16 Financial and Accounting Considerations for Broadcast and Cable Acquisitions

The business you started in your garage a few years ago has been astonishingly successful! So much so that you attracted the attention of the major players in your field. One makes you an offer you can’t refuse, and you’ve just pocketed a check for several million dollars. What to do with all that capital? You don’t want to give it to Uncle Sam. You look around and think it would be nice to be in the broadcasting or cable field. John S. Sanders—a founding principal in Bond & Pecaro, Inc, a Washington, D.C.–based consulting firm specializing in providing financial, economic, and valuation services, including fair market valuations and purchase price allocation reports to media and communications companies—will walk you down that often slippery slope of acquisitions.

Introduction

In recent years, the financial and accounting aspects of completing a broadcast or cable acquisition have become increasingly complex. This complexity has been driven by two primary factors.

The first is greater economic and competitive pressure on the broadcast and cable industries, which has altered dramatically the environment for media companies. Historically, television and radio businesses were characterized by stable growth rates and profit margins, but they are now adapting to a more volatile environment defined by competition from the Internet, cable, and satellite services, and from portable listening devices, such as iPods. Slowing advertising growth and increasing cyclicality due to political advertising have also affected the industry.

The cable industry has also changed dramatically. What had originally been a business focused on providing one-way video content has evolved into a diversified telecommunications provider offering a “triple play” of video, Internet, and telephone services—or even a “quadruple play” that includes cellular phone service. The confluence of these economic factors has made the valuation process more complex.

The second factor that has influenced the acquisition process is the increasing financial scrutiny that has resulted since the implementation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and related accounting standards such as Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (FAS) Nos. 141, 142, 144, and 157. (See .) These measures were implemented in the wake of high-profile financial scandals at Enron, Tyco, Adelphia, WorldCom, and other companies. The measures impose strict standards on how companies report the value of acquired assets and liabilities and, on an ongoing basis, how they convey information to investors about the validity of those values. Moreover, auditors are now devoting greater resources to reviewing and analyzing the financial accounting associated with an acquisition.

This is a brief overview of the financial and accounting considerations in a broadcast or cable acquisition. It is not intended to be an in-depth treatise or a step-by-step guide to accounting for a transaction. Each transaction will have its own unique characteristics; experienced buyers of media properties know that one of their best investments when going through the process is hiring someone who handles these types of transactions for a living.

The areas to be covered include determining the value of a property, due diligence considerations, purchase price allocations, and accounting requirements.

Determination of Value

The process of determining the value of a broadcasting or cable television property is highly specialized, although certain techniques are generic. The primary methods employed are the income approach, which involves forecasting the revenues and profits attributable to a broadcasting or cable business, and the market approach,1 which involves analyzing sales of similar businesses and, if appropriate, the behavior of publicly traded media stocks.

In order to determine the fair value of a broadcasting or cable business, projections of discounted cash flow are developed by professional appraisers or by the in-house staff of media companies. The income approach measures the economic benefits the business can reasonably be expected to generate. The fair value of the assets of a cable or broadcasting business may be expressed by discounting these expected future benefits.

Other commonly used valuation methods include the cost approach. For a number of reasons, the cost approach is often not suitable to the valuation of an ongoing broadcasting or cable business because most of their assets are intangible. The principal assets of these businesses are FCC licenses, in the case of broadcasters, and cable franchises, in the case of cable companies. Comparable FCC licenses and franchises cannot be obtained at an identifiable cost. The FCC controls the licensing process, and municipalities have traditionally controlled the cable franchising process; as such, there is no significant marketplace in which similar licenses or franchises can be purchased. Cable franchises were originally granted through a competitive process based on service offerings, and cannot be bought or sold apart from an ongoing business. Consistent with the paradigm of lower of cost or market, the cost approach may be applicable in the case of certain specific assets.

However, the market approach is useful in the valuation of broadcasting and cable businesses. Using marketplace transactions, sales of broadcast stations and cable systems can be expressed as multiples of operating cash flow, which facilitates the comparison of stations or systems of different sizes or in different markets.

Television and radio businesses have typically changed hands at multiples of between 10 and 17 times current operating cash flow, depending upon growth potential, market size, interest rates, and other characteristics. Cable values are expressed as both multiples of cash flow and multiples of subscribers. The average value of cable systems increased from approximately $2,000 per subscriber in the early 1990s to over $5,000 in the early 2000s as investors became attracted to the growth potential of telephony and Internet services. Values have now settled back into the $3,000- to $4,000-per-subscriber range.

