Cover Sheet

The Examination Case

What Managers Do 9528A

Fourth Edition

______________________________________________________________

Name

______________________________________________________________

Address

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Social Security No.

______________________________________________________________

Association/company through which you ordered this course

______________________________________________________________

Telephone No. Date test taken

Please type or print clearly

INSTRUCTIONS: When you have finished your written analysis of the examination case, please complete the top part of this page and return it with your analysis. Make sure to keep a copy of your completed examination for your records. No photocopies will be graded.

Please do not write below this line

Instructor __________________________________

Date Received ______________________________

Do you have questions? Comments? Need clarification?

Call Educational Services at 800-225-3215, ext. 600.

ASSIGNMENT

The Old Geneva Community Bank

INSTRUCTIONS: First reread “How to Take This Course” for directions on analyzing the examination case. Then carefully read this case. When you believe that you fully understand the case, prepare a written answer to the assignment below. In your analysis, use a three-part structure: identify and analyze the issues; outline the possible alternative courses; and give recommendations.

1. Explain Earl Mason’s behavior in terms of need satisfaction.

2. This course discussed the difference between power based on organizational factors and power emanating from individual factors. Discuss this with respect to Oren Dwyer.

3. Analyze the recommendations made by the vice-presidents. What would you recommend? If what you recommend should be put into effect, how would you expect the other people at the bank to react? Discuss specifically the group vice-presidents, the division vice-presidents, and the loan officers.

4. Should any additional changes in the organizational structure, besides those discussed in the case, be made? Discuss.

Donald Fisher, executive vice-president of the Old Geneva Community Bank, was just beginning to realize that he might have a serious personnel problem. The very able vice-president of the main national account division of the bank was leaving. Worse yet, it appeared that this vice-president might actually be taking a cut in pay to work at another midwestern bank. Fisher admitted to himself that if his loan officers did not receive occasional attractive offers from other companies, this reflected badly on the quality of employees of the bank. Still, Earl Mason’s resignation worried him. Why would Mason have been willing to take a cut in pay to leave Old Geneva?

HISTORY OF THE BANK

Old Geneva Community Bank was founded in 1919 by Arthur Fisher, Sr. With very little capital and just five years of banking experience in New York, Fisher received a charter and opened for business in a medium-sized midwestern farming community. After more than a decade of satisfactory growth, the Depression struck, and in the summer of 1930, Fisher was forced to close the bank’s doors. Five years later, however, he reopened Old Geneva in the financial district of the state’s largest city.

Throughout the succeeding years, the growth of the bank closely paralleled the growth of the entire community. Old Geneva, however, was somewhat different from most of its competitors. Statewide banking had been authorized many years before. As a result, a few of the large banks had merged with most of the smaller banks to form a statewide banking structure that was dominated by those few large banks. Old Geneva Community Bank was one of the holdouts from this merger mania and remained independent. The bank’s management liked to point to the firm’s prosperity as evidence that one did not have to be large and statewide in order to compete effectively. By June 30, 1992, the quarterly financial statement showed total assets of over $500 million. More important, at least in the eyes of the bank’s management, the second-quarter statement showed that the bank would probably still belong to the exclusive One Percent Club at the end of the year. That is, despite the year’s tight money, which had recently been easing somewhat, Old Geneva would once again earn over 1 percent on assets, which usually represents a satisfactory return on equity.

Unlike many other banks that seemed to be striving more for high total assets than for profits, Old Geneva had given first priority through the years to maintaining that return of 1 percent. As a result, the bank had certain characteristics. Loan officers, for example, were trained to consider not only the credit rating of an account but also its potential profitability to the bank. Donald Fisher believed that Old Geneva’s criteria for profitability were as carefully thought out and as sophisticated as those of any bank in the country. Indeed, this concern for profit had caused the bank to turn away many creditworthy customers that other banks actively solicited.

Another policy of the bank related to its profit consciousness was its determination to get by with a very lean labor force. As a result, the few commercial loan officers considered themselves overworked. The absence of loan officers who specialized in certain industries or regions was also occasioned by the leanness of the labor force. Both the commercial and the operational areas of the bank worked under tight salary budgets that were seldom, if ever, exceeded.

