Change is the law of life. And those who look only to the past or present are certain to miss the future.

—John F. Kennedy

Every organization—whether commercial or nonprofit, start-up or well-established—will, sooner or later, have to deal with changes to its internal or external circumstances. In this chapter, we take a trip into nature to understand why it is so important to be able to adapt to change. You can also read about organizations that experienced major changes, with fatal consequences.

2.1 A (R)evolutionary Idea from an Amateur Biologist

A sailing ship drops anchor in the bay of a beautiful island. A moment later, its dinghy is carrying a young man to the shore. After four long and hard years, sharing a small cabin with a captain suffering from melancholy and fits of rage, he is looking forward to the prospect, once more, of heading out alone.

The young man answers to the name Charles Darwin and 26 years earlier was born in Shrewsbury, a quiet village in the West Midlands of England. His mother—who dies when Charles is eightcomes from the rich Wedgwood family, makers of the famous porcelain. His father, a prosperous physician who sees Charles as his successor, is terribly disappointed when, at the age of sixteen, he abruptly stops his medical studies because he cannot stand the sight of blood. After another failure, this time studying law, he finally sees a chance to graduate in theology at Cambridge, with a boring life in a rural parish as his future. But his great passion is biology.

When in the spring of 1831, he gets the offer to sail on the research ship HMS Beagle, he does not have to think for long. The captain, Robert FitzRoy, is looking for a dinner companion because, in his position, he may only invite “gentlemen” and his favorite companion has cancelled at the last minute. FitzRoy, an extremely strange man, chooses Darwin partly because of the shape of his nose, which, to FitzRoy, indicates a strong character. That Darwin was trained as a cleric adds to FitzRoy’s conviction. FitzRoy’s official mission is, indeed, to map the coastal waters, but his hobby is to look for evidence for the biblical interpretation of creation. On departing from Plymouth, on December 27th, 1831, he could never have suspected that this expedition would result in evidence precisely to the contrary.

It’s September 17th, 1835 when Darwin sets foot ashore in Chatham, the easternmost island of the Galapagos archipelago, about 800 kilometers off the coast of Ecuador. During the ensuing five weeks, he collects from the group of islands a huge collection of specimens of the local flora and fauna, including many different types of finches. Darwin was not yet an accomplished naturalist, so a few obvious observations completely elude him at the time. Being inexperienced he also forgets to document from which islands the birds come. It will take another two years, after returning, to sort out this mess completely.

Coping

Darwin’s friend John Gould, an ornithologist, notices, in 1837, that in addition to their obvious similarities, the finches also have very different beaks. Together, they then determine thirteen different species, and assume that the beak of each species is adapted to the local food sources of their respective island. Their conclusion is that the birds were not created this way, but they have, in some way, changed themselves. This was probably pretty bad news for the creationist FitzRoy.

Six years after returning, Darwin finally begins to work out his new theory in a manuscript. In 1844, he lays it aside as the book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation appears. It suggests that man might well have evolved from lower primates, without help from the Divine Creator. There is a tremendous uproar and the anonymous author is cursed from the pulpits. (For that reason, the author waited forty years before he dared to let his name be known; it turned out to be Robert Chambers, the largest bible publisher in the world). Darwin decided to devote himself to raising ten children and writing a rather-thick tome about barnacles (which, understandably, he later hated) that kept him busy for eight years. He also became a kind of recluse, barely able to work because he was suffering from the debilitating effects of Chagas disease, which he contracted in South America as a result of an insect bite.

A Controversial Theory

Darwin’s manuscript would probably have been lost if he had not received a request, in 1858, from Alfred Russell Wallace to comment on his essay. This essay bore strong similarities to Darwin’s manuscript. Darwin then decided that they had to present their theory jointly to the Linnaean Society. Wallace lost interest and, from then on, would refer to this theory as ‘‘Darwinism.”

Finally, toward the end of 1859, On the Origin of Species is published, in which Darwin presents his theory. It is an immediate commercial success, although there is much criticism in the early years about there being only limited evidence. However, in 1865, the Czech monk Gregor Mendel, published evidence of a mechanism that explained how, according to Darwin, all living things are descended from a single common source. Nevertheless, Darwin’s theory was not widely accepted until 1930. During his later life, Darwin was frequently honored by the scientific community, but never for his evolutionary theory.1

By the way, Darwin never used the phrase survival of the fittest; it is taken from the book Principles of Biology, written by Herbert Spender in 1864. The term evolution was first used by Darwin in 1872, in the sixth edition of his book. But what was in his first edition is the now famous phrase:

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent; but the one most adaptable to change.

