5 Asia

Conflict Reports

Conflict Summaries

Overview

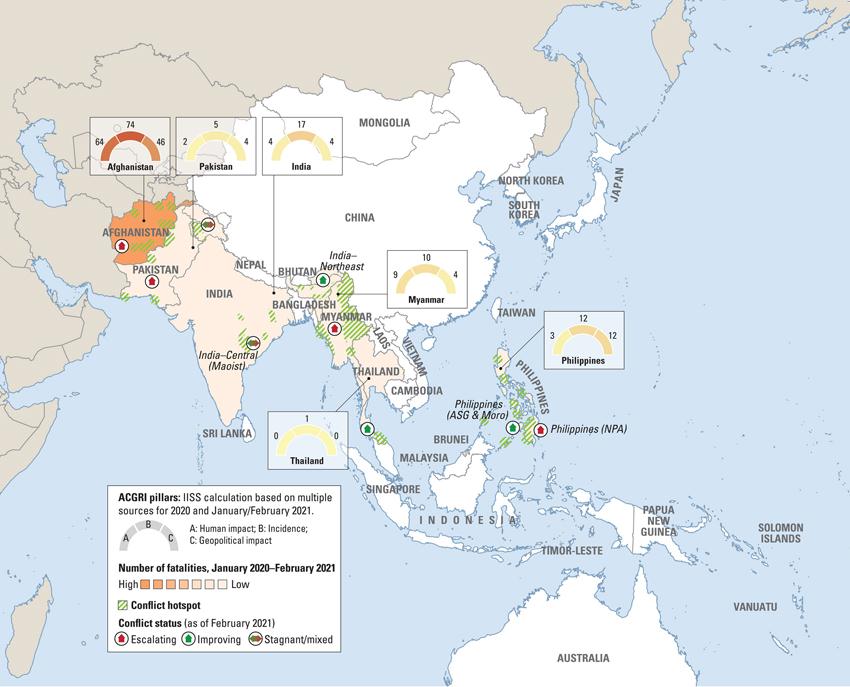

South and Southeast Asia play host to a number of long-standing armed conflicts. Three of them – the civil war in Afghanistan,1 Pakistan’s struggle with ethnic insurgency and anti-state terrorist groups, and the dispute over Kashmir – have a significant impact on both regional and global security, primarily due to the transnational actors involved and the potential of the Kashmir dispute to escalate into conventional war between nuclear powers India and Pakistan. The region’s other conflicts are more localised with a lower impact on regional dynamics. These are the struggle between Myanmar’s military and ethnic armed organisations (EAOs), which has also included severe persecution of ethnic minorities; the Malay Muslim ethno-nationalist autonomy movement and insurgency in Thailand; the Philippines’ two conflicts with the New People’s Army (NPA) and Moro rebels and Islamist terrorist groups; and India’s Maoist insurgency and conflict in the Northeast.

The United States’ 2001 invasion of Afghanistan marked the latest phase of a four-decade civil war that has involved many third parties. The conflict has significant international implications, especially as US and NATO forces withdraw from the country in mid-2021.2 Regional countries including China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Russia and also the US would prefer state stability rather than civil war; none favour a return to the Taliban’s former Islamic Emirate. However, the US, India and Pakistan have different priorities, as New Delhi and Islamabad compete for influence and play out their strategic rivalry, partly fuelled by the Kashmir dispute. While Pakistan would ultimately prefer a stable state, it would be deeply concerned by an Afghanistan closely aligned with India. Therefore, tensions between India and Pakistan, and the latter’s internal conflicts, affect each country’s calculations regarding Afghanistan, particularly vis-à-vis Pakistan’s support for the Taliban. These tensions risk prolonging the conflict.

The conflict along the Line of Control (LoC) demarcating Indian-administered and Pakistanadministered Kashmir saw raised levels of violence but lower than the highs of the mid- and late-1990s. New Delhi’s controversial decision in August 2019 to end the ‘semi-autonomous’ constitutional status of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir led to tensions with China, Nepal and Pakistan. There was also a significant uptick in the number of annual ceasefire violations across the LoC.

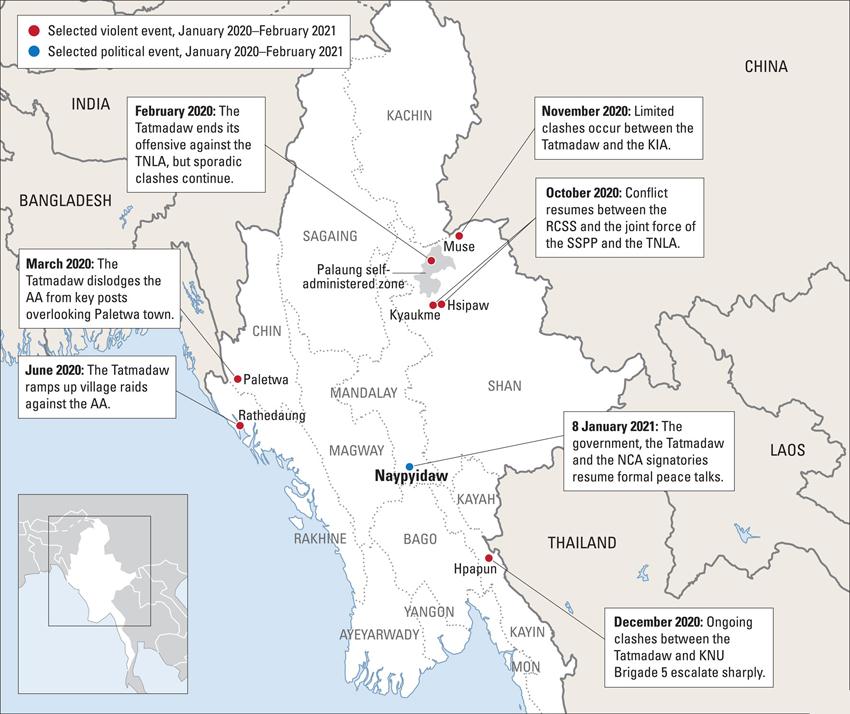

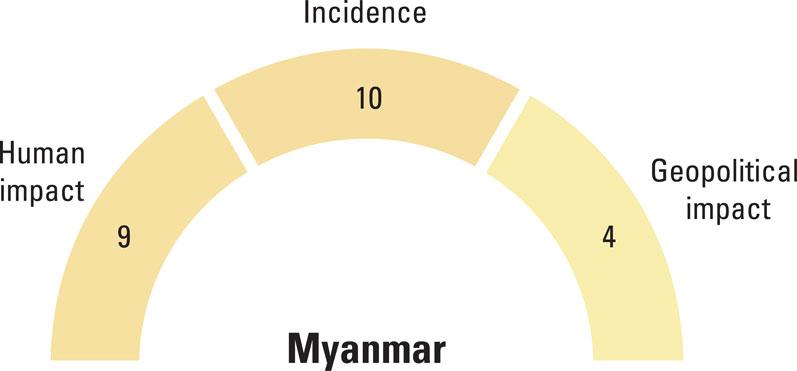

A coup by the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) in February 2021 received global attention. The armed forces seized power from the civilian government following a manufactured political crisis over the results of the November 2020 elections, which had produced a landslide win for the National League for Democracy (NLD) party. A massive popular uprising in Myanmar’s urban centres was quickly met with a bloody crackdown and mass arrests by the Tatmadaw. In response, the United Nations Security Council and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) called for a return to the status quo and an end to the violence. The US, United Kingdom and European Union imposed sanctions on Myanmar and suspended aid.

Regional Trends

Persistence of internal conflict

South and Southeast Asia’s conflicts are primarily internal, with the exception of Kashmir. The war in Afghanistan is an internal conflict that has become internationalised by notable thirdparty intervention. The Taliban remains backed by Pakistan, while Kabul relies heavily on US aid and has a close relationship with India. China, Iran and Russia have periodically supported both sides and vie for influence using political, security, economic and ethnic levers. Terrorist groups operating in the border areas between Pakistan and Afghanistan also affect and are affected by the war in Afghanistan and Pakistan’s own internal conflict. For example, the virulently anti-Pakistan Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) has taken refuge in Afghanistan and is escalating attacks inside Pakistan after reabsorbing splinter groups throughout 2020.

India’s conflict with CPI-Maoist is largely localised; so too are the Philippines’ conflicts with the NPA and Moro Muslim rebels, and the Malay Muslim ethno-nationalist insurgency in Thailand. The conflict in Myanmar is primarily internal but has resulted in approximately 855,000 Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.3 India’s conflict in the northeast is also affected by insecurity across the border, with Naga, Assamese and Manipuri armed groups utilising disrupted but still-intact sanctuaries in Myanmar.

The influence of transnational jihad

The rise of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) has impacted the conflicts in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as the Philippines’ fight against the Islamist Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG). The ISIS affiliate in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISIS–KP), primarily recruits former TTP members and claimed responsibility for some of the most brutal attacks against ethnic and religious minorities in the region in 2020. In the Philippines, ASG, Ansar Khalifah Philippines and Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters maintained their allegiance to ISIS. Notably, the ethnonationalist insurgency in southern Thailand has remained centred on regional identity and demands for an independent state, having resisted influence from transnational jihadist groups.

Peace processes make progress

In 2020, some gradual progress was made in peace processes in the Philippines, Thailand, and between India and Pakistan, but without any permanent settlements. Most positively, a joint statement by India’s and Pakistan’s Directors General of Military Operations agreed to a ceasefire along the LoC – the site of frequent artillery exchanges between the two countries. Dialogue stalled between the Communist Party of the Philippines and its armed wing (the NPA) on the one hand, and the strongman president of the Philippines Rodrigo Duterte on the other. In December 2020, Duterte declared that peace talks had been halted due to NPA attacks and forbade the agreement of local ceasefires. Elsewhere in the Philippines, a three-year extension of the transition period for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) was backed by the BARMM chief minister and Philippines government, allowing a relative peace to prevail between Manila and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front despite delays to the latter’s disarmament. In 2020, the Thailand National Security Council’s Peace Dialogue Panel met with the Patani Malay National Revolutionary Front (BRN) separatists in a formal setting for the first time. The BRN unilaterally ceased hostile activities to better enable the government’s response effort to the coronavirus pandemic.

Regional Drivers

Political and institutional

The most active conflicts in the region are rooted in the ethnic, religious, irredentist and centre–province tensions that emerged in newly formed post-colonial states. The 1909 Anglo-Siamese Treaty demarcated the border between what later became modern Thailand and Malaysia, splitting the historical Muslim sultanate of Patani and laying the groundwork for the Malay Muslim ethnonationalist autonomy movement that drives insurgency in southern Thailand. In 1947, the last Hindu ruler of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir opted to join the Indian Union rather than Pakistan, effectively splitting Kashmir between India and Pakistan and giving rise to the current conflict. Baloch insurgency and insecurity in Pakistan’s Pashtun tribal areas stem partly from questions over the Durand Line as the legitimate border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as a post-colonial order that split Pakistan into two wings – West Pakistan, which resembles today’s borders, and East Pakistan, which is majority Bengali – following partition. This post-colonial order, followed by the secession of East Pakistan to become Bangladesh, gradually led to ethnic resentment as the Punjab province came to dominate others. Myanmar’s independence from British rule in 1948 placed numerous ethnic minorities under the control of the Bamar majority, a circumstance which set in motion the current conflict.

Very often, this post-colonial legacy has combined with issues of identity, lack of political representation and the search for autonomy to drive many Asian conflicts, particularly in Kashmir, Pakistan (especially among Baloch separatists), India (the Communist Party of India–Maoist (CPI–Maoist)), Myanmar, the Philippines (ASG and Moro rebels) and Thailand. States have responded harshly to non-state actors’ efforts for greater autonomy with military measures and restrictions. These have often targeted civilian populations that have ethnic or religious affiliations to non-state actors, impacting citizens’ daily lives and thereby serving as an additional conflict driver. Myanmar’s multiple internal armed conflicts are largely driven by EAOs’ struggles for greater autonomy in remote borderlands, with efforts to demarcate territory by force ahead of peace negotiations leading to fighting between armed groups.

Central governments have tended to conflate demands for greater civil liberties and limited autonomy with violent separatist movements, as seen in Pakistan’s suppression of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which demands greater civil rights for Pashtuns and uses anti-state rhetoric but is distinguishable from violent groups like the TTP. Jammu and Kashmir’s integration with the Indian Union in August 2019 was a key driver of the Muslim-majority population’s intensified political resistance against New Delhi. Government measures to prevent violent protests – including curfews, internet shutdowns and the deployment of additional Indian paramilitary and army personnel – fuelled resentment, whereas the contrasting government approach in areas with CPI-Maoist presence, focusing on service provision, alleviated conflict drivers. Long-lasting insurgencies, such as the Afghan Taliban and the Philippines’ NPA, have also been enabled by their strong ideological unity and cohesion, and at times their decentralisation.

Economic and social

Socio-economic inequalities are root causes of the insurgencies in India, Pakistan and the Philippines. Poverty and lack of economic opportunities in parts of the Philippines continue to provide recruits for both Moro Muslim rebel groups and the NPA. India’s CPI-Maoist has long tapped into sentiments of disenfranchisement in impoverished rural populations. Similarly, the conflict between Pakistan and Baloch insurgents is partially fuelled by economic inequality, seen most recently in the distribution of economic benefits derived from natural-resource extraction and the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) traversing Balochistan. In Myanmar, Pakistan and the Philippines, insurgents have cited internal migration of majority ethnic and religious groups to minority areas, or the entry of multinational (especially Chinese) firms, as key motivators for continued fighting. Projects like CPEC and the China–Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) simultaneously motivate resistance and incentivise groups to consolidate control over future development zones so they can engage in rent seeking.

Illicit trade and informal taxation are also powerful economic drivers of conflict. The cultivation and export of illicit narcotics play a central role in Afghanistan, while illicit trade in narcotics, gems, timber and people fuels the conflict in Myanmar’s periphery. Civilian populations often find themselves caught between heavy-handed insurgencies and coercive state security forces; they are sometimes punished by both for perceived cooperation with the other.

Geopolitical

The conflicts in Afghanistan, disputed Kashmir, Pakistan and the Philippines have strong international drivers that often perpetuate violence by altering power dynamics on the ground. For example, the long-standing presence of US and NATO troops, regional support for the Taliban and other forms of covert and overt intervention in Afghanistan’s civil war are key drivers of conflict. The Taliban’s primary objective is the withdrawal of foreign forces followed by the overthrow of the government, which it views as an extension of foreign influence. The Taliban is enabled by a diverse group of foreign donors and sponsors that has at times included Iran, private Gulf donors and – most importantly – Pakistan. The Taliban also relies on safe havens in Pakistan and coordinates its operations through leadership councils in Quetta. Similarly, Islamabad often attributes terrorist violence in Pakistan to the safe havens found by militants in Afghanistan.

The spread of transnational jihadism in South and Southeast Asia – with various groups in the region pledging allegiance to ISIS since 2014 – also shapes the conflicts by radicalising populations and spawning new non-state actors that may derail ongoing negotiations between the original conflict parties.

Regional Outlook

Prospects for peace

Prospects for sustainable peace are slim in the short term, with some limited exceptions. In India’s Northeast, a final peace deal could be agreed with Naga armed groups in 2021–22. The largely observed ceasefire along the LoC may reduce violence in Kashmir, though further progress is needed for a political resolution of the conflict. India and Pakistan’s announcement of a renewed ceasefire along the LoC – initiated through ‘back channel’ talks – raised the prospects of a potential thaw in relations. If the back-channel talks progress successfully, they could lead to more normalised diplomatic relations, confidence-building measures and the resumption of official bilateral peace talks. However, it is too early to assess the opportunity this may present for a durable reduction in tensions.

The conflicts in Afghanistan, Kashmir, Myanmar and Pakistan have the greatest implications for continued regional and international insecurity. The withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan in 2021 marks an inflection point for outside intervention in the country and region. Kabul remains almost entirely reliant on outside assistance; continued aid from donor countries will likely require the government and Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF) to remain cohesive and intact. While the troop withdrawal will satisfy a key Taliban objective and justification for its activities, the development is unlikely to lessen the Taliban’s determination to seize additional territory by force, overrun military outposts and wear down the ANDSF. The Taliban is likely to continue limited peace talks to justify the operation of its diplomatic office in Qatar, while making demands for new prisoner releases and the removal of UN sanctions. However, it is unlikely to engage in substantive negotiations or the compromise necessary to reach a political settlement with the Afghan government without substantial pressure from the international community and its regional backers, including Pakistan.

The February 2021 coup made Myanmar’s peace process under the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement framework appear defunct. The Fourth Union Peace Conference of August 2020 was more symbolic than substantive; several notable signatories suspended their involvement. Though some EAOs may seek stability in their areas of operation by maintaining old ceasefires or upholding informal truces, these are now less likely to be honoured by either side.

Escalation potential and spillover risks

Attacks by Pakistan-based terrorist groups against Indian military targets in India-administered Kashmir in 2016 and 2019 led to brief conventional conflicts that included artillery exchanges, airstrikes and dogfights between fixed-wing aircraft. The unlikely but catastrophic potential for one of these episodes to spark a nuclear exchange is a perennial escalation risk.

In Afghanistan, violence levels are likely to spike after the US and NATO withdrawal as the Taliban seeks to gain territory, while ISIS–KP may attempt to remain relevant by staging large-scale terrorist attacks in urban centres. Afghanistan’s increased instability is likely to spill over into Pakistan, as the TTP and ISIS–KP become emboldened.

Myanmar could develop into a multi-front civil war in the borderlands and an armed resistance in urban areas. The Tatmadaw is likely to continue crackdowns in urban centres and attacks on civilian populations in rural areas inhabited by ethnic minorities. Large numbers of refugees are likely to enter Bangladesh but the conflict itself should remain contained, as should low-intensity conflicts including India’s CPI-Maoist insurgency and the separatist movements in southern Thailand and the Philippines.

Geopolitical changes

The role of external powers is likely to become more regionalised in the short term as the US and NATO withdraw from Afghanistan. Eurasian powers, including China, India and Russia, will likely be forced to play a larger role in supporting efforts to establish and maintain regional stability, including in Afghanistan and Myanmar. Chinese investment projects across the region, especially in Pakistan’s Balochistan province, will continue to encounter attacks from separatist groups and perhaps increasingly from terrorist groups. Despite their mediation efforts, regional and international powers are unlikely to play a major role in Kashmir. Although the coup in Myanmar was broadly condemned by the international community, Russia and China blocked the imposition of UN sanctions against the military government, meaning the country’s political and military conflicts have continued to play out in relative isolation.

The geographies of transnational militant groups are also changing: they are likely to increase their operations in South Asia following the withdrawal of US and NATO forces from Afghanistan, while reducing their presence in Southeast Asia, including in the Philippines, where the number of foreign terrorist fighters is ebbing.

Notes

- 1 The dramatic developments in the Afghanistan conflict in mid-2021, which culminated with the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August, are not covered in the Regional Analysis. See addendum to the Afghanistan chapter for a brief analysis of these developments.

- 2 NATO, ‘Nato and Afghanistan’, 9 June 2021.

- 3 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, ‘UN Appeals for US$877 Million for Rohingya Refugee Response in Bangladesh’, 3 March 2020.

Overview

The four-decade conflict in Afghanistan has experienced multiple phases, including the 1979–89 Soviet–Afghan War which was fought between the former Soviet Union and a group of Afghan militias collectively referred to as the mujahideen and the 1992–96 Afghan Civil War, in which the Taliban consolidated its hold on power in the country. The latest phase began with the United States’ invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, which followed the 9/11 terrorist attacks. At its outset the invasion set out to destroy the al-Qaeda terrorist organisation. However, the objective expanded to include the overthrow of the Taliban regime after its then-leader Mullah Omar refused to hand over the al-Qaeda founder, Osama bin Laden, to the US. In November 2001, using a combination of special forces and conventional units and a strategic partnership with the Northern Alliance (an anti-Taliban group formed in 1996), the US-led operation removed the Taliban regime from power. As a result, the Taliban’s structure and leadership quickly dissipated. In December 2001, the Bonn Conference set the groundwork for a new government of Afghanistan headed by Hamid Karzai and led to the creation of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) by the United Nations Security Council to train and assist the newly formed Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF).

The first three years after the invasion passed relatively smoothly and presidential elections on 9 October 2004 confirmed Karzai as president by a large margin. However, during this period, the low levels of US security presence – which made up the majority of ISAF – and the nascent ANDSF had left space for local strongmen and militia leaders – sometimes backed by US forces – to fill the power vacuum, and also allowed for the Taliban to reconstitute and reorganise in Pakistan. By 2005 Taliban fighters had begun conducting more significant operations in Afghanistan, with violence increasing every year up to 2010. In response, coalition forces began increasing troop numbers and expanding their presence throughout the country. By 2006, ISAF operated in all regions of Afghanistan. The US security personnel deployed in Afghanistan peaked with more than 100,000 in 2010–11 as part of then-president Barack Obama’s surge strategy before falling again to approximately 9,000 by the end of his term.1 The surge strategy inflicted high costs on the Taliban but a significant number of districts remained contested or fell as foreign troop numbers withdrew from more remote outposts.

ACGRI pillars: IISS calculation based on multiple sources for 2020 and January/February 2021 (scale: 0–100). See Notes on Methodology and Data Appendix for further details on Key Conflict Statistics.

In autumn 2018, then-US president Donald Trump appointed Zalmay Khalilzad as Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation. On 28 January 2019, Khalilzad announced that the Taliban and the US had agreed, in principle, to the framework of a deal, which was signed on 29 February 2020. The deal called for the release of up to 5,000 Taliban prisoners held by the Afghan government, the eventual removal of US and UN sanctions on the Taliban, and the gradual reduction of US forces stationed in the country leading to a full withdrawal by May 2021. In exchange, the Taliban agreed to release 1,000 Afghan prisoners, participate in negotiations with the Afghan government and provide counter-terrorism assurances. However, contested election results and a dispute over prisoner releases delayed the start of intra-Afghan negotiations from March until September 2020. As of February 2021 these remained ongoing without reaching a political settlement. The Taliban maintained high levels of violence until the end of 2020.

Conflict Parties

Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF)

Strength: 270,400, including 178,800 under the Afghan National Army and the Afghan Air Force, and 91,600 paramilitary and Afghan National Police.

Areas of operation: Operates in all 34 provinces but with more limited freedom of movement in areas controlled or contested by the Taliban. The government controls 133 districts, where 85.9% of the population lives, and the Taliban contests 187 and controls 75 (mostly rural) districts.2

Leadership: President Ashraf Ghani (commander-inchief), Asadullah Khalid (minister of defence) and General Mohammad Yasin Zia (chief of general staff).

Structure: Organised under the minister of defence and the chief of general staff with five regional commands (or corps) – the 201st in Kabul, the 203rd in Gardez, the 205th in Kandahar, the 207th in Herat and the 209th in Mazar-e-Sharif. Separate commands exist for the Kabul military training centre, the military academy and the general staff college.

History: Established in 2002 following the collapse of the Taliban regime. Slow initial growth with only 27,000 troops by 2005, but increased after the Taliban resurgence. New commandos began training and entered service in 2007. Took full responsibility for security in Afghanistan in 2015 after the official end of combat operations by coalition forces in 2014. In practice, the ANDSF is still highly dependent on foreign aid, training, and direct and indirect operational support.

Objectives: (Aspires to) control all districts within Afghanistan without any challenge from non-state actors.

Opponents: The Taliban, Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISIS–KP) and other anti-government forces.

Affiliates/allies: Relies on US support through the Bilateral Security Agreement of 2014. The US continues to pay salaries for the security forces.

Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF)

Resources/capabilities: The US spent an estimated US$4.2 billion directly on Afghan security forces in 2020 and requested US$4bn for 2021.3 The ANDSF has 174 aircraft (including fixed-wing platforms and helicopters), artillery, mortars, armoured vehicles and drones. However, it lacks the human resources needed to maintain and operate its aircraft and is therefore reliant upon support from foreign advisers.4

The Taliban

Strength: 60,000 core fighters (estimate).5

Areas of operation: Maintains ‘shadow governments’ in the districts it controls throughout the country and has named shadow provincial governors in all 34 provinces. As of January 2021, the group continued to carry out large-scale attacks in major cities and controlled an estimated 75 districts while contesting a further 187 districts.

Leadership: Led by Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada. Together with deputies Sirajuddin Haqqani (leader of the Haqqani network) and Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob (son of Taliban founder Mullah Mohammad Omar), he heads the Quetta Shura, which directs the military campaign against the Afghan government and coalition forces.

Structure: Formally, the Taliban consists of the leader and deputy leaders, executive offices, a shura (leadership council) and 12 commissions covering military affairs, political affairs, economic affairs, education, prisoners, martyrs and disabled members, as well as the Council of Ulema (Council of Senior Religious Scholars). The organisation is historically polycentric, but power is increasingly concentrated in the Quetta Shura and among the top leaders.

History: The Taliban (translated as ‘the students’) movement began in the Afghan refugee camps of Pakistan following the 1979 Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan. Under Mullah Omar, the group entered the Afghan Civil War in 1994 with the capture of Kandahar city. Taliban fighters quickly conquered other areas of Afghanistan and it officially ruled as an Islamic emirate from 1996 to 2001, though it never controlled the whole country.

Objectives: Since the US invasion in 2001, its main goal is the expulsion of foreign troops, the overthrow of the Kabul government (considered a foreign puppet), the dissolution of the 2004 Afghan constitution and a return to a strict Islamic government modelled on an emirate.

Opponents: US and NATO-led forces, the Afghan government and ISIS–KP.

Affiliates/allies: Connections of varying formalities with a variety of other non-state armed groups in South Asia, including al-Qaeda, the Haqqani network, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).

Resources/capabilities: Estimates of the Taliban’s annual revenue range from US$300 million to US$1.6bn.6 Much of this revenue comes from the group’s involvement in the drug trade, extortion practices or from taxes collected in the territory it controls. However, projected figures for the group’s revenue vary, especially that which is gained from the drug trade.7 Interviews with current and former fighters have shown that donations from Persian Gulf charities and wealthy individuals have increased significantly in recent years.8 The Taliban has local and expeditionary units that use small arms, mortars, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), vehicle-borne IEDs (VBIEDs) and unencrypted communications equipment. It also benefits from equipment lost or sold by, or stolen from, the ANDSF, including night-vision goggles, armoured vehicles and weapons optics.

Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISIS–KP)

Strength: 2,500–4,000 (estimate).9

Areas of operation: Primarily confined to a small region of Nangarhar province in eastern Afghanistan but has also had small presences in Helmand, Jowzjan, Kunar and Zabul provinces.

Leadership: Led by Shahab al-Muhajir. The original leader, Hafiz Saeed Khan (previously head of the TTP Orakzai faction), was killed in a US drone strike in July 2016. Successive leaders were also either killed in US strikes or arrested.10

Structure: An Islamist militant organisation, formally affiliated with the larger Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, of which it is the Central and South Asia branch.

History: Formed and pledged loyalty to then-ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in October 2014. The initial membership primarily comprised disgruntled and estranged members of the TTP.

Objectives: Similar to ISIS, ISIS–KP maintains both local and global ambitions to establish a caliphate in Central and South Asia to be governed under a strict Islamic system, modelled after the group’s own interpretation of a caliphate.

Opponents: Mainly focuses on fighting the government in Kabul and international forces in Afghanistan, but also frequently clashes with the Taliban and Pakistani security forces.

Affiliates/allies: ISIS.

Resources/capabilities: Since its founding in 2014, ISIS has invested in improving ISIS–KP’s organisation and capabilities. However, with the decline of its territory in Iraq and Syria, ISIS has fewer resources to invest in foreign networks and therefore its investment in ISIS–KP has declined. ISIS–KP relies on small arms, IEDs and VBIEDs.

Al-Qaeda

Strength: 400–600 fighters in Afghanistan.11

Areas of operation: The mountainous region between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Leadership: Led by Ayman al-Zawahiri since 2011.

Structure: Below Zawahiri and his immediate advisers, maintains a shura council and committees for communications, finance and military operations.

History: Created as a broad alliance structure by Arab fighters who travelled to Afghanistan and Pakistan to fight against the Soviet invasion in the 1980s. The organisation (officially formed in 1988) was initially led by Osama bin Laden, who envisioned it as a base for a global jihadist movement to train operatives and to support other jihadist organisations throughout the world. The group was responsible for a number of high-profile terrorist attacks against the US, including the 9/11 attacks. Bin Laden was killed in a US special-operations raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan, in 2011.

Objectives: Focus has always been to fight the ‘far enemy’ (the West) and particularly the US, which supports current Middle Eastern regimes, and bring about Islamist governance in the Muslim world. Its affiliate groups often pursue local objectives independent of the goals and strategy of the central organisation.

Opponents: US and other Western countries supporting non-Islamic regimes.

Affiliates/allies: Currently maintains an affiliation with five groups: al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in North Africa, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in Yemen, al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) in South Asia, Jabhat Al-Nusra in Syria and al-Shabaab in Somalia. As of 2020, it still maintains a strong relationship with the Taliban.12

Resources/capabilities: Capable of engaging in complex terrorist attacks on hard and soft targets. It has also provided military advice to the Afghan Taliban.

Resolute Support Mission (RSM), including Operation Freedom's Sentinel. Formerly International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and Operation Enduring Freedom

Strength: NATO countries and partners contribute 9,592 personnel to the Resolute Support Mission (RSM), including 2,500 US troops as part of Operation Freedom’s Sentinel. After the US, the four countries contributing the most troops are Germany (1,300), Italy (895), Georgia (860) and the United Kingdom (750).13

Areas of operation: Operation Freedom’s Sentinel conducts counter-terrorism missions throughout the country and the RSM maintains a central command in Kabul, with supporting commands in Mazar-e-Sharif, Herat, Kandahar and Laghman.

Leadership: General Austin Scott Miller (commander of both US forces and the NATO mission in Afghanistan since September 2018).

Structure: Coalition forces in Afghanistan are divided into two missions: US forces focusing on counter-terrorism under Operation Freedom’s Sentinel and NATO forces focusing on training and advising under the RSM.

History: Coalition forces entered Afghanistan in 2001 and ISAF was created in accordance with the 2001 Bonn Conference. With the official conclusion of offensive combat operations by foreign forces in 2014, ISAF became the RSM and US forces transitioned from Operation Enduring Freedom to Operation Freedom’s Sentinel.

Objectives: Continue supporting the government in Kabul in the country’s democratisation and development. Prevent the rise of transnational terrorist organisations that might use Afghanistan as a base to plan and coordinate international attacks.

Opponents: The Taliban insurgency (although the ANDSF are the primary actors engaging the Taliban) and terrorist groups including al-Qaeda and ISIS–KP

Affiliates/allies: 36 countries participate in various missions in Afghanistan through the RSM. The UN also maintains a mission in the country to promote peace and stability, the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA).

Resources/capabilities: The US has spent nearly US$2 trillion on the conflict in Afghanistan. The estimated annual budget for all US operations, including reconstruction efforts, is approximately US$50bn. The NATO-led mission has sophisticated aircraft, artillery, mortars, High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS), surveillance drones, armoured vehicles and advanced communications technology.

Conflict Drivers

Political

Democratic legitimacy and governance flaws:

Weak governance and widespread corruption continue to plague Afghanistan. The 2014 presidential election required US-led and UN-backed mediation to resolve the contested results. The 2019 election was also contested and required closed-door negotiation to reach a political settlement, which in turn delayed the beginning of intra-Afghan peace negotiations.

Between May 2009 and 31 December 2019, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction found US$19bn in waste, fraud and abuse.14 95% of respondents to the 2020 Asia Foundation survey stated that corruption was a major problem in Afghanistan.15 Faith in institutions is also lacking, with only 53.9% of Afghans believing that the Afghan National Police improves security in the country, although this represents a notable increase from 36.4% in 2019.16

Economic and social

Ideological and subnational divisions:

Ideological and ethnic divisions are a major driver of violence and have fuelled conflict in Afghanistan over the past 43 years. The country has at least 14 ethnic groups and is divided along urban–rural and sectarian lines. The ethnic dimension of the conflict stems from the fact that the Afghan government comprises stakeholders from multiple ethnic groups, including Pashtuns, while the Taliban is a Pashtun-dominated insurgency, although it does have members from other groups. While the ethnic component of the conflict should not be exaggerated, ethnic polarisation is indeed a major obstacle to consensus building that inhibits the agreement of a political settlement. Loyalty to ethnicity and patronage networks often rivals national identity and polarisation is further fuelled by the perception that foreign aid is both misallocated and distributed unequally across regions and social classes. Low economic development, which leads to aid dependency, also fuels corruption.

Liberal democracy, civic liberties and women’s rights were difficult to reconcile with the Islamist form of governance pursued by the Taliban in the 1990s and which it is seeking to restore. Opportunities for upward economic mobility are rare in Afghanistan, especially for women, as shown by the country’s rank (169th out of 189) in the UN Development Programme’s Gender Inequality Index.17

International

Third parties’ involvement:

The continued presence of coalition troops, regional support for the Taliban and other forms of covert and overt intervention in Afghan domestic affairs are key drivers of the conflict. The Taliban’s primary goal remains the withdrawal of all foreign troops followed by the overthrow of the Afghan government. The Taliban is enabled by a diverse group of foreign donors and sponsors which have included China, private Gulf donors, at times Iran, and most importantly Pakistan. The Taliban also relies on safe havens in Pakistan and coordinates its operations through leadership councils in Quetta. Pakistan’s primary interest in supporting the Taliban is to prevent Afghanistan from aligning with India. While Iran and the Taliban were historic enemies, the former’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps has periodically provided financial support and training to the latter to encourage their opposition to and harassment of US troops.

Without external funding, the Taliban’s fighting capacity would be significantly diminished. The ANDSF funding model also relies completely on foreign aid, almost entirely from the US, and its combat capabilities depend largely on direct and indirect US operational support. One analysis concluded that if US troops were to leave Afghanistan, ‘the Taliban would enjoy a slight military advantage that would increase in a compounding manner over time.’18

Political and Military Developments

The US–Taliban agreement

On 29 February 2020, the Taliban and the US signed the Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan (‘US–Taliban agreement’).19 This agreement called for the release of up to 5,000 Taliban prisoners by the Afghan government, the eventual removal of US and UN sanctions on the Taliban, and the gradual reduction of US forces towards a full withdrawal by May 2021. In exchange, the Taliban agreed to participate in intra-Afghan negotiations with the Afghan government, work towards a ceasefire and a political settlement, and prevent any group (including al-Qaeda) from using Afghan soil to threaten the security of the US and its allies.

Challenging intra-Afghan negotiations

Intra-Afghan negotiations did not begin in March 2020, as originally outlined by the US–Taliban agreement, due to delays in prisoner releases and a dispute between President Ghani and his political rival Abdullah Abdullah over the 2019 election results. The Trump administration threatened to withhold US$1bn in aid to the Afghan government, which prompted some compromise between the two politicians.20 Intra-Afghan negotiations finally began on 12 September 2020 but were marred by a Taliban offensive on the outer areas of the capital of Helmand province, Lashkar Gah. The two sides did not reach an agreement on rules and procedures for negotiating substantive questions until 2 December 2020. Shortly after this breakthrough, the Afghan government and the Taliban announced a 22-day recess from negotiations. Negotiations briefly resumed in January 2021 and then abruptly ended as Taliban leaders visited foreign countries, including Iran and Russia, to bolster regional support. Talks resumed once again in late February 2021.

Continued Taliban violence

The dynamics of the conflict in Afghanistan changed significantly once the Taliban and the Afghan government initiated intra-Afghan negotiations. Nevertheless, the Taliban continued to maintain high levels of violent activity, seeing it as its primary source of leverage over the US and the Afghan government. The Afghanistan National Security Council reported that the Taliban conducted 2,804 attacks between 1 March and 19 April 2020, which it claimed violated the US–Taliban agreement.21 Ghani views a ceasefire as a necessary precondition to peace talks, but this has been rejected by the Taliban. However, the US–Taliban agreement significantly lowered the levels of violence faced by coalition troops. Four US combat deaths occurred in January and early February of 2020 and as of 8 February 2021, the US had gone a full year without suffering a single combat death in Afghanistan.22 This reduction in US fatalities was the combined result of both the US–Taliban agreement and the decline in US operational tempo. Other NATO troops also benefited from the reduction in violence aimed at foreign troops but were already largely disengaged from active combat operations prior to the US–Taliban agreement. ISIS–KP faced considerable pressure from both the Taliban and US and Afghan government forces in 2020, resulting in a significant decrease in its territory. However, the organisation still remained capable of carrying out attacks against US and Afghan forces.

Key Events in 2020–21

POLITICAL EVENTS

29 February 2020

The US and the Taliban sign the Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan.

9 March

Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah both take the oath of presidential office following a dispute over the 2019 election results.

17 May

Ghani and Abdullah sign a power-sharing agreement to end the election dispute. Ghani remains president.

26 May

The Afghan government releases 900 Taliban prisoners.

3 September

ISIS–KP attacks a prison in Jalalabad and kills 29 people.

24 November

Donor countries pledge US$12bn in aid to Afghanistan for the period 2021–24, with at least US$3.3bn to be distributed in the first year.

2 December

The Afghan government and the Taliban reach agreement on procedures to discuss substantive issues during intra-Afghan negotiations. The Taliban announces a 22-day recess shortly after.

5 January 2021

Negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan government resume but quickly lose momentum.

26–28 January

Taliban delegations travel to Iran and Russia to seek regional support for their negotiating positions.

MILITARY/VIOLENT EVENTS

8 February 2020

Last two US service members killed in combat prior to the signing of the US–Taliban agreement.

22 February

Ahead of the signing of the US–Taliban agreement, a sevenday ‘reduction in violence’ begins.

22–28 March

Taliban attacks ANDSF positions in Zabul province, killing 37, and initiates assaults in Kunduz, Faryab and Badakhshan.

25 April

The Afghanistan National Security Council reports that the Taliban conducted 2,804 attacks between 1 March and 19 April.

12 May

An unclaimed attack on a Kabul maternity ward kills 24 people.

18 June

The US reports a reduction in its troop levels to 8,600, in compliance with the US–Taliban agreement.

14 July

The Pentagon announces that US forces have withdrawn from five of their bases in Afghanistan to comply with the US–Taliban agreement.

31 July

The Taliban and ANDSF begin a three-day ceasefire for Eid al-Adha.

2–3 August

In an unsuccessful assassination attempt, Afghan First Vice-President Amrullah Saleh’s convoy is targeted with a roadside-bomb attack that leaves ten dead.

9 September

The Afghan government agrees to release 5,000 Taliban prisoners to begin intra-Afghan negotiations.

10 September

US secretary of defense Mark Esper announces that US troop levels in Afghanistan will fall below 5,000 by the end of November.

12 October

The Taliban launches an offensive on the provincial capital of Helmand province, Lashkar Gah.

24 October

ISIS–KP kills 24 people in Kabul in a suicide-bomb attack.

2 November

ISIS–KP storms Kabul University and kills 22 people.

17 November

US acting secretary of defense Christopher Miller announces that US troop levels in Afghanistan will decrease to 2,500.

December

The Taliban attacks checkpoints in districts surrounding Kandahar city.

15 January 2021

US Department of Defense announces that US troop levels have dropped to 2,500.

Impact

Human rights and humanitarian

While UNAMA reported a 15% decrease in civilian casualties in 2020 compared to 2019 and the total fell below 10,000 for the first time since 2013, the 3,035 Afghans killed and 5,785 injured over the year was still significant. There was an uptick in civilian casualties between October and December 2020 compared to the rest of the year, caused, in part, by the breakdown in intra-Afghan negotiations and by high rates of Taliban-led violence and unclaimed terrorist attacks. Civilian casualties during this threemonth period increased by 45% compared to the same period in 2019.23 Targeted killings of Afghan journalists, academics and activists increased in 2020, as did the opacity of the conflict since many of these attacks went unclaimed. Conflict-induced displacements decreased in 2020, with 404,139 internally displaced persons (IDPs) recorded by the UN compared to 460,603 in 2019,24 which is consistent with the slight reduction in overall violence inflicted on civilians. In contrast, 2021 is on track to be one of the deadliest years in the history of the war.

Political stability

The Afghan government’s hold remained relatively stable in the areas under its control, including Kabul and the majority of provincial capitals in 2020, despite patterns of violence targeting members of Afghan civil society and government figures. Such incidents included an assassination attempt on First Vice-President Amrullah Saleh in September 2020, and the targeted killing of Yousuf Rashid, who headed the Free and Fair Election Foundation of Afghanistan, in December 2020. As of February 2021, uncertainty over the potential withdrawal of US troops, rising levels of violence and the targeting of officials had fuelled public debate over the longterm viability of the Afghan government, though the immediate stability held firm.

Economic and social

Afghanistan entered the coronavirus pandemic with an already floundering economy. The IMF estimated that Afghanistan’s real GDP shrank by 5% in 2020, but it is predicted to recover by 4% in 2021.25 As a result of the pandemic, tax revenue from the sales of goods declined and cross-border trade was disrupted, especially with Pakistan. Afghanistan remained dependent on foreign assistance and at a Geneva meeting in November 2020, a number of international donor countries pledged a combined US$12bn in aid to the country over a period of four years, but with strict governance conditions attached.26

Relations with neighbouring and international partners and geopolitical implications

Intra-Afghan negotiations and the announcement that the US intends to withdraw all remaining troops from Afghanistan were by far the most impactful developments of the conflict in 2020 and early 2021. As October 2020 marked the 19-year anniversary of the US involvement in Afghanistan, the Trump administration prioritised efforts to withdraw US troops from the country, making its partnership with the Afghan government and the ANDSF increasingly tense. In March 2020, the Trump administration threatened to withhold US$1bn in aid to the Afghan government to break the stalemate between President Ghani and his political rival Abdullah Abdullah that was obstructing the intra-Afghan negotiations aimed at ending the war. Following Joe Biden’s election in November 2020, the Taliban leadership engaged in diplomatic outreach to gain regional support from its allies both for its continued use of violence during negotiations with the Afghan government and for its aim to initiate new military operations against NATO troops should they remain in Afghanistan beyond the May 2021 withdrawal deadline. In December 2020, a Taliban delegation visited Islamabad to meet with Prime Minister Imran Khan and later with Pakistan’s foreign minister, Shah Mahmood Qureshi, who expressed implicit support for the Taliban’s position that successful negotiations must precede a ceasefire. A Taliban delegation also travelled to Iran and Russia in early 2021, and Russian Special Envoy for Afghanistan Zamir Kabulov publicly supported the Taliban’s position that the US should adhere to the May withdrawal deadline.

Conflict Outlook

Political scenarios

The US remains the most consequential foreign actor affecting Afghanistan’s short-term trajectory, given its position as the primary source of ANDSF military support and given the Taliban’s explicit objective for their troop withdrawal. In April 2021, the Biden administration announced its intention to withdraw the remainder of US troops from Afghanistan by no later than 11 September 2021.

This date will keep US and NATO troops in Afghanistan beyond the May 2021 withdrawal deadline included in the US–Taliban agreement. However, so long as the Taliban determines a level of active engagement by the US and NATO in troop withdrawal, the trend of low US combat deaths will likely continue. While violence between the Taliban and foreign troops is likely to remain low, clashes between the Taliban and the ANDSF, as well as incidents of targeted killings and terrorism, are likely to remain high and even increase, particularly during the warm spring and summer months. The Taliban will attempt to consolidate territorial gains. Without the presence of foreign troops also fighting the Taliban, the latter will have little incentive to participate meaningfully in negotiations with the Afghan government since it calculates that it has the military advantage. In the absence of a negotiated political settlement, the Taliban would likely gradually capture provincial capitals and may eventually gain control of Kabul. In this scenario, the US and other international actors would likely attempt to use airstrikes, international aid, sanctions relief and global recognition as leverage to induce the Taliban to return to the negotiating table with the Afghan government. The success of such a strategy would depend on how much value the Taliban assigns to establishing its own international legitimacy and the continued cohesion of the Afghan government.

The Taliban’s targeting of ANDSF, Afghan government officials, journalists, academics, civil society and especially women in public roles is likely to continue. The Taliban is also very likely to conduct assaults on provincial capitals. The success of ANDSF attempts to repel these Taliban attacks and to regain control over urban centres already held or subsequently captured by the Taliban will likely depend on the availability of continued foreign air support and cohesion within ANDSF units. If NATO troops were still present in Afghanistan at this point, calls for increased deployment could arise. However, Washington would likely continue back-channel diplomacy with the Taliban during this period in order to restart negotiations toward a political settlement.

Whether or not foreign troops remain in the country, a negotiated political settlement to end the conflict in Afghanistan seems unlikely. The US–Taliban agreement was not fully implemented because both the Taliban as a party to the agreement, and the Afghan government as a reluctant beneficiary, applied a maximalist interpretation in their own favour. For example, the Taliban interpreted the clause calling for the release of ‘up to five thousand (5,000) prisoners’ to mean no less than 5,000. While not a party to the agreement, the Afghan government also applied a broad interpretation of its obligations to the Taliban, which obstructed the subsequent intra-Afghan negotiations. Notably, the US–Taliban agreement did not explicitly condition the US troop withdrawal on the successful completion of a political settlement between the Taliban and the Afghan government.

Escalation potential and conflict-related risks

A collapse of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in the short term is improbable. However, levels of violence are likely to rise regardless of developments with the peace negotiations. The most likely near-term outcome, leaving aside the US troop withdrawal, is an escalation in clashes between the Taliban and the ANDSF outside major urban centres, combined with targeted killings and terrorism inside Afghanistan’s cities.

Prospects for peace

Prospects for peace in 2021 are limited. The Taliban’s vision of governance and for a new constitution for Afghanistan, based on its version of Islam, is incompatible with the liberal-democratic model of an Islamic republic embraced by the post-Bonn political order.27 Those who have benefited from the established system will not want to alter it or to relinquish power to the Taliban, as already evidenced by Ghani’s resistance to the proposal of an interim government. Some actors within the Afghan government view the inclusion of the Taliban in the country’s political system as an existential threat. Meanwhile, the Taliban is unlikely to accept a power-sharing agreement with the sitting Afghan government especially given its military advantage over the ANDSF.

Strategic implications and global influences

Regional powers, Afghanistan’s immediate neighbours and factions within Afghanistan have all expressed support for a political settlement to end the conflict. However, there is little consensus over how to successfully negotiate such a settlement and what the acceptable terms of a peace deal and the model for a future government might be. The failure of the intra-Afghan negotiations to reach a compromise on substantive issues and the Taliban’s ongoing high levels of violence diminish the chances of reaching a durable negotiated settlement that could be successfully implemented. The lack of a willing and neutral third party to monitor and enforce a potential negotiated settlement also lowers any chance of long-term durability. An increasingly unstable Afghanistan that descends into civil war could attract regional actors to back local proxies, thus plunging the country deeper into conflict.

Afghanistan Conflict Report – August 2021 Addendum

Several deeply significant events took place in Afghanistan in July and August 2021, including the withdrawal of most foreign troops, the collapse of the Afghan government and Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF), and the expansion of Taliban territorial control across most of Afghanistan, including Kabul.

The Taliban made rapid gains throughout July in northern Afghanistan, taking dozens of districts.28 Some poorly supplied ANDSF outposts fell with little to no resistance and elite units became increasingly overstretched.29 The Taliban engaged in information operations to demoralise the ANDSF rank and file, spreading images of surrendering units.30 It also used local elders and powerbrokers to facilitate surrenders. On 25 June, President Ashraf Ghani met with US President Joe Biden in the White House to secure continued American support for his administration and to convince Biden to partially reverse his decision to withdraw all US troops by 31 August.31 The Biden administration remained steadfast in its commitment to withdraw troops but did provide some air support to the ANDSF in July.

In August, the Taliban rapidly seized border posts and provincial capitals, eventually capturing major cities such as Herat. On 15 August, the Taliban entered Kabul without a fight and Ghani and other senior Afghan officials fled. Prominent militia leaders Ata Noor and Abdul Rashid Dostum also fled the country following fighting in the north.32 A potential meeting between remaining Afghan leaders and the Taliban to establish an interim government never occurred and the Taliban declared an Emirate. As of late August, the US has deployed approximately 6,000 troops to Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport (along with troops from other NATO members) to facilitate the mass evacuation of remaining US citizens, former interpreters and Afghans admitted on humanitarian grounds.

Although the withdrawal of foreign troops and rapid increase in the Taliban’s territorial control suggest overall violence levels will decrease in Afghanistan, pockets of anti-Taliban resistance may still occur, especially in the Panjshir Valley. Incidents of targeted killings and violence against civilians by the Taliban will also likely continue, as will terrorist attacks by groups such as the Islamic State in Khorasan Province. Risks to regional and international stability also loom.

The latest developments will be covered in depth in The Armed Conflict Survey 2022, which will have a reporting period of March 2021-March 2022.

Notes

- 1 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, ‘Quarterly Report to the United States Congress’, 30 April 2018, Figure 3.32, p. 90.

- 2 Bill Roggio, ‘Mapping Taliban Control in Afghanistan’, FDD’s Long War Journal.

- 3 United States Department of Defense, ‘Defense Budget Overview: United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Request’, 13 May 2020, p. 64.

- 4 Jonathan Schroden, ‘Afghanistan’s Security Forces Versus the Taliban: A Net Assessment’, CTC Sentinel, vol. 14, no. 1, January 2021, pp. 20–9.

- 5 Ibid.

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 David Mansfield, ‘Understanding Control and Influence: What Opium Poppy and Tax Reveal About the Writ of the Afghan State’, Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, August 2017.

- 8 Antonio Giustozzi, The Taliban at War, 2001–2018 (London: Hurst, 2019).

- 9 United Nations Security Council, ‘Twenty-fourth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2368 (2017) Concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities’, S/2019/570, 15 July 2019, p. 15.

- 10 Andrew Mines and Amira Jadoon, ‘Can the Islamic State’s Afghan Province Survive Its Leadership Losses?’, Lawfare, 17 May 2020. See also Amira Jadoon and Andrew Mines, ‘Broken, but Not Defeated: An Examination of State-led Operations Against Islamic State Khorasan in Afghanistan and Pakistan (2015–2018)’, Combating Terrorism Center, March 2020.

- 11 United Nations Security Council, ‘Twenty-sixth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2368 (2017) Concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities’, S/2020/717, 23 July 2020, p. 15.

- 12 Asfandyar Mir, ‘Afghanistan’s Terrorism Challenge: The Political Trajectories of Al-Qaeda, the Afghan Taliban, and the Islamic State’, Middle East Institute Policy Paper, October 2020.

- 13 North Atlantic Treaty Organization, ‘Resolute Support Mission (RSM): Key Facts and Figures’, February 2021.

- 14 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, ‘Quarterly Report to the United States Congress’, 30 October 2020, p. 25.

- 15 The Asia Foundation, ‘Afghanistan Flash Surveys on Perceptions of Peace, COVID-19, and the Economy: Wave 1 Findings’, 23 November 2020, p. 71.

- 16 Ibid., p. 37.

- 17 United Nations Development Programme, ‘Human Development Report 2020’, 15 December 2020, p. 363.

- 18 Schroden, ‘Afghanistan’s Security Forces Versus the Taliban: A Net Assessment’, p. 27.

- 19 US Department of State, ‘Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan Between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan Which Is Not Recognized by the United States as a State and Is Known as the Taliban and the United States of America’, 29 February 2020.

- 20 Pamela Constable and John Hudson, ‘U.S. Vows to Cut $1 Billion in Aid to Afghanistan as Political Crisis Threatens Peace Deal’, Washington Post, 23 March 2020.

- 21 Khaled Nikzad, ‘Taliban Initiated 2,804 Attacks Post-peace Deal: Official’, Tolo News, 25 April 2020.

- 22 Phillip Walter Wellman, ‘US Goes One Year Without a Combat Death in Afghanistan as Taliban Warn Against Reneging on Peace Deal’, Stars and Stripes, 8 February 2021.

- 23 United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, ‘Afghanistan Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict: Annual Report 2020’, February 2021, p. 11–12.

- 24 United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Afghanistan – Conflict Induced Displacements in 2020’, March 2021; and United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Afghanistan – Conflict Induced Displacements in 2019’, March 2020.

- 25 International Monetary Fund, ‘World Economic Outlook Database’, April 2021.

- 26 ‘Foreign Aid to Afghanistan Could Reach $12 Billion Over Four Years, Some with Conditions’, Reuters, 24 November 2020.

- 27 This consisted of developments which followed the 2001 Bonn Conference, including the establishment of the transitional government, the elevation of certain political elites, the new 2004 Afghanistan constitution and the 2004 presidential elections.

- 28 Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Najim Rahim, ‘Taliban Enter Key Cities in Afghanistan’s North After Swift Offensive’, New York Times, 6 August 2021; and Susannah George, ‘Taliban’s Rapid Advance Across Afghanistan Puts Key Cities at Risk of Being Overtaken’, Washington Post, 7 July 2021.

- 29 Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Najim Rahim, ‘Elite Afghan Forces Suffer Horrific Casualties as Taliban Advance’, New York Times, 7 July 2021.

- 30 Benjamin Jenson, ‘How the Taliban Did It: Inside the “Operational Art” of Its Military Victory’, Atlantic Council, 15 August 2021.

- 31 US, White House, ‘Statement by White House Spokesperson Jen Psaki on the Visit of President Ashraf Ghani of Afghanistan and Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, Chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation’, 20 June 2021; and White House, ‘Remarks by President Biden on the Drawdown of U.S. Forces in Afghanistan’, 8 July 2021.

- 32 ‘Afghan Militia Leaders Atta Noor, Dostum Escape “Conspiracy”’, Reuters, 14 August 2021; and Ata Mohammad Noor (@Atamohammadnoor), tweet, 14 August 2021.

Overview

Since its formation in 1947, Pakistan has struggled with ethnic and centre-province tensions stemming from the perceived marginalisation of the Baloch, Pashtuns and Sindhis by the Punjabi majority. The secession of East Pakistan to form Bangladesh in 1971 enhanced this dynamic, as it made Punjab the majority province in terms of population.1 Mass migrations due to the partition of British India had also stoked ethnic tensions, as Urdu-speaking migrants, or Mohajirs, emigrated from present-day northern India to Pakistan’s Sindh province. This historical context means that the Pakistani state conflates demands for greater civil liberties and provincial autonomy with violent separatist insurgent movements, primarily in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP).

There is a long history of Baloch insurgency against the state in pursuit of greater autonomy or the outright secession of Balochistan, including campaigns waged in 1948, 1958, 1962 and 1973. The return to violence in 2003 started the phase of the insurgency that continues today. Baloch armed groups have split on several occasions and some splinter organisations have demobilised. However, since 2018, these groups have partially set aside their differences to form a coalition with the Baloch Republican Army (BRA) under the banner of the Baloch Raaji Ajoi Sangar (BRAS).

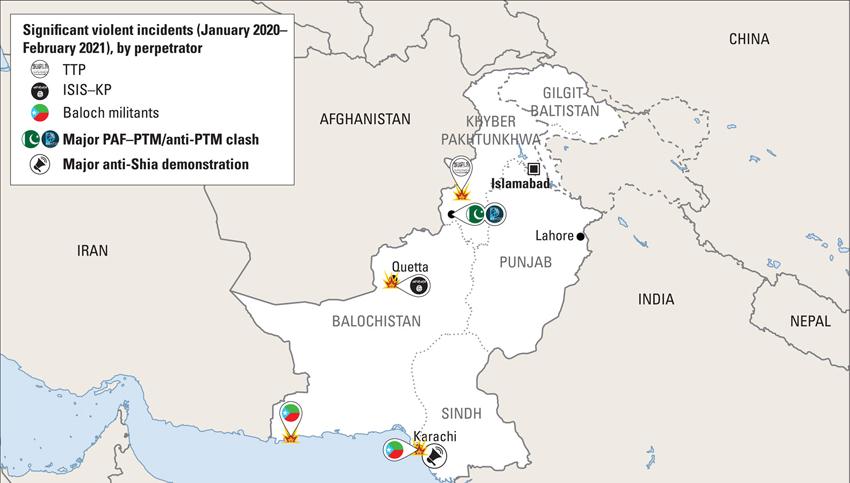

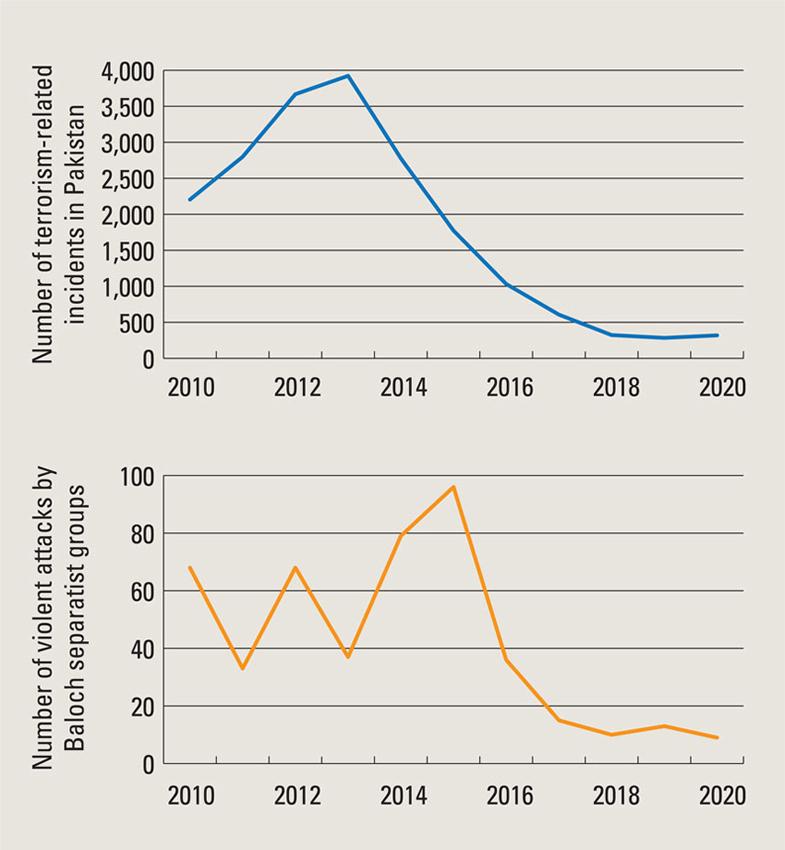

Groups originating in KP, particularly Swat district, and Pashtun tribal areas (formerly known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, FATA) have also taken up arms against the state and the Shia religious minority. An uptick in Pakistani incursions into the then-FATA to target al-Qaeda members following the 9/11 terrorist attacks stoked animosity, and militant groups coalesced to form what is often referred to as the Pakistani Taliban, which in due course became the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Pakistani forces began a counterinsurgency campaign against the TTP in 2009 but initially lacked a coherent strategy. The December 2014 TTP attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar marked an inflection point and prompted the government to draft its first counter-terrorism policy, the National Action Plan (NAP). Operation Zarb-e-Azb and Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad, launched in 2014 and 2017 respectively, led to a significant decrease in insurgent attacks.

ACGRI pillars: ISS calculation based on multiple sources for 2020 and January/February 2021 (scale: 0–100). See Notes on Methodology and Data Appendix for further details on Key Conflict Statistics.

2020 saw an uptick in insurgent activity in Balochistan province and along Pakistan’s western border with Afghanistan. The TTP grew in strength in the former FATA, particularly Waziristan, and attacked military and civilian targets, reversing some of the gains made by Pakistani forces by 2019. The slow progress of reforms following the 2018 merger of the former FATA into KP strained relations between Pashtun tribes and state authorities. The Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) continued to stage protests against alleged abuses of Pashtuns’ human, civil and political rights. Clashes between the movement and Pakistani forces in 2020 were less common than in 2019 but senior PTM members continued to face harassment from the state.

The spread of COVID-19 reawakened centre–province tensions between the federal and provincial governments over the 2010 18th Amendment of Pakistan’s constitution, which had vested significant authority in provincial governments. Prime Minister Imran Khan and Minister for Planning, Development and Special Initiatives Asad Umar argued that it limited the federal government’s ability to respond to the pandemic, among other things. However, provincial governments and opposition political parties largely saw their comments as a blatant attempt by the federal government to reduce provincial autonomy.

Conflict Parties

Pakistan Armed Forces (PAF)

Strength: 651,800 active military, 291,000 active paramilitary.

Areas of operation: Deployed throughout Pakistan (particularly along the Line of Control with India) and against insurgent groups in Balochistan and KP (including the former FATA).

Leadership: General Qamar Javed Bajwa (chief of army staff); Admiral Muhammad Amjad Khan Niazi (chief of naval staff); Air Chief Marshal Mujahid Anwar Khan (chief of air staff); Lieutenant-General Faiz Hamid (Director-General, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI)). ISI falls outside the military command structure but its leaders are drawn from the military and have significant oversight over some operations.

Structure: The PAF consists of nine ‘Corps’ commands, an Air Defence Command and a Strategic Forces Command. Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad involves an array of PAF units that support the police and the Pakistani Civil Armed Forces (PCAF) in counter-terrorism operations.

History: The ongoing Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad succeeded the 2014–17 Operation Zarb-e-Azb. It was launched in response to a resurgence in attacks by TTP splinter group Jamaat-ul-Ahrar. Operation Khyber-4 was launched in 2017 under Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad with the goal of eliminating terrorists in what is now Rajgal valley, Khyber district.

Objectives: Eliminate insurgent groups that threaten the Pakistani state.

Opponents: TTP, Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) and other Baloch separatist groups, ISIS–KP.

Affiliates/allies: PCAF, Pakistani police.

Resources/capabilities: Well-resourced with an array of weapons systems and equipment. The defence budget for 2020 was US$9.3 billion.

Pakistani Civil Armed Forces (PCAF)

Strength: Unknown.

Areas of operation: Throughout Pakistan but most active fighting is against insurgent groups in Balochistan and KP.

Leadership: Funded by the Interior Ministry, although most divisions are commanded by officers seconded from the PAF.

Structure: The main divisions of the PCAF involved in conflict with insurgent groups and participating in the PAF-led Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad are the Frontier Corps (Frontier Corps KP and Frontier Corps Balochistan), the Frontier Constabulary, the Sindh Rangers and the Punjab Rangers. Each group’s authority is limited to its respective geographic area.

History: Contributed to Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad since its establishment in 2017 and to the Special Security Division since 2016. Some outfits within the PCAF, such as the Frontier Corps, have their origins in the period of British colonial rule.

Objectives: Eliminate insurgent groups that threaten the Pakistani state.

Opponents: TTP, BLA and other Baloch separatist groups, ISKP

Affiliates/allies: PAF, Pakistani police.

Resources/capabilities: Primarily equipped with small arms and light weapons, with some shorter-range artillery and mortars.

Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)

Strength: Circa 6,000 in Afghanistan, where the majority of TTP fighters are currently based.2 Strength in Pakistan unknown; recent analysis suggests several thousand.

Areas of operation: Balochistan, KP.

Leadership: Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud (emir and overarching leader), supported by a central shura council.

Structure: Divided by locality into factions, or constituencies, each of which is led by a local emir and supported by a local shura council, which report to the central shura council. Each faction has a qazi (judge) to adjudicate local disputes.

History: Following the 2001 US-led invasion of Afghanistan, al-Qaeda and Taliban militants sought haven in the tribal areas of Pakistan. Operations by the Pakistani – and later by US – forces against al-Qaeda led several groups to form a loose coalition known as the Pakistan Taliban. In 2007, some of these factions unified as the TTP under the leadership of Baitullah Mehsud who was killed in a US airstrike in 2009. A TTP shura elected Hakimullah Mehsud as the organisation’s second emir, but internal divisions grew under his leadership over legitimate targets for attacks and peace talks with the government and worsened under Fazal Hayat (Mullah Fazlullah) between 2013 and 2018, causing several factions to break away, including leaders that formed ISIS–KP in 2014. The 2014 TTP attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar triggered a major PAF counter-offensive, which further weakened the group. Following Hayat’s death in 2018, the leadership reverted to the Mehsud clan under Mufti Noor Wali who sought to reunite and rebuild the group. In 2020, this process culminated with the reintegration of the Hizb-ul-Ahrar, Jamaat-ul-Ahrar and Amjad Farouqi groups and the Hakimullah Mehsud faction into the TTP fold.

Objectives: To defend and promote a rigid Islamist ideology in KP, including in the former FATA.

Opponents: PAF, PCAF.

Affiliates/allies: Afghan Taliban, al-Qaeda.

Resources/capabilities: Has access to small arms and improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Baloch Raaji Ajoi Sangar (BRAS, an alliance that includes the Balochistan Liberation Army, BLA; the Baloch Republican Army, BRA; and the Baloch Liberation Front, BLF)

Strength: Unknown.

Areas of operation: Balochistan.

Leadership: BLA: leadership contested between Hyrbyair Marri and Bashar Zaib; BRA: Brahumdagh Bugti; BLF: Allah Nazar Baloch.

Structure: An alliance of the BLA, BRA and BLF. The BLA is divided into different factions. Pakistan’s government alleges that several factions of the BLA exist and are led by different individuals. The insurgency is deeply divided, with different groups, infighting and fragmentation.

History: The alliance was formed in 2018. The BLA is the largest group and was formed in 2000 under the leadership of Afghanistan-based Balach Marri, who was subsequently killed in an airstrike in Helmand in 2007. Its leadership since then has been subject to additional deaths and significant internal contestation. In July 2019, the US State Department listed the BLA as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist organisation.

Objectives: Seeks independence for the region of Balochistan as a solution to perceived discrimination against the Baloch people. Opposes the extraction of natural resources in Balochistan by Pakistani and foreign actors, especially China, due to the implications of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) for Baloch aspirations.

Opponents: PAF, PCAF.

Affiliates/allies: None.

Resources/capabilities: Attacks by BRAS members have involved small arms and IEDs, including suicide vests and car bombs.

Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISIS–KP)3

Strength: Unclear.

Areas of operation: Balochistan, KP, Afghanistan.

Leadership: Shahab al-Muhajir (emir of ISIS–KP).

Structure: Poorly understood organisational structure. It is likely hierarchical, with an emir at the head, above provinciallevel commanders and a shura council, in turn above district-level commanders and local commanders.

History: The Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) announced the establishment of the ISIS–KP in 2014 by former members of TTP to conduct operations in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Its first four emirs were all killed in US airstrikes in Afghanistan.

Objectives: Like all ISIS factions, ISIS–KP seeks to establish a caliphate and introduce its rigid version of Islamist governance at a local and ultimately regional and national levels. To this end, it seeks to delegitimise the Pakistani state and expel religious minorities from Pakistan.

Opponents: PAF, PCAF.

Affiliates/allies: None.

Resources/capabilities: ISIS–KP attacks have involved small arms and IEDs, including suicide vests.

Conflict Drivers

Political

Ethnic grievances:

Politically mobilised segments of Pakistan’s ethnic minorities accuse the government, the army and the police of targeting them with a campaign of violent repression and marginalisation, with dissidents sometimes facing arbitrary detention, extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. Some groups also accuse the government of depriving them of their fair share of economic resources.

The PTM emerged in its current form in January 2018 to protest the extrajudicial killing of a Pashtun youth by the Karachi police, and its rallies attracted tens of thousands of attendees in 2019. The PTM calls for investigations into forced disappearances, an end to profiling by security services and greater civil liberties for tribal Pashtuns and migrants – positions which have garnered some support outside the movement. Protests were scaled back in 2020 due to pressure from Pakistani authorities and the coronavirus pandemic.

Economic and social

Economic grievances:

Baloch groups allege that the government violates their civil, political and human rights, but also object to Islamabad’s distribution of economic benefits resulting from the extraction of natural resources in Balochistan. CPEC, part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is often referred to as the latter’s pilot project and includes the construction of power plants, mines, highways, railways and improvements to a warm deepwater port in Gwadar. Baloch groups question whether the Baloch people will profit from CPEC or if benefits will instead accrue to China and its partners in the Pakistani government. Baloch insurgents’ strategy of attacking Chinese targets threatens not only CPEC’s progress but also Pakistan’s most important bilateral relationship.

Religious divisions:

Pakistan’s population is 96.28% Muslim according to the country’s Bureau of Statistics, but it does not delineate by sect.4 Estimates suggest that the Sunni population comprises 85–90% and the Shia 10–15%.5 Pakistan’s Sunni Muslims are primarily divided among the Barelvi and Deobandi subsects with a growing Ahl-e-Hadith community. Mainstream Islamist parties and movements representing both Deobandis and Barelvis are united in their support for blasphemy laws, which criminalise acts or statements perceived to malign Islam, particularly the Prophet Muhammad. However, the issue of blasphemy – a chief cause advocated by Barelvi militants and hardliners – has become a driver of radicalisation and violence among Pakistan’s Barelvi Sunnis, which is the largest Sunni subsect in the country.

International

Instability along Pakistan’s borders with Afghanistan and Iran:

Insurgent and terrorist groups have utilised Pakistan’s porous borders to regroup and conduct operations. Baloch separatist groups have previously launched attacks against Iran’s security forces from Pakistan. Cross-border attacks have therefore strained relations between the two countries. The TTP was able to retreat into Afghanistan and the majority of TTP fighters are currently based there. Pakistan has benefitted indirectly from US drone strikes that have killed a number of mid-level and senior TTP commanders in Afghanistan. However, a US withdrawal may limit this capability. Islamabad identifies the safe haven for terrorist groups in Afghanistan as one of the primary drivers of terrorist violence against Pakistan and evidence of Kabul’s complicity. However, this is due more to Kabul’s lack of control over parts of the country’s southeastern provinces, than any sponsor-proxy relationship.

Political and Military Developments

Slow progress towards formalising FATA and KP merger

Attempts to formalise the de jure merger of the administrative and security apparatuses of the former FATA into KP, which began in 2018, continued to move at a slow pace. In 2018, the federal government announced a ten-year development plan for the former FATA, but lawmakers reported that less than 10% of the US$540 million allocated for development in FATA was actually spent in 2019–20.6

The aggressive military and police response to the PTM also undermined progress towards addressing the political and economic marginalisation of the former FATA. The PTM is unpopular among large segments of Pakistan’s population; Pakistani politicians and the military use the ongoing conflict in the former FATA to discredit such movements and suggest the PTM is sponsored by external actors and an enabler of TTP terrorism.

Blasphemy as rallying cry for Islamist groups

In 2020, Islamist groups continued to use the issues of sect and blasphemy to mobilise members and exert power. Islamist political parties in Karachi organised large protests against Shia Muslims in September 2020. Amnesty International reported an uptick in blasphemy accusations, primarily lodged against members of the Shia, Ahmadi and Christian faiths.7 Religious parties continued to actively defend blasphemy laws, particularly the hardline Islamist party Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP). In November 2020, the TLP organised a mass protest in Islamabad over anti-Muslim cartoons that appeared in the French press. The protest prompted Pakistan’s government to sign an agreement with the TLP to boycott French products and delegate to parliament the decision to expel the French ambassador, following a non-binding resolution by the National Assembly to recall Pakistan’s envoy to France in October.

Foreign pressure to step up counter-terrorism measures