Organization

In March 1979, the bank had reorganized itself into the Old Geneva Community Corporation, a one-bank holding company that owned 100 percent of the bank’s stock. Although the purpose of this reorganization was to allow for expansion by acquisition, the corporation had made no purchases by the summer of 1992. Its reluctance to expand by acquisition was due partly to a scarcity of good prospects at an attractive price and partly to the attitude of the founding family.

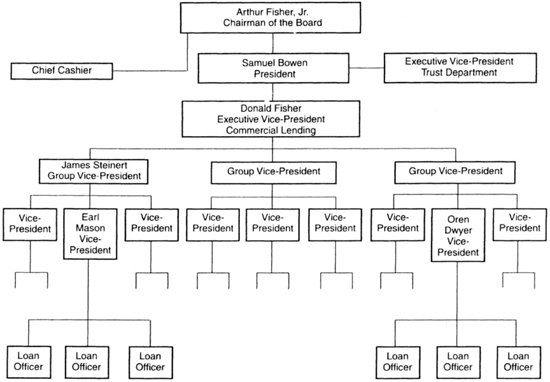

The chairman of the board of the bank and the one-bank holding company was Arthur Fisher, Jr., the son of the founder. (An organization chart appears in Exhibit EC–1.) After Fisher, Jr., was released from the service in 1949, he went to work at his fathers bank as an assistant cashier. His career at the bank had taken him through all the operational and commercial sections, and he was reputed to be the only person in the corporation who could fill in for any absent employee.

When Arthur Fisher, Jr., succeeded to the position of chairman of the board, he sought the services of a good commercial lending officer to take over as president. Although Fisher fully intended to remain chief operating officer, he thought that commercial lending in the bank needed more expert knowledge than he had acquired and that an outside person was needed. He lured Samuel Bowen away from a large Chicago bank and gave him responsibility as president for the commercial lending floor and the trust department. Fisher remained directly responsible for the operations of the bank, and Bowen reported to him.

Donald Fisher’s career at the bank was not unlike that of his father, Arthur Fisher, Jr. He, too, had gone through all of the operational and commercial sections and was currently the executive vice-president. The three group vice-presidents in the commercial lending department reported to him.

Each group vice-president had several divisional vice-presidents as direct reports. According to the organization chart, the divisional vice-presidents, in turn, had groups of loan officers reporting to them. Each separate unit of one vice-president and three to five loan officers was called a division. All the divisions were cost centers, with responsibility for a broad range of bank customers.

Development of a Training Program

Through the years it had become apparent that the kind of person who would become a competent commercial lending officer was usually not the same kind of person as one who worked in operations at the bank. Moreover, to recruit bright young college people, the bank had to provide a special training program separate from the ordinary entry-level training programs for operations personnel. In 1979, the personnel director of the bank had begun recruiting for the credit department. Before that year, every commercial lending officer who had been trained in the bank had spent some time in bank operations.

The credit department consisted at various times of between 12 and 25 management trainees, the credit department manager, and about 10 secretaries. The management trainees, acting as general aides to the loan officers, would spread statements (rework the financial statements of a company to help in credit decisions), handle most overdrafts, check collateral documentation, respond to credit inquiries, and do other fairly repetitive, uninteresting tasks. Only occasionally would they deal with customers. Although these credit trainees reported directly to the credit department manager, their effective bosses were the loan officers.

As a rule, each credit trainee was assigned for eight months to a year to a group vice-president. The group vice-president, in turn, either reassigned the credit trainee to a specific loan officer or simply made the trainee available to a division. The trainee, after completing the eight months to a year of rotation, was reassigned to another group vice-president until he or she had worked under all three. Trainees who were still around after the three rotations were usually made assistant lending officers of the bank; shortly after that, they would become loan officers with customer responsibility.

THE PROBLEM

On Monday, June 29, 1992, Earl Mason, the vice-president in charge of the national lending division (the division that handled all of the accounts of large national companies that were not locally based), resigned. He explained to his superior, James Steinert, that he had decided to accept an offer from one of the largest banks in the Midwest. He felt that although the move would require relocation to another city, it would benefit his career in the long term.

