Source: IISS

Overview

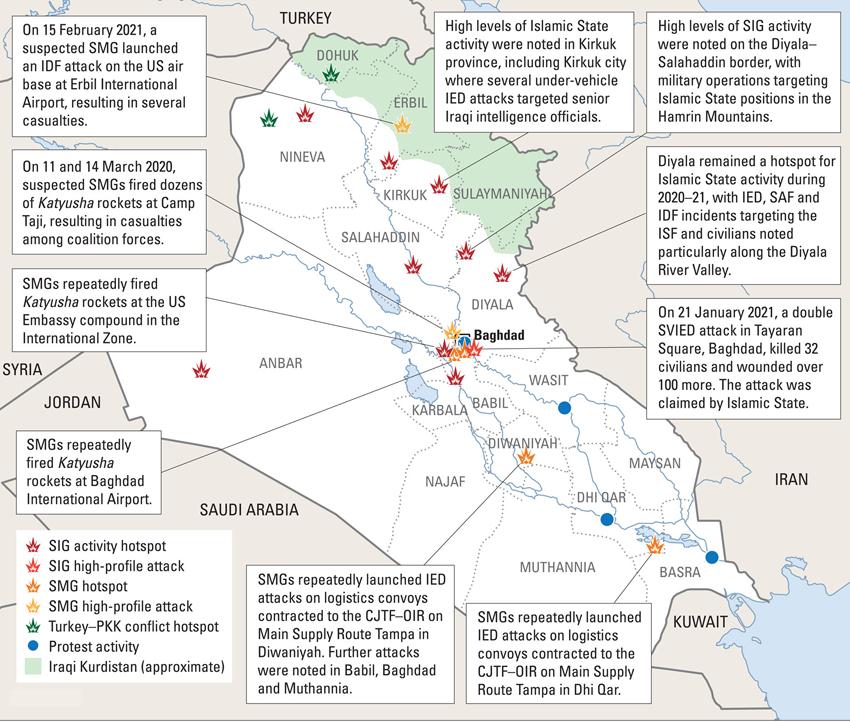

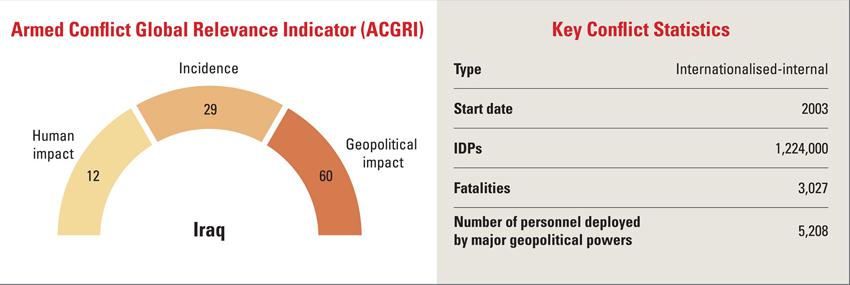

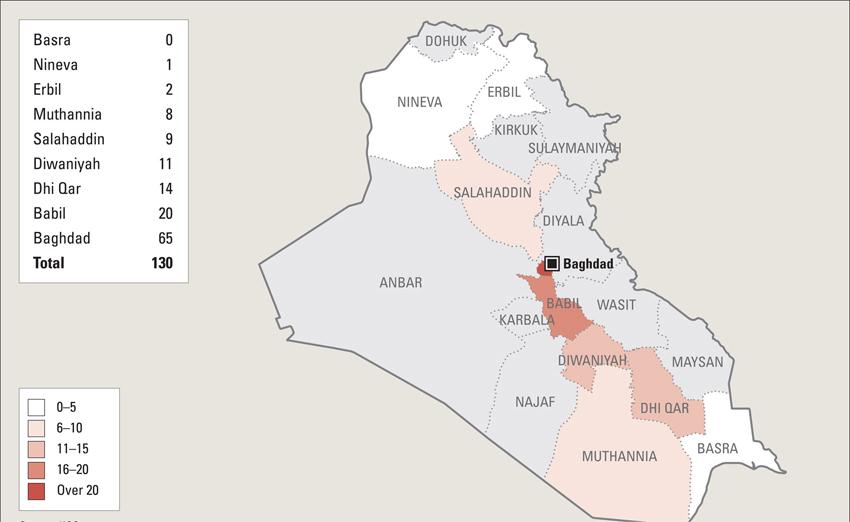

The main conflict in Iraq remains the ongoing struggle against the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL. Since the group seized control of the key Sunni cities of Fallujah, Ramadi and Mosul in 2014 until its territorial defeat in December 2017, it has been combatted by a combination of Iraqi Security Forces (ISF), Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU), Kurdish Peshmerga and the United States-led Combined Joint Task Force–Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF–OIR). Since December 2017, the Iraqi government has faced insurgent attacks from ISIS networks concentrated mainly in central and northern provinces and, to a lesser extent, in Anbar in the west. The rate of ISIS attacks increased markedly in 2020, culminating in a high-profile attack (HPA) on 21 January 2021 in Baghdad’s Tayaran Square. The coronavirus pandemic, the first wave of which hit Iraq in February 2020, exacerbated existing drivers of conflict, particularly on the economic front, creating new strategic opportunities which ISIS sought to exploit.

Tensions also increased along other dimensions of conflict during the year. Of note, the Iran–United States confrontation in Iraq escalated following the assassination by the US of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani in January 2020. In response, Iran-aligned Shia militia groups (SMGs) escalated a campaign of indirect fire (IDF) and improvised-explosive-device (IED) attacks on US and CJTF–OIR targets, leading the US to threaten an immediate withdrawal of its Baghdad embassy in late September 2020. A unilateral and conditional ceasefire by SMGs followed. However, attacks picked up following the victory of Joe Biden in the November 2020 US elections as brinkmanship began over returning to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action’s (JCPOA) nuclear agreement with Iran.

In northern Iraq, Turkish air and artillery strikes against Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) positions, mainly in Dohuk, also increased in 2020. Meanwhile, PMU leadership continued to criticise the Sinjar agreement between the Kurdistan regional government and the government of Iraq which had been signed on 9 October 2020.1 Part of the agreement was intended to deal with the contentious presence of PKK militants in the strategic western sector of Nineva province. The issue has become a further point of contention between Turkey and Iran: Turkey seeks to eliminate PKK forces and suspects Iran and its PMU allies of cooperating with the PKK in the sector to preserve Iran’s land bridge to Syria. On 13 February 2021, local media reported that an additional three PMU brigades had been deployed to Sinjar following an announcement by Hadi al-Ameri, the leader of Fatah and the Badr Organisation (and therefore one of the most prominent Iran-aligned Shia Islamist figures in Iraq) that PMU forces would resist what he described as an imminent Turkish military incursion into the area.2

Finally, in central and southern Iraq, SMGs and the ISF used considerable violence to confront activists connected to a protest movement that had emerged in October 2019. Several HPAs on demonstrators resulted in mass casualties, while sporadic kidnap, assassination and intimidatory IED and small-arms-fire (SAF) attacks targeting activists persisted throughout the year, particularly in protest hotspots such as Baghdad, Dhi Qar and Basra.

Conflict Parties

Iraqi Security Forces (ISF)

Strength: 193,000.

Areas of operation: All areas of Iraq excluding the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI).

Leadership: Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi (commanderin-chief); Abdul Amir Rashid Yarallah (army chief of staff);Jummah Enaad al-Jibori (minister of defence); Othman al-Ghanmi (minister of interior).

Structure: The Iraqi armed forces consist of the army, air force and navy. In the fight against ISIS, the army has cooperated with the Federal Police and the Ministry of Interior (MoI) intelligence (the Federal Investigation and Intelligence Agency, Falcons Cell), the Counter-Terrorism Service (CTS), PMU, and other intelligence organs. The army reports to the Ministry of Defence, the Federal Police to the MoI and the CTS to the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO).

History: The capture of Tikrit and Mosul by ISIS in 2014 led to the partial disintegration of Iraqi forces. The forces have been rebuilt with the assistance of the US-led coalition but remain insufficiently equipped for counter-insurgency tasks.

Objectives: Defeat ISIS and ensure security across the country. Since the territorial defeat of ISIS, Iraqi forces have focused on eliminating remaining cells in rural areas. The armed forces also play a role in providing security in the provinces to tackle tribal fighting, protest-related violence and criminality.

Opponents: ISIS.

Affiliates/allies: Kurdish Peshmerga, CJTF–OIR, PMU, CTS.

Resources/capabilities: A range of conventional land, air and naval capabilities including armoured fighting vehicles, anti-tank missile systems, artillery and fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft.

Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU)

Strength: Approximately 100,000.

Areas of operation: Areas previously held by ISIS including Anbar, Nineva, Diyala and Salahaddin provinces, and areas of southern Iraq, particularly Jurf al-Sakhar in Babil province, and shrine cities of Najaf, Karbala and Samarra (north of Baghdad).

Leadership: The PMU has a distinct chain of command from the rest of the ISF. Formally under the PMO and technically directly answerable to the prime minister, de facto leadership of the organisation had resided with the PMU Commission’s chief of staff (formerly Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis). The latter’s assassination in 2020 triggered a leadership struggle. Kataib Hizbullah (KH) commander Abdul-Aziz al-Muhammadawi (also known as Abu Fadak) was elevated to lead the organisation, although power is thought to operate more via a committee of senior figures. However, some PMU brigades loyal to Najaf-based Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani split from the PMU Commission altogether and re-formed as a separate entity answerable to the PMO. Moreover, various groups within the PMU have a high degree of operational autonomy, such as the Sadrists, Saraya al-Salam, the Badr Organisation and Asaib Ahl al-Haq.

