Chapter 11. Facilitating Research

In a high-IQ job pool, soft skills like discipline, drive, and empathy mark those who emerge as outstanding.

—Daniel Goleman

The most unpredictable part of research, especially qualitative research, is people. Carrying on a conversation with a complete stranger while actively listening doesn’t come easy. The skills needed to perform this are known as facilitation. Despite many books sharing techniques, the best way to learn facilitation skills is through trial and error. The goal of this chapter is to equip you with the basics to ease your learning in the field.

Soft Skills Are Hard

Some of the most important skills needed to be a successful researcher aren’t taught in the classroom. These are soft skills, since they relate to social and interpersonal aspects instead of workflow or tasks. While degree programs and vocational institutions are great at teaching students how to program computers, engineer machines, and recode genetic material, they often fail at teaching the skills needed to hold a conversation or connect with another human being—whether that means introducing yourself at networking events or giving formal presentations to a group.

These skills aren’t taught because, to be frank, they are hard to teach and even harder to learn. There’s a lot of trial and error involved in picking up soft skills, and an ongoing feeling of failure doesn’t interest a lot of students.

What Are Soft Skills?

Before we get deeper into the skills needed to become a good facilitator, let’s frame the term soft skills. It’s common to relate a person’s proficiency with soft skills to their EQ, or emotional quotient. EQ has emerged as a tool to describe how one uses their soft skills.[4] The higher your EQ, the more natural it is for you to pick up the skills needed to facilitate qualitative research. Similarly, with a higher EQ you’ll find it easier to connect with stakeholders when providing guidance and recommendations based on your quantitative research results.

Common skills that facilitators pick up include social graces, communicating effectively, managing and leading people, noticing different personality traits, and responding to these traits. When you consider the mental and emotional juggling it takes to get these skills right, it’s apparent why they aren’t taught before students enter the professional world. Still, these skills not only make great researchers, but help individuals grow in their careers.

Why Soft Skills Matter

Why are soft skills important to becoming a researcher? One of the major points of doing any form of research, qualitative or quantitative, is to create an empathetic link with your users. As you hone your EQ levels, you can better connect with users. You can learn about their successes, failures, joys, and pains. The act of facilitating requires this connection so participants feel that you are listening to their stories and genuinely care about them.

Soft Skills Can Be Learned

At this point you might be thinking, “Whoa! If a class can’t do it, how can a book teach me soft skills so I can successfully start doing research?” Fear not! We ourselves are proof that these skills can be learned. We were once more comfortable on the sidelines, while those more experienced led research activities and client interactions. Eventually, we were put in the driver’s seat and figured it out.

The biggest barrier to learning soft skills is the ability to practice them. As the old adage goes, “practice makes perfect.”

Mastery Through Practice

While there are many factors to learning and mastering soft skills, the best teacher is practice. You can practice with friends and family through mock interviews. You can learn on the job by working under a lead researcher and inviting critique on your facilitation skills.

The rest of the chapter focuses on two core aspects of facilitation that enable learning: body language and microexpressions.

Body Language

Humans are expressive creatures. When having a conversation, we say way more with our body and facial expressions than we do with our words. Our physical reactions to what’s being said to us, and how we use our body to emphasize what we are saying, makes talking with people entertaining. By becoming aware of both our own body language and that of others, you gain insight into the other soft skills mentioned earlier in the chapter.

What Is Body Language?

Body language includes the different signals and cues our body gives off, some voluntary but many involuntary. These signals are paired with what we are trying to communicate. A classic example is someone throwing their arms up and waving them around when excited. You could be standing 50 feet away, and just by observing their body you know they are excited about something.

Body language is tricky because it’s a mix of different signals that can mean different things depending on context, culture, and how the signals match up. As you master the art of reading body language, you’ll learn to pick out different patterns and, based on the context, figure out what the most likely message is. However, even the best body language experts get it wrong sometimes and, rest assured, you will too.

Why Body Language Matters

When you’re facilitating qualitative research, the feedback you collect includes verbal responses, physical reactions to the questions asked, and physical behavior toward the product itself. These reactions are moments you want, because they’re the perfect opportunity to learn more. If you see someone make a face like they’ve smelled spoiled milk (Figure 11-1) or they physically back away from your product, something has occurred that their subconscious has interpreted as offensive. This is your chance to ask what they are thinking and why they are reacting so negatively.

Without picking up on a participant’s body language, you might miss a piece of evidence on why something is wrong with your product and how you could make it better.

How to Use Body Language

As you progress in reading body language, you’ll want to use it more proactively than rote observation. This shift from reactive to proactive facilitation separates junior and senior researchers.

