Overview

At the heart of the Somali conflict is a struggle between the federal government and the insurgency presently known as al-Shabaab. The latter had inherited the legacy of the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC), a system of Islamist rule that restored order in Mogadishu in the mid-2000s after a decade-long civil war. International suspicion that the UIC was in the grip of al-Qaeda led to an invasion by neighbouring Ethiopia in 2006, supported by the United States. The UIC collapsed, but its enforcement wing regrouped and joined other militia groups to form al-Shabaab in 2006. A Transitional Federal Government (TFG) was established in 2004, until a constitutionally backed federal government assumed power in 2012. Yet its weak legitimacy and reliance on foreign patrons have hampered its ability to fight the insurgents.

After more than a decade of civil war, al-Shabaab is far from defeated. In 2020, attacks claimed by al-Shabaab targeted government figures and army posts across the country and spilled over to neighbouring Kenya, where militants raided a military base housing Kenyan and US troops. The group retained control over large swathes of central and southern Somalia and continued raising estimated revenues that match those of the country’s authorities.1 Even amid the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, al-Shabaab was reported to provide a superior degree of governance and security for the population than the federal government. Authorised in 2007, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) continued to support the ill-equipped Somali National Army (SNA) in counter-insurgency efforts. However, maintaining control remained a challenge: AMISOM and SNA troops are thinly stretched across the territory, so once they withdraw to their operating bases from retaken areas, al-Shabaab rapidly re-enters the territory to reestablish control.

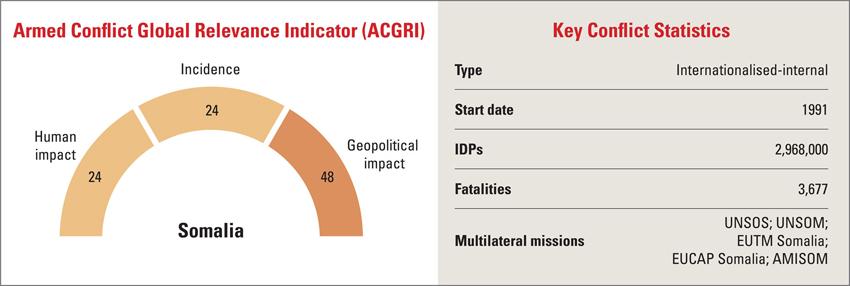

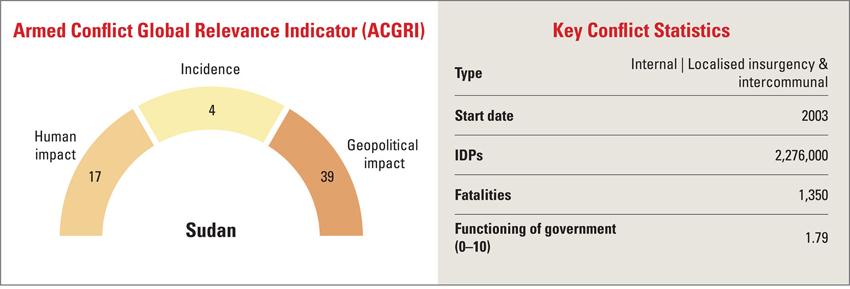

ACGRI pillars: IISS calculation based on multiple sources for 2020 and January/February 2021 (scale 0–100). See Notes on Methodology and Data Appendix for further details on Key Conflict Statistics.

Additionally, disputes between the Somali government and the federal member states (Galmudug, Hirshabelle, Jubaland, Puntland and South West, plus the de facto independent Somaliland) continued to undermine the functioning of the political system. Struggles over government interference in local elections and the allocation of powers and resources escalated in the run-up to the parliamentary elections, initially scheduled for December 2020 but with a new date yet to be set at the time of writing. Opposition leaders accused Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, popularly known as ‘Farmaajo’, of delaying the elections to seek political gains, and ceased to recognise his authority after his constitutional term expired in February 2021. Against a backdrop of protracted political crisis and armed conflict, Somalia continued to be plagued by chronically weak institutions, widespread poverty and low human-development measures, as well as by environmental factors that drive land degradation and exacerbate communal conflict and displacement.

Conflict Parties

Somali National Army (SNA)

Strength: 19,800 personnel. 3,000 additional troops under the Puntland government and an unspecified number of militias.

Areas of operation: Galmudug, Hirshabelle, Jubaland, Puntland and South West (excluding self-declared independent Somaliland).

Leadership: General Odawaa Yusuf Rageh (army chief of staff).

Structure: The SNA is divided into four command divisions and spread across Somalia’s operational sectors. It has associated special-forces units such as the US-trained Danaab.

History: Efforts to build the SNA began in 2008. After two decades of state collapse, the SNA had to be built through both new recruitment and the incorporation of existing armed actors such as clan militias. These efforts were challenged by the lack of coordination among international partners, internecine clan fighting and the ongoing al-Shabaab insurgency. As a result, the SNA continues to suffer from deep-seated internal cleavages and cohesion problems.

Objectives: Secure the territorial authority of the federal government of Somalia, primarily through the defeat of al-Shabaab.

Opponents: Al-Shabaab, the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) in Somalia, militias and criminal actors.

Affiliates/allies: AMISOM, the European Union, Turkey, the United Kingdom, US.

Resources/capabilities: The SNA suffers from severe shortages of resources – particularly of small arms – amid widespread internal corruption, which sees soldiers selling their arms (including to al-Shabaab) to make up for irregular and low salaries.

Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen (al-Shabaab)

Strength: Active fighting force of an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 militants, not including fighters’ families, networks and those living in their controlled areas.2

Areas of operation: Strongest in southern Somalia (Jubaland, Hirshabelle and South West). Presence is more limited in Galmudug and Puntland. No full control over any areas of Mogadishu, but the city’s northern peripheries and economic hotspots (e.g., Bakara Market) are subject to al-Shabaab authority.

Leadership: Ahmad Umar Diriye, better known as Abu Ubaidah, is the current leader, or emir.

Structure: A consultative council (majlis al-shura) is the group’s central decision-making body, although regional political and military authorities enjoy considerable autonomy. Al-Shabaab’s military wing is divided into six regional fighting units. An intelligence wing with a transnational reach (Amniyat) oversees a large security apparatus through which the group curtails dissent and maintains internal cohesion.

History: Emerged in December 2006 after breaking away from the UIC, which had offered little resistance against the Ethiopian invasion of Somalia. Over more than a decade later, al-Shabaab has evolved into a highly effective insurgent group, which appeals to nationalist sentiments to boost recruitment and can challenge the authority of the federal government.

Objectives: Defeat the federal government and establish Islamist rule in Somalia.

Opponents: Federal government, SNA and ISIS Somalia.

Affiliates/allies: Opportunistic alliances with militias and organised-crime syndicates.

Resources/capabilities: Al-Shabaab has benefitted from access to several sources of income, including checkpoint taxation, extortion, kidnappings, illicit trade, revenues from piracy and funding from transnational Islamist groups.

ISIS Somalia

Strength: Between 250 and 300 fighters.

Areas of operation: Based in the Galgala mountain region of Puntland, but periodically conducts targeted attacks in Bosaso and Mogadishu.

Leadership: Believed to be led by Abd al-Qadir Mumin, who was reported killed in an airstrike in March 2019. Later video footage, however, suggests he is still alive and remains leader.3

Structure: Little is known about its internal structure but given the group’s small size and the regular targeting of senior figures by both Somali and US forces, it is likely to be relatively decentralised.

History: Mumin broke away from al-Shabaab with a small group of fighters in October 2015 and pledged allegiance to ISIS. Al-Shabaab has vowed to eliminate the rival group.

Objectives: Expand its influence by spreading ISIS’s ideology within Somalia and neighbouring countries, such as Ethiopia, and attract broader support.

Opponents: Al-Shabaab, Somali and Puntland security forces.

Affiliates/allies: Believed to have connections with other Islamic State affiliates in Yemen and, more recently, Central Africa.

Resources/capabilities: Small arms.

African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM)

Strength: 19,626 troops.4

Areas of operation: The five troop-contributing countries (TCCs) are Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. Their forces are each responsible for a sector in central and southern Somalia, including Banadir and Lower Shabelle (Uganda), Lower and Middle Juba (Kenya), Bay, Bakool and Gedo (Ethiopia), Hiiraan and Galguduud (Djibouti), and Middle Shabelle (Burundi).

Leadership: Burundian Lieutenant General Diomede Ndegeya (force commander), appointed in August 2020. Yet there is no centralised command-and-control structure, which makes coordinating operations difficult. Each sector’s forces operate under their own command and are ultimately responsible to their own governments.

Structure: AMISOM contingents function as conventional militaries.

