7

Retirement Isn't a Solo Project: The Entangled Endearments of Family Relationships

THE GILLETTE TREO™ is the world's first razor designed for shaving someone else. Developed with the help of caregivers, the award-winning design features an ergonomic handle suited to the person doing the shaving, a special non-foaming shaving gel conveniently stored in the handle, and even a safety comb to protect the skin. Gillette points out that there have been 4,000 variations on safety-razor design, but this is the first specifically for caregivers and care recipients.

At the center of the TREO's launch was a multiple-award-winning three-minute ad called “Handle with Care.” It shows a middle-aged New Jersey man, Kristian Rex, together with his son Luke, caring for his widowed father, who had suffered a stroke and was unable to do many things for himself. Rex awakens his father and helps him to the bathroom for a shower, shampoo, and shave. Rex narrates the story, from how as a kid he admired the physique and “Popeye arms” of his tugboat-captain dad to the current role reversal: “Now he needs me to help him out…. It's actually an honor to do that for your father because he did it for me when I was a kid.” Shaving him carefully and conventionally had taken a while, “but I gotta be careful with that face.” The story ends with the father looking good, the three men sharing some wine, and an affirmation of how the generations take care of each other. The camera draws in on Rex as he heartfully reflects, “After I've poured love on my dad all day, he says to me ‘I don't know what I did to deserve you.’ I tell him, ‘I've got you dad. I've got you.’”

Gillette's slogan, “The Best a Man Can Get,” winds up summarizing both the product and the relationship. The ad campaign and even elements of the product itself were created by marketing wizard Leo Savage. Gillette's TREO was named one of the greatest technological breakthroughs of 2018. Seeing the simplicity of this innovation and its appeal – it even won an award at the Cannes Film Festival – it's hard not to be frustrated that so few companies have entered into the caregiver marketplace. This is even more upsetting when you realize that, while 4 million babies were born in America last year, 20 million people became elder caregivers.

The TREO ad introduces many of the key family-related themes we explore in this chapter, including the growing strength of intergenerational connections within families and communities, the special relationships in grandparenting, the many challenges of widowhood and family caregiving, and the countless opportunities for companies and organizations to better engage and serve retirees through transgenerational appeal.

The Changing Family Lifescape

Increasing longevity and changing social norms are redefining “family.” Today, about one American in three is part of a four-generation family – including parents, children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. There's even a growing number of five and six-generation families. In 2001 The New York Times showed the world a glimpse into the future. It wasn't an article about a Jetsons' future with flying cars and super-smart robots. What they featured was even more mind-boggling. It was a story about 118-year-old Sara Knauss. To get your attention, it featured a wonderful picture of Knauss surrounded by her 95-year-old daughter Kitty, her 73-year-old grandson Bob, her 49-year-old great-granddaughter Kathy, her 27-year-old great-great-granddaughter Kristina, along with her adorable 3-year-old great-great-great-grandson Bradley. Welcome to the future!

Partly because of our increasingly mobile and modular lifestyles, blended families have become more common, with two-thirds of remarriages involving children from previous marriages and 40% of Americans having at least one step-relative. One-parent households and LGBTQ-parent households are also on the rise. So are single-person households – including among older Americans who are divorced, widowed, or always single. At the same time, one in five households now contains multiple generations of adults, some 64 million households and rising (Figure 7.1).1 And 4.6 million children live in the same household as their grandparents, almost half of them with no parents on hand.2

In a recent article in The Atlantic, David Brooks concludes that we're seeing the most rapid changes in family structure in history. He describes how the still-idealized “nuclear family” of married couples and 2.5 young children was a twentieth-century phenomenon – and a step in the fragmentation of family structures. Brooks writes:

If you want to summarize the changes in family structure over the past century, the truest thing to say is this: We've made life freer for individuals and more unstable for families. We've made life better for adults but worse for children. We've moved from big, interconnected, and extended families, which helped protect the most vulnerable people in society from the shocks of life, to smaller, detached nuclear families … which give the most privileged people in society room to maximize their talents and expand their options.3

Figure 7.1 Multigenerational Households (in millions)

Source: Pew Research Center, 2018

Today nuclear families are in the minority, and we need new ways to recreate the interconnection, society, support, and resilience that extended families provide. Mutigenerational households and cooperative living arrangements are steps in a positive direction, and the support they offer can be especially important to older people at risk of isolation and loneliness.

Family structures are widely varied and in flux, and organizations seeking to serve retirees should not make assumptions based on yesterday's family structure and relationships. Chances are high that the assumptions will be wrong.

Deepening Relationships and the Reemergence of Interdependence

In our studies, when we asked what facet of life – health, home, work, leisure, giving, finances, family – has been most satisfying, the number-one answer was always “family.”4 In fact, more retirees said family than all those other facets of life combined. Retirees have more time for family and friends, and they relish it. In retirement, while some couples separate – we've all heard the line, “I married you for life but not for lunch” – most couples report growing closer, and other friendships grow more active, especially among single people. Retirees get closer to their children and especially their grandchildren. The most common motivation for relocating is to be closer to family.

As Patricia Thomas, Hui Liu, and Debra Umberson, the authors of “Family Relationships and Well-Being” explain, “Family relationships may become even more important to well-being as individuals age, needs for caregiving increase, and social ties in other domains such as the workplace become less central in their lives.” At the same time, “Family relationships often become more complex, with sometimes complicated marital histories, varying relationships with children, competing time pressures, and obligations for care.”5

We're seeing a rise not just in multigenerational living, but in transgenerational interdependence. It goes up, down, and sideways. Boomer retirees may be supporting or caregiving their elderly parents, who may move in rather than go into assisted care. They may also be supporting adult children who are still trying to gain their financial independence and may “boomerang” back home for a while. The parents are usually happy to receive them, because parenthood doesn't retire. Or retirees may be helping siblings or close friends in need of support. In all these relationships, the feelings of commitment are mutual, with younger generations saying they are ready to support older ones when the time comes.