Structure: Approximately 40–60 paramilitary units under the umbrella organisation. Formally, the PMU are a branch of the Iraqi security apparatus, but each unit is organised around an internal leader, influential figures and fighters.

History: Formed in 2014 when Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani called upon the Iraqis to protect their homeland against ISIS, the PMU brought together new and pre-existing groups. In 2016, the units were formally recognised as a branch of the Iraqi security apparatus.

Objectives: Initially, to fight ISIS. Some units have evolved into hybrid entities seeking political power. Also functions as an effective counter-protest force and seeks to use violence and coercion to intimidate political rivals. All groups are committed, at least nominally, to expelling US and foreign forces from Iraq. Rising tensions with Turkey have also been noted, with a rocket attack on the Turkish military base near Mosul (Zilkan) in April 2021 attributed to PMF groups.

Opponents: ISIS, US and allied forces, Turkey.

Affiliates/allies: ISF, IRGC.

Resources/capabilities: Capabilities differ between units. Those supported by Iran receive arms and training from the IRGC, including heavy weapons and small arms.

Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL

Strength: Approximately 10,000 in Iraq and Syria, including members and fighters.3

Areas of operation: Active predominantly in Iraq’s northern and central provinces in mountainous and desert areas. Most attacks in 2020–21 occurred in the governorates of Anbar, Baghdad, Diyala, Kirkuk, Nineva, Salahaddin and Babil.

Leadership: Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi (caliph and leader of ISIS). Jabbar Salman Ali Farhan al-Issawi, also known as Abu Yasser al-Isawi (deputy caliph and senior commander in Iraq), was killed by an airstrike in January 2021.

Structure: ISIS operates as a covert terrorist network across Iraq, using a largely autonomous sleeper-cell structure. The organisation continues to have meticulous bureaucratic structures, internal discipline and robust online presence and financial systems.

History: Originated in Iraq around 2003 but proclaimed itself a separate group from al-Qaeda in Iraq, fighting to create a caliphate during the Syrian civil war. Between 2014 and 2017, ISIS controlled extensive territories and governed more than eight million people in Syria and Iraq. It has now lost all its territory, since 2017 in Iraq and since March 2019 in Syria.

Objectives: ISIS continues to fight and project ideological influence globally. In Iraq it operates through decentralised, guerrilla-style insurgent tactics, with hit-and-run attacks, kidnappings and killing of civilians, and local tribal and political leaders, as well as targeted assassinations of members of the ISF.

Opponents: ISF, Kurdish Peshmerga, PMU, CJTF–OIR.

Affiliates/allies: ISIS fighters in other countries.

Resources/capabilities: Carries out attacks through shootings and explosions, using small arms, cars, IEDs, suicide vest improvised explosive devices (SVIEDs), suicide-vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs) and mortar bombs.

Kurdish Peshmerga

Strength: Approximately 150,000 personnel.

Areas of operation: KRI.

Leadership: Nechirvan Barzani (commander-in-chief), Shoresh Ismail Abdulla (minister of Peshmerga affairs), Lt-Gen. Jamal Mohammad (Peshmerga chief of staff).

Structure: A Kurdish paramilitary force, acting as the military of the Kurdistan regional government and Iraqi Kurdistan. While remaining independent, operates officially as part of the Kurdish military system. Split between political factions, the dominant ones being the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan.

History: Began as a Kurdish nationalist movement in the 1920s and soon developed into a security organisation. Following the ISIS advance, the Peshmerga took disputed territories in June 2014 – including Kirkuk – which were retaken by the ISF in October 2017.

Objectives: Ensure security in the KRI, including fighting ISIS.

Opponents: ISIS, PKK.

Affiliates/allies: CJTF–OIR, ISF.

Resources/capabilities: Poorly equipped, lacking heavy weapons, armed vehicles and facilities. The US has provided some financial assistance and light weapons such as rifles and machine guns.

Turkish Armed Forces (TSK)

Strength: 1,000 personnel unilaterally deployed in Iraq (+ 30 under the aegis of NATO Mission Iraq (NMI)).

Areas of operation: Northern Iraq, especially Dohuk and Nineva plains. Currently engaged in Operation Claw-Tiger against the PKK in the Haftanin region. Maintains Zilkan base in Nineva.

Leadership: President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (commander-in-chief); General (retd) Hulusi Akar (minister of national defence); General Yasar Guler (chief of general staff).

Structure: Turkish army units operating under the Turkish Land Forces Command and squadrons carrying out airstrikes operating under the Air Force Command are subordinate to the chief of general staff; gendarmerie units reporting to the Gendarmerie Command are subordinate to the Ministry of Interior.

History: Rebuilt after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1922. Significantly restructured after the country joined NATO in 1951, to become NATO’s second-largest armed force.

Objectives: Combat the PKK and their allied forces and prevent them from establishing safe havens and mobility corridors in northern Iraq; prevent PMU from overrunning Sinjar and establishing a land corridor to Syria for Iran.

Opponents: PKK, Sinjar Alliance, PMU.

Affiliates/allies: Miscellaneous local militias, such as those connected to the Iraqi Turkmen Front who received training from Turkish special forces from 2015.

Resources/capabilities: Turkey’s defence budget for 2020 was US$10.88 billion. Its military capabilities include air attack and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) assets such as the F-16 and the Bayraktar TB2 uninhabited aerial vehicle (UAV), armoured tanks and special-forces units.

Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK)

Strength: 30,000 (estimate) in Turkey and Iraq.

Areas of operation: Sinjar, northern Iraq.

Leadership: Abdullah Ocalan (ideological leader, despite his imprisonment since 1999); Murat Karayilan (acting leader on the ground since Ocalan’s capture); Bahoz Erdal (military commander).

Structure: While operating under the same command and leadership, the PKK’s armed wing is divided into the People’s Defence Forces (HPG) and the Free Women’s Unit (YJA STAR).

History: Founded by Ocalan in 1978. Engaged in an insurgency campaign against the TSK since 1984.

Objectives: Preserve its operational autonomy and capacity with a base of operation in Iraq to support its broader agenda in Turkey.

Opponents: TSK.

Affiliates/allies: Sinjar Alliance in Iraq.

Resources/capabilities: Relies on money-laundering activities and drug trafficking to generate revenues, in addition to donations from the Kurdish community and diaspora and leftwing international supporters. The PKK relies on highly mobile units, using guerrilla tactics against Turkish military targets.

Combined Joint Task Force–Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF–OIR)

Strength: The exact number of coalition forces (including advisers, special forces, etc.) in Iraq is unknown, but the US, the largest component of the coalition, has been repositioning its forces, handing over Iraqi bases to the Iraqi government, and drawing down its overall force commitment. However, the new Biden administration announced that it was reviewing the previous administration’s decisions to withdraw forces from Iraq.

Areas of operation: Working in tandem with the ISF in areas previously held by ISIS, including Anbar, Diyala, Nineva and Salahaddin.

Leadership: Marine Gen. Kenneth ‘Frank’ McKenzie (US Central Command).

Structure: The US leads the CJTF–OIR, which brings together over 20 coalition partners.

History: Established in October 2014 when the US Department of Defense formalised ongoing military operations against ISIS.

Objectives: Fight ISIS in Iraq and Syria, through airstrikes in support of Iraqi and Kurdish forces. Ground forces are deployed as trainers and advisers.

Opponents: ISIS, PMU.

Affiliates/allies: ISF, Kurdish Peshmerga.

Resources/capabilities: Air support (airstrikes complementing military operations by Iraqi armed forces)and artillery.

Other conflict parties

A number of other conflict parties active in the country should also be mentioned. The Sinjar Alliance, affiliated with the PKK, was created in 2015 after the 2014 Sinjar massacre and aims at establishing an autonomous Yazidi region in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The NATO Mission Iraq (NMI) was established in 2018 and currently comprises around 500 staff officers, advisers and support staff (to be incrementally increased to 4,000 following a request by the Iraqi government approved by NATO in February 2021).4 It focuses solely on training and logistical support to the ISF to combat ISIS. NMI supports and supplements the CJTF–OIR training in Iraq.

Iran maintains a significant role in the command-and-control structure of the PMU. Its military presence in Iraq is primarily covert: senior officers of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force (IRGC-QF) have served as advisers to the ISF as well as PMU commanders, and Iran has deployed niche military capabilities during the fight against ISIS. The IRGC-QF maintains a privileged relationship with several PMU militias, notably Kataib Hizbullah, Asaib Ahl al-Haq, the Badr Organisation, Harakat Hizbullah al-Nujaba and their splinter groups. These factions have conducted operations against Iraqi and Western targets at Iran’s behest.