History: The UN authorised the African Union to deploy a peacekeeping mission in February 2007 to support the TFG. The mission had a six-month mandate and was allowed to use force only in self-defence. In the following years, the situation failed to stabilise, and the UN agreed to boost AMISOM troops and extend the mission’s mandate and scope.

Objectives: Defeat al-Shabaab, retake its territory and protect the federal government of Somalia.

Opponents: Al-Shabaab.

Affiliates/allies: Supported by numerous international governments and periodically by military contingents from allied countries, which deliver training, including the EU, Turkey, the UK and the US.

Resources/capabilities: Lacks critical resources such as air assets, but its key challenge is the unpredictability of donor funding, which makes strategic planning difficult.

The United States

Strength: Approximately 700 troops, mostly redeployed to military bases in neighbouring Kenya and Djibouti.5

Areas of operation: Details of ground operations rarely disclosed. Drone strikes predominantly target areas of central and southern Somalia controlled by al-Shabaab.

Leadership: US Africa Command (AFRICOM) oversees most military operations in Somalia. General Stephen J. Townsend (AFRICOM commander); Major-General Lapthe Flora (head of the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa).

Structure: US troops in Somalia operate under AFRICOM’s component commands. These include US Army Africa, the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa, Joint Special Operations Command and a Mogadishu-based Military Coordination Cell tasked with coordinating operations between US forces and AMISOM.

History: The US began targeting al-Shabaab in January 2007 under president George W. Bush, with military operations significantly expanding during the Obama administration. In November 2020, president Donald Trump announced a plan to withdraw ground troops from Somalia, which became effective in January 2021.

Objectives: Defeat al-Shabaab as part of the US war on terror and support the federal government of Somalia in retaking territory.

Opponents: Al-Shabaab.

Affiliates/allies: The federal government of Somalia, AMISOM and the UN.

Resources/capabilities: MQ-9 Reaper drones are commonly used to conduct airstrikes in Somalia. US troops have also provided military advice and training to AMISOM and Somali military forces, especially the elite Danaab Brigade of the SNA.

Conflict Drivers

Political

Weak state capacity and limited governance:

Plagued by years of conflict, the federal government suffers from poor political legitimacy, widespread corruption and weak institutions. Above all, its longstanding inability to provide security and public services has prevented the government from exercising its authority outside Mogadishu. Rural Somalis rarely interact with representatives of the state other than the SNA, which has a poor reputation among the population. Meanwhile, al-Shabaab’s hold over rural southern Somalia allows the group to provide basic services, including justice mechanisms and Koranic education.

Clan politicisation:

Somali clans challenge all political structures designed to transcend their authority. In fact, the politicisation of clan identities has contributed to the initiation of violent conflicts in Somalia. Clan loyalties can fracture political arrangements or beget unstable, exclusionary relationships, while clan competition inhibits the development of a functioning political system. Competition among Somalia’s four major clans – Darod, Dir, Hawiye and Rahanweyn – is regulated through a ‘4.5’ power-sharing system, which stipulates that political appointments are divided equally among the clans and the myriad sub-clans. However, rather than fostering clan inclusion, the system has reinforced and politicised clan identities.

Economic and social

Increasing appeal of Islamist ideology:

The spread of violent Islamist ideology was also key to the rise of al-Shabaab. Amid the collapse of state institutions and weak rule of law, Islamist groups succeeded in responding to popular grievances over justice and socio-economic inequalities. Lately, al-Shabaab has incorporated nationalist tones about global jihad into its propaganda, in an attempt to widen its appeal among the general Somali population.

Environmental factors:

Environmental factors play a major role in exacerbating conflict in Somalia through land degradation and extreme weather conditions. Rainfall seasons are shortening and becoming increasingly unpredictable, with floods and droughts undermining the livelihoods of rural communities. Communal conflicts over scarce resources, such as water and fertile land, are increasingly common, particularly between farmers and herders, and overlap with clan and sub-clan dynamics. Environmental pressures have contributed to significant refugee outflow during the last decade and to rural-to-urban forced migration into Mogadishu and Baidoa. Food insecurity is also pervasive.

International

Regional and wider influences:

International involvement in Somalia has undoubtedly helped contain al-Shabaab’s insurgency, but has also stoked domestic tensions. Ethiopia and Kenya have long been involved in Somalia’s domestic affairs, providing political and financial assistance to allied Somali elites and intervening in cross-border clan conflicts. Notably, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have increasingly engaged in security and financial operations in Somalia, where their support for clan and local militia groups has exacerbated tensions between the centre and the periphery. Additionally, the large Somali diaspora exercises disproportionate influence in the country’s politics through its considerable private capital and investment. Members of the diaspora have occasionally channelled resources to clans and other armed groups, including al-Shabaab.

Political and Military Developments

Growing tensions between the federal government and the federal states

Relations between the Somali central government and the federal member states remained strained in 2020, with unresolved disputes over the holding of the parliamentary elections and the succession to President Farmaajo. Ahead of the parliamentary elections initially scheduled for December 2020, a proposal to move away from indirect voting stoked tensions between Farmaajo and the opposition, including the presidents of Puntland and Jubaland. In February, federal meddling in the Galmudug local elections triggered clashes with Ahlu Sunna Wal Jamaa (ASWJ), a Sufi group whose militants were integrated into Galmudug’s security forces after battling with al-Shabaab. Jubaland President Ahmed Madobe, backed by Kenya and a vocal critic of Farmaajo, threatened to annul parliamentary elections if the federal government did not withdraw its troops from Gedo region ahead of the vote.

Fears that Farmaajo would delay the vote and abuse his presidential prerogatives to remain in power after the end of his term drew criticism from the opposition. In July, the Somali parliament ousted prime minister Hassan Ali Khayre, who was at odds with the president over the latter’s intention to delay the ballot. Despite reaching a consensus to keep the indirect voting system in September, the parliamentary elections were postponed to February 2021, with the Somali election body citing concerns over security and the coronavirus pandemic. After Farmaajo’s term expired in February 2021 without a clear electoral time frame, opposition candidates ceased recognising the president and called for a peaceful transfer of power.

Al-Shabaab's insurgency

Al-Shabaab confirmed its ability to launch highprofile attacks against government targets. Suicide bombers killed the governors of Nugaal and Mudug provinces in March and May respectively, while an explosion in December 2020 targeted the newly appointed Prime Minister Mohamed Hussein Roble. Other attacks were directed at military targets, including the Army Chief of Staff General Odawaa Yusuf Rageh, who survived a vehicleborne improvised explosive device (VBIED) attack in Mogadishu’s Hodan district.

Al-Shabaab regularly attacked SNA and AMISOM military bases, convoys and patrols in rural areas across central and southern Somalia. In the early months of 2020, an increase in mortar attacks on Mogadishu revealed the difficulty facing security forces in expelling al-Shabaab from the areas surrounding the capital and the nearby Afgoye district. Al-Shabaab has increasingly shifted its operations northwards since ASWJ’s demise; in Puntland, it launched hit-and-run attacks on military posts and assassinated several security personnel, politicians and civil servants. As much as 25% of Somali territory is estimated to be under the control of al-Shabaab, which collected an estimated US$13 million through extortion and taxes in 2020 alone.6 Al-Shabaab also confirmed its significant transnational reach. In January 2020, the group staged an attack on Manda airstrip in Camp Simba, a military base situated in Kenya’s Lamu County that houses US and Kenyan troops.

Developments in counter-insurgency operations

During 2020, AMISOM and US forces continued to provide critical assistance to the SNA in its fight against al-Shabaab. Despite the withdrawal of some US special forces from Somalia, an estimated 72 counter-terrorism operations – 54 of which have been confirmed by AFRICOM – were conducted on Somali soil, the second-highest number since the first reported strikes in 2007.7 AMISOM supported Somali troops in the battle of Janaale, which they recaptured from al-Shabaab in March 2020. In May, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) passed Resolution 2520, which confirmed the deployment of 19,626 personnel until February 2021, stating that ‘the situation in Somalia continues to constitute a threat to international peace and security’.8 Yet a drawdown of 1,000 troops in February 2020, and the additional withdrawal of 200 Ethiopian troops in November 2020, foreshadowed the planned transfer of security responsibilities from AMISOM to the SNA at the end of 2021. Additionally, Somalia’s diplomatic turbulences with Djibouti and Kenya injected further instability into AMISOM.

Key Events in 2020–21

POLITICAL EVENTS

20 February 2020

Farmaajo signs the new electoral bill to end indirect voting into law, triggering protests from the opposition.

18 March

Somalia’s federal government introduces a ban on international flights, two days after confirming the country’s first COVID-19 case.

29 May

The UNSC passes Resolution 2520 confirming the deployment of AMISOM troops until February 2021.

