly accused Aldrich of profiting from the tariff, which Aldrich vehemently denied.

The populist–progressive impulse following the Panic of 1907 assured a majority in opposition to Aldrich’s proposed National Reserve Association. The Panic had polarized voters and their elected representatives, producing gridlock on financial reform. As things stood, banks would be prevented from branching or doing business across state lines, and there would be no central bank. Paul Warburg wrote that the polarization “led to an almost fanatic conviction that the only hope of keeping the country’s credit system independent was to be sought in complete decentralization of banking.13

Also, the presidential administration changed. Theodore Roosevelt had pushed for priorities in conservation and favored regulation of trusts by means of negotiation rather than lawsuits. President Taft departed from the policies of his predecessor both in substance (he abandoned conservation and endorsed a Constitutional amendment to permit taxation of incomes) and style (by temperament, Taft recoiled from using the White House as a “bully pulpit” from which to mobilize supporters).

Into this breach came Woodrow Wilson. He was a progressive, favoring technocratic expertise to establish good public policies. But he also had to retain in his camp Populists led by William Jennings Bryan, and Southern legislators who were committed to Jim Crow discrimination against African Americans. Wilson’s gift was an ability to broker compromises that would pass laws. Seeking to exploit the momentum of the election results, he marshaled party leaders in the House and Senate to accelerate progress on five progressive priorities: lower tariffs, a new income tax, direct election of U.S. senators, stronger antitrust laws, and reform of the financial system.

The cumulative effect of the Panic of 1907, the recession of 1910–1911, the restoration of Democratic Party power in the House, the Stanley Investigation, the Pujo Investigation, Aldrich’s dilatory progress on financial reform, rising friction between progressives and conservatives, and the Republican Party’s dramatic split in 1912 over the competing candidacies of Roosevelt and Taft swept the Democrats to control of both houses of Congress and the White House in 1912. It was a crushing denouement to what in 1906 seemed to be a durable political franchise for Republicans.

A Reserve System Emerges

Wilson’s push for financial reform legislation stimulated a burst of lobbying and political wrangling by members of Congress. The first to take the initiative was Carter Glass, a representative from Lynchburg, Virginia who would assume the powerful role of chairman of the House Banking Committee. Glass met with Wilson on December 26, 1912 to sketch the outlines of a new central bank.

Carter Glass advocated a system of 15–20 regional reserve banks that would be relatively independent, but under the supervision of the federal government. Indeed, the degree of coordination among the regional reserve banks remained vague. The reserve banks would be owned by the banks in their district and would hold government deposits of gold with which to back notes (currency) that would replace the old national bank notes. The reserve bank would discount commercial paper, thus enabling banks to avoid the threat of illiquidity in a panic. Glass felt that private bankers should govern the reserve banks, owing to their expertise. And he posited that notes of the reserve banks should be obligations of the banks, not the U.S. government. “I pointed out the unscientific nature of [U.S. government obligations.]” Behind the Federal Reserve Note would be the liability of individual banks, the double liability of bank stockholders, the gold reserves, the reserves of discounted commercial notes, and the liability of member banks. “There is not, in truth, any government obligation!”14

Where Aldrich’s plan called for a much more centralized reserve bank with up to 15 branches, Glass’s plan emphasized decentralization into maybe 15 relatively autonomous banks. Glass wanted to prevent the aggregation of bank reserves in New York City. Instead, bank reserves would be held in the regional reserve banks. Glass believed that such decentralization harkened to Democratic Party values reaching back to Andrew Jackson and Thomas Jefferson.

When Wilson asked Glass who would oversee the regional reserve banks, Glass nominated the Comptroller of the Currency, who was already in charge of the National Banking System. However, Wilson wanted a federal governing structure of the system, in the form of a board to whom the regional banks would report. Glass was surprised, but after reflection began working on draft legislation to introduce upon Wilson’s inauguration on March 4.

