CHAPTER 2

Lapdogs, Dobermans, and Retrievers: Motivating the Breed that You Need

AT THE EDGE OF PHILADELPHIA’S CENTER CITY we inched along the Schuylkill Expressway, nicknamed the “Sure Kill Distress-way” for what some say is the traffic and others say are the resulting accidents. It was just after 9:30 a.m., it was already hot, and traffic was still jammed from rush hour. Tony, a salesman for a shipping services company, was driving as we headed to see a manufacturer that was one of his largest accounts. The pace of the traffic foreshadowed the sales call we were about to have.

As we pulled into the parking lot of an aging distribution center, Tony told me his plans. “I’m glad we got out to this customer ’cause I’m gonna be on vay-cay next week and I won’t be able to get back here prob’ly till next month.” Vay-cay was clearly on Tony’s mind, and it wasn’t just about next week. It was in his DNA. Tony was a lap dog.

We met the customer, John, a distribution manager, in a cluttered office. We spent about 40 minutes in the building; less than 10 minutes of that was with John. Was John really the customer—the decision maker? John and Tony’s short conversation was about what major shipments they had coming up and some late pickups from Tony’s company that caused John some irritation. Sure, John made the day-to-day decision on which carrier he’d use from his selection of LTL (less than truck load) and long haul shippers scheduled on his bulletin board. But was John really making the decisions that could get Tony’s company a bigger share of the business and move some of those competing shippers off the bulletin board? Was Tony missing something, someone, some need?

Tony had been selling shipping services for about 20 years and was clearly comfortable in his role. After a short conversation with John, Tony strode out into the warehouse, where he spent the next 30 minutes or so talking to the employees and taking cube weights using a measuring tape to estimate the density of what seemed like a random selection of full shipping boxes on various racks in the warehouse. He explained that this was to get an estimate of what volume the company was shipping. A question came to my mind: “Is this helping the customer with his business, or is it about compliance with Tony’s company’s operations standards?”

When we were done with the “sales call,” we got back into Tony’s car. I was ready to go, but Tony still had some work to do. He opened up his folder, which contained a stack of preprinted sheets with lots of lines and boxes to fill out. “Gotta complete the call report before we go,” he told me.

Tony’s goal wasn’t revenue or volume or even really hitting his quota. He was simply doing what he had been groomed to do over the course of 20 years—operations with a sprinkling of customer relationship time. In fact, when we got right down to it, Tony was measured on shipping volume, which changed little from year to year over his base of large accounts, and on customer contact time. Customer contact time, according to company practice, was a measure that was related to “sales success.” For Tony, and for most of the reps in his organization, customer contact time included not only the brief conversation with the distribution manager but also that time in the warehouse and even that little time extender in the parking lot filling out the call report.

Back at the home office, the sales SVPs complained relentlessly about the sales organization. “They’re a pack of lap dogs. They’re not out hunting down new business. They’re just taking orders. They’re overpaid service people. Why don’t they have the drive to get out and find some new volume?”

The shipping business had become tougher and more competitive over the past 10 years, and the major players were being outrun by smaller and more aggressive competitors. The truth of the matter was that if the company’s strategy was finding new business, they had the wrong breed of dog. The company had been breeding lap dogs for decades, and in this new competitive environment, that dog didn’t hunt. The company needed Dobermans to get new customers, or at least Retrievers to search out new business in their current accounts. It was a very tenured sales organization, and as the saying goes, they couldn’t teach the old dogs new tricks. Tony and his peers were decades into their behavior patterns, and re-training lap dogs to be Retrievers was dubious at best; and they certainly couldn’t expect them to behave like Dobermans. The company had invested too heavily in the wrong gene pool. They needed a change of breed and a change of sales compensation to motivate and drive the performance of their business.

Organizations change, as do sales strategies. As those strategies are modified, sales roles either evolve or fail. One CEO with whom we recently worked pays close attention to the variety of sales roles supporting his sales strategy year after year. “I want to be involved in structural issues with the sales organization,” he says. “With a new business developer and account manager structure, I’m willing to pay higher for the new business developer. I’m fine with paying people a lot of money as long as it’s a good cost of sales. But I want them to be hungry. That pay has to be pay for performance. To provide the lifestyle they want, these reps have to hunt and kill. Some of our top performers do their best work on Saturdays and Sundays. The hungrier, the better.”