25 July

Somalia’s federal parliament passes a motion of no confidence against prime minister Hassan Ali Khayre.

20 August

Somalia’s political leaders agree on adopting indirect voting in the upcoming parliamentary elections.

23 September

The Somali parliament unanimously confirms the appointment of Mohamed Hussein Roble as prime minister.

1 December

A deadline to hold parliamentary elections is missed.

15 December

Somalia cuts diplomatic ties with Kenya, accusing its neighbour of interfering in its domestic affairs.

8 February 2021

Opposition leaders announce they no longer recognise President Farmaajo.

MILITARY/VIOLENT EVENTS

8 February 2020

Clashes between the SNA and Jubaland security forces take place in Beled Hawo, Gedo region.

27 February

Dozens are killed in heavy clashes between the SNA and ASWJ fighters in Galmudug.

29 March

The governor of Nugaal province is killed in an al-Shabaab suicide attack in Garowe.

17 May

An al-Shabaab suicide bomber kills the governor of Mudug province and three bodyguards in Galkayo.

13 July

Army General Odawaa Yusuf Rageh survives a suicide carbomb attack in Mogadishu’s Hodan district.

16 August

Al-Shabaab attacks an upscale hotel in Mogadishu, killing at least 16 people.

18 November

Hundreds of Ethiopian peacekeepers from Tigray region are disarmed over security concerns.

18 December

Al-Shabaab claims responsibility for a suicide attack targeting Somali Prime Minister Mohamed Hussein Roble in Galkayo.

18 February 2021

Government forces and opposition supporters clash in Mogadishu.

Impact

Human rights and humanitarian

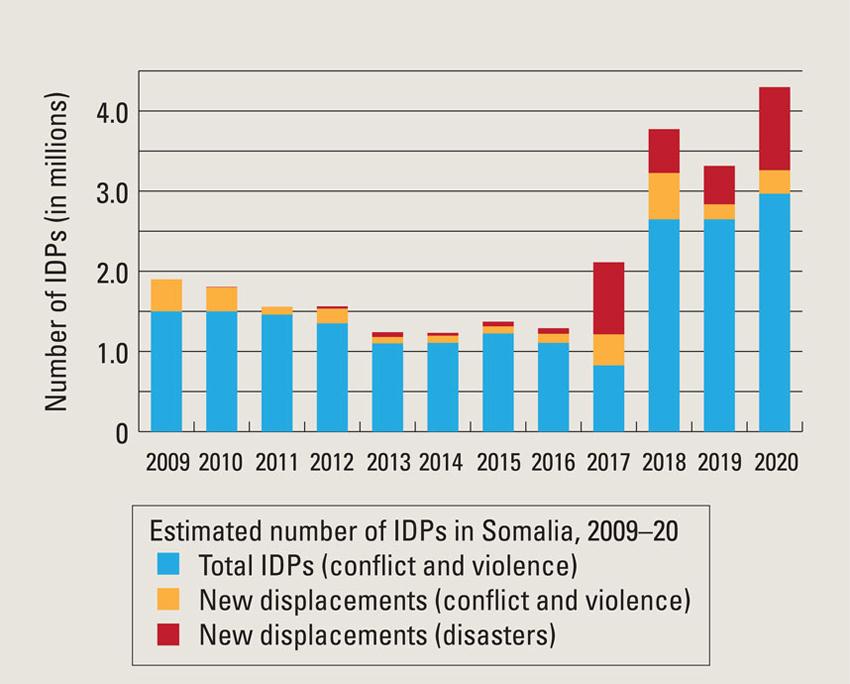

Armed violence continued to exact a high civilian toll in 2020. Around 750 civilians were estimated to have died between January 2020 and February 2021 because of armed violence, with al-Shabaab responsible for nearly half of these deaths.9 The humanitarian crisis in Somalia remained alarming, with approximately 5.9m people in need of humanitarian assistance.10 Heavy fighting in Gedo and Jubaland caused the displacement of roughly 60,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) during the first half of 2020 and by the end of the year there were an estimated 293,000 new conflict IDPs across the whole country.11 Additionally, the coronavirus pandemic, desert locusts and floods exacerbated the humanitarian situation. In particular, concerns arose that the spread of new infectious variants of the coronavirus could lead to a surge in COVID-19 cases, especially given the country’s fragile healthcare system. Flooding displaced over half a million Somalis and affected an estimated 1.3m people across 39 districts, contributing to the spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera and acute diarrhoea.12

Political stability

Disputes over the upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections dominated Somalia’s political landscape. These tensions sparked an outbreak of inter-clan clashes across Somalia and antagonised some of the government’s allies – such as the ASWJ – in the fight against al-Shabaab. Notably, al-Shabaab took advantage of these fissures to enhance its propaganda and recruitment.13 The stand-off between President Farmaajo and the opposition over the electoral law ended in September 2020 following agreement to retain the current indirect voting system for the December 2020 parliamentary elections. However, the postponing of the ballot ignited new tensions between the government and the opposition.

Economic and social

The combined effect of the pandemic, flooding and a locust infestation caused an estimated 1.5% GDP contraction in 2020, down from a forecasted growth of 3.2%.14 The recession is largely the result of an estimated 40% drop in remittances, and a concurrent fall in the export of livestock.15 In March, the IMF and the World Bank announced Somalia would be eligible to receive debt relief under the enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative, restoring the country’s access to regular financing. In June, the World Bank approved a US$55m emergency package to support Somalia’s ailing economy. The package provided critical supplemental financing to the 2020 budget, sustaining service delivery in the face of considerable revenue shortfall.

Years of conflict have had devastating social effects. Approximately 69% of the population lives in poverty, with an even higher incidence rate among IDPs.16 An estimated 30% of children aged six to 17 were enrolled in school as of 2020, with strong disparities between urban and rural areas and between boys and girls.17 Additionally, the combination of heavy flooding and below-average rainfall seasons negatively affected crop and livestock production, leaving over 2.5m people acutely food insecure.18

Relations with neighbouring and international partners and geopolitical implications

Somalia was also caught in the midst of broader regional turbulences in 2020. Rivalries among Gulf countries continued to play out in the country, with Qatar and the UAE vying for influence and Turkey remaining one of Farmaajo’s most trusted allies. The conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region also had wider implications for Somalia. The Ethiopian government redeployed an estimated 3,000 troops from Somalia to Tigray and disarmed an additional 200 Tigrayan soldiers serving in AMISOM.19 These withdrawals have sparked concerns that AMISOM-backed Somali troops will be more vulnerable to al-Shabaab.

In December, relations between Kenya and Somalia deteriorated after the Somali government accused its neighbour of meddling in its domestic affairs. Hours after Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta welcomed President Muse Bihi Abdi of Somaliland in Nairobi on 14 December, Somalia cut diplomatic ties with Kenya. The crisis represented the culmination of years of simmering tensions between the two countries, which have escalated over Kenya’s involvement in AMISOM, unresolved trade issues, maritime-border disputes and alleged breaches of Somalia’s sovereignty. Subsequently, the Somali government dismissed as ‘biased’ the results of a fact-finding mission mandated by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development to investigate the maritime-border dispute with Kenya.20

Conflict Outlook

Political scenarios

The turbulent run-up to the elections strained relations between the Somali federal government and the member states. Farmaajo’s nationalist platform antagonised influential clan leaders, including the presidents of Puntland and Jubaland. In these regions, the deployment of the SNA occasionally ignited clashes with local security forces. Inadequate measures to ensure widespread public confidence in the electoral process and its eventual outcome could provoke a violent backlash from the federal states and the opposition. The ongoing dispute with Kenya over the demarcation of the maritime boundary – with a postponed adjudication date of March 2021 at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) – is also likely to have a significant impact on Somalia’s domestic politics, not just on regional relations. A ruling favouring Somalia could lead the federal government to begin oil explorations off the coast of semi-autonomous Puntland, potentially igniting new disputes with the regional government over how to distribute oil revenues.

Escalation potential and conflict-related risks

AMISOM is set to transfer security responsibilities to the Somali government by the end of 2021. Yet tensions involving AMISOM’s TCCs represent a significant conflict-related risk. The crisis in Tigray already triggered a redeployment of Ethiopian forces in 2020 – both those under AMISOM and independent troops – from Somalia to the domestic front. If the Tigray conflict escalates or stretches out further into 2021, the Ethiopian government may be forced to withdraw additional troops from Somalia.