Conflict Drivers

Political

Patronage, corruption and sectarianism:

Iraq has a patronage-based system of government built on oil revenues. The political elite uses oil rents to reward allies and pursue personal projects, as opposed to funding public goods and services. Coveted jobs in the public sector are awarded based on party connections or in response to public discontent that has manifested in protests. Consequently, the legitimacy of central government has been eroded while resources have been diverted from the reconstruction and development of Sunni areas affected by the ISIS campaign. This has further fuelled militia recruitment, while degrading the competence and fighting efficacy of the ISF. The patronage system also encourages sect-based mobilisation as most parties are organised along Shia, Sunni or Kurdish lines. More recently, the treatment of Sunni internally displaced persons (IDPs), the flawed justice of Iraq’s anti-terrorism legislation and legal processes, and human-rights abuses by victorious Shia militants, have all contributed to Sunni discontent and driven recruitment for ISIS.

Economic and social

Fiscal pressures:

A fiscal budget crisis triggered by the coronavirus pandemic and falling global oil prices exacerbated the structural factors just outlined. The pandemic also disrupted non-oil-based economic activity, particularly for informal workers in contact-intensive sectors. As a result, despite a modest recovery of oil prices in early 2021, Iraq’s economic outlook remains negative. According to the IMF, GDP contracted by 10.9% in 2020, with growth in 2021 forecast at only 1.1%.5

The Central Bank of Iraq (CBI) undertook a controlled currency devaluation in late December 2020 – a measure that had not been adopted for decades. Devaluation led to rising inflation almost overnight in a country that relies heavily on imports of basic goods. When combined with unemployment, delayed infrastructure projects and reduced investment in public services, this is likely to drive both violent anti-government demonstrations and insurgent activity. Moreover, the short-term tactic pursued by previous Iraqi governments of circumventing protests by offering public-sector jobs had built up further structural rigidities in Iraq’s finances.However, the current Iraqi government will have less recourse to such a strategy, due in part to the additional fiscal pressures created by the coronavirus pandemic.

Source: IISS

International

Geopolitical rivalries:

Geopolitical rivalries have eroded Iraq’s capacity to build a coherent, unified state and security apparatus. The Iran–US and regional rivalries have contributed to the proliferation of non-state paramilitaries that challenge the government’s monopoly over the legitimate use of force in its territory. Iran and the US vie for influence over Iraq’s political institutions and security forces, even running competing networks within the MoI. This fragmentation of the Iraqi state erodes its capacity to confront challenges posed by both insurgents and SMGs and to enact political reforms.

Iran–US tensions continued to drive conflict in Iraq during 2020. The Trump administration’s so-called ‘maximum pressure’ strategy against Tehran sought to isolate Iran, while the Abraham Accords in September 2020 (between Israel and Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates) were intended to facilitate cooperation between Iran’s main regional rivals. As a result, Iraq became increasingly important to Iran as an economic outlet, for access to dollars and for sanction-busting oil exports. At the same time, Iran, and its Iraqi allies, sought to retaliate against the US by politically and militarily targeting its military and diplomatic presence in Iraq, and to intimidate those–including the new Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi – considered too close to the US.

Elsewhere, Turkish–Iranian rivalries increasingly played out in northern Iraq and the Sinjar area, with Iran criticising Turkey’s military presence in both Syria and Iraq, viewing its campaign against PKK militants and the struggle for influence in Nineva as threats to its own influence in the area and its land bridge to Syria.

Political and Military Developments

A new prime minister

On 6 May 2020, Mustafa al-Kadhimi was appointed Iraq’s new prime minister. Kadhimi, formerly the head of the Iraqi National Intelligence Service (a Western-aligned intelligence agency) and widely regarded as espousing a fairly pro-US viewpoint, came to office promising to respond to the demands of the October 2019 protesters, such as holding early elections in June 2021. He also sought to rebalance Western and Iranian influence in Iraq, particularly by reshuffling senior security posts in the MoI along with other intelligence agencies and Iraqi Army commands at the provincial level. Kadhimi also engaged in a Strategic Dialogue with the US, which was heralded as an opportunity to ‘reset’ Iraq–US relations, deepen economic and cultural ties, and place the US military presence in the country on a firmer legal and practical footing. However, these talks sparked a backlash from Iran-aligned elements, with a series of assassinations, including Kadhimi’s friend and adviser Hisham al-Hashimi in July 2020 and against activists in Basra during August 2020.

ISIS insurgency

The reporting period saw a modest resurgence in ISIS activity in Iraq, culminating in the 21 January 2021 twin SVIED attack on a clothing market in Baghdad’s Tayaran Square, resulting in several casualties in the first significant breach of the city’s security perimeter by ISIS since 2018. Shortly after, ISIS militants clashed with the PMU in the vicinity of al-Ayth, Salahaddin.

However, aside from these HPAs, Sunni-insurgent-group (SIG) activity remained largely constrained to sabotage, asymmetric hit-and-run SAF and IED attacks on the ISF, and assassinations and kidnappings to raise funds and prevent cooperation between local populations and the Iraqi government. These activities were largely confined to remote desert regions, and difficult-to-secure spaces such as the Hamrin Mountains, the Makhoul Mountains, the Diyala–Salahaddin border, southern Nineva and western Anbar province. ISIS also continued to exploit disputed territories and mixed-sect areas such as Diyala and Kirkuk. Meanwhile, ISIS activity in southern Iraq was constrained to infrequent probing hit-and-run SAF and IED attacks on PMU positions in Jurf al-Sakhar.

On 22 January 2021, Iraq’s CTS responded to the Baghdad attack by launching Operation Revenge of the Martyrs. Of note, an airstrike in Zaidan, Abu Ghraib, killed four insurgents including the ISIS ‘Emir of southern Iraq’, Abu Hassan al-Gharibawi. Meanwhile, a further airstrike killed the leader of the Islamic State in Iraq, Jabbar Salman Ali Farhan al-Issawi, in the vicinity of Kirkuk.

Iran–US conflict

An escalating military campaign against CJTF–OIR interests in Iraq followed Soleimani’s assassination in January 2020. Of note, two IDF incidents on Camp Taji (north of Baghdad), on 11 and 14 March, resulted in fatalities and injuries to coalition forces. In response, the US launched airstrikes against KH facilities in Babil, Karbala and south of Baghdad.Nevertheless, Western interests in Iraq continued to face hostile IDF from SMGs, focused mainly on the US Embassy compound in the International Zone. An escalating campaign of IED attacks also targeted logistics convoys contracted to the CJTF–OIR on the main supply routes through Dhi Qar, Diwaniyah, Babil and Baghdad.

In response, the US threatened to close its embassy in Baghdad in late September 2020, leading to panic among the Iraqi political class and the declaration of a unilateral ceasefire by SMGs. However, hostilities escalated again after the victory of Joe Biden in the November 2020 US elections as Iran and its Iraqi proxies sought to pressure the US administration to return to the JCPOA without preconditions or caveats. This culminated in the 15 February 2021 IDF attack on the US military base at Erbil International Airport, claimed by an SMG. The Biden administration opted for a restrained response, launching airstrikes against KH targets in Al-Bukamal, Syria, and leaving open a possible pathway to JCPOA compliance.

Splintering within the PMU

In April 2020, several factions of the PMU loyal to Najaf-based Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani split from the PMU Commission. The brigades – Kataib Imam Ali, Ali al-Akbar, Abbas and Ansar al-Marjaiya – henceforth reported directly to the PMO. The move reflected discontent within the PMU at the efforts to install a KH commander, Abu Fadak, as de facto PMU chief following the assassination of Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis. Overall, the move by the so-called ‘shrine’ militias reflected broader fragmentation within the PMU/SMG structure following the removal of its central pillars (Soleimani/Muhandis).Soleimani’s replacement, Esmael Qaani, focused on building his own support base within Iraq’s SMGs, sponsoring the proliferation of new ‘splinter’ groups that broke off from more established factions and organised around the KH network. These new splinter groups have claimed responsibility for the majority of IED and IDF attacks on US and CJTF–OIR targets in Iraq between February 2020 and February 2021.

Regional competition in northern Iraq

Turkey continued to pursue PKK militants in northern Iraq, launching dozens of raids, airstrikes and artillery strikes. Most of this activity was concentrated in the mountainous regions of Dohuk, although operations were also noted in the northern sectors of Erbil, Sulaymaniyah and Nineva. Iran and Turkey also clashed over the Sinjar agreement, with Turkey suspecting that the Iran-aligned PMU were cooperating with PKK elements in Sinjar to preserve Iran’s land bridge to Syria through the territory. In early February 2021, it was reported that PMU units had been moved to the area after receiving intelligence pointing to an imminent Turkish military operation against Sinjar.

Key Events in 2020–21

POLITICAL EVENTS

3 January 2020

Soleimani and Muhandis are assassinated by the US in a Baghdad airstrike.

24 January

Sadrist protesters in Baghdad condemn the killing of Soleimani and Muhandis and demand the withdrawal of the US presence in Iraq.

5 February

Sadrist paramilitaries begin attacking protesters in Najaf and Karbala following the announcement that Muqtada al-Sadr was withdrawing his forces from the October 2019 protest movement.

15 February

Iraq begins imposing strict COVID-19 mitigation measures including curfews and restrictions on public gatherings as case numbers rise.

6 May

Kadhimi becomes Iraqi prime minister, succeeding Adil Abdul-Mahdi who resigned in November 2019 in response to the October protest movement.

August

Kadhimi visits Washington DC to conclude the Strategic Dialogue talks with the US.

October

Activists attempt to rejuvenate the nationwide protest movement that had erupted in October 2019 on the one-year anniversary of the protests.

