CHAPTER

20

The Role of the Internal Coach

THE TERM EXECUTIVE COACH CONJURES AN IMAGE OF A PROFESSIONAL ENGAGING WITH CLIENTS IN A VARIETY OF ORGANIZATIONS, BUT THIS IMAGE DOES NOT FULLY REFLECT THE REALITY OF HOW COACHING IS DELIVERED. AS mentioned in the previous chapter, coaching services are increasingly provided by professionals internal to the organizations in which they work. Our definition of executive coaching in Chapter 3 encompasses both internal and external coaching engagements, and several of the case examples in Part II of this book focus on the work of internal coaches. In addition, if you are, or aspire to be, an internal coach, the following points should be considered:

![]() Effective internal coaches need to have the same sensibilities and competencies as external coaches.

Effective internal coaches need to have the same sensibilities and competencies as external coaches.

![]() Well-conceived coaching methods and processes apply equally to external and internal engagements, with several important adjustments to contracting and boundaries.

Well-conceived coaching methods and processes apply equally to external and internal engagements, with several important adjustments to contracting and boundaries.

![]() In keeping with the premise of this book, your particular approach to internal or external coaching can be accommodated within an articulation of your Personal Model.

In keeping with the premise of this book, your particular approach to internal or external coaching can be accommodated within an articulation of your Personal Model.

![]() Internal coaches benefit from organization knowledge but must carefully manage multifaceted relationships with clients, sponsors, and other colleagues.

Internal coaches benefit from organization knowledge but must carefully manage multifaceted relationships with clients, sponsors, and other colleagues.

The growth of internal coaching reflects both increased organizational need for coaching and its perceived value to the organization. As summarized in Chapter 3, individual development planning components have been added to many training, feedback, and leadership development processes. Traditionally, these one-to-one components were delivered by external coaches brought in especially for that purpose. Triggered by logistical and budgetary challenges, these arrangements were examined more closely to reveal that organizations often have internal staff whose interests and skills are similar to external coaches.1

With that realization, organizations have invested in professional development for those internal resources to more directly build their coaching skills. For example, a typical short engagement for internal coaches is to help managers analyze the results of 360-degree feedback to facilitate creating detailed development action plans. The internal coaches delivering those engagements need interpretive skills for the particular assessment instrument used, and more important, they need coaching skills to engage clients in creating a much more actionable and motivating development plan than would have happened on their own.

As internal coaches have proved they are useful and cost-effective, their activities have expanded to cover engagements more traditionally covered by external coaches. These engagements include on-boarding or transition coaching, individual development as follow-up to leadership courses, facilitating manager-client development planning meetings, and development through action learning projects. In organizations where internal coaching has several long-established practitioners, they also may take on three- to six-month coaching assignments usually handled by external coaches. This growing use of internal coaches does not appear to have adversely affected the amount of external coaching being provided; in a sense, both internal and external coaching have benefited from the expansion of coaching. The result is that coaching is available to more managers, deeper in organizations, and as enrichments to larger initiatives. Some organizations have embraced this trend and made it a cornerstone of their organizational identity, labeling it a coaching culture and bringing other developmental initiatives under that umbrella.

While internal coaches feel gratified by their popularity, there are obstacles and challenges to overcome. A frequent one is finding the proper balance between time devoted to coaching and other responsibilities that are part of their jobs. In our experience, internal coaches must carve out coaching time from other roles, such as learning and development (L&D) or organization development (OD) responsibilities. Other internal disciplines also produce internal coaches, such as Human Resource generalists, talent management specialists, and performance management experts. Even line managers or executives get involved by setting aside time to devote to coaching outside their usual chains of command. Providing coach training to managers from many different backgrounds is certainly a challenge, but an even bigger one is securing the time and structure to support their coaching activities. Nothing undermines an internal coaching initiative faster than launching it only to find that none of the coaches have time to actually coach.

