7

PLANNING AND CONTROL OF GENERAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE EXPENSES

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, the planning for and control over the area of general and administrative (G&A) expenses are discussed. Typically an amorphous and poorly controlled area, the G&A expense area hides a significant number of expenses that a careful company can take many steps to avoid, or to at least keep from becoming larger. This chapter describes the most common elements of G&A expenses and how to control them, offers a number of pointers on how to reduce them, and finishes with a discussion of the best budgeting methods a controller can use to plan for as well as mitigate the impact of G&A expenses.

By reviewing this chapter, a controller will reach a better understanding of the components of G&A, as well as how to manage them.

COMPONENTS OF G&A EXPENSE

The G&A expense includes costs for a specific set of departments and expenses, which are both described in this section. These departments and expenses are ones that cannot be directly related to production or sales activities and so are segregated in the chart of accounts under a separate account category. This section not only describes the G&A departments, but also the accounts that are most commonly used within those departments.

For a typical company, there are a set of departments that do not relate in any way to production or sales activities, and so by default must be included in the G&A category. These departments address the overall management of the corporation, as well as its financial, computer systems, and legal activities. The departments are:

- The office of the chairman of the board

- The office of the president

- The accounting department

- The management information systems department

- The treasurer's department

- The internal audit department

- The legal department

For each of these departments, there is a common set of expenses, irrespective of the function of each department. These expenses relate to the ongoing salary, operating, and occupancy costs that any functional area must incur in order to do business. The expenses are:

- Salaries and wages

- Fringe benefits

- Travel and entertainment

- Telephones

- Repairs and maintenance

- Rent

- Dues and subscriptions

- Utilities

- Depreciation

- Insurance

- Allocated expenses

- Other expenses

A controller can use the above expenses when setting up any department that falls within the G&A category. However, in addition to these common expenses, there are a large number of additional expenses that do not fall into any clear-cut category, nor can they be listed as being production or sales specific. These expenses, as shown below, cannot be allocated to other departments (or at least not without the use of a very vague basis of allocation), and so must be grouped into the G&A heading:

- Director fees and expenses

- Outside legal fees

- Audit fees

- Corporate expenses (such as registration fees)

- Charitable contributions

- Consultant fees

- Gains or losses on the sale of assets

- Cash discounts

- Provision for doubtful accounts

- Interest expense

- Amortization of bond discount

A controller can use this information to set up a chart of accounts for the G&A expense area.

CONTROL OVER G&A EXPENSES

Some companies get into trouble with investors and lenders, because they have inadequate controls over their G&A costs, which leads to lower profits. It is possible to eliminate these issues by implementing a variety of controls that are useful for keeping G&A costs within an expected range. This section describes a number of controls that serve this purpose.

The potential savings that can be realized through tight control over G&A expenses are usually not as great as those in the manufacturing or sales areas. This is to be expected, because the volume of expenses is far smaller in the G&A area. However, depending on the size of the gross margin, tight control over G&A costs can still lead to a significant change in profits, because it is easier to increase profits by reducing costs than it is to increase profits by increasing sales. In the following example, we show the revenues required to cover the cost of a person with a $50,000 salary:

The table makes it clear that for a low-margin company in particular, it is necessary to increase sales by an enormous amount in order to cover a small additional expense. Thus, it is much easier to increase profits by cutting costs for most companies than it is to increase revenues. Accordingly, the controls noted in this section and the expense reduction ideas listed in the next section are well worth the effort of implementing, even in the G&A area, which does not normally comprise a large percentage of a company's costs.

One of the easier controls to implement is to assign a number of control points to a company's internal audit group for periodic reviews. The internal audit team can observe operations, procedures, and process flows, and compare expenditures to activity levels, thereby acquiring enough information to determine where control points are at their weakest, and require strengthening. Examples of good internal audit targets in the G&A area include:

- Compare process efficiencies to those of best-practice companies and recommend changes based on this review.

- Confirm the results of consulting engagements, and construct cost-benefit analyses for them to determine which consultants are creating the largest payoff.

- Review the bad debt expense to see if there is an unusual number of write-offs, and recommend changes to the credit granting policy based on this review.

- Verify that all dues and subscriptions have been properly approved.

