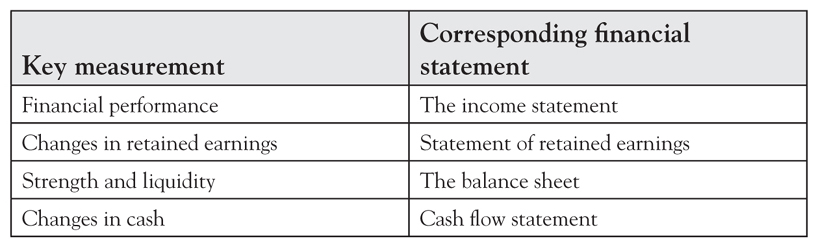

Financial statements represent a prescribed record of the financial conduct of an entity, see below. These are written reports that measure the financial performance, strength, and liquidity of a company. Financial statements also highlight the financial effects of business transactions and events on the entity.

Financial statements provide useful information to a variety of stakeholders:

Managers require financial statements to manage the company by considering its financial performance and position and to make important business decisions.

Stockholders use financial statements to measure the risk and return of their investment in the company and take investment decisions accordingly. They also assess the feasibility of investing in a company. Investors may predict future dividends based on the profits shown in the financial statements. Furthermore, risks associated with the investment may be determined from the financial statements. For example, volatile profits indicate higher risk. Therefore, financial statements provide a foundation for the investment decisions of potential investors.

Financial Lenders (e.g., Banks) use financial statements to decide whether to issue short- or long-term loans to a business. Financial institutions gauge the financial health of a business that allows them to determine the probability of loan turning bad. Any decision to lend should be supported by a satisfactory asset base and liquidity.

Suppliers need financial statements to assess the credit worthiness of a business and decide whether to supply goods on credit. Suppliers need to know if they will be paid. Thus, terms of credit are established according to the assessment of their customers’ financial health.

Customers use financial statements to assess whether a supplier has the resources to guarantee the supply of goods in the future. This is very important where a customer is dependent on a supplier for specialized parts (e.g., monopoly supplier).

Employees use financial statements for assessing the company’s profitability and its consequence on their future pay and job security.

Competitors compare their performance with rival companies to learn and develop strategies to improve their competitiveness and gain competitive advantage.

General Public may be interested in the effects of a company on the economy, environment, and the local community, i.e., Corporate Social Responsibility.

Governments require financial statements to ascertain the validity of tax declarations and quantification of tax receipts. Governments also monitor economic progress through analysis of financial statements of businesses from different sectors of the economy, which will inform government policy.

2.1 Income Statement

An income statement is a report that highlights how much revenue a company earned over a specific time (usually for a year or some portion of a year). An income statement also indicates the costs and expenses that were incurred with earning that revenue. The “bottom line” of the statement usually shows the company’s net income (or profit) or losses. This informs how much the company generated or lost over the period. Thus in summary:

TOTAL REVENUE – TOTAL EXPENSES = NET INCOME

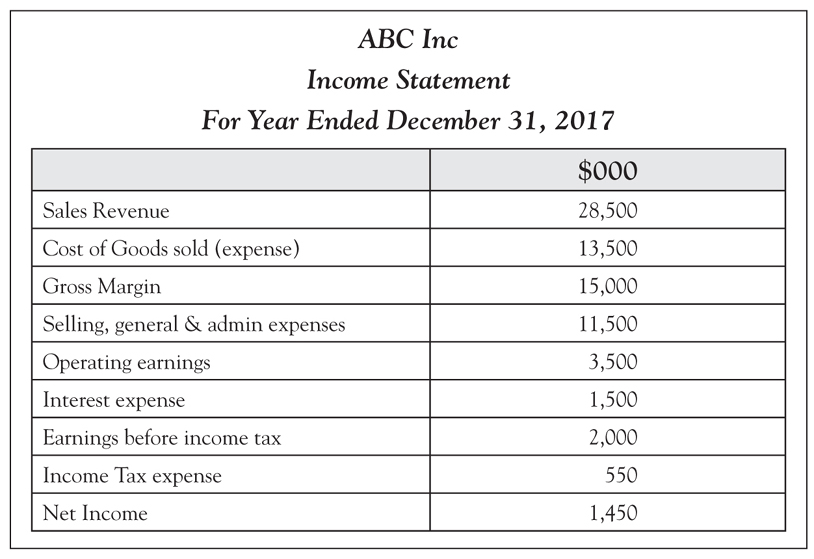

The following figure presents a typical profit report (meaning an income statement) for a medium-sized manufacturing business:

To understand the income statement, referring to ABC Inc., think of it as a set of ladders. You start at the top with the total amount of Revenue generated during the accounting period i.e., $28,500,000. This top line is often called revenue or sales. It is called “gross” because expenses have not been deducted from it yet. Thus, the number is “gross” or unrefined and goes down, one step at a time.

At each step, you make a subtraction for certain costs beginning with Cost of Goods Sold expense i.e., $13,500,000. This number tells you the amount the company spent to produce the goods or services it sold during the accounting period. Resulting in “Gross Profit” or “Gross Margin” i.e., $15,000,000. It is regarded as “gross” because there are certain expenses that have not as yet been deducted from it.

The next section of the income statement deals with operating expenses. These are “Selling, general, & admin’” expenses that support a company’s operations for a given period, i.e., $11,500.000. Operating expenses are different from “Cost of Goods Sold expense,” which were deducted above, because operating expenses cannot be correlated directly to the production of the products or services being sold.

Another important operating expense is depreciation which takes into account the wear and tear on some assets, such as machinery, tools, and furniture, which are used over the long term. Companies spread the cost of these assets over the periods they are used. This process of spreading this cost is called depreciation or amortization.

After all operating expenses have been deducted from gross profit, you arrive at Operating earnings, i.e., $3,500,000, before interest and income tax expenses. This is usually referred as “income from operations.”

Next, companies must account for interest income and interest expense. Interest income is the money companies earn from holding their cash in interest-bearing savings accounts, e.g., money market funds. The interest expense is the money companies pay in interest for the money they borrow. Some income statements show interest income and interest expense separately. Some income statements net off the two numbers. The interest income and expense are then added or subtracted from the operating profits, i.e., $1,500,000, to arrive at Earnings before income tax i.e., $2,000,000.

Finally, at the bottom of the ladder, income tax is deducted, i.e., $550,000, and you discover how much the company actually earned or lost during the accounting period. People often call this “the bottom line,” i.e., $1,450,000.

2.2 Statement of Retained Earnings

A company, or a corporation, at the discretion of its board of directors, can pay some of its income, usually after a profitable period, to stockholders, as dividends and keep the remainder as retained earnings. These are added to the company’s accumulated retained earnings, which appear on the balance sheet under owners’ equity.

After each reporting period, companies produce a statement of retained earnings. This statement emphasizes, firstly, how net income from the current period adds onto retained earnings to the firm’s total retained earnings. This total appears on both the balance sheet and the statement of retained earnings. Secondly, the portion of the period’s Net income the firm pays as dividends to owners of preferred and common stock is shown.

The following is a statement of retained earnings, for ABC Inc.; this includes the earnings of $1,450,000 and cash dividends of $210,000.

Sometimes there may be a situation that causes a company to restrict the distribution of retained earnings. A percentage is set aside that cannot be used as a basis for declaring dividends. This generally occurs when a lender stipulates in a contract that a company does not pay out an exorbitant amount of its retained earnings, to ensure that debt obligations are covered.

2.3 Balance Sheet

The balance sheet is considered as a summary of the firm’s financial position at one point in time. In fact, some firms and most government organizations publish their balance sheets under the alternate name statement of financial position.

In theory, a firm could produce a new and updated balance sheet every day. In practice, they normally do so only periodically, at the end of fiscal quarters and years. The balance sheet heading names a date asserting that “. . . at 31 December 2017.” It is thus a “snapshot” of the firm’s financial position as at that date. The balance sheet therefore differs from other statements, which report activity over a specified time.

