The Essence of Agile Management

The only way to win is to learn faster than anyone else.

—Eric Ries

Based on the previous chapters we now know the relevance of agile management and its genesis. In this chapter we define what agile management is and on what principles agile management should be based.

7.1 Agile Management as an Integrated Approach

As you already saw in section 3.1, higher levels of VUCA (the volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity of markets) require similar levels of agility. And because the VUCA level appears to be on the rise in most sectors, achieving agility should be relevant to most organizations. This applies equally to public authorities, nonprofit organizations, and commercial enterprises. As Gary Hamel once put it: “The only reliable advantage is a superior capacity to reinvent your business model before circumstances force you to do so.”1 No surprise then, that Jack Welch, the famous CEO of General Electric between 1981 and 2001, had the motto: “Change before you have to.”

General Electric

Let us remain, for a moment, with the example of General Electric (GE). Like many companies, in the early nineties GE decides to transfer production to low-wage countries, in their case predominantly China. Between 2000 and 2012, however, wages increase by a factor of five. At the same time, the price of oil goes up by three times, significantly increasing transportation costs. This fundamentally changes the business case for offshoring. The problem is that GE no longer have the necessary knowledge and experience to go back to building its own products, this expertise is now the domain of its foreign contractors.

But in 2012, GE turns this disadvantage into an advantage: the company can start with a clean slate to design new production processes. Close by the head office, GE opens a small factory making refrigerators and stoves and employs new engineers and production workers. They discover that these products can be offered for a retail price that is approximately 20 percent lower than the Chinese versions. The success factor appears to be that GE’s production workers now operate in an open, collegial and self-critical environment working directly with designers, engineers, marketers, and others in the production chain.

Even more important than cost reductions is the shortening of the product development cycle. This is made possible by having production and other functions work together in the same physical place. Shortening this cycle is necessary in order to keep up with the accelerating pace of product innovation, as household products no longer have a market lifetime of seven years, but just two or three. As a result, the plant has become a laboratory for innovation, which is able to adapt itself to changing customer needs and competitive environments.

Delivery times also come down significantly: instead of the five-week transit time from the Chinese factory to retailers in the United States, it is now one day (and even just thirty minutes to local stores). This enables GE to react quickly and adapt to changes in customer demand and production. Thus, GE massively reduces inventory costs. Also, they now rarely need to discount models that have become obsolete as a result of competitors bringing new and improved models to market. Very tangible results from agility.2

McDonald’s

Something similar is happening at McDonald’s. As a global fast-food brand serving 68 million customers daily, this organization is always under the critical lens of public opinion. Since its founding, in 1940, it has had to adapt regularly to changing requirements often brought about by changes in social perceptions. They have had to respond to paradigm shifts in issues such as health, nutrition, animal welfare, the environment, and working conditions. In the past decade, for example, a clear trend emerged as a demand for healthy food and quality coffee. Good espresso made Starbucks into a major new competitor for McDonald’s.

As McDonald’s notices that these developments are becoming more frequent and occurring faster, it is just a small step up from their lean way of working to move to agile management. Via frequent experimentation, McDonald’s is able to accelerate renewal of its restaurants and products. It applies a process cycle of try–listen–refine. New ideas are tried small; if something does not work, McDonald’s stops immediately, and if something is a success, they roll it out to all their restaurants as quickly as possible.

A concrete example is the use of touch screens to place and pay for orders. Or pilots for products or processes that occur in selected branches. In some stores, they tested allowing people to create their own burger. And in certain branches, they investigated how customers respond to concepts such as the McCafé and the Salad Bar. In still other restaurants, they’ve experimented with table service, or expanding the breakfast range. This encourages the perception that McDonald’s is stronger than the competition in customer choice and experience. It continues to innovate, currently by testing smartphone ordering and payment. It’s clear McDonald’s values and prioritizes agility.

Agility

But what do we actually mean by agility? Agile literally translates as “the ability to move quickly and easily.” In the context of this book, it is expressed by terms such as dexterity, flexibility, lightness, speed, sharpness, strength, focus, precision, and adaptability. The aim of agility is adaptivity, the responsive capacity of the organization to adapt to new requirements: to be ready for anything.