The potential of rising regional tensions between Kenya and Somalia – should either one of them ignore an unfavourable ICJ ruling – may also negatively affect AMISOM. Changes in the current size and composition of AMISOM may induce other TCCs, including Burundi, Djibouti and Uganda, to reconsider their participation in the mission: a threat Burundi and Uganda already made in 2019 after a proposed drawdown of military personnel. Cracks within AMISOM are likely to benefit al-Shabaab, as previous Ethiopian and Kenyan troop withdrawals saw the group increase attacks and quickly retake territory. With the SNA still ill-equipped to assume security responsibilities, AMISOM may continue to take a leading security role beyond the end of 2021.

Prospects for peace

The 2021 parliamentary and presidential elections represent an important inflection point for the country. Broad acceptance of election results could improve the relations between the federal government and the member states. However, this is contingent on the Somali political and security elites making a general commitment to the electoral process, which proved the major obstacle throughout 2020. A contested ballot could trigger a political crisis with broader regional ramifications. Political developments in early 2021, including the opposition ceasing to recognise Farmaajo and the violent repression of an opposition march in February, suggest that tension is likely to increase in the absence of a clear and mutually agreed electoral time frame.

Additionally, the prospects of a negotiated settlement with al-Shabaab remain thin. Over the years, calls to review the current strategy to fight al-Shabaab acknowledged the low probability of success by military force alone. Yet the protracted military stalemate between the federal government and al-Shabaab, along with the uneasiness among powerful regional actors over the situation, makes it unlikely that official negotiations will begin any time soon.

Strategic implications and global influences

The strategic value of the coastline along the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa leaves Somalia vulnerable to foreign meddling. Both Gulf and neighbouring African countries have taken advantage of the ambiguous status of federal states to bypass the central government’s approval of infrastructure projects. The UAE has established close relations with the federal member states, antagonising the central government. Although Farmaajo banned Dubai’s DP World from operating in Somalia and despite the rejection of a late-2019 UAE plan to build a military base in Berbera, the company successfully won 30-year concessions to develop the port of Berbera in Somaliland and the port of Bosaso in Puntland. In Puntland, the UAE were reported to have sponsored regional militias hostile to Mogadishu.21 Farmaajo has found two close allies in Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki. However, a conflict between Mogadishu and the federal states could force Abiy and Isaias – both aligned with the UAE – to abandon Farmaajo, plunging Somalia into further fragmentation. The consequences of regional turbulences and shifting alliances in the Horn are therefore likely to reverberate widely across Somalia.

Notes

- 1 Hiraal Institute, ‘A Losing Game: Countering Al-Shabab’s Financial System’, October 2020.

- 2 Security Council Report, ‘August 2019 Monthly Forecast’, 31 July 2019.

- 3 Christopher Anzalone (@IbnSiqilli), tweet, 21 July 2019.

- 4 United Nations Security Council, ‘Security Council Reauthorizes Deployment of African Union Mission in Somalia, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2520 (2020)’, S/RES/2520, 29 May 2020, p. 4.

- 5 ‘Trump Orders Withdrawal of US Troops from Somalia’, BBC News, 5 December 2020.

- 6 United Nations Security Council, ‘Report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia Submitted in Accordance with Resolution 2498 (2019), S/2020/949’, 28 October 2020, p. 8.

- 7 Airwars, ‘US Forces in Somalia’, 1 February 2021.

- 8 United Nations Security Council, ‘The Situation in Somalia. Letter from the President of the Council on the Voting Outcome (S/2020/459) and Voting Details (S/2020/466)’, 29 May 2020, p. 8.

- 9 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), www.acleddata.com.

- 10 United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Global Humanitarian Overview 2021’, 1 December 2020, p. 10.

- 11 See Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), ‘2020 Internal Displacement’, Global Internal Displacement Database.

- 12 United Nations Security Council, ‘Situation in Somalia. Report of the Secretary-General, S/2020/798’, 13 August 2020, p. 11.

- 13 United Nations Security Council, ‘Letter Dated 21 January 2021 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee Pursuant to Resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) Concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals, Groups, Undertakings and Entities Addressed to the President of the Security Council’, S/2021/68, 3 February 2021, p. 11.

- 14 International Monetary Fund, ‘World Economic Outlook: A Long and Difficult Ascent’, October 2020, p. 146.

- 15 International Organization for Migration, ‘Expected 40 Percent Drop in Remittances Threatens Somalia’s Most Vulnerable’, 15 June 2020.

- 16 World Bank Group, ‘Somali Poverty and Vulnerability Assessment’, April 2019, p. 126. Poverty in this assessment was defined as living off less than US$1.90 per day.

- 17 United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Humanitarian Needs Overview: Somalia’, January 2021, p.68.

- 18 Famine Early Warning System Network, ‘Somalia Food Security Outlook, October 2020 to May 2021’, 15 November 2020.

- 19 Colum Lynch and Robbie Gramer, ‘U.N. Fears Ethiopia Purging Ethnic Tigrayan Officers from Its Peacekeeping Missions’, Foreign Policy, 23 November 2020.

- 20 Magdalene Mukami, ‘Somalia Rejects Probe Report on Tiff with Kenya’, Anadolu Agency, 27 January 2021.

- 21 Vanda Felbab-Brown, ‘What Ethiopia’s Crisis Means for Somalia’, Brookings Institution, 20 November 2020.

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

Overview

Over a hundred different conflicts plague the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). State and non-state armed groups fight over land, minerals and identity, compounded by competing international interests. The distinction between state and non-state is blurred: the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) is one of many armed groups and it allows certain other actors to control territory and state institutions.

Foreign insurgent activity has also shaped the country’s modern history. Rwanda continues to conduct military operations against Hutu rebel groups, who have operated in eastern DRC provinces since the Rwandan genocide of 1994. Ugandan insurgencies have also made use of the DRC–Uganda borderlands to escape Kampala’s reach. Insecurity in the DRC and its high-value natural resources have long incentivised foreign-military activity in the country, either through the deployment of troops or by backing local armed groups. These ongoing dynamics have caused much bloodshed and left a legacy of suspicion of foreign intervention which still drives militarisation among communities in eastern DRC.

Violence escalated in 2020–21, with an increasing number of attacks on civilians and clashes between armed groups. Armed groups frequently attacked, abducted, burned, pillaged, murdered and committed sexual violence, leading to large displacements of people. Armed-group violence targeting civilians caused an estimated 2,702 fatalities in 2020–21 compared to 2,203 in the same period from 2019–20. The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an armed group from Uganda with obscure ties to the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL), was responsible for 49.5% of these killings. Furthermore, violence against and carried out by ethnic Banyamulenge groups continued to grow, more than doubling from 2019.1

Eastern provinces of the DRC continued to be the most unstable in 2020–21. Violence rose in Ituri, fuelled by long-standing tension between the Lendu and Hema ethnic groups over political power, land and identity.2 These tensions were complicated by ethnic recruitment by larger armed groups, such as Lendu recruitment by the Cooperative for the Development of the Congo (CODECO). The Nduma Defence of Renovated Congo (NDC–R), an armed group historically linked to mining areas, expanded its operations further into North Kivu, seizing control of territory previously held by other armed groups. Importantly, CODECO and NDC–R both experienced internal splintering following the death of CODECO leader Justin Ngudjolo and NDC–R leadership divisions.

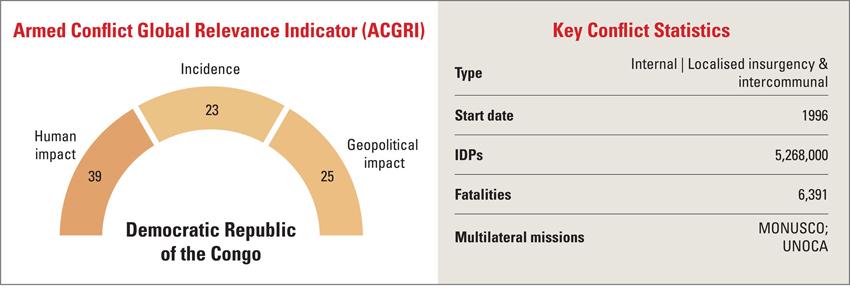

ACGRI pillars: IISS calculation based on multiple sources for 2020 and January/February 2021 (scale 0–100). See Notes on Methodology and Data Appendix for further details on Key Conflict Statistics.

In 2020–21, foreign-military operations, regional trade relations and cross-border travel were complicated by the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, with domestic-policy responses including border closures, travel restrictions and limitations on gatherings.

Conflict Parties

The Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (FARDC)

Strength: 134,250.

Areas of operation: Across the country in 11 military regions, but mainly focused on North and South Kivu and with increased activity in Ituri in 2020.

Leadership: Lieutenant-General Célestin Mbala Munsense (chief of the general staff).

Structure: The FARDC is very large but poorly structured, with perhaps as many as 65% of its troops being officers, 26% of whom are high-ranking.3 This is partly the result of a regular practice of awarding officer positions to defecting rebels.

