8

PLANNING AND CONTROL OF CASH AND SHORT-TERM INVESTMENTS

INTRODUCTION

Most business executives have long been aware of the need for cash. Supplier bills must be paid by cash. Payrolls must be met with cash. The ability of an entity to generate adequate cash has assumed more importance. Witness the attention given cash flow in leveraged buyouts (LBOs) or other proposed mergers or acquisitions. Or consider the standard issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) for cash flow reporting—FAS No. 95, Statement of Cash Flows.

In any event, sound cash management is a basic financial function. While it is usually the responsibility of the senior financial officer, the controller has an important role to play. This chapter reviews the phases that the controller either handles or has a direct interest in:

- Cash planning, with emphasis on the annual plan

- Some aspects of cash control, including internal control

- Limited comments on temporary investments, given their close relationship to cash

OBJECTIVES OF CASH PLANNING AND CONTROL

Cash is a particularly vulnerable asset because, without proper controls, it is easily concealed and readily negotiable. But it is something every business needs. From an overall viewpoint, cash management would have these six objectives:

- Provision of adequate cash for operations—both short and long term

- Effective utilization of company funds at all times

- Establishment of accountability for cash receipts and provision of adequate safeguards until the funds are placed in the company depository

- Establishment of controls to ensure that disbursements are made only for approved and legitimate purposes

- Maintenance of adequate bank balances, where appropriate, to support proper commercial bank relations

- Maintenance of adequate cash records

DUTIES OF THE CONTROLLER VERSUS THE TREASURER

With respect to cash management, a cooperative relationship should exist between the controller and treasurer. Duties and responsibilities will vary, depending on the type and size of the business firm. Under ordinary circumstances, the treasury staff has custody of cash funds and administers the bank accounts. Usually, it is the treasurer who is responsible for maintaining good relations with banks and other investors, providing the timely interest and principal payments on borrowed debt, and investing the excess cash. The treasurer usually would have primary responsibility for cash receipts and disbursement procedures.

The controller may have these responsibilities in companies large enough for separate treasury and controllership functions:

- Development of some, or all, of the cash forecasts

- Review of the internal control system with respect to both receipts and disbursements to assure its adequacy and effectiveness

- Reconciliation of bank accounts—as part of a sound internal control system (and not to be done by members of the treasurer's department who have access to funds or by accounting personnel who record the transactions)

- As may be deemed appropriate, preparation of selected cash reports

THE CASH FORECAST

Purposes of Cash Forecasting

A cash forecast, or cash plan, or cash budget, is a projection of the anticipated cash receipts and disbursements and the resulting cash balance within a specified period. This is a necessary function in any well-managed plan of cash administration.

The operation of any business must be planned within the limits of available funds, and, conversely, the necessary funds must be provided to carry out the planned business operations.

In these days of increasing sales and earnings, and taxes, business management is rediscovering that profits are not the same as cash in the bank. The company may show a small profit, or even a loss, and have a very sizable cash balance. Particularly in those industries requiring heavy capital investment, the cash generation by the operations, the “cash flow,” may be very heavy and yet result in mediocre profits. For reasons such as these, cash forecasting is being recognized as a vital management function.

The basic purpose behind the preparation of the cash budget is to plan so that the business will have the necessary cash—whether from the short-term or long-term viewpoint. Further, when excess cash is to be available, budget preparation offers a means of anticipating an opportunity for effective utilization. Aside from these general purposes, some specific uses to which a cash budget may be put are:

- To point out peaks or seasonal fluctuations in business activity that necessitate larger investments in inventories and receivables

- To indicate the time and extent of funds needed to meet maturing obligations, tax payments, and dividend or interest payments

- To assist in planning for growth, including the required funds for plant expansion and working capital

- To indicate well in advance of needs the extent and duration of funds required from outside sources and thus permit the securing of more advantageous loans

- To assist in securing credit from banks and improve the general credit position of the business

- To determine the extent and probable duration of funds available for investment

- To plan the reduction of bonded indebtedness or other loans

- To coordinate the financial needs of the subsidiaries and divisions of the company

- To permit the company to take advantage of cash discounts and forward purchasing, thereby increasing its earnings

Cash Forecasting Methods

At least two methods are in widespread use for developing a cash forecast. Although the end product is the estimated cash balance, the methods differ chiefly in terms of the starting point of the forecast and the detail made available. These two techniques are described as:

- Direct estimate of cash receipts and disbursements. This is a detailed forecast of each cost element or function involving cash. It is essentially a projection of the cash records. Such a method is the one most commonly used in business and is quite essential to giving a complete picture of the swings or gyrations in both receipts and disbursements. It is particularly applicable to those concerns subject to wide variations in activity. Moreover, it is very useful for controlling cash flow by comparing actual and forecasted performance. A cash forecast prepared on this basis is shown in Exhibit 8.1. The individual line items will depend on what items are significant, and/or on those in which the management is especially interested—presuming the actual data are also readily available from the cash records for comparing budget with actual results. The cash inflows and outflows from operations are shown; thus, management can easily see the cash flow generated by operations, and the cash flows from investing activities and financing activities are readily determinable. If changes in the annual plan (e.g., sales) cause adjustments in cash flow, the use of the computer for this detailed cash planning makes such modifications rather easy.

