12. The Experience of Change

In times of uncertainty, such as those triggered by technological or organizational change, most people have an intense need to know what is happening and how it will affect them. Yet, so often, communication in the form of information, empathy, reassurance, and feedback is in short supply.

Not that no one’s communicating. Griping, for example, is common. So are venting, grousing, and gossiping. The rumor mill runs at full speed. But most of this communication is among those affected by the change. Those who initiated it, in contrast, are silent; or so it seems to those affected. The result is a gap between those who introduce change and those who are on the receiving end.

As always, Scott Adams tells it like it is. In The Dilbert Principle, he notes that people hate change. The reason, he contends, is that change makes us stupider because our relative knowledge decreases every time something changes. “And frankly, if we’re talking about a percentage of the total knowledge in the universe, most of us aren’t that many basis points superior to our furniture to begin with. I hate to wake up in the morning only to find that the intellectual gap between me and my credenza has narrowed.”1 Point well-taken.

1 Scott Adams, The Dilbert Principle: A Cubicle’s-Eye View of Bosses, Meetings, Management Fads & Other Workplace Afflictions (New York: Harper-Business, 1996), p. 198.

Failure to Communicate

During a recent conference at which I gave a presentation on managing change, a member of my audience asked why senior managers are so poor at communicating during times of change. Why, she wanted to know, do they tell us so little, when almost anything would help—even just an acknowledgment of what a stressful time it is for everyone?

Actually, it’s not just senior managers but managers at all levels who communicate inadequately during times of change. These managers include the many who introduce or implement change as well as those who oversee the people affected by it. They may be project managers or team leaders or consultants. Two factors stand out as responsible for creating this Great State of Noncommunication. One is that, despite having experienced nearly nonstop change themselves, many managers simply do not appreciate the jolting impact that change can have on others and fail to recognize even the small steps they can take to help others adjust.

The second factor is that even when those in charge do understand the jarring impact of change, many prefer not to take any action. They avoid communicating because doing so means dealing with those messy “people issues” (such as feelings, for example). As William Bridges notes in Managing Transitions, “Managers are sometimes loathe to talk so openly, even arguing that it will ‘stir up trouble’ to acknowledge people’s feelings.”2 Of course, as Bridges emphasizes, it’s not talking about these reactions that creates the problem.

2 William Bridges, Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change (Reading, Mass.: Perseus Books, 1991), p. 23.

Far too often, in place of communication, management uses a “get” strategy: trying to get people to change. As one vice president put it regarding the resistance of his company’s sales force to use of a complex, new customer-relationship management system, “Our biggest challenge was to get them to change their habits and use it for planning.”

Alas, no one can get anyone else to willingly do something that person doesn’t want to do or doesn’t know how to do. No one can get others to adopt enthusiastically what they fear, resent, or distrust. In a fantasy world, all those affected by a given change would welcome, endorse, and support it, openly and joyfully. Rah, rah, the change is here! But in the real world, change is unsettling. It always has been and it always will be.

The Get Strategy at Work

Inadequate communication was a key contributor to intense negative employee reaction in two companies, the first of which faced technological change and the second, organizational change. The first company embarked on a large-scale, company-wide desktop upgrade. The transition to the current platform a few years earlier had been easy for some employees, but a terrible trauma for others. Although the technology acted temperamentally at times, everyone was used to it by now.

Randy, the project manager of the upgrade implementation team, repeatedly asked his CIO to set the stage for change by issuing a company-wide announcement. Randy reasoned that employees would be more receptive to the upgrade if they knew the reason for it, how they’d benefit from it, when it would take place, and what they could expect as it proceeded. However, the CIO did not provide information to employees. As a result, some employees didn’t become aware of the upgrade until Randy’s team contacted their department to explain and schedule it. Most others learned about it through that most unreliable form of communication, the grapevine.

Employees reacted angrily when technical staff members arrived to “tamper” (their word) with their computers. Anger subsequently turned to outright hostility when employees experienced an unanticipated period of degraded system performance while implementation team members resolved bugs and fine-tuned the network. People fumed, “Why are you pushing this down our throats?”