Participants’ body language

Regardless of our emotional state, our brains react to our environment with one common element: they are constantly filtering data received through our five senses. Whether we’re searching for pleasure or safety, the data collected in our brain causes involuntary reactions.

When facilitating research, you need to look for these reactions to further understand people’s real feelings. Body language is often more honest than what participants tell you. Participants are known to express experiences more positively than they actually perceived them so that they don’t feel like a failure or feel uncomfortable giving you a negative critique to your face.

Your body language

Most researchers agree it is difficult to stay focused during every session, especially when scheduling many days of work. Being aware of your own body language is just as important as interpreting that of your participants. In this way, you prevent your fatigue from influencing participants.

To mitigate this, be aware of how you present yourself and ensure you’re perceived as open and receptive. Common tricks include constant note taking, leaning in during interesting moments, and keeping your arms and shoulders open so you appear welcoming.

Mirroring

Occasionally, you get a difficult participant. Not a dud, as discussed in Chapter 7, but rather someone who holds back information and doesn’t seem to trust you enough to open up. One technique to overcome this is mirroring. Mirroring is when one person’s body language is imitated or reflected by the other person (Figure 11-2). Strangely, this is very natural among people. Next time you’re talking with someone over coffee, pause and look at how you are both holding yourselves. You might be surprised to find aspects of your body language resemble that of the other person.

Mirroring can be used proactively to a certain extent, since it’s a natural reaction. When facilitating a session with a difficult participant, purposely mirror their body language. As the session progresses, shift to more open body language and see if the participant does the same. Physical stances can directly impact our mental state, and if you get the participant to mirror your open physical positions, they are more likely to be more open with their feedback.

Key Body Signals

The following are several classic signals that hint at another person’s mental state (see Figure 11-3). We want to caution you against fixating on a single signal and drawing conclusions from it, however. It’s important to take into account all signals observed in the context of the conversation.

- Open arms and legs

Oftentimes, when your body is in an open position, your mindset is also open. This can mean when you are presented with ideas, you might be more approachable and agreeable overall.

- Closed arms and legs

The opposite is true if your body is in a closed position. It’s likely that your mindset is defensive and potentially closed off.

- Spread-out arms and legs

Everyone has their own personal bubble, and sometimes stretching out your arms and taking a wide stance reflects an attempt to expand your personal space or assert your overall presence.

- Leg positioning

Your legs like to point in the direction you want to move. For example, if your legs are crossed and pointed at the door, there’s a chance that you may not want to be wherever you are.

- Head movements

When you look up it can indicate that you’re accessing your imagination and potentially being deceitful. When you look down it can indicate that you’re accessing your memory and potentially being more truthful.

Microexpressions

Your body isn’t the only thing communicating signals; facial expressions also add to nonverbal communication. Microexpressions are the subtle ways your face reacts, sometimes voluntary and other times not. One example is the natural crow’s feet that appear around your eyes when you smile (see Figure 11-4). If it is a genuine smile, those muscles around the eye contract involuntarily.

There are many different kinds of microexpressions, and entire courses of study about this mode of communication. Knowing they exist and how to use them in the context of research gives you another advantage when you’re conducting research in person.[5]

Why Microexpressions Matter

Not everyone acts naturally during research sessions. That’s because research is unnatural in the first place, and people might feel obligated to tell or show you what they think you want to hear. By watching a participant’s microexpressions and body language, you can redirect or follow up with probing questions to better understand how they really use or feel about your product.

How to Use Microexpressions

The best way to use microexpressions is to couple observation skills with active listening skills. When trying to understand how someone uses your product, pay attention to both their words and their physical reactions. You will see hints of truth, deceit, and reservation that inform your probing and follow-up questions. Actively observing in this way means you are less likely to miss anything worth capturing.

Your own microexpressions play a part too, because the participant’s subconscious is watching you. After a number of sessions, you will need to ensure you aren’t falsely representing your level of interest. This is why, in Chapter 6, we shared methods for managing energy levels. If you are tapped out and “phoning in” a session, your body language and microexpressions will give you away, regardless of how well you think you are feigning interest.

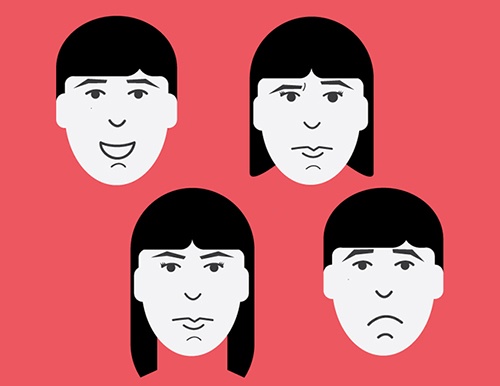

Key Expressions

There are a number of common microexpressions that you should actively look for, as cross-cultural studies have shown that, although the interpretation of expressions is universal, the expression of emotions through the face changes depending on social context.[6] The expressions on this list are generic enough that just about everyone does them and, if you pay attention, you will be able to better predict when you should probe deeper or just move on to the next line of questioning (see Figure 11-5).