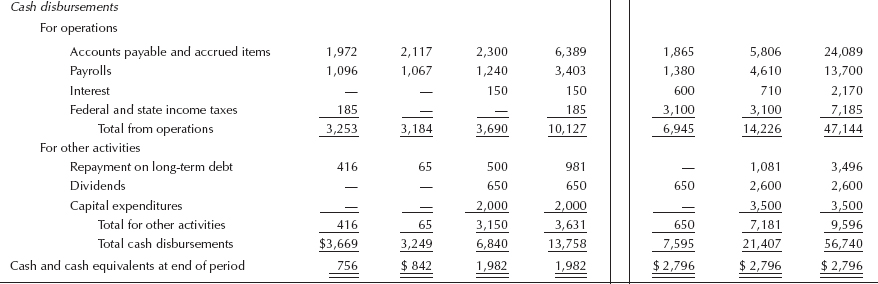

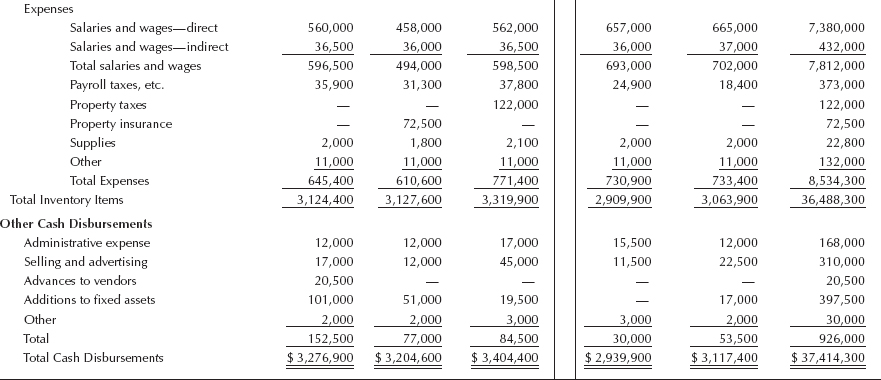

- Adjusted net income (or indirect or reconciliation) method. As the name implies, the starting point for this procedure is the estimated income and expense statement. This projected net income is adjusted for all noncash transactions to arrive at the cash income or loss and is further adjusted for cash transactions that arise because of non-operating balance sheet changes. A worksheet showing the general method is illustrated in Exhibit 8.2.

Because net income is used, the true extent of the gross cash receipts or disbursements is not known. Where a company must work on rather close cash margins, this method probably will not meet the needs. It is applicable chiefly where sales volume is relatively stable and the out-of-pocket costs are fairly constant in relation to sales.

This format identifies the cash flows according to source—from operating activities, from investing activities, or from financing activities. This segregation is that suggested by the FASB for inclusion in published financial statements. It may or may not be used for internal planning purposes. If this style is utilized, it permits management to readily see the relative size of each estimated cash flow source approximately as it will appear in the annual report to shareholders.

EXHIBIT 8.1 STATEMENT OF ESTIMATED CASH RECEIPTS AND DISBURSEMENT

EXHIBIT 8.2 STATEMENT OF ESTIMATED CASH FLOWS (INDIRECT METHOD)

Estimating Cash Receipts

The sources of cash receipts for the typical industrial or commercial firm are well known: collections on account, cash sales, royalties, rent, dividends, sale of capital items, sale of investments, and new financing. These items can be predicted with reasonable accuracy. Usually, the most important recurring sources are collections on account and cash sales. Experience and a knowledge of trends will indicate what share of total sales probably will be for cash. From the sales forecast, then, the total cash sales value can be determined. In a somewhat similar fashion, information can be gleaned from the records to enable the controller to make a careful estimate of collections.

Once the experience has been analyzed, the results can be adjusted for trends and applied to the credit sales portrayed in the sales forecast.

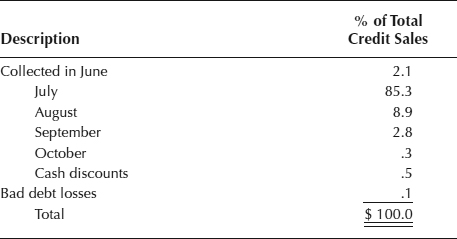

An example illustrates the technique. Assume that an analysis of collection experience for June sales revealed the following collection data:

If next year's sales in June could be expected to fall into the same pattern, then application of the percentages to estimated June credit sales would determine the probable monthly distribution of collections. The same analysis applied to each month of the year would result in a reasonably reliable basis for collection forecasting. The worksheet (June column) for cash collections might look somewhat as:

Anticipated discounts must be calculated, since they enter into the profit forecast.

These experience factors must be modified, not only by trends developed over a period of time but also by the estimate of general business conditions as reflected in collections, as well as contemplated changes in terms of sale or other credit policies. Refinements in the approach can be made if experience varies widely between geographical territories, types of customers, or channels of distribution. The analysis of collections need not be made every month; it is sufficient if the distribution is checked occasionally.

Exhibit 8.3 is an example of a typical statement of estimated cash receipts by customer type. In this instance receipts from particular contracts are set out in addition to the usual collections from customer sales.

Estimating Cash Disbursements

If a complete operating budget is available, the controller should have little difficulty assembling the data into an estimate of cash disbursements. The usual cash disbursements in the typical industrial or commercial firm consist of salaried and hourly payrolls, materials, taxes, dividends, traveling expense, other operating expenses, interest, purchase of equipment, and retirement of stock.

From the labor budget, the manufacturing expense budget, and the commercial expense budget, the total anticipated expense for salaries and wages can be secured. Once this figure is available, the period of cash disbursement can be determined easily, for payrolls must be met on certain dates, closely following the time when earned. Reference to a calendar will establish the pay dates. Separate consideration should be given to the tax deductions from the gross pay, since these are not payable at the same time the net payroll is disbursed—unless special bank accounts are established for the tax deductions.

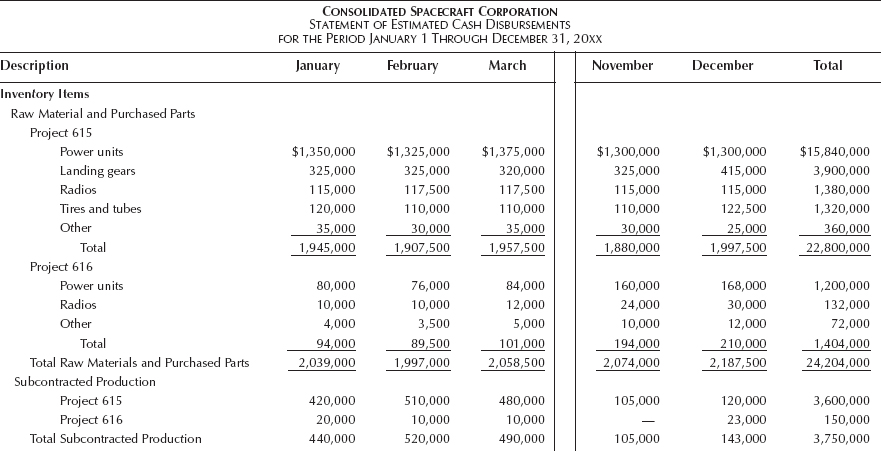

The material budget will set out the material requirements each month. The more important elements probably should be treated individually (e.g., power units or engines). Other items will be grouped together. Only in a few instances is material purchased for cash. However, reference to required inventories and to delivery dates as well as assistance from the purchasing department will establish the time allowed for payments. If 30 days are required, then usage of one month can be moved forward for the purpose of estimating cash payments. The effect of cash discounts should be considered in arriving at the estimated disbursements.