- Verify that all paychecks cut are meant for current employees.

- Verify that assets are categorized in the correct depreciation pools.

- Verify that cellular phone usage is for strictly company business.

- Verify that charitable contributions are approved in advance.

- Verify that insurance expenses are competitive with market rates.

- Verify that legal expenses are at market rates.

- Verify that office equipment is not incurring excessive repair costs.

- Verify that phone expenses are in line with market rates.

- Verify that scheduled rent changes have been paid.

- Verify that there are proper deductions from paychecks for benefits.

- Verify that there is approved backup for current employee pay rates.

- Verify that travel and entertainment expenses are approved.

- Verify that travel and entertainment expenses are in accordance with company policy.

Besides the internal audit team, another good control point is the budget. A controller should always hand out a comparison of actual expenses to the budget after each month has been closed, so that all managers in the G&A area can gauge their performance against expectations. In addition, there should be a report that lists the amount of money left in each manager's budget, so that there is no reason for anyone to demand extra funds towards the end of the fiscal year. The strongest control in this area is to have the purchasing system automatically check on remaining budgeted funds, so that a purchase order will be rejected if there are not sufficient funds on hand through the accounting period. Thus, a budget can be used in several ways to create tight control over G&A costs.

Another control method is to divide up all G&A costs by responsibility area and tie employee bonuses and pay rate changes to those costs. For example, the building manager can be made directly responsible for all occupancy costs, and will only receive a pay raise by reducing the overall occupancy costs by a preset percentage. When using this method, it is best to set up a range of compensation goals, so that an employee can still go after a lesser target, even when it becomes apparent that the main cost goal is not reachable. To expand on the previous example, there can be a large pay raise if occupancy costs are reduced by 5 percent, a modest pay raise if the reduction is only 2 percent, and a very minor pay raise if the person can do nothing but maintain occupancy costs at their current level. By using this multitiered compensation system that is tied to direct responsibility for G&A costs, there is a much greater chance that managers will pay close attention to those G&A costs that are assigned to them.

One problem with dividing up G&A costs by responsibility area is to find a reasonable method for doing so, since it is quite possible to erroneously charge G&A costs to the wrong person, which may lead to behavior that does not match company objectives. Fortunately, there are several allocation methods available that allow one to assign costs to facilitate planning and control, by responsibility center, and to cost pools, in case a company is using activity-based costing. The preferred method of allocating G&A costs is based on a hierarchy of alternatives, which are listed in descending order of usability:

- Allocated based on the amount of resources consumed by the cost center that is receiving the service. For example, if a division is using the central accounting staff to create invoices for it, costs should be allocated to that division based on the cost of creating an invoice, multiplied by the total number created for that division.

- Allocated based on the relative amount caused by the various cost centers. This method is less precise, because there is not a direct relationship between the activity and the cost, only a presumed one. For example, medical costs can be allocated to a department based on the number of people in a department; we assume that the people in that department take up a proportionate share of medical costs, even though this may not be the case. Other examples are allocating costs based on the material cost of an item (such as material handling costs), based on square footage (such as physical facility costs), or based on energy consumption (such as the rated horsepower of a machine). Though not as accurate as the first method, this approach allows one to allocate most costs on a fairly rational basis.

- Allocated based on the overall activity of a cost center. This method is the least precise, because it is only based on a general level of activity, which may have no bearing on a cost center's actual expense consumption. An example of an overall activity measure is the three-factor Massachusetts Formula, which is a simple average of a cost center's payroll, revenue, and assets as a proportion of the same amounts for all cost centers. This approach essentially charges costs to those areas that have the greatest ability to pay for services, irrespective of whether or not they are using them.