History: The FARDC was created by the 2003 Sun City Agreement, which stipulated that all parties to the conflict contributed troops to the national army, an integration process known as brassage. Despite international efforts at security-sector reform, the FARDC remains a mix of feuding militias.

Objectives: While formally the FARDC fulfils national-security objectives, many officers and soldiers pursue their own agendas, seeking wealth particularly through illicit trade and mining, or enacting the violent demands of political patrons.

Opponents: The majority of armed groups in the DRC (except those with which the FARDC has an alliance of convenience).

Affiliates/allies: Frequently uses armed groups to do its fighting and sometimes allies with them for political and economic opportunities.

Resources/capabilities: Suffers from chronic resource shortages (including for salaries) amid widespread corruption, resulting in weak and ineffective operations. It is predominantly armed with small arms and light weapons, but also has artillery, 430 armoured fighting vehicles, anti-aircraft guns and surface-to-air missiles.

Cooperation for the Development of Congo (CODECO)

Strength: Most reports estimate 2,350 people, but these draw on self-reporting from within the group.4

Areas of operation: Djugu, Mahagi and Irumu territories in Ituri province.

Leadership: The assassination of Ngudjolo in March 2020 resulted in the splintering of CODECO into competing factions. Recent groups to emerge include Union of Revolutionaries for the Defence of the Congolese People (URPDC), led by Charité Nguna Kiza; CODECO Alliance for the Liberation of the Congo, under the leadership of Justin Maki Gesi; and CODECO Sambaza, whose leadership is uncertain.

Structure: Some factions and splinter groups accepted the 2020 disarmament process while others continued fighting.

History: CODECO formed in the 1970s, originally as a farming collective of primarily ethnic Lendu groups, which developed both spiritual and militant dimensions over time. It has since engaged in numerous bouts of violence against the Hema.

Objectives: While CODECO’s objectives appear to be ethnic violence against the Hema population, ethnicity is not the main driver, and conflict is tied to political circumstances. Some factions have expressed willingness to enter a peace process, with better food provision for their areas one of the conditions for their participation.

Opponents: Individual and self-defence Hema groups, FARDC.

Affiliates/allies: CODECO is believed to have links with the Iturian groups Nationalist and Integrationist Front (FNI) and Ituri Patriotic Resistance Force (FPRI).

Resources/capabilities: Much of CODECO fighting is done with bladed weapons or small arms and light weapons.

Allied Democratic Forces (ADF)

Strength: Likely around 700–1,000, although not all its personnel are combatants.5

Areas of operation: Beni territory (particularly Beni town), Eringeti, Mbau and increasingly Kamango, close to the border with Uganda.

Leadership: Seka Musa Baluku (emir of the ADF and its most senior leader).

Structure: Divided between several main camps, each of which houses between 150–200 fighters.6 Each camp has recognised military leaders and ranks, although it is unclear if the ranks follow a conventional military structure.

History: Created in 1995 from a merger between Ugandan Tabliqh Islamists and the remnants of a Ugandan secessionist movement in the DRC–Uganda border area. Over time the group has increasingly adopted jihadist rhetoric and ideology. It has referred to itself as Madina al-Tauheed wa Mujahedeen, and in April 2019 official ISIS media began claiming some of its attacks.

Objectives: The ADF regularly attacks and kills civilians in the Beni area, but expresses no clearly articulated political plans other than vague Salafi-jihadist statements. While ISIS has claimed credit for its attacks, it has not expressed specific plans in relation to the DRC.

Opponents: FARDC and United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO).

Affiliates/allies: The ADF has been known to form temporary alliances or bargains with local armed actors, including elements of the FARDC and Mai-Mai groups.

Resources/capabilities: The ADF is well integrated into the borderland landscape and can draw on several sources to sustain itself, including agriculture and illicit trade. While it is armed largely with light weapons, ISIS media has regularly claimed that the group steals weapons from the FARDC.

Resistance for the Rule of Law in Burundi (RED Tabara)

Strength: Unclear, but RED Tabara claimed in 2017 to have 2,000 recruits.7

Areas of operation: Uvira territory and the Ruzizi plain.

Leadership: ‘General’ Birembu Melkiade, also called Melchiade Biremba, is the recognised leader of RED Tabara, but is currently believed to be in the custody of the DRC government. ‘Colonel’ Raymond Lukondo is Melkiade’s deputy and the interim military leader.

Structure: Unclear, but presence of designated ranks suggests the group is mimicking a conventional military structure.

History: RED Tabara is believed to be the military wing of the Movement for Solidarity and Democracy (MSD) party led by Alexis Sinduhije, which was formed in opposition to the extension of term limits by Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza in 2015.

Objectives: Overthrow the Nkurunziza regime in neighbouring Burundi.

Opponents: The Burundian National Defence Forces (FDN) and Imbonerakure, a militant youth wing of the ruling political party in Burundi, have made several incursions into DRC territory, resulting in several clashes with RED Tabara.

Affiliates/allies: Other Burundian opposition groups, including the National Forces of Liberation (FNL) and the National Council for Renewal and Democracy (CNRD).

Resources/capabilities: The group is believed to receive some funding from the Burundian diaspora, as well as some support from Burundi.

Raia Mutomboki

Strength: As a decentralised franchise rather than a single armed group, it is not possible to give clear numbers, though there are likely several thousand Raia Mutomboki affiliates across several dozen groups. However, many of these individuals only take up arms at specific times.

Areas of operation: Raia Mutomboki have been historically based in South Kivu and are still most active in the Kabare, Kalehe, Mwenga, Shabunda and Walungu territories, as well as in Kahuzi-Biega National Park.

Leadership: Raia Mutomboki groups have proliferated since the original group formed in 2005, each with different leadership structures. After dozens of fighters surrendered in March 2020, FARDC arrested one of the major leaders, Juriste Kikuni, in October 2020.

Structure: Groups are largely informally structured given their ideological foundation as citizens’ movements. Efforts by some individuals to structure and lead them are usually transient.

History: Formed in 2005 to combat violence committed by the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) but also as a form of protest against state violence and neglect. The name Raia Mutomboki means ‘angry citizens’, and the groups largely continue to style themselves as grassroots defenders.

Objectives: The political demands vary from group to group. Broadly, they aim to fight the FDLR, counter state violence and advocate for better access to public services for residents in their area. They also function as local defence militias.

Opponents: FDLR, FARDC.

Affiliates/allies: Alliances tend to be localised and short-term, but they often fight alongside Mai-Mai groups and other Raia Mutomboki factions.

Resources/capabilities: Raia Mutomboki largely draw on the same revenue sources as ordinary people, including agriculture and artisanal mining. Their weapons are limited to small arms and bladed weapons.

Mai-Mai (Mayi-Mayi) groups

Strength: There are over 50 known Mai-Mai groups in North and South Kivu. Some groups have formed large coalitions of several hundred fighters (such as the Mai-Mai Mazembe or Yakutumba), but most groups tend to comprise fewer than 200 fighters.

Areas of operation: Present in most of North and South Kivu.

Leadership: Each group has its own leadership arrangements, with some groups more centralised around a single leader, while others are less defined.

Structure: Largely informal and non-hierarchical.

History: Mai-Mai groups mostly formed as self-defence militias. A majority have anti-Tutsi or anti-Rwandan sentiments and see themselves as indigenous defenders against Rwandan foreigners.

Objectives: While the groups are styled as communityprotection groups, usually around a particular ethnicity and locality, they often collaborate with each other, or with larger armed actors for both defensive and opportunistic reasons.

Opponents: Typically, groups considered to be ‘non-local’, such as people viewed as Rwandan or Banyamulenge. However, localised territorial struggles are also common.

Affiliates/allies: Alliances of convenience are periodically formed, including between Mai-Mai groups.

Resources/capabilities: Mai-Mai weapons are usually limited to small arms or machetes and other bladed weapons. Some groups take part in artisanal mining and periodically exercise control over mining sites.

The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)

Strength: While the FDLR was believed to number 6,500 combatants in 2008, many fighters demobilised in 2018. In 2020, estimates range from 500 to 1,000 fighters.8

Areas of operation: Operates primarily in Bwito with limited operations in surrounding areas in North Kivu and into South Kivu.

Leadership: In 2019 the FDLR’s most senior leaders passed away, with Ignace Murwanashyaka dying from natural causes and the FDLR’s military commander Sylvestre Mudacumura killed by the FARDC. Two leaders, called Omega and Gaby Ruhinda, took over leadership of the group.

Structure: The FDLR mimics a conventional military structure, with specialised units for particular missions. However, the reduction in numbers and loss of long-standing leaders may prompt a gradual informalisation of the group.