28 October

The Economic Contact Group (composed of the G7 countries, the IMF and the World Bank) holds its first session in the United Kingdom. The group intends to coordinate financial and technical support for Iraq to help the country respond to the coronavirus pandemic, economic crisis and ongoing war against ISIS.

20 December

The CBI undertakes a controlled (almost 20%) devaluation of the Iraqi dinar against the US dollar, prompting some limited protest activity.

MILITARY/VIOLENT EVENTS

April 2020

Several factions of the PMU loyal to Najaf-based Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani split from the PMU Commission.

6 July

Prominent Iraqi security analyst and friend and adviser to Kadhimi, Hisham al-Hashimi, is assassinated in Baghdad by a suspected SMG.

September

In response to escalating attacks on its diplomatic and military interests, the US threatens to close its embassy in Baghdad.

21 January 2021

A twin SVIED attack on a clothes market in Tayaran Square, Baghdad, kills dozens and injures over 100.

18 February

NATO announces an expansion of its security training mission in Iraq, from circa 500 to 4,000 troops, on the back of a partial drawdown of US forces in January (from 3,000 to 2,500).

25 February

US launches strikes against Iranian militias in Syria, who were responsible for attacks on US troops in Erbil.

Impact

Human rights and humanitarian

The ISIS insurgency continues to feed on the marginalisation of Iraq’s Sunni community, particularly in areas affected by displacement or where local populations suffer abuses by Shia armed groups. There is also widespread belief in these areas that corruption has delayed reconstruction projects or siphoned off their funding. Other specific forms of discrimination, such as punitive counter-terrorism legislation and inadequate due process in terrorism-related trials, all pose a risk of future radicalisation.

Attacks on humanitarian workers in Iraq are relatively rare as most combatants (excluding the Islamic State) have an interest in seeing international-development and aid projects continue for political and financial reasons. However, intimidation, assaults and arrests against aid workers have been documented in Sunni IDP camps and in areas previously under ISIS control, along with accusations that aid workers are supporting ISIS. Elsewhere, a small number of incidents involving attacks on international aid workers were attributed to SMGs.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, more than 3m Iraqis have been displaced across the country since the war with ISIS escalated in 2014.6 This group has faced multiple humanitarian challenges including extreme poverty, mass executions, systematic rape and other human-rights abuses.7 As of late 2020, the Norwegian Refugee Council estimated that there remained at least 240,000 IDPs inside Iraq. In October 2020 the Iraqi government moved to shut down IDP camps, fearing that they may become institutionalised and function as a haven of militants and insurgent recruitment, and resettle or relocate IDPs. However, aid agencies warned that rushing to move IDPs to other camps or to communities that lacked the infrastructure and support networks to reintegrate displaced persons risked harming IDPs further.8

Political stability

Political and economic stability continues to be undermined by the country’s fragmented politics, which makes addressing many of the structural drivers of conflict more difficult. Compounding this, Kadhimi lacks his own political bloc in parliament, meaning he is forced to cut deals and balance between the various political factions to advance his policy agenda. Kadhimi proposed a plan for public-sector cutbacks designed to secure IMF budgetary assistance in a so-called ‘White Paper’ on economic reform.9 However, Iraq’s political class has repeatedly refused to countenance salary or pension cuts for public-sector employees. With an eye on forthcoming elections in 2021, politicians are reluctant to take ownership of unpopular austerity measures, especially at a time of rising inflation. Moreover, the Iraqi parliament, the Council of Representatives (CoR), has effectively had limitless power to rewrite the budget-proposal draft submitted by the government. Whereas the Federal Supreme Court had previously ruled as unconstitutional amendments made by members of parliament to Iraq’s federal budget law because they diverged too radically from the original text submitted by the Council of Ministers (CoM), it cannot currently mount such a challenge as it lacks a quorum. As a result, the CoM’s agenda for economic reforms was largely dismantled in the CoR by February 2021.

Relations with neighbouring and international partners and geopolitical implications

Kadhimi has sought to rebalance Iraq’s relations with its neighbours and between Iran and the US. This has involved reshuffling senior security posts in the MoI, army, CTS and various Iraqi intelligence agencies. In part, these moves were designed to reassure the US of the seriousness of the Iraqi government’s intent to reduce Iranian influence in the country’s security apparatus. Kadhimi’s outreach to the US during the Strategic Dialogue and his refusal to act upon the CoR’s January 2020 vote to expel US forces provoked opposition from both powerful Shia Islamist factions in Iraq and Iran, who are keen to see Kadhimi replaced by a less antagonistic figure.

On the economic front, the government has been keen to build bridges with Iraq’s Sunni neighbours, signing economic agreements with Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, and making progress on a plan to connect the Iraqi and Saudi electrical grids. Nevertheless, Iraq remains highly dependent on energy exports from Iran and Kadhimi has repeatedly been forced to back down from significant confrontations with Iran-backed groups who have directly challenged his authority.

Conflict Outlook

Political scenarios

Various obstacles forced Kadhimi to postpone the early elections – initially scheduled for June 2021 – until October 2021, although many observers and Iraqi politicians expressed doubt over whether this postponed date will be met. The main obstacles to early elections include the lack of a quorum on the Federal Supreme Court, funding for the Iraqi Higher Electoral Commission, the registration and distribution of biometric data (particularly difficult for areas impacted by ISIS and high levels of displacement), and the resurgence of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2021.Should elections go ahead, the new electoral law (initially ratified in December 2019 but still subject to debate), which radically alters how elections in Iraq are conducted, is widely expected to be of most benefit to the Sadrist movement given its unique powers of local mobilisation.

Various new parties have emerged to represent the October 2019 protest movement. Of note, Imtidad, led by prominent Dhi Qar activist Alaa al-Rikabi, has attempted to mobilise the Iraqi youth as an untapped electoral demographic. However, it is unlikely that they will make significant electoral gains, given the fragmented nature of protest politics, voter apathy and the ability of the existing elite to shore up its position through violence and economic patronage.

Since the fall of Nouri al-Maliki in 2014, Iraq’s political class has preferred to keep power dispersed, dividing up the state and its resources in such a way that has prevented intra-elite conflicts escalating into violence. This tends to preclude the emergence of a dominant power centre that could drive political or economic change: this mode of politics is highly likely to persist following the elections. Thus, the Sadrists’ increased political influence will probably be somewhat offset by bandwagoning amongst other factions. In any event, the prime ministership, ministerial positions and directors general (senior civil-service positions) will continue to be divided among the main political blocs via backroom postelections negotiations. The outcome will most likely be agreement on another compromise candidate for prime minister with little autonomous power who will not threaten the core interests of the main political factions. As a result, there is little prospect of the Iraqi government pushing through meaningful political or economic reforms, particularly if these require approval by the CoR. Instead, Iraq’s political class will likely hope to hold the state together until oil prices rebound.

However, even in this scenario, given the fiscal overextension of the state, spending on investment in services, development, reconstruction and humanitarian programmes will probably have to fall. Meanwhile, the state’s capacity to absorb increasing numbers of unemployed youth into the public sector will also be more constrained. This scenario is likely to drive localised and national discontent across Kurdish, Sunni and Shia provinces, fuelling insurgent activity and protests alike.

Escalation potential and conflict-related risks

ISIS networks are likely to continue to expand their operations in remote and difficult-to-secure regions of Iraq, taking advantage of political inertia at the heart of the Iraqi political system, and the discontent in Sunni communities over corruption and human-rights abuses. Nevertheless, HPAs in highly populated locales are unlikely, provided cooperation continues between key Iraqi security organs (primarily the CTS and the MoI’s Falcons Cell) and the CJTF–OIR, along with supportive airpower. The late February 2021 news that NATO was significantly expanding its advisory mission to Iraq indicates that the new US administration and its allies remain somewhat committed to cooperating to contain an ISIS resurgence, despite Washington also wanting to reduce its exposure in Iraq.

As seen in recent years, the Iraqi state and its parastatal armed factions have also become increasingly adept at deploying violence to quell protesters. However, such violence carries the risk of escalation, particularly if local (heavily armed) tribes engage on one side or another of the confrontation between protesters, the ISF and militias. A potential for violent escalation and a multidimensional – albeit localised – conflict involving these different parties cannot be discounted, particularly in hotspots for violent protest dynamics, most notably in Dhi Qar.

Strategic implications and global influences

The US–Iran conflict in 2021 will revolve around attempts to choreograph a return to the JCPOA, which is the stated objective of both sides. However, while the US and its allies continue to demand that Iran comply with the agreement before any lifting of sanctions, and to threaten to impose new conditions relating to Iran’s missile programme and regional proxy wars, Iran is unlikely to de-escalate its attacks on US and allied targets in Iraq. Moreover, Iraq’s so-called ‘resistance factions’ (the main SMGs) are unlikely to intrinsically link US military and diplomatic presence in Iraq to the JCPOA and will seek to maintain a level of hostility against the US and the CJTF–OIR irrespective of progress on the Iran nuclear agreement. Added to this, the Biden administration’s reduced appetite to undertake retaliatory military strikes in Iraq, or other high-risk actions – such as the Soleimani assassination – will likely embolden SMGs to intensify IED and IDF attacks on US-linked targets. This said, agreement on reciprocal confidence-building measures between Iran and the US is likely during 2021, with a return to the JCPOA the most likely scenario by the end of the year. While this may reduce tensions in Iraq, Iran and its Iraqi allies will probably continue to pursue US withdrawal from Iraq via a more gradual war of attrition on US and allied interests in the country.