In fact, the balance sheet indicates end-of-period balances in the company’s assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity accounts. However, it is important to note its name includes “balance” for another reason. Since, the balance sheets’ three main sections represent the accounting equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ equity

Thus, the term balance applies because the total of the company’s assets must equal (balance) the sum of its liabilities and owner’s equities. This balance is always maintained whether the company’s financial position is good, or indifferent. Double entry principles in accrual accounting guarantee that every change to the total on one side results in an equal, offsetting change on the other side. The balance sheet must balance and will always do so if accounting is carried out correctly.

Assets are what a company uses to operate its business, while its liabilities and equity are two sources that finance these assets. Owners’ equity, also known as stockholders’ or shareholders’ equity in a publicly traded company, is the amount of finance initially invested into the company, including any retained earnings, and it is a source of funding for the business.

The following is a balance sheet for, ABC Inc.

ABC Inc.’s balance sheet is made up of two distinct sections. Assets are stated at the top, and below them are the company’s liabilities and owners’ equity. The assets and liabilities sections of ABC’s balance sheet are ordered by how current the account is. Therefore, in the asset side, the accounts are classified from generally liquid to least liquid. On the liabilities side, the accounts are organized from short to long-term borrowings and other obligations. We will delve deeper into the assets and liabilities.

Types of Assets

Current assets have a useful economic life of one year or less and can be converted easily into cash. Such assets in this class include cash and cash equivalents, accounts receivable, and inventory. Cash, probably the most important current assets, also includes non-restricted bank accounts. Cash equivalents are secure assets that can be readily converted into cash, for example U.S. Treasury Bonds. Accounts receivables consist of the short-term obligations owed to the company by its clients. Companies often sell products or services to customers on credit, thus these obligations are shown in the current assets account until they are honored by the customers. Prepaid expenses are amounts that are paid in advance for future expenses, and as they are used or expire, an expense is increased and prepaid expense is decreased.

Lastly, inventory is the sum of the raw materials, work-in-progress goods, and the company’s finished goods. Depending on the company, the constituency of the inventory account will vary but will typically consist of goods purchased from manufacturers and wholesalers. For example, a manufacturing firm will carry a large amount of raw materials, while a retail firm carries little or none.

Noncurrent assets are assets that cannot be turned into cash easily. They also have an expected life span of more than a year. This can refer to tangible assets such as plant and machinery, buildings, and land. Noncurrent assets can include intangible assets such as goodwill, patents, or copyrights. Intangible assets are not physical in nature, are usually not capitalized, and can make or destroy a company, for example, the value of a brand name, should not be underestimated. Depreciation is calculated and subtracted from tangible assets, which represents the economic cost of the asset over its useful life.

Liabilities

On the bottom of the balance sheet are the liabilities. These are the financial commitments a company owes to external parties. Just like assets, they can be both current and long-term. Current liabilities are the company’s liabilities that will come due, or must be honored, within one year. This includes both shorter-term borrowings, such as accounts payables, together with the current portion of longer-term borrowing, such as the latest interest payment on a multi-year loan. Long-term liabilities are debts and other non-debt financial obligations, which are due more than at least one year from the date of the balance sheet.

Stockholders’ Equity

Shareholders’ equity is the amount of money that was initially invested into a business. If a company decides to reinvest its net earnings into the company (after taxes), these retained earnings will be moved from the income statement onto the balance sheet and into the stockholders or shareholder’s equity account. This account shows a company’s total net worth. As stated earlier for the balance sheet to balance, total assets on one side must to equal total liabilities plus shareholders’ equity on the other.

Complementing the income statement and balance sheet is the cash flow statement, that is a mandatory part of a company’s financial reports since 1987 for publically listed companies. It records the amount of cash and cash equivalents entering and outgoing a company. The cash flow statement allows external stakeholders to understand how a company’s operations are being financed, where its money is coming from and crucially how it is being spent.

The cash flow statement is unique when compared to the income statement and balance sheet as it does not contain the amount of future incoming and outgoing cash that has been recognized on credit. Thus cash is not the same as net income or profit, in the income statement and balance sheet, includes both cash and credit sales.