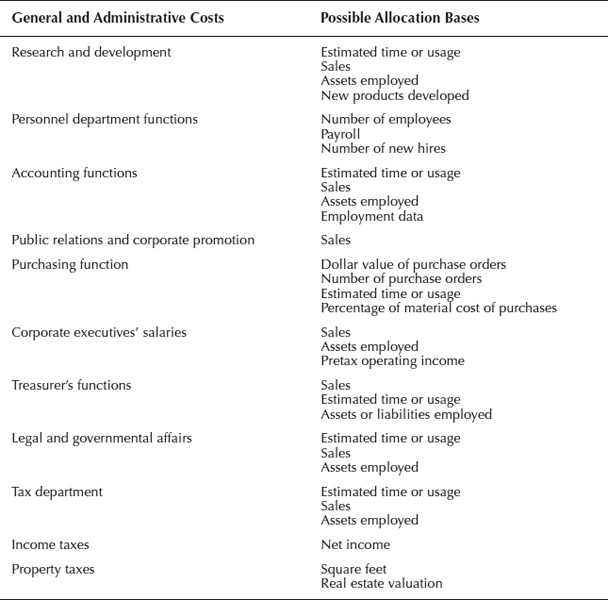

Exhibit 7.1 shows a number of ways to allocate costs. The exhibit covers activities in a variety of areas, and notes allocation methods that are based on one or more of the preceding allocation methods. The exact allocation method chosen will depend on an individual company's circumstances.

No matter which of these allocation methods is used, one should keep in mind the end result—attaining a greater degree of control over costs. If the allocation method is excessively time consuming or expensive to implement, one must factor this issue into the assumed savings from having a greater degree of control over G&A costs and make a determination regarding the cost effectiveness of the allocation method.

When allocating costs, one should also consider the impact on the recipient of the allocation. It is best to allocate only those costs over which a recipient has direct control, since the recipient can take direct action to control the cost. If a cost is allocated that the recipient can do nothing about, there is much less reason to make the allocation. For example, computer programming costs can be charged to a cost center for the exact amount of the time needed to develop a requested report—if the manager of that cost center does not want to incur the cost, then he or she should not request that any reports be developed. Alternatively, if senior management wants to encourage the use of certain internal resources, such as legal, accounting, or computer services, it can reduce the activity costs of these functions to below-market rates, which will encourage managers to use them. Either approach involves cost allocations that managers can directly impact by choosing to consume or not consume G&A services.

EXHIBIT 7.1 ALLOCATION BASES FOR G&A COSTS

Another way to control G&A costs is to create standards for each activity performed, which can then be used to compare against actual performance, in the same way that labor standards have been used in the manufacturing arena for decades. By tracking performance based on these standards and modifying systems to match or beat the standards, a controller can achieve a high performance G&A function. To create standards for this purpose, use the following steps:

- Observe work tasks. Carefully note the steps and duration of a task. This step is fundamental in securing the necessary overall understanding of the problem and in picking those areas of activity that lend themselves to standardization. For example, it will not be possible to create a standard if there are an excessive number of variations that are commonly part of a work routine. In addition, the preliminary review will spot any obviously major weaknesses in a routine.

- Select tasks to be standardized. The preliminary review will reveal those routines that are the best candidates for standard creation. The two main criteria for this will be that a routine has enough volume to justify the work of setting a standard, and that a routine does not include so much variation that it is impossible to create a reliable standard. These two criteria will quickly reduce the number of standards to a modest percentage of the total number of routines used in the G&A area.

- Determine the unit of work. There must be a measurement base upon which to set a work standard. Examples of units of work follow:

Function Unit of Standard Measurement Billing Number of invoice lines Check writing Number of checks written Customer statements Number of statements Filing Number of pieces filed Mail handling Number of pieces handled Order handling Number of orders handled Order writing Number of order lines Posting Number of postings Typing Number of lines typed - Determine the best way to set each standard. Various kinds of time and motion studies can be applied to each work routine, depending on the nature of the work.

- Test each standard. After a standard has been set, it should be tested with varying workloads to determine whether it is a reasonable standard. Keep in mind that a standard is much less effective if an employee has many tasks to perform, since it is often necessary to jump repeatedly between tasks. In these cases, it may not even be practical to install standards for any but the most high-volume routines.

- Apply the standard. This step involves explaining the standard to each employee on whom it will be used, as well as to supervisors. In addition, one should set up a reporting system for tracking this information, and a feedback loop that tells employees how they are doing against the standard.

- Audit the standard. There should be a regular schedule of reviews for each standard, so that there is not a problem with a standard becoming so out of date that it no longer reflects the current level of efficiency of each routine. In addition to the scheduled reviews, there should also be a review every time there are major changes to a routine, possibly due to the implementation of a best practice, which would invalidate a standard.