This phrase summarizes very strongly what Darwin understood. That the animal kingdom is all about one thing: adaptivity. According to him, the ability of species to adapt to (changing) circumstances is the most important condition to survive natural selection.

You will probably wonder what this trip to the wonderful world of flora and fauna has to do with your organization? More than you think. Let’s go on an expedition into the world of organizations and find out.

2.2 From Organisms to Organizations: The Extinction of Technology Companies

What is the brand of your current mobile phone? The probability is now very small that it is a Nokia. But have you ever had a Nokia phone in the past? Probably the answer is affirmative. Strange, is it not? You’ll soon see what is the logical explanation for this.

Many, including perhaps yourself, seem inclined to think that the biggest companies will always win, meaning that well-known brand names would exist forever. But, if you look at the stock market listings on Wall Street over the past fifty years, you’ll make a surprising discovery. What do titans like Kodak, Polaroid, Chrysler, GM, Saab, Rover, Pan Am, RCA, Compaq, Atari, MGM, and Texaco have in common? They needed state aid, or had to be taken over, have been decimated, were consigned to the margins, or have gone bankrupt. Let’s look at a few of these examples.

Eastman Kodak

Founded in 1888 by George Eastman, Kodak hits its peak about a century later. The company then had over 145,000 employees worldwide, generating more than $16 billion in annual sales and was valued at approximately $30 billion. It is so ubiquitous that even its slogan is found in most dictionaries: a Kodak moment. Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon, used Kodak film when he made his famous recordings. More than eighty films that have won an Oscar for best film were made with Kodak film. Kodak was a stock market icon on Wall Street, an example of the American Dream. But then two things happened. First, Fuji entered the US market and brought a smart marketing approach that rapidly grew their market share to 17 percent. Second, Kodak decided to hold fire on digital photography (Kodak had already invented the first digital camera in 1975 and registered 1,100 patents, but chose not to put the camera into production because it would harm its film business). Only at the beginning of the new millennium, as film revenues collapsed, was it given any priority. For several years, Kodak then benefitted, thanks to aggressive marketing, from the rapid and profitable growth in sales of digital cameras.

But, the company does not anticipate that these cameras will quickly become commodities, or that this, together with the arrival of newcomers from Asia, will force prices down, creating negative margins for Kodak. Market share falls from 27 percent to 7 percent and the losses build up fast. In 2012, the company files for bankruptcy, making a $1.3 billion dollar loss on annual revenues of $4.1 billion. After selling almost all its patents, Kodak is now trying to survive as a supplier of printing products in the enterprise market. As Steve Ballamy put it in 2015: “We were a bankrupt company three years ago, and now we’re kind of a start-up. But we’re like the most mature start-up in the history of business.” Current market capitalization hovers around $660 million, around 2 percent of its peak value. Let’s just hope that your pension fund has not invested in Kodak.

Nokia and Others

Or take another giant, Nokia. It was founded in 1865 to make rubber overshoes. Around 1980, they decided to deploy a bold diversification strategy by focusing on a new product in the emerging market of mobile phones. This makes the company extremely successful. Between 1998 and 2012, Nokia is the world leader in this market, selling, in 2005, its billionth phone. At its height, Nokia has sales of $37 billion, employs 132,000 workers and has a market capitalization of $251 billion.

Although rumors are rife in 2002, it’s not until January 2007 that Nokia has its deus ex machine moment: the totally unexpected introduction by Apple of the iPhone (see Figure 2.1). Samsung responds almost immediately with its F700. Nokia’s leadership sees this as a disruptive innovation because they think they are way ahead in the field of hardware and software (Nokia even already have a successful smartphone, the Communicator, but not one with a touchscreen and apps). Grown lethargic and cumbersome via many years of success, Nokia’s time-to-market for innovations from the R&D labs is much too long. Due to conservative internal forces, the company is not sufficiently open to change. When a member of the Board of Directors takes the new iPhone home one evening, his four-year daughter begins immediately to play with it. When, after a while, she asks him if she can put the “magic” phone under her pillow, he realizes that his company has a huge problem.2

Figure 2.1 The market capitalization of Nokia and its direct competitors: after the collapse of the “Internet bubble” in 2000, the demise of Nokia becomes final in 2007; Sony is also struggling despite the success of its PlayStation (Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream)