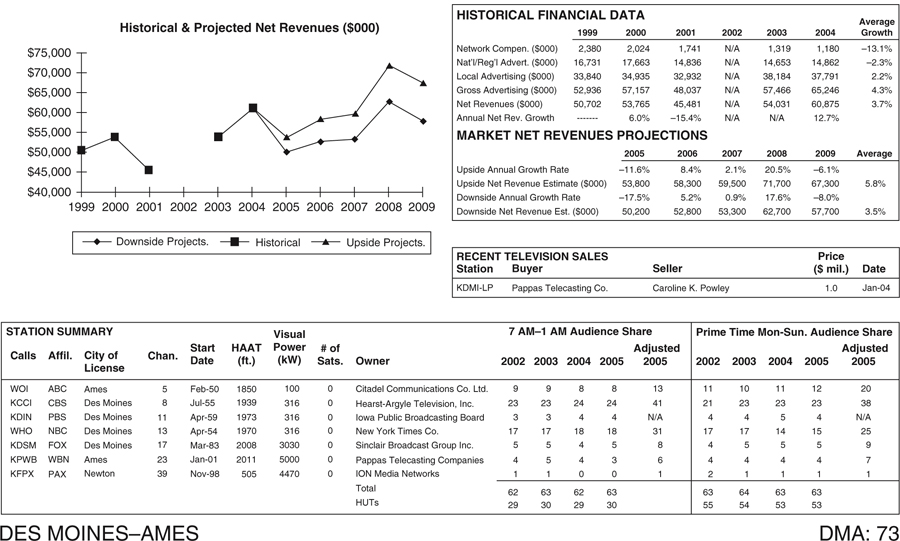

A thorough valuation begins with an analysis of the market in which a station or system operates. Figure 16.1 contains a sample page from The Television Industry: A Market-by-Market Review (National Association of Broadcasters/Bond & Pecaro, Inc.). This reference book and others like it provide information on important variables such as population and income growth, competition, market share, total market revenues, comparable transactions, and the like. These variables form the initial inputs used to develop the discounted cash flow model, and can also affect assumptions regarding future growth rates and similar factors.

FIGURE 16.1 Sample Market Profile.

The discounted cash flow models used in broadcasting appraisals incorporate variables such as market revenues, revenue-share projections, operating expenses, profit margins, capital expenditures, and various discount rates. In the cable industry, important variables include subscriber growth rates, revenues per subscriber for different services, and churn (percentage of subscribers who disconnect cable service during a specified period).

A discounted cash flow projection period of five to ten years is often determined to be an appropriate time horizon for the analysis. Broadcast stations and cable system investors typically expect to recover their investments within a five- to tenyear period. It is during this time frame that projections regarding revenues, market share, and operating expenses can be made with a degree of accuracy.

The process essentially involves developing a picture of the financial future of a business, with projections of each important variable: market revenues, station or system revenues, operating expenses, income taxes, capital expenditures, and the like. Proper consideration of tax implications is particularly important because, as will be explained below, businesses that rely primarily on large intangible assets enjoy significant tax benefits.

Federal and state income taxes are deducted from projected operating profits to determine after-tax net income. Depreciation and amortization are also added back to the after-tax income stream, and projected capital expenditures and, if appropriate, working capital adjustments are subtracted to calculate a business’s net after-tax cash flow.

The stream of annual cash flows is adjusted to present value using a discount rate appropriate for the business. The discount rate used is typically based upon an after-tax rate calculated for the industry. This rate can be derived from information about the stock prices and debt characteristics of industry peers and likely acquiring companies.

Additionally, it is necessary to project the broadcast station’s or cable system’s terminal value. Two methods are often used in this calculation. An operating cash flow multiple can be applied to a station or system’s operating cash flow at the end of the projection period, and then adjustments can be made for capital gains taxes and other expenses to yield the actual proceeds that will accrue to the owner of the station or cable system. Alternatively, an annuity method, also known as the Gordon Growth Model or the perpetuity method, can be used. This entails dividing an estimate of free cash flow, also referred to as net after-tax cash flow, at the end of the forecast period by a capitalization rate. The terminal value represents the hypothetical value of the business at the end of the projection period. The terminal value is then discounted to present value at an appropriate discount rate.

Case Study

Table 16.1 contains an example of a discounted cash flow forecast for a hypothetical television station, WUVW, in a Top 50 market with total market television revenues of just over $100 million.