When Donald Fisher first heard about the proposed move, he could hardly believe it. Mason was one of the youngest vice-presidents and probably the most respected. He had graduated from the business school at the University of Chicago and had joined the bank after three years as an Army lieutenant. During his nine years at Old Geneva, he had had an important effect on the bank. He had greatly influenced the training program; he had spearheaded the automatic teller machine (ATM) task force; and most important, he had established and continued some very satisfactory7 accounts.

After discussing Mason’s resignation with his father and Sam Bowen, Donald Fisher decided that it was important that he talk at length with Mason to find out why he was leaving/Mason had arranged to leave work Friday, July 3, and begin a three-week vacation due him. Donald Fisher invited Mason to dinner that Friday on the pretense of asking his advice about a successor. Excerpts from their discussion follow:

FISHER: Earl, now that I know how you feel about who should replace you, I want to ask you why we have to replace you at all. You’ve been at the bank for quite a while and done one heck of a job. If you change your mind, I think you still have a great future with us.

MASON: Frankly, Don, I’m reluctant to go into explicit detail. Why don’t we just leave it that after I thought seriously about everything, I decided that I’d be better off in my career if I were at a larger bank.

FISHER: If it has anything to do with money, let me say, as I think I indicated before, you were in line for a big salary boost this Christmas.

MASON: No, it’s not money at all … In fact, it’s not definite yet, but my new salary might not be as good as my present one. Actually, Don, I want you to know what’s been going through my mind these past few months, but I’ve enjoyed my time at Old Geneva and I don’t want to burn any bridges behind me.

FISHER: I’ve always respected your judgment, Earl, and I’d appreciate hearing how the bank lost you. You can be sure that any personal or confidential remarks will be handled as that.

MASON: Well, let me start by immodestly saying that I think I’m a darn good banker. I may not know all the technicalities of perfecting a security agreement or the like, but I know when to get a perfected agreement, and I know who can tell me how to go about it. While I know there is a lot I can still learn, I’m satisfied that I’m a good commercial banker.

FISHER: You’ll get no argument from me there.

MASON: My feeling is, though, that there has to be more to my career than just deciding on credits, making loans, and opening new accounts. Thinking back on my job lately, I decided that there are only two types of situations that I really enjoy in my work. First, I enjoy working with other people in the bank—to come up with a set of recommendations for top management. The ATM task force I worked on with the cashier, the controller, and the EDP people is a good example of that type of work. The second type of thing I enjoy, and this may sound a little sadistic, is working with a bad loan. When you’re in a secured position on a bad loan, you’re in the driver’s seat, and you can bring all the resources at your command to bear on a specific problem. On the other hand, I no longer get any enjoyment out of the normal duties of a loan officer.

FISHER: Why are you going from bank to bank then?

MASON: That’s a good question, Don. In talking with my new bosses, I decided that they define the job of a vice-president much differently from the way Geneva does. Let me be more specific. Old Geneva makes a concerted effort to put everybody on an equal footing. Even the credit trainees call everybody, except your father, by their first name. Of course, most people think that indicates a healthy environment, and I agree—to an extent. The drawback, it seems to me, is that the middle or upper-middle manager like me gets lost in the shuffle. On the organization chart, I have three permanent loan officers and a number of credit trainees under me. Really, though, I’m just the senior loan officer in the division.

FISHER: I’m not sure what you mean.

MASON: Well, for example, I haven’t the foggiest notion of what any of my loan officers are getting paid. More than that, I don’t even participate in their evaluation, and they know it. The way I see it, I’m a vice-president of a big bank without any management responsibility.

While I’m being so blunt, I might as well tell you exactly what made me start thinking along these lines. A few weeks ago, Jim Steinert sat in on my Monday morning divisional meeting. He usually rotates among divisions and gets to mine every third week. As usual, I let him sit at the head of the table and run the meeting, because that’s the way he wants it. We discussed the liquidation of Stratton Industries and our position relative to the other creditors. After a while, he started lecturing on the Uniform Commercial Code and started testing us on our knowledge of it. When he asked me whether you file in the county or state on farm equipment, I didn’t know, but I did know that I ought to pack my bags. My position at the bank shouldn’t be called a vice-presidency. It’s more like a clerk with some supervisory duties.