Intergenerational connection can be core to retirees' happiness and sense of purpose. As Encore.org founder and CEO Marc Freedman told us, “The research about socioemotional connectivity shows we get better at relationships as we age, with more empathy and emotional regulation, and the impulse to express feelings of connectedness. All that adds up to happiness. In this phase of life, people form deep connections that nurture the next generation, and that process not only alleviates social isolation and loneliness, but also provides a deep sense of living a worthwhile life.”

The Generosity of Grandparents

Grandparenting is growing ever more important to family life. By age 65+ over 90% of Americans have grandchildren. That's over 70 million grandparents total, and six in ten are members of the Boomer generation.6 Christine Crosby, founder of GRAND Magazine, told us that grandparenting today is like never before: “We are the first generation of grandparents to hit the planet that has lived this long, and we'll be in the lives of our grandchildren for an average of 30-plus years. There are no roadmaps for us to follow. This is a new path.” Lori Bitter, author of The Grandparent Economy, adds, “Grandparenthood is a time when the future comes into sharper focus. There is a realization of mortality, and of family life continuing after they are gone. Relationships take on greater meaning and a sense of selflessness takes over.”

Eighty percent of grandparents call their grandchildren a top priority in their lives.7 Nearby grandparents regularly provide childcare, and they are the primary childcare arrangement for one in four children of preschool age.8 A recent AARP study found that 45% of grandparents keep in touch with older grandchildren by text, 38% by video chat, and more than 25% each by email and Facebook.9 When grandparents help raise grandchildren, it makes a big difference, as Crosby points out: “There has been tremendous research showing the value that grandparents who play an active role have on the upbringing of their grandchildren – from lower truancy and drug usage to greater confidence in life.”

Grandparents have become a market force unto themselves – and one that's almost always overlooked. For example, when we think of a target consumer population for children's toys, clothes, or technology, the automatic reaction may be to think of their parents. Think again. In America alone, grandparents spend an estimated $18 billion annually on apparel for their grandchildren, $15 billion on toys, and almost $10 billion on vacations.10 In fact, they purchase 25% of all toys, 40% of all children's books, and 20% of all video games. Today's Boomer grandparents aren't just purchasing clothing, sports, and entertainment products for grandchildren when young, but also for them as teenagers and early adults. They may travel regularly to visit the grandchildren. And they invest in grandchildren's futures by contributing to college savings plans. Almost 20% of surveyed grandparents had contributed to a grandchild's college savings or expenses in the past year, an average of $2,337.11 We estimate grandparents' total annual contribution toward college savings at $34.2 billion.

Disney has honed the techniques of marketing to grandparents – and there's a lot that can be learned from them. One in five grandparents has taken a Disney vacation with their grandchildren.12 Walt Disney World's “Grand Adventure” web page provides tools for grandparents planning visits, right down to choosing activities, skipping long lines, making the most of resort and park services, getting tips from insiders, and otherwise “childproofing” the vacation plan. Part of the appeal to grandparents is reliving the fun of earlier Disney adventures as parents with their young children, or even as children themselves.

Several years ago, Ken and his wife Maddy, co-founder of Age Wave, were noticing that many grandparents spent a lot of time reading children's books to their grandchildren. Because they had also read many books to their own kids when they were little, they had noticed that in children's books, there were no elders, or if there were, they were weird old geezers, or nasty crones who were trying to fatten up kids to put them in the oven to eat. They felt that a story was needed for grandparents to read, and even discuss with their grandkids, that would feature the idea that more and more people are choosing to reinvent themselves in maturity. You know, the mom who goes to law school at 45, the person who comes back from a health crisis to run a marathon at 60, the couple who falls in love at 80, the retiree who starts a whole new career.

Ken and Maddy got to work creating a children's book that would tell the simple yet wonderful story of new beginnings. They were fortunate to be joined by an extraordinary illustrator and artist, Dave Zaboski, who had been a senior animator at Disney and had worked on projects like The Lion King, Aladdin, and Beauty and the Beast. What emerged was Gideon's Dream: A Tale of New Beginnings, a modern fable, in the spirit of Aesop, about a caterpillar grub who, after falling off a leaf one day, always dreamed of flying. Then when he got older instead of becoming a worn out old caterpillar, he transformed himself into a butterfly. Since the book was published over a decade ago, they have received countless letters from grandparents thanking them for the magical book and describing how it allowed them to share stories with their grandkids about their own reinventions.

Lori Bitter offers several pieces of advice for marketers trying to engage grandparents. First, like older consumers generally, grandparents are experienced and perceptive. They know when depictions of family interactions ring true and when they do not. Second, the experiences don't have to be expensive, just together with the grandkids – like learning to cook or going fishing. And third, other children are often recipients of grandparents' generosity as they volunteer, donate, and support causes that serve the needs of children generally.

Why Not Turn the Tables?

Thoughtful marketers have noticed that grandparents love to give to their grandchildren, but here's an example of a massive opportunity that's hiding in plain sight. Why not activate the marketplace for grandparents as the recipients of generosity? With those 70 million grandparents in the United States and over a billion worldwide, and with the average grandparent having 4+ grandchildren, why is “Grandparents Day” such a snooze? You may not even know when it is. Hardly anyone does. Since it was established in the United States in 1978, some two dozen countries around the world celebrate Grandparents Day in some form. But the emphasis is on honoring grandparents' contributions, not generosity toward them, and the day isn't a big deal anywhere.

There's four billion grandparent cards waiting to be bought. But let's imagine more than that. What kinds of running shoes might Grandma like? Which new books would Grandpa like to read? And if you can afford it, does he need new golf clubs? Would Grandma like a ticket to Las Vegas? Just as brilliant Chinese entrepreneur Jack Ma hit the bullseye when his Alibaba retail platform promoted “Singles Day,” which swiftly became the biggest and most lucrative annual selling event in the world, there must be a massive grandparent market waiting to be envisioned and unleashed around the world.

Who's the Buyer?