What Breed Do You Need? Aligning Sales Roles to Revenue Flows

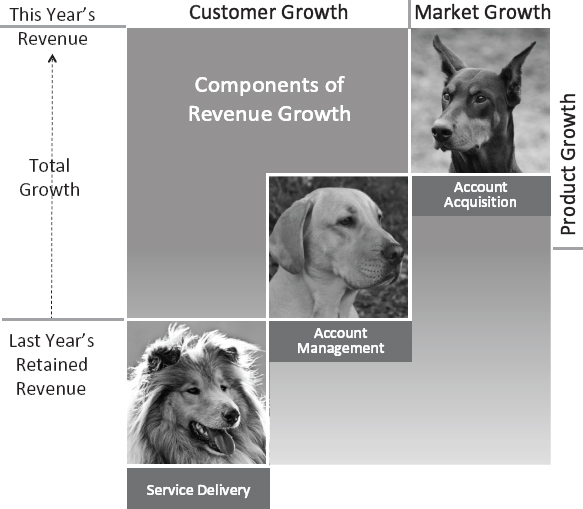

When companies grow from year to year, they don’t grow in a straight line. They hold onto some revenue from current customers, they lose some revenue and customers, and they grow in other areas. Analyzing the ebb and flow of revenue and profit can help a company understand how it grows, plan for future growth, align sales roles, and motivate the right results in those roles.

The Three Strategies for Revenue Growth

The dimensions of buyers (both current customers and prospects) and offers (current and new products or services) describe a range of possible revenue flow opportunities, as illustrated in Figure 2-1. Among the possibilities are really just three basic strategies.

1. An organization can retain the revenue from its current customers, which is called retention selling. While it may not actually lose any customer companies from one year to the next, an organization usually loses some of its current revenue from current offers. It’s deceptive. The customer remains, but some of the business is lost. In fact, the average business-to-business sales organization retains only about 84 percent of its prior year’s revenue. So, to grow it has to find new revenue.

FIGURE 2-1. COMPONENTS OF REVENUE GROWTH.

2. A company can grow revenue from its current customers, which is called penetration selling. Penetration selling breaks into two different types of selling. Buyer penetration is gaining additional buyers for the same product or service. For example, a shipping company that focuses on ground transportation would try to get more buyers within the same large customer account to use its services instead of another carrier or shipping method. Product penetration is growing with additional products the customer may not be purchasing. So that same shipping company might capture more current customer growth by selling its air shipping service to a customer that’s already using its ground service.

3. A company can create revenue through new customer selling, which also breaks into two types. New competitive wins provide growth through new customers that are already purchasing similar products from competitors. The shipping company may win a new contract for international shipping from a competitor that held that business last year. New market selling is developing a new opportunity with a new customer that hasn’t purchased that product before. For example, the shipping company may offer logistics services to a new customer to help the customer improve the operations of its warehouse facilities. Of course, this strategy could ultimately result in the company winning the customer’s shipping business, too.

Figure 2-1 is a good tool to plan coverage and sales roles and determine what breeds of seller the organization needs.

Sales Roles and Their Canine Counterparts

How does each of those potential revenue flows connect to the sales organization? Each significant revenue and profit growth area should have an associated plan to capture that growth and a sales role or set of roles to execute that plan. Ensuring that the sales compensation plan makes sense for the sales roles is fundamental. “The most important thing to me is having the right jobs and the right people,” says Doug Holland of ManpowerGroup North America. “It sounds very simplistic, but the comp plans are only as good as the right roles. And if jobs are not designed in a way that drives that strategy, then chances are the comp plan will be in conflict with the job design, or it will be in line with the job design and the strategy won’t be met.” In Holland’s view, a CEO or a president sets that expectation. “It’s very easy to knee jerk and say, ‘The comp plan is broken,’ instead of asking, ‘Have we taken the time to really lay out our business strategy? Do we have the right people in the right jobs?’ A CEO or president has to make sure to have the right strategy, the right structure, and the right people before he or she thinks about compensation,” he says.

Making certain that the organization understands the sales roles guarantees a firm foundation on which to build a sales compensation plan. It’s fundamental, yet it’s surprising how many times we walk into companies and find that the plans are out of alignment with the strategy or out of alignment with the sales coverage model.

When describing sales roles and personalities, we prefer the canine model to the more common hunter/farmer metaphor because it’s more descriptive and brings the cast of characters to life. It’s possible that a farmer could become a hunter, but most breeds of dog simply cannot change from one species to another. There is an abundance of sales coverage options for most companies to execute the growth plan, and the canine breeds represent the many options and characteristics of the roles that need to be defined and compensated. Figure 2-2 illustrates how some of these breeds go to market.