Several characteristics are noteworthy about the projection in Table 16.1—some of which reflect changes that a likely buyer would implement in the financial performance of the station, and some of which relate to regulatory and tax factors:

1. In this case, the station is seen to have the potential to increase its share of market revenues to 6 percent from 5.2 percent. Typically, this judgment is based upon the performance of similar stations in other markets or the station’s actual audience performance. Parameters used in these comparisons include channel position, coverage area, competition, the number and type of television signals (i.e., UHF vs. VHF) in a market, likely network affiliation, and the demographics of the market.

2. There is also an expectation that the operating cash flow can be improved to 27.6 percent from 23.8 percent. The “mature” margin is typically based upon an industry norm derived from analyst reports or from surveys conducted by third-party entities such as the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) and the Broadcast Cable Financial Management Association (BCFM).

3. It is noteworthy that taxable income is significantly less than operating cash flow for most of the projection period, and that no income taxes are payable until well into the forecast period. This is due to the impact of Section 167 of the Internal Revenue Code. Section 167 permits intangible assets, which account for most of the value of a television or cable business, to be written off against income on a straight-line basis over a 15-year period. (More on this in the discussion of purchase price allocations below.)

4. In each year, the free cash flow is discounted to present value, in this case at a discount rate of 8 percent. For example, the $1,412,000 to be received in Year 3 of the forecast has a present value of only $1,165,000 in today’s dollars. In total, the year-to-year after-tax cash flows have a present value of $10,440,600.

As discussed earlier, the investor still owns the broadcast station or cable system at the end of the projection period. In this case, as indicated in Table 16.2, the terminal value was calculated to be $23.8 million. Complex calculations go into the projection of this amount. In this case, the terminal value is equivalent to about 8 times Year 10 operating cash flow and 14 times Year 10 free cash flow. The present value of the terminal value is $11.0 million. When this amount is added to the present value of the cumulative cash flows and a provision for the amortization remaining at the end of the forecast period, a total value of $22,468,000 for the station is indicated.

TABLE 16.1 Projected Sample Television WUVW Operating Performance (Dollar Amounts Shown in Thousands)

1 Taxable income is computed as operating cash flow less depreciation and amortization.

2 Net after-tax cash flow is calculated as after-tax income plus depreciation and amortization less capital expenditures and changes in working capital.

TABLE 16.2 Valuation of Sample Television WUVW (Income Method) (Dollar Amounts Shown in Thousands)

| Future Terminal Value in Year 10 | $23,811.2 |

| Discounted Terminal Value @ 8.0%2 | $11,029.2 |

| Total Present Value Cash Flow1 | 10,440.6 |

| Plus: Present Value Tax Benefit of Remaining Amortization | 997.7 |

| Fair Market Value Sample Television Station WUVW | $22,467.5 |

1 The terminal value is typically calculated through a multiple of operating cash flow or free cash flow, with appropriate adjustments for depreciation and amortization, capital expenditures, working capital, and income taxes.

2 See text.

Bringing the whole analysis back to today’s terms, the value of approximately $22.5 million is equivalent to a multiple of approximately 17 times the $1.7 million of operating cash flow in the first year of the forecast. This amount might seem high relative to the average range of 10 to 14 times, but is consistent with the “upside” growth potential resulting from increasing the revenue share and expanding the operating margin.

The employment of cash flow multiples is a common application of the market approach in the broadcasting and cable industries. Multiples may be less useful, however, in “turnaround” situations when a station or system is underperforming, or if it is overperforming. In other words, a discounted cash flow may yield a value outside the range indicated by “average” income multiples. The analyst should scrutinize the assumptions that underlie the discounted cash flow analysis to determine whether the variance is justified, or whether inputs to the model should be reconsidered. In the case of our example, the indicated value fell above the range, but this appeared to be justified by opportunities to dramatically increase cash flows.

The $22.5 million is the value of the operating assets of the business. This is the most typical configuration for a media acquisition because it is the cleanest. Often, however, the purchaser will acquire the stock of the entity that owns those assets, rather than the assets of the business directly. For example, if BCFM Broadcasting, Inc. acquires Television Station WUVW in an asset purchase from UVW Holdings LLC, it is purchasing only WUVW’s equipment, studios, FCC licenses, contracts, and related assets. UVW Holdings would still be owned by its stockholders, just without the operating tangible and intangible assets of WUVW.