Recognizing grandparenting as a lifestage and tremendous market opportunity raises a key question: who's the buyer? Are elders always the buyers for their children and grandchildren or, as with Grandparents Day, does it also go the other way around?

Lifeline was the first and is still the leading medical alert system, designed to let people summon help at the press of a button on a necklace or wristband. Today such systems are standard fare in medical facilities, senior communities, and the homes of older people living alone. But the product got off to a slow start.

It was developed in the early 1970s by gerontologist Dr. Andrew Dibner. Initial sales to individuals, the target market, were slow, though hospitals showed interest in using it within their facilities. How could such a good idea achieve even more success? The answer lay in the sales data. Checks coming in for the monthly subscription fee weren't always from the persons using the device. They often were from the daughters or sons, the ones who wanted to be sure that Mom or Dad was okay. Lifeline's product was conceived as an alert system for older adults, but they were fascinated to realize that they were also selling peace of mind for the families. The buyers spanned generations and were often happy to pay for such a service to meet both their parents' and their own needs. The product's positioning was adjusted, and the rest is history. Lifeline Systems went public in 1983 and was acquired by Philips in 2006. The latest product generation includes fall detection, advanced location technology, and voice communication. Nearly every technology company has taken note. Even Apple Watch now has an alert system for those – more likely older wearers – in need.

Retirees in their 60s are buying things for their parents, their children, their grandchildren, and of course, themselves. That's four generations. Who is paying for the oldest generation's health and caregiving services? Often the adult children. For the multigenerational family trip? Could be the elders, the adult children, or even the grandchildren. And who's paying for the grandchildren's education? Increasingly the grandparents. For their favorite toys? Same. Who is buying the TREO razor supply? Most likely the son. Businesses would be wise to realize that the retiree market is not just silver-haired consumers buying things only for themselves; it's a far more lively and transgenerational marketplace, unlike anything we've ever seen.

Transgenerational Appeal: No Need for Age-Ghetto Marketing

In Chapter 1, we discussed generational “anchoring,” the use of emblematic people, music, or events to connect with the shared attitudes and experiences of a generation, specifically Boomers. In Chapter 3, we discussed how “universal design” doesn’t stigmatize older men and women. Rather it's design that is smart and inclusive of everyone. Appeals to intergenerational relationships can be just as engaging, and numerous financial services firms are getting very adept at this.

For example, in Principal Financial's “We can help you plan for that” marketing campaign, retirement dreams turn out to be about family generosity. A 2017 ad had retirees moving from their lifetime home to the big city to help their daughter and son-in-law raise the grandchildren, with the tagline, “Be where you're needed most.” A 2019 ad had a young woman moving in with her grandparents to finish her senior year of high school. The grandfather shelves buying the yellow sportscar of his dreams in favor of buying a car for his granddaughter, explaining, “This is my dream now.” Another tells the story of a man taking his father to look at assisted living facilities, then instead building a small house for his dad in the backyard, harkening back to the treehouse his father had built for him. In all cases, empathetic financial advisors make cameo appearances to help make it happen.

In 2017 MassMutual rebranded around the theme of “interdependence,” reaffirming its deep roots as a mutual, or customer-owned, company. The rebranding campaign portrayed interdependence in family, community, and society. For example, the “Two Ways” ad portrays contrasting images of the isolated – a solitary hiker, a tiny International Space Station traversing the moon – and the interdependent – a father helping his son fix a bike, a well-lit Earth at night seen from space. The narration is poetic: “We come into this world needing others. Then we are told it's braver to go it alone, that independence is the way to accomplish. But there is another way to live. A way that sees the only path to fulfillment – is through others.” MassMutual is also incorporating the theme of interdependence into an expanded employee benefits package with more for caregivers, widows and others bereaved, new mothers and fathers, and those wishing to volunteer.13

The Prudential campaign featuring Professor Dan Gilbert is thoroughly multigenerational, without focusing on specific families. The question posed in the commercials is, “Will you be financially ready for a long retirement? One answer is provided by a crowd of people of all ages putting stickers on a large wall indicating the age of the oldest person each has known. It turns into a graph of how long people live past 65. In another ad, people unroll on an athletic field ribbons whose length corresponds to how many years their planned retirement savings will cover. Lori Bitter explains why the campaign is so effective: “It brought people of every age into the conversation about getting older and what that means in term of your finances. You saw children in that ad. You saw older people. You saw Millennials. You saw somebody from every generation taking part in kind of a street event.”

Other products and services, like the Gillette TREO, tap into family connections and transgenerational appeal. A very effective Volkswagen ad portrays family bonds and the power of personal legacy. Adweek recounts the storyline: “A family loses its grandfather. But the tribe bonds during a cross-country trip that their late patriarch never made, driving the brand-new seven-seat 2018 Atlas SUV from one coast to another – through a series of stunning landscapes – to throw his ashes into the great Pacific Ocean.”14 The soundtrack (note the generational anchor) has Simon and Garfunkel tenderly singing “America.”

In 2018 Ralph Lauren celebrated its 50th anniversary with a multigenerational fashion show in Central Park that included babies, adolescents, several gray-haired models, and entire families walking the runway.15 We applaud these kinds of efforts. In 2019, Ralph Lauren's global advertising campaign took the theme one step farther, “Family is who you love,” portrayed eight different families, including a grandmother and her two granddaughters, a father with his three adult children, a father with his adult daughter, a lesbian couple, and families with young children. In one ad, they share definitions of “family,” including “home,” “everything,” and the “center of my world.” But the consensus definition is “who you love.”

Chief Marketing Officer Jonathan Bottomley describes the campaign as “a celebration of the fact that family means different things to each of us – we live in a world where the meaning of family is bigger, broader, and more personal than it has ever been before.” He continues, “While family, love and inclusion have always been the core values that underpin the brand, they're particularly resonant with our consumer today.”16

Challenges Aging Families Face

Connections and commitments may run deep, but family can be a major source of worry as well as satisfaction for retirees. Marriage and family therapy, including intergenerational counseling and mediation, is a fast-growing field. Family issues often involve money, but overcommitment can be personal as well as financial. Retirees can feel stretched too thin, or “sandwiched,” by their commitments to their parents, children, and others. Let's look at two common challenges, one to family finances, the other to family structure.