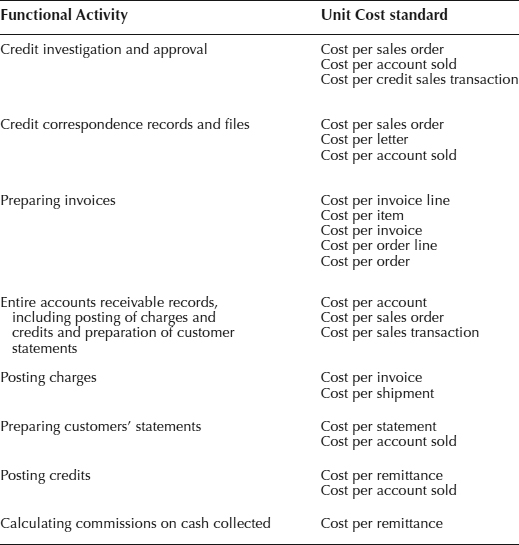

In addition to performance standards, unit cost standards can be applied to measure an individual function or overall activity. Thus, applying cost standards to credit and collection functions may involve these functions and units of measurement, depending on the extent of mechanization. (See Exhibit 7.2.)

By applying the standard creation methods noted in this section to G&A activities, it is possible to exercise additional control over the more repetitive tasks within the G&A area.

There are a number of controls that a controller can implement to ensure that G&A expenses stay within an expected range. These controls include periodic reviews by the internal audit department, both manual and automated comparisons of budgeted to actual costs, and the development of unit cost standards. By using a selection of these controls, there is much less chance that there will be any significant variations from expected G&A costs.

EXHIBIT 7.2 APPLYING COST STANDARDS TO CREDIT AND COLLECTION FUNCTIONS

REDUCING G&A EXPENSES

Unfortunately, many controllers feel that the G&A expense is a fixed one, and consequently make little effort to reduce it. Although it is true that there are better methodologies for cost reduction in other functional areas of a company, there are still a considerable number of cost reduction techniques that a controller can implement to reduce G&A costs.

The principle issue to remember when trying to cut costs is that one must attack the underlying assumptions that are protecting G&A expenses, rather than trying to make incremental adjustments to those expenses by using greater efficiencies. In many cases, the only way to bring about massive reductions in G&A costs is to completely eliminate some categories of costs. Why go to this extreme? Because G&A costs do not directly contribute to revenue gains or production efficiencies—they are dead weight—and must be constantly reviewed to ensure that they are kept at an absolute minimum, even if the company as a whole is growing at a great rate.

If a company consists of a central headquarters that oversees the functions of a large number of facilities or subsidiaries, there may be a chance to reduce a very large proportion of the existing G&A expense. This reduction can be achieved by altering the management concept of the headquarters group. By altering this key underlying assumption of how to manage a company, it becomes possible to decentralize and push management functions down into the various facilities or subsidiaries, thereby vastly reducing the need for most of the staff in the headquarters facility. This approach is the single most effective way to reduce G&A costs.

Another general cost reduction concept that applies to nearly all parts of the G&A area is the use of outsourcing. This approach questions the underlying assumption that there is a need for an in-house staff to handle every G&A function. For example, a legal staff can be eliminated in favor of using an outside law firm that handles company legal issues. Though the hourly cost of using this approach may be quite high, it can be cheaper over time, for several reasons. First, the in-house staff tends to find work for itself to do, even though that work may not be entirely necessary. Second, there tends to be a greater emphasis on cost reduction when an expensive outside service is used that charges by the hour (or minute), especially when that cost can be traced back and charged to a specific department. Finally, the cost becomes a variable one when the fixed cost of the in-house staff is eliminated in favor of one that is incurred only when needed. Thus, outsourcing is a valid approach for reducing G&A costs.