In a stock transaction, BCFM Broadcasting, Inc. acquires UVW Holdings as a company, and gets more than just the WUVW operating assets. It typically assumes UVW Holding’s debt and other “nonoperating” assets and liabilities, such as cash, accounts receivable and payable, deferred taxes, and the like. Also assumed are any potential lawsuits or claims (tax, environmental, employment, or other claims, both known and unknown) that may be brought against UVW Holdings. The risk related to such contingent liabilities is one of the reasons buyers typically prefer an asset transaction or generally pay a reduced purchase price for a stock transaction.

To arrive at a stock value, the value of the operating assets needs to be adjusted for those other assets and liabilities. Using the example above, the value of UVW Holding’s equity is as follows, assuming its only operating asset is Television Station WUVW, and the only other relevant balance sheet items are $6,000,000 in debt and $1,500,000 in cash.

| Station Value | $22,500,000 |

| Plus: | Cash 1,500,000 |

| Less: Assumed Debt | (6,000,000) |

| Equals: WUVW 100 percent Equity Value | $18,000,000 |

Interestingly, however, although asset purchases are typically preferred by the buyer, the formulation of a purchase agreement in an asset transaction may be more burdensome than in a stock deal. This is due largely to the need to carefully itemize the tangible and intangible items that convey, and those that do not.

Due Diligence Considerations

The process of due diligence usually takes place between the signing of a letter of intent for a transaction, the formulation of a purchase agreement, and the actual closing of the transaction. Many of these factors are generic, but others, particularly those that relate to FCC licenses and cable franchises, are unique to these industries. The process of due diligence is typically conducted in conjunction with qualified legal, accounting, and appraisal professionals, and is intended to avoid potentially damaging discoveries after the closing has taken place.

The primary components of due diligences include confirming the accuracy of information and compliance with laws and regulations in areas including:

1. Organizational Standing—Particularly if stock is being acquired, making sure that the company is properly and legally organized and incorporated, that the necessary documents are in order, and that necessary fees and taxes are up-to-date.

2. Licenses and Franchises—FCC licenses and cable franchises are subject to unique requirements, and it is critical that they be in conformity with FCC and municipal requirements.

3. Financial Statement Review—Because the acquirer of a cable or broadcasting business is acquiring a stream of income (hence the prevalence of cash flow multiples in valuation), it is critical that financial statements be analyzed and verified.

4. Real Property—Owned realty needs to be properly titled, and copies of all related titles, deeds, mortgages, and the like should be provided. Documentation also needs to be provided—and, in some cases, testing conducted—to ensure that the properties are in compliance with all environmental regulations.

5. Tangible Assets—A detailed inventory of acquired assets should be provided and confirmed. In some cases, the acquirer will conduct a detailed fixed asset inventory.

6. Intellectual PropertyandOtherIntangible Assets—Particularly important intangible assets at a broadcasting business include programming agreements, talent and management contracts, facilities leases, income leases, and advertisingrelated assets. Key cable system intangibles may include supplier agreements, programming agreements, multiple dwelling unit (MDU) contracts, and the acquired base of subscribers. These also need to be validated and documented.

7. Stock Transaction Due Diligence—The due diligence requirements of a stock transaction are generally more important and complex than in an asset transaction because the buyer is in essence stepping into the seller’s corporate shoes and assuming responsibility for more known and possibly unexpected claims related to agreements with prior employees, customers, vendors, benefit plans, and the like.

Due diligence procedures also include identification of going-forward operational strategies such as which contracts will be assumed and which will need to be renegotiated. Other considerations include a staffing assessment, evaluation of talent and news strategies, market research, and consolidation opportunities.

Purchase Price Allocations

Once the total value of a transaction is determined and commitment to the transaction is made by a purchase agreement, it is necessary to embark upon a second type of valuation analysis: the purchase price allocation.

For financial reporting and tax purposes, it is necessary to allocate the total value to different classes of tangible and intangible assets. The treatment of these assets can be quite different for tax and financial reporting purposes. For example, FCC licenses and cable franchises are treated as Section 197 intangible assets, almost all of which are written off over a 15-year life for tax purposes. For accounting purposes, however, they are treated as “indefinite-lived” intangible assets, which simply remain on the balance sheet at their acquisition cost unless a triggering event occurs that causes the value to decline below the acquisition cost, at which time a revaluation of the assets in conformity with FAS 142 (accounting for goodwill and other intangible assets) is conducted.

Typically, the tangible assets in a broadcasting or cable acquisition account for a relatively small portion of the purchase price. The more important assets are the FCC licenses, in the case of a television or radio station, and the franchise agreements, in the case of a cable system.