The Family Bank: Open 24/7

One of the biggest financial – and often emotional – complications in retirement comes from serving as what we've termed the “family bank” and lending, or more often simply giving, money to family members. The web of family interdependencies can keep the bank open 24/7. The family bank may help meet a one-time need such as an extraordinary medical expense, or it could provide ongoing everyday assistance over the course of many years. The most common recipients are adult children, but others include parents or in-laws, grandchildren, and other relatives. Six in ten Americans over age 50 we surveyed have provided financial support to family members in the last five years. Among those who have given or loaned money in the last year, the average amount is $6,500.17 Globally, HSBC reports that 50% of parents provide regular financial support to their children over 18, and 54% provide support to their parents.18

Why do people nearing or even in retirement take on the role of family bank? Generational generosity, whether they can afford it or not. Eight in ten told us, “It's the right thing to do.” And half say they felt an obligation.19 Unlike regular banks, in the family bank the money is typically provided without expectation of repayment. About a third of the time, the banker provides funds without even knowing how they will be used.

Who serves as the family bank? Sometimes the role is predetermined, as when parents support their adult children. But beyond that, family members turn to the person who seems to have the most money, who seems most financially responsible, or who seems most approachable. More than half of those surveyed said they can name the family member who serves as the bank. Being the fiscally responsible and approachable one can backfire.

A surprising number of retirees provide financial support to their adult children. Those who delayed having children or had children in second marriages are increasingly likely to have early adults on the family bank books. And those early adults are taking longer to establish their own financial footing. Seven in ten early adults received financial support from their parents – who are usually in their 50s or 60s – in the last year, and half of them continue to receive support into their early thirties. While most of the financial support is for everyday expenses such as cellphone plans, groceries, rent, health insurance, and automobiles, some parents provide help with big-ticket items like down payments on houses. The total is enormous. The aggregate annual amount spent by all parents on early adult children is over $500 billion – or twice what they put into their retirement accounts. And while we hear a lot about the strain on young people to pay down their college debt, for many it's their parents or grandparents who are footing the bill. Educational expenses for adult children account for one-fourth of that $500 billion.

Some retirement age family bankers feel cornered. One told us, “I thought I would be supplementing my grandchildren's college funds. It turns out I was the college fund.” Another said, “I paid down my mortgage and didn't run up my credit cards. Now everyone in my family is turning to me for money.” Overall, however, generosity prevails: “I'm not looking to get back the money I loaned my daughter. I'm just happy I could help her when she needed it.” But generosity can backfire in a big way when people sacrifice their own retirement savings and financial security to support family members. And it can backfire down the road when today's generosity means being strapped tomorrow, perhaps to the point of needing help in return and becoming a burden on family members, something that people from all walks of life tell us they dread.

Few retirees or pre-retirees anticipate and plan for providing financial support to family members. Nine in ten have never budgeted for such support, including the easily anticipated need to assist aging parents. So support is given without careful consideration of what they can really afford and how much they may be compromising their own retirement finances. An underlying problem is lack of discussion, hence clarity of terms, between giver and recipient. In retrospect, the family bankers often wish they'd established clearer expectations and limits, especially with adult children. And that there were ways to educate family members on how to be more financially independent.

Gray Divorce

People today feel greater permission to move on if relationships aren't working out. Consequently, increasing numbers of retirement-aged couples and their families are disrupted by divorce. In fact, between 1990 and 2015, the rate of “gray divorce” (among those 50 and older) doubled, and among those 65 and older it has tripled.20 Over 30% of Boomers have been divorced at least once, and among the oldest Boomers, born before 1952, it's 37%.21 “The Baby Boom generation was responsible for the extraordinary rise in marital instability after 1970,” say Sheela Kennedy and Stephen Ruggles in their study, “Breaking up is hard to count.” What's behind the instability? “The loosening of legal constraints and declining social stigma has reduced barriers to divorce, and the opening of new economic opportunities for women allowed many to escape bad marriages.”

Gray divorce complicates retirement, both personally and financially. After a divorce, networks of friends shrink, especially for men. And financial assets shrink, especially for women. The average gray divorced woman experiences a 40% decline in household assets.22 And there's less time to catch up, as Susan Brown of Bowling Green State University explains: “You're on the downslope of your career, so your ability to recoup any financial losses are lower compared to if you get divorced at age 35, when you've still got a good 30 more years potentially in the labor force.”23

While divorce is among the most stressful life events, it comes as a relief for some. And while most people try to keep matters private and quiet in a divorce, others benefit from making the event a bigger deal. And there's a market in that. Christine Gallagher, author of The Divorce Party Handbook, has organized more than 200 such parties. The playful celebrations can include cathartic rituals – tossing the wedding ring into the ocean or burning the bridal veil – or fun and games mocking the ex. The divorce party supplies site named “Unknotted” offers “I Don't” cake toppers.

***

In the remainder of this chapter we explore in depth two more family challenges, two common situations where lives are stressed and families rally in support: when retirees serve as family caregivers and when they are widowed. Both can be anticipated but not completely prepared for. And both offer occasions for attentive and empathetic organizations to grow their business while serving and deepening relationships with retiree customers.

The Responsibilities and Rewards of Caregiving

The ultimate display of family interdependence, generosity, and sacrifice comes when a family member needs care. Providing it can be physically, emotionally, and financially draining on the caregivers, but we found in our studies that the overwhelming majority find the experience ultimately rewarding. Most family caregivers say that it brought them closer to their loved one, and they gained satisfaction from knowing that the recipient was being cared for well.24 More than three-fourths say that they would gladly care for another loved one if needed.