The various manufacturing and operating expenses should be considered individually because they are by no means all the same. Some are prepayments or accruals, paid annually, such as property taxes and insurance. Some are noncash items, such as depreciation expense or bad debts. For a large number of individually small items, such as supplies, telephone and telegraph, and traveling expense, an average time lag may be used.

Cash requirements for capital additions should be determined from the plant budget or other known plans. No particular difficulty presents itself because the needs are relatively fixed and are established by the board of directors or other authority.

Usual practice requires the determination of cash receipts and disbursements exclusive of transactions involving voluntary debt retirements, purchase of treasury stock, or funds from bank loans. Decisions relative to these means of securing or disbursing cash are reached when the cash position is known and policy formulated accordingly. When branch plants are involved, all such outlying activities must be consolidated to get the overall picture.

A typical cash disbursements budget is illustrated in Exhibit 8.4, with a format found practical for estimating purposes. The treatment of payments on other than a monthly basis is shown.

EXHIBIT 8.3 STATEMENT OF ESTIMATED CASH RECEIPTS BY SOURCE

EXHIBIT 8.4 STATEMENT OF ESTIMATED CASH DISBURSEMENTS

FASB Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 95: Statement of Cash Flows

Having discussed the two methods in general use for estimating cash flows, it may be appropriate to review the standard issued by the FASB relating to statements of cash flow. It could be relevant to the cash forecasting process if management desires that the internal estimating procedure closely parallel the format to be used in reporting cash flow to the investor or security analysts and others.

The cash reporting procedure prior to this standard in many instances suffered from these weaknesses:

- No common definition of cash. Should it include cash equivalents, compensating balances, postdated checks, and so forth?

- No common format. The format for the issuance of a cash flow statement was not distinguished from the statement of changes in financial condition.

- In many instances, it was difficult to identify the cash flows from normal operating activity. (They were combined with other cash producing/generating activities.) Thus, the potential investor was at a disadvantage in gauging the cash generating potential of the normal everyday activities.

The complete FASB Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 95, Statement of Cash Flows should be reviewed in its entirety by the controller. Though lengthy, the standard should be useful for many reasons, including:

- It provides examples of the cash flow formats that meet the standard for general purpose external financial accounting and reporting.

- It includes the many helpful definitions regarding cash flows from the three basic sources: operating, investing, and financing activities.

- It contains useful background data on cash flow statements and the basis of the FASB for reaching the conclusions it did.

- In addition to examples of statements of cash flow for a domestic manufacturing company, it provides an example of a statement of cash flows under the direct method for a domestic manufacturing company with foreign operations.

Some examples of current reporting practices are provided later in this chapter.

Relation of Cash Budget to Other Budgets

From the preceding discussion, it is readily apparent that preparation of the cash budget is generally dependent on other budgets—the sales forecast, the statement of estimated income and expense, the various operating budgets, the capital budget, and the long-range strategic plan. It is in reality part of a coordinated program of sales and costs correlated with business sheet changes and expected revenues and expenditures.

It can be appreciated, also, that the cash budget is a check on the entire budgetary program. If the operating budget goals are achieved, the results will be reflected in the cash position. Failure to achieve budgeted performance may result in the treasurer seeking additional sources of cash.

Depending on the financial position of the company, the cash forecast may have a high priority. Many executives prefer to review the cash forecast ahead of other projected statements, and it may, therefore, take the number one spot in the complete report on expected operations.

Length of Cash Budget Period

The length of the budget period depends on several factors, including the purpose the budget is to serve, the financial condition of the company, and the opinion of the executives about the practicality and accuracy of estimating. For illustration, a short-term forecast would be used in determining cash requirements, perhaps for one to three months in advance. But if the cash margin is low, an estimate of cash receipts and disbursements may be necessary on a weekly basis or even daily. On the other hand, a firm with ample cash may develop a cash forecast, by months, for six months, or a year in advance. For the determination of general financial policy a longer-term budget is necessary. Some companies feel that estimating beyond three months is inaccurate and restrict the cash budget to this period. Other companies maintain a running budget for three or more months in advance, always adding one month and dropping off the present month. A controller will have to adapt forecasting to the existing conditions. It may be necessary to prepare a short-term cash budget for cash requirements purposes and also a long-term forecast for use in financial policy decisions.

Putting the Cash Budget to Work

The controller can prepare the cash budget in the usual manner, indicating the extent of additional cash funds needed, if any, and the probable duration of such need. However, the responsibility for securing these funds on the most advantageous basis rests with the treasurer or chief financial officer. The treasurer, and not the chief accounting officer, would usually negotiate with banks for loans, or would invest surplus funds. Yet the part played by the controller is not always as routine as might appear. In times of adversity, the controller must be prepared to furnish extra information. Thus the treasurer may need to know the exact cash needs of the following week. This can be furnished by manually adding the bills payable at that time, as well as the payrolls. If the accounts payable are in the computer file, the requirements can be readily determined by tabulating the applicable due date file. The same procedure can be used in determining the funds, if any, to be transferred to each branch for the weekly period.

Cash requirements must be planned just as other operations are planned. It simply is not satisfactory to assume that a high volume of sales will automatically result in a sound financial position or that with a satisfactory budgeted profit and loss statement finances will take care of themselves. The controller can be an effective voice in establishing the necessity for a well-developed financial program.

CASH COLLECTIONS

Administration of Cash Receipts

One of the primary objectives of financial management is the conservation and effective utilization of cash. From the cash collection viewpoint, there are two phases of control: (1) the acceleration of collections, and (2) proper internal control of collections.