History: Former officers from the army of Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana fled to the DRC (then known as Zaire) after the 1994 genocide and remobilised in refugee camps. The group changed its name to the FDLR in 1999. Individuals involved in the genocide are still believed to be with the movement. Operations in Rutshuru and other areas frequently result in clashes with state and non-state armed groups, the abduction of civilians to raise money and attacks against the local population.

Objectives: Ideologically divided between those desiring the repatriation of Rwandan refugees displaced during the genocide and others aiming to overthrow the government of President Paul Kagame in Rwanda.

Opponents: The government of Rwanda, the Nduma Defence of Renovated Congo (NDC–R), local Mai-Mai groups.

Affiliates/allies: Mai-Mai Nyatura, Collective of Movements for Change (CMC).

Resources/capabilities: Funding comes from the trade of local goods, agriculture and looting. The group also trades cannabis and charcoal, and oversees the exploitation of gold and tin mines. Moreover, it receives funding from the Rwandan diaspora.

Patriotic Union for the Liberation of Congo (UPLC)

Strength: Around 400 to 500 fighters.9

Areas of operation: Beni territory (South Kivu province) with a primary base in Kalunguta.

Leadership: The current commander is Kambale Mayani, after Kakule Liso was removed from leadership and killed by local vigilantes in January 2021.

Structure: Formed from Mai-Mai Kilalo. Leadership comprised of former military and non-state armed groups.

History: Created in 2016 from Mai-Mai Kilalo, founded by Katembo Kilalo and Mambari Bini Pélé. The group has carried out operations against MONUSCO, ADF and FARDC in the Beni area, often partnering with other Mai-Mai groups.

Objectives: Stated goal is to defend ethnic Kobo, Nande and Piri from ADF and FDLR attacks and end the FDLR operations in Lubero territory.

Opponents: ADF (though some reports suggest ADF and UPLC have also partnered to fight against FARDC), FARDC, FDLR, MONUSCO.

Affiliates/allies: Various Mai-Mai groups, including precarious relations with Mazembe, Nguru, Kabidon, Ngolenge; may occasionally collaborate with FARDC.

Resources/capabilities: Controls some mining sites and collects fees from miners operating around its area of control near Beni town. Draws on forced community labour and a vast network of Mai-Mai affiliated groups and uses abducted children for forced labour and military operations.

The Nduma Defence of Renovated Congo (NDC–R)

Strength: While consisting of a couple of hundred fighters when it split from its parent Mai-Mai Sheka group in 2014, it has grown with the absorption of small groups and the conquest of new territory and mining sites. Estimates from fighters in 2020 suggest a total strength of 5,000.10

Areas of operation: Lubero, Masisi, Rutshuru and Walikale territories in North Kivu.

Leadership: The NDC–R split in July 2020, with one faction led by Guidon Shimiray Mwissa, former deputy commander of Mai-Mai Sheka, and the other faction led by Gilbert Bwira and Mapenzi Likuhe.

Structure: Unclear following the split. Previously the NDC–R had a hierarchical, military-style structure with contingents distributed in numerous bases and officers in charge of different political, economic and social relations.

History: The NDC–R splintered from the Mai-Mai Sheka group in 2014.

Objectives: The NDC–R claims to be a necessary counter to FDLR activity in the area and has contributed to pushing both the FDLR and its splinter group, the CNRD, out of the areas of Masisi, Rutshuru and Walikale. However, the NDC–R has also fought for control of mining sites in the area, particularly gold.

Opponents: The FDLR and the Mai-Mai Nyatura and Mazembe factions.

Allies/affiliates: The FARDC and numerous temporary alliances with local Mai-Mai factions.

Resources/capabilities: Draws income from its control over gold, tin and tungsten mines. Also has an extensive tax and forced-labour system in the areas that it controls. It is known to have procured light weapons from the FARDC and other armed groups.

United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Congo (MONUSCO)

Strength: 16,215 troops from 46 countries. (Additionally, there are 1,605 police and 2,970 civilian staff.)11 While most MONUSCO troops do not have an offensive mandate and are tasked with the protection of civilians, the mission also has a Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) that is allowed to act against armed actors.

Areas of operation: The mission headquarters and the political unit are based in Kinshasa. MONUSCO’s military component is predominantly concentrated in North and South Kivu, though it has a presence in Kasai and increased its presence in Ituri province in 2020.

Leadership: Lieutenant-General Ricardo Augusto Ferreira Costa Neves is MONUSCO’s Force Commander, while Leila Zerrougui is the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General.

Structure: The contingents are spread out over a number of (sometimes temporary) bases and operate in clusters of forces, with units from several contingents per base.

History: MONUSCO replaced the United Nations Organisation Mission in the Congo (MONUC) in July 2010 with an enhanced peacekeeping mandate that allowed the protection of civilians. The FIB was mandated in 2013 with strengthening peacekeeping operations.

Objectives: Stabilise the situation in the DRC and improve governance.

Opponents: Non-state armed groups in its areas of operation.

Affiliates/allies: Periodically conducts joint operations with the FARDC, but relations are often tense.

Resources/capabilities: Relatively well equipped and has air assets (including four combat jets and seven helicopter gunships), as well as armoured personnel carriers and artillery. However, intermittent donor funding complicates its ability to resource its operations effectively.

Other conflict parties

In addition to the conflict parties above, foreignstate armed forces affected the conflict dynamics in the DRC in 2020–21 by conducting strategic military operations through its porous borders. Some foreign militaries fought alongside the FARDC, such as the military forces of Rwanda, which conducted operations against non-state armed groups that opposed the Rwandan government like the FDLR. Other militaries operated against the FARDC, such as those from Angola, South Sudan and Zambia. Additionally, other military forces from Burundi operated in the DRC with the ruling party of Burundi’s youth militia, the Imbonerakure, to eliminate Burundian opposition groups, such as RED Tabara. Lastly, Ugandan military forces operated in the DRC to protect fishing interests in North Kivu.

Conflict Drivers

Political

Ethnicity and land:

The legacy of the DRC’s colonial past is a lasting driver of conflict. Under the Congo Free State (1885–1908), the administration and division of territory solidified loose ethnic groupings. This approach consisted of administering particular groups via their own customs and ‘traditional leaders’, but the system left some ethnicities effectively stateless and created a legacy of land conflict. Groups viewed as ‘indigenous’ gained priority, while non-indigenous groups saw their citizenship and landholdings questioned. Some ethnic groups, such as the Banyamulenge, are viewed as non-indigenous because their ancestors had migrated from outside the DRC.12

Colonial ethnic divisions intensify current conflicts between groups over land, water and other natural resources. Land conflicts arise and are exacerbated by multiple and conflicting legal systems, a decrease in readily available resources and poor public services. Unable to rely on state forces for protection, rival communities arm themselves to ensure their security and their control of local resources critical for their survival. Long-standing rivalries also initiate conflicts between pastoralists and arable farmers, such as those between Lendu and Hema groups in Ituri.

Deep-rooted institutional weaknesses:

Violence has continued long after the peace process that followed the end of the Second Congo War in 2003, in large part because of the utility of armed groups in helping achieve the political ends of local and national political elites and the FARDC. This has undermined the public credibility of the FARDC, lowering its reputation to just another armed actor that frequently engages in human-rights abuses. At the national level, violence has served to divide communities and prevent them from forming coherent opposition fronts. More broadly, local people (particularly in North and South Kivu) feel both forced and incentivised to form their own militias.13

Security

Failed demobilisations:

More than 150,000 combatants have undergone disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) since 2003, with limited success in ending violence.14 While DDR is necessary in conflict resolution, demobilisation incentives provided to combatants have inspired new recruits, who may misinterpret them as meaning that violence ultimately leads to rewards. Likewise, poorly managed reintegration processes have failed to prevent former combatants from returning to arms. Both of these measures have served to perpetuate armed conflict in the DRC. Chronic shortages of resources caused by embezzlement and corruption have also plagued the DDR process.

International

Foreign intervention and mineral interests:

The interests of foreign-state and non-state actors intersect on eliminating opposition groups, exploiting mineral rights and supporting specific ethnic groups. Some foreign-military operations in the DRC, such as those of Angola, Burundi and Rwanda, have been conducted alongside the FARDC with the government’s official or unofficial approval. These relations are often fragile, with multiple and conflicting motivations. Foreign governments often attempt to end non-state-armed-group operations on DRC soil, like RED Tabara or the FDLR, but simultaneously conduct their own activities that extract mineral wealth in the eastern part of the country.

Other foreign-state and non-state groups operate without official approval from Kinshasa, controlling mines and resource flows for their own benefit.