Consider three things: increasing longevity, the aging of the enormous Boomer generation, and the significant gap between healthspan and lifespan. Add them up and we see the growing need for caregiving. As former First Lady and Carter Center co-founder Rosalynn Carter put it, “There are only four kinds of people in this world: those who have been caregivers, those who currently are caregivers, those who will be caregivers, and those who will need caregivers.” Many younger retirees are caregivers, many older ones care recipients.

Almost seven in ten Americans turning 65 today will need long-term care services at some point in their lives, and nearly one-quarter of those will need support and services for longer than five years.25 Because the cost of professional care is high (prohibitively so for many), family members step in as informal and generally unpaid caregivers. These informal caregivers provide 1.3 billion hours of help per month to people aged 65+ who are not in nursing homes, and about 40% of that effort serves older adults with dementia.26 Nearly two-thirds of caregivers are women.

One in four retirees say they have dedicated a significant amount of time in retirement to serving as caregiver.27 Their care recipients are most often spouses or parents, although care for other relatives and friends is also common.28 Caregiving expert A. Michael Bloom points out, “With life expectancy rising and medical improvements, people live longer with illness. That means the caregiving journey is longer as well. One out of five caregivers passes away before their care recipient.”

The Variety of Caregiving Responsibilities

Caregiving can begin suddenly when the recipient suffers a setback like a fall. Or it can increase gradually from occasional help to daily assistance to continual care. The duration can be brief – the recipient who fell had a hip replacement and recovered nicely. Or indefinite if the recipient has a gradual debilitating condition like Alzheimer's. Care most often takes place in the recipient's home, and 14% of the time the caregiver lives there as well, but one-third of the time the recipient moves into the caregiver's home.29

The caregiving process depends on the recipient's mental and physical condition and trajectory. As the recipient's needs increase or communication capability declines, caregiving can become more physically difficult and emotionally stressful. Yet most family caregivers let the load increase without getting additional support, and social isolation can become a problem for caregivers. Another big variable is the relationship between caregiver and recipient. Caring for a parent usually involves more of a role reversal than caring for a spouse.

Caregiving can include a variety of services (Figure 7.2). We may think first of physical care – help with eating, bathing, dressing, toileting, getting around. But the heart of caregiving can be emotional and social support, including companionship, conversation, everyday leisure activities, and transporting the care recipient to see friends. A recipient who does not need much personal care may still need household support, like cooking, cleaning, shopping, or medical support, such as managing medications and appointments and performing some basic nursing procedures.

Figure 7.2 Services Provided by Caregivers

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, The Journey of Caregiving: Honor, Responsibility and Financial Complexity

Another important role is care coordination, organizing and monitoring the activities of the caregiving team. With that much potential work to do, many families make caregiving a group endeavor, where one person serves as primary caregiver and usually coordinator, and other family members fill in on a regularly scheduled or as-needed basis. As we'll discuss in more detail in Chapter 8, paid professional caregivers are part of the team in about one-quarter of caregiving situations, most often to help older recipients with physical care.30

Family caregiving is the most common situation. But what happens if no family is around? The emerging and expanding “share the care” model organizes local volunteers to collectively provide care and serve as the recipient's extended “family.” When we talked with Michael Adams, a Stanford-trained lawyer and CEO of SAGE, the advocacy and services organization for LGBTQ older adults, he explained, “Because many LGBTQ people don't have adult children, they can't expect built-in care from family or family caregivers as they get older. Many are recognizing that at some point, they may well need community support and care. Some people I know are thinking about and exploring ways of creating their own kind of Share the Care communities.” SAGE research finds that 30% of older LGBTQ people are very or extremely concerned about not having someone to take care of them, and 32% are just as concerned about being lonely and growing old alone. Among older heterosexual, cisgender people, less than 20% share those fears.31 This creates both challenges and opportunities to serve the LGBTQ community.

Financial Caregiving

Caregiving is an intensely personal commitment. It can also be a major financial one. Our studies have revealed that over 90% of caregivers are also financial caregivers, contributing money directly or performing financial coordination tasks on behalf of the care recipient (Figure 7.3). Nearly two-thirds of caregivers do both.

Those making direct financial contributions average $7,000 a year.32 The money usually pays for a mix of personal, medical, and general living expenses, with the biggest categories household (41% of the total) and medical expenses (25%). But out-of-pocket expenses can be a lot higher, especially when caring for someone with dementia. Three in ten family caregivers who contribute financially say it causes them financial difficulty.33 But the majority aren't tracking and don't even know how much they are spending, especially for background expenses like their own transportation.

Financial caregivers also pay bills and manage bank and credit card accounts, and they commonly handle insurance policies, prepare taxes, and manage investments. They should also be a major line of defense against elder financial abuse, starting with monitoring accounts of all kinds. As a recipient's condition declines, these responsibilities expand. The financial caregiver may play an ongoing role getting and keeping the recipient's financial and legacy affairs in order.

Figure 7.3 Financial Coordination Tasks of Caregivers

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, The Journey of Caregiving: Honor, Responsibility and Financial Complexity

Nearly 12 million care recipients need full assistance managing their finances. But nearly half of their financial caregivers do not have the legal authorization, such as a durable power of attorney, to perform all the roles they play.34 And three-fourths of family care-givers haven't even discussed their financial roles with the care recipient. That reticence may be due to the recipient's mental condition, but more often it's a matter of family taboos about discussing finances, plus the fact that the caregiver just gradually assumed financial roles. In short, financial caregiving merits more acknowledgment and discipline than it generally receives. And we must note that, although it's unconscionable, financial abuse of elders is on the rise, with some of it perpetrated by family members who take money or possessions or try to force changes in their favor in the care recipient's will.

Serving Caregivers

Caregivers' personal finances can be stressed by contributing directly to the recipients' care and by the opportunity cost of the time spent in caregiving. The latter can be very high if the caregiver must cut back on work, reducing both income and retirement savings. Seventeen percent of Boomer caregivers have retired early or quit their jobs, and 21% have reduced hours or job responsibilities as a result of becoming caregivers.35 Caregiving can also take a toll on the caregiver's health, and thus health expenses. Two-thirds of caregivers said they could benefit from financial advice.