FISHER: Well, I’m not sure what to say about Jim Steinert, but there is one thing I would like to say. As you probably know, we’ve been thinking very seriously about setting up another couple of divisions soon and a third in a year or two. You were—and still are, if you want to be—the leading candidate for the job of new group vice-president that would be created by that move.

MASON: Well, I didn’t know these new divisions were coming along. That just proves my point. While I have a fancy title and most of our customers are impressed when they get to talk to me, I’m completely separate from the real management of this bank. My thinking is that in a really big bank like my new employer, no small group of people can make all the management decisions. In fact, you probably know that I have relatively firm assurances that I’ll be a vice-president in charge of their transportation industries division within a year. In that position, I’ll have full responsibility, within certain reasonable constraints, for all the people under me. I’ll evaluate them, decide on their salaries and bonuses, and have hiring and firing responsibility. I might point out that I am doing none of those things right now at Old Geneva.

Your talk of a possible promotion raises one other point that was of overriding significance to me in making my decision to move. I recognize I’m running a high risk in mentioning this, but I think this exit interview is causing me to be a little more open than usual. It struck me some time ago that if I ever wanted to go anywhere in banking, I had only two choices: start my own bank or work for one of the big ones. To prove my point, let’s look at Old Geneva Community Bank. Your father is chairman, and you are executive vice-president. You’ve got a brother in the trust department and a cousin who’ll be starting in the credit department shortly. When I met your 16-year-old son, I decided I might as well get used to calling him “Sir.” Moreover, all middle- and small-sized banking is like that. Frankly, it seems that the only way to get ahead in a bank like this is to be either part of the family or part of another family with important financial connections. I fall into neither category, so the only refuge for me, as I can see it, is a large, national bank in which no one group holds more than five or ten percent of the stock.

FISHER: Oh, Earl, now I think you’re being unfair. If you really feel like that, how do you explain Sam Bowen?

MASON: That’s a good question. My answer is this. First, I’m not sure how much he really influences management decisions, and second, with his graying temples and British accent, I’m not sure if he isn’t more of a salesman or a showpiece than a manager.

Steinert’s View of the Situation

After his talk with Mason, Donald Fisher realized that he had a real problem on his hands. Before he went to his father, however, he thought he should talk with Jim Steinert. After the division meetings on Monday morning, July 6, Donald Fisher talked with Steinert in Fisher’s office. After discussing the problem of succession, Fisher mentioned his talk with Earl Mason. Excerpts from the conversation follow:

FISHER: You know, Earl brought up a lot of interesting points in the talk I had with him the other day. I can’t remember them all, but they seemed to revolve around his not getting any real management responsibility.

STEINERT: I can’t understand that. He is a full vice-president at a very early age. I might add that he became vice-president at a much earlier stage in his career than I did.

FISHER: Well, his point, I think, was that while he had some significant lending responsibilities, he had very few management responsibilities. That is, he had almost nothing to say about the careers of the people under him. He didn’t evaluate them, he didn’t decide on their salaries or bonuses, and he didn’t even have much to say about who worked in his division in the first place.

STEINERT: That raises some broad issues. I’m not sure where to start. First, what do lending officers do? To simplify, let’s say that all they do is make or turn down loans. You and I know perfectly well that even that simply defined task defies evaluation by any simple criteria. That is, there’s no way in the world you or I can decide whether a loan officer is making a good loan or not, except in extreme cases. Even if a loan goes bad, there’s no way we can tell whether the problem could have been foreseen when the loan was made. What I’m saying is that evaluating a loan officer is subjective. You are not evaluating the work; you are evaluating the person. Would it be fair to our loan officers to have them evaluated by a separate set of subjective criteria depending on which vice-president they work with? Would you like some divisional vice-president to sit in judgment of Douglas Beale (a new loan officer of conspicuously limited ability but extraordinary family connections)? He’s potentially worth more money to this bank than anybody but your father and Sam Bowen, yet how would he fare if he were evaluated at the divisional vice-president level?