Compare it with a chameleon. These insect-eating reptiles are a very successful survivor, existing for over one hundred million years. Its success is partly due to its two independently moving eyes, with which he constantly scans the environment for food and danger. And, depending on the situation, he can, with lightning speed, adapt the color of his skin: sometimes as camouflage and sometimes to stand out, in order to scare enemies away or to find a mating partner. He has also developed an amazing tongue for catching prey: is the fastest functioning muscle in any reptile or mammal (for comparison, the 0–60 mph time of a chameleon’s tongue is 1/100th of a second).3

If you want your organization to be as effective as a chameleon, you need to have resilience and flexibility. And, because you’ve got to minimize time-to-market, an undeniable need for speed. Not just in the island of a single team, but across the entire value chain. Any weak links will hugely slow down the whole enterprise.

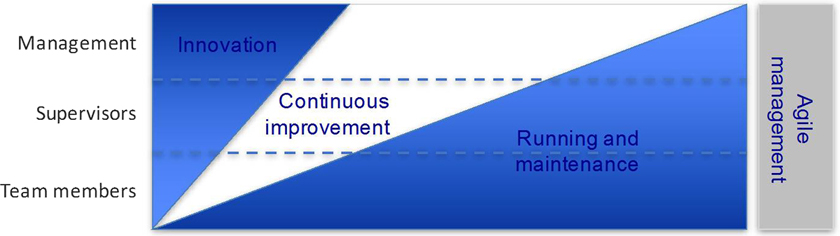

The agile management process is meant to ensure the agility that makes the necessary adaptability achievable. It is actually a combination of agile and lean, we could call it agilean. As can be seen in Figure 7.1, agile management forms the integrated, facilitative basis for:

Figure 7.1 Agile management facilitates all business processes (based on Imai4)

- Maintenance–These are the activities of the organization aimed at maintaining current technological, managerial, and operational standards, for example via training and discipline. Maintenance is the responsibility of everyone in the organization. The rule of thumb is that the organization must spend about half its time on this.

- Continuous improvement–The activities intended to enhance technological, managerial, and operational standards, over the longer term, through small, daily steps. This, too, is a responsibility of everyone in the organization. About one-third of the organization’s time should be spent here.

- Innovation–Defined here as dramatic improvements in the short term, due to relatively large and targeted investment, and is the responsibility of middle and top management. This occupies about one-sixth of the organization’s time.

In this way, agile management is the basis for both operational activities and projects, as you will see later in the Spotify and ING case studies. It is aimed at both internal and external customers.

7.2 For Internal and External Customers

It is very important to understand that agile management applies not only to external customers, but also to internal customers. Obviously, the external customer is central in agile management: the one who pays everyone’s salaries. Everything within the organization, therefore, should be aimed at creating maximum added value for the external customer. And that is exactly why the internal customer is relevant, as you can see in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2 Porter’s value-chain model shows how customer value is created

The interplay of internal processes ensures the organization, as a whole, can create added value for the external customer. The better these internal processes are aligned, the more-effectively and efficiently the organization creates added value for the external customer. This means that departments that are not directly customer-facing do indeed serve a customer: the internal. Each internal customer is the next step in the value-creation cycle. The output of a process conducted by one department becomes the input for the next process, either in the same or a different department. And thus, one process is always the customer of the preceding process. The better these internal customers are served, the more value is created for the end (external) customer. It is, therefore, important that work activities focus on both internal and external customers. Excellent tools for ensuring this takes place are value-stream mapping and the business-model canvas, as we shall see in Chapter 10.

But what is the relevance of agile management for departments with internal customers? It is found in the logic of the “domino effect” (see Figure 7.3). If changes occur in the behavior of the customer or the market, the customer-facing departments of the organization will notice it first. Sales and customer service would be forced to adapt their methods the most quickly, with consequences for the departments of which they are internal customers. These internal departments must quickly adapt their processes to meet the new requirements of sales and customer service, and so on.