Political and Military Developments

Shifting the balance of power

Slow and growing pressure throughout 2020 led to a shift in political power dynamics with the dissolution on 6 December of the power-sharing parliamentary agreement between the Common Front for Congo (FCC), aligned with former president Joseph Kabila, and Heading for Change (CACH), a coalition which includes the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS) party of the current president, Félix Tshisekedi. Protests by UDPS party supporters against the dismissal of the national parliament’s vice-president and the end of the FCC–CACH ruling coalition spread to many cities.

The end of the FCC–CACH coalition was the culmination of a series of strategic decisions by Tshisekedi to remove his predecessor’s influence, including instating Albert Yuma Mulimbi as the head of the state-owned copper and cobalt enterprise Gecamines, replacing seven senior magistrates allied to Kabila and suspending Delphin Kahimbi, the military-intelligence chief.15 Tshisekedi also made controversial appointments to the Constitutional Court, installing judges viewed as sympathetic to him and reducing the influence of those allied to Kabila.

Regional tensions and cooperation

The presence and operations of foreign militaries in the DRC continued to increase in 2020–21, destabilising local populations and resulting in numerous casualties. For example, South Sudanese military forces attacked civilians and looted properties in Ituri, subsequently clashing with the FARDC. Zambian military forces also crossed into Tanganyika province on 13 March and clashed with the FARDC. Other operations were more complex, such as those with Burundian and Rwandan military forces, which partnered with the FARDC to eradicate non-state armed groups operating in eastern DRC amid tense relations between Kigali, Gitega and Kinshasa.16

Expanded ADF operations

While the ADF continued to focus operations within North Kivu, by the end of 2020 it had also become the second-most active and deadly non-state armed group in Ituri, second only to CODECO. ADF activities in Ituri took place in the southern part of the province in Mambasa and Irumu. By May 2020, around 4,000 ADF fighters had set up multiple bases in the chiefdom of Walese Vonkutu, partnering with Mai-Mai Kyandenga and Mai-Mai Simba. This shift in operations resulted from increased FARDC pressure on the ADF in North Kivu and the capture of numerous ADF bases in Beni throughout 2020.

Violence in Ituri

Violence escalated in Ituri in the first half of 2020. Since 2017, CODECO has increasingly mobilised Lendu groups with an ethnic rhetoric against the Hema.17 Equally, Hema groups have armed themselves and retaliated against Lendu communities. The FARDC’s retreat in early February 2020 from several positions around Djugu also allowed Lendu armed groups to take control of dozens of villages in the region. Violent events against civilians in Ituri nearly doubled from the previous year, with events increasing by 84.3% and fatalities increasing by 42.7%.18 After various peace agreements with CODECO in August 2020, violence began to decrease but has far from ceased completely.

DDR failures

Several armed grouped entered DDR programmes in 2020, with varied success. In February 2020, for example, the Front for Patriotic Resistance (FRPI) agreed to a ceasefire and reintegration, but some of its fighters continued to commit acts of violence. Deserters of the DDR process often cited insufficient resources and ineffective implementation. More troubling was the trend towards the surrendering and splitting of larger groups, like CODECO, leaving local power vacuums that were filled by defecting factions and other armed groups.

Key Events in 2020–21

POLITICAL EVENTS

7 February 2020

Tshisekedi replaces seven senior magistrates, including allies of former president Kabila.

28 February

The FRPI and the government sign a peace deal, with the latter agreeing to integration into the FARDC.

24 March

A state of emergency and border closures are announced due to the coronavirus pandemic.

8 April

Authorities arrest Vital Kamerhe, Tshisekedi’s former chief of staff, on embezzlement charges, prompting both demonstrations and counter-demonstrations.

4 May

CODECO leadership calls for the FARDC to negotiate a ceasefire in order to allow peace talks.

15 June

The ADF establishes three new bases near Eringeti, despite FARDC operations in the region.

24–25 June

The UDPS holds widespread demonstrations against a series of judicial changes proposed by the FCC.

8 October

Tshisekedi announces a temporary suspension of Minembwe commune and the creation of a commission to investigate.

14 November

Thousands of Tshisekedi supporters gather in Kinshasa to demand the end of the coalition with the FCC.

6 December

Tshisekedi announces the end of the ruling coalition with former president Kabila’s FCC party, vowing to seek a new majority in parliament.

15 February 2021

Tshisekedi appoints Jean-Michel Sama Lukonde Kyenge as the new prime minister.

MILITARY/VIOLENT EVENTS

9 January 2020

The FARDC engages in operations against the ADF, taking back Madina in Beni.

2 February

The ADF shifts operations from North Kivu to Ituri, with numerous attacks on civilians.

25 March

Ngudjolo is killed during a military operation in Walendu Pitsi, Ituri.

24 April

Police arrest Bundu dia Kongo leader Ne Muanda Nsemi, resulting in clashes with supporters.

26 April

The Burundian military, the FDLR and the Mai-Mai clash with RED-Tabara in South Kivu.

25 May

FARDC overthrows a strategic CODECO stronghold in the Djugu territory of Ituri.

8 July

The NDC–R announces disarmament plans and demotes Guidon Shimiray from his role as commander, leading to a split and fighting between factions.

16 July

The Banyamulenge clash with the Mai-Mai in Kipupu, resulting in sexual violence, multiple fatalities and mass displacement.

4 August

US Africa Command resumes strategic military cooperation with the FARDC.

8–10 September

58 Hutu civilians are killed in attacks in Irumu territory, attributed to the ADF.

20 October

The ADF attacks Kangbayi prison and a nearby military base in Beni, freeing 1,300 prisoners.

16–17 November

ADF militants kill 14 civilians during raids in villages throughout Beni.

22 February 2021

The Italian ambassador to the DRC, Luca Attanasio, and the World Food Programme security escort, Vittorio Lacovacci, are killed during an abduction attempt in North Kivu.

Impact

Human rights and humanitarian

Human-rights violations in eastern DRC continued in 2020, with both state and non-state armed groups committing violent attacks against civilians. Violence by armed groups targeting women increased in 2020, with the majority of these attacks occurring in North Kivu. Use of excessive force against protesters by police and the military had fallen since Tshisekedi took office in 2019, but many demonstrations continued to be banned or dispersed, with journalists targeted in particular. Coronavirus containment measures were used by police to bar demonstrations. Human-rights advocates, lawyers and political-party members continued to face threats, violence and imprisonment for voicing critical views towards those in power.19

Violence in the DRC has led to 5.2 million internally displaced persons and just under 950,000 refugees and asylum seekers, primarily in Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda.20 New refugees also arrived into the DRC from destabilised environments in Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR) and South Sudan.21 The DRC now hosts over half a million refugees from neighbouring countries.22 Humanitarian responses struggled amid the coronavirus pandemic, funding shortages and violence against aid workers in Ituri, North Kivu and South Kivu. This increased the number of people in the DRC experiencing acute food shortages to 21.8m, exacerbating malnutrition rates among children and making the DRC home to the second-largest hunger crisis globally after Yemen.23

Economic and social

The DRC faced severe health concerns surrounding an Ebola outbreak during 2020. Although the government officially declared the end of the Ebola outbreak on 18 November 2020, its actual endpoint is uncertain.24 Limited testing in much of the country made the exact spread and impact of the pandemic since March 2020 difficult to ascertain. Outside of Kinshasa, the conflict-affected eastern provinces were the most severely affected.25 By the end of February 2021, 25,913 cases had been confirmed and 707 deaths recorded, although actual figures may have been much higher.26 Coronavirus lockdown measures impacted school children across the country, who lacked the technology to continue their studies virtually. Workers in sectors such as mining faced harsh conditions of confined work environments. Conflict-induced displacement and the pandemic also compounded poverty. Many civilians, especially displaced people with already limited resources, faced indiscriminate looting, destruction of property and deterioration of local public services.

The coronavirus pandemic and subsequent lockdown measures did not affect all economic sectors equally. Compared to the previous year, mineral and rare-earth exports, especially copper and cobalt, increased in production in 2020, due to continued demand and mining companies’ practice of confining workers to job sites.27 Increased production helped alleviate drops in mineral prices.28 Contactintensive jobs were more severely hit, particularly those in the informal market, such as small traders, taxi drivers and vendors. The IMF estimated that the economy of the DRC contracted by 0.06% in 2020.29

Relations with neighbouring and international partners and geopolitical implications

Relationships with some international partners markedly improved in 2020, with Tshisekedi gaining the trust of the United States and the reinstatement of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which allows sub-Saharan African nations duty-free access to the US market. The DRC government also secured loans from the IMF and the World Bank to handle the coronavirus pandemic and mitigate its economic fallout.30 Insecurity and violence in the borderlands continued to drive preexisting regional tensions that stemmed from both the DRC government and neighbouring countries. Groups such as the Alliance of Patriots for a Free and Sovereign Congo (APCLS), FDLR and RED Tabara continued to operate freely and threatened crossborder attacks into Rwanda and Burundi from their bases in the DRC. Foreign militaries from Angola, Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia carried out ongoing operations in the DRC, sometimes clashing with the FARDC and keeping diplomatic relations tense throughout the year.