Another challenge for internal coaches is that definitions of their roles vary greatly from organization to organization. While in some organizations, internal and external coach roles are almost interchangeable, more often internal coaches are expected to deliver very specialized services reflecting specific organizational needs. For example, an organization may have internal coaches deployed to help salespeople make better presentations, support managers to improve their own coaching skills, or explain and coach about a customized 360-degree feedback tool that is being rolled out. The specificity and diversity of internal coach accountabilities means that training them requires customization. This is especially true if the internal coaches are being drawn from disciplines that do not have a history of one-to-one helping experience, such as leadership development, OD, or talent management.

Other special challenges attached to internal coaching are due to the coworker relationship between coach and client. An internal coach is likely to have continuing contact with a client even after an engagement is over, even if that contact is casual or informal. Internal coaches need to anticipate how to handle unplanned contact with clients and client managers. For example, an internal coach may, as part of her other duties, deliver a training program that a client is attending or facilitate a team-building exercise that includes a past client. In both cases, the coach needs to keep the coaching separate from other activities and to reassure clients about the boundary between the activities.

Informal interactions between internal coaches and a client’s colleagues may also be common, and innocent questions can lead to awkward situations for internal coaches (e.g., “How’s the coaching going?” or “Are you guys still meeting?”). More complex challenges to confidentiality can occur when a coaching client is being considered for a promotion or other change in employment status. Internal coaches need to have both the organizational support and their own backbone to diplomatically sidestep involvement in those discussions that would erode the boundaries of their coaching roles.

Creating and following clear confidentiality guidelines is critical for internal coaches. Just as with external coaching, not everything is confidential, but defining protected information needs to be clear and supported by the organization. If an internal coach is treated as just another HR person, clients may participate in coaching, but they are likely to hold back on making significant revelations out of uncertainty about where that information might end up.

The effectiveness of internal coaches, therefore, cannot be separated from the organizational context in which they work. The accountabilities, goals, and structure of the internal coach role need to be described in detail, in policy guidelines supported by senior executive sponsors. These guidelines need to be included in coach training and communicated to managers and clients before a coaching engagement begins. Unless such guidelines are in place, clients are less likely to trust an internal coach’s assurances about confidentiality.

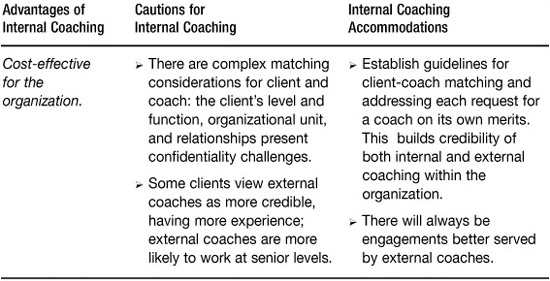

Organizational guidelines for internal coaching can include a definition of the internal coach role, a description of the types of engagements internal coaches will be delivering, and confidentiality definitions in terms of what is protected information and what can be shared (such as development plans). Other details might include how to determine when internal coaching is appropriate, directions and processes for how to access those services, and a coach-client matching process that reduces overlap between their job contexts. In organizations where internal coaching is more ad hoc and initiated by informal request, contracting between coach and client becomes especially important, while still relying on formal support of organizational policy. Figure 20-1 outlines the advantages of internal coaching, and some of the cautions and accommodations that must also be taken in these arrangements.

Internal coaching can be customized to organizational needs but there are several trends in how it is used. First, internal coaches tend to coach at varied levels in the organization, from supervisor to middle manager, and much less likely in executive ranks. As a result, their clients are often earlier in their careers and therefore these coaches may provide more basic managerial skills building. This is not a problem, and it can be very gratifying to help clients at more formative stages, but it does mean that internal coaches need to be well versed in a wide range of managerial topics. Often they will draw from concepts and models used in the organization’s management training programs. In fact, this type of engagement may be formalized when internal coaches do follow-up facilitation after clients attend a management or leadership training program. Similarly, internal coaching engagements are often shorter and more targeted than those of external coaches. They may stipulate a specific number of sessions or a tangible deliverable, such as interpreting results of a 360-degree survey or drafting a development plan.