Acceleration of Cash Receipts

Two methods are commonly used to speed up the collection of receivables: the lockbox system and area concentration banking. The lockbox system involves the establishment of depository accounts in the various geographical areas of significant cash collections so that remittances from customers will take less time in transit, preferably not more than one day. Customers mail remittances to the company at a locked post office box in the region served by the bank. The bank collects the remittances and deposits the proceeds to the account of the company. Funds in excess of those required to cover costs are periodically transferred to company headquarters. Supporting documents accompanying remittances are mailed by the bank to the company. Collections are thus accelerated through reduction in transit time with resultant lower credit exposure. Arrangements must be made, however, for proper control of credit information.

Under the system of area concentration banking, local company units collect remittances and deposit them in the local bank. From the local bank, usually by wire transfers, expeditious movement of funds is made to a few area or regional concentration banks. Funds in excess of compensating balances are automatically transferred by wire to the company's banking headquarters. By this technique in-transit time is reduced.

The controller is expected to be aware of these and other devices for accelerating collections, and to assist the treasurer, should that be necessary.

While checks are the predominant means of collecting accounts receivable, an increasing amount of business is handled through electronic fund transfer (EFT). Moreover, there are various combinations of methods and instruments that speed collections:

- Lockbox

- Depository transfer check (DTC)

- Preauthorized draft (PAD)

- Automated clearinghouse (ACH) transfer (from one bank to another through the ACH system)

- Wire transfer

“Reports on Cash” on page 229 includes limited comments on the employment of the new technology in use and services that might be expected from the company's banking institutions.

Internal Control of Cash Receipts

In most business organizations, the usual routine cash transactions are numerous. The following sources are typical: mail receipts, over-the-counter cash sales, sales or collections made by salesmen, solicitors, and so on, and over-the-counter collections on account. Naturally, all businesses have other cash transactions of a less routine nature, such as receipts from the sale of fixed assets, that may be handled by the officers or require special procedures. Most of the cash problems will be found to center on the transactions just listed, because the more unusual or less voluminous cash receipts are readily susceptible to a simple check.

Regardless of the source of cash, the very basis for the prevention of errors or fraud is the principle of internal check. Such a system involves the separation of the actual handling of cash from the records relating to cash. It requires that the work of one employee be supplemented by the work of another. Certain results must always agree. For example, the daily cash deposit must be the same as the charge to the cash control account. This automatic checking of the work of one employee by another clearly discourages fraud and locates errors. Under such conditions, any peculations are generally restricted to cases of carelessness or collusion.

The system of internal control must be designed on the groundwork of the individual organization. However, there are some general suggestions that will be helpful to the controller in reviewing the situation:

- All receipts of cash through the mail should be recorded in advance of transfer to the cashier. Periodically, these records should be traced to the deposit slip.

- All receipts should be deposited intact daily. This procedure might also require a duplicate deposit slip to be sent by the bank or person making the deposit (other than the cashier) to an independent department—for use in subsequent check or audit.

- Responsibility for handling of cash should be clearly defined and definitely fixed.

- Usually, the functions of receiving cash and disbursing cash should be kept entirely separate (except in financial institutions).

- The actual handling of cash should be entirely separate from the maintenance of records, and the cashiers should not have access to these records.

- Tellers, agents, and field representatives should be required to give receipts, retaining a duplicate, of course.

- Bank reconciliations should be made by those not handling cash or keeping the records. Similarly, the mailing of statements to customers, including the check-off against the ledger accounts, should be done by a third party. The summarizing of cash records also may be handled by a third party.

- All employees handling cash or cash records should be required to take a periodic vacation, and someone else should handle the job during such absence. Also, at unannounced times, employees should be shifted in jobs to detect or prevent collusion.

- All employees handling cash or cash records should be adequately bonded.

- Mechanical and other protective devices should be used where applicable to give added means of check—cash registers, the tape being read by a third party; duplicate sales slips; daily cash blotters.

- Where practical, cash sales should be verified by means of inventory records and periodic physical inventories.

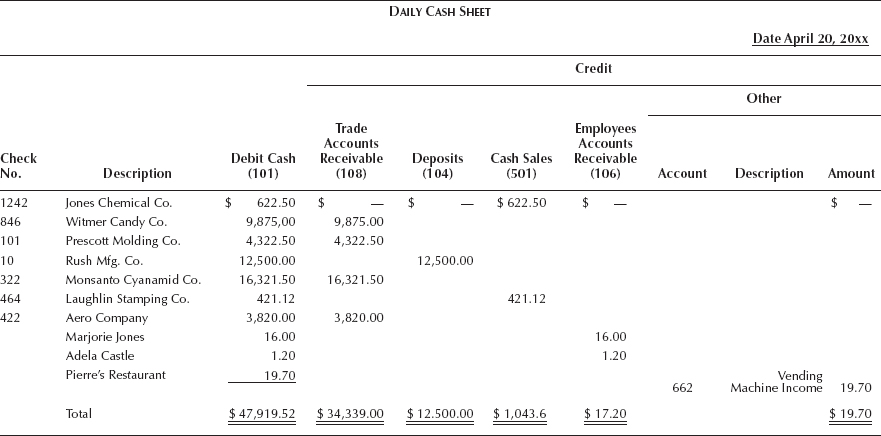

Illustrative Cash Receipts Procedure

A simple and effective cash receipts procedure can be executed that embodies some of the controls mentioned in the preceding section and that is adaptable by most industrial firms receiving cash by mail. All incoming mail not addressed to a specific individual is opened in the mailroom. Any mail containing remittances is listed on a daily remittance sheet prepared in triplicate. The name, check number, date, and amount are detailed on the record (Exhibit 8.5). One copy is forwarded, with the envelopes and remittance slips, to the cashier; a second goes to the auditor, treasurer, or controller; and the third copy is retained by the mailroom. The cashier records the cash received via the mailroom on a daily cash sheet or computer recording (Exhibit 8.6), indicating the nature of the receipt, along with any other receipts from other sources. This cash record is subsequently sent to the accounting department for posting, details as well as summary, after the cashier has made a summary entry. The deposit slip is prepared in quadruplicate. The cashier retains one copy. Three copies go to the bank for receipting, one of which is retained by the bank; another is returned to the cashier as evidence the bank received the funds; and a third is sent to the auditing department or controller's office. This is then compared in total, and occasionally in detail, with the daily cash register. The remittance sheet is also test-checked against the deposit slip. The cashier, of course, does not have access to the accounts receivable records, general ledger, or disbursements.

