Chapter 9

Nature versus nurture

Presenting is a skill, it is not a talent, a gift or a gene we are born with.

All too often when I run a course I meet individuals who assert to me that presenting is a talent or a gift rather than a skill like learning to play an instrument, drive a car or play a sport. ‘You either have it or you don’t!’ they tell me.

These individuals believe the great speakers of our time just stood up and spoke off the cuff dismissing the years of dedication, priority and preparation that has been put in. I assure them that if they were really speaking off the cuff they would certainly not be hailed as the great speakers of our time but rambling, unprepared generalists with no message or impact.

Great presenters are like great musicians or sports people – they work very hard and that is why they are the best.

What does it take to be a master presenter?

A study conducted by psychologist K. Anders Ericsson and two colleagues, with the help of professors at the Berlin Academy of Music, divided student violinists into three groups:

- Potential to be world-class soloists.

- Good, but unlikely to succeed professionally.

- Would become music teachers.

Each violinist was asked the same question, ‘Ever since you first picked up the violin, over the course of your entire career, how many hours have you practised?’

Everyone started playing the violin around five years old and during the first few years everyone practised on average two to three hours a week.

At age eight, the amount of practice changed for those who later became the best with the potential to be world-class soloists.

The ones who ended up with the potential to be the best increased their practice time from three hours a week to over 30 hours a week until the age of 20. By this time:

- These elite performers had each accumulated 10,000 hours of practice.

- The good violin students had totalled 8,000 hours.

- The future music teachers had totalled only 4,000 hours.

The same study was done comparing amateur pianists with professional pianists. The amateurs never practised more than three hours a week during childhood and by the age of 20 had totalled 2,000 hours. The professionals increased their practice over time until by the age of 20 they had reached 10,000 hours.

In Ericsson’s study there were no ‘naturals’, musicians who effortlessly floated to the top while practising less than others.

The research suggests that once a musician has enough ability to get into a music school, what distinguishes one performer from another is how hard he or she works. That’s it.

The people at the top don’t work harder or even much harder than everyone else. They work much, much harder.

The magic formula for presentation success

I was working with one of the world’s leading telecommunications companies over a number of years rolling out a series of six-month programmes designed purposefully to up-skill the entire management team and staff in the area of presenting with impact.

The six-month programme involved three distinct phases:

- Phase 1: Participants attend a two-day workshop on presentation skills.

- Phase 2: A one-day follow-up every month for four months involving one-to-one coaching.

- Phase 3: Long-term access to myself and my colleague regarding any specific presentation they are working on.

This was one of the most comprehensive programmes I have been involved in as a trainer. There was substantial investment by the company and a real aspiration to change the presentation culture in this organisation. Everyone on this programme presented as part of their job and had been handpicked by a manager to attend.

What was most interesting was the pattern that emerged over the time I did this work. Without exception participants from each six-month programme fell into one of three categories:

- The never-to-be-seen-againers

- There in body

- The devoted

The never-to-be-seen-againers

They came to the initial course but they didn’t prepare or overly engage. They never attended any of the follow-ups. They had no desire to be better presenters and were not willing to put any further work into their presentation skills.

No desire + no commitment = no change

There in body

These guys did attend the two-day course and most (but not all) of the follow-ups. They did have a very real desire to be better presenters, however they did not actually make the changes that were necessary. They turned up each month with the same development needs and despite being given the tools to up-skill they didn’t commit to changing their own behaviour. They did the same thing each month hoping for a better result.

Desire – commitment = no change

The devoted

These are the participants who got the results. They had the magic formula. They wanted to be better and they put in the work to achieve it. They took all feedback on board and used all the tools in this book consistently until they saw the change they wanted.

So what is the magic formula?

You have to want to be a great presenter and you have to consistently do the right things over and over again until you reach the required level of competence and confidence. It is as simple and as challenging as that.

Desire + commitment = presentation success

Presenting is a skill. You must have the desire to want to be a great presenter and the commitment to learn the skill.