An inventory of the tangible property is typically conducted in order to ensure that items are properly categorized and documented. Between 20 and 30 tangible asset categories may be involved in a broadcast or cable acquisition, such as land, land improvements, leasehold improvements, buildings, technical equipment, antenna equipment, headend equipment, converters, transmitter equipment, microwave equipment, vehicles, and the like. These assets are usually appraised on the basis of the depreciated replacement cost. Items for which an active used-equipment market exists—such as furniture, office machines, and tools—can also be appraised using a market-sales or comparable-sales approach.

Intangible assets, depending upon the asset in question, can be valued using the income, cost, market, or residual approaches.

A simple purchase price allocation example for a radio station and a cable television system appear in Table 16.3.

TABLE 16.3 Examples of Purchase Price Allocation

Accounting Requirements

Several standards promulgated in recent years by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) place requirements on when and how asset values are recorded. It should be borne in mind that these standards are different from the prevailing tax regulations. These current standards are summarized in the sections that follow.

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 141: Business Combinations

Under FAS 141, all business combinations are to be accounted for using the purchase method of accounting. Previously, the pooling-of-interests method, which essentially consisted of adding together the balance sheet of the merging entities, was also acceptable.

Where it exists, goodwill, defined as the excess of the cost of an acquired entity over the net of the amounts assigned to acquired assets and assumed liabilities, is to be recognized. Other acquired intangible assets are to be separately recognized if: (1) they arise from contractual or other legal rights, regardless of whether those rights are transferable or separable from the acquired enterprise; or (2) in cases where they do not arise from such contractual or legal rights, only if they are separable—that is, capable of being separated or divided from the acquired enterprise.

The pronouncement contains a long list of intangible assets that need to be considered, which adds a layer of complexity to the acquisition accounting process. For example, it does not appear to be permissible to appraise a single asset that covers the business’s base of customers. This should be broken out between the customer list, customer contracts, and customer relationships.

A lengthy list of illustrative intangibles that are deemed to be distinguishable from goodwill has been compiled by the FASB. Among the listed intangible assets used by broadcasting and cable businesses are trademarks; trade names; noncompetition agreements; customer lists; customer and supplier relationships; video, audio, and music materials; licensing and royalty agreements; advertising contracts; lease agreements; franchise agreements; operating and broadcast rights; employment contracts; and Internet domain names. Statement 141 specifically provides that the value of an assembled workforce of at-will employees acquired in a business combination is to be included with goodwill.

When reporting a business combination, notes to the financial statements must disclose specific information where it is significant. For intangible assets subject to amortization: (1) the total amount assigned and the amounts assigned to major intangible assets, (2) the residual value, and (3) the weighted average amortization period by major intangible asset class.

Similarly, for intangible assets without a determinable life: (1) the total amount assigned, and (2) the amount assigned to any major intangible asset class.

In the case of goodwill: (1) the total amount of acquired goodwill, (2) the amount that is expected to be deductible for tax purposes, and (3) the amount of goodwill by reporting segment.

The definition of a reporting segment was the subject of considerable debate when FAS 141 was implemented. For example, a radio group might own 100 individual AM and FM stations licensed to 30 markets, grouped into three regions. This raised the question as to whether a “reporting unit” should be each station, a market cluster, or an entire region. Consistent with the way their stations are organized and report their results, many broadcasters group the properties by market cluster, as opposed to individual call letters, on one hand, or by broad regions, on the other. Cable businesses tend to be divided into rational regional definitions.

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 142: Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets

FAS 142 deals with how intangible assets are treated after the acquisition has occurred. Intangible assets with determinable lives are written off over their respective lives.

FAS 142 requires that intangible assets without determinable lives, which include FCC licenses and cable franchises, be reviewed for impairment. This “testing” needs to occur annually, or more frequently if there is a triggering event such as a bankruptcy or pending divestiture.

A recognized intangible asset should be amortized over its anticipated useful life. Such amortization must reflect any anticipated residual value associated with the asset. By contrast, an intangible asset with an indefinite useful life should not be amortized until its life can be determined. Both types of intangible assets must be tested for impairment annually, or more frequently in cases where impairment may have occurred.

Regarding these assets, the appropriate tests differ. For assets with determinable lives, the sum of the undiscounted cash flows over the remaining life of the asset is compared to the carrying value, in accordance with Statement 144; this is often referred to as a recoverability test (see below). If the sum of the undiscounted cash flows does not exceed the carrying value, impairment exists and the fair value must be determined, with a loss equaling the difference between the fair value and the carrying amount recognized. For intangible assets without determinable lives (those that are not subject to amortization), the test consists of comparing the fair value of the asset to its carrying value. Where necessary, an impairment loss equal to the difference must be recognized.