The draft that Glass circulated met stiff opposition from both bankers and populists. For instance, Benjamin Strong, president of Bankers’ Trust, thought that it created too many reserve banks, gave too much power to political appointees and others who had no skill or experience in financial matters, would “return to the heresies of Greenbackism and fiat money,” and ultimately would create moral hazard and political meddling.15 As for the populists, William Jennings Bryan informed President Woodrow Wilson of his opposition to the bill on May 19, 1913, arguing that he couldn’t support it because it permitted bankers onto the proposed Federal Reserve Board and enabled national banks to issue currency. “The government alone should issue money,” he said.16

Competing Designs

Next came interventions from William Gibbs McAdoo, Wilson’s new secretary of the Treasury. McAdoo had been a lawyer, securities dealer, president of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company, and outspoken progressive before helping to lead Wilson’s campaign for the presidency. McAdoo wanted Glass to add the secretary of agriculture as a member of the governing board of the system and wanted reserve banks placed no farther than a train trip from any point in the reserve district. And McAdoo urged that the regional institutions be titled Federal Reserve Banks—this pleased Wilson’s vision of a federal structure. McAdoo’s views continued to change, and by May amounted to Treasury Department control of a unitary central bank, with branches not unlike the venerable Subtreasury system that had been in use since the 1840s.

A third set of ideas came from Senator Robert Owen. He had been born in Lynchburg, Virginia into an affluent family as son of a railroad president. However, the Panic of 1873 followed by his father’s death ruined the family. Owen departed for Oklahoma Territory to serve as a teacher, lawyer, journalist, and Federal Indian Agent (he was part Cherokee). When Oklahoma was admitted to the Union as a state in 1907, Owen was elected to serve as one of the state’s two inaugural U.S. senators. Influenced by William Jennings Bryan, Owen brandished strong progressive views.

Senator Owen wanted the reserve banks to be distributed throughout the United States in districts independent of one another and controlled by the government. He argued that banknotes “should be the notes of the United States under the control of the Government and based on the taxing power, and that when these were loaned to the banks, they should be adequately secured by gold in fixed ratio and by United States bonds or commercial bills… . Some wished one bank, or as few as possible; others, from eight to twelve.”17

Wilson Decides

The differences among the competing drafts modeled the ideological divides then wracking Congress. Wilson had ordered Congress to remain in session during what was proving to be a sweltering Washington, DC, summer in 1913. Now, the whole effort seemed threatened by intransigence among the three proponents.

Wilson broke the deadlock by a compromise on June 17. He threw his support strongly in favor of eliminating banker representation entirely from the Federal Reserve Board and by asserting that Federal Reserve Notes should be obligations of the federal government. Wilson said, “Control … must be public, not private, must be vested in the Government itself, so that the banks may be the instruments, not the masters, of business and of individual enterprise and initiative.”18 This satisfied Bryan, though it shocked Carter Glass. To mollify Glass, Wilson also decided that the reserve banks should hold gold reserves backing up the currency at no less than 33 percent. With that, Glass and Owen agreed to compromise.