Notes

- 1 The Sinjar agreement seeks to remove all armed groups from the Sinjar area except for armed forces of Federal Iraq, while Kurdistan regional government was accorded powers to influence local political appointments and to coordinate reconstruction efforts.

- 2 See, for example, Tahsin Qasim, ‘Three PMF Brigades Deployed to Shingal to Counter Turkish Threats’, RUDAW, 13 February 2021; and ‘Al-Amiri Says Turkey Intends to Attack Sinjar Mountains in Iraq’, Iran Press, 14 February 2021.

- 3 ‘Iraq Bombing: IS Says It Was Behind Deadly Suicide Attacks in Baghdad’, BBC News, 22 January 2021.

- 4 Hiwa Shilani, ‘NATO Announces Eight-fold Increase in Number of Forces in Iraq’, Kurdistan24, 18 February 2021.

- 5 International Monetary Fund, ‘World Economic Outlook Database’, April 2021.

- 6 IDPs estimates vary across sources. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) the total number of conflict IDPs amounts to 5.6m since 2014. See IDMC, ‘2020 Internal Displacement’, Global Internal Displacement Database.

- 7 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, ‘Iraq Emergency’, 31 March 2021.

- 8 ‘Iraq’s Decision to Shut Down IDP Camps Too Hasty, NGOs Say’, Al-Jazeera, 16 November 2020.

- 9 Government of Iraq, ‘White Paper for Economic Reform’, 22 October 2020.

ISRAEL–PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES

Source: UN OCHA oPt, White House

Overview

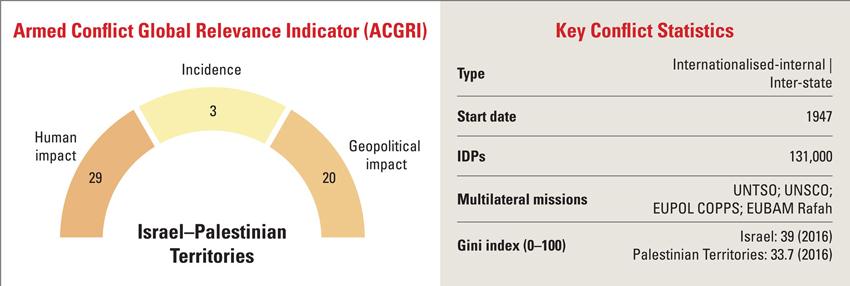

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict began with the outbreak of a civil war between Jews and Palestinian Arabs in British Mandate Palestine on 30 November 1947, a day after the United Nations adopted the partition plan that called for the creation of a Jewish state alongside a Palestinian one. Following the formal ending of the British Mandate in 1948, the conflict was transformed into a multi-state war: after Israel declared its independence on 14 May, the armies of Egypt, Iraq, Syria and Transjordan and contin-gents from other Arab countries attacked the newly founded state. The 1948 Arab–Israeli War resulted in the displacement – including through force – of between 650,000 and one million Palestinians from their homes inside what became the 1948 borders. A further 30,000–40,000 Palestinians were internally displaced within the territory of Israel. As in the case of the Palestinian refugees who were displaced/ expelled beyond the borders of the new state, Israel refused to allow internally displaced Palestinians to return to their homes and villages and designated them ‘present absentees’.1

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War did not end the regional and domestic conflict. In two successive wars (the 1967 Six-Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War), Israel defeated a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria. During the Six-Day War, Israel captured East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, the Sinai Peninsula and the West Bank. The dire socio-economic effects of Israel’s military occupation subsequently led to the outbreak of two Palestinian uprisings – known as Intifadas – in the territories (1987–93 and 2000–05), three Israeli military operations in Gaza (2008–09, 2012 and 2014), and intermittent waves of violence and terrorist attacks.2 Despite the initial buoyancy of the 1993 Oslo Accords, final-status negotiations, as set out in the Declarations of Principals encapsulated in Oslo I, have failed to materialise so far.

The conflict saw no signs of abating in 2020. Israeli–Palestinian political and security coordination was halted mid-year amid threats of an impending unilateral Israeli annexation of West Bank territory but was re-established following the signing of the Abraham Accords, which staved off an official Israeli annexation. Brokered by the United States’ administration, these accords led Israel to establish official, open diplomatic and economic relations with Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – followed by Morocco and Sudan.3 However, Israel’s de facto annexation did not end, as existing settlements were expanded and units that had been built without permits were legalised.

The state of ongoing conflict was compounded by an economic and health crisis resulting from the coronavirus pandemic.Conflict-related inequalities in access to healthcare and diverging financial situations, however, led to disparities in governmental responses. In December 2020, Israel moved quickly to roll out its newly approved coronavirus vaccine, achieving higher inoculation levels than any other country, reportedly receiving an acquisition edge by paying almost twice as much per double-shot dose as the European Union and the US.4 The vaccination programme, as of February 2021, did not fully extend to the Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza, as Israel claimed that the cash-strapped Palestinian Authority (PA) was responsible for its citizens’ healthcare, pursuant to the 1993 Oslo Accords.5

Conflict Parties

Israel Defense Forces (IDF)

Strength: As of 2020, the IDF had a standing strength of about 170,000 personnel, with a further 465,000 in reserve.

Areas of operation: Gaza Strip, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and West Bank.

Leadership: Aviv Kochavi has been chief of staff since 2019.

Structure: The IDF is divided into three service branches: ground forces, navy and air.

History: The IDF was founded in 1948 from the paramilitary organisation Haganah, which fought during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

Objectives: Israel’s defence policy prioritises homeland defence, but its anti-Iran strategy became increasingly overt in 2020, with strikes targeting Iranian positions in Syria and, allegedly, Iraq, to curb Iranian weapons transfers and military build-ups.

Opponents: Hamas, Hizbullah, Iran and Iran-backed groups.

Affiliates/allies: The IDF maintains close military relations with the US. In 2016, the two governments signed a new ten-year Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), covering fiscal years 2019–28, under which the US pledged to provide US$38 billion in military aid to Israel.6

Resources/capabilities: The IDF relies on sophisticated equipment and training. It has a highly capable and modern defence industry, including aerospace; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), and counter-rocket systems. It is also believed to have an operational nuclear-weapons capability, though estimates of the size of such arsenal vary. The IDF can operate simultaneously in West Bank, Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq – usually favouring a clandestine, incursive nature when operating outside the Palestinian Territories.

Hamas

Strength: Hamas’s military wing, the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades (IDQ), is estimated to comprise around 15,000–20,000 fighters trained in urban warfare.

Areas of operation: Gaza Strip, Israel and West Bank.

Leadership: Since 2017, Yahya Sinwar has been head of Hamas; Ismail Haniyeh is chief of the central Political Bureau.

Structure: Hamas’s internal political leadership exercises ultimate authority; other wings and branches, including the IDQ, follow the strategy and guidelines set by Hamas’s Shura Council and Political Bureau, or Politburo.

History: Founded in 1987 by members of the Muslim Brotherhood in the Palestinian Territories, Hamas is the largest Palestinian militant Islamist group. It has been designated a terrorist group by the European Union and the US, but many Palestinians view it as a legitimate popular resistance group.

Objectives: Hamas’s original charter called for the obliteration or dissolution of Israel, but Haniyeh stated in 2008 that Hamas would accept a Palestinian state within the 1967 borders. This position was confirmed in a new charter in 2017, which stated that Hamas’s struggle was with the ‘Zionist project’.

Opponents: Fatah-led PA, Israel, Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) (periodically) and Salafi jihadi groups.

Affiliates/allies: Hamas relies on financial support and arms and technology transfers from its main regional backer, Iran. A 2019 report found that Iran had agreed to increase its funding to Hamas by US$24m a month (to the total tune of US$30m) in exchange for intelligence on Israeli missile stockpiles.7

Resources/capabilities: The IDQ’s capabilities include artillery rockets, mortars and anti-tank systems. Israel’s military actions have periodically degraded the command and the physical infrastructure of Hamas but seemingly have had little effect on the long-term ability of the IDQ to import and produce rockets and other weapons.

Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ)

Strength: The al-Quds Brigades, the armed wing of the PIJ, consists of approximately 6,000 combatants.

Areas of operation: Gaza Strip.

Leadership: Since September 2018, Ziad al-Nakhalah has been in charge of the PIJ.

Structure: The PIJ is governed by a 15-member leadership council. In 2018, in the first elections since 1980, the PIJ elected nine new members to the council, who represent its members in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, Israeli prisons and abroad.

History: The PIJ was established in 1979 by Fathi Shaqaqi and Abd al-Aziz Awda, who were members of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood until the late 1970s.Among the Gaza-based militant groups, PIJ poses the greatest challenge to Hamas’s authority in the Strip and has derailed unofficial ceasefire agreements between Hamas and Israel.

Objectives: To establish a sovereign, Islamic Palestinian state within the borders of pre-1948 Palestine. Since the late 1980s, the PIJ has carried out suicide-bombing attacks and, in the past decade, fired rockets into Israeli territory, at times in coordination with Hamas. The PIJ refuses to negotiate with Israel and does not seek political representation within the PA.

Opponents: Israel and, periodically, Hamas.