FIGURE 2-2. DOBERMANS, RETRIEVERS, AND COLLIES.

Dobermans

Dobermans are the alpha dogs, always on the prowl for new opportunities. There are at least two types: the competitive steal Dobermans who are going after the next big new account sale, and long-term business developer Dobermans.

If you know a Doberman, you know they’re in continuous motion. A friend of mine, Bill, exemplifies the typical Doberman profile. He is very externally focused. Walk into his office and he’s guaranteed to have at least one phone to his ear. To the side of his desk you might find a couple of cell phone batteries discharged like empty bullet clips as he moves to his next call. He’s the quintessential relationship developer and always seems to be reaching out to someone new. Bill can usually make a first- or second-generation connection with any given prospect because his network is so deep, but he blends connections with competence. He’s not an empty suit; he knows what he’s talking about, listens to the customer first, and is skilled at quickly adapting his bag of solutions to align almost perfectly with the customer’s needs.

When he makes a sale, which is not infrequently, he pauses to celebrate but never stops moving for long because his internal drive keeps pushing him forward in a quest for the next opportunity. Does Bill meet rejection? Often. But he never sees it that way, and that’s the attitude that keeps him going. Rejection just slides off his back—there’s always the next prospect.

Like a well-trained Doberman, Bill will be your best friend, but try to take his bone and you may lose a hand. Dobermans are super competitive. If you are a current customer of Bill’s, as much as you loved him during the sales process, don’t expect him to be by your side for long unless you’ve got another bone. Because of his lack of introspection, Bill requires a good coach to keep him in line and occasionally force a bit of reflection. With all of his talents, in the end he drives a very important piece of the strategy: new customer acquisition.

The Doberman is motivated by financial rewards and may respond to significant pay at risk. But with that pay at risk comes substantial upside potential because a Doberman sees himself as a high performer. Many Dobermans glance at their salary, focus on their target incentive, and base their lifestyle on the upside. In addition to pay, Dobermans are equally motivated by a sense of personal accomplishment and recognition by their peers, although most see themselves as peerless. In organizations with good sales compensation plans, it’s not uncommon for a Doberman to make more cash compensation in a given year than his boss or even the president of the company. If he sees his earnings as capped, he’ll probably be prospecting for his next job with an organization that will give him the earnings opportunity.

Retrievers

Retrievers are bred as companions in the hunt. Unlike the Doberman, they don’t prowl unbounded but instead look for opportunities within firing range of the current customer. They are typically responsible for retaining the base of current customer revenue, and more importantly, for finding new growth within the current customer. The Retriever is a watch dog with her eyes keenly focused on her customer domain. When she spots a new opportunity, she’ll bolt after it and bring it home.

The Retriever is constantly alert in pursuit of new opportunities, sometimes to the detriment of protecting the current base of business. While she’s off chasing an opportunity, she still has to keep an eye on the home front or let the Collie stand guard (Collies are discussed in the next section), lest a Doberman from a competitive company steal her customer.

Maria works for a client of ours and sells high-end office furniture to major companies. She is a great cultivator of relationships and an excellent example of a Retriever. She has developed a portfolio of customers over the years that have served her well because she really understands their needs. You’ll most often find Maria in an important customer team meeting or at lunch introducing one of her customers to another. Customers gravitate toward Maria. They confide in her, see her as a member of their team, and reach out to her for advice without fear of being sold. Her typical customer is a raving fan who would proactively call a new customer on Maria’s behalf to make a recommendation—of Maria first and of the company second. If she decides to leave the company, chances are her customers will go with her.

Maria thinks about the customer’s objectives, not just for the near term but over a multiyear term. She’s an account planner, and while she despises filling out those worksheets, she has her own account plan jointly developed with the customer; that plan resides in her head. Her natural talent at building relationships and caring about the customer helps her grow revenue from year to year. But her innate drive keeps her looking for new ways to help the customer and herself rather than resting on the sofa. She’s not a Doberman, however. Ask her to go out and find a new customer, and while willing, she’ll find herself much less effective in that unfamiliar territory.

The Retriever is typically motivated by money and works diligently to hit her quota. With Retrievers, you don’t want to make the incentive out of balance and produce overly aggressive behavior. You want to weight the incentive to make it motivational enough to drive relationship management and development.