Besides the general cost reduction methods just noted, there are a variety of specific cost areas that deserve the attention of the controller. The following list notes a variety of techniques that can be used to reduce costs in specific G&A areas:

- Audit expense. Most companies hire a group of outside auditors to review the year-end financial statements. The cost of this audit can be substantial, especially if company operations are widely separated or if the accounting records are not well organized. A controller can succeed in reducing the audit expense by changing to a different type of review. Instead of a full audit, it may be possible to have the auditors conduct a compilation or review, both of which are less expensive. However, these alternatives do not provide for as complete a review of the accounting records, so the switch may meet with resistance from lenders, who rely on the results of the audit to determine the risk of continued lending to a company. Another way to reduce expenses in this area is to volunteer the services of the accounting staff in assisting the external auditors. Though these services will be limited to a supporting role, it will reduce the hours charged to the company by the auditors, which will reduce the overall cost of the audit.

- Bad debt expense. A controller can have some of the accounting or internal auditing employees assist the external auditors during the annual audit of a company's financial records. This can reduce the size of the audit fee, since the hourly rate charged by an external auditor is typically several times the hourly rate paid to employees. This approach has its limitations, since there are only so many tasks that an audit team will allow the in-house staff to take over.

- Charitable contributions. This is a rare area for a company to exercise much cost control over, perhaps because there are so many worthy nonprofit organizations that are in need of a company's cash. However, it is reasonable to target a company's charitable giving to specific organizations that best meet its charitable giving goals. By creating an approved giving list at the beginning of each year, a company can avoid giving to organizations that are not on the approved list, thereby bringing about a reduction in the cost of contributions while still achieving the company's overall charitable giving goal.

- Equipment lease expense. Many companies purchase all of their office equipment at wide intervals, and obtain leases to pay for them without much thought for the terms of those leases, which tend to be high. A better approach is to consolidate all of the leases into a single master lease, which a controller can then shop to a variety of lenders to obtain the best possible lease rate.

- Forms expense. Some companies have such a large expense for the printing of a multitude of forms that they even have a separate line item in the budget to track it. This is a particular problem for paper-intensive companies such as those in the insurance industry. A controller can reduce this expense by conducting a complete review of all forms to see which ones are no longer necessary. Another option is to combine forms, so that the functions performed by many forms can now be completed with just a few. It may also be possible to convert paper-based forms to on-line ones, so that there is no printing expense at all. Another possibility is to reduce the number of copies of each form, so that they are routed to fewer people within a company. This has the double benefit of reducing the paper cost while also reducing the volume of paper working its way through a company. All of these steps can significantly reduce a company's forms expense.

- Interest expense. Interest expense is generally classified with G&A expenses; however, the underlying reason for the expense lies elsewhere. Interest expense is caused by debt, and debt is needed, to a large extent, to fund working capital requirements, such as accounts receivable and inventory. By paying close attention to accounts receivable collections and inventory usage, a controller can have a major impact on the amount of cash being funded through debt, which will shrink the amount of interest expense.

- Officer salaries. An exceedingly large part of the G&A expense is officer salaries. It is quite unlikely that a controller can persuade more senior executives to cut their pay, but it may be possible to influence the decision to alter the components of officer salaries, so that a larger proportion of it is tied to profitability or other similar performance-related targets. By inserting a large variable component into the officer salary expense, it is possible to reduce the expense substantially during periods when performance goals are not reached.

- Reproduction expense. The cost of copying documents is astronomical at many companies. There are several ways to reduce it. One way is to focus on the expense of the copiers used. For most employees, a very simple copier model that replicates and sorts is all that is needed, with only a small minority of the staff needing a copier with more advanced functions. Accordingly, a controller can replace expensive copiers with simpler ones, while still retaining a few complicated machines for the most complex printing jobs. Another option is to standardize on a single type of copier, which allows a company to stock a limited number of service and replacement parts for all of them, rather than a wide range of parts for a wide range of copiers. In addition, it may be possible to outsource the larger print jobs to a supplier, allowing a controller to specifically trace the billings for these jobs to the person requesting the work, which brings home to management the exact cost of reproduction, which would otherwise be buried in the overall cost of G&A expenses.

- Storage space. A great deal of the office space allocated to the G&A function is filled with documents. A controller can reduce the amount of prime office space devoted to record storage by reviewing the documents and consigning all but the most current ones to cheaper off-site storage facilities. Also, a good archiving policy will allow a company to throw away records that have reached the limit of their usefulness, both from a legal and operational perspective, which also reduces the amount of storage space. Finally, some or all documents can be scanned into a database for retrieval through the computer system, which not only eliminates storage space, but also reduces the time that would otherwise be spent finding records and returning them to storage.