The way I see it, as we get larger and larger, we are going to have to centralize our decision making much more than we have so far. You’ve got to remember that these fellows like Earl Mason haven’t been in any division of the bank except commercial lending. Their only experience is deciding on credit. Although Earl, with his business school background and his obviously exceptional ability, could probably have been given more management responsibility, who is to say that the next person would be equally capable? We’ve got to protect ourselves against the obvious risk of recruiting lower-caliber personnel as we get larger by centralizing decision making and formalizing the policies and procedures of our bank.

You probably didn’t expect me to be as long-winded as this, but what I am trying to say is that I think Old Geneva is at a critical stage in its career. If it’s going to grow to be an important bank, it has to formalize its control procedures and ensure the same high quality of service it has always provided. The only way to get this done is to give strong direction from the top. As I see it, that’s the challenge that’s facing you and your father.

THE CHAIRMAN’S VIEW

Donald Fisher spent quite a bit of time analyzing the arguments that had been presented. To provide a framework for his analysis, he reflected on banking in general. Since banking was a service industry, the strength of a good bank had to be its people. Although every group in the bank, from the elevator operators to the computer programmers, has its effect on the caliber of the service rendered, there could be no question but that the loan officers were the most important. As Arthur Fisher, Jr., often said, “What we really are is merchandisers. We just happen to be merchandising money. Much like the salesperson or retail clerk, if our loan officers cannot make good, honest deals, we might as well close our doors.”

Donald Fisher believed that through the years the bank had been able to develop some first-rate loan officers, and that was why the bank had prospered. On the other hand, there was a difference between being a good loan officer and being a good manager, and there was no reason to think that the two went hand in hand. A good analogy, Fisher thought, could be made between the good loan officer and the good engineer in a manufacturing firm. There was no reason to believe either one could necessarily manage people.

Recognizing the possibly limited potential a loan officer had for the management of people, Fisher tended to agree with Steinert. That is, in the future the bank was going to have to differentiate clearly between management and commercial lending roles. On the other hand, with this proposed differentiation, how was Old Geneva going to recruit competent people for the commercial lending work? He knew of few business school graduates who would accept a job without some reasonable prospect of a management position. Moreover, he did not know how many of his current vice-presidents and loan officers might be contemplating leaving the bank.

As a rule, Donald Fisher did not approach his father on a problem about managing the bank unless he could clearly define the issues and recommend a specific course. In this case, however, he decided that the problem with Mason probably indicated a much greater personnel problem that was facing the bank. He therefore decided to talk with his father before going any further. After hearing what had happened in Donald’s conversations with Mason and Steinert, Arthur Fisher responded with his evaluation.

“Having been around this bank for quite a while,” he began, “I think I can look back and see fairly distinct stages in our development. In the early years, there was very little differentiation of function. One loan officer, who also happened to be chairman of the board, president, and your grandfather, did just about everything a banker was asked to do. It doesn’t really seem very long ago that I used to keep the combination to the safe myself. As we got bigger, though, we all realized that instead of doing the work, the president had to manage those people who got the work done. I’d call that realization the end of our childhood.

“Then came adolescence. Here we decided that no person could handle all the decisions and keep track of all the people in an organization like this. On the other hand, we also realized that there were some risks in decentralizing the decision making and the management. All things considered, we decided it was best that the chairman of the board not make all the decisions throughout the company. As a first step, we brought in a president and effectively divided the responsibilities of top management between the two of us. After that, we went to the idea of having group vice-presidents and we gave the group vice-presidents many managerial responsibilities. That is our present status, and my guess is that we are probably now in late adolescence.

“The real question Earl Mason’s resignation brings up, then, is how we should go about reaching our maturity. We have a real chance in the next decade to become a large and influential bank, and we have to decide what changes in management structure, if any, will have to be made to do it. Frankly, I’m not sure what to do. On one hand, I sympathize with Earl, and I feel that if we don’t give our vice-presidents some of the responsibility he was seeking, we are going to have trouble recruiting competent people. On the other hand, I hate to loosen the reins on the organization for many reasons. First, although I think I have pretty good working relationships with most of our vice-presidents, I hardly know some of our loan officers. It’s quite a risk to give considerable responsibility to someone you don’t even know. Another problem is that you just can’t shift managerial responsibility without setting up some control mechanisms and some training programs. That could be one heck of a big job.