Called in to meet with several of these employees, I discovered that there had been so little communication that some didn’t even realize that the upgrade was company-wide. They believed it had been designed only for their particular department. The way they experienced it, the change was being done to them, not for them. They were victims of a get strategy.

In the company coping with organizational change, inadequate communication also contributed significantly to employee anger and distress. Describing this experience, Don, a director, bemoaned the dismal morale and escalating staff turnover that followed his company’s merger with a corporate giant. Although a reorganization of his division was certain, and rumors were rampant, months had passed without the release of details by company executives.

Hoping to stop the exodus from his division, Don urged senior management either to talk directly to employees about the upcoming reorganization or, at least, to acknowledge their concerns and let them know when information would be forthcoming. Management ignored his recommendation.

Believing that employees would benefit from an understanding of the psychological nature of how people react to change, Don tried another approach. He offered to give a presentation to his division on the implications of change. Management rejected his offer.

Don was determined not to give up. Trying one last approach, he inserted a slide depicting the experience of change into another presentation he was preparing to give to his staff. When he previewed the presentation for senior managers, they directed him to remove the offending slide before giving the presentation to the troops.

Many months later, senior management rammed a comprehensive reorganization into place without informing, involving, or preparing employees. Morale worsened. The company, once a leader in its field with a sterling reputation as “the place to work,” now became a liability. Turnover led to more turnover, and the company’s severely damaged reputation made staff vacancies difficult to fill.

Why Change Packs a Wallop

In both Randy’s and Don’s companies, management’s view seemed to be, in effect, “If we don’t tell them this is a big change, maybe they won’t notice that their guts are knotting up in response.” Yet these are hardly isolated cases. Perhaps with each wrenching change that they implement, management’s hope is that this time will be different. Maybe, this time, employees will go along meekly and passively, and won’t make a fuss. Maybe, for once, management can just drop the changes into place and tiptoe away. Maybe, people won’t notice that no respect has been shown—either for them or for the fact that big changes always create turmoil.

However, people always notice.

The reason people notice is that significant change is a felt experience. People’s responses to change are much more emotional and visceral than logical and rational. Change efforts trigger a wide variety of reactions—eagerness, enthusiasm, and excitement, as well as fear, trepidation, anxiety, uncertainty, anger, and stress—feelings, in other words, that are both positive and negative.

Change, after all, signifies an end to something. As Bridges notes in Managing Transitions, “When endings take place, people get angry, sad, frightened, depressed, confused. These emotional states can be mistaken for bad morale, but they aren’t. They are the signs of grieving. . . .”3

3 Bridges, op. cit., p. 24.

The importance of the grieving process is acknowledged rarely enough in personal circumstances, but it is given recognition even less frequently in the workplace. Yet, grieving is a response not just to death, but also to other kinds of loss: the loss of a job, a role, a team, a location, a specialty, a valued skill, a way of doing work—the loss, in other words, of a familiar way of life and its attendant safety, certainty, and predictability. People grieve when they lose something that matters to them. Failure to acknowledge people’s need to come to terms with change doesn’t eliminate that need; in fact, it places a greater burden on those who are trying to cope.

What this means is that if you are in a position to introduce change or manage its impact, then what, when, and how you communicate during the course of that change can dramatically influence the success of the effort. Your challenge—and this may signify a change for you—is to communicate with the affected people in a way that acknowledges and respects their reactions, while helping them to accept the change and adjust to it as expeditiously as possible.

The Stages of Response to Change

Jake offered a splendid example of the stages people go through in responding to change. No, Jake isn’t a colleague or an employee; he’s a first-grader, and the son of a friend of mine. Back when he was three years old, his sister Erica was born.

Jake’s parents did their best to prepare him for Erica’s arrival, but when she arrived, Jake totally ignored her. For several days, he kept his distance and avoided any contact with her. He refused to look at her and acted as though she simply wasn’t there.

Gradually, over the next several days, Jake started to acknowledge Erica. First, he gazed at her from a distance; then, he circled around her, moving closer and closer, checking her out. Finally, he dared to approach her, gently poking her hand and softly patting her head. By a week later, the two were great friends. Jake became very fond of Erica, and very protective of her.