These basic methods may be adapted, in large degree, to personal computer systems.

EXHIBIT 8.5 MAILROOM REMITTANCE SHEET

Common Methods of Misappropriating Cash

An enumeration of some of the more common methods of misappropriating company funds may be a guide to the controller in recognizing points to guard against:

- Mail receipts

- (a) Lapping—diverting cash and reporting it some time after it has been collected; usually, funds received from one account are credited against another account from which cash has been diverted earlier

- (b) Borrowing funds temporarily, without falsifying any records, or simply not recording all cash received

- (c) Falsifying totals in the cashbook

- (d) Overstating discounts and allowances

- (e) Charging off a customer's account as a bad debt and pocketing the cash

- (f) Withholding of miscellaneous income, such as insurance refunds

EXHIBIT 8.6 DAILY CASH SHEET

- Over-the-counter sales

- (a) Failing to report all sales and pocketing the cash

- (b) Underadding the sales slip and pocketing the difference

- (c) Falsely representing refunds or expenditures

- (d) Registering a smaller amount than the true amount of sale

- (e) Pocketing cash overages

- Collections by salespeople

- (a) Conversion of checks made payable to “cash”

- (b) Failure to report sales

- (c) Overstating amount of trade-ins

Where adequate internal control is used, most of these practices cannot be carried on without collusion.

Other Means of Detecting Fraud

In addition to the segregation of duties that has been described, certain other practices may be adopted to further deter any would-be peculator or embezzler. One of these tools is surprise audits by the internal auditor as well as by the public accountants. Another is the prompt follow-up of past-due accounts. Proper instructions to customers about where checks should be mailed, and a specific request that they be made payable to the company, and not to any individual, also will help. Bonding of all employees, with a detailed check of references, is a measure of protection. Special checking of unusual receipts of a miscellaneous nature will tend to discourage irregularities.

For additional comments on internal control and fraud prevention, see Chapter 7.

CASH DISBURSEMENTS

Control of Cash Disbursements

In this area of cash administration, also, there are two aspects of control: (1) the timing of payments, and (2) the system of internal control.

Experience indicates the value of maintaining careful controls over the timing of disbursements to ensure that bills are paid only as they are due and not before. In such a manner, cash can be conserved for temporary investment.

Another consideration in payment scheduling is the conscious use of cash “float.” By recognizing in-transit items and the fact that ordinarily bank balances are greater than book balances because of checks not cleared, book balances of cash may be planned at lower levels. The incoming float may be balanced against the outgoing payments.

The relationship between the time a check is released to the payee and the time it clears the bank, the disbursement float, is made up of three elements:

- The time needed for the check to travel by mail or other delivery from the issuer to the payee

- The time required by the payee to process the check

- The period required by the banking system to clear the check, that is, the time from deposit by the payee to the time the item is charged to the issuer's account

In controlling this “float,” it often is helpful to trace the time interval of large checks to estimate the proper allowance for the period required for checks to clear. The controller should take measures to assure there is no abuse of float (e.g., writing of checks on banks in some remote location far from the recipient's address, so as to secure an additional three or four days of float).

Administrative Bank Accounts

In the control of disbursements, particularly where subsidiary or field office divisional trans-actions are involved, several special purpose bank accounts may be used (e.g., imprest accounts, zero balance accounts, and automatic balance accounts).

Under an imprest system, the unit operates with a fixed maximum balance. Periodically, such as weekly, or when the fund is below a minimum level, receipted bills are submitted for reimbursement.

With a zero balance account system, the clearing account for the organizational segment is kept at a zero balance. When checks are presented for payment, arrangements are such that the bank is authorized to transfer funds from the corporate general account to cover the items. Payment may be made by draft. Comparable arrangements can be made for the treasurer to make wire transfers to the zero bank account on notification of the items being presented for payment. Zero bank balance arrangements can facilitate control of payments through one or a limited number of accounts. The system may facilitate a quick check of the corporate cash position.

Automatic balance accounts use the same account for receipts and disbursements. When the account is above a specified maximum level, the excess funds are transferred to the central bank account; conversely, when the balance drops below a minimum level, the bank may call for replenishment.

INTERNAL CONTROL

Importance of Internal Control

Once the cash has been deposited in the bank, it would seem that the major problem of safeguarding the cash has been solved. Control of cash disbursements is a relatively simple matter—if a few rules are followed. After the vendor's invoice has been approved for payment, the next step usually is the preparation of the check for executive signature. If all disbursements are subject to this top review, how can any problem exist? Yet it is at precisely this point that the greatest danger is met. Any controller who has had to sign numerous checks knows that it is indeed an irksome task—the review to ascertain that receiving reports are attached, the checking of payee against the invoice, and the comparison of amounts. Because it is such a monotonous chore, it is often done in a most perfunctory manner. Yet this operation, carefully done, is essential to the control of disbursements. Where two signatures are required, both signatures need not make the detailed review, but certainly one should. The other can review on a spot-check basis only. There are too many instances where false documents and vouchers used a second time have been the means of securing executive signatures. Prevention of this practice demands careful review before signing checks, as well as other safeguards. It cannot be taken for granted that everything is all right. Those who sign the checks must adopt a questioning attitude on every transaction that appears doubtful or is not fully understood. Indeed, the review of documents attached to checks will often bring to light foolish expenditures and weaknesses in other procedures.

Some Principles of Internal Control

The opportunities for improper or incorrect use of funds are so great that a controller cannot unduly emphasize the need for proper safeguards in the cash disbursement function. Vigilance and sound audit procedures are necessary. Although the system of internal control must be tailored to fit the needs of the organization, some general suggestions may be helpful:

- Except for petty cash transactions, all disbursements should be made by check.

- All checks should be prenumbered, and all numbers accounted for as either used or voided.

- All general disbursement checks for amounts in excess of $x (e.g., $5000) should require two signatures.

- Responsibility for cash receipts should be divorced from responsibility for cash disbursements.