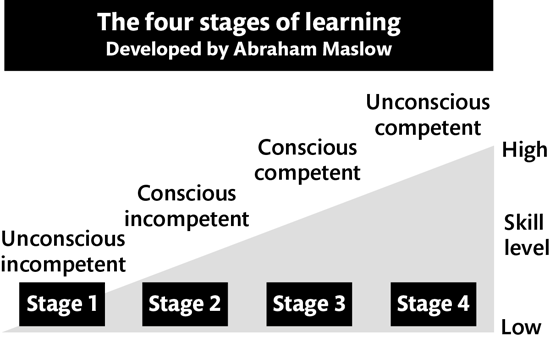

No matter what the skill, be it driving a car, playing a musical instrument or learning to present all human beings go through four stages.

The four stages of learning

The learning process is about making mistakes and learning from those mistakes. However, when we make mistakes as an adult learning to present we judge ourselves harshly for ‘not doing it right’, ‘not being good enough’, and we tell ourselves ‘that I can never learn this!’

Ironically, not doing it right and making mistakes as you learn to present are vital steps in the learning process to gain this great skill. To become a great presenter you have to go through the four stages of learning as uncovered by Abraham Maslow:

- Unconscious incompetence: ‘I don’t know that I don’t know how to do this.’ This is the stage of blissful ignorance before learning begins.

- Conscious incompetence: ‘I know that I don’t know how to do this.’ This is the most difficult stage, where learning begins, and where you will start judging yourself harshly. This is also the stage at which most people give up. Mistakes are integral to the learning process. They’re necessary because learning is essentially experimental and experience-based, trial and error. You can only learn by doing and making mistakes. What is very challenging about learning to present is that you are going through this phase in front of an audience that is judging you.

- Conscious competence: ‘I know I can do this, I am learning and it is showing.’ As you practise more and more you move into the third stage of learning: conscious competence. This feels better, but your presenting still isn’t going to be very smooth or fluid, at least not as much as you would like it to be. You will still have to think a lot about your behaviours.

- Unconscious competence: ‘I’m a natural!’ The final stage of learning a skill when it has become a natural part of us.

Source: Based on Maslow, A.H. (1943) ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’, Psychological Review 50(4), 370–96. This content is in the public domain.

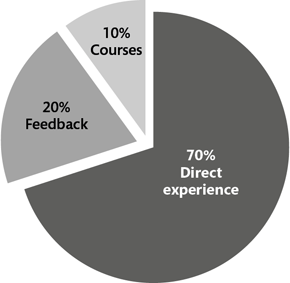

70/20/10

The 70/20/10 model is a learning and development model based on research by Michael M. Lombardo and Robert W. Eichinger. It states that:

- about 70 per cent of learning comes from direct experience of the skill;

- about 20 per cent of learning comes from feedback from mentors or managers;

- about 10 per cent of learning comes from courses and reading.

In order for you to develop great presentation skills you must remember these three elements:

- Present on the job (or wherever possible) on a regular basis.

- Receive feedback and coaching in line with any training you receive on a continual basis.

- Understand and gain the skill through attending courses and reading books.

If any of these elements are missing you will not be operating at 100 per cent of your potential.

Your challenge

The skill of presenting can only be gained by presenting. I understand that a difficulty for some of you reading this book is that you have limited opportunity to present in your jobs.

The only way you are going to be able to move through the four stages of learning is to find opportunities to present wherever and whenever you can, in your workplace, by attending a course or by joining a public speaking group in your area.

‘If nothing changes, nothing changes.’

Earnie Larsen

I keep having the same conversation

It could be a wedding, party (children’s or adult), networking event, lunch, breakfast … hell, any social gathering really and I somehow manage to always get myself into the same debate about my assertion that presenting is a skill that can be acquired.

I do, of course, appreciate and recognise that as with any skill some people take to it more easily than others. Some people enjoy it more than others. Some people want, need and desire to do it more than others.

Is it easier for some people to learn to present? Yes, of course. Do some people have talent? Yes. But talent is not a get out of jail free card. Talent is not a substitute or shortcut for hard work and dedication. If you look at any successful person at the top of their field, even with talent they still work very, very, very hard.