- Surprise

Eyes open wide and jaw dropped. Something has happened that the participant didn’t expect and you should try to learn what it was, why it surprised them, and what they were expecting.

- Fear

Eyes wide, mouth barely open, and forehead winkled. The participant might feel like they made a mistake and have failed in some way. You will want to know why they are feeling this way and how to ease this feeling.

- Disgust

Teeth bared, nose wrinkled, and eyes slightly closed. Whatever the participant was saying or doing does not agree with them and they feel “offended.” Get to the heart of this offense and try to learn why they feel this way.

- Anger

Hard stare, closed and tense lips, and nostrils possibly open wide. Something has made the participant go on the defensive. Try to understand what is causing this reaction and why it happened.

- Happiness

Broad smile, crow’s feet around the eyes, and raised cheeks. The product or topic on hand clearly is one that makes the participant feel good. Probe into why they feel so happy about what’s happening and try to probe the triggers of this response.

- Sadness

Pouting lips and drawn-in eyes. An action or conversation has triggered the participant to feel bad. You will want to understand what the trigger was and how it might have been avoided.

- Contempt

Partial fake smile and squinting eyes. The participant doesn’t trust what just happened or whatever you have just said. Probe into where this distrust is coming from and how it’s affecting the participant.

Cultural Implications

If working on a product that has a global presence, you will encounter situations where nonverbal cues from one culture don’t apply to another. Something as simple as the thumbs up to show that everything is OK in one culture might be an offensive symbol that can ruin a research session in another. Fear not: there are steps you can follow to navigate these murky waters and avoid awkward situations.

Do Your Homework

First, research different social norms and the background of any country you’ll be conducting research in. What documentation from other researchers can you use to prepare? You’ll want to research topics including how authority is perceived, how gender roles differ, how foreigners are viewed, and what topics or gestures are a sign of respect or disrespect.

One of the best places to learn about local customs and social norms are tourism sites. This content has been curated for years to ensure visitors have all the information they need to enjoy their trip and avoid negative experiences with locals.

Come from a Place of Respect

Research aside, approach everyone from a place of respect. If appropriate, be ready to apologize quickly and often as you stumble through a session. Because the context of your visit is to conduct research, there is a degree of forgiveness allowed by those you encounter when mistakes are made.

Exercise: Reading Nonverbal Communication

Reading nonverbal communication is hard to practice, as it typically requires other people. There are a few methods you can work through, however, to refine your skills.

Mimicry

Actors are masters at performing with both their words and their bodies. Pick a favorite movie and mimic the actions and expressions that are happening on screen during the dramatic moments of the film. Try to learn the different combinations of movements and facial expressions that the actors use to act out the scene, as these will be the same combinations and expressions you’ll observe in the real world.

Observation

Many researchers claim people watching as a favorite hobby. Put this hobby to use by watching how people react to each other in public spaces, or how they react when having a conversation. Try to pick up on the different emotions that are being expressed and see what kind of reactions they get. The best place to do this kind of practice is in public spaces, like a shopping mall, coffee shop, or an airport.

Inquiry

If you want to get some direct critique on your new observation skills, ask a close friend for help. Start with a normal conversation. Look for certain nonverbal cues and ask your friend what they are feeling or thinking. Occasionally, guess their thoughts or feelings and ask if you’re right or wrong. This can be a bit awkward, but it’s one of the only times you’ll get candid feedback on how well your observation skills are progressing.

Parting Thoughts

The best way to learn and grow facilitation skills is through practice. When you start practicing, you will make mistakes. Each mistake teaches you valuable lessons and hones your skills.

The biggest hurdle for one of the authors was overcoming social awkwardness. Sitting down and talking with strangers was terrifying. Over time, however, he found his groove and is now less of a nervous wreck. Running research activities, especially qualitative ones, gets easier with time. Keep at it and don’t let the little mistakes that only you notice stop you. Once you have the research under your belt, the real fun begins—sharing with your team and organizing your findings!

[4] Claudia S. P. Fernandez, “Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 13, no. 1 (2007): 80–82.

[5] To learn more about the importance of microexpressions, listen to “Microexpressions: More Than Meets The Eye,” a 2013 NPR interview with law enforcement officer David Matsumoto (http://www.npr.org/2013/05/10/182861380/microexpressions-more-than-meets-the-eye).

[6] Vinay Bettadapura, “Face Expression Recognition and Analysis: The State of the Art,” arXiv (March 2012).