Figure 7.3 The domino-effect of changing requirements

Agile management is not an all-or-nothing choice. Although full implementation is of course the ideal situation, it is perfectly possible to choose a customized hybrid model where some departments use it while others continue to work in the traditional way. The latter are usually very small or responsible for mostly simple, repetitive tasks with fixed outcomes (which can be optimized through “lean” methods). Nor is the form of implementation cast in concrete. Above a certain minimum level, it is a flexible model. This means during experimentation, each organization will discover what best suits it. In other words, you can apply an agile management approach to implementing agile management.

In short, every employee, to a greater or lesser extent, will be involved in agile management. The next section discusses the principles that should be followed.

7.3 The Eight Principles of Agile Management

Agile management is an iterative, incremental way of working that creates a responsive organization. Iterative means that work is done in systematic, repeatable, process steps, accepting that sometimes a step needs to be done again, because insight has identified that it began with a false premise. Incremental means that only a little is added to what already exists, whether that is a product or an insight. As we saw in section 6.1, the principle of building on what is available can be found in the foundations of science. Isaac Newton once said: “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

The goal is not explicitly to achieve a large, radical leap forward in one go. Of course this sometimes happens, because you accidentally discover something fundamentally new. However, the starting point is that, together, many quick, small steps add up to a big leap forward, but with much less initial risk and uncertainty. This idea is based on eight key principles, which we discuss below.

- Creating value

The highest priority is value for customers through rapid and continuous delivery of new or renewed products and services. These are working solutions that offer relevant experience. This applies for both internal and external customers.

- Creating value for the customer means working “lean”; therefore any activity the customer is not willing to pay for must be eliminated. To avoid unnecessary investments and long lead times, work aims to produce so-called minimum viable products; these allow the customer to experience the essence of the benefits of a product or service.

- Understanding the customer

In order to create value for internal or external customers, it is necessary to understand their requirements, needs, and behaviors.

- The customers completely self-determine the relevance and value of the experiences and solutions offered. It is impossible to do so on the basis of internal assumptions. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the wishes, needs, and the behaviors of the target group. These can be examined with the aid of voice-of-the-customer tools as feedback sources.

- Alignment

Creating value for the customer requires that the customer is given a central position in the close collaboration of a team that comprises stakeholders from all relevant departments. This team should be motivated and should share a common vision of success.

- Much of the value-creation is lost if the client experience is chopped up into separate soloed departments. Therefore, a multidisciplinary internal collaboration, around customers and their behavior, is necessary and this should be sponsored at the highest organizational level. The team members must be convinced of the usefulness of the overarching objectives that transcend the interests of their own departments. And if several multidisciplinary teams are involved, agreement must also be made, between those teams, to coordinate their goals and activities.

- Empowerment

The team should get all the support and autonomy it needs, removing any external obstacles and giving it the full trust and mandate to do the job independently. This gives the team end-to-end responsibility for achieving its goals. Daring to trust each other increases the speed of collaboration.

- Management’s main role is to facilitate teams. This includes resolving issues that go beyond the team level, so the team can focus entirely on its tasks. Checking on assignments only “before and after,” empowers the team and its leaders, allowing them full freedom to carry out their work in a self-organizing way. Micro-management is thus counterproductive.

- Synchronous and visual communication

The most efficient and effective way to share information with or within the team is via synchronous communication-preferably face-to-face.5 And to make everything as visual as possible.

- Teams operate best when team members can communicate quickly and directly with each other. This means that the ideal working environment consists of a shared space where all team members are physically together. The space should also have a visual overview of all relevant activities, including a prioritized schedule that team members briefly update to each other at the start of each day.

- Learning by experimenting

The most important measure of progress is learning via a structured cycle, and this requires accurate measurement. Experimentation and failure form an important part of learning, and should therefore be unanimously accepted.

- The focus is on continuous improvement, requiring a structured process in which experimenting is central. To generate maximum learning, working with hypotheses, SMART goals, precise measurements, analyses, and evaluations is strictly necessary. In addition, all stakeholders must feel safe to dare to make mistakes, because these are a calculated risk.

- Speed and flexibility

Change should be considered as a source of opportunity. This is taken into account in the planning and in the focus on simplicity and quality, because the ability to respond quickly to changes is a source of competitive advantage.