Second, internal coaches are often involved in engagements that capitalize on their intimate knowledge of the organization, its culture, and its key leaders. This foundation is especially useful in on-boarding new managers who are coming in from outside the organization, but it can also be applied to significant promotions and transitions that internal managers make. One could make a case that the organizational knowledge of an internal coach provides an advantage over an external coach for this transition support work.

Figure 20-1. Internal coach considerations

A third trend is that, once assigned to the role, internal coaches are likely to be asked for counsel, advice, and other guidance outside the boundaries of an actual engagement. These ad hoc consultations may draw on the coach’s skills in listening and offering a different perspective, but strictly speaking, they are not coaching relationships because no process has been agreed upon. Internal coaches use their judgment about whether an ad hoc counseling session is sufficient or if a coaching engagement should be contracted. When there appears to be need and interest in a coaching process, the internal coach would discuss with the potential client a design for a coaching engagement, which may include the usual steps, such as data gathering, sponsor involvement, and development planning. The challenge for internal coaches is to move these interactions either into an actual coaching engagement or refer the colleague to other helping resources. Continuing to meet and talk without contracting next steps in an actual engagement is an inefficient use of both coach and client time. Unfortunately, internal coaches can be in high demand for these counseling conversations, eroding their avaliability for actual contracted coaching. While it is always flattering to be sought out, counseling conversations that do not result in productive next steps are a significant risk to the productivity of internal coaches.

For those readers interested in internal coaching, the considerations presented in this chapter are intended to provide a glimpse into the breadth of the role and its challenges. If you are already operating as an internal coach, apply the contents of the preceding chapters to your internal coach activities and shape a personal model for your coaching that supports your work and is aligned with your organization’s needs. You may discover important ways in which your internal coaching can be more effective and satisfying. You may also discover ways in which your organization needs to better support your internal coaching work. Both your skills and your organization’s policies must be well developed for an internal coaching program to succeed. If you are an external coach, being familiar with the details of the internal coach role will make you a better partner with them.

Part I of this book built the foundation for becoming an exceptional executive coach by introducing the idea of creating a Personal Model based on three inputs and three outputs. Input 1 is your own self-assessment about characteristics you bring to executive coaching. Input 2 prompts you to think about strengths and experiences you bring to working in organizational contexts. Input 3 asks you to consider key topics, practices, and options in executive coaching using the content chapters in Part II of this book. The next chapter begins Part III, which describes how to articulate the three outputs that constitute the more public aspects of your Personal Model: (1) your approach to delivering executive coaching engagements, (2) how you might build your coaching practice, and (3) what your plans are for further developing your coaching skills.

At this point in your learning, you may feel that drafting the outputs of your Personal Model of coaching is a stretch. We acknowledge the challenge of that task, and our students experience similar concerns. At the same time, the sooner you begin to articulate your Personal Model, the better you will be able to both promote your practice and deliver effective coaching services. This is not to pressure or rush you, but instead to help you make tangible progress at whatever level you can manage. Your model will continue to evolve as you accumulate and reflect on new coaching experiences. It would not be desirable or expected for your coaching abilities and approach to remain static. As you celebrate the emergence and continued evolution of your model, you can anchor it in the self-awareness of where you are now, while consciously adjusting as circumstances and your preferences interact.

Chapter 21, highlighting Output 1 of your Personal Model, offers guidance on how to articulate key aspects of your approach to delivering executive coaching services. Chapter 22 focuses on Output 2: how you will secure the coaching work that you seek. Chapter 23 offers suggestions about your continued growth and development as an executive coach; your professional development plan is Output 3. While these three outputs overlap conceptually, each has unique elements for you to consider. Finally, Chapter 24 presents a composite but realistic description of a newer coach on a journey toward learning coaching skills and creating her Personal Model.