A variety of services and guides are appearing to ease the work and challenges of caregivers. Target's “Caregiver Essentials” web page curates useful products, such as pill planners, blood pressure monitors, and over-the-counter drugs. For caregivers, they offer smart home products, stress-relief products, organization and planning tools, and helpful books on caregiving. They also provide caregivers with flexible shopping options including subscription service, same-day delivery, and curbside pickup. We expect to see many more services customized to caregivers' needs in the future, and whatever the products or services may be, 40 million family caregivers, and 20 million people becoming caregivers each year, is a very large market.

Caregiving may be a high-touch activity, but a wide range of rapidly evolving high tech can help make caregivers' work and lives easier. For example, in-home patient monitoring and treatment can revolutionize the medical side of caregiving. Caregivers can monitor recipients remotely, check in with them electronically, and be alerted by medical response services when called. Through telemedicine, physicians and nurses can “visit” patients in their homes. And caregivers can use apps for tasks including monitoring the recipient's medications, refilling prescriptions, and making medical appointments. For everyday health services, CVS in-store Minute Clinics provide basics. Most CVS stores have a Higi Station, a wheelchair-accessible booth where caregivers and recipients can get health readings such as blood pressure, pulse, weight, and BMI. Caregivers can also now get online training and real-time assistance when performing nursing tasks. Recently, after caregiving her mom who had early stage Alzheimer's, Carrie Shaw created the Embodies Labs company, which uses cutting-edge virtual reality technology to teach caregivers – both family and professional – how to empathically understand the world from the point of view of their loved one, and thereby provide more respectful and sensitive care.

Services are also cropping up to assist the financial caregiver. The Care.com HomePay service helps family members who hire home care workers with payroll, tax, and other mandated tasks. It also provides access to financial professionals and assistance in hiring home care workers. The True Link service provides prepaid cards for care recipients with settings to prevent certain purchases, such as from telemarketers, and alerts to family members about large purchases. The cards can also be issued to caregivers to make specific purchases.

At the end of caregiving, caregivers may need to reset their own personal and family finances, especially if the recipient has passed away, because caregivers are often heirs. A widowed spouse-caregiver is often the primary or sole heir, and it's common for children-caregivers to receive special consideration in the recipient's will. The experienced retiree-caregiver is better prepared should another loved one need care and has had an advance look at what life would be like as a care recipient. For many retirees, caregiving ends with the death of a spouse, and they enter our next personal and financial crossroads, widowhood.

The Journey of Widowhood

When couples grow old together, the marriage ends with the death of a spouse. The death may be anticipated, but the transition to widowhood is almost always highly upsetting and traumatic. On the Holmes and Rahe life change scale, the most stressful life event is the death of a spouse.36 Fortunately, family and friends can provide immediate and ongoing emotional and pragmatic support, and those relationships often deepen.

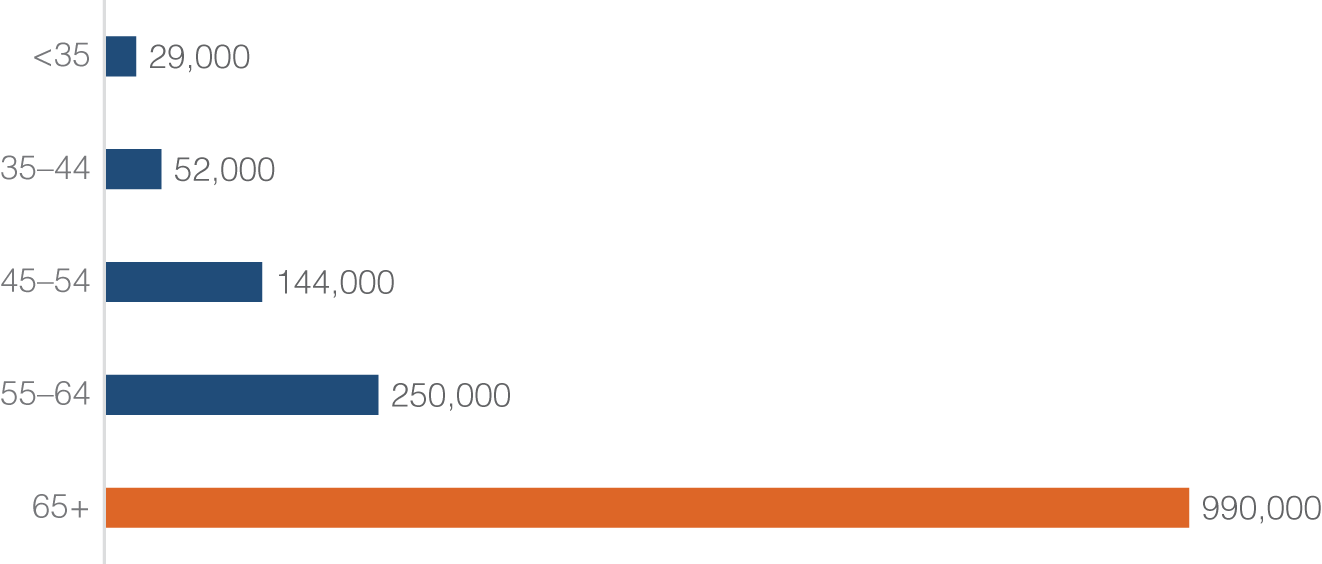

Fifteen million Americans are currently widowed, and five million more have been widowed and then remarried.37 Each year, 1.4 million Americans are newly widowed (Figure 7.4). In half the cases, the new widow had been serving as caregiver to the deceased spouse. And over three-fourths of the currently widowed are women.38 That's because women have superior longevity and tend to be, on average, 2.5 years younger than their husbands. It's also because widowed men tend to remarry more than widowed women do. Among all Americans over age 65, 32% of women and 11% of men are widowed.39

Figure 7.4 Prevalence of Widowhood: Americans Widowed in 2019

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2018 American Community Survey, and Marital Events of Americans, 2009