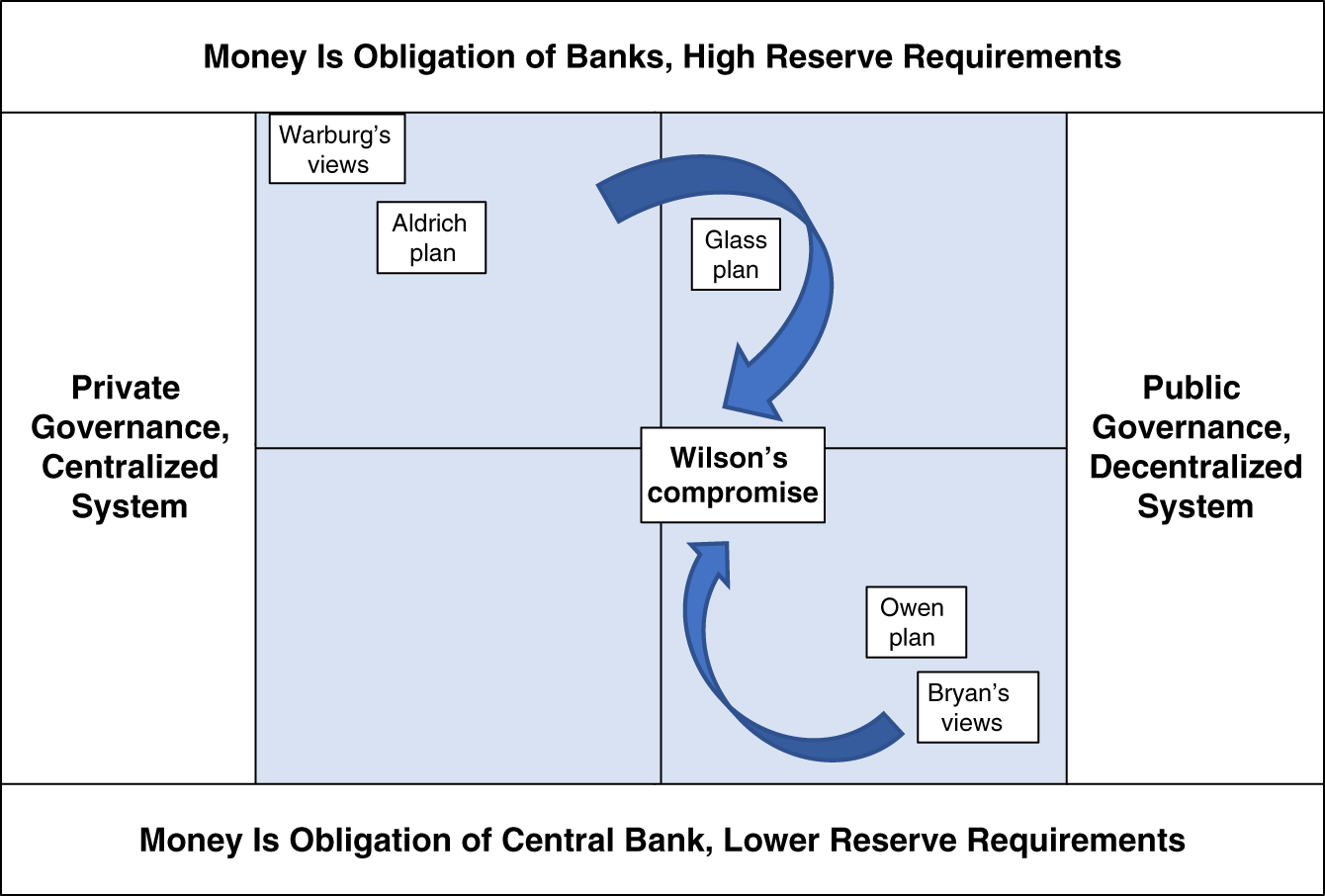

The Federal Reserve Act was published on June 20 and introduced in the House and Senate on June 26, 1913. Figure 22.1 depicts the positions of Warburg, Aldrich, Bryan, Glass, Owen—and, ultimately, Wilson—on two dimensions: (1) the extent of public versus private control of the central bank, and (2) the extent of centralization or decentralization in the holding of reserves and making of monetary policy. As the figure suggests, Wilson’s compromise divided the territory between Glass and Owen.

Figure 22.1 Wilson’s Compromise among Competing Proposals to Establish the Federal Reserve System

NOTE: McAdoo’s changing views are not easily depicted in this figure. In the final iteration, he favored public governance with a centralized system. Such a proposal was a nonstarter with Bryan, Glass, and Owen.

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, inspired by a figure in Conti‐Brown (2016), p. 23.

Glass began the final push in August with hearings in the House Banking Committee. There, three representatives from farm states stalled the bill with an amendment that would prohibit interlocking directorships among banks, a feature that Glass feared would make the bill unacceptable to a majority of the House. Therefore, Glass managed to move the bill to the Democratic Caucus, where a majority vote would bind all Democratic members to approve the bill. Privately, Bryan approached Glass to ask for an amendment that would allow the reserve banks to discount agricultural loans—Glass agreed and inserted some vague language to that effect. With that, Bryan expressed his support for the legislation and the opposition crumbled. The House approved the bill on September 18: 285 votes to 85.