Toward the end of 2008, Nokia finally introduces its first touchscreen phone, the 5800 XpressMusic. However, this just does not function well. Moreover, Apple and Google have been a lot smarter than Nokia, working with app developers. Mobile-app programming is easier, apps offer increased revenues, and both offer a central download store (App Store and Android Market). Until 2010, Nokia’s smartphone sales continue to grow, but the overall market is growing many times faster. Despite hefty price cuts, sales collapse. Although the company still sells a lot of classical phones, intense competition and the associated price erosion of 60 percent eat too much of its margin. In 2013, Nokia is technically bankrupt and is forced to sell its Mobile Division and related patents to Microsoft for only $7.4 billion (who then decided to totally discontinue the Nokia brand in November 2016). The crown jewels for a pittance, because Nokia simply did not have the necessary resilience. And probably no one at Nokia was rejoicing at the prospect of making rubber wellys again.

Research In Motion, the manufacturer of BlackBerry, had a similar experience. This company trusted blindly that its large installed base, its own network, and its superior security capabilities would allow it to continue to dominate the market. As a result, Research In Motion was too slow in adapting to changes in the market and its market share fell, between 2010 and 2016, from 41 percent to 1 percent. Its market capitalization is now about one-twentieth of at its peak.

Even successful dotcom pioneer Yahoo! proved vulnerable. It was founded in 1994 and became an immensely popular web portal, with a market cap of about 110 billion dollars in 1999. But when the Internet grew, a search engine became a necessary tool for Internet users. Yahoo! decided not to build its own, but to use the search engine of start-up Google, thus helping its own rival become a dominant player. In later years, the company experienced trouble in finding the right strategic focus, resulting in 24 different mission statements during its lifetime. This also inhibited a successful acquisition policy. In 2002 Yahoo! was offered the opportunity to buy Google for 1 billion dollars and in 2006 to buy Facebook for 1.1 billion dollars, but declined in both cases. It did buy companies like Flickr, GeoCities, Delicious, and Tumblr, but these all quietly faded away. In 2008, it received a take-over bid of 44.6 billion dollars from Microsoft, but did not accept it. In recent years, Yahoo has tried to position itself as a broad media company, but it really missed out on the growth of mobile Internet, partly by refusing to build its own browser or operating system. In July 2016, Yahoo! was forced to sell all of its Internet activities to Verizon Communications. As they will rebrand these activities as Altaba, this means the end of an illustrious company.3

When Kodak and Nokia were at their heights, who would have dared predict the total collapse of the absolute market leaders? Pretty much anyone who did would have been declared insane. But both could not adapt enough or quickly, could not cope with changing circumstances. But this happens not only to large, established companies. As you’ll see below, it also applies to start-ups.

Iridium

In 1991, Motorola and a global partnership of eighteen companies decided to build a mobile phone system that could be used anywhere in the world. Literally anywhere. From the glaciers of Antarctica to a ship in the middle of the ocean; the peaks of the Himalayas to the heart of the African jungle. They dared to think big. No less than $5.2 billion was invested in an arsenal of fifteen rockets from the United States, China, and Russia. These were needed to put a fleet of 72 satellites into orbit, 781 kilometers above the earth’s surface. Seven years after the company was founded, all the satellites were, at last, in orbit and the first call was made. And not quite nine months later, the company went into receivership.

What went wrong exactly? In 1991, there was no complete global coverage for mobile phones and the available coverage was also expensive and unreliable. On this basis, Iridium made several assumptions about the needs of potential customers, what would be appropriate products and services, and of course potential earnings. But in the seven years it took to bring their product to market, innovation in mobile phones and mobile networks developed incredibly fast. Coverage had become much better, call rates had reduced significantly, and the first data applications were already available. In addition, the phones themselves had become much smaller, while those of Iridium were about the size and weight of a brick (an old military field telephone had nothing on these). Even worse, the Iridium telephone could not be used in a building or car, because it needed a line-of-sight connection to a satellite—not exactly practical. A conversation with a regular cell phone cost (in 1998) about 50 cents per minute and with an Iridium phone 7 dollars. The purchase price of the device itself was over $3,000. So, day-by-day, Iridium’s target customer segment shrank, until there remained just one, very small, niche market. Looking on the bright side, however, at least Iridium didn’t have to invest in an expensive CRM system.