What a wonderful illustration of how three-year-olds—and adults—often respond when confronted with change. First, Jake tried to ignore Erica—the intrusion in his life. Then, he slowly acknowledged her existence and took tentative steps toward her. At length, he warmed up to her and accepted her. In the process, he came to realize that she was apparently here to stay, that he wasn’t going to lose his parents’ love and attention, and that maybe she wasn’t so bad, after all.

Of course, I don’t really know what was going through Jake’s head as he attempted to cope with Erica’s arrival. But his reaction to his new sister is analogous to the way adults cope with major change. They may take a different amount of time to reach acceptance, and they may encounter a different amount of distress in the process, but the experience of change is strikingly similar.

Jake was new to the change game, but most of us have had copious experience with it. Businesses change continuously as the world shrinks and becomes increasingly connected. Companies merge, split, realign, and morph in unimaginable ways; organization charts created in the morning are obsolete by lunchtime. Methodologies change, compressing multiyear development cycles into cycles measured in months. Technological change is nonstop and at times teeth-grittingly maddening. And people often fend it off, hoping it’ll go away or at least not affect them. Yet, as pervasive and familiar as change is, the people responsible for introducing it are no more eager to accept it than anyone else—when it affects them. At times, it’s easy to agree with that great philosopher of change, the poet Ogden Nash, who said, “Progress is fine, but it’s gone on long enough.”

Change Models

Numerous models depict the stages of change and the importance of communication in helping people prepare for and adjust to it. The models vary in emphasis and terminology, but each offers insight into how people respond to, experience, and integrate change.

In Managing Transitions, Bridges describes the typical response to change in terms of three phases: ending, the neutral zone, and beginning. Ending is the time during which familiar ways must be given up. The neutral zone is that disconcerting, and sometimes immobilizing, phase between giving up the old way and accepting the new. Bridges warns that the trip through the neutral zone may be quick in some situations and in others, long and slow: “when the change is deep and far-reaching, this time between the old identity and the new can stretch out for months, even years.”4 The third phase, beginning, is what people seek and want, but also find scary once they’re face-to-face with it.

4 Bridges, op. cit., p. 34.

Bridges makes a distinction between change and transition. Change, he states, is situational: the new person or thing, such as the new project, new team, or new manager. Transition, by contrast, is the psychological process people must go through to come to terms with the change. Thus, change is external, but transition is internal.5

5 Ibid., p. 3.

Other change specialists also use stages, or phases, to describe the journey through change. In The 7 Levels of Change, Rolf Smith divides change into distinct levels as a way to develop a strategy for innovation and self-improvement. Smith calls the levels Effectiveness (doing the right things), Efficiency (doing things right), Improving (doing the right things better), Cutting (doing away with things), Copying (doing things other people are doing), Different (doing things no one else is doing), and Impossible (doing things that can’t be done).6

6 Rolf Smith, The 7 Levels of Change: The Guide to Innovation in the World’s Largest Corporations (Arlington, Tex.: The Summit Publishing Group, 1997).

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross describes the stages many people experience in coping with a terminal illness as Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance. In her book On Death and Dying, Kübler-Ross describes the power of communication to help patients come to terms with the prospect of dying.7 Although most organizational change is not of a life-or-death nature (though it may feel like it at the time!), people may experience similar stages as they adjust to it, making KüblerRoss’s advice highly applicable.

7 Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying (New York: Collier Books, 1969).

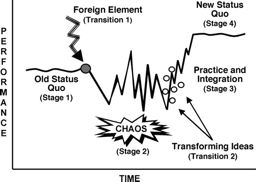

The Satir Change Model

In my work with organizations, I’ve found Virginia Satir’s Change Model extremely valuable in the way it provides a context for understanding the role of communication during change. The Satir model, which depicts the impact of change on performance or productivity, can help you better understand how you respond to change as well as how you can help your organization cope with it.8

8 For an overview, see Virginia Satir et al., The Satir Model: Family Therapy and Beyond (Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books, 1991). For an in-depth treatment of change, see Gerald M. Weinberg, Quality Software Management, Vol. 4: Anticipating Change (New York: Dorset House Publishing, 1997).