- All persons signing checks or approving disbursements should be adequately bonded.

- Bank reconciliations should be made by those who do not sign checks or approve payments.

- The keeping of cash records should be entirely separate from the handling of cash disbursements.

- Properly approved invoices and other required supporting documents should be a prerequisite to making every disbursement.

- Checks for reimbursement of imprest funds and payrolls should be made payable to the individual and not to the company or bearer.

- After payment has been made, all supporting documents should be perforated or otherwise mutilated or marked “paid” to prevent reuse.

- Mechanical devices should be used to the extent practical (check writers, safety paper, etc.)

- Annual vacations or shifts in jobs should be enforced for those handling disbursements.

- Approval of vouchers for payment usually should be done by those not responsible for disbursing.

- Special authorizations for interbank transfers should be required, and a clearing account, perhaps called Bank Transfers, should be maintained.

- All petty cash vouchers should be written in ink or typewritten.

- It may be desirable to periodically and independently verify the bona fide existence of the regularly used suppliers of recurring services (e.g., consultants, lawyers).

Methods of Misappropriating Funds

The safeguards just listed are some of those developed on the basis of experience by many firms. Some common means of perpetrating fraud are:

- Preparing false vouchers or presenting vouchers twice for payment

- “Kiting,” or unauthorized borrowing by not recording the disbursement, but recording the deposit, in the case of bank transfers

- Falsifying footing in cash records

- Raising the amount on checks after they have been signed

- Understating cash discounts

- Cashing unclaimed payroll or divided checks

- Altering petty cash vouchers

- Forging checks and destroying them when received from the bank, substituting other canceled checks or charge slips

Bank Reconciliations

An important phase of internal control is the reconciling of the balance per bank statement with the balance per books. This is particularly true with respect to general bank accounts as distinguished from accounts solely for disbursing paychecks. If properly done, the task is much more than a listing of outstanding checks, deposits in transit, and unrecorded bank charges. For example, the deposits and disbursements as shown on the bank statement should be reconciled with those on the books. A convenient form to handle this is illustrated in Exhibit 8.7. Then, too, it is desirable to compare endorsements with the payee and to check the payee against the record.

It has been mentioned previously that bank reconciliations should be handled by someone independent of any cash receipts or disbursements activities. The job can be handled by the controller or may be performed by the bank itself. Particular attention should be paid to outstanding checks of the preceding period and to deposits at the end of the month to detect kiting.

Petty Cash Funds

Most businesses must make some small disbursements. To meet these needs, petty cash funds are established that operate on an imprest fund basis, that is, the balances are fixed. At any time the cash, plus the unreimbursed vouchers, should equal the amount of the fund. Numerous funds of this type may be necessary in the branch offices or at each plant. A uniform receipt and uniform procedure should be provided, including limits on individual disbursements through this channel, proper approvals, and so forth. If it is practicable, the person handling cash receipts or disbursements should not handle petty cash. Other safeguards would include surprise cash counts, immediate cancellation of all petty cash slips after payment, and careful scrutiny of reimbursements. Although the fund may be small, very considerable sums can be expended. The controller should not neglect checking this activity.

Payrolls

In most concerns, payroll disbursements represent a very sizable proportion of all cash payments. Proper safeguards for this disbursement are particularly desirable. The use of a special payroll account is a very common procedure. A check in the exact amount of the total net payroll is deposited in the payroll account against which the individual checks are drawn. This has advantages from an internal control standpoint, and it may facilitate the reconciling of bank accounts.

The preparation of the payroll, of course, should be separate from the actual handling of cash. Special payroll audits are advisable—by the internal audit staff—to review procedures, verify rates, check clerical accuracy, and witness the payoff.

EXHIBIT 8.7 BANK RECONCILIATION

REPORTS ON CASH

Cash Reports for Internal Use

The cash reports used in most businesses are rather simple in nature but still provide important information. Reports on estimated cash requirements and balances or receipts or disbursements are illustrated in Exhibits 8.1 through 8.4.

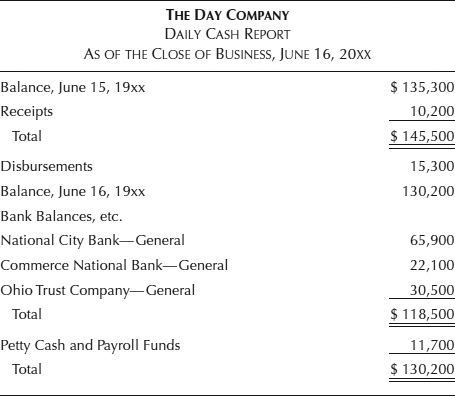

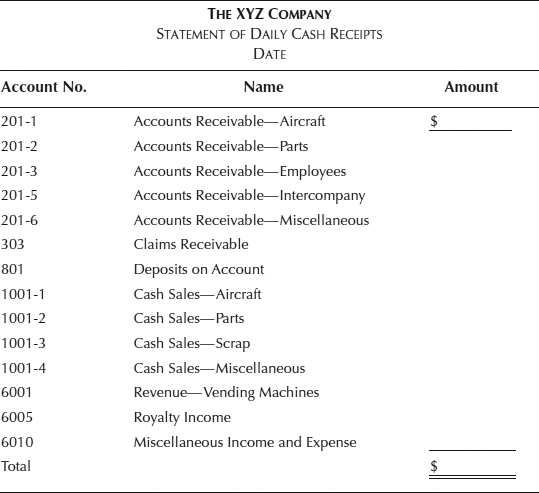

For information purposes, a simple daily cash report is prepared in some companies for the chief executive and treasurer. It merely summarizes the cash receipts and cash disbursements, as well as balances of major banks. An example is shown in Exhibit 8.8. Such a report may be issued daily, weekly, or monthly, depending on needs. A detailed statement of cash receipts is illustrated in Exhibit 8.9.