“My feeling now is that I ought to pass the buck to you. After all, you’re the one who is going to have to live with any big changes that we make now. Why don’t you mull it over for a while and then come back to me with some recommendations?”

THE VICE-PRESIDENTS’ VIEWS

Donald Fisher decided it would be best to hear from more of the vice-presidents. He did not want to risk making a decision on the basis of only one opinion, and a dissatisfied one at that. The best way to go about getting a collective opinion from the vice-presidents, he believed, was to set up a committee including all of them. The committee would be charged with the responsibility for outlining the future role of the vice-president at Old Geneva Community Bank. Donald Fisher purposely excluded from the committee all the group vice-presidents, because he wanted to encourage uninhibited discussion and recommendations. He recognized that there was some risk in setting up this committee. The group vice-presidents, for example, might consider it a threat to their authority. Or the vice-presidents themselves might react unfavorably if their recommendations weren’t carried out. All in all, however, he decided it was a good idea to get their opinions.

Accordingly, at the Thursday meeting of the bank loan committee, where all the vice-presidents and group vice-presidents discussed the chief proposed or outstanding loans, Donald Fisher recommended that the committee be set up. The committee met for the first time on Tuesday morning, July 14. It reconvened every Tuesday and Thursday morning for three weeks, and by mid-August it had come up with some recommendations, as Fisher had hoped. What he had not planned on, however, was that for every recommendation there was a minority opinion. In addition, one of the committee votes divided evenly, four to four. An abbreviated transcript of the vice-presidents’ committee report follows.

We have tried in a few short weeks and a few long meetings to determine how we think the commercial lending operation at Old Geneva Community Bank should develop during the next decade. Our specific perspective was from the position of the divisional vice-president. The focus of our discussion was how we felt that particular position in the bank should be modified in the years to come. Our report represents as accurately as possible the various positions presented at the meetings.

The Training Program

The Majority Opinion. The majority recommends that the training program at Old Geneva be considerably revised. First, we recommend establishing a committee of loan officers to interview and screen potential candidates. Although the personnel department would still play a role in the initial contact, the decision to make a job offer would be shifted from the personnel department to commercial lending officers. Second, we recommend that a candidate be hired by the divisional vice-president for work in a specific division. Since our divisions are not very specialized by region or industry, we see no reason for continuing the rotation among the three groups. In our view, these recommended revisions would not only increase the management responsibility of the vice-presidents, but also place the incoming trainee in a more satisfactory, better-organized environment. The vice-president would, in effect, be in charge of an on-the-job training program and could well be held accountable for the progress of those credit trainees assigned to him or her. There would also be obvious advantages for the division to have permanent credit trainees who would have the time to get to know the division’s accounts.

The Minority Opinion. A minority believes that the present system, although not perfect, should be retained. Our primary concern is for the development of good credit personnel, and we seriously question whether the proposed changes would effectively promote that cause. That is, we believe that each credit trainee must know certain facts before he or she can be a satisfactory loan officer. The present system, which has the trainee reporting to the credit manager instead of a divisional vice-president, provides a forum for transmitting that knowledge. In other words, that common knowledge can be channeled, it seems to us, through the credit manager, whose specific function is to develop personnel. If training and development were left to the vice-presidents or loan officers in the division, the worst that could happen is that they would completely abdicate their responsibilities and let the credit trainee do those tasks that nobody else in the division wants to do. While that is not likely to happen at our bank, it is likely, we believe, that the trainees will get a biased view of commercial banking. Each of us has developed some expert knowledge and some biases over the years, and we are sure to pass these on to the exclusion of other points of view. Moreover, if we are entrusted with the responsibility of introducing a new employee to the world of commercial lending and at the same time continue our customary banking responsibilities, the training program will suffer severely. Finally, we admit that the bank suffers somewhat when rotation requires credit trainees to familiarize themselves with a whole group of new customers. However, we think that this is a small price to pay for developing an informed, well-rounded loan officer.