Satir herself used initial capital letters in naming the various elements and stages of the Change Model, and these have been retained in the figure below and in the sections that follow. As you read on, consider the impact of the presence or absence of communication during the various stages of change.

Stage 1: Old Status Quo

Old Status Quo is the pre-change stage characterized by the known, the familiar, and the predictable. People in the Old Status Quo stage experience a sense of relative stability. Even when they’re unhappy with the Old Status Quo, many people prefer it to the turmoil and disruption of change. It’s like that old saying, “The enemy we know is better than the enemy we don’t know.” Recall that the employees coping with an upgrade in Randy’s company were comfortable with their current hardware and software, and wanted to keep the familiar system despite its many bugs. Given the choice, most wouldn’t have opted to leave the Old Status Quo. In Don’s company, although many people were disenchanted with the existing organizational structure, they preferred it to the uncertainty of what might come next.

In Teamwork: We Have Met the Enemy and They Are Us, authors Starcevich and Stowell capture the experience of Old Status Quo in noting that most of us have two competing forces motivating our behavior: “Number one is the drive or desire to achieve, succeed, live, experiment, and take appropriate risks and to experience change and variety in our lives. Number two is the drive or desire to be cautious and avoid losses, play it safe, go with the status quo, avoid exposure to risks, and protect our own importance.”9

9 Matt M. Starcevich, and Steven J. Stowell, Teamwork: We Have Met the Enemy and They Are Us (Bartlesville, Okla.: The Center for Management and Organization Effectiveness, 1990), p. 76.

People particularly favor the status quo when they feel stressed; at such times, the known seems more reassuring and trustworthy than the new and different. Thus, when urged to change, many people pull back, tug-of-war-like. Although people who prefer the status quo may be viewed skeptically by those who impose change, this behavior is perfectly normal. To believe otherwise is fruitless. According to the psychiatrist Dr. Pierre Mornell, most people are “allergic” to change and thus you can count on resistance occurring. The reason, he notes, is simply that most people like things the way they are. “And when you start changing direction, people start talking about the good old days, even if they weren’t very good at all.”10

10 Pierre Mornell, “Nothing Endures But Change,” Inc (July 2000), pp. 131–32. Mornell is author of Games Companies Play (Berkeley, Calif.: Ten Speed Press, 2000).

By beginning to communicate about a change before it is implemented, you might be able to help people feel more comfortable with the idea of it so that they can begin to adjust to it.

Stage 2: Chaos

Satir used the term Foreign Element to describe something that upsets the Old Status Quo and throws the system—individuals or groups—into an unsettled state of decreased or impaired performance known as Chaos. Imagine the reaction, for example, when management in one company announced that the entire organization would be moving out-of-state and that employees had a month to decide whether to move with the company or terminate their employment.

This abrupt and unexpected news was a Foreign Element that propelled the entire company into a sudden and intense state of Chaos. Work came to a halt. Gossip and discussion took over. Some people were elated at the opportunity to move; others felt as if they’d been punched in the stomach, severely shocked by the idea of having to either move or find a new job. Reactions were many and varied. Most people became unable to focus on anything other than the implications of the move.

As this situation illustrates, people experience Foreign Elements in different ways. For that reason, I sometimes refer to Foreign Elements as Foreign Elephants, as a lighthearted reminder of the wisdom offered by the poem of the blind men and the elephant. As the poem reveals, each blind man, exploring a different part of the elephant—the ear, trunk, tail, knee, hide—had a different idea of what he was touching.11 The men’s stories were seemingly incompatible, yet each one aptly captured that man’s experience.

11 From the poem “The Blind Men and the Elephant” by John Godfrey Saxe (1816–1887), as quoted in David A. Schmaltz, Coping with Fuzzy Projects: Stories of Utter Ignorance, Theologic Wars, and Unseen Possibilities (Portland, Oreg.: True North pgs, 2000), pp. 5–6.