EXHIBIT 8.8 DAILY CASH REPORT

EXHIBIT 8.9 STATEMENT OF DAILY CASH RECEIPTS

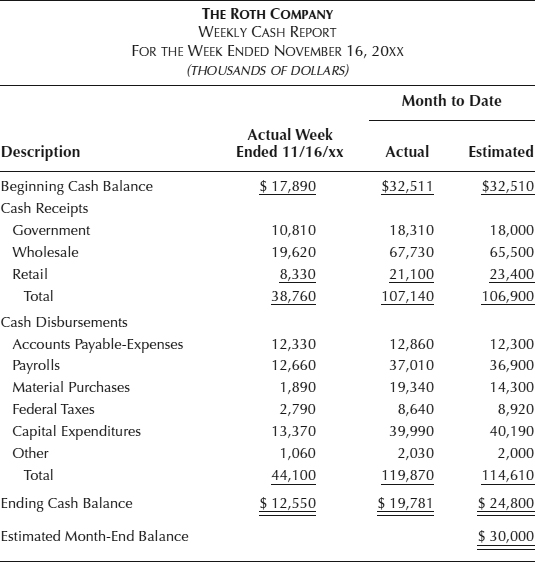

From the control viewpoint, it is desirable to know how collections and disbursements compare with estimates. Such information is shown in Exhibit 8.10, as well as the expected cash balance at month end.

EXHIBIT 8.10 COMPARISON OF ACTUAL AND ESTIMATED CASH ACTIVITY

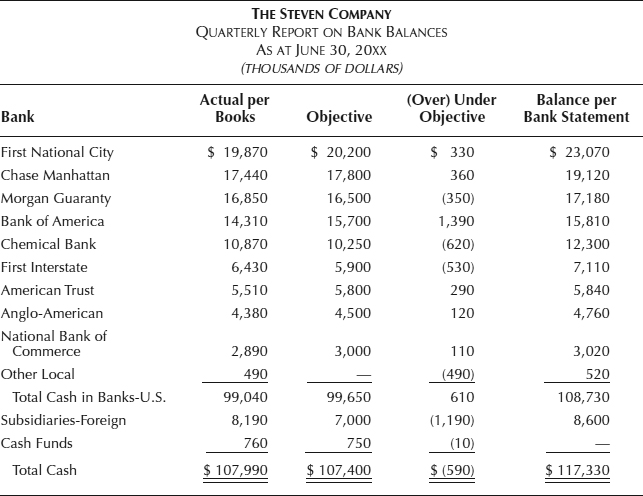

In addition to comparing actual and forecasted cash activity, it is also useful to periodically compare book balances with those required to meet service charges of the banks and compensating balances. Such a report compares the “objective” balance with actual book and actual bank balances. This type of report provides a periodic check on effective cash utilization by recording the absence of excessive balances and the progress in keeping bank balances adequate to fairly compensate the financial institution. A cash management report is shown in Exhibit 8.11.

There are any number of variations in cash reports, including some that are greatly detailed about daily cash receipts and the like. The suggested reports are merely examples; many may be adapted to computer applications.

Cash Flow Analysis for Investment Purposes

Cash flow is a broad measure of company performance. “Free cash flow,” a further refinement of cash flow in that from “cash flow” is subtracted a provision for required capital expenditures and, in some calculations, the dividend payments. In this latter case, the subtrahend is the equivalent of “discretionary funds,” and it represents sums that can be spent on acquisitions, stock buybacks, inventory, and many other items.

Where reported earnings are heavily reduced by depreciation, cash flow in some industries is an analytical yardstick of choice. It is useful to investors in spotting companies with ample resources to make them rewarding acquisitions. Additionally, corporate raiders are attracted to high cash flow situations because the cash stream may be used to pay down heavy debt incurred in a takeover. Periodically, listings appear comparing stock prices in terms of cash flow.

EXHIBIT 8.11 ACTUAL AND OBJECTIVE BANK BALANCES

The controller should be aware that cash flow may rank high in judging the investment worth of a company. It is a feature that usually deserves comment in any analytical effort.

CASH FLOW RATIO ANALYSIS

The requirement by the FASB for companies to provide shareholders (with access to the public and to potential investors) with a statement of cash flows, which identifies cash flows from operating activities, as well as that from investing activities and financing activities, has facilitated and encouraged the use of certain cash flow ratios. These ratios are useful in the planning and control of cash in that they may provide benchmarks or standards to measure the cash performance of a given company against other entities. Such comparisons may be helpful in evaluating financial performance of an acquisition target or other investments. Equally valuable, the ratios may be used to judge trends in the controller's own company and as compared with competitors or other selected best-in-their class entities.

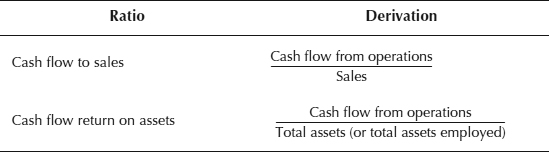

The cash flow ratios are of two types. The sufficiency ratios directly measure the ability of a company to generate enough cash flow to meet the needs of the entity, such as the ability to pay long-term debt, provide for needed plant and equipment, and pay dividends to the owners. The efficiency ratios indicate how well a company generates cash from selected measures, such as sales, income from continuing operations, and from total assets (or total assets employed).

Some sufficiency ratios and their derivatives are:

Some efficiency cash flow ratios are:

The cash efficiency ratios reflect the effectiveness or efficiency by which cash is generated from either operations or assets. Specifically:

- The cash flow-to-sales ratio reflects the percentage of each sales dollar realized as cash.

- The operations index reflects the ratio of cash generated to the income from continuing operations.

- The cash flow from assets reflects the relative amount of cash which the assets (or assets employed) are able to generate.

These ratios will assist in the analysis of financial statements. However, there is still a need for a consensus as to what are useful cash flow ratios, and the development of norms or standards for companies and industries.

IMPACT OF NEW INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES

The vast majority of the basic cash management functions described earlier in this chapter have been performed for years and will continue to be accomplished. But how they will be done, and what organization structure will do them (who) is subject to change. The pressures or influences that are causing or accelerating adjustments are many and include:

- The substantial improvements in information technology, or computer technology

- Growth in the global nature of business

- Economic pressures that are causing entities to integrate horizontally, to reduce staff size (such as treasury or controllership functions), to focus on the principal business, and to do more subcontracting or outsourcing

- Closer electronic integration with supplier, customer, or other third parties (such as banks)

The personal computer and the related software greatly aid in the analysis of data required for a cash forecast, as well as the actual preparation of the cash plan. As corporations and banks electronically integrate, there are many possibilities that should be of interest to the controller (for internal control and other purposes) including:

- Using an electronic data interchange (EDI) file, a customer can supply selling company's bank directly with invoice data and arrange payment. The bank will then update the payee's account.