Incidentally, Iridium is once more alive and kicking. In 2000, an investment group bought the total Iridium Estate for $25 million; its “real” value was around $6 billion. In 2011, with an adapted business model, the new company welcomed its 500,000th customer.4

How It Can Also Be

Happily, despite the dramatic example of Iridium, new businesses are continuously being created, and becoming successful. Think of online start-ups: names like Alibaba, Amazon, Facebook, Google, WhatsApp, Instagram, Snapchat, Spotify, Zappos, Uber, and Zalando. And other companies such as Tesla, Dyson, GoPro, Intel, ASML, Dell, TomTom, Ikea, Swatch, easyJet, Smart, Cirque du Soleil, and Oculus Rift. And there are large established companies that have been forced to reinvent themselves and have done so quite successfully. LEGO, Marks & Spencer, Burberry, Mini, Apple, and Club Med all did so. Of all these companies, you could say that they are sufficiently adaptive, because they saw changes and then took action.

But would you dare to bet your savings against them still existing in 25 years? And what might the future look like for nonprofit organizations such as hospitals, Chambers of Commerce, museums, charities, water boards, pension funds, unions, and municipalities? Interesting food for thought perhaps?

2.3 Future-Proofing: Agility Required

The parallel between organisms and organizations is evident. In Darwin’s terms, organizations such as Kodak, Nokia, and Iridium have not survived natural selection. They are extinct, just like the mammoth, the cave bear, or saber-toothed tiger. Various case studies indicate that this mainly has to do with a lack of adaptivity. Not surprising when you consider the increasing speed in which their environments developed. We also see, for example, that the number of patent applications, the annual number of shares traded, and the volumes of data used by companies also show exponential growth curves since circa 1980.5 Can we recognize these patterns in other organizations? That’s what we are going to look at now.

There are many well-known examples of companies that have existed for more than a century: Ford, Harley-Davidson, DuPont, 3M, Siemens, General Electric, Heineken, and Philips (in 2006, after almost 1,400 years in business, the oldest company in the world closed down: the Japanese temple-builder Kongo Kumi). However, these companies are the exception, not the rule. There is tremendous dynamism in the creation, growth, shrinking, and disappearing of companies.

Let’s first look at emergence and disappearance, the coming and going of businesses. According to The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) statistics on their 28 member countries, the period from 1998 to 2015 was somewhat cyclical, seeing the economy both grow and contract. In this period, an increasing number of businesses were established annually (including 26 percent being subsidiaries of existing companies), with an average yearly growth of nearly 6 percent. However, the number of businesses that closed (including 9 percent bankruptcies) also increased, with an average yearly growth of over 5 percent. Ultimately, the numbers show that, overall, there is growth, but when we look at company size, the picture is far more nuanced. The number of businesses with 50 or more employees has decreased by over 5 percent, and those with 2 to 49 employees have remained relatively constant; the number with just one employee (the self-employed) grew by 29 percent. The average life expectancy of a new business, at present, has risen to about six years, with 66 percent closing down within their first six years of existence.6

Just look for a moment at the battlefield of retail where, in recent years, the traditional players had no response to the rapid rise of e-commerce and other changes. For example, Blockbuster, Circuit City, RadioShack, Dixons, Woolworths, Ritz, Tower Records, Comet, Borders, Athena, Tie Rack, Zavvi, Austin Reed, BHS, Thirst Quench, Dewhurst, and American Apparel all went bankrupt. (And for how long will a store like Barnes & Noble still exist, not to mention small players like independent local stores).

Growth and Shrinkage

Now, let’s look at the growth and shrinkage of the financial turnover of companies. Since 1955, Fortune magazine has been publishing its ranking of the largest US companies, based on revenue, the Fortune 500. Studying the rankings over longer periods provides some interesting insights. For example, in these sixty years, only four companies have been top more than once: General Motors (37 times), ExxonMobil (ten times), Wal-Mart (four times), and Shell Oil (the American branch of Shell) twice. But what about the durability of the other companies on the list?