Affiliates/allies: The PIJ’s primary sponsor is Iran, which has provided the group with millions of dollars of funding in addition to training and weapons. Since the leadership’s relocation to Damascus in 1989, the Syrian regime has also offered military aid and sanctuary to the PIJ.

Resources/capabilities: The PIJ has increased the size of its weapons cache by producing its own rockets. Nakhalah has stated that the PIJ would have the ability to fire more than 1,000 rockets daily for a month in the event of a new war. Analysts, however, estimate that the PIJ has some 8,000 rockets in its stockpile.8

Conflict Drivers

Political

Settlements:

The occupation of the West Bank in 1967 heralded the beginning of Israel’s settlement policy. The Allon Plan (named after the then Israeli minister of labour Yigal Allon) was based on the doctrine that sovereignty over large swathes of Israeli-occupied territory was necessary for Israel’s defence, creating a so-called ‘Iron Wall’, and became the framework for the settlement policies implemented by successive Israeli leaders. Since then, more than 140 Israeli settlements have been established across the West Bank and East Jerusalem (with circa 640,000 people), despite the fact that settlements are illegal under international law, violating Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.

The PA sees the settlements as proof of Israel’s lack of commitment to a two-state solution, a view reinforced by the fact that settlements continue to proliferate. Some Israeli administrations have attempted to restrict or reverse the movement of settlers: for example, then-prime minister Ariel Sharon forcibly evacuated some 8,800 settlers from the Gaza Strip in 2005.9 However, although the Israeli government stopped approving new settlements in the West Bank in the mid-1990s, dozens of unauthorised outposts have since been established. Constant settlement growth has fragmented and dramatically reduced the territory foreseen for an independent Palestinian state as part of the 1993 Oslo Accords. The two-state solution based on pre-1967 borders has therefore become increasingly difficult to realise.

International

Foreign involvement:

The Israel–Palestinian Territories conflict is by no means a one-dimensional crisis; from its very beginning, foreign actors have been drawn into the conflict, both as mediators and as participants. For instance, in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, similarly to the Six-Day War, Israel faced coalitions of Arab states acting on varying motivations and with divergent objectives. As a result, to this day, Arab- and Muslim-majority nations claim a commitment – if somewhat cursory – to the Palestinian cause and quest for independent nationhood. The Arab Peace Initiative, which was endorsed by the Arab League’s 22 members at the 2002 Beirut Summit, accordingly conditioned Arab normalisation with Israel upon a set of prerequisites: full withdrawal by Israel from the occupied territories; a ‘just settlement’ of the Palestinian refugee problem based on the 1948 UN Resolution 194; and the establishment of a Palestinian state, with East Jerusalem as its capital. Nevertheless, in 2020, in an apparent departure from this premise, Bahrain, Morocco, Sudan and the UAE moved to normalise relations with Israel despite a lack of advancement in the peace process.

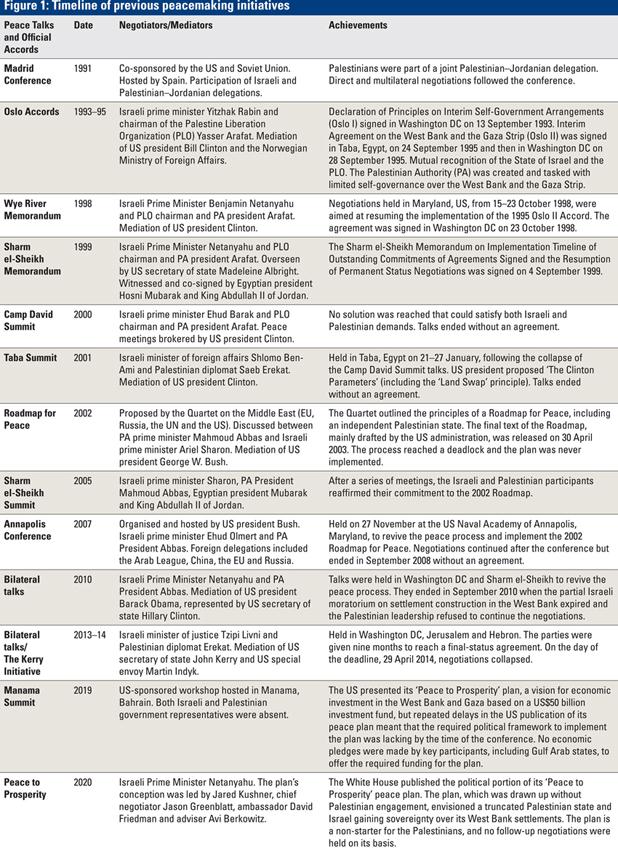

Multilateral mediation has long been considered key to achieving a solution to the Israel–Palestinian Territories conflict. The Madrid Conference of 1991 and the resulting 1993 Oslo Accords, which were premised on conducting future discussions on key ‘final status’ issues, have often been used as a framework for subsequent peace negotiations. The 1993 Oslo Accords also cemented the mediatory role played by outside actors, especially the US, which has traditionally acted as the key broker, often resulting in strengthened or secured Israeli interests. US dominance as a third-party mediator has equally complicated other actors’ formative involvement in peace negotiations, including that of the EU.10 Emblematic of Israel’s ongoing reproval of European foreign-policy heads, the EU has typically been referred to as a ‘payer’ but not a ‘player’ in the aftermath of the 1993 Oslo Accords–regardless of its long-standing commitment to the two-state solution and its continued monetary support for the PA.11

Political and Military Developments

Failed peace negotiations

The 2020 Peace to Prosperity peace agreement drawn up by the Trump administration in January offered a political vision for Israeli–Palestinian peace. In defiance of international law, the political element of this so-called ‘Deal of the Century’ supported Israeli sovereignty over parts of the West Bank, including the Jordan Valley.12 Constructed without Palestinian input or interest, the plan proved a non-starter and, instead, cemented Palestinians’ perception of the Trump administration as an unfit mediator. Future negotiations will be further complicated by the persistent inter-Palestinian political rivalry between Gaza-based Hamas and the West Bank-based PA, in spite of multiple attempts at political reconciliation. Increased diplomatic ties between Israel and the Arab- and Muslim-majority states, meanwhile, challenge Arab claims of support for the Palestinian cause, as laid out in the 2002 Arab Peace initiative, and have heightened Palestinian feelings of international alienation and disenfranchisement. Emblematic of this geopolitical shift, Palestinian leaders were not informed in advance of the 2020 Abraham Accords, and after the news broke the PA ‘accused the UAE of selling them out’.13

No end to Israel's settlements

In late 2020, 441,600 settlers were living in the West Bank across 132 settlements and 135 outposts, constituting approximately 14%of the entire West Bank population.14 In addition, over 220,000 Jews live in East Jerusalem across 13 Israeli neighbourhoods.15 In 2020, settlement expansion and creation continued. In February, the Higher Planning Council of the Civil Administration approved 1,737 housing units in West Bank settlements. This announcement followed the unveiling of the political portion of the Trump administration’s peace plan. The Peace to Prosperity plan, unveiled in late January 2020, offered endorsement for a de facto Israeli annexation of parts of the West Bank, backing a 2019 election pledge by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Netanyahu, however, ultimately shelved these plans as part of the Abraham Accords.

While the Abraham Accords might have temporarily halted a unilateral Israeli annexation of West Bank territory, de facto Israeli annexation practices continued in 2020, in part to bolster Netanyahu’s support among the right wing amid his legal woes and alleged mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic. Peace Now, which began recording statistics in 2012, reported that Israel approved or forwarded construction of over 12,000 settlements in 2020, the highest annual number on record.16 Meanwhile, data compiled by Israeli human-rights group B’Tselem showed that between January and September 2020 at least 741 Palestinian homes were demolished by Israeli authorities on the grounds of lacking building permits – the highest statistics since 2016.17 In early January 2021, on the eve of Joe Biden’s assumption of the US presidency, Netanyahu approved the construction of 800 new housing units in Jewish settlements in the West Bank. This move set the stage for further tension between the Israeli prime minister and the new US president, as Biden is expected to reverse course from his predecessor and adopt the traditional American stance of opposing settlement constructions.

Daily violence and military clashes

Violent clashes between Israelis and Palestinians occurred – if mostly on a limited, small scale – both in the West Bank and Gaza. In August 2020, in a reported attempt to pressure Israel to ease its economic blockage of Gaza, Hamas fired rockets towards Israel, which responded with airstrikes on the Strip. A Qatari-mediated ceasefire agreement, reached in late August 2020, came to an end in December when Israeli air raids targeted Hamas positions in Gaza. A UN report found that between January and October 2020, Israeli forces carried out 42 incursions in Gaza, causing damage to agricultural land and vegetation.18 The Gaza Ministry of Agriculture reported that damages exceeded US$32,000.19

In the West Bank, Palestinians and Israelis were embroiled in repeated confrontations. 2020 witnessed a surge in settler and Jewish extremist violence targeting Palestinians, reportedly spiking by 78%between 17 and 30 March compared to the same period in 2019.20 Settler violence also claimed Israeli victims. A January 2021 Haaretz article documented an increase in settler attacks aimed at Israeli soldiers and police officers in the West Bank; 2020 saw 42 instances of such attacks compared to 29 in 2018.21 Israeli forces and Palestinian civilians also frequently engaged in violent confrontations. In October, IDF troops clashed with Palestinians at al-Amari refugee camp, leaving 53 Palestinians injured, according to reports by the Red Crescent.22 B’Tselem found that Israeli security forces were responsible for the deaths of 23 Palestinians over the course of 2020 in the West Bank, including six children.23

Key Events in 2020–21

POLITICAL EVENTS

28 January 2020

The Trump administration releases the Peace to Prosperity plan that strongly favours Israel. It proves a non-starter.