The Majority Opinion. The majority recommends some revision in the status of loan officers relative to the vice-presidents. At present, all evaluation and salary review is handled at the level of group vice-president and above. We recommend that the responsibility for evaluating loan officers be given directly to the divisional vice-president. We also believe that within certain constraints, it should be our responsibility to set the loan officers’ salary levels and bonuses. We feel that the loan officer’s job is so ambiguous and difficult to define that only constant day-to-day contact, such as that between a vice-president and a loan officer, can provide a sound basis for a fair evaluation. Especially as the bank gets bigger, the ability of a group vice-president to evaluate loan officers fairly will be severely diminished.

The Minority Opinion. A minority of us feels that any change from the present system would be a mistake. Our primary concern is that the proposed functions for the vice-presidents will create a barrier between vice-president and loan officer that does not now exist. It is very important, we believe, that the division operate as a closely knit unit. If the vice-president were making most of the decisions that affected a loan officer’s overall career, it would be hard to maintain the present team atmosphere.

We feel that another important problem would be created, since the loan officers would be graded by too many different scales. More than that, assuming that each vice-president is to some extent committed to the loan officers he or she works with, there will still have to be some apparatus above the vice-presidential level to allocate the limited salary budget among the different divisions. In effect, then, this proposed system would not take the ultimate responsibility away from the group vice-president, and it would create new, unnecessary layers between the loan officer and upper management.

On the Elimination of Accounting by Expense Center

Pro. Half the committee recommends that over several years, each division of the commercial lending department should become a profit center. Our general feeling is that in conjunction with the first two recommendations, profit-center accounting will help to push management accountability for profits further down the corporate ladder. Although this may not seem necessary now, we believe that as the bank gets bigger and bigger, the need for some profit-center accounting will increase.

Con. The four of us who do not agree that profit-center accounting is necessary have different reasons for disagreeing. Our primary concern arises from the obvious impossibility of allocating costs to appropriate divisions and accounts. Profit-center accounting, in our judgment, is the domain of the manufacturing enterprise, where costs by product or by division are far from easily defined.

Another drawback of profit-center accounting, in our judgment, is that this system would tend to create an unworkable arrangement between divisions, which would counter the best interests of the bank. For instance, although we are not now organized by industry, we all know that there is a division of our bank that has gained considerable skill in interim construction loans. Most of us now refer clients who need construction loans to that division. Profit-center accounting, on the other hand, would make us reluctant to refer our clients to other divisions or to share our special knowledge with other divisions.

In our judgment, there are other drawbacks to profit-center accounting. First, it would create the need for more sophisticated and expensive auditing and accounting. Each account would probably have to be looked at individually, and a system of transfer prices would be needed. Second, it could well be that emphasis on profits caused by profit-center accounting would encourage loan officers and vice-presidents to take on high-risk loans, for which they could demand higher interest rates and larger compensating balances. This tendency could act against the long-run best interests of the bank. A final drawback to profit-center accounting is that it is likely to put the trainee in an awkward position. That is, a vice-president who is too greatly concerned with profits is likely to overlook responsibilities for long-term training and development and concentrate on shorter-term, profit-oriented projects. Also, under a profit-center system, a trainee might be given the menial tasks of the division instead of being allowed to spend time in less profitable, but perhaps more important educational work.

Participation in Long-Range Planning

All of use who are expressing an opinion recommended that this committee should not disband on presenting this report. This group should reconvene at least once a month to review the recent progress of the bank and recommend direction for its future. We foresee the creation of subcommittees to investigate specific subjects and perhaps expansion of the membership to include the group vice-presidents. This would be an excellent way for us to become more involved in longer-term corporate planning. We also think that if we help in making decisions, any important program will be greatly facilitated. (It should be noted, however, that while none of us is openly opposed to making this committee permanent, some have no apparent enthusiasm for it.)

OREN DWYER’S VIEW

After Fisher read the report, he tentatively decided that some big changes had to be made in how the position of vice-president was defined at Old Geneva Community Bank. He filled his spare time during the next few days mulling over recommendations he could make to his father. One day, while he was thinking about the problem, Oren Dwyer came in to talk to him.