In the Senate, Robert Owen encountered a range of amendments, including a government guarantee of deposits, a cut in reserve requirements, and permission for banks to trade securities and to discount agricultural loans. Again, opposition seemed to mount. Bankers started to circulate an entirely different plan for a central bank. And the American Bankers Association officially announced its opposition to the Federal Reserve Act.

Resistance began to fade after Wilson signed the Revenue Act of 1913, which sharply cut tariffs and established a progressive income tax,b both initiatives that progressive legislators could celebrate to their supporters. Outside support came from endorsements by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the New York Merchants Association. In addition, Owen agreed to modifications to allow agricultural paper to be eligible for discount, to reduce the number of Reserve Banks from 12 to 8, and to raise the gold reserve requirement for the Fed from 33 percent to 40 percent. On December 19, the Senate passed the bill by a vote of 54 to 34.

Wilson urged the conference of senators and representatives to align the terms of the respective bills speedily—he wanted to conclude the deliberations before the holiday recess, during which second thoughts might impede the subsequent adoption of the bill. The conference committee reported the revised bill back to the respective houses of Congress on December 22; the House approved it the same day and the Senate the next day. Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act on December 23, 1913.

Perfecting the Fed’s Federal Structure

Much of the tension among the progressives, populists, and Wall Street conservatives in Congress about the design of the new central bank focused on rule of the new institution. Conservatives wanted a centralized central bank close to the great money centers that would be run by people with expertise in money and banking—that is, bankers. Populists wanted a decentralized system of reserve banks whose reserve assets would be dispersed around the country and run by “Main Street” people. Progressives sought to distance the central bank from Wall Street, and wanted it controlled by the federal government’s public servants with some expertise in money and banking. How did the competing visions work out in practice?

President Woodrow Wilson and Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo had their work cut out for them. Implementing the Federal Reserve Act began with setting the size and location of the Federal Reserve Districts. This took eight months and summoned appeals and protests that lasted a year. An organizing committee, chaired by McAdoo and Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston, addressed the task of staffing and structuring the Federal Reserve System. They drew boundaries for 12 districts, each with a regional reserve bank. Only after confirming the districts could officials be appointed. The national oversight body, the Federal Reserve Board, was finally appointed in August 1914. Benjamin Strong, president of Bankers Trust, was appointed to be the first governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The 12 reserve banks opened on November 16, 1914.

Investment banker Paul Warburg was appointed to the first Federal Reserve Board in Washington, DC. He worried that ideologies and party politics would warp the technical operation of the new central bank.19 Indeed, the Fed’s governancec rendered it vulnerable to political considerations, a worry of Theodore Roosevelt and Nelson Aldrich. Anticorruption laws and sunshine provisions of the Progressive Era largely quelled fears of self‐dealing and capture by the banking industry. Yet remaining was the risk that the Fed would lose its independence and become an instrument of a presidential administration. For instance, Theodore Roosevelt feared that a central bank might monetize the government’s fiscal deficits or manage interest rates in ways to serve electoral benefits to the administration in power. As the following century revealed, such fears were foresightful.20

On the other hand, the Federal Reserve Act solved the problems outlined by the National Monetary Commission. It moved the setting of monetary policy and the lender of last resort function out of the private hands and into the public sector. The high cadence of banking panics that plagued the nineteenth century slowed sharply into the twentieth. When crises did arise, critics lamented the Fed’s over‐ or underreaction. Over many years, the Fed seemed slow to adapt to the ever‐changing and innovating financial sector. However, on balance the Fed served well the welfare of the nation.