- Telephone expense. There are a plethora of options that allow a controller to drop telephone expenses down to just a few pennies a minute, even for long-distance calls. To achieve such a large cost reduction, a controller should first review all existing phone invoices to determine the number and cost of extra phone services, and then determine the need for those services. Next, one must determine the number of phone lines used, as well as the need for special phone lines that carry extra charges (usually because they offer extra bandwidth), such as ISDN or T1 lines. Finally, after adjusting the types of services and number of lines, a controller can review the prices offered by different carriers to determine the lowest possible per-minute charges. With Internet phone service now becoming available, the possibility of acquiring phone service for under five cents a minute is in sight. Since some companies have extremely complex phone systems, it may be best to hire a company that specializes in reviewing phone systems, since they can provide a more knowledgeable view of phone options.

Besides the general and specific cost reduction options that have already been noted in this section, there is also the cost contained in the efficiencies of the tasks performed under the umbrella of G&A expenses. By paying close attention to the efficiency of these processes, a controller can wring out additional cost savings. The methodology to use when improving G&A efficiencies is a simple one. Essentially, one must clear out any unnecessary tasks or paperwork that are cluttering the work area, thereby allowing a clearer view of the underlying processes that require fine tuning. One can then review and eliminate a number of types of duplication, and then focus on automation, reduced cycle times, training, and benchmarking to achieve extremely high levels of efficiency. The specific efficiency improvement steps are:

- Clean up the area. Though a seemingly simple task, this is one that many people never get past. By reviewing all documents in an area and archiving anything more than a few months old, one can quickly reduce the volume of work that appeared to be part of the backlog of a job. If possible, as much of this old material as possible should be thrown out, in order to save on archiving costs, but just getting it out of the primary work area is the main target, not shifting it into a dumpster.

- Eliminate duplicate documents. Once the old paperwork has been eliminated or moved, it is time to compare the remaining documents to determine whether there are any duplicates. If so, it is only necessary to keep one copy. The remainder can be thrown out or archived.

- Eliminate duplicate tasks. It is entirely possible that some information is being prepared by more than one person in the same organization. The best way to spot this problem is to bring people together into teams, and review each other's work. It can be very helpful to include people from widely separated parts of a company, since they will have a better knowledge of any data being prepared in their areas that is already being prepared elsewhere (as they will find out by interacting with the review teams).

- Eliminate reports. Now it is time to shrink the work being performed. A classic case of work reduction is to make a list of all the reports generated, and then walk them through the organization to see if they are really needed anymore. In addition, one can review the elements of a report to see if some items can be eliminated that require large amounts of data collection or analysis. Thus, either a report can be eliminated, or some of the information in it.

- Eliminate multiple approvals. A review team can plot out the flow of documents through an organization, which frequently reveals a large number of unnecessary and redundant approvals that are lengthening the time required to complete processes. By identifying only the most crucial approvals and eliminating all others, the time wasted while waiting for all the other approvals can be removed from processes, dramatically shrinking cycle times.

- Use automation. There are many types of automation that can be used to reduce the workload of people in the G&A area. Some are common, such as the automated voice response system that replaces the receptionist, while others, such as document imaging systems, are less well known but also offer significant monetary savings. When using automation, it is important to first review the capital and ongoing costs of the new systems in comparison to the existing costs, to ensure that there is a sufficient pay back to make the projects worth the time and effort of installation and maintenance.

- Provide training. Too many companies make the mistake of assuming that their staffs need no extra training, and then even if they do, the company that foots the bill will not see an adequate return on its training dollars. To avoid these problems, a company should carefully compile a set of training classes for each job title, so that each person receives extremely job-specific information, rather than generic information that does not give a recipient much practical knowledge. By focusing on targeted training, it is much easier to improve the quality of employees, who return the favor by applying their new knowledge to improve the efficiency of their jobs.

