2 Europe and Eurasia

Conflict Reports

Overview

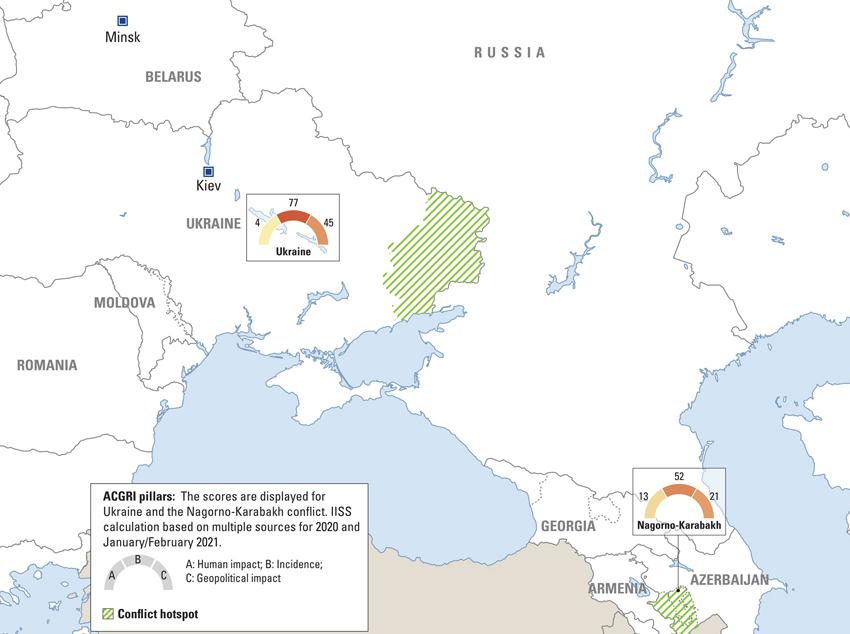

The flashpoints in eastern Ukraine and Nagorno-Karabakh continued to dominate the conflict landscape in Europe and Eurasia. The former saw a build-up of Russian forces along the Ukraine–Russia border in early 2021 that, coupled with an increase in the frequency and intensity of skirmishes and artillery fire, de facto nullified the Minsk ceasefire agreement that entered into force in July 2020.1 Nagorno-Karabakh made international headlines in September 2020 when an outbreak of hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan escalated into a six-week military conflict. As a result, Azerbaijan made significant territorial gains in areas lost to Armenia in previous outbreaks of the conflict.

Both conflicts unfolded along Eurasian geopolitical fault lines, sharing a combination of domestic drivers and regional accelerators. These factors were further compounded by external actors’ influence. While the war in Ukraine is not simply a ‘war in Europe’ but also ‘a war about European security’,2 the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has shown how quickly so-called ‘frozen conflicts’ can reignite, escalate and create long-term consequences.3

Combined, events that took place on these two front lines paint a picture of growing restlessness and geopolitical competition. They also show how escalating crises to de-escalate them has an inherent strategic value, as ultimately does freezing a conflict – as long as military pressure can be maintained. Turkey’s involvement in the Nagorno-Karabakh war and its deployment of advanced technology helped Azerbaijan to escalate and win the military confrontation with Armenia, but also highlighted Ankara’s eagerness to assume a more prominent role at the negotiating table. Russia’s enduring presence in and around eastern Ukraine, coupled with the escalation in military activities of early 2021, highlighted the 2020 Minsk ceasefire’s fragility, and how Moscow can threaten military escalation to stall Kyiv’s attempts to align more firmly with its European and Western partners.

Regional Trends

Interplay of state and non-state actors

Despite new factors that add further layers of complexity to the two conflicts – elements of hybrid and proxy warfare,4 the strategic advantage provided by armed drones and other emerging technologies,5 and the utility of plausible deniability6 – at their core they remain inter-state confrontations for territorial control. In both cases, states are the primary actors. However, this does not mean that non-state actors have not played a role. This is particularly apparent in Ukraine, where both the Ukrainian and pro-Russian fronts have progressively blended state military capabilities, non-state militias and paramilitary forces.7 Recent trends demonstrated how Russia’s diminishing appetite for all-out annexation of the Donetsk and Luhansk ‘people’s republics’ has fragmented separatist entities into ‘a proxy leadership dependent on Moscow’; irredentist militias still fighting to obtain independence or annexation; and the local population, which feels increasingly marginalised by both Ukraine and Russia.8 Against this backdrop, Russia’s military movements in early 2021 may be interpreted as an attempt to restore hopes of independence, or as sabre-rattling aimed at disrupting the ongoing peace talks.9

The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict displayed slightly different characteristics: with the Armenian and Azerbaijani armed forces as the two main belligerents, non-state and quasi-state actors only had a secondary role. The Armenian military is supported by the Artsakh Defence Army (also known as the Nagorno-Karabakh Defence Army, NKDA), the 18,000–20,000-strong, conscript-based military organisation of the (internationally unrecognised) Republic of Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, which suffered significant losses from the Azerbaijani offensive in 2020.

New technologies and actors, old objectives

Azerbaijan reaped the benefits of the massive strategic advantage brought by Turkey’s military support, mainly in the form of armed drones, whose advanced technology could not be matched by Armenian air-defence capabilities.10 In addition, reports have emerged that suggest Turkey brought in Syrian mercenaries to carry out combat and support tasks in Nagorno-Karabakh.11

The conflict hotspots in Europe and Eurasia display some important commonalities: while advanced technology and non-state actors are part of the politico-military equation, at their core these conflicts remain inter-state business, where territorial control is the ultimate goal and the possibility of conventional military escalation is ever present.

Regional Drivers

Political and institutional

Self-determination:

The conflicts in Europe and Eurasia demonstrated the extent to which self-determination remains a key driver – particularly in the post-Soviet world. To a certain degree, events in eastern Ukraine have displayed commonalities with the Georgian–Russian struggle over South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2008,12 highlighting once more the ambiguities and legal grey areas of international law when it comes to the implications of the right to self-determination. In Nagorno-Karabakh, Yerevan’s military adventurism achieved the exact opposite of what Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan had hoped: instead of rallying the Armenian people around the flag of an existential threat to their self-determination, ultimately the consequences stemming from the defeat damaged the government’s legitimacy and worsened political divisions, besides costing Armenia the control of large swathes of Nagorno-Karabakh.13

Pursuit of marginal political gains:

In both conflicts, the pursuit of marginal political gains – rather than long-term strategic objectives – has become a driver in and of itself. The sharp drop in ceasefire violations in eastern Ukraine in 2020 might have signalled that the armed conflict had reached a stalemate, and that progress through military action was perceived as too costly or risky. Alternatively, it may have been a consequence of Russia refocusing on hybrid and non-military activities to achieve marginal political gains without triggering a military escalation. (Its use of soft power and political and civil disruption to stall Ukraine’s progress towards closer alignment with European partners is an achievement in itself.14) While the Novorossiya grand project of annexing eastern Ukraine might have been shelved for now,15 lingering military and political tensions between pro-Russian separatists and the Ukrainian government mean that every decision about the future of the region (and the country as a whole) will require Moscow’s approval. Short-termism has also dictated the pace and evolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh war. Pashinyan’s short-sighted and erratic foreign-policy posturing aimed at drumming up domestic support for his government, coupled with his over-confidence in Armenia’s military strength, were key factors in starting the chain reaction that led to the 2020 war.16 For Azerbaijan, the military escalation provided a unique opportunity to quickly regain control of territories in Nagorno-Karabakh, while also deflecting most of the international pressure to de-escalate the conflict on Armenia.17

Conflict dynamics in the region therefore appear to be driven by an opportunistic rationale. In this sense, the de facto stalemate in the Donbas and the new chapter in the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan are two sides of the same coin. Under certain circumstances, as was the case in Nagorno-Karabakh, armed conflict is likely to re-ignite. Furthermore, the absence of major military operations does not necessarily imply progress towards a resolution, as the situation in eastern Ukraine has demonstrated. Sporadic clashes and skirmishes have punctuated parallel non-military initiatives: Russian artillery strikes have caused growing concerns within Ukraine’s leadership over a possible escalation,18 while Armenia’s deadly attacks against Azerbaijani border outposts in July 2020 were pivotal in fuelling Azeri public support for military retribution, and in pushing Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan even closer to Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev.

Geopolitical

Traditional alliances and geopolitical drivers continued to play an important role in the conflicts. In September 2020, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky approved the country’s new National Security Strategy, centred around reinforcing Ukraine’s partnership with NATO, with membership as the ultimate goal – a major source of concern for Moscow.19 The growing tensions between Azerbaijan and Armenia (that eventually led to the 2020 war) pushed Baku and Ankara closer together, with the latter playing a central role in providing military support to Azeri operations in Nagorno-Karabakh, against the backdrop of a military partnership that goes back decades.20

Regional Outlook

Prospects for peace

As the conflicts in Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine can be described as frozen,21 the distinction between a lack of armed clashes and peace needs to be at the forefront of any meaningful consideration of the prospects for their resolution. Ceasefires are a temporary expedience, and, as the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war demonstrated, years of relative quiet can be followed by a sudden military escalation. Russian armed forces’ deployment as peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh since the November 2020 ceasefire and the agreement signed with Turkey for the creation of a joint observation centre are likely to prevent possible flare-ups in hostilities;22 in addition, from Aliyev’s perspective, the ceasefire is enough to seal Azerbaijan’s successful campaign in Nagorno-Karabakh and avoid opening further negotiations.23 However, the dispute is far from resolved. In eastern Ukraine, aware that any major military offensive may prove counterproductive, both sides rely on the Minsk agreements’ terms that attempt to facilitate a political solution. However, as long as the Luhansk and Donetsk people’s republics exist as semiautonomous political entities, any progress is highly unlikely, as political authority will remain contested between Kyiv and secessionist entities.24

International organisations – the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) above all – are well positioned to contribute to resolution efforts in both conflicts: The OSCE’s Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine has access to the Luhansk and Donetsk people’s republics, although its tasks mainly include monitoring and reporting ceasefire violations. However, its status and effectiveness are undermined by Russia’s involvement (with Russian OSCE observers monitoring Russian military units), which creates frictions and potential conflicts of interest.25

In Nagorno-Karabakh, the OSCE is present through the Minsk Group, which is co-chaired by France, Russia and the United States. It aims to facilitate conflict resolution between Armenia and Azerbaijan. A pivotal entity since its creation in 1992, the Minsk Group now faces strong criticism not only from Armenian leaders, but also from Aliyev and Erdogan, who claim Azerbaijan and Turkey are being sidelined in the ongoing negotiations.26 Promoting Turkey to the status of co-chair, the two leaders claim, would rebalance the group and give new impetus to the negotiations.27 With Yerevan pulling in the opposite direction, it seems unlikely the Minsk Group will survive in its current form.

Escalation potential and spillover risks

The risk of escalation remains moderate in both conflicts. Reports of Russia delivering 650,000 Russian passports to eastern Ukrainians since 2019 have raised concerns in Kyiv and European capitals about a possible escalation of Russian military involvement in the region under the guise of a peacekeeping mission to protect Russian citizens that would de facto consign the Donbas to Russia.28 There is also concern in Baltic countries and within NATO more broadly that Russian influence activities targeting Russian-speaking minorities in other regional states could create new crises.29

Geopolitical changes

The presidency of Joe Biden in the US has the potential to make waves in both conflicts. Zelensky optimistically saluted his election as the catalyst that would ‘help settle the war in Donbas, and end the occupation’,30 while Biden’s April 2021 decision to honour the 2019 US Congress resolution recognising the Armenian genocide – and formally declaring it as such – alienated Turkey.31 Aliyev declared Biden’s remarks ‘unacceptable’, continuing that the United States’ stance would ‘seriously damage cooperation in the region’.32 Both crises are also affected by the dramatic shift in US-Russia relations triggered by Donald Trump’s departure from the White House, as Biden is unlikely to allow Putin the same geopolitical leeway granted by his predecessor.33

Notes

- 1 Andrew E. Kramer, ‘Fighting Escalates in Eastern Ukraine, Signaling the End to Another Cease-fire’, New York Times, 30 April 2021.

- 2 International Crisis Group (ICG), ‘Peace in Ukraine I: A European War’, Europe Report no. 256, 28 April 2020, p. i.

- 3 See, for example, Svante E. Cornell (ed.), The International Politics of the Armenian–Azerbaijani Conflict: the Original ‘Frozen Conflict’ and European Security (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

- 4 Mark Galeotti, ‘Hybrid, Ambiguous, and Non-linear? How New Is Russia’s “New Way of War”?’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, vol. 27, no. 2, 21 March 2016, pp. 282–301.

- 5 Zachary Kallenborn, ‘Drones Are Proving to Have a Destabilizing Effect, Which Is Why Counter-Drone Systems Should Be a Key Part of US Military Aid to Partners’, West Point Modern War Institute, 9 December 2020.

- 6 Adam Lammon, ‘Nagorno-Karabakh: Why Turkey Is Sending Syrian Mercenaries to War in Azerbaijan’, National Interest, 29 September 2020.

- 7 On Russia, see Galeotti, ‘Hybrid, Ambiguous, and Non-linear? How New Is Russia’s “New Way of War”?’; on Ukraine, see Andreas Umland, ‘Irregular Militias and Radical Nationalism in Post-Euromaydan Ukraine: The Prehistory and Emergence of the “Azov” Battalion in 2014’, Terrorism and Political Violence, vol. 31, no. 1, 26 February 2019, pp. 105–31.

- 8 ICG, ‘Rebels Without a Cause: Russia’s Proxies in Eastern Ukraine’, Europe Report no. 254, 16 July 2019, p. 11.

- 9 Olena Prokopenko, ‘Ukraine’s Fragile Reform Prospects amid Ongoing Russian Aggression’, German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF), 28 May 2021.

- 10 Michael Kofman and Leonid Nersisyan, ‘The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, Two Weeks in’, War on the Rocks, 14 October 2020.

- 11 Liz Cookman, ‘Syrians Make Up Turkey’s Proxy Army in Nagorno-Karabakh’, Foreign Policy, 5 October 2020.

- 12 For context, see ICG, ‘Georgia and Russia: Why and How to Save Normalisation’, Crisis Group Europe Briefing, no. 90, 27 October 2020.

- 13 Laure Delcour, ‘The Future of Democracy and State Building in Post-conflict Armenia’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 19 January 2021.

- 14 See, for example, Kateryna Zarembo and Sergiy Solodkyy, ‘The Evolution of Russian Hybrid Warfare: Ukraine’, Center for European Policy Analysis, 29 January 2021.

- 15 ICG, ‘Rebels Without a Cause: Russia’s Proxies in Eastern Ukraine’, p. 8.

- 16 Michael A. Reynolds, ‘Confidence and Catastrophe: Armenia and the Second Nagorno-Karabah War’, War on the Rocks, 11 January 2021.

- 17 Philip Remler et al., ‘OSCE Minsk Group: Lessons from the Past and Tasks for the Future’, OSCE Insights, 29 December 2020, p. 6.

- 18 Kramer, ‘Fighting Escalates in Eastern Ukraine, Signaling the End to Another Cease-fire’.

- 19 Taras Kuzio, ‘The Long and Arduous Road: Ukraine Updates Its National Security Strategy’, Commentary, Royal United Services Institute, 16 October 2020.

- 20 Haldun Yalçinkaya, ‘Turkey’s Overlooked Role in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War’, GMF, 21 January 2021.

- 21 Tom Mutch, ‘Nagorno-Karabakh Is Moscow’s Latest Frozen Conflict’, Foreign Policy, 20 May 2021.

- 22 ‘Turkey, Russia Sign Joint Observation Center Agreement for Nagorno-Karabakh’, Daily Sabah, 1 December 2020.

- 23 Philip Remler et al., ‘OSCE Minsk Group: Lessons from the Past and Tasks for the Future’, p. 9.

- 24 Thomas de Waal and Nikolaus von Twickel, ‘Scenarios for the Future of Eastern Europe’s Unresolved Conflicts’, in Michael Emerson (ed.), Beyond Frozen Conflict: Scenarios for the Separatist Disputes of Eastern Europe (London: Rowman and Littlefield International, 2020), pp. 31–2.

- 25 Paul Niland, ‘Russia Has No Place in the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine’, Atlantic Council, 23 July 2018.

- 26 ICG, ‘Improving Prospects for Peace after the Nagorno-Karabakh War’, Crisis Group Europe Briefing, no. 91, 22 December 2020.

- 27 ‘Azerbaijan Wants Turkey to Co-chair Minsk Group’, TWTWorld, 12 October 2020.

- 28 Peter Dickinson, ‘Russian Passports: Putin’s Secret Weapon in the War Against Ukraine’, Atlantic Council, 13 April 2021.

- 29 Josh Rubin, ‘NATO Fears That This Town Will Be the Epicenter of Conflict with Russia’, Atlantic, 24 January 2019.

- 30 Steven Pifer, ‘The Biden Presidency and Ukraine’, Brookings Institution, 28 January 2021.

- 31 Thomas De Waal, ‘What Next After the US Recognition of the Armenian Genocide?’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 30 April 2021.

- 32 Andalou Agency, ‘Biden’s Remarks Unacceptable, Historical Mistake: Azerbaijan’s Aliyev’, Daily Sabah, 24 April 2021.

- 33 Robert Kagan, ‘The United States and Russia Aren’t Allies. But Trump and Putin Are’, Brookings Institution, 24 July 2018.

Source: IISS

Overview

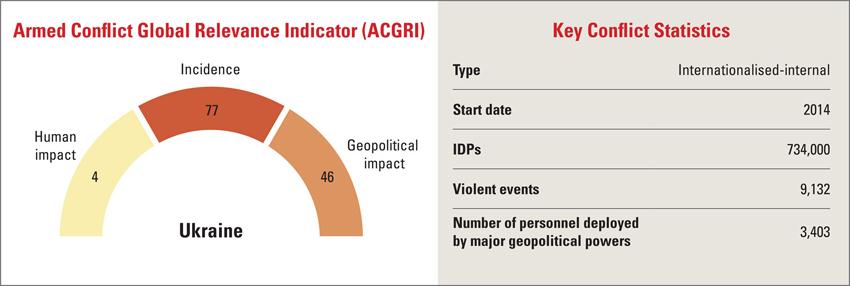

2020 represented the seventh year of the conflict in Ukraine, following its outbreak in 2014, when Russia’s armed forces intervened to annex Crimea and to support the separatist armed groups of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR). In the first year of the war the battlefield was dynamic, with territory forcibly changing hands between the Ukrainian armed forces and Russian-backed separatists. In subsequent years, the war has settled into a pattern of ongoing hostilities that wax and wane in intensity, and that unfold across an increasingly static Line of Contact. The conflict continues to fuel tensions between Russia on one side, and European states and the United States on the other.

In parallel to the fighting has been the Minsk peace process, which is based on the Minsk Protocol (5 September 2014) and a supplementary package of measures known as ‘Minsk II’ (12 February 2015). Progress has been made in implementing some of its provisions such as on prisoner exchanges. However, an enduring end to the hostilities remains elusive. One complication faced by the Minsk accords is that they name the LPR and DPR as conflict parties but not Russia, despite the latter’s vital role in supporting the separatist groups. Russia’s role has instead been enshrined as one of the ‘Normandy Four’ alongside France, Germany and Ukraine at the highest level of conflict-resolution diplomacy. To break the impasse around implementing the Minsk accords, the ‘Steinmeier formula’ was proposed in 2016 to suggest steps to grant Donetsk and Luhansk some autonomy. This was accepted by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in 2019 on the condition that other aspects of the Minsk accords would first be implemented. The matter of sequencing these steps has been mired in conflicting interpretations by Russia and Ukraine.

Intermittent fighting and inconclusive negotiations continued in 2020 and early 2021. A ceasefire came into effect on 27 July 2020 and largely held for several months, before beginning to break down towards the end of 2020. The working-level forum for talks on de-escalation continued to be the Trilateral Contact Group (TCG), chaired by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), with representatives from Ukraine and Russia, plus the DPR and LPR. The TCG met regularly during this period, but its work remained inconclusive.

The conflict was overshadowed by a Russian military build-up in March and April 2021, in which large amounts of military personnel and equipment were moved into Crimea and near the Russia–Ukraine border. While Moscow said that it had massed these personnel for a snap military exercise, the event was widely interpreted as a coercive gambit intended to signal Russia’s ability to ratchet up the level of tension surrounding the conflict in Ukraine. By late April, the fear of a Russian escalation had diminished as the additional forces were withdrawn.

Conflict Parties

Ukrainian armed forces

Strength: 209,000 active military personnel including 145,000 in the army, 45,000 in the air force and 11,000 in the navy.

Areas of operation: Along the 500-kilometre Line of Contact in the Donbas region of Ukraine.

Leadership: In March 2020, President Zelensky divided the posts of commander-in-chief and chief of the general staff to bring Ukraine in line with NATO principles. The commander-in-chief is the professional head of the armed forces and is Lieutenant-General Ruslan Khomchak. The chief of the general staff is Lieutenant-General Serhiy Korniychuk. General Volodymyr Kravchenko is commander of the Joint Forces in Donbas.

Structure: Divided into four regional HQs. In 2020, the Ukrainian government announced a range of ongoing reforms to defence structures, including a division of responsibilities to relieve pressure on the General Staff by establishing four new commands: Joint Forces Command; Communication and Cyber Security Forces Command; Support Forces Command; and Medical Forces Command.

History: Severely unprepared at the start of the war, a significant modernisation process has taken place since 2014, mobilising a large army with advanced equipment.

Objectives: In 2020, holding the current front line has been more of a priority than the previous strategy of slowly regaining territory along the Line of Contact, as seen in 2018 and 2019.

Opponents: DPR, LPR.

Affiliates/allies: US, European Union, Poland and NATO (as of 2020).

Resources/capabilities: In 2020, Ukraine’s defence budget was US$4.35 billion, an increase from US$3.97bn in 2019, and approaching double the amount before the start of the war in 2013 when it was US$1.88bn. The Ukrainian air force fields an estimated 188 fixed-wing aircraft including 71 fourth-generation fighters (Su 27s and MiG 29s). The Ukrainian army fields 1,820 artillery pieces and 3,246 armoured fighting vehicles including 858 main battle tanks.

Donetsk People's Republic (DPR)

Strength: The number of active-duty personnel is unknown.

Areas of operation: Across the Line of Contact in the Donetsk region.

Leadership: Led by Denis Pushilin since November 2018.

Structure: Since 2014, the multiple militias operating across Donetsk have been integrated into the main DPR force. The DPR has sought to demonstrate that it can perform governmental functions in the occupied territories, and originally formed 16 specialised committees tasked with working on bills. It has a parliamentary body, the People’s Council, as well as localised governmental bodies, such as city administrators and ‘local soviets’. The DPR has drawn up a constitution, issued its own vehicle number plates, changed the currency to the Russian rouble from the Ukrainian hryvnia and instituted Russian as the official regional language.

History: Formed by the protesters and volunteers of the Maidan Revolution protests across Donetsk in 2014, who proclaimed the DPR in June 2014 after seizing government buildings and assets.

Objectives: The DPR has changed its strategy throughout the conflict but hopes to achieve autonomy for the Donetsk region by breaking away from Kyiv and becoming either a province of Russia or an independent state.

Opponents: Ukrainian armed forces.

Affiliates/allies: LPR, Russia.

Resources/capabilities: Difficult to ascertain, though much equipment was captured from Ukrainian forces and shipped from Russia.

Luhansk People's Republic (LPR)

Strength: The number of active-duty personnel is unknown.

Areas of operation: Across the Line of Contact, particularly in the Luhansk region.

Leadership: Leonid Pasechnik since November 2017.

Structure: Appears less centralised than the DPR, with several armed groups retaining power in various parts of the occupied Luhansk territory.

History: Emerged from the same events that resulted in the formation of the DPR.

Objectives: Similar to the DPR but aimed at the Luhansk region.

Opponents: Ukrainian armed forces.

Affiliates/allies: DPR, Russia.

Resources/capabilities: Difficult to ascertain, though much equipment was captured from Ukrainian forces and shipped from Russia.

Pro-Kyiv paramilitaries

Strength: Disparate groups including Azov, Dnipro and Donbas battalions. Their strength is unknown, and some battalions have been integrated into the Ukrainian armed forces.

Areas of operation: Azov battalion active in Zolote.

Leadership: A complex relationship exists between the paramilitary battalions and the Ukrainian armed forces. Some battalions have been fully integrated into the Ukrainian armed forces and Ministry of Internal Affairs. Others have retained more independence, such as the Dnipro battalion which has been funded by the oligarch Igor Kolomoisky.

Structure: Variable between the battalions, with some having used more formalised hierarchical structures and others structured in a more ad hoc way.

History: Volunteer battalions were formed following the Maidan Revolution to mobilise against pro-Russian separatists in the east.

Objectives: Fight back against the DPR, LPR and Russian forces in Ukraine. Different pro-Kyiv paramilitary battalions have had more specific territorial and ideological objectives that reflect where they have operated, their sources of funding, and their levels of internal discipline.

Opponents: DPR, LPR.

Affiliates/allies: Ukrainian armed forces.

Resources/capabilities: Unknown.

Russian armed forces and Russian private military contractors

Strength: The number of Russian armed forces operating in the Donbas is unknown. Also unknown is the balance between regular armed-forces personnel, special-forces and military-intelligence personnel, and private military contractors.

Areas of operation: Likely to either be fully embedded in DPR and LPR forces or fighting independently in the same areas of operation as the DPR and LPR.

Leadership: Unknown.

Structure: Unknown.

History: Since 2014 investigative reports have highlighted the presence of Russian armed-forces personnel fighting in Ukraine. Moreover, numerous Russian armed-forces personnel have been captured as prisoners of war by the Ukrainian authorities. Moscow continues to deny the involvement of its soldiers in the conflict.

Objectives: In accordance with an undeclared Russian government policy, to occupy and wage war in parts of Ukrainian territory as part of a low-intensity armed conflict that has the wider aim of disrupting Ukrainian sovereignty.

Opponents: Ukrainian armed forces.

Affiliates/allies: DPR, LPR.

Resources/capabilities: Unknown.

Conflict Drivers

Political

The Maidan Revolution:

Popular protests began in Ukraine at the end of 2013 after Russian pressure led then-president Viktor Yanukovych to reverse his plans to sign an association and free-trade agreement with the EU. The protesters, wanting greater integration between Ukraine and the EU, perceived the Yanukovych presidency as having pivoted towards Russia. Known as the Maidan Revolution (‘Revolution of Dignity’), the protests were also fuelled by longer-term drivers of discontent such as opposition to corruption and political nepotism. Yanukovych was deposed in February 2014 and subsequently fled the country. A coalition of opposition parties, Batkivshchyna (Fatherland) and the far-right Svoboda, formed the post-Maidan government. The Maidan Revolution was centred around Kyiv and was supported in other parts of Ukraine, notably in western cities like Lviv. However, it exacerbated some regional divisions within the country and sparked counterprotests elsewhere in Ukraine.

In the eastern Donbas region (including Donetsk and Luhansk), an initial seizure of government buildings coalesced into a separatist movement supported by Russia. Anger at the way in which Yanukovych had been deposed was one factor, but the separatist movement was also fuelled by longer-term discontent, specifically the poor economic outlook of the region due to the increasing unprofitability of the heavy industry it relied on, and by the underlying tensions and misperceptions between Donbas residents and other parts of Ukraine.

Economic and social

Intra-Ukrainian tensions:

A degree of alienation had developed between Donbas inhabitants and Kyiv after independence. Periodic tensions arose around the coexistence of the Ukrainian and Russian languages for instance, with some Donbas residents perceiving that Ukrainian nationalism had marginalised their Russian-leaning heritage. Economic tensions focused on the distribution of wealth by successive governments in Kyiv and the industrial Donbas region. Once a thriving heavy-industry heartland during the Soviet era, the local economy of the Donbas had been reduced to a rust-belt territory in the years leading up to the conflict. Its coalmines, fertiliser plants and other industrial facilities had become less profitable due to corruption, mismanagement and the obsolescence of production methods.

Security

Crimea accession to Russia and conflicting narratives:

The Ukrainian government mobilised its army, augmented by nationalist volunteer battalions from the Maidan Revolution, to counter the rising threat from pro-Russian separatists. The blockade of the Donbas territories by the Ukrainian government, and escalating fighting, caused significant loss of life and displacement around the areas where the pro-Russian separatists had proclaimed the Donetsk and Luhansk ‘people’s republics’ (DPR/LPR). Concurrently, Russian troops without insignia were deployed at strategic points in the Ukrainian Crimean Peninsula on 27 February 2014. The Crimean parliament held a referendum on 16 March that allegedly demonstrated overwhelming support for Russian accession by the Crimean people, though the conduct of the referendum was criticised by foreign governments. Russia formally claimed sovereignty over Crimea on 18 March 2014. Ukraine has depicted the war as an attempt to defend its territory from Russian aggression, while the pro-Russian separatists have argued that they are protecting their citizens from ‘fascists’ in Kyiv.

International

Regional influences:

While intra-Ukrainian tensions were unlikely themselves to degenerate into war, the intervention by Russia provided the decisive spark. Russia had various motivations for intervening. Domestically, in 2014, the outbreak of war and the seizure of Crimea boosted President Vladimir Putin’s popularity. Geopolitically, Ukraine became a battleground in Russia’s attempts to assert its regional power, as it seeks to avert Ukraine’s hypothetical future memberships in the EU and NATO.

Political and Military Developments

Change of negotiators

In January 2020, during Putin’s cabinet reshuffle, Vladislav Surkov was replaced as Russia’s chief political-military adviser and representative on the Ukraine conflict by Dmitry Kozak, who in 2003 had tried to broker a deal between Moldova and Transnistria. The Ukrainian government also changed its key appointments to the talks, with former president Leonid Kuchma replaced in the TCG by another former president, Leonid Kravchuk. Oleksii Reznikov also became Ukraine’s Minister for the Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories.

Continued fighting

The first half of 2020 saw intermittent fighting around several hotspots, notably three areas in the Donetsk region (around Donetsk airport; east of Mariupol; around Svitlodarsk) and one area in the Luhansk region (between Popasna, Zolote and Pervomaisk). Some signs suggested a slowing down in fighting, yet military activity persisted along the Line of Contact, including the continued deployment of heavier weapons – in violation of the Minsk Protocol – especially in non-government-controlled areas of the Donbas.

Ceasefire brokered

The coronavirus pandemic precluded some inperson talks, resulting in a virtual meeting of the Normandy Four in April 2020, before an in-person meeting in Berlin on 3 July. A virtual meeting of the TCG on 22 July yielded an agreement over the implementation of a comprehensive ceasefire, containing ‘measures to strengthen the ceasefire’ and a ‘coordination mechanism’ to report violations. In November, the TCG agreed to four new disengagement zones: in Luhansk’s villages of Petrivka, Slovyanoserbsk and Nyzhnoteple, and near Hryhorivka in Donetsk.

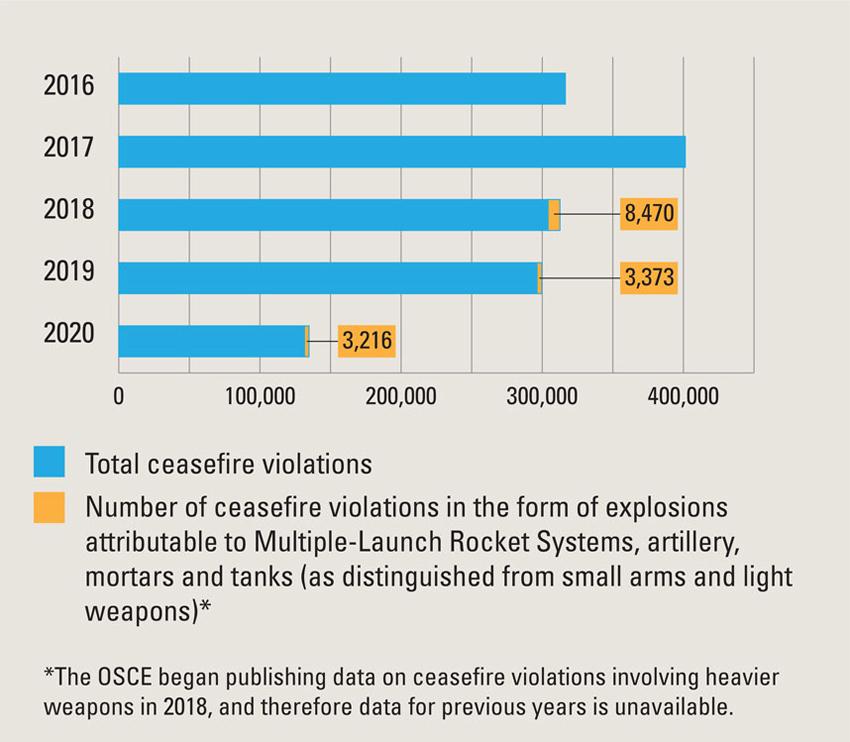

Fluctuating ceasefire violations

The ceasefire that came into effect on 27 July initially seemed effective, with ceasefire violations progressively and significantly decreasing: from 60,188 in the first quarter, to 56,879 in the second, 13,977 in the third and 3,723 in the fourth quarter. The daily average of ceasefire violations fell almost 20-fold after July 27 (623 to 33 respectively).1 However, by the end of 2020 the ceasefire had come under strain as the OSCE reported over 200 ceasefire violations in the Donetsk region on three separate days (11, 19 and 29 December). In the first quarter of 2021, a total of 8,676 ceasefire violations were recorded by the OSCE, indicating a return to regular hostilities along the Line of Contact.2

Local council elections

Local council elections were held on 25 October 2020, except in the areas controlled by the Russian-backed separatists due to the prevailing political and security conditions. Other parts of Donetsk and Luhansk under Ukrainian-government control were also excluded from voting under the advice of civil–military administrators.

Russia's military build-up

In late March 2021, Russia moved a large amount of its military personnel, weapons systems and equipment into Crimea and into its western regions bordering Ukraine, notably Rostov and Voronezh. The total number of Russian military personnel massed close to Ukraine was estimated at 100,000, supposedly for a snap military exercise, as explained by Russian Defence Minister Sergey Shoygu.3 However, the Ukrainian government, the EU and NATO interpreted these actions as Russia either flexing its military muscle in a show of strength or preparing for a military incursion. Tension and uncertainty around Russia’s intentions remained high until late April, when Russia declared the end of its exercise and began to withdraw the additional forces.

Key Events in 2020–21

POLITICAL EVENTS

29 January 2020

Dmitry Kozak replaces Vladislav Surkov as Moscow’s lead negotiator on Ukraine.

11 February

Andriy Yeramak replaces Andriy Bohdan as Kyiv’s Head of Presidential Office.

16 March

Amid the spread of COVID-19, all entry–exit checkpoints along the Line of Contact close.

30 April

A virtual meeting of the Normandy Four is held.

13 May

Kozak visits Berlin to discuss next steps on conflict resolution with German officials.

12 June

NATO makes Ukraine an Enhanced Opportunities Partner on inter-operability issues.

30 July

Leonid Kravchuk replaces Leonid Kuchma as Ukraine’s chief envoy to the Minsk talks.

4 August

Kravchuk suggests ‘special status of administration’ for DPR/LPR, who reject this.

25 October

Local elections held nationwide, excluding parts of Donetsk and Luhansk.

27 October

Ukraine’s Constitutional Court outlaws the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption (NACP).

11 November

Russia rejects Ukraine’s ‘joint steps’ proposal to demilitarise the conflict zone.

29 December

Zelensky suspends Constitutional Court head Oleksandr Tupytskyy.

28 January 2021

‘Russia Donbas Forum’ held in Donetsk city.

3 February

Zelensky bans three pro-Russian TV channels and extends Tupytskyy’s suspension.

MILITARY/VIOLENT EVENTS

18 February 2020

Spike in fighting near Zolote disengagement area in Luhansk.

22 April

The TCG meets as fighting continues unabated by the coronavirus pandemic.

8 May

The United Nations appeals for de-escalation as fighting continues to claim lives.

27 July

‘Full and comprehensive ceasefire’ comes into effect at 00:01.

12 August

Although hostilities substantially decrease, one Ukrainian soldier is killed.

28 August

The ceasefire broadly holds, but two Russian-backed separatist fighters are killed.

6 September

Ceasefire still broadly holding, but one Ukrainian soldier killed in Luhansk.

29 December

Ceasefire under pressure in a third day of escalating hostilities in this month.

31 January 2021

Further fighting in Donetsk hotspots during the month as the ceasefire wanes.

19 February

The OSCE reports a particularly high tally of 594 ceasefire violations in Donetsk.

Impact

Human rights and humanitarian

The war claimed 24 lives and injured 105 people in 2020. Half of these deaths and injuries were inflicted by mines and unexploded ordnance, with the rest inflicted by shelling or small arms and light weapons.4

There were 734,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Ukraine as of February 2021.5 Housing, employing and integrating these IDPs in their host communities remained an ongoing process. The coronavirus pandemic exacerbated the privations already suffered by many IDPs and by people who live near the war zone as quarantine restrictions and travel limitations were introduced and the five crossing points along the Line of Contact were closed.

In a prisoner swap ahead of Orthodox Easter, 20 Ukrainians were returned to Kyiv from detention by the Russian-backed separatists, who in turn received 14 people held by the Ukrainian authorities. Ukrainian prisoners in the DPR and LPR remained an agenda item for the Normandy Four, with discussions on potential access to these prisoners being given to the International Committee of the Red Cross. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) reported that while its staff had unimpeded access to official places of detention in governmentcontrolled territory, such access was denied in the DPR and LPR territories.

Political stability

The war caused some disenfranchisement in the October 2020 local council elections. Ukraine’s Central Election Commission announced in August that voting would not be held in ten communities in the Donetsk region and eight in the Luhansk region, on the government-controlled side of the Line of Contact, based on the advice of the civil–military administration of these areas. Nationwide turnout for the election was 36.88%, with Zelensky’s party, Servant of the People, securing 15.05% of local deputies. Second place went to Fatherland with 10.63%, and third place to the Opposition Platform – For Life with 9.91% (the latter party being broadly sympathetic towards Russia).6 The low turnout, and the fragmentary outcome, reflected the enduring hold of local allegiances, as well as the relative success of decentralisation reforms since 2014.

President Zelensky, in his second year in office, faced challenges in implementing two of his major campaign pledges: ending the war and fighting corruption. In October, the Constitutional Court curbed the powers of the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption, which had been created after the Maidan Revolution. This prompted criticism from the US Embassy in Kyiv, which expressed concern on behalf of Ukraine’s international partners and donors. The Court reinstated the agency’s powers, but tensions persisted between Zelensky and the head of the court, Oleksandr Tupytskyy, who was suspended and later dismissed by Zelensky in 2021.

Economic and social

The conflict has had a catastrophic impact on Ukraine’s economy, resulting in rising inflation and poverty rates as well as years of macroeconomic contraction. The coronavirus pandemic added further pressure on Ukraine’s economy, which shrank by 4.2% in 2020.7 Consumer inflation was forecast by the National Bank of Ukraine to reach 7% as of year-end 2021.8

In November 2020, the World Bank approved a US$100 million project to support ‘Ukraine’s efforts to promote socio-economic recovery and development of Eastern Ukraine with these funds earmarked for the government-controlled areas in the Luhansk region’.9 The region’s heavy industry remained mainly located in separatist-controlled areas, and the conflict had prevented those in government-controlled areas who might have previously travelled across the region for work to access these jobs. Many residents of the Donbas fled once the war began, with some from the separatistcontrolled areas moving to Russia, while others were displaced internally within Ukraine. On both sides of the Line of Contact, some of the Donbas residents who remained in their homes have become dependent on economic opportunities from the mixture of legal and illicit trade across the front line. The economy of the separatist-controlled areas has suffered, with the properties in Luhansk city losing around half their value since the war began.

Relations with neighbouring and international partners and geopolitical implications

Ukraine–Russia relations remained in a dire condition due to Russia’s role in the war. Russia’s past use of military contractors in Ukraine resulted in a well-publicised incident in neighbouring Belarus, as authorities in Minsk arrested 33 contractors on 29 July 2020 reportedly from the Russian private military company the Wagner Group. President Zelensky demanded that Ukraine take custody of 28 of these contractors, including nine who had Ukrainian passports, while the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s office cited the Wagner Group’s past role in the Donbas war. However, all but one of those arrested were sent back to Russia (the remaining individual held Belarusian citizenship). Although it is not possible to estimate the scale of past Russian military-contractor involvement in the Ukraine war, their utility to the Russian government is clear, given the close links between private military companies like Wagner and the Russian state, and the benefits of deniability that military contractors offer to Russia instead of deploying its regular soldiers abroad.10 Ukraine also remained concerned by signs of Russia extending its security presence in the region, as it sought to deepen its defence ties to Belarus, including through joint military drills and by exploring the possibility of basing Russian troops in Belarus.

Conflict Outlook

Political scenarios

Although the 27 July ceasefire demonstrated that a significant de-escalation in the fighting could be achieved, the peace process remained blocked by persistent disagreements over the ultimate status and level of political autonomy of the DPR-and LPR-controlled areas. On this matter there is little sign of an immediate breakthrough in the respective positions of Russia and Ukraine. Moscow still accuses Kyiv of a reluctance to fully implement the Minsk accords; conversely, Kyiv remains politically constrained, given the domestic criticism that this would attract. The likely outlook is of a continuing peace process stymied on the core issues that could end the conflict.

An indication of Russia’s sentiments regarding the Donbas came on 28 January 2021, at the ‘Russia Donbas Forum’ held in DPR-controlled Donetsk city attended by Russian senator Kazbek Taysaev, DPR leader Denis Pushilin and LPR leader Leonid Pasechnik. Margarita Simonyan, chief executive of the RT news channel, made a direct emotional appeal, declaring: ‘Mother Russia, take Donbas home’.11 However, Putin’s press secretary later distanced the Kremlin from the event, saying that integrating the Donbas into Russia was not a policy worth pursuing. Nevertheless, the event conveyed a public doubling-down of Russia’s material and ideological hold over the region and reflected a Russian line of thinking against returning the LPR and DPR to Ukrainian government control. Ukraine’s former president Kravchuk promised in February 2021 to raise the Russia Donbas Forum in the TCG negotiations.

Escalation potential and conflict-related risks

The possibility of escalation cannot be precluded, especially after the concern raised by Russia’s massing of its armed forces near its border with Ukraine in March–April 2021. The eventual withdrawal of these forces rather than their deployment into Ukraine suggests that Russia’s intention in this instance was to intimidate Ukraine rather than to seek additional military gains. One possibility is that Russia wants to step up measures to integrate the separatist-controlled Donbas areas, which have been in place for years – for example the DPR and LPR adopted Moscow’s time zone in 2014 – without escalating its existing military involvement.

Prospects for peace

The conflict defies straightforward characterisation as either an invasion, a proxy war, an insurgency or a civil war – featuring some constituent properties of each, even if the parties to the conflict may prefer to use only one of these terms. The mix of local, regional and international drivers, and Russia’s incentives around the war, present continuing obstacles to conflict resolution.

The OSCE has monitored the ceasefire since 2014 from its patrol hubs, vehicle patrols, uninhabited aerial vehicles and cameras. As a monitoring mission, its leverage over the conflict parties is low, and it can only offer an off-ramp from the war if the parties come to an agreement. The OSCE’s reporting provides an order-of-magnitude overview of the war. The 134,767 ceasefire violations it reported in 2020 were a steep decline from recent years.12 It remains to be seen whether the overall number of ceasefire violations recorded in 2021 will continue this annual downward trajectory.

Source: OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine

Strategic implications and global influences

Several regional and international developments have been of consequence to the conflict. On 12 June 2020, NATO recognised Ukraine as an Enhanced Opportunities Partner, reflecting the past contribution made by Ukrainian troops in NATO missions in Kosovo and Afghanistan. This status granted Ukraine access to inter-operability exercises and equipment programmes, although it did not confer a commitment to future Ukrainian membership of NATO. In parallel, Ukraine set out several reforms to its military apparatus. In March 2020 Zelensky announced the separation of the armed forces leadership roles of chief of the general staff and commander of the armed forces, in line with NATO principles. Other changes to Ukraine’s military training, leadership structures and equipment procurement were also announced.13

The US diplomatic line with Russia became tougher since President Biden’s administration came to power in January 2021. An early step was the announcement of a US$125m military aid package comprising training, equipment and advisory assistance, including ‘defensive lethal weapons’ to improve the Ukrainian military’s ability to defend against ‘Russian aggression’.14

Tensions around the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project in 2020–21 had some bearing on Ukraine’s regional position. The first Nord Stream pipeline already connects Russia’s gas supplies to Europe via the Baltic Sea, and Nord Stream 2 would greatly increase Russia’s capacity to bypass Ukraine when exporting its gas. Ukraine perceives the German-backed Nord Stream 2 as an anti-Kyiv project, intended by Russia to deprive it of future revenue from the transit of gas and to make it more vulnerable to Russia. With the Biden administration’s criticism of Nord Stream 2, Germany came under pressure to recalibrate its support for the project and mooted an idea by which it would agree to shut off Nord Stream 2 if Russia used it to put pressure on Ukraine.

Notes

- 1 Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine, ‘January – March 2020 Trends and Observations’; ‘April – June 2020 Trends and Observations’; ‘July – September 2020 Trends and Observations’, 28 January 2021.

- 2 Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine, ‘January – March 2021 Trends and Observations’, 5 May 2021.

- 3 ‘Russia: Speech by High Representative/Vice President Josep Borrell at the EP Debate’, European Union External Action Service, 28 April 2021.

- 4 Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine, ‘2020 Trends and Observations’, 28 January 2021.

- 5 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, ‘Ukraine: Country Fact Sheet’, February 2021.

- 6 Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, ‘Ukraine, Local Elections, 25 October 2020: ODIHP Limited Election Observation Mission Final Report’, 29 January 2021, pp. 33, 36, 42.

- 7 International Monetary Fund, ‘World Economic Outlook Database’, April 2021.

- 8 National Bank of Ukraine, ‘Speech by NBU Governor Kyrylo Shevchenko at a Press Briefing on Monetary Policy’, 21 January 2021.

- 9 World Bank, ‘New World Bank Project to Help with Economic Recovery and Development of Eastern Ukraine’, 6 November 2020.

- 10 See ‘Russia’s use of its private military companies’, IISS Strategic Comments, vol. 26, no. 39, December 2020.

- 11 Alvydas Medalinskas, ‘Kremlin TV Chief: Russia Must Annex East Ukraine’, Atlantic Council, 9 February 2021.

- 12 Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine, ‘2020 Trends and Observations’. There are distinctions in ceasefire violations, and the OSCE specified that of the 134,767 violations in 2020, 3,216 involved ‘explosions attributable to MLRS (Multiple Launch Rocket Systems), artillery, mortars and tanks’, as distinguished from small arms and light weapons.

- 13 Government of Ukraine, ‘National Defence’.

- 14 United States Department of Defense, ‘Defense Department Announces $125M for Ukraine’, 1 March 2021.