- Where banks handle the lockbox operations, they can book images of remittance documents in a computer file and avoid enormous sorting and reassociation of check copies and the like. Less paperwork means less cost.

- Arrangements can be made with a company's bank for automatic payment of taxes and/or other designated items. This reduces float and provides greater control over the payment.

- Companies can arrange a system for electronic payment of selected supplier invoices thus reducing paperwork.

- For faster information, arrangements can be made for electronic account analysis.

- Banks can provide an automated check reconcilement through data transmission.

- Other systems have been developed by banks, using modern technology at the time of check presentments to reduce fraud.

Aside from the technology involved, companies can select banks to perform duties regularly handled by their own internal departments, such as portfolio management; cash collections, cash disbursements; payroll check preparation, retirement funds custody, accounting, and disbursements. Outsourcing of some financial activities is no longer a dirty word. Hopefully, the treasurer will have close contact with the company's banks in order to keep abreast of what services can be proved (more cheaply) on an outsourcing basis.

INVESTMENT OF SHORT-TERM FUNDS

In many companies, surplus or excess funds not needed for either operating purposes or compensating bank balances are available for investment, even over weekends. Prudent use of otherwise idle funds can add to income. Although the financial officer ordinarily will direct the investment of these funds, the controller may be concerned with adequate reporting and control and generally should be somewhat knowledgeable about the subject.

Criteria for Selecting Investments

Given the opportunity for earning additional income from temporary excess funds, what are some of the criteria to be considered in selecting the investment vehicle? There probably are five, and all somewhat related:

- Safety of principal. A primary objective should be to avoid instruments that might risk loss of the investment.

- Price stability. If the company is suddenly called on to liquidate the security to acquire funds, price stability would be important in avoiding a significant loss.

- Marketability. The money manager must consider whether the security can be sold, if required, rather easily and quite quickly.

- Maturity. Funds may be invested until the demand for cash arises, perhaps as reflected in the cash forecast. Hence maturities should relate to prospective cash needs. Temporary investments usually involve maturities of a day or two to as much as a year.

- Yield. The financial officer of course is interested in optimizing the earnings or securing at least a competitive return on the investment and is thus interested in the yield. This is not necessarily the most important criterion, because low-risk, high-liquidity investments will not provide the highest yield.

The importance attached to each of these factors will depend on the management philosophy, condition of the market, and inclinations of the investing person. Restrictions placed on the operation will influence the weighting of each.

Investment Restrictions

Sometimes the board of directors will place restrictions on just how short-term funds may be invested. In other instances, the senior financial officer will provide such guidelines. Subjects covered would include:

- Maximum maturity

- Credit rating of issuer

- Maximum investment in selected types of securities

- By user

- By type of instrument

- By country

- By currency

Instruments for investment vary widely, and market conditions may dictate the most desirable at any particular time. Typical money market instruments include:

- U.S. Treasury bills

- U.S. Treasury notes and bonds

- Negotiable certificates of deposit

- Banker's acceptances

- Selected foreign government issues

- Federal agency issues

- Repurchase agreements

- Prime commercial paper

- Finance company paper

- Short-term tax exempts

An illustration of the guidelines of an aerospace company for use in making temporary investments is shown in Exhibit 8.12.

EXHIBIT 8.12 GUIDELINES FOR SHORT-TERM INVESTMENTS

Investment Controls

Many securities that companies purchase as short-term investments are negotiable. Additionally, these investments often are paid for through bank wire transfers. Given the nature and frequency of transactions, the control system should be adequate.

Many corporations contract with a major commercial bank to serve as custodian of the securities, to make payment on incoming delivery, and to receive funds on outgoing delivery. The form of contract should provide maximum safeguards to the company.

Because opportunities for fraud exist, given telephonic transactions and wire transfer of funds, care must be exercised in the form and nature of confirmation secured and the internal controls used in authorizing payment.

Reports to Management

Periodic reports to top management, including the board of directors, will depend in part on this group's interest and the size of the investment portfolio. However, it is suggested, as a minimum, that where investments are significant, information should be conveyed regarding the type of investment and yield. Suggested report content would include:

- Detail of individual securities, grouped by type and/or maturity

- Summary by type

- Summary by maturity

- Summary by yield

- Overall portfolio yield, by maturity

- Comparison of yield with selected index or by money manager, if appropriate

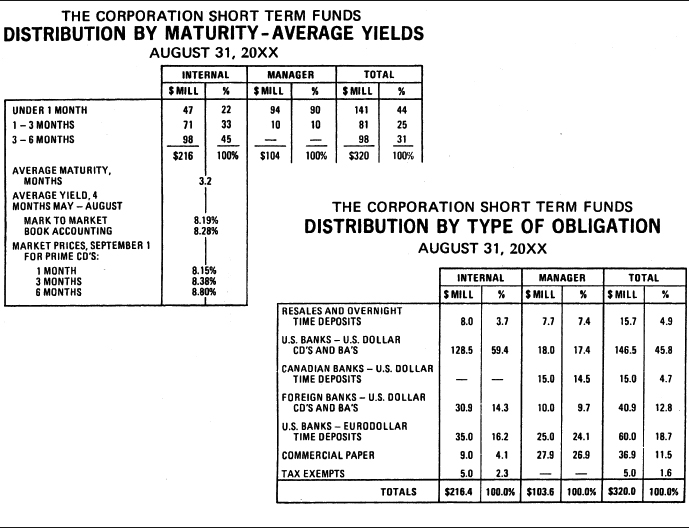

An illustrative report comparing in-house performance with an outside money manager is shown in Exhibits 8.13 through 8.14.

EXHIBIT 8.13 REPORT TO MANAGEMENT, BY ISSUER, ON SHORT-TERM INVESTMENTS

EXHIBIT 8.14 REPORT TO MANAGEMENT ON SHORT-TERM INVESTMENTS BY MATURITY AND TYPE OF OBLIGATION