22 March

Gaza confirms two cases of COVID-19, raising fears about how the besieged territory’s overstretched health system will cope. The PA imposes a curfew in the West Bank to curb the spread of the coronavirus.

20 April

Netanyahu and his political rival, Benny Gantz, sign an agreement to form an emergency unity government to tackle the pandemic.

19 May

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas announces that Palestinians will no longer abide by security agreements with Israel and the US in response to Israel’s impending threats of annexation of the West Bank.

23 May

Netanyahu, the longest-serving prime minister in Israel’s history, becomes the first serving Israeli prime minister to go on trial. He is charged with bribery, fraud and breach of trust.

September

Israel normalises relations with Bahrain and the UAE, in an accord brokered by the Trump administration.

23 October

Sudan agrees to normalise relations with Israel as part of a deal to be taken off a US State Department list of state sponsors of terrorism.

17 November

The PA, encouraged by Biden’s victory, announces the resumption of security and civil ties with Israel.

10 December

Morocco agrees to establish diplomatic relations with Israel in return for US recognition of the kingdom’s sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara territory.

22 December

Israel’s unity government crumbles after the coalition fails to pass a budget; elections are announced for around March 2021.

1 January 2021

Israel establishes itself as a coronavirus-vaccine powerhouse, giving a first dose of the coronavirus vaccine to more than 10% of its population since vaccination began in late December. At the time, the vaccination plan does not extend to the Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza.

January 26

Biden’s administration announces the restoration of relations with the Palestinians and renews aid to Palestinian refugees.

February 5

The Pre-Trial Chamber of the International Criminal Court (ICC) rules that the court has jurisdiction to investigate suspected war crimes in Palestinian territories occupied by Israel. Israel rejects the ruling, claiming, in part, that Israel is not a party to the ICC and has not consented to its jurisdiction.

MILITARY/VIOLENT EVENTS

31 January 2020

Israeli soldiers and Palestinians clash in the West Bank, with 48 Palestinians and one IDF soldier injured during protests over the newly released Peace to Prosperity plan.

2 February

Israeli military jets and helicopters strike Gaza in retaliation for projectiles fired from the Strip.

6 February

A Palestinian driver rams a car into a group of Israeli soldiers, injuring 14 people.

1–22 April

B’Tselem records 23 settler attacks against Palestinians in the first three weeks of April, in spite of coronavirus-related movement restrictions.

12 May

An Israeli soldier is killed during clashes in the West Bank.

3 July

Dozens of Palestinians are injured during clashes in the West Bank with the Israeli army.

August

Hamas and Israel engage in frequent violent exchanges; Israel launches repeated strikes in response to firebombs and incendiary balloons launched by unidentified Palestinians into southern Israel.

1 September

Hamas announces that it has reached an agreement to cease hostilities with Israel, yet attacks continue.

22 November

The Israeli military conducts a series of air raids on Gaza, causing widespread damage to property.

4 December

During stone-throwing clashes in the West Bank, an Israeli soldier fatally shoots a 13-year-old Palestinian child.

7 December

Clashes in the West Bank village of Qalandia injure six Israeli underground border police and four Palestinians.

26 December

Hamas claims that strikes by the IDF – in response to rocket fire from Gaza – damaged a children’s hospital; Israel denies the charges.

Impact

Human rights and humanitarian

Israel continued to enforce severe and discriminatory measures against Palestinians, including restrictions on the right of movement within the West Bank and travel between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, into East Jerusalem, Israel and abroad. Daily life in the West Bank was further complicated by Israeli road closures, which constitute a method of collective punishment. In January and February 2020, B’Tselem documented the blocking of entrances to five West Bank villages, partly in response to locals throwing rocks at Route 505. These blocks preceded limitations on movement that were imposed on all West Bank residents (by both the Israeli military and the PA) in an attempt to control the spread of the pandemic.24 Restrictions on press freedom and the application of a carrot-and-stick policy by the PA have also sought to curtail Palestinian journalists from exposing societal flaws. Human-rights groups have repeatedly shed light on extra-judicial arrests and the persecution of journalists who are suspected of opposing Fatah-led government policies.25 Egyptian and Israeli restrictions on movement out of Gaza harm the civilian population to an equal extent. These restrictions include limiting approval of permit applications from Palestinians seeking medical treatment outside of Gaza to ‘exceptional humanitarian cases’.

Regular outbreaks of violence between Gaza’s Islamist rulers and Israel, together with infighting among Palestinian factions, have affected public facilities and worsened an already precarious humanitarian situation. Considering the deteriorating health system in Israeli-occupied territory and the ongoing spread of COVID-19, in December 2020 and January 2021 international aid groups called on Israel to ‘maintain health services’ and, in accordance with the Fourth Geneva Convention, provide vaccines to the approximately five million Palestinians in these areas.26 While Israel rejected any legal responsibility, in early February Israeli officials agreed to give a total of 5,000 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine for the inoculation of front-line Palestinian medical workers, claiming the move was ‘a clear necessity’ for Israel’s battle with the pandemic.27 Anxious about delays in access to the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiative, the PA approved emergency usage of the Russian Sputnik V vaccine in January 2021 – offering a soft-power win for Russia and increasing the potential for Russian expansion in the Middle East.28 Nevertheless, financial limitations, in addition to uncertainties regarding vaccine delivery and medical storage capabilities, will continue to challenge the vaccine roll-out. At the same time, it remained unclear to what extent the PA would share its vaccines with Gazan inhabitants and how Israeli-imposed delays would complicate future shipments.29

Economic and social

Failed peace negotiations have hampered any viable Palestinian economic development. Restrictive import and export policies, in addition to the territories’ reliance on foreign aid and Israeli management of Palestinian taxes and import duties, have had a devastating effect on the Palestinian economy. Since 2007, Egypt and Israel have imposed a crippling economic blockade on the Gaza Strip, resulting in a shortage of basic products, including food, medical supplies, fuel and construction materials. A 2020 UN report found that Gaza had suffered losses amounting to US$16.7bn due to the ongoing occupation and economic siege, resulting in serious water and electricity shortages, and endemic poverty and unemployment.30 Gisha, a human-rights organisation, reported that the unemployment rate in Gaza reached 49.1%in the second quarter of 2020, an increase of two percentage points compared to 2019, in part due to the outbreak of COVID-19 and the resulting contraction in economic activities.31 At the same time, the World Bank reported that the share of ‘poor households’ increased to 64%in Gaza, compared to 30%in the West Bank.32 In January 2021, Qatar pledged to continue its funding to the Strip by providing US$360m in an effort to reduce tensions between Israel and Hamas and provide relief to the local economy.33

A reduction in Israeli–Palestinian cooperation resulting from impending threats of Israeli annexation had dire effects on Palestinian fiscal stability in 2020. The UN found that the fiscal crisis derived primarily from a collapse in domestic tax revenues during the coronavirus emergency, but also from the Palestinian government’s refusal in early June to receive maqasa (tax revenues) from Israel.34 Under the 1994 Paris Protocol, which governs Israeli–Palestinian economic relations, Israel is supposed to collect value-added tax, import duties and other taxes on the PA’s behalf and transfer them on a monthly basis. The PA is highly dependent on these tax revenues; they account for approximately 60%of its budget. As a result of this decision, hundreds of thousands of Palestinian civil servants – some 15–20%of the PA’s economy, according to an assessment by the World Bank – did not receive their salaries. In November 2020, the PA announced that it would return to accepting the monthly transfers of taxes. According to Palestinian Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh, the decision to resume contacts with Israel was based in part on confronting the ongoing health crisis.

Conflict Outlook

Prospects for peace

The Israel–Palestinian Territories peace process remains mired in a hazardous stalemate. The ongoing political instability in both Israel and the Palestinian Territories has been compounded by the coronavirus health crisis. At the same time, the ongoing governmental and economic crisis in Israel has pushed the conflict down the order of urgency. Indeed, after the December 2020 collapse of the coalition government between the Blue and White party and Likud over the failure to agree on a national budget in December, new national elections were called for March 2021 – the fourth to take place in just two years. The legally embattled Netanyahu is likely to stress Israel’s vaccine success and recent normalisation with Arab-majority nations to secure his political survival.