Collies

Collies are the ultimate lap dogs and the customer’s best friend. Tony from Philadelphia (introduced at the beginning of this chapter) is a classic Collie. He was bred to stay close to the customer and in doing so learns everything about the customer’s needs. If you’re his customer, he may never leave your side, and over time he may feel like he’s part of your company. Collies are great business retainers because of their depth of customer understanding and level of service.

The downside of all this friendliness is that Collies often lack the perspective to see a new opportunity even if it passes before their noses. When you’re well fed and sitting on a comfy sofa, there’s not a lot of motivation to chase after something new. This dog is prone to the status quo. Tony is so comfortable with his current customers that he’s not thinking much about how to grow the business.

Collies are motivated by the satisfaction of a job well done, although their perception of a hard day’s work and the company’s expectation may be at different levels. Sales compensation for a Collie typically focuses on retaining the business and growing it to a moderate degree. Where the Doberman may have significant pay at risk, the Collie may have a significant percentage of base pay with nominal pay at risk to promote long-term relationship development. The caution on compensating the Collie is to make sure incentives drive behavior and that an abundance of base pay does not diminish his hunger.

Pointers

Pointers, shown in the upper right quadrant of Figure 2-3, source new opportunities. A Pointer may be a new business developer or even an inside salesperson making calls to find prospects. He may roam in new customer territory or scan the familiar field of a current customer. He’s focused on rousting out sales opportunities that may be hiding in plain sight for the team to pursue. While the Pointer may not typically go for the kill, he will pass the opportunity to the nearest Doberman or Retriever to bring it home.

FIGURE 2-3. REVENUE FROM POINTERS AND SERVICE ROLES.

Ray is a Pointer. He spends half his time in a sea of cubicles, headset attached, pacing his 4x6 space while making a rapid series of calls to follow up on the company’s latest marketing campaign. Ray can take a well-designed marketing program and masterfully spin it to capture the customer’s interest and get that all-important first meeting. He’s aggressive; he works the phones, searches out leads, and moves to the next. Mere seconds after he hangs up the phone, another screen of information about the next prospective customer pops up on his computer as the auto-dialer rapidly dials the number. As the phone rings, he scans the screen quickly to understand the company, buyer, and vital characteristics before the prospect answers the call. Between calls, he nurses a can of Red Bull to maintain his pace of pursuit. Ray never stops calling, talking, or searching. Monday he may focus on the financial and banking segment, talking with middle manager buyers about their issues. Wednesday may find him chatting with pharmaceutical executives. The product of Ray’s efforts is usually an abundance of opportunities to be pursued by the organization.

The other half of Ray’s time may be in front of the customer, with a fellow Doberman or Retriever pursuing a lead that he developed. While he may not close that lead, his initial relationship will play a role in ultimately transitioning to the sale.

Ray and his call center of Pointers produce the talent needed to populate a range of field sales roles. Ray, as a young, well-trained Pointer, could become a successful Doberman or Retriever.

Incentives for the Pointer are typically focused on creating opportunities in volume and quality. Depending upon the lead development cycle, incentives for the Pointer may be aggressive or conservative to promote the right behaviors.

Service Dogs

Service Dogs, shown in the center of Figure 2-3, can be sourced from a number of breeds and possess the characteristics of specialization and knowledge in a particular area. The Service Dog works with Dobermans and Retrievers to provide depth on product applications or the needs of a specific industry that are beyond the capabilities of the general seller. This dog may be permitted into places where a regular dog is not because the customer often sees a Service Dog as a personal aide without a hidden sales agenda, engendering the customer’s trust. Like the Collie, the Service Dog runs the risk of growing so aligned with the customer that he becomes indistinguishable from the customer’s organization, and as a result he can sometimes lack the perspective to pursue new opportunities. While the Service Dog may not snatch the bone like a Doberman or Retriever, with his specialized knowledge he can provide the seeing eyes to recognize other opportunities that the customer and other dogs might not recognize.

Roger, a sales engineer, is a typical Service Dog. His childhood friends called Roger a geek, but his technical knowledge married with his ability to understand people has made him a valuable resource for his customers and his company. Roger spends most of his day with his head down, working with the customer’s technical organization or working with his sales organization on proposal development and deal pursuit. Left to his own devices, Roger would likely drift off into solitude and develop the next canine social networking site. But motivated by his team and the right incentives, he has become a critical member of the sales team. While the Doberman or Retriever may be out to dinner with a client or at home with their family on any given evening, Roger will most likely be found in his study on his laptop, connected to the company network, trying to solve a nagging customer technical challenge left over from the day.