The new widow is suddenly the primary – or lone – decision maker, and there are so many decisions and actions to take. Two-thirds of widows say that in the beginning of their grief they had too many things to do and didn't know where to start.40 Funeral arrangements to make, death certificates to obtain, financial accounts to reassign, and eventually an estate to settle. Paperwork and logistics intrude upon the chance to grieve. One widow articulated the common plight: “The world is not sympathetic to what you're going through. They don't give you any time to grieve properly…. Your life is suddenly in probate. You can't take even a few days to process what's just happened to you because the business demands taking care of, and the business is not simple.”41

Emotional Adjustments

Widows make emotional and practical adjustments at different paces. Although some widows never recover from the loss of their spouse, our research showed that after approximately three years of grieving and adjusting, the physical and emotional health of widows typically returns to normal levels, or we should probably say to “new normal” levels. Many widows discover resilience they weren't sure they had, and more than three-quarters of widows said that after losing their spouse, they discovered courage they never knew they had.

Many widows deal with tension between preserving the past and creating a future. Their progress may be measured in milestones: When to deal with the spouse's clothing and personal effects. Whether to take the trip they'd planned. When to begin to socialize as a single person. Progress can be complicated by their responsibilities when widows have jobs, have children living at home, or are caring for parents. And progress can be impeded by health issues. Especially early in widowhood, the chances of serious illness and depression can rise.42 It's worth noting that while modern society has a wide range of products and services to help people plan for and adjust to both marriage and parenthood, the other side of the lifeline is far less attended to and creatively supported. This ties in to Dr. Robert Butler's notions about gerontophobia. Because we're uncomfortable with death, many needs go avoided or even unnoticed by youth-focused service providers.

Financial Challenges and Surprises

The financial transitions and challenges of widowhood are several and significant (Figure 7.5). While widows commonly experience a drop in income, they also often see a substantial rise in assets as bank and investment accounts, real estate, and other assets transfer mainly into their control. Many also become the recipients of life insurance payouts. So there are many widows at each end of the economic spectrum, including with high home equity or net worth. Ironically, at present, the highest concentration of poverty is among single older women, while at the same time, the highest concentration of wealth is also among single older women. However, even the affluent widow can face the immediate challenge of lack of cash because assets in the late spouse's name may not be accessible until the estate is settled, and assets like real estate aren't liquid.43

At the start of widowhood, many feel stressed about immediate expenses, with funeral costs coming on top of regular housing and health and other costs. Widows may need to remix their everyday finances and eventually make bigger adjustments to maintain their lifestyles and protect their assets.

Figure 7.5 Financial Challenges of Widowhood

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Widowhood and Money: Resiliency, Responsibility and Empowerment

The key word is “eventually.” Many widows report feeling pressured to make financial decisions quickly, including from well-intentioned family and friends offering unsolicited advice. The experts say it's important to distinguish decisions that need immediate attention from those that don't. Big decisions should wait: “Don't put your house on the market. Don't give away money to your children or charity. Don't sell stocks or bonds. Eventually, any of these steps may make perfect sense. But take a breather in the overwhelming weeks and months after a spouse dies.”44 Experienced widows advise new ones to avoid making major financial decisions.

Over time, widows prove resilient financially, just as they do emotionally. Only 14% of widows say that they were making financial decisions on their own before the spouse died. As widows, 86% do so.45 They adjust their everyday finances and then they look ahead. Widows are much more likely than married couples of the same age to have wills, advanced health care directives, and designated powers of attorney. Experience brings confidence. Over 70% of widows consider themselves more financially savvy than other people their age.

Serving the Newly Widowed

Organizations that recognize widowhood as a distinct and important lifestage are developing innovatively pragmatic services. For example, Peacefully is a service that takes care of the “loose ends” of life, so that surviving loved ones can focus on what matters. It helps people deal with tasks including notifying Social Security, canceling utilities, dealing with social media, and transferring bank accounts. The start-up was inspired by a Millennial entrepreneur's experience watching her family struggle with all the immediate burdens after they lost her grandmother.

Created in 2001, Everest describes itself as “a funeral concierge service rolled up into a life insurance plan. When help is needed, we are one call away. We are there to guide families through a very emotional, complicated, and confusing time in their lives…. Everest has combined on-demand, personalized service, technology and consumer advocacy to revolutionize traditional funeral planning.” When help is needed, Everest advisors are ready to personalize the funeral plan, compare and negotiate prices on funeral homes and products, and work with life insurance companies to get monies to the beneficiary quickly. Families can make informed decisions without having to research their options. Everest can be purchased directly, obtained as an add-on to a life insurance policy, or sometimes accessed as an employee benefit. More than 25 million people in the United States and Canada are covered by Everest.

Other services to ease the immediate challenges of making funeral arrangements include Parting.com, launched in 2015, and Funerals360, launched in 2017. Both help people find the right funeral home, comparing the services and costs of funerals and cremations by local area.

Undertaking LA brings the funeral director to the home of the deceased and walks family members through the death rituals, such as washing and dressing the body and holding an in-home wake. The entrepreneurial pioneer of this enterprise is Caitlin Doughty. In addition to her years as a mortician, she has taken on our modern discomfort with death and travels the world speaking on the history of death, including its culture, rituals, and the funeral industry. In 2011, Caitlin founded the Order of the Good Death, a death acceptance collective that has been featured everywhere from NPR to the BBC to the LA Times. She produces a web series, “Ask a Mortician,” and wrote a book, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory, which was a New York Times bestseller.

Financial services firms try to ease the complexity of widowhood with services specifically designed for when a loved one passes away. For example, specialists on the Survivor Relations Team at USAA create a “dashboard” overview of the steps necessary to manage and settle accounts, including how to submit required documents electronically. A variety of other resources provide guidance, and USAA offers survivorship consultation with specially trained financial advisors.