There are many different types of situations that someone somewhere will experience as a Foreign Element. How many of the situations listed below have you experienced? Have any been Foreign Elements, driving you into Chaos?

• the announcement of an impending layoff (or even just a rumor)

• the arrival of a new CEO or manager

• the arrival or departure of a team member

• yet another reorganization

• the realization that you caused the bug that crashed the system

• the decision to get married or divorced (or remarried or redivorced)

• a call from the Squeaky Wheel

• an unanticipated promotion

• an abrupt change in priorities

• the announcement of a new methodology, technology, or standard

• the news that you’ve won the lottery

• a visit to an unfamiliar country or culture

• an outsourcing decision

• the arrival of consultants

• an unexpected business trip to Hawaii

• a natural disaster

• remodeling your kitchen

• the realization that you overslept and will miss an important meeting

• your most feared error message

• an interruption while you were deep in thought

• the discovery that you’ve lost your keys

• your phone ringing during the night

• the sound of a siren behind your car

As you can see from this list, a Foreign Element can be short-lived or long lasting, expected or unexpected, good news or bad news. It can be seen as positive for some people, negative for others, and neither for still others. It can even be positive for a given person at one point in time and negative at another.

The Chaos stage is a time of uncertainty. While in Chaos, people may have difficulty concentrating, and may become more error-prone, preoccupied, or forgetful. For example, a colleague with whom I had scheduled a phone meeting didn’t call at the agreed-upon time. When I tracked him down, he explained that he had received news that threw him into such turmoil that he simply forgot about our appointment. I could certainly relate to the impact a distraction of that magnitude can have. When I try to write while in Chaos, I make so many typing errors that my spell-checker overheats.

During Chaos, you may feel anger, frustration, fear, confusion, excitement, or a range of other emotions. You may also experience physical symptoms such as a headache, backache, or stomachache. While you can’t always directly observe these emotions or symptoms in others, you can certainly notice them in yourself. Of course, having a stomachache doesn’t necessarily mean you’re in Chaos; the all-you-can-eat pizza shop could somehow be implicated. But if you experience physical distress shortly after being told that you’re now in charge of your least favorite customer, these physical sensations might signal that you’re in Chaos.

You as a Foreign Element

When I ask people to identify examples of Foreign Elements in their work, they generally cite the loss of a job, a major reorganization, new technology, and other such items. However, not all Foreign Elements are “out there.” You can be a Foreign Element for others. Almost certainly, you are at times, by virtue of your role and responsibilities.

The very way that you communicate—how you introduce a new idea, argue your point of view, offer unexpected information, lobby for a new approach, or present bad news—can serve as a Foreign Element that propels recipients of your message into Chaos or causes them to latch onto the Old Status Quo and hold on tight. So if you propose something and people are quick to reject it, refute it, or discount it, they may simply be responding to the introduction of a Foreign Element. However, if you present your information thoughtfully and allow people time to adjust, they may find their way through their Chaos and become receptive to your idea.

It would be absurd to worry excessively about how everyone you interact with will respond to what you say and do; however, an awareness of Foreign Elements and of the Chaos stage may encourage you to find alternative ways of presenting information and ideas so that people are more likely to accept them.

Chaos Is Normal

Chaos is a normal response to change. You can’t prevent people from experiencing it, and you shouldn’t even try. However, what, when and how you communicate with those experiencing Chaos can affect how long and how intensely they experience it. Acknowledging the Foreign Element and the resulting Chaos is an important first step. Talking with employees about their fears and uncertainties can ease their way. Being empathetic if they attempt to revert to the Old Status Quo—that exceedingly common reaction often described as resistance or denial—may provide reassurance.

In the medical context, Kübler-Ross describes denial as “a buffer after unexpected shocking news. . . .”12 In organizations, the news is not always unexpected, but it can still cause employees to respond with denial. As management consultant Steve Smith points out, resistance to a Foreign Element entails “denying its validity, avoiding the issue, or blaming someone for causing the problem.”13 Helping employees understand that these reactions are normal can ease their adjustment to the Foreign Element. At the same time, it may be helpful to make it clear that the change is here to stay and to emphasize the importance of getting past it.