- To test ideas as quickly and cheaply as possible, and with the help of the 80/20 rule, work is managed using “sketches” instead of thick, rigid plans. And by deploying short-cycles with small, incremental additions to products, services, and experiences. These additions should, as simply as possible, show the essence, omitting anything unnecessary. Additions and changes are picked up, at a constant pace, from the ideas pipeline and delivered within a few weeks, which makes for flexibility. The work is then checked continuously against the agreed minimum quality levels.

- Accountability

The team activities should be accountable. After each iteration, the team honestly evaluates all its activities and results, adjusting its plans and activities accordingly.

- The team also has a meta-goal, to learn as much as possible about its own functioning. Therefore, team members ensure transparency in their work and they periodically review the added value it is generating. Where necessary, the team optimizes its approach so that return-on-effort continuously improves.

Figure 7.4 shows that these eight principles form the core values of agile management.

As you will see later in this book, an extensive toolbox is available of methods and concepts to apply agile management principles in the daily practice of your organization. But, naturally, it all begins with culture and leadership. You can read more about this in the next section.

Figure 7.4 The eight principles of agile management

7.4 Culture and Leadership: Working Together Differently

Often you hear managers complain: Why don’t my employees take the initiative more often? Why do they seem not really concerned? Why don’t they show entrepreneurship? Why is their motivation so low? And so on.

What these executives are often unaware of is that, unconsciously, they are maintaining the situation themselves.6 It is a self-fulfilling prophecy. As we saw in chapter 3, managers increasingly focus on the short term, on efficiency and predictability. They seek stability in order to achieve the results promised to stakeholders. Surprises are thereby not appreciated. That’s why they want to hold onto the security that traditional hierarchical structures and processes provide, which are mostly product-oriented instead of customer-oriented. They fall into the trap of directly controlling their employees, determining, top-down, what their people must do and how they must do it. They do not dare to trust their employees (see the YouTube video The smell of the place for a brilliant illustration).

The consequence is that employees dutifully perform what is asked of them. They become passive and do not feel “ownership.” Leaders see that progress does not go fast enough or well enough to get the necessary results, so they start to get themselves involved. They take the employees chair and begin working with content and details. They’re micro-managing.

This has the consequence that employees become uncertain, afraid to make mistakes, and do not dare to take responsibility. Their motivation disappears, resulting in, for example, slowness, errors, and defensive behaviors. Often a political atmosphere develops: there is tension with and between the managers, who reflexively lapse deeper into old patterns. They become even more hands-on, take the initiative away from their employees while plaguing them with inspections and monitoring. And the result? Even more bureaucracy.

The selective perception of executives confirms their original starting point: the need to focus on the short term, on efficiency and predictability. Now, as Figure 7.5 shows, they are all in a vicious circle.

Figure 7.5 The vicious circle of directive control

From Directive to Servant Leadership

What we see, in the above situation, is a negative spiral. But how do we break through it? And might it even be possible to create a virtuous circle? Organizations that work with agile management have, indeed, shown that you can. These organizations opt for a bottom-up approach. Within the framework of their mission, vision, and strategy, they try to incentivize employee entrepreneurship as far as possible. A culture of “do first, and ask (permission or offer apologies) afterwards”; the art of letting go. They achieve this by creating self-organizing teams (for some inspiration see the YouTube video Greatness by David Marquet). That means freedom, but does not mean a lack of commitment. Delivering operating results is central. Teams and team members are given responsibility to achieve their results, but the way they do so is entirely their own choice. So there is room for initiative and entrepreneurship. This ensures high levels of motivation and productivity and improves customer service.

This means a lot for managers. First, this method usually leads to a flattening of the organizational structure: hierarchical management layers can thus be eliminated, making many executive posts redundant. Second, leadership style changes from directing to serving (as Robert Greenleaf already put it in 1904: “Good leaders must first become good servants”). The main task of management becomes to facilitate teams, as much as possible, to deliver performance. For example, by ensuring they have optimal working conditions, protecting them from less relevant and urgent issues, and so on. An important task is to motivate the team and give them confidence, encourage them to get the best out of themselves and develop themselves. Thirdly, it means that many executives become “working foremen.” In addition to their management tasks, they also collaborate as a team member and carry out practical work. So, as it were, managers need to reinvent themselves.