There are two acceptable methods for reporting a statement of cash flows: the direct and the indirect method. The difference between the two methods is seen in the operating section of the statement of cash flows. Although the total cash provided (used by) operating activities will be the same, the line items used to report the cash flows will be different.

Using the direct method necessitates cash-related daily business operations to be identified by type of activity. For example, cash collected from customers, cash paid to employees, cash paid to suppliers (or paid for merchandize), cash paid for building operations, cash paid for interest, and cash paid for taxes. These types of headings make it easy for users of the cash flow statement to understand where cash came from and on what it was spent.

The FASB prefers the direct method for preparing the statement of cash flows because it gives a better picture of the financial state of the business. However, most companies do not use the direct method, choosing instead the indirect method since it is easier to produce and gives less detailed information to competitors. The indirect method begins with the assumption that net income or profit equals cash and adjusts net income for major non-cash income statement items such as depreciation, amortization, and gains and losses from sales and for net changes in current asset, current liability, and income tax accounts.

The following figures show what the statement of cash flows looks like when both the direct and indirect methods of preparation are used. The following figure is the statement of cash flows using the direct method.

The direct method of preparing the statement of cash flows shows the net cash from operating activities. This section shows all operating cash receipts and payments. Some examples of cash receipts used for by the direct method are cash collected from customers, as well as interest and dividends received by the company. Examples of cash payments are cash paid to workers, other suppliers and interest paid on notes payable and loans.

•Cash received and paid are shown as compared to net income or loss as shown on the income statement.

•Any differences between the direct and indirect method are located in the operating section of the statement of cash flows. The financing and investing sections are the same regardless of which method you use.

Using the Indirect Method

The indirect method starts the operating section with net income (before interest and tax) from the income statement. You then modify net income for any non-cash items such as depreciation from the income statement, see figure follows. Other common items requiring adjustment are gains and losses from the sale of assets. This is because the gains or losses shown on the income statement from the sale will usually not equal the cash a company receives, because the gain or loss is based on the difference between the asset’s net book value, that is cost less accumulated depreciation and the amount the item sold for—not how much cash the buyer hands over to the seller. The following example will demonstrate this further:

Assume a business has a piece of plant it no longer uses because it no longer needs it. The business sells it to another company for $2,500 and the cash received is $2,500, but what is the gain or loss on this disposal? Consider these additional facts:

•The company originally paid $4,000 to purchase the plant.

•The total amount depreciated over time (accumulated depreciation) was $3,000.

•Net book value for the plant on the date of sale was $1,000 ($4,000 cost—$3,000 accumulated depreciation).

The cash received ($2,500) differs from the gain on disposal ($1,500). These are the types of transactions that are reconciled in the statement of cash flows.

The following table summarizes how to account for changes in working capital on the balance sheet in comparison with last year, in the cash flow statement:

Whether using the direct or indirect method, the cash generated from operations in the statement of cash flows should have exactly the same answer. i.e. the ending cash balance should be the same.

2.5 Limitations of Financial Accounting

As discussed earlier, accounting helps users of financial statements to make more informed financial decisions. However, it is important to realize the limitations of accounting and financial reporting when forming those decisions.

Different Accounting Policies and Frameworks

Accounting frameworks such as IFRS allow the preparers of financial statements to utilize accounting policies that most suitably reflect the conditions of their entities.

Whereas a degree of flexibility is important in order to present reliable information of a particular entity, the use of varying accounting policies amongst different entities weakens the extent of comparability between financial statements.

The use of different accounting frameworks (e.g., IFRS, U.S. GAAP) by entities operating in different geographic locations presents challenges when comparing their financial statements. The problem is being addressed by the rising use of IFRS and the convergence process between leading accounting bodies to create a single set of coherent global standards.

Accounting requires the use of estimates in the preparation of financial statements where accurate amounts cannot be established. By their very nature, estimates are intrinsically subjective and thus lack accuracy as they involve the use of management’s insight in establishing values included in the financial statements. Where estimates are not founded on objective and verifiable information, they can dampen the reliability of accounting information.