The inter-Palestinian political struggle has equally hampered the possibility of any effective mediation. The Fatah–Hamas division, despite repeated brokering attempts by Egypt and other actors, enables Israel and its allies to invoke the ‘no partner for peace’ narrative to justify the absence of mediation. Despite their public, unified opposition against Israeli annexation, a new initiative in 2019 that aimed at ending the Fatah–Hamas split failed to make significant progress in 2020. A democratic solution might resolve the impasse with parliamentary elections scheduled for 2021, along with the first presidential elections in 15 years to be held in July, as announced by Abbas at the start of the year. Recent polls suggest a tight contest. In December 2020, the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research found that 38%would vote for Fatah in parliamentary elections, against 34%for Hamas. The centre also predicted that Hamas would have the edge in a presidential vote, with 50%preferring the Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh and 43%preferring Abbas. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the various parties, in addition to the international community, will enable a fair electoral process and accept the election results.35 Indeed, in early 2021, it was reported that the PA and Hamas were both targeting each other’s supporters in an effort to foil their upcoming election participation.36

Strategic implications and global influences

Faced with an ongoing global health crisis and a focus on near-peer competitors, Israeli–Palestinian peacemaking will not top the international community’s foreign-policy agenda in 2021. Significant challenges will likely prevent the EU from becoming a key player in the conflict in 2021, such as the continuing pandemic, a far-right political surge and its dogged commitment to an ‘illusory status quo ante’.37 Nevertheless, bolstered by a new occupant in the White House and a new EU foreign-policy head, the European bloc is likely to deepen its ‘differentiation policy’ of excluding Israeli settlements from bilateral relations with Israel while pushing for a unified Palestinian engagement.

Bilateral relations between the US, the key Middle East interlocutor, and Israel/the Palestinian Territories are bound to change with the new Biden administration. While the new president is unlikely to prioritise Israel or a new Israeli–Palestinian peace effort, he is expected to return a modicum of credibility and objectivity to US mediation of the Israeli–Palestinian negotiations, following four years of Donald Trump’s unabashedly pro-Israeli policies. An early telling sign, just six days after taking office, was the decision to restore aid to the Palestinians and reinstate contributions to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, the UN agency that provides aid to the Palestinians. Israel’s fractured government, conversely, will need to adapt to a new, downgraded ranking on the list of US foreign-policy priorities. Israelis are bracing for what they believe will be a downturn in relations with Washington; a post-election poll showed that 74%of Israelis believe that the new US administration will be less friendly. This perception, however, does not augur well for renewed peace negations; only 2%of Israelis polled in July 2020, while Trump was still in power, believed that a peace deal would be ‘Very likely’ by 2025.38 With several key US foreign-policy officials signalling an intent to re-enter the Iran nuclear deal, Israel is expected to capitalise on recent normalisation deals with the Arab world in an effort to solidify its anti-Iran campaign while consolidating a domestic status quo.

Notes

- 1 Nihad Boqa’i, ‘Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons Inside Israel: Challenging the Solid Structures’, Palestine–Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture, vols 15–16, no. 3, 2008.

- 2 ‘Gaza Crisis: Toll of Operations in Gaza’, BBC, 1 September 2014.

- 3 ‘Sudan Quietly Signs Abraham Accords Weeks After Israel Deal’, Reuters, 7 January 2021.

- 4 Stuart Winer, ‘Israel Will Reportedly Pay Much More Than US, EU for Pfizer Coronavirus Vaccine’, Times of Israel, 16 November 2020.

- 5 The sustained fighting that broke out in April 2021 and the subsequent ceasefire signed in May are not covered in detail in this report as they fall outside the scope of the reporting period for The Armed Conflict Survey 2021.

- 6 This MoU replaced a previous US$30bn ten-year agreement, which ran until the financial year of 2018. Matt Spetalnick, ‘U.S., Israel Sign $38 Billion Military Aid Package’, Reuters, 14 September 2016.

- 7 Anna Ahronheim, ‘Iran Increases Hamas Funding in Exchange for Intel on Israel’, Jerusalem Post, 8 August 2019.

- 8 Shlomi Eldar, ‘Behind Egypt’s Gift to Islamic Jihad’, Al-Monitor, 21 October 2019.

- 9 Martin Gilbert, The Routledge Atlas of the Arab–Israeli Conflict, (Routledge: Oxford, 2012), p. 170.

- 10 This stance is reflected in various surveys; for example, in the 2018 Israeli Foreign Policy Index of the Mitvim Institute, 55%of the Israeli participants said that the EU is currently more of a foe, compared to 18%who saw it as a friend. An EU poll asked Israelis to describe their country’s relations with the EU, and only 45%responded that they were good. A majority of Israelis also think Brussels is not a neutral actor and the EU is not a strong defender of Israel’s right to exist. See Muriel Asseburg, ‘Political Paralysis: The Impact of Divisions among EU Member States on the European Role in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict’, in Muriel Asseburg and Nimrod Goren (eds), Divided and Divisive: Europeans, Israel and Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking (Israel: Mitvim, 2019), p. 22.

- 11 Herb Keinon, ‘Top EU Foreign Policy Nominee Has Record of Slamming Israel, Praising Iran’, Jerusalem Post, 5 July 2019; Asseburg and Goren, Divided and Divisive: Europeans, Israel and Israeli-Palestinian Peacemaking, p. 37; and Anders Persson, ‘Introduction: The Occupation at 50: EU–Israel/Palestine Relations Since 1967’, Middle East Critique, vol. 27, no. 4, October 2018, pp. 317–20.

- 12 Jeremy Bowen, ‘Trump’s Middle East Peace Plan: “Deal of the Century” Is Huge Gamble’, BBC, 29 January 2020.

- 13 Anne Gearan and Souad Mekhennet, ‘Israel–UAE Deal Shows How the Very Notion of Middle East Peace Has Shifted Under Trump’, Washington Post, 16 August 2020.

- 14 See ‘Settlements Data’, Peace Now, 2021.

- 15 Ibid.

- 16 Josef Federman, ‘Israel OKs Hundreds of Settlement Homes in Last-Minute Push’, ABC News, 17 January 2021.

- 17 ‘Number of Palestinians Made Homeless by Israeli Demolitions Hits Four-year High Despite Pandemic’, Independent, 30 October 2020.

- 18 Gisha, ‘Human Rights Groups Demand Israeli Military End Incursions into Gaza’s Farmlands, Compensate Farmers for Damages’, 11 November 2020.

- 19 Ibid.

- 20 Tovah Lazaroff, ‘UN: Settler Violence Against Palestinians Has Increased During COVID-19’, Jerusalem Post, 4 April 2010.

- 21 Yaniv Kubovich, ‘Israeli Defense Officials Alarmed by Rise in Settler Violence Against Police, Soldiers’, Haaretz, 10 January 2021.

- 22 ‘Dozens of Palestinians Injured in West Bank Clashes With IDF: Report’, i24News, 11 October 2020.

- 23 United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, ‘UN Experts Alarmed by Sixth Palestinian Child Killing by Israeli Forces in 2020, Call for Accountability’, 17 December 2020.

- 24 B’Tselem, ‘Jan.–Feb. 2020: Military Blocks Five West Bank Villages as Collective Punishment’, 9 April 2020.

- 25 Omar Shakir, ‘Palestinian Authority Jails Journalist Again Over Facebook Post’, Human Rights Watch, 25 June 2020.

- 26 ‘Israel: Ensure Equal COVID-19 Vaccine Access to Palestinians – UN Independent Experts’, UN News, 14 January 2021.

- 27 Adam Rasgon, ‘Israel’s Vaccine Success Unleashes a Debate on Palestinian Inequities’, New York Times, 4 February 2021.

- 28 In early February the PA received 10,000 doses of the Russian vaccine; see ibid.

- 29 Fares Akram and Joseph Krauss, ‘After Delay, Israel Allows Vaccines into Hamas-run Gaza’, Washington Post, 17 February 2021.

- 30 ‘UN Report Finds Gaza Suffered $16.7 Billion Loss from Siege and Occupation’, UN News, 25 November 2020.

- 31 Gisha, ‘Gaza Unemployment Rate in the Second Quarter of 2020: 49.1%’,21 September 2020.

- 32 World Bank, ‘Palestinian Economy Struggles as Coronavirus Inflicts Losses’, 1 June 2020.

- 33 ‘Qatar Pledges $360 Million in Aid to Hamas-ruled Gaza’, Associated Press, 31 January 2021.

- 34 ‘Coronavirus “Feeds Off Instability”, Disrupting Israel–Palestine Peace Efforts’, UN News, 26 October 2020.

- 35 ‘Mahmoud Abbas Announces First Palestinian Elections in 15 Years’, Guardian, 15 January 2021.

- 36 Khaled Abu Toameh, ‘PA Arrests Hamas Supporters Ahead of Elections’, Jerusalem Post, 31 January 2021.

- 37 Hugh Lovatt, ‘The End of Oslo: A New European Strategy on Israel–Palestine’, European Council on Foreign Relations, 9 December 2020.

- 38 See ‘Israeli Public Opinion Polls: Regarding Peace With the Palestinians 1978–2020’, poll by Zogby Research Services, 4 December 2016.

Source: IISS; Yemen Ministry of Oil and Minerals; Energy Intelligence

Overview

The conflict in Yemen is the outcome of the contested evolution of the 2011 popular uprising against Ali Abdullah Saleh, as well as continued unaddressed grievances from Yemen’s post-1990 unification. Despite a power-sharing government and the efforts of the National Dialogue Conference to redraw the constitution and introduce a federal state between 2012 and 2014, conflict prevailed over compromise. The externally brokered transition in 2012 that replaced Saleh with Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi proved fraught and led to the gradual emergence of three political-military poles with competing external backing: a loose alliance supporting president Hadi, backed by Saudi Arabia and the Saudi-led coalition; the Houthi movement, also known as Ansarullah (‘Partisans of God’), which receives military support from Iran; and the secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC), informally supported by the United Arab Emirates (UAE).