Perhaps the greatest challenge lies in the combination of autonomy and alignment. In other words, how to realize maximum freedom for the teams and, at the same time, facilitate the necessary coordination between the teams and the strategy needed to ensure certain things do not happen—or are not duplicated. Many executives feel this as a sort of simple balance: an either/or situation. Nevertheless, it does not have to be so. Just as the leadership communicates very clearly what are the strategy, goals, and structures and how this relates to each team, they create, within the teams, a lot of freedom to go their own way. Good fences make good neighbors, as the saying goes. That is how you realize autonomy and alignment. And alignment is easier when there is greater visual representation of the work (you can read more about this in Section 11.2).

A good example of the issues above can be found at Patagonia and at Buurtzorg (what Frederic Laloux calls “teal” organizations7). But also in the Spotify story, which follows below.

7.5 Culture and Leadership within Spotify

The Swedish company Spotify was established in 2006. By now, about 100 million people in 58 countries use the music-streaming service, of which 40 million have a paid subscription. For its library of over 30 million songs, Spotify has paid a total of approximately $3 billion to the copyright holders. The most popular song to date, One Dance, has been streamed more than one billion times (for the top-50 songs this is 30 billion in total). Spotify is also a formidable competitor to iTunes, as we’ll see in section 10.1.

Spotify now has approximately 1,900 employees in eighteen countries. In all these countries, the organization has adopted agile management. Spotify puts a particular emphasis on its culture. The organization promotes its culture by making it the focus for its agile coaches during week-long Spotify culture bootcamps for new employees and by encouraging active storytelling through presentations, blogs, and so on. The ethos of the Spotify culture is interesting to examine. Below it is discussed according to Spotify’s own explanation.8

Principles are More Important than Rules

Spotify begins with the belief that rules are a good starting point, but not more than that. If necessary, rules may be broken or changed. This happened partly because Spotify noticed that the rules associated with its Scrum and Kanban approaches increasingly began to “pinch,” to hinder rather than help as the organization grew. It now labels these rules as optional. Spotify prefers the principles of agile management over the strict procedures and rules defined within the Scrum approach (probably the remark most frequently made by Spotify employees is “It depends . . .”). Spotify has also flexibly adapted the role of Scrum Master. Instead of monitoring the quality of the process, this person focuses on facilitating and coaching the team. They call this role the Agile Coach.

Empowerment via Smart Alignment

Spotify works in teams of up to eight people, with end-to-end responsibility to fulfil their specific purpose. The goal could be, for example, improving the infrastructure or a particular feature. The team is fully autonomous in achieving its goal, and works within a few frameworks such as Spotify’s overall mission and strategy, and with associated short-term goals that are determined each quarter. Each team has its own fixed workplace. All the offices are in one room; the side and rear walls are large whiteboards where things can be worked out visually. The front wall, on the corridor side, is made up entirely of glass in order to stimulate transparency and accessibility. Adjacent is an open lounge space for dialogue, and, behind it, a small space (the huddle room) a quiet space for working on something individually or with only one or two team members.

Autonomy helps to increase team spirit and motivation and avoids unnecessary meetings or discussions. At the same time, Spotify wants to prevent suboptimization. Spotify calls this principle “loosely coupled but tightly aligned.” The better the alignment between the teams around their goals, the more autonomy they create for their implementation work. In addition, it helps to pursue small, frequent improvements. This ensures routine and speed and prevents the need for intensive consultation and collaboration between teams on large, complex improvement projects. Spotify calls it decoupled releases.

At the highest level within the organization, the leadership must therefore communicate clearly to the team what improvements should be realized (or problems solved) and why. A team must then work together to find the best solution themselves.

Trust Instead of Control

Due to the high degree of autonomy within Spotify, there is little standardization in the way they work. Each team may choose his own methods. The company relies on the effect of cross-pollination and assumes that the methods that work best will spread themselves through informal consultations between the teams, and become a de facto standard. In this way, Spotify tries to find a healthy balance between consistency and flexibility. Teams may also work on each other’s products in a kind of open-source model, what one might call self-service. They do not have to wait for each other, quality improves and knowledge is disseminated.