Conflict Outlook

Political scenarios

The ability or inability of Tshisekedi to win political allies and navigate dissent from FCC supporters will shape short-term politics in the DRC. Shortly after the FCC–CACH coalition ended, a Constitutional Court ruling removed a floor-crossing ban in parliament, which allowed some opposition MPs to support Tshisekedi.31 The president could also decide to dissolve parliament and hold elections.32 Kabila and the FCC still have deep ties within the country through FCC-appointed governors and could leverage these for political gain. The unfolding of these political dynamics will influence the government’s ability to drive development projects forward, deal with the spread of COVID-19 and influence which conflicts to focus on. The leadership of Tshisekedi, together with economic opportunities gained through the AGOA and loans from international institutions, may prove to be the necessary measures for recovery.

Escalation potential and conflict-related risks

The break-up of the FCC–CACH coalition may divide the interests of and the support for opposing armed groups. The FARDC has previously partnered with groups like the NDC–R to govern areas in eastern DRC, but FCC support for opposing rebel groups could lead to further violence. The NDC–R split will likely lead to fighting between these groups as they try to control local institutions and resources. The growing conflict in Ituri displaced tens of thousands of people in 2020 and may escalate further in 2021. Instability and violence may lead to further displacement of DRC citizens to fragile neighbouring countries. These hostilities challenge efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 and stimulate economic recovery. While the mining industry has been resilient to the global recession, conflict and contestation over the control of mining sites continue to suppress the benefits this industry could bring to the DRC.

Prospects for peace

A majority government for Tshisekedi removes political stalemates and allows for better security-policy implementation across the country, provided they are not disrupted by Kabila and other FCC-backed actors. Agreements with CODECO reduced its violent acts in Ituri by the end of 2020, but this opened up local power vacuums that could be filled by other groups and caused infighting among defectors. The break-up of the NDC–R also created local power shifts, where previously the FARDC had often partnered with the NDC–R and permitted the group a level of integration into state institutions. The break-up of the NDC–R could allow the FARDC to control more territory, especially with more effective policy implementation by Tshisekedi. Long-term solutions are likely only if there is further funding and changes to the DDR process, given the high desertion rates due to the lack of supplies, food and opportunities. The fracturing of armed groups also complicates the DDR processes. Instead of negotiating peace deals with a few major actors, there are now multiple groups with differing agendas. A peace deal with one group offers another group opportunities to control territory and populations. As in previous years, the solution to the DRC’s conflicts continues to lie primarily in sustaining ongoing peace agreements rather than constructing new ones.

Strategic implications and global influences

Fragile relations between Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda and the ongoing support provided by these states to competing armed groups in eastern DRC make an immediate solution to the violence in the area unlikely.

Rwandan President Kagame warned of potential further military action against external threats, and Burundi will likely retaliate against RED Tabara for its incursions into Burundi during the second half of 2020.33

The porous borders used by actors in the Great Lakes region are a point of growing concern, given the highly destabilised situations of the CAR and South Sudan. This poses the additional threat of attacks on civilians by state and non-state armed groups from these countries. MONUSCO continued a drawdown of troops from the DRC, but its mandate was renewed for another year. The ongoing military operations between the FARDC and MONUSCO, along with Tshisekedi’s improved relations with international actors, may provide further leverage and financing to handle instability in eastern DRC while managing the country’s response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Notes

- 1 All fatality and event data taken from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), www.acleddata.com.

- 2 International Crisis Group, ‘DR Congo: Ending the Cycle of Violence in Ituri’, 15 July 2020; and Kivu Security Tracker, ‘La Cartographie des Groupes Armés dans l’Est du Congo’ [The Cartography of Armed Groups in Eastern Congo], February 2021.

- 3 James Barnett, ‘DR Congo in Crisis: Can Kabila Trust His Own Army?’, African Arguments, 20 September 2016.

- 4 For example, see ‘DRC: A New Conflict in Ituri Involving the Cooperative for Development of the Congo (CODECO)’, Geneva Academy, 2021; and International Crisis Group, ‘DR Congo: Ending the Cycle of Violence in Ituri’.

- 5 Estimate based on collective estimates of ADF personnel from camps listed on pp. 7–8 of the UNSC 2019 report and accounting for growth since 2019. See United Nations Security Council, ‘Final Report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo’, 7 June 2019, pp. 7–9.

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 Elsa Buchanan, ‘“We Are Ready for War” – Burundi’s Rebel Groups and How They Plan to Topple President Nkurunziza’, International Business Times, 2 March 2017.

- 8 Kivu Security Tracker, ‘Armed Groups’, 7 May 2021.

- 9 Asylum Research Centre, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): The Situation in North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri’, 2019, pp. 46–7.

- 10 United Nations Security Council, ‘Final Report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo’, p. 7.

- 11 United Nations Peacekeeping, ‘MONUSCO Fact Sheet’, March 2021.

- 12 Kivu Security Tracker, ‘Atrocities, Populations Under Siege and Regional Tensions: What Is Happening in Minembwe?’, 29 October 2019.

- 13 See Kasper Hoffmann and Judith Verweijen, ‘Rebel Rule: A Governmentality Perspective’, African Affairs, vol. 118, no. 471, April 2019.

- 14 United Nations Peacekeeping, ‘MONUSCO–Activities–DDR–RR’.

- 15 Stephanie Wolters, ‘DRC: What Now That President Tshisekedi Has Taken Control?’, African Arguments, 15 December 2020.

- 16 International Crisis Group, ‘Éviter Les Guerres par Procuration dans l’Est de la RDC et les Grands Lacs’ [Avoiding Proxy Wars in Eastern DRC and the Great Lakes], 23 January 2020.

- 17 International Crisis Group, ‘DR Congo: Ending the Cycle of Violence in Ituri’.

- 18 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), www.acleddata.com.

- 19 Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: Authorities Foundering on Rights’, 22 July 2020.

- 20 See Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), ‘2020 Internal Displacement’, Global Internal Displacement Database. See also Human Rights Watch, ‘Democratic Republic of Congo Events of 2020’, February 2021.

- 21 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, ‘DR Congo Emergency’, 14 February 2021.

- 22 United Nations Refugees, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo Refugee Crisis Explained’, 14 February 2021.

- 23 World Food Programme, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo Emergency’.

- 24 World Health Organization, ‘Ebola Virus Disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo’, 18 November 2020.

- 25 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, ‘Réponse du HCR au COVID-19 en RDC’ [HCR Response to COVID-19 in DRC], 9 November 2020.

- 26 Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University, ‘COVID-19 Data Repository’, 28 February 2021.

- 27 Jean Pierre Okenda, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Updated Assessment of the Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the Extractive Sector and Resource Governance’, Natural Resource Governance Institute, 2 December 2020.

- 28 Michael Kavanagh, ‘IMF Considers $365 Million Loan to Congo Battling Multiple Epidemics’, Bloomberg, 15 April 2020.

- 29 International Monetary Fund, ‘World Economic Outlook Database’, April 2021.

- 30 ‘The World Bank Group Provides $47 Million to Support the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic’, World Bank, 2 April 2020; and ‘IMF Approves US$363.27 Million Disbursement to the Democratic Republic of Congo to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic’, IMF, 22 April 2020.

- 31 David Zounmenou, ‘The Jury’s Out on DRC’s “Sacred Union”’, Institute for Security Studies, 2 February 2021.

- 32 ‘Félix Tshisekedi Moves to Take Charge’, Institute for Security Studies, 14 December 2020.

- 33 International Crisis Group, ‘Éviter Les Guerres Par Procuration Dans L’est De La RDC Et Les Grands Lacs’ [Avoiding Proxy Wars in Eastern DRC and the Great Lakes].

Overview

The insurgency in northern Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province originated in a schism between young hardline Salafist Islamists and the more traditional Sufi Islamic clergy which dates back to about 2007. Long-standing grievances fuelled the conflict, particularly around widespread corruption, rising criminality, lack of economic opportunities and domination by a small elite affiliated with the ruling party, Mozambique Liberation Front (commonly known as Frelimo).1 The global-jihadi discourse and influx of extremists from other East African countries had also promoted radicalisation in Cabo Delgado, eventually leading to the formation of the non-state armed group (NSAG) Ahlu al-Sunnah wal-Jamaah (ASJ), locally known as ‘al-Shabaab’ and affiliated to the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL).