NAGORNO-KARABAKH

Sources: IISS; Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation; Le Monde; BBC Research; Prime Minister of Armenia; Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Azerbaijan; Syrian Observatory for Human Rights; Syrians for Truth and Justice

Overview

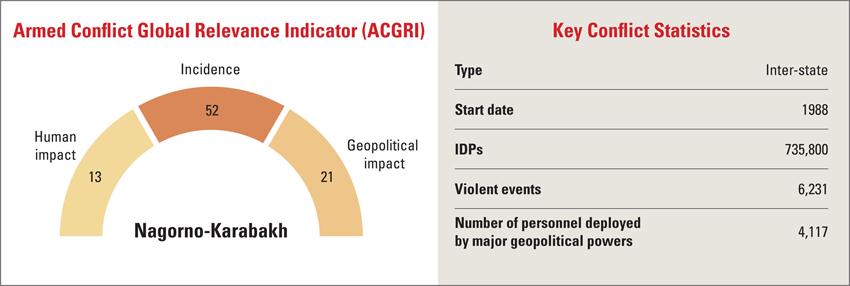

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is a dispute over a mountainous area of some 4,400 square kilometres that formed part of Soviet Azerbaijan, but which has a majority ethnic Armenian population. The conflict is one of several in the former Soviet Union frequently depicted in terms of clashing principles of self-determination and territorial integrity, and featuring an unrecognised, secessionist entity or ‘de facto state’, in this case the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR), also known as the Republic of Artsakh, which remains unrecognised by any United Nations member, including Armenia.

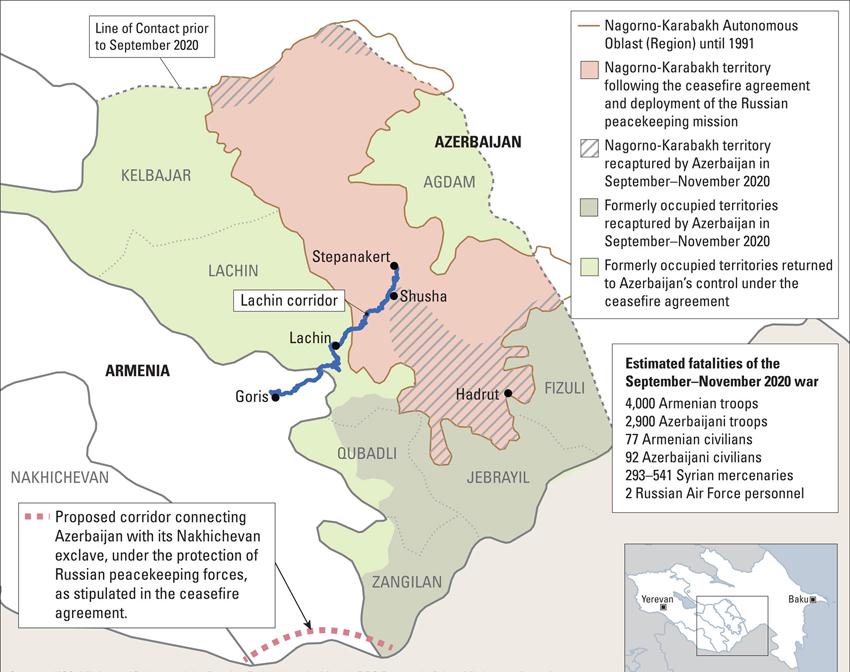

In 1987 Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian population began a campaign to separate from Azerbaijan and unify with Armenia. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the subsequent power vacuum, an ongoing low-level conflict escalated into a full-scale war between Azerbaijan and Armenia-supported Nagorno-Karabakh, which ended in 1994 with a decisive Armenian military victory and a Russian-brokered ceasefire agreement. Armenian forces took control of almost all of Nagorno-Karabakh itself while occupying several surrounding regions not originally part of the dispute, and an approximately 200-km Line of Contact was established between the two forces. The Minsk Group, which was created by the Conference on (later the Organization for) Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE/OSCE), has been mediating Armenian–Azerbaijani negotiations since 1992.

Since the mid-2010s, low-intensity violence has continued, punctuated by occasional major escalations such as the April 2016 ‘four-day war’. In 2020, another major escalation took place, with clashes in July along the Armenia–Azerbaijan border to the north of Nagorno-Karabakh, followed by the September onset of a full-scale 44-day war along the Line of Contact. This time Azerbaijan prevailed – with significant Turkish support – restoring control over most of the territories it had lost to Armenian forces in the early 1990s, including approximately one-third of the territory originally under dispute in Nagorno-Karabakh itself.

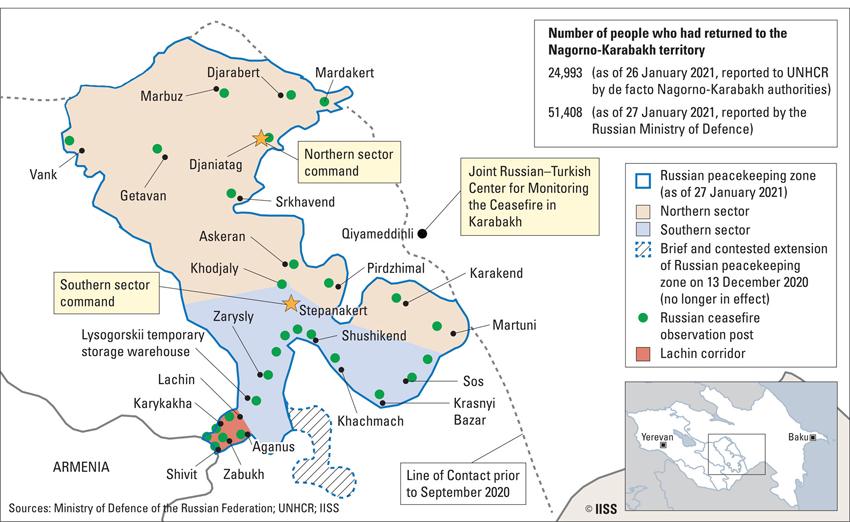

A Russian-mediated ceasefire brought the war to an end on 10 November 2020. The agreement included the deployment of a peacekeeping force, provided by Russian Ground Forces, for a minimum of five years to those parts of Nagorno-Karabakh not recaptured by Azerbaijan and the Lachin corridor linking Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. Also agreed was the Armenian withdrawal from occupied territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, the exchange of prisoners between all parties and an Armenian safety guarantee for transit across southern Armenia between mainland Azerbaijan and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhichevan.

Conflict Parties

Azerbaijani armed forces

Strength: 66,950 active-service personnel in Azerbaijan’s conscript-based armed forces and an estimated 300,000 reservists. Military service lasting 18 months (12 months for university graduates) is mandatory for able-bodied males aged 18–35.

Areas of operation: Prior to, and during, the 2020 war, the bulk of Azerbaijani forces were deployed along the Line of Contact. Troops were also deployed to Azerbaijan’s Nakhichevan exclave.

Leadership: President Ilham Aliyev (commander-in-chief); Colonel-General Zakir Hasanov (minister of defence).

Structure: The majority of troops serve in Azerbaijan’s land and air forces. A small navy comprising some 2,200 service personnel is based on the Caspian Sea.

History: Independent Azerbaijan’s armed forces were established in 1991–92 from Soviet army units and Azerbaijani militias. The army’s slow and disorderly formation contributed to its defeat at the hands of Armenian forces in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Significant military expenditures have substantially upgraded capabilities since then.

Objectives: In 2020, defend and restore Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

Opponents: Armenian armed forces; Nagorno-Karabakh Defence Army (NKDA).

Affiliates/allies: Azerbaijan and Turkey have cooperated closely on defence and security since the early 1990s and Turkish support was key to Azerbaijan’s military success in 2020.

Resources/capabilities: Azerbaijan has modernised its military through supplies from Israel, Russia and Turkey, among others. In 2020, Azerbaijan’s defence budget was US$2.27 billion (approximately 5.32% of GDP), a significant increase from the US$1.79bn in 2019. Azerbaijan has supremacy over Armenia in most areas, particularly uninhabited aerial vehicles (UAVs). Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones delivered in summer 2020 played a major role in the subsequent war.

Armenian armed forces

Strength: 45,000 service personnel, around half of whom are conscripts. Reservists currently stand at 210,000 members. Military service lasting 24 months is mandatory for males aged 18–27, including dual nationals residing abroad. Although exact figures are unavailable, several units composed of reservists served with the Armenian army during the 2020 war.

Areas of operation: Mainly deployed along the international border with Azerbaijan.

Leadership: Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan (commander-inchief); Vagharshak Harutyunyan (minister of defence).

Structure: Armenia’s armed forces – comprising five army corps, air and air-defence forces – have close ties to the NKDA, although a separate command structure is maintained.

History: Ex-Soviet Army corps and volunteer paramilitary units fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh formed the basis for the Armenian armed forces, officially established in 1991 following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Objectives: Before the 2020 war, to provide extended deterrence to the de facto jurisdiction of the NKR. After the 2020 war, to protect the country’s territorial integrity.

Opponents: Azerbaijani armed forces; Turkish armed forces.

Affiliates/allies: Armenia is a founding member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation. It is also covered by extended deterrence through bilateral agreements with Russia, which has a military base with an estimated 3,300–5,000 troops in Gyumri, near the Turkish border.

Resources/capabilities: In 2020 Armenia’s defence budget was US$613 million (approximately 4.97% of GDP), registering a decline relative to 2019’s US$644m. Russia is Armenia’s main arms supplier; Soviet-era stock in some items was still in use in 2020.

Nagorno-Karabakh Defence Army (NKDA)

Strength: Until 2020, an estimated 18,000–20,000 personnel served in the armed forces of the unrecognised NKR. Over half the troops are thought to have been Armenian citizens.1

Areas of operation: Prior to the 2020 war, the NKDA was deployed along the heavily fortified Line of Contact. Troops were also deployed to the occupied territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh proper. During the 2020 war they were deployed along the Line of Contact and the main battle areas in Fizuli, Jebrayil, Zangilan, Lachin and Nagorno-Karabakh.

Leadership: Arayik Harutyunyan, Nagorno-Karabakh’s de facto president since March 2020, is commander-in-chief. Lieutenant-General Jalal Harutyunyan was defence minister from 24 February until he was wounded on 27 October 2020. He was replaced by Lieutenant-General Mikael Arzumanyan. Decisions on defence and security are taken by the Artsakh Security Council; Vitaly Balasanyan, a 1990s war veteran, general and former presidential candidate, is its secretary.

Structure: The majority of personnel serve in the NKDA’s ground forces.

History: Established in 1992 from local paramilitary units engaged in small-scale fighting with Soviet and Azerbaijani forces in the early 1990s.

Objectives: The primary objective before the 2020 war was to defend Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding occupied territories against Azerbaijani attack.

Opponents: Azerbaijani armed forces and their affiliates.

Affiliates/allies: Closely integrated with the Armenian armed forces although they maintain a separate chain of command.

Resources/capabilities: The NKR receives financial subsidies from Armenia, although the proportion of this dedicated to military spending is unknown. Armenia has also supported the NKDA through military training and education.

Russian Armed Forces

Strength: 1,960 peacekeepers.2

Areas of operation: The bulk of Russian peacekeepers are deployed along the Lachin corridor and the eastern and southern areas of Nagorno-Karabakh not recaptured by Azerbaijan in 2020. Russia also maintains a military presence including several bases in Armenia. In the aftermath of the 2020 war, Russian border guards established several outposts in southern Armenia near the border with Azerbaijan.

Leadership: President Vladimir Putin (supreme commander-in-chief); Sergey Shoygu (minister of defence).

Structure: Most peacekeeping units currently stationed in Nagorno-Karabakh belong to the 15th Separate Motor Rifle Brigade of the Central Military District (Russian Ground Forces). Border guards operating under Federal Security Service (FSB) command are currently deployed in both Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.

History: Deployed to Nagorno-Karabakh following the ceasefire signed on 10 November 2020.

Objectives: Ceasefire monitoring in Nagorno-Karabakh for a minimum of five years, subject to renewal if neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan states their intention to terminate the agreement. FSB border guards have been instructed to guarantee transport links between Azerbaijan and its Nakhichevan exclave as set out in the ceasefire agreement.

Opponents: n/a.

Affiliates/allies: Russia and Armenia are founding members of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation. Obligations include extended deterrence, although guarantees do not extend to Nagorno-Karabakh.

Resources/capabilities: Russian peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh have light weapons and at least 90 armoured personnel carriers and 380 units of special equipment including vehicles at their disposal. Russia’s military presence in Armenia is accompanied by advanced-weapons systems; since 2020, this likely includes several Iskander short-range ballistic missiles.3

Turkish Armed Forces (TSK)/Turkish-backed Syrian private military contractors

Strength: Strong evidence suggests that Turkey deployed 1,500–2,500 Syrian private military contractors (PMCs) to fight for Azerbaijan in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, although both countries have denied this.4 It has been alleged that Turkish personnel participated directly in the Azerbaijani campaign, including as operators of some of the Turkish-made drones deployed by Baku.5 One Turkish general and approximately 40 servicemen have operated a joint Russian-Turkish ceasefire monitoring facility since January 2020 in the Agdam region of Azerbaijan.6

Areas of operation: Syrian fighters were reportedly deployed to the front line during the 2020 war, in particular to the southern flank of the Azerbaijani offensive.

Leadership: President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (commander-in-chief); General (retd.) Hulusi Akar (minister of national defence); General Yasar Guler (chief of general staff).

Structure: The command structure for Syrian units deployed to Nagorno-Karabakh is unclear. Sources suggest Syrian PMCs were mainly recruited through the Syrian National Army, a Turkish-backed force opposed to President Bashar al-Assad.

History: Turkish-backed PMCs were reportedly dispatched to Nagorno-Karabakh in late September 2020 in waves, before or just after the start of the war.

Several hundred Turkish military personnel allegedly remained in Azerbaijan following joint military exercises in July–August 2020 and were, according to some reports, later involved in the operation in Karabakh.

Objectives: Support Azerbaijan’s military campaign.

Opponents: NKDA, Armenian armed forces.

Affiliates/allies: Azerbaijan.

Resources/capabilities: Turkish-backed Syrian PMCs fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh were thought to have been extremely poorly equipped.

Conflict Drivers

Political

Unresolved legacies of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War:

The First Nagorno-Karabakh War of 1992–94 left significant legacies that remained prominent in the domestic politics of both Armenia and Azerbaijan. In the case of Azerbaijan, the occupation of significant swathes of territory and the seemingly permanent forced displacement of internally displaced persons remained consistent sources of grievance. For Armenia, the establishment of an unrecognised republic, or ‘de facto state’, in Nagorno-Karabakh was perceived as the only alternative to the loss of the territory’s Armenian identity in the absence of any credible commitments to self-governance for its Armenian population within Azerbaijan.

Security

Militarisation:

Conflicting Armenian and Azerbaijani commitments to, respectively, retaining or restoring control over Nagorno-Karabakh increasingly intersected with rising militarisation. Bolstered by oil revenues, from the mid-2000s Azerbaijan engaged in a comprehensive overhaul of its military involving substantial arms purchases from a variety of suppliers, notably Israel, Russia and Turkey. Armenia reciprocated through embedding itself within a Russian extended deterrent, hosting a Russian base in its second-largest city Gyumri and other Russian military installations. Yet while Russia’s extended deterrence covered the territory of the Republic of Armenia, it has never been framed as including the contested territory in Nagorno-Karabakh – creating a grey zone in Armenia’s own deterrent and reducing the costs for Azerbaijan of military action. After 2014, regular escalations and skirmishes became common along both the Line of Contact and the internationally recognised border between Armenia and Azerbaijan to the north.

International

Declining multilateralism:

Growing securitisation of the Line of Contact narrowed the space for the negotiations mediated by the OSCE’s Minsk Group. After a significant escalation along the Line of Contact in April 2016, Armenia and Azerbaijan agreed to a number of measures to strengthen the ceasefire and move to more substantive talks; none were implemented. Within the Minsk Group, France and the United States effectively defaulted to de facto Russian leadership of the process. Perceiving the risks of a major war testing its deterrent capacity, from 2015 Russia unsuccessfully sought the conflict parties’ agreement to a peace-plan variant – sometimes referred to as the ‘Lavrov plan’ after Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov – involving the deployment of a Russian peacekeeping mission to Nagorno-Karabakh. In 2020 the OSCE experienced a leadership crisis, as the 57-member organisation failed to agree on mandates for the heads of its Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, High Commissioner on National Minorities and the Representative on Freedom of the Media (RFoM), leaving these posts unfilled for several months. Azerbaijan was one of the states that objected to the candidacy of Harlem Desir in the role of RFoM.

Rising multipolarity:

The decline of multilateral diplomacy left a vacuum increasingly filled by rising regional powers. In the South Caucasus neighbourhood, Russia and Turkey have increasingly projected power into the Middle East, North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. While indirectly confronting each other through local actors in Syria and Libya, and occasionally coming to direct blows, Russia and Turkey are also aligned in advancing their respective capacities for structural and strategic autonomy from Euro-Atlantic powers and the associated liberal international order. In the Armenian–Azerbaijani context, Russia is deeply embedded with both countries in a variety of roles, including as an arms provider, trading partner and mediator. Turkey has traditionally provided moral support to Azerbaijan, with which it has close ethnolinguistic ties; conversely, Turkey has a highly conflicted history and no diplomatic relations with Armenia. These factors inhibited Turkish diplomacy vis-à-vis the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, leaving the option of a more militarised strategy of the kind seen in 2020.

International distraction:

In 2020 global distraction due to the coronavirus pandemic combined with a number of other events to divert international attention, which offered a window of opportunity for military action. Protests in Belarus that began in May and escalated in August served to distract Russian attention from the South Caucasus and, at least at their onset, to illustrate the fragility of authoritarian rule in the region. The US was also distracted by presidential elections, which in turn presented regional actors with the prospect of a new president less sympathetic to Russia and Turkey.

Political and Military Developments

Instability in domestic politics

In February 2020 snap parliamentary elections in Azerbaijan – seemingly intended to counter unfavourable comparisons with Armenia’s 2018 democratic breakthrough – did not result in the changes that many observers expected. In Armenia, controversy surrounded Prime Minister Pashinyan’s efforts to indict figures associated with the previous regime under the Republic Party of Armenia (RPA), notably former president Robert Kocharian, on charges associated with civil disorder in March 2008. Kocharian’s trial was the first of a former incumbent in the post-Soviet space, becoming a point of tension in Pashinyan’s already tense relationship with Vladimir Putin.

Tensions and symbolic politics

Bilateral relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan had already deteriorated early in 2020. This signalled the definitive end to a perceived opening in 2019 following an announcement by the Minsk Group that both countries’ foreign ministers had agreed, after a meeting in Paris in January, on the necessity of ‘preparing populations for peace’. This rhetoric was already faltering by summer 2019 as no breakthrough materialised. A tense public meeting between President Aliyev and Prime Minister Pashinyan at the Munich Security Conference in February 2020 ended in familiar historical claim and counter-claim. In May, the inauguration of de facto Karabakh leader Harutyunyan in Shusha (spelled Shushi by Armenians), a crucial symbolic site for Azerbaijanis, and announcements suggesting that Shusha could become the territory’s political capital, sparked offense in Azerbaijan. This was compounded in June when approval was given for a third road across the occupied territories connecting southern Armenia and southern Karabakh, casting further doubt on the likelihood of these territories ever passing back to Azerbaijani jurisdiction.

Clashes along the international Armenia–Azerbaijan border

On 12 July 2020, cross-border clashes broke out along the international Armenia–Azerbaijan border in the Tavush/Tovuz area, killing 17 – mostly Azerbaijanis – over the following days. Protests calling for war began near Baku after 12 July, and escalated after two high-ranking officers, Major-General Polad Hashimov and Colonel Ilgar Mirzayev, were killed. Reactions to these deaths resulted in an unprecedented, spontaneous street protest in Baku on 14 July demanding more muscular military action against Armenia. Azerbaijani foreign minister Elmar Mammadyarov was dismissed following severe public criticism from President Aliyev of the OSCE-mediated negotiations process. Mammadyarov was replaced by education minister Jeyhun Bayramov.

Increased Turkish–Azerbaijani cooperation

Increased Turkish support for Azerbaijan was evident in the aftermath of the July clashes, with Azerbaijani and Turkish defence officials meeting repeatedly and visibly, and senior Turkish officials, including Minister of Defence Hulusi Akar, publicly issuing threats to Armenia.7 The full extent of Turkish military support to Azerbaijan in 2020 remains unknown and contested. Following joint military exercises with the Azerbaijani armed forces in July, substantial materiel and hundreds of servicemen and military advisers reportedly remained in the country in readiness for subsequent deployment.8 Some of these may have operated newly delivered Bayraktar TB2 drones during the subsequent war, which were used to significant tactical effect. While Ankara and Baku deny having employed Syrian foreign fighters in Nagorno-Karabakh, their presence in the region was widely reported in international media, and the Syrian Observatory of Human Rights claimed that over 540 Syrian mercenaries died in hostilities between September and November.9

War breaks out

Azerbaijan launched large-scale offensive operations along the Line of Contact on 27 September 2020, focused on the Armenians’ more vulnerable southern flank, striking population centres and spurring intense fighting. By mid-October Azerbaijan had made substantial territorial gains, wresting control of a number of Armenian-controlled districts surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, bringing the town of Hadrut in Nagorno-Karabakh proper under its control, and advancing along the Azerbaijani–Iranian border. On 8 November, Azerbaijan cemented its victory by taking the symbolically and strategically important town of Shusha. After several failed attempts at a ceasefire, the fighting was finally ended by a Russian-brokered trilateral agreement on 10 November after 44 days of war. This agreement was enforced by a Russian peacekeeping mission rapidly deployed to Nagorno-Karabakh.10

Key Events in 2020–21

POLITICAL EVENTS

15 February 2020

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev meet in a tense live debate at the Munich Security Conference.

28 February

First case of COVID-19 is reported in Azerbaijan.

1 March

First case of COVID-19 is reported in Armenia.

31 March

Elections in the unrecognised NKR proceed despite the onset of the coronavirus pandemic; incumbent Arayik Harutyunyan is re-elected.

21 May

In Nagorno-Karabakh, de facto leader Arayik Harutyunyan’s inauguration takes place in Shusha, a city of symbolic importance to Azerbaijanis.

14 July

Unprecedented popular protest in the Azerbaijani capital Baku, calling for military action against Armenia.

3 September

Deputy chairman of the Azerbaijani opposition Musavat party, Tofig Yaqublu, is sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for ‘hooliganism’ after an altercation he claimed was staged.

10 October

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov announces a humanitarian ceasefire, which fails almost immediately.

17 October

A second ceasefire, negotiated by France under the auspices of the OSCE’s Minsk Group, is announced and fails.

25 October

A third ceasefire, negotiated by the US under the auspices of the OSCE’s Minsk Group, is announced and fails.

20 November

The formerly occupied (and uninhabited) Azerbaijani city of Agdam returns to Azerbaijani jurisdiction, followed by the region of Kelbajar on 25 November and the region of Lachin on 1 December; the French Senate votes to recognise the NKR.

11 January 2021

At a meeting with President Vladimir Putin in Moscow, Aliyev and Pashinyan agree to the establishment of a working group that will select infrastructure and border-opening projects for presentation by March 2021.

MILITARY/VIOLENT EVENTS

12 July 2020

Cross-border clashes break out along the international Armenia-Azerbaijan border in the Tavush/Tovuz area, killing 17 over the following days, including a popular Azerbaijani general.

21 July

Armenian and Azerbaijani demonstrators clash at a rally in Los Angeles.

23 July

Armenian–Azerbaijani street fighting in Moscow leads to up to 30 arrests.

27 September

Azerbaijan launches offensive operations along the Line of Contact, with missile and artillery strikes on several population points in Nagorno-Karabakh continuing over the following weeks. Intense fighting ensues.

4 October

The Azerbaijani city of Ganja is hit by ballistic missiles, in the first of four missile strikes that claim 26 lives in total.

5 October

Use of cluster munitions to bombard Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital Stepanakert is documented; use by both sides is later documented.

9 October

After making significant territorial gains over preceding days, Azerbaijan captures the town of Hadrut in Nagorno-Karabakh on or around this date.

18 October

Azerbaijani armed forces advance as far as the Khudaferin bridge on the Azerbaijan–Iran border.

27–28 October

The Azerbaijani city of Barda is hit by ballistic missiles, in the first of three missile strikes that claim 27 lives in total.

8 November

Azerbaijani forces take the town of Shusha after intense fighting.

10 November

A Russian–Armenian–Azerbaijani ceasefire declaration ends the war, as a Russian peacekeeping mission is rapidly deployed to Nagorno-Karabakh.

11 December

Clashes break out in a cluster of villages near Hadrut that had remained under Armenian control despite encirclement. The villages later passed to Azerbaijani control.

Impact

Human rights and humanitarian

The 2020 war, though short, wrought a devastating humanitarian impact. There were some 6,000 confirmed fatalities among Armenian and Azerbaijani combatants at the time of writing, while the total is most likely higher than 7,000, with more than 10,000 wounded, in addition to some 170 fatalities among civilians.11 Approximately 130,000 people were displaced, some 90,000 of them Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh.12 Numerous reports of human-rights violations against civilians and war crimes were recorded. Hundreds of prisoners were taken during and just after the fighting, with many Armenian prisoners still unaccounted for as of the time of writing. Indiscriminate attacks hitting hospitals, schools, religious sites and other civilian infrastructure were also recorded on each side of the conflict, as well as the use of cluster munitions, which pose long-term risks to local populations of being maimed or killed by explosive remnants. With civilians crowding into basements and temporary accommodation to escape the fighting, the war coincided with an eightfold increase in COVID-19 cases in Armenia.13 Meanwhile, the return of Azerbaijanis displaced by the First Nagorno-Karabakh War to former front-line areas now under Azerbaijani control was constrained by extensive destruction in these areas and the presence of a substantial number of mines and unexploded ordnance.

Political stability

In Armenia, the defeat created an enduring political crisis. Pashinyan’s signing of the agreement which saw Armenia turn over significant swathes of territory on top of that already lost militarily to Azerbaijan was met with fury from large segments of the population. His continued presence in post sparked months of protest and even the prospect of civil–military tensions as senior army officers openly called for his resignation, until he conceded to holding snap elections, scheduled for June 2021. By contrast, military victory further strengthened the position of Aliyev in Azerbaijan, despite escalating restrictions on civil liberties during the coronavirus pandemic.

Economic and social

The war further radicalised already polarised societies. In both Armenia and Azerbaijan, pro-peace voices were silenced through harassment and targeting by the authorities. Real-time coverage of events on the front line and videos showing summary killings and beatings circulated across social media, generating public outrage. The war had devastating economic impacts on all parties involved, and particularly on the local economy in Nagorno-Karabakh itself, which had a small but reportedly vibrant economy estimated to be worth $713m in 2019.14 The fighting caused heavy damage to infrastructure, including the loss of road links to Armenia on which the territory formerly depended, which will heavily constrain Armenia’s ability to provide needed resources and have long-term impacts on Nagorno-Karabakh’s viability as an economic entity.

Relations with neighbouring and international partners and geopolitical implications

The 2020 war established significant new geopolitical dynamics in the South Caucasus as the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict became yet another theatre where Russia and Turkey are actively engaged. Russia now shares responsibility with Turkey for managing the ceasefire monitoring centre, located in Azerbaijan’s Agdam district to the east of Nagorno-Karabakh. This Russian–Turkish duopoly represents a new ‘regionalisation’ of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, with Moscow and Ankara working together in a symbiotic relationship to marginalise Euro-Atlantic actors and other international organisations in general and the OSCE in particular.

Turkey’s penetration of the South Caucasus reciprocates Russia’s own entry into the conflicts in Libya and Syria. It also represents an assertive challenge to Russia’s presumed hegemony in the former-Soviet sphere. While playing only a secondary role in monitoring the ceasefire, Turkey nevertheless stands to benefit strategically from the new guarantee of transit across southern Armenia that will connect it to Azerbaijan and Central Asia – assuming that sufficient momentum is sustained for the corridor to be constructed.

If no longer the sole outside player, Russia remains the dominant one. The war’s outcome permitted a new military presence in the South Caucasus, and substantially increased Russian leverage over both Azerbaijan and Armenia, while excluding Euro-Atlantic powers. Russia’s responses demonstrated significant tactical flexibility and successfully averted outcomes less favourable to Moscow. Yet Russia’s insertion into the context both represented a substantial escalation of its commitments and posed new challenges for its bilateral relationship with each of the parties. Russia will likely face countervailing pressures regarding its presence, with Azerbaijan wishing to limit its duration and Armenia to extend it.

Other neighbouring states struggled to contain overspill from the conflict and maintain friendly relations with both Armenia and Azerbaijan. Georgia’s offer to broker peace talks was not accepted, and the country was later accused in Armenian media reports of facilitating the transit of Azerbaijani military supplies.15 Renewed Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict also threatened radicalisation among Georgia’s own Armenian and Azerbaijani national-minority populations. The strengthening of Russia’s presence in the South Caucasus is seen in Georgia through the lens of Tbilisi’s own territorial conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia/Tskhinvali district, which are recognised by the vast majority in the international community as parts of Georgia but by Russia and a handful of aligned states as independent from Georgia. The prospect of an alternative corridor running through Armenia also threatens the monopoly that Georgia has held on east–west transit since the 1990s.

Iran also offered good offices for Armenian–Azerbaijani negotiations to no avail. Iran’s own ethnically Azerbaijani population – located in the northwest of the country just south of the conflict zone – increasingly voiced support for Azerbaijan in the 2020 war. While Iran’s political leadership responded to pro-Azerbaijani protests in Tabriz and other cities with rhetorical support for Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, increased Turkish presence in the South Caucasus and the significant role played by Israeli weaponry in Azerbaijan’s military victory were not welcomed in Tehran.

Conflict Outlook

Political scenarios

The political outlook remained extremely uncertain. The 10 November 2020 ceasefire declaration resolved only some of the issues previously under negotiation in the OSCE-mediated Minsk Group process. Official rhetoric suggests that Azerbaijan considers the conflict resolved as it focuses on the rehabilitation of the de-occupied territories. However, the absence from the ceasefire declaration of the core issue that drives the conflict, the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, and the marginalisation of the OSCE Minsk Group negotiations, drive Armenian concerns over whether and how this issue can be reopened. Neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan abandoned belligerent postures. The post-war situation continued to be inflamed by several issues, notably Azerbaijan’s detention of dozens of prisoners amid reports of their deaths and torture;16 Azerbaijani fatalities owing to landmines in de-occupied areas; and the alteration and destruction of Armenian cultural and community heritage in areas restored to Azerbaijani control.

Escalation potential and conflict-related risks

While the ceasefire largely held, the new status quo brought various security risks. The mandate of the Russian peacekeeping mission in Nagorno-Karabakh remained to be defined, and while renewable if neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan objects, it had a formal five-year lifespan. Further ambiguities surrounded the Armenian armed forces in the territory: while all its units were required to withdraw in the 10 November 2020 declaration, the status of Karabakh-Armenian armed units of the NKDA remained unclear. The 2020 war and its outcome dissolved the previous context of long-distance segregation of Armenians and Azerbaijanis. In a variety of theatres from Nagorno-Karabakh itself to southern areas on either side of the international Armenia-Azerbaijan border, representatives of each nationality were brought into closer proximity than at any time since the early 1990s.