Later, the Banking Act of 1935, which was a hallmark of New Deal monetary reforms, increased the central authority of the Federal Reserve Board and thus concentrated power over monetary policy. Where previously the 12 reserve banks could each set discount rates and conduct open‐market operations, the new act gave authority over such powers to the national board. The Banking Act also revised the governance of the national board by lengthening the terms of board members from one year to 14, thus mitigating the risk that a president might “pack” the board. Nonetheless, with the entry of the United States into World War II, the Fed again coordinated closely with the secretary of the Treasury, meaning that it lowered interest rates to help finance the government.

Not until 1951 did the Treasury Department and Federal Reserve Board agree to an “accord” that established the Fed’s independence from intervention by elected officials (or their delegates) into Fed policy. Although not enacted by Congress (and thus vulnerable to possible future changes), Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin said that the Fed and Treasury “reached full accord with respect to debt management and monetary policies to be pursued in furthering their common purpose and to assure the successful financing of the government’s requirements and, at the same time, to minimize monetization of the public debt.”21

Notes

- a. Overshadowing the debates about central banking in the United States were the examples of the central banks of Europe, all of which had been founded to serve the financial needs of monarchs and their imperial aspirations. The Bank of England (BoE) was the most prominent example, and the leading central bank in the world. The BoE had been privately owned since its founding in 1696, and operated under a special charter by the British government to act as its fiscal agent. The banknotes of the BoE became recognized as the British units of currency. Since 1866, the BoE served as the lender of last resort to ailing banks. A single institution without branches or subsidiaries, the BoE made no pretense toward representative engagement with regions or people beyond London’s Threadneedle Street or the leadership of Britain’s financial community.

- b. The act taxed annual incomes of $4,000 at 1 percent, which increased as income rose.

- c. As its governance was initially designed, members of the Federal Reserve Board served terms of only one year and were appointed by the president. The Secretary of the Treasury served as chairman of the board. The Comptroller of the Currency, an official who reported to the Treasury secretary, was also an ex officio member of the Board. Two factions formed within the board: (a) governors who were close to the Treasury Department, and (b) governors who reflected the concerns of the 12 reserve banks. The division within the board led to fraught policy making in the Fed’s early years.

- 1. “Plan for Banks of Issue,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 24, 1907, p. 1.

- 2. “France Feels Sure Our Crisis Is Over,” New York Times, November 24, 1907, p. C1. “Treasury to Allot $35,000,000 Threes; Crisis Considered Over,” New York Times, November 29, 1907, p. 7.

- 3. “Plan for Banks of Issue: Senator Hansbrough Believes Central Bank Should Be in Chicago,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 24, 1907, p. 2.

- 4. “Congress for Currency Law: Poll of Members by the Times,” New York Times, December 1, 1907, p. 1.

- 5. “Talk, Not Action, at This Congress: Imminence of Presidential Election Will Prevent Important Legislation at Washington,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 1, 1907, p. 1.

- 6. Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Henry White, November 27, 1907, in Morison, Blum, Chandler, and Rice (1952), pp. 858–859.

- 7. Report of the National Monetary Commission (1912), p. 6. Hereafter “NMC Report (1912).”

- 8. NMC Report (1912), p. 9.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. Ibid.

- 11. Ibid., p. 14.

- 12. McCulley (1992), p. 243.

- 13. Warburg (1930a), p. 12.

- 14. Details are from Glass (1927), pp. 124–126 and 173.

- 15. These points are summarized in Chandler (1958), pp. 34–40.

- 16. Bryan, quoted in Kazin (2006), p. 225.

- 17. Owen (1919), pp. 88–90.

- 18. As quoted from U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Banking and Currency, Subcommittee on Domestic Finance, 88th Congress, 2nd session, A Primer on Money, 1964 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office), p. 79.

- 19. Warburg (1930a), p. 4.

- 20. Indeed, the Fed monetized federal government deficits during World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War.

- 21. Quoted from the William McChesney Martin, Jr., Collection 1951 in Jessie Romero, “Treasury‐Fed Accord,” Federal Reserve History, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/treasury_fed_accord (accessed September 29, 2018).