Roger is motivated by financial incentives, but like most Service Dogs, it’s the intrinsic reward he receives from his success and the accolades he receives from his team and customers that really drive him.

Sales compensation for the Service Dog is driven by a combination of factors, including whether he holds a unique quota or plays an overlay role with other sales resources. The Service Dog’s incentive will be a significant portion of total compensation if he holds a unique quota, or a smaller portion of total compensation if he has an overlay role with a general rep to motivate him to perform without distracting him from the details of his work.

Hybrid Roles

Hybrids, shown in Figure 2-4, are a blended breed and can be either a deliberate mix or an accident. These dogs typically cover a range of sales strategies and roles from managing current customers to selling new customers, including generating leads, cultivating the opportunity, closing the sale, and assisting with implementation.

One easy way to identify a Hybrid is to look for the most overwhelmed and overscheduled sales reps who are attempting to perform a range of roles beyond their capabilities. In some organizations, Hybrids may be created through selective breeding, but in most organizations they evolve based on demands of the company and constraints in sales capacity. Where the Hybrid may be the jack of all trades, it’s sometimes a deconstructed breed, which often decreases its effectiveness.

Ginger has been with her company for decades. She started when the company was relatively small and she focused mostly on selling to new customers. As she became more successful and the company grew, many of Ginger’s new customers became long-term current customers. As her quota increased each year, she had to continue to find new customers while managing her growing base of current customers. As she balances this role, she struggles with the competing priorities of sales, account management, and service. Ginger’s company sees her as the superstar, but with her stretched workload, she sees herself more as a falling star. Ginger’s associates who grew along with her have either taken on similar levels of work or have left the company for competitors that offer more role clarity and a better quality of life.

Ginger travels from office to customer, her bag bursting with manila files, and tries to manage her busy schedule. But she is increasingly frustrated at not being able to do enough. Her company may soon see the light; the executives are now pondering ideas on how to specialize around customer segments and use more focused selling roles. Hopefully, for the company and for Ginger, the organization will take action before it’s too late.

Like the Hybrid role itself, incentives for this role may try to do all things in one package. Incentives for the Hybrid role are a moderate portion of total compensation and try to include payment for a range of responsibilities, including new customer development and current customer management. If incentives aren’t differentiated between the two, the Hybrid will typically gravitate to her area of greatest comfort. In most cases, high-performing sales organizations eventually move away from these blended roles and toward roles that are more focused and more effective.

The Big Picture on Sales Roles

So how does an assortment of canines impact the sales compensation plan? When it’s working correctly, the compensation plan is a clear reflection of the sales role. That reflection can also be murky, as in the case of Tony. His plan marginally represents his role and drives undesirable behavior. A well-designed sales compensation program clearly outlines the sales role: the types of customers it sells to, the types of products, its priorities, and even the length and complexity of the sales process it follows. In an average set of compensation plans, the sales organization is confused at best and pursues the wrong day-to-day behaviors at worst. If the sales organization incentives misalign with the sales roles, the organization has a problem much larger than sales compensation on its hands.

There are several big-picture considerations regarding talent and sales roles. When considering what breeds of dogs are needed for the business, look at how those roles fit within an overall organizational context. Don’t expect every role to do everything. A role has a certain overall dimension, and it can do only so much. As demands on the role expand, the person in that role becomes less effective, and eventually the organization has to create additional new roles.

We recently worked with a multibillion-dollar company that had 57 sales roles with unique definitions and compensation plans. Each job had its own set of performance measures and mechanics as well. There was an awful lot of inherent complexity, not just in the plans themselves but in the overall system. One job, for example, had five performance measures. With 57 job roles staffed with thousands of reps and unique compensation plans for each role, the company was unable to effectively manage the program. The complexity wasn’t working. The excessive number of jobs came from the evolution of the organization. It had acquired companies and added businesses. In addition, it had two different divisions. One focused on the company’s traditional core products, while the second focused on new technologies. As the company expanded, the jobs grew like the roots and branches of a tree until they were out of control.

Invariably, when a pay period came up, sales operations, human resources, and finance would receive unpleasant surprise messages from the field sales offices like, “We need to pay this new group of 20 people in our account penetration program.”