Dwyer was a vice-president of Old Geneva who had had an unusual career. During the latter part of the 1960s, Dwyer had started his own firm of certified public accountants. After doing quite well for several years, he sold out his partnership for a substantial sum and entered into management consulting. Once again he prospered, and once again he sold his interest for a substantial capital gain. At this point, he became president of a medium-sized suburban bank. After several years there, he decided that a bank presidency was not particularly attractive. He had also had some irreconcilable policy differences with the bank’s board of directors. Since he was by then independently wealthy and had no equity interest in the bank, he decided to accept an offer from Old Geneva, a bank that had had a correspondent relation with his bank.

By the summer of 1992, Dwyer was 56 years old. He had been with Old Geneva for slightly over three years and had been a vice-president for almost two of those years. As far as Fisher knew, he had been happy at the bank, and the bank was very happy to have him. Besides being thoroughly enjoyable and easygoing, Dwyer had attracted a remarkable amount of business. The contacts he had made in the business community were an invaluable asset to Old Geneva. He had come to talk to Donald Fisher about many things, but foremost among them was the series of recommendations made by the vice-presidents.

DWYER: Don, the real reason I came in here was to make sure that you, Sam Bowen, and your father know how I feel about these proposed changes before you make any decisions. Frankly, 1 think many of those majority recommendations could ruin the attractiveness of this bank as a place to work. Now, I recognize that most of our vice-presidents are married, with kids and a mortgage, so you don’t have to worry about their all getting up and leaving when any changes are introduced. On the other hand, I can, and I am not sure that I won’t if things go the way I think they are going to go.

FISHER: As a matter of fact, Oren, no decision at all has been made on those recommendations. I’m glad to have the opportunity of hearing what you think about them before I talk with Dad.

DWYER: Well, Don, you know what I do now. I’m on several boards of directors, I spend a whale of a lot of time soliciting new business, and I’m probably out of the bank more than I’m in. On the other hand, I keep close track of my loan officers, and I know what they are doing most of the time. More than that, I think I know more of the credit people than any other vice-president here. What I’m trying to say is that although I enjoy customer work more than any other part of banking, I don’t think I’ve shirked any traditional management responsibilities.

FISHER: Now, I’ll bet you’re worried about these proposed new responsibilities for a vice-president.

DWYER: That’s exactly it. I don’t want to spend my time like a school teacher filling out evaluation slips, and I don’t care in the slightest what my loan officers and credit people get paid. I enjoy managing people, but I don’t enjoy administration. Those are the things that supervisors do. I make more money for the bank doing other things. You understand, of course, that when I talk about being able to leave the bank if I want, I’m not really threatening to leave. All I’m saying is that, with the duties you might consider giving the vice-presidents, it won’t take long before that job will be considered a very unattractive supervisory position. To maintain its appeal and vitality, you are going to have to make certain that the vice-presidency does not get bogged down with more mundane record keeping.

FISHER: It’s funny you should say that. I was getting the impression that most of the vice-presidents were interested in asserting their roles in the organization a little more strongly by taking on what you see as unattractive, supervision and record keeping.

DWYER: Well, maybe those who are suggesting these new duties are less certain of their positions in the organization than I, but I’m sure I don’t need some extra duties to expand my influence in this organization. After all, Don, we’re dealing with professional people here. You don’t need frequent evaluations to know that they’re all doing one heck of a job. These loan officers have to work hard or they’ll never get ahead, and my sitting in judgment of them and their work won’t help anything. It will probably just create bad feelings. Donald Fisher was now really confused. He was not even sure just what the vice-presidents in his bank did, much less what they should be doing in the future. He recognized that there were conflicts between the objectives of the various division leaders, and that probably no solution would satisfy everyone. He also recognized that changes and growth within the bank might require of vice-presidents management skills that they could not be expected to have without special training. He felt that he had to develop a new job definition for the divisional vice-president’s role that would satisfy both the goals of the people involved and the changing requirements of his growing bank. In preparing his recommendations for his father, he thought that the best place to start was to look at the present management role of the vice-president at the Old Geneva Community Bank. Finally, he still had time to make one final offer to Earl Mason.