Professional Judgment

The use of professional judgment by the preparers of financial statements is necessary in applying accounting policies in a way that is coherent with the economic reality of an entity’s transactions. However, differences in the interpretation of the demands of accounting standards and their application to real-life scenarios will always be inevitable. Therefore, the greater the use of judgment involved, the more subjective financial statements will be.

Verifiability

Audit is the major mechanism that allows users to place trust in financial statements. However, audit only offers reasonable but not absolute assurance on the truth and fairness of the financial statements. Consequently undertaking an audit according to acceptable audit standards still means that certain material misstatements in financial statements may yet remain undetected due to the inherent limitations of the audit.

Use of Historical Cost

Historical cost or the Historical Cost Convention is the most widely used basis for the measurement of assets. On the other hand, the use of historical cost poses various problems for the users of financial statements as it does not account for the change in price levels of assets over a period of time. This diminishes the relevance of accounting information by presenting assets at amounts that may be far less or more than their realizable value and also fails to account for the opportunity cost of using those assets.

The effect of the use of the historical cost basis is demonstrated by the following example.

Company ONE purchased plant for $100,000 on January 1, 2013 which had a useful life of 10 years.

Company TWO purchased similar plant for $200,000 on December 31, 2017.

Depreciation is charged on a straight-line basis.

At the end of the reporting period at December 31, 2017, the balance sheet of Company TWO would show a fixed asset of $200,000 whilst Company ONE’s financial statement would show an asset of $50,000 ($100,000 – $100,000/10 x 5 years) (net of depreciation).

The above example presents an accounting inconsistency. Even though the plant presented in company ONE’s financial statements is competent of producing economic benefits worth 50% ($100,000/$200,000) of Company TWO’s asset, it is carried at a historical cost equivalent of just 25% ($50,000/$200,000) of its value.

In addition, the depreciation charged in Company ONE’s financial statements (i.e., $10,000 ($100,000/10) p.a.) does not reflect the opportunity cost of the plant’s use (i.e., $20,000 ($200,000/10) p.a.). Therefore, over the asset’s life, an amount of $100,000 would be charged as depreciation in Company ONE’s financial statements even though the cost of maintaining the productive capacity of its asset would have significantly increased. If Company ONE were to distribute all profits as dividends, it would not have enough funds to replace its existing plant at the end of its useful life. Therefore, the use of historical cost may potentially result in reporting understated profits, which means that the business is not sustainable in the long-run.

Due to the problems inherent with the use of historical cost, some preparers of financial statements use the “revaluation model” to account for long-term assets. However, due to the restricted market of various assets and the cost of periodic valuations required under revaluation model, it is not widely used in practice.

An important development in accounting is the use of “capital maintenance” in the determination of profit that is sustainable after taking into account the resources that would be required to “maintain” the productivity of operations. However, this accounting basis is still in its early stages of development.

Measurability

Accounting only takes into account transactions that are capable of being measured in monetary terms. Therefore, financial statements do not account for those resources and transactions whose value cannot be reasonably assigned such as the dedication of the workforce.

Limited Predictive Value

Financial statements are based on the Historical Cost Convention consequently they present an account of the past performance of an entity. They offer little insight into the future of an entity and subsequently lack any predictive value which is vital from the point of view of investors.

Fraud and Error

Financial statements are highly at risk to fraud and errors which can undermine the overall credibility and reliability of information contained in them. Intentional manipulation of financial statements that gravitate toward achieving predetermined results (also known as “window dressing”) has been a regrettable reality in the recent past as has been popularized by major accounting debacles such as the Enron or WorldCom scandal.

Cost–Benefit Compromise

Reliability of accounting information is related to the cost of its production. Hence, there may be times when the cost of producing reliable information offsets the benefit expected to be gained which suggests why, in some cases, the quality of accounting information might be flawed.

Having briefly discussed the limitations of financial accounting, it is important to note that standard setters do their best to issue guidance in the form of accounting standards to dampen these problems. Advanced accounting courses cover accounting standards in depth. Finally, it is important to remember that all human endeavors are flawed but it is necessary to remain vigilant and ethical at all times during your accounting studies and career.