12 Kübler-Ross, op. cit., p. 35.

13 Steven M. Smith, “The Satir Change Model,” Amplifying Your Effectiveness: Collected Essays, eds. Gerald M. Weinberg, James Bach, and Naomi Karten (New York: Dorset House Publishing, 2000), p. 97.

You can’t always tell when people are in Chaos, but one sign you can watch for is a change in their communication patterns. When an even-tempered person becomes a Master Griper or when the department comedian turns serious, these may be signs of an individual in Chaos. Whispering and gossiping are common among people in Chaos. Puzzling interactions, such as those described in Chapter 4, may occur more frequently. Of course, not all mumbling and grumbling signifies a state of Chaos. This behavior, after all, is perfectly normal for some people, or simply a sign of preoccupation or garden-variety stress.

The tricky thing about being in Chaos is that when you’re experiencing it yourself, you don’t always realize it; you can be so tightly in its grip that you lack the presence of mind to stop and say, “I’m in Chaos.” Learning to recognize when you’re experiencing Chaos is a worthy goal because by doing so, you’re more likely to prevent yourself from misspeaking, saying what you don’t mean, making claims you’ll later regret, heaping blame where it doesn’t belong, or taking abrupt action that you’ll later wish you didn’t. Most importantly, you’ll avoid making irreversible decisions that you’d never have made otherwise. By becoming more conscious of what propels you into Chaos, and of how you experience it, you can have more control over your own behavior.

Stage 3: Practice and Integration

In most situations, Chaos doesn’t last forever. It’s a temporary state of tremendous learning that occurs when the old ways no longer apply and the stage is set for a person to try new approaches. With the help of some Transforming Ideas—new ways of looking at the situation—people start to adjust to the changes brought (or wrought) by the Foreign Element. This adjustment stage is called Practice and Integration and it leads to a New Status Quo.

Transforming Ideas can come from many sources, such as quiet reflection, brainstorming, training, research, or talking with others. A woman in one of my workshops described how the Chaos she experienced during a reorganization dissolved when her new manager offered her the opportunity to participate in a new, exciting project. For her, this was a Transforming Idea that enabled her to see new possibilities for herself and therefore to emerge from Chaos and start moving toward a New Status Quo.

Unfortunately, even the very best ideas will not become Transforming Ideas if you’re unaware of them or unwilling to accept them. When in Chaos, many people are quick to dismiss possible Transforming Ideas as ridiculous, unworkable, irrelevant, or deficient in any number of other ways. Therefore, this is an important time to notice people’s communication patterns, especially your own.

To avoid this tendency to dismiss ideas, observe your reaction to the ideas other people offer while you’re in Chaos. If you hear yourself summarily rejecting ideas or finding fault with them, think twice. One of them might prove to be the germ of a Transforming Idea. And if other people are quick to reject your potentially Transforming Ideas because they’re in Chaos, be gently persistent. Sometimes people need time for an idea to settle in before they can accept it.

Practice and Integration is a stage in which communication plays a key role. It’s a time of trying things out, making mistakes, moving forward and slipping back, and gradually becoming more comfortable with the new way. Thus, people who are adjusting to new software, for example, may initially make more mistakes than usual until they become familiar with its features, navigation paths, and menu options. A group emerging from a reorganization may have reduced productivity until group members become accustomed to the new responsibilities, reporting relationships, rules, and procedures.

Just as people sometimes respond to a Foreign Element by reverting to the Old Status Quo, people in Practice and Integration sometimes slip back into the turbulence of Chaos. Some managers don’t appreciate that Practice and Integration is a necessary component of the adjustment to change, and may expect employees to accept the Foreign Element instantly and effortlessly. They may communicate frustration and dissatisfaction as employees take time to adjust to the new way of working.

Enlightened managers, by contrast, understand that this adjustment takes time—and, to the extent feasible, they allow that time. During this period, they interact with employees, listen, and empathize. But they do something more: They help employees understand the ups and downs of Practice and Integration, and they allow employees some leeway to practice new skills and integrate new ways of functioning. Not only do these managers not expect perfection; they help employees understand that unfamiliarity with the new way may temporarily result in an increase in errors and inefficiencies.