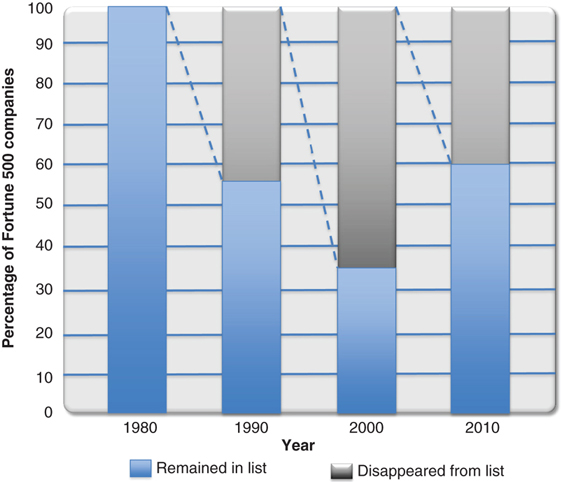

Here, too, it is very dynamic. As Figure 2.2 shows, every ten years, on average, about half of the companies fall out of the list. This is due to shrinkage in the turnover of these companies, and increased turnover of companies, which were previously outside the Fortune 500.7 Other research confirms this: of the companies in the Fortune 500 list of 1955, only 12.2 percent were still in the list in 2014.8 Babson Olin even expects that, in the next decade, 40 percent of existing Fortune 500 companies will not survive, while Yale estimates that the average lifespan of S&P 500 companies has decreased to fifteen years, from sixty to -seven years in the 1920s.9

Figure 2.2 On average, around half of the companies fall out of the Fortune 500 within ten years

That the turnover of large companies rises and falls is clear. But what about smaller companies? Dartmouth researched all 29,688 companies listed on US stock markets from 1960 to 2009 in 10-year cohorts and concluded that longevity is decreasing. Companies that listed before 1970 had a 92 percent chance of surviving the next five years, whereas companies that listed from 2000 to 2009 had only a 63 percent chance, even when controlled for the dotcom bust and multiple periods of recession.10 The World Bank noted that in the period 2006 to 2014, more companies suffered a decline in sales and the number of fast-growing companies fell. That seems logical, given the prolonged economic crisis. But how does the picture look over a longer period? To determine this, US scientists used the renowned Compustat database and looked at turnover and profitability in the period 1980 to 2012, a period in which there were frequent, and strong changes in market conditions.

They discovered a very clear, established pattern of performance:

- 18 percent of companies outperformed their industry average 80 percent or more of the time;

- 13 percent of companies underperformed compared to their industry average 80 percent or more of the time;

- 69 percent of companies exhibited erratic periods of over- and underperformance within their industry.

Most companies, therefore, perform very erratically or relatively poorly. The number of companies able to sustain good performance for a long time is limited. And only a few companies managed to improve themselves, during the measurement period, from erratic to long-term overperformers.

Adjustment Potential

Does this dynamic of development, growing, shrinking, and disappearance of firms tell us something about the extent to which companies are able to adapt to their circumstances? According to the researchers, that is indeed the case. They found overperformers possess the skills to adapt quickly to their environment, to see and react earlier than their competitors, exploiting opportunities and responding quickly to threats. Other research also shows that 61 percent of the fast-growing companies, at least once, radically changed course. For example, by jumping into an emerging market or creating a new business model. In short, it is all about agility.

By now, you’ll have the suspicion that the success of your organization might well depend on the manner in which your organization works with future changes in its circumstances. Therefore, in the following section you can find out more about the causes and impact of these changes.

By reading this chapter, you’ll have discovered the following:

• Scientific research has shown that only those animals and plants that can adapt to changing circumstances survive.

• This adaptivity is required in order to avoid extinction, and applies not only to organisms, but also to organizations. Kodak, Nokia, and Iridium are negative examples of this concept.

• There is a lot of momentum in the creation, growth, shrinking, and disappearance of companies. Scientific research shows that the best-performing organizations are agile, allowing them to adapt quickly to change.

References

1. Bryson, B. (2003). A Short History of Nearly Everything. New York: Random House.

2. Wokke, A. (2014). A Goodbye to Nokia; Goodbye to a Former Leader. Tweakers.

3. Cohen, R. (2017). Yahoo Article. FD.

4. Blank, S., and B. Dorf. (2012). The Startup Owner Manual. K & S Ranch Press.

5. Kotter, J. (2014). Accelerate. Brighton: Harvard Business Review Press.

6. Stat Line–CBS.

7. Worley, C. G., T. Williams, and E. D. Lawler. (2014). The Agility Factor. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

8. Perry, M. J. (2014). Fortune 500 Firms in 1955 vs. 2014; 88% are Gone, and We’re All Better off Because of that Dynamic “Creative Destruction.” AEI blog.

9. Ismail, S., S. M. Malone, and Y. van Geest. (2014). Exponential Organizations. New York: Diversion Publishing.

10. Govindarajan, V., and A. Srivastava. (2016). “The Scary Truth about Corporate Survival.” Harvard Business Review, December issue, pp. 24–25.