- Rearrange the workspace. Most employees do not work in areas that allow them to complete the majority of their work while sitting in one place. Instead, they must walk to distant filing cabinets, copiers, or fax machines. By altering the office layout to reduce the amount of movement, a controller can achieve a significant productivity improvement. Sometimes, the best approach is to multiply the amount of inexpensive office equipment. For example, if someone is a heavy user of a copier, typewriter, or fax machine, then procure an inexpensive variety of each one of these office tools and set it up right next to that employee; some very low-end copiers are now so cheap that a controller can give one to every employee, if necessary.

- Staff for low volume. Some G&A functions have large swings in the volume of transactions they process, especially if the business is a seasonal one. If so, it may be possible to maintain a small core staff that handles a modest volume of work and then bring in temporary workers to cover the workload when the volume of work rises. This approach reduces the overall labor cost, although the temporary staff will be less efficient than the permanent employees, who are more experienced.

- Benchmark G&A. Once all of the preceding tasks have been completed, management should not become complacent and think that it has a world-class G&A function. Instead, this is an ideal time to benchmark a company's operations against those of companies who have become acknowledged masters in certain functional areas. Another way to collect benchmarking information is to use recommendations by the company's auditors, who see the operations of many companies, and can recommend practices used by other organizations. By seeing how much better these companies handle their G&A areas, management is spurred on to loop back through the preceding tasks and find better and better ways to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the function.

- Cross-train the staff. Once a company has gone through several of the steps in this process, it will find that there are fewer people in the G&A area—so few in some areas that there may be only one person left with a knowledge of how a process works. To avoid the danger of losing this information with a departing employee, it now becomes important to cross-train employees in multiple functional areas. Also, this allows for further reductions, so that one employee can handle multiple functions.

There are a multitude of possibilities for reducing G&A costs. These options fall into three main categories. One is to question the underlying assumptions for incurring broad categories of costs. For example, there may be no need for any headquarters staff if the management philosophy is changed to emphasize control at a local level, rather than from headquarters. The next category is changes that target specific expenses, of which numerous examples were cited. Finally, one can focus on the overall efficiency of transactions, for which a variety of steps were noted; by following these steps, a controller can reduce the cycle time and cost of many G&A operations. Taken together, the steps noted in this section can have a dramatic impact on G&A expenses.

BUDGETING G&A EXPENSES

In most companies, G&A expense is not budgeted as a percentage of sales, since it is relatively fixed and does not vary with sales. However, many G&A functions can be viewed as step costs. For example, accounts receivable volume will decline as sales drop; if there is a signified reduction in sales volume, then the budget for a receivables position would be eliminated. On the other hand, there are many fixed costs. For example, director expenses are fixed, since the same number of board meetings will occur, no matter how much sales volume may vary.

However, there are many discretionary costs. Withholding expenditures on discretionary items can have a marked impact on profits, so a separate analysis of discretionary G&A costs should be made available to management, especially if profitability is expected to be a problem.

Areas where costs may verge on variable costs instead of step costs are the salaries of the payroll, cost accounting, cashier's, and internal audit departments.

The budget preparation procedure for G&A varies somewhat from the procedure used for production, since there is no budget for purchased materials, inventory, cost of goods sold, or direct labor. A typical G&A budget preparation procedure includes:

- The controller or budget director makes available to each functional executive and/or department head, in either worksheet form or computer accessible data:

- (a) Actual year-to-date expenses and head count

- (b) Assumptions to be used for budgetary purposes: percent of pay raise, fringe benefit cost percent, inflation rate, generally acceptable rate of expense increase, etc.

- (c) Any relevant information on the business level, economic conditions, etc.

- (d) Instructions on preparing the planning budget

- The department head completes the budget proposal and sends it to his supervisor for approval, who then forwards it to the budget director.

- The individual department budget requests are reviewed by the budget director, checked for reasonableness and completeness, and, when acceptable, summarized for the central office by responsibility.

When the aggregate G&A budget is accepted, it becomes part of the annual business plan.

- Monthly, the department expenses—actual and budget—are compared by the department head, who takes corrective action where appropriate. This report shows any significant over- or underrun. Budget performance could also be reported on a graphic basis. This report also explains significant overruns. The monthly trend of performance, by group and in total, could be displayed in vertical bar chart or line graph. The entire group performance could be summarized as to budget and actual expense by natural expense category (salaries and wages, travel and entertainment, etc.).