When a spouse passes away, money and other assets go in motion to the widow and also to children or other family members in many cases. That makes it a delicate time for financial services firms because many widows change banks and almost half of widowed women change their advisors.46 Sometimes they switch under the influence of family or friends. Kathleen Rehl, financial planner, author, and widow, points to another cause: “In that early stage of widowhood, it is critical to have someone that you can think things through with – not tell you what to do. That's why many widows leave the advisors because the advisors try to tell you what to do.” Rehl is a faculty member of the Financial Transitionist Institute, where they teach advisors to establish “decision free zones®” by helping clients understand what decisions can be placed on hold while they're grieving and where an immediate decision is really needed.

The widows we surveyed offer good advice to the financial professionals trying to serve them (Figure 7.6), starting with turning down the pressure to make decisions.

Of course, the best way to protect the customer relationship is to have been serving the couple all along, including helping them prepare for the eventuality of one of them dying. That includes the seemingly mundane details of making sure that accounts are in both names, key documents are accessible, and cash can be available. Couples need that basic help: more than half of widows say that they and their spouses did not have a plan for what happens when one of them passes away, and three-quarters of married retirees say they would not be financially prepared if their spouse died.

Figure 7.6 Advice from Widows to Financial Professionals

Source: Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Widowhood and Money: Resiliency, Responsibility and Empowerment

Notes

- 1. D'Vera Cohn and Jeffrey S. Passel, “A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households,” Pew Research Center, 2018.

- 2. Generations United, “A Place to Call Home: Building Affordable Housing for Grandfamilies,” 2019.

- 3. David Brooks, “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake,” The Atlantic, March 2020.

- 4. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Family in Retirement: The Elephant in the Room, 2013.

- 5. Patricia A. Thomas, Hui Liu, and Debra Umberson, “Family Relationships and Well-Being,” Innovation in Aging, 2017.

- 6. AARP, 2018 Grandparents Today National Survey; Sabi, The BOOMer Report 2015.

- 7. Marketing Sherpa, “How To Market To Grandparents – Q&A on Tips, Tactics and Results,” February 3, 2009.

- 8. Lynda Laughlin, “Who's Minding the Kids? Child Care Arrangements: Spring 2011,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2013.

- 9. Patty David and Brittne Nelson-Kakulla, “Grandparents Embrace Changing Attitudes and Technology,” AARP Research, 2019.

- 10. Age Wave calculation based on TD Ameritrade, Millennial Parents Survey, 2017, and Sabi, The BOOMer Report 2015.

- 11. TD Ameritrade, Millennial Parents Survey, 2017.

- 12. Suzanne Rowan Kelleher, “The Grandparent's Planning Guide to Walt Disney World,” Trip Savvy, June 26, 2019.

- 13. “MassMutual Significantly Expands Suite of Employee Benefits,” MassMutual press release, January 9, 2019.

- 14. Patrick Coffee, “Volkswagen Looks for America, With Help From Simon & Garfunkel, in This Poetic Cross-Country Trip,” Adweek, May 1, 2017.

- 15. Opheli Garcia Lawler, “Oprah Gives Loving Toast to Ralph Lauren,” The Cut, September 7, 2018.

- 16. Emilia Petrarca, “Ralph Lauren Expands Its Definition of ‘Family’ in a New Campaign,” The Cut, March 28, 2019; Rosemary Feitelberg, “Ralph Lauren Unveils New Global Campaign, ‘Family Is Who You Love,’” WWD, March 28, 2019.

- 17. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Family in Retirement.

- 18. HBSC, The Power of Protection: Facing the Future, 2017.

- 19. Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Family in Retirement.

- 20. Renee Stepler, “Led by Baby Boomers, divorce rates climb for America's 50+ population,” Pew Research Center, March 9, 2017.

- 21. General Social Survey, NORC at the University of Chicago.

- 22. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Retirement Security: Women Still Face Challenges, 2012.

- 23. Susan Brown interviewed by David Baxter of Age Wave, July 17, 2013.

- 24. National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP Public Policy Institute, Caregiving in the U.S. 2015.

- 25. “How Much Care Will You Need?” LongTermCare.gov, 2017.

- 26. Judith D. Kasper et al., “The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia on Family and Unpaid Caregiving to Older Adults,” Health Affairs, 2015.

- 27. Nonprofit Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, A Precarious Existence: How Today's Retirees Are Financially Faring in Retirement, 2018.

- 28. Caregiving in the U.S. 2015.

- 29. Nonprofit Transamerica Institute, The Many Faces of Caregivers, 2017.

- 30. Ibid.

- 31. SAGE, Out & Visible: The Experiences and Attitudes of LGBT Older Adults, Ages 45–74, 2014.

- 32. AARP, Family Caregiving and Out-of-Pocket Costs: 2016 Report.

- 33. Unless otherwise noted, survey results in this section are from Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Journey of Caregiving: Honor, Responsibility and Financial Complexity, 2017.

- 34. Gary Koenig, Lori Trawinski, and Elizabeth Costle, “Family Financial Caregiving: Rewards, Stresses, and Responsibilities,” AARP Public Policy Institute, 2015.

- 35. Transamerica, The Many Faces.

- 36. Holmes and Rahe, Life Change Index Scale.

- 37. U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Marital Status Tables, 2106.

- 38. U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2016

- 39. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2018.

- 40. Unless otherwise noted, survey results in this section are from Age Wave / Merrill Lynch, Widowhood and Money: Resiliency, Responsibility and Empowerment, 2018.

- 41. “The world of the widow: grappling with loneliness and misunderstanding,” The Guardian, October 5, 2015.

- 42. Sarah Wilcox et al, “The Effects of Widowhood on Physical and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Health Outcomes: The Women's Health Initiative,” Health Psychology, 2003.

- 43. Charlie Jordan, “Widows with wealth: Managing money after losing a spouse,” CNBC, October 31, 2017.

- 44. Susan B. Garland, “A To-Do List for the Surviving Spouse,” Kiplinger, September 1, 2011.

- 45. Survey of Widows and Widowers Topline Report, The American College State Farm Center for Women and Financial Services / Greenwald and Associates, 2016.

- 46. Ibid.