Stage 4: New Status Quo

After emerging from Chaos and experiencing the roller-coaster ride of Practice and Integration, an individual or group achieves a New Status Quo. This is a return to relative stability with respect to that particular Foreign Element. Communication at this stage ideally takes the form of reflection, discussion, and evaluation of what’s been learned, because those who learn from their experiences are better equipped to cope with change.

Meta-Change

Over time, and with experience and reflection, individuals and groups can develop expertise in managing the kinds of change that at one time would have provoked intense Chaos. Changing the way you manage and cope with change as a result of this growing expertise is called Meta-Change. By becoming conversant with the change cycle, you can become more sophisticated both in experiencing it yourself and in influencing its impact on others, taking on the role of Change Artist.

The Satir Change Model can help you become a skilled Change Artist in your organization, but you can also use it to manage personal change more effectively. To improve your ability to cope with change personally, consider your own behavior:

1. What behavior do you exhibit when you are in Old Status Quo—especially when you really want to stay there?

2. What kinds of things are Foreign Elements for you? When confronted with a Foreign Element, how do you respond?

3. What is Chaos like for you? What happens to your mental state? your emotional stability? your ability to concentrate?

4. How do your communication patterns change when you’re in Chaos? What might others notice about you?

5. When you’re in Chaos, what do you want from others? How do you let them know?

6. When you’re in Chaos, what might be some sources of Transforming Ideas for you? How can you become more open to those sources?

7. When you’ve reached a New Status Quo, what can you do to learn from the experience so you can minimize the duration and intensity of future Chaos?

8. What can you do differently to improve the way you respond to change?

The questions listed above will help you reflect on how you handle matters of a personal nature but you also can use them to improve your skill as an organizational Change Artist. Review the questions as they pertain to your team, department, division, functional group, or business unit. The following questions can be extremely instructive for a group to contemplate and discuss:

1. What kinds of things are Foreign Elements for your organization? How do you respond, individually and as a group, to these Foreign Elements?

2. What kinds of differences have you observed in how people respond to a given Foreign Element?

3. How does Chaos exhibit itself in your organization? How do people behave? How can you help them when they are in Chaos? How can you let each other know what would be most helpful to you?

4. What changes occur in the ways people communicate with each other while they are in Chaos?

5. While your organization is in Chaos, what are some sources of Transforming Ideas? How can you help others become receptive to these ideas?

6. How can you provide support during Practice and Integration?

7. When your organization has achieved a New Status Quo, how can you help people reflect on what they’ve learned?

8. What can the people in your organization do differently to improve the way they respond to change?

People who possess self-awareness learn what propels them into Chaos and become better at responding to it in the future. By becoming attuned to the experience of Chaos, they become increasingly able to minimize its duration and intensity, and increasingly skilled at managing change.

Chaos As Status Quo

People experience different things as Foreign Elements. They experience Chaos for different lengths of time and at different levels of intensity. They respond to different Transforming Ideas. They have different experiences in Practice and Integration as they achieve a New Status Quo. At any point in time, people are at different points in numerous different change cycles. While the Satir model shows the Foreign Element as creating Chaos, a Transforming Idea can also act as a Foreign Element to create additional Chaos. Sometimes, people in Old Status Quo go through smaller-scale versions of the entire change cycle as they attempt to avoid change in the first place.

All of this is perfectly normal, and quite simply, the way things are. The miracle is that companies are able to achieve so much, given this constant state of flux. (Or could it be that this constant state of flux is precisely what enables them to achieve so much?)

In many companies, nonstop change is the status quo. This state of constant change may be the culture of the organization. Often, what’s seen as constant change is actually a lot of smaller changes that overlap in time and impact. As Bridges points out, “Every new level of change will be termed ‘nonstop’ by people who are having trouble with transition. At the same time, every previous level of change will be called ‘stability.’”14 The tendency people have to view the current “non-stop change” as unique to them or their time in history is a delusion. Constant change has always been the status quo.

14 Bridges, op. cit., pp. 75–76.