The sales compensation people would say, “We’ve never heard of this group. What is that job?” The sales operations team would be miffed that they weren’t aware of what their own sales organization was doing. Meanwhile, the finance team would just stew about how incompetent they thought sales was with the budgets. And then they would all have to find money to pay those people. Plan governance was more like plan anarchy.

Usually, there is commonality within jobs. There may be platforms upon which to build a more consistent system. When we looked at the plans within the jobs for this company, we saw a few major job characteristics that made the definition of the jobs and the compensation programs more effective.

The Six Dimensions of Sales Roles

Defining sales roles has a direct connection to the sales compensation plan. When identifying those roles, consider the six dimensions illustrated in Figure 2-5. A sales role (channel or job) is composed of multiple factors that make it effective yet can stretch its capabilities to a point that either maximizes or limits its effectiveness. The factors discussed below must be considered when structuring and managing sales roles. You can use these factors to define sales roles pretty specifically down to what you need for the organization and for the compensation plan.

FIGURE 2-5. SALES ROLES DIMENSIONS.

Sales Strategy Responsibility

This dimension defines the type of customers the organization is targeting. Is the company retaining current customers? Is it penetrating current customers through either product penetration (selling more of the same products) or buyer penetration (getting additional buyers)? Is it pursuing customer acquisition? This combination of possibilities provides overall direction for the job.

Product Responsibility

This dimension describes the products, services, and offers the job will bring to market. Does the rep sell one product, multiple products, or the whole portfolio? The more products each rep is asked to represent, the more his bandwidth is stretched. A product specialist, for example, should be focused and narrow. A rep selling the whole portfolio may need some overlay specialists for support, especially if it’s a complex offering.

Market Segment and Channel Responsibility

This dimension identifies the groups and characteristics of customers for reps who work directly with customers. Market segments can be defined as simply major accounts, key accounts, middle market accounts, and core accounts, or they might be defined by customers, values, or needs. Market segments may also be described vertically, such as healthcare or transportation, or a combination of these variables.

Channel responsibility refers to coverage and management of third party channels. An organization might use distributors, resellers, referral partners, or other types of third party businesses to help get to customers. In that case, it usually uses a role that works with its channel partners. In fact, it may need two roles: a channel acquisition role (someone to go out and acquire those relationships) and a channel management role (somebody to manage, cultivate, and develop those relationships).

Sales Process Responsibility

This dimension refers to the breadth of the sales process the job will span. The sales process may be expansive, covering lead generation, qualification, solution design, proposal development, deal closing, and even implementation. If you ask a salesperson to do all of those things—going from lead generation all the way through the close and the implementation—it stretches his bandwidth. That requires a broad set of skills, as compared to having some jobs that are lead generators or maybe—odd concept—marketing generating an abundance of leads. One role may pick up qualified leads, close them, and turn them over to an implementation specialist. Many organizations oversimplify what’s really required in the sales process.

Marketing, Technical, and Operations Responsibilities

Some jobs have dual responsibilities, performing disparate functions. Some jobs are contaminated with other operations roles and have been cobbled together over time. Moving non-selling roles out of sales to other functions can help clean up the sales job and increase its effectiveness.

Management Responsibility

This dimension identifies roles the job may have in managing other people in addition to selling. The classic jobs affected by management responsibilities are the selling sales manager and the selling branch manager. These combination roles often appear in organizations with emerging management levels. Having a seller straddle both sales and management is sometimes a first step toward pure management jobs that allows the organization to still attach a unique quota to the job and align its cost with a revenue stream. The reality is that sharing a dual selling and management role can create conflicting priorities. A pure management role, effectively defined and staffed, can provide a much greater revenue impact through leadership and development of multiple sellers.

The big concept concerning sales roles dimensions is that the more a job is asked to do, the more stretched it gets and the less effective the job becomes. This customer coverage discipline of job definition is important to understand to make the organization more effective and to have a solid foundation for the compensation program. Once you decide which breeds of dogs your organization needs and clarify their priorities, it’s time to begin compensation plan design.

5 QUESTIONS YOU SHOULD ASK YOUR TEAM ABOUT SALES ROLES

1. Do our roles align with each major revenue growth source without significant gaps or overlaps?

2. Are the sales role dimensions for each job realistic, too broad, or too narrow?

3. Do we have the right breed of talent for those roles?

4. Do we need to develop our talent or source new talent?

5. If we need to make role and coverage adjustments, how should we make that organizational change?