Finally, Statement 142 states that if goodwill and another asset of a reporting unit are tested for impairment at the same time, the other asset shall be tested for impairment before goodwill. If the other asset is impaired, the impairment loss would be recognized prior to goodwill’s being tested for impairment.

A noteworthy aspect of FAS 142 is that a company must book impairment if an asset or a reporting unit declines in value. However, there is no corresponding mechanism to book an increase in value over the cost basis if an asset appreciates.

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 144: Accounting for the Impairment of Long-Lived Assets

Long-lived assets typically include assets held for use such as land, buildings, equipment, natural resources, and various intangible assets. Long-lived assets in the broadcasting and cable industries may include customer relationships, leases, long-term facilities contracts, and the like. Assets such as FCC licenses and cable franchises are assets with indefinite lives.

Typically, a long-lived asset is depreciated over time, and is tested for impairment only if there is a triggering event, such as a dramatic decline in the market overall, poor performance of the asset, or the expectation that the asset will be sold.

Interestingly, the impairment test compares an asset’s undiscounted future cash flows with the carrying value. If the asset fails the test, then the measurement of the impairment reverts to the difference between the fair value and the carrying value.

Case Study

So, for example, a five-year contract with a key news personality may have been acquired with a television station and given a carrying value of $250,000 with expected amortization over a fiveyear period. At the end of Year 2, the carrying value is $150,000, assuming a simple straight-line amortization schedule. Assume further that the particular news broadcast shows a steep drop in ratings accompanied by a decline in advertising revenues. If a revised financial analysis shows that the incremental undiscounted cash flow attributable to the news personality is greater than $150,000, no impairment would be indicated. However, if the sum of the undiscounted cash flows is less than $150,000, impairment is indicated. In order to measure the impairment, however, the carrying value must be compared to the asset’s fair value, which might be measured by a discounted cash flow analysis or perhaps an analysis of comparable talent contracts. If this exercise indicated that the fair value was $50,000, then an impairment charge would result in a $100,000 reduction in income, and an accompanying reduction of $100,000 in the carrying value of the talent contract.

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 157: Fair Value Measurements

FAS 157 endeavors to provide a new and more consistent definition of fair value, which is as follows:

Fair value is the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

This definition contains a slight but significant variation in the traditional definition for fair market value, as well as the definition of “fair value” that was originally articulated in FAS 142. This distinction has to do with the phrase “market participant.” The phrase implies that the acquirer would be a typical buyer, not a particular buyer. In most cases, this would be a diversified media, broadcasting, or cable company. What is important is that fair value in this case may not be the absolute highest value that might be paid, for example, by the one company for which an asset has the highest value. In some cases, it may be difficult to justify a purchase price made for strategic reasons because of the lack of similar transactions to support fair value. Then, because annual evaluations are required based on the operating results, some intangible assets could be subject to an impairment charge shortly after the transaction because of the limited operational benefits realized by the buyer.

In Conclusion

This chapter has provided a brief overview of the financial and accounting requirements encountered when making an acquisition in the broadcasting and cable industries. The processes of determining the value of a property, due diligence, purchase price allocations, and accounting compliance are distinctly important, but at the same time interrelated because the establishment of proper values for acquired assets affects all of these areas.

Looking forward, two trends are apparent. First, there has been recognition in the governmental, accounting, and financial communities that the heavy burdens resulting from Sarbanes-Oxley and related accounting standards have in some cases been excessive, and that some relief may be implemented, especially for smaller companies.

On the other hand, there appears to be no deceleration in the profound and complicated changes that are affecting broadcasters and cable operators—including new technologies, increased competition, the Internet, changes in the relationship between television networks and their affiliates, and changes in the advertising economics, to name a few. These changes will ensure that the process of valuing businesses in these sectors will be dynamic in the years ahead, and that related requirements of due diligence, purchase price allocation, and accounting continue to evolve as well.

Finally, there appears to be a movement to further promote the use of the fair value concept in valuation of other assets and liabilities on the balance sheet. This could further complicate the ongoing valuations of assets, and has the potential for requiring technical expertise to assist in the ongoing asset evaluation process because most internal accounting staffs do not have the specialized knowledge to perform these functions.

Notes

1. As discussed later in this chapter, the market approach is indicated as the preferred valuation method for assets in certain financial accounting standards such as FAS 142, although this method is not always practical in the case of certain media intangible assets.