Spotify wants to be more liberal than authoritative, and it accepts the risk of everything falling into chaos. If everyone dares to trust each other’s good intentions, Spotify will benefit much from reduced bureaucratic control. Teams must, therefore, simply behave according to good citizenship. Spotify also wants to avoid becoming a “political” organization. Decisions, as much as possible, are based on data rather than opinions or authority.

Respect and Motivation

Spotify tries to build their organization around the human being. The company wants employees to get energy from working with their colleagues. This involves mutual respect, and big egos are undesirable. Employees should get recognition for their successes. Wanting to help each other well and quickly is paramount. Spotify also actively tries to keep employee motivation as high as possible, so has discontinued project-time estimates and time registration. For example, Spotify uses “guilds”; these are platforms for special interests in which employees can voluntarily take part in the form of events and forums. Spotify wants to build “communities” where employees feel a sense of belonging, because it does not really believe in the value of organizational structures. Also, every employee gets 10 percent hack time to work on its own ideas and projects.

Experimenting, Failing, and Learning

Spotify’s basic belief is that it wants to fail as soon as possible, and thereby learn and improve quickly. Teams and employees should have no fear of failure. Spotify doesn’t want to prevent failures, but does want to be able to recover from them quickly. Mistakes and failures are displayed on fail walls and extensively discussed in the team’s retrospective discussions. Not to establish whose fault it was, but to see what everyone can learn from it and what needs to be changed. Continuous improvement is central.

The decoupled releases, we encountered earlier, ensure failures always have a limited impact on the customer and they are quickly recovered. Spotify calls this the limited blast radius. Also releases are rolled-out in steps to small groups of customers and are closely monitored in order to intervene quickly if something goes wrong.

To encourage further learning, Spotify also uses the Lean Startup approach in its own experimental cycle think it-build it-ship it-tweak it. Here, one works with hypotheses, minimum viable products, and A/B testing analysis. Innovation and impact are more important than predictability and reliable planning. Constantly trying out new things is not only for products, but also for their own methods and processes. Many teams use a “kata-board” (borrowed from Lean) in which they describe the current problems and desired future state. They also describe the next step toward that situation and the three key activities that go with it.

Finally, you just heard about hack time. Twice a year Spotify even has a Hack Week where everyone works together on their own fun ideas. Everything is permitted and regularly, useful applications emerge from this activity. The week ends with a demo day and a big party.

By reading this chapter, you’ll have discovered the following:

• Agile management is an integrated approach to maintenance, continuous improvement, and innovation. It is aimed at both internal and external customers.

• Agile management is an iterative, incremental way of working that makes an organization responsive. It is based on eight principles: creating value; understanding the customer; alignment; empowerment; synchronous and visual communications; learning by experimenting; speed and flexibility; accountability.

• Agile management breaks the vicious circle of sending directives. Using self-organizing teams stimulates entrepreneurship. This challenges traditionally minded executives to reimagine their own roles.

• The Spotify case shows how such an interpretation of culture and leadership can be successful.

You have now come to the end of Part 1 of this book. In Part 2, you can discover the methods and tools currently available to concretely implement agile management within your organization.

1. Hamel, G., and L. Välinkangas. (2003). The Quest for Resilience. Brighton: Harvard Business Review, pp. 52–63.

2. Setili, A. (2014). The Agility Advantage. Jossey-Bass.

3. Anderson, C. V. (2016). Off Like a Shot: Scaling or Ballistic Tongue Projection Reveals Extremely High Performance in Small Chameleons. Nature—Scientific Reports. http://www.nature.com/articles/srep18625, (January 6, 2016).

4. Imai, M. (2012). Gemba Kaizen. New York: McGraw-Hill.

5. Carpenter, C. E., and S. N. Madhavapeddi. (2008). Perceptions of Organizational Media Richness: Channel Expansion Effects for Electronic and Traditional Media across Richness Dimensions. Professional Communication 51, no. 1, pp. 18-32.

6. Ardon, A. (2011). Break the circle! Publisher Business Contact.

7. Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations. Millis: Nelson Parker.

8. Thanks to Henrik Kniberg; see also the two YouTube videos about the “Spotify engineering culture.” (Also on the corporate culture of Zappos.com example can be found on YouTube inspiring videos.)