Prospects for peace

Prospects for a negotiated peace remain dim, with Armenia and Azerbaijan continuing to hold opposite views and the stalling of the formal negotiations process mediated by the OSCE’s Minsk Group. In the absence of a multilateral peace process, Russia continues to pursue a trilateral format aimed at implementing the measures foreseen in the 10 November 2020 declaration, including a working group tasked with identifying new infrastructure and communications projects.

Sources: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation; UNHCR; IISS

Strategic implications and global influences

The 2020 war marked a significant inflection point in the history of the conflict by resituating it as a theatre of contestation by regional powers Russia and Turkey, rather than a theatre of mediation and conflict resolution by an international coalition. Regionalisation was demonstrated in the post-war period by Russia’s leading role in negotiations with Armenia and Azerbaijan, overseeing the implementation of the 10 November 2020 agreement. It remained unclear whether, under what conditions, and with what agenda the OSCE Minsk Group talks might resume.

Notes

- 1 Sergey Minasyan, Sderzhivanie v Karabakhskom Konflikte [Deterrence in the Karabakh Conflict] (Yerevan: Caucasus Institute, 2016), pp. 266–9.

- 2 ‘Russia Sends Nearly 2,000 Peacekeepers to Nagorno-Karabakh, Defense Ministry Says’, TASS, 10 November 2020. The International Crisis Group subsequently reported a total of ‘some 4,000 Russian soldiers and emergency services staff’. See International Crisis Group, ‘Post-war Prospects for Nagorno-Karabakh’, Report no. 264, 9 June 2021, p. i.

- 3 In 2019, Russian officials announced plans to double the combat potential of the 102nd Russian military base in Gyumri without increasing the number of personnel.

- 4 ‘After Azerbaijani Government’s Refusal of Their Settlement, Over 900 Turkish-backed Mercenaries Return to Syria’, Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, 2 December 2020; and Ed Butler, ‘The Syrian Mercenaries Used as “Cannon Fodder” in Nagorno-Karabakh’, BBC News, 10 December 2020.

- 5 Elena Chernenko, ‘Prinuzhdenie k konfliktu’ [Compelled into Conflict], Kommersant, 16 October 2020.

- 6 ‘Turkish–Russian Center Begins Monitoring Nagorno-Karabakh Truce’, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 30 January 2021.

- 7 Amberin Zaman, ‘Turkish Defense Minister Vows to “Avenge” Azerbaijanis Killed in Armenian Attacks’, Al-Monitor, 16 July 2020.

- 8 Chernenko, ‘Prinuzhdenie k konfliktu’.

- 9 Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, ‘Death Toll of Mercenaries in Azerbaijan Is Higher Than That in Libya, While Syrian Fighters Given Varying Payments’, 3 December 2020. See also Butler, ‘The Syrian Mercenaries Used as “Cannon Fodder” in Nagorno-Karabakh’; and Syrians for Truth and Justice, ‘Government Policies Contributing to Growing Incidence of Using Syrians as Mercenary Fighters’, 2 November 2020.

- 10 ‘Zayavlenie Prezidenta Azerbaydzhanskoy Respubliki, Prem’er-ministra Respubliki Armenii, i Prezidenta Rossiyskoy Federatsii’ [Statement by the President of the Azerbaijani Republic, Prime Minister of Armenia and President of the Russian Federation], 10 November 2020.

- 11 For the civilian and lower combatant figure, see International Crisis Group, ‘The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: A Visual Explainer’, 7 May 2021; the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) identifies 6,706 fatalities for Armenia and Azerbaijan in 2020 as a whole. The latest official data as of this writing suggests that 2,895 Azerbaijanis were killed in action (including deaths from landmines after the ceasefire). Estimates of Armenians killed in action have been more variable, with 4,000 cited by officials as a likely approximate total. See ‘Azerbaijan Updates Death Toll in Karabakh’, Caucasian Knot, 9 May 2021; and ‘Pashinyan Says About 4,000 Armenian Troops Killed in Nagorno-Karabakh’, TASS, 14 April 2021.

- 12 United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Bachelet Warns of Possible War Crimes as Attacks Continue in Populated Areas’, 2 November 2020.

- 13 Comment, ‘War in the Time of COVID-19: Humanitarian Catastrophe in Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia’, The Lancet, vol. 9, no. 3, 1 March 2021, E243–E244.

- 14 ‘Nagorno-Karabakh’s Record Growth in Ruins Amid Conflict and Pandemic’, DW, 12 October 2020.

- 15 ‘Arms Transit Reports to Azerbaijan “Disinformation,” Georgia Says’, civil.ge, 5 October 2020.

- 16 ‘Azerbaijan: Armenian POWs Abused in Custody’, Human Rights Watch, 19 March 2021.