Chapter 41

SHAREHOLDERS

What a cast of characters!

Section 41.1 SHAREHOLDER STRUCTURE

Our objective in this section is to demonstrate the importance of a company's shareholder structure. While the study of finance generally includes a clear description of why it is important to value a company and its equity, analysis of who owns its shares and how shareholders are organised is often neglected. Yet in practice this is where investment bankers often look first.

There are several reasons for looking closely at the shareholder base of a company. Firstly, the shareholders theoretically determine the company's strategy, but we must understand who really has power in the company, the shareholders or the managers. You will undoubtedly recognise the mark of “agency theory”. This theory provides a theoretical explanation of shareholder–manager problems.

Secondly, we must know the objectives of the shareholders when they are also the managers. Wealth? Power? Fame? In some cases, the shareholder is also a customer or supplier of the company. In an agricultural cooperative, for example, the shareholders are upstream in the production process. The cooperative company becomes a tool serving the needs of the producers, rather than a profit centre in its own right. This is probably why many agricultural cooperatives are not very profitable.

Lastly, disagreement between shareholders can paralyse a company, particularly a family-owned company.

As a last word, do not forget, as seen in Chapter 26, that in the financial world everything has a price, or better, everything can create or destroy value.

1/ DEFINITION OF SHAREHOLDER STRUCTURE

The shareholder structure (or shareholder base) is the percentage ownership and the percentage of voting rights held by different shareholders. When a company issues shares with multiple voting rights or non-voting preference shares or represents a cascade of holding companies, these two concepts are separate and distinct. A shareholder with 33% of the shares with double voting rights will have more control over a company where the remaining shares are widely held than will a shareholder with 45% of the shares with single voting rights if two other shareholders hold 25% and 30%. A shareholder who holds 20% of a company's shares directly and 40% of the shares of a company that holds the other 80% will have rights to 52% of the company's earnings but will be in the minority for decision-taking. In the case of companies that issue equity-linked instruments (convertible bonds, warrants, stock options) attention must be paid to the number of shares currently outstanding versus the fully diluted number of potential shares.

Studying the shareholder structure depends very much on the company being listed or not. In unlisted companies, the equilibrium between the different shareholders depends heavily on shareholders' agreements which are often in place, but rarely public and difficult to gain access to for the external analyst, impacting the relevancy of their analysis. For a listed company, shareholder attendance at previous general meetings should be analysed. If attendance has been low, a shareholder with a large minority stake could have de facto control, like Bolloré at Vivendi, in which it only has 29% of the voting rights.

Lastly, we should mention nominee (warehousing) agreements even though they are rarely used these days. Under a nominee agreement, the “real” shareholders sell their shares to a “nominee” and make a commitment to repurchase them at a specific price, usually in an effort to remain anonymous. A shareholder may enter into a nominee agreement for one of several reasons: transaction confidentiality, group restructuring or deconsolidation, etc. Conceptually, the nominee extends credit to the shareholder and bears counterparty and market risk. If the issuer runs into trouble during the life of the nominee agreement, the original shareholder will be loath to buy back the shares at a price that no longer reflects reality. As a result, nominee agreements are difficult to enforce. Moreover, they can be invalidated if they create an inequality among shareholders. We do not recommend the use of nominee agreements. The modern form for listed companies is the equity swap.1

2/ LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Theoretically, in all jurisdictions, the ultimate decision-making power lies with the shareholders of a company. They exercise it through the assembly of a shareholders' Annual General Meeting (AGM). Nevertheless, the types of decisions can differ from one country to another. Generally, shareholders decide on:

- appointment of board members;

- appointment of auditors;

- approval of annual accounts;

- distribution of dividends;

- changes in articles of association (i.e. the constitution of a company);

- mergers;

- capital increases and share buy-backs;

- dissolution (i.e. the end of the company).

In most countries – depending on the type of decision – there are two types of shareholder vote: ordinary and extraordinary.

At an Ordinary General Meeting (OGM) of shareholders, shareholders vote on matters requiring a simple majority of voting shares. These include decisions regarding the ordinary course of the company's business, such as approving the financial statements, payment of dividends and appointment and removal of members of the board of directors.

At an Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) of shareholders, shareholders vote on matters that require a change in the company's articles of association: share issues, mergers, asset contributions, demergers, share buy-backs, etc. These decisions require a qualified majority. Depending on the country and on the legal form of the company, this qualified majority is generally two-thirds or three-quarters of outstanding voting rights.

The main levels of control of a company in various countries are as follows:

| Supermajority | Type of decision | |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 1/2 | Changes in the objective of the company Merger, demerger Dissolution Changes in preferred share characteristics |

| China | 2/3 | Increase or reduction of the registered capital Merger, split-up Dissolution of the company Change of the company form |

| France | 2/3 | Changes in the articles of association Merger, demerger Capital increase and decrease Dissolution |

| Germany | 3/4 | Changes in the articles of association Reduction and increase of capital Major structural decisions Merger or transformation of the company |

| India | 3/4 | Merger |

| Italy | — | Defined in the articles of association |

| Netherlands | 2/3 | Restrictions in pre-emption rights Capital reduction |

| Russia | 3/4 | Changes in the articles of association Reorganisation of the company Liquidation Reduction and increase in capital Purchase of own shares Approval of a deal representing more than 50% of the company's assets |

| Spain | — | Defined in the articles of association |

| Switzerland | 2/3 | Changes in purpose Issue of shares with increased voting powers Limitations of pre-emption rights Change of location Dissolution |

| UK | 3/4 | Altering the articles of association Disapplying members' statutory pre-emption rights on issues of further shares for cash Capital decrease Approving the giving of financial assistance/purchase of own shares by a private company or, off market, by a public company Procuring the winding up of a company by the court Voluntarily winding up a company |

| USA | — | Defined on a state level and frequently in the articles of association |

Shareholders holding less than the blocking minority (if this concept exists in the country) of a company that has another large shareholder with a majority, have a limited number of options open to them. They cannot change the company objectives or the way it is managed. At best, they can force compliance with disclosure rules, or call for an audit or an EGM. Their power is most often limited to being that of a naysayer. In other words, a small shareholder can be a thorn in management's side, but no more. Nevertheless, the voice of the minority shareholder has become a lot louder and a number of them have formed associations to defend their interests. Shareholder activism has become a defence tool where the law had failed to provide one.

It should be noted that in some countries (Sweden, Norway, Portugal) minority shareholders can force the payment of a minimum dividend. In some countries, all shareholders, irrespective of the number of shares they hold, have the right to ask questions in writing at the General Meeting. The company must answer them publicly at the latest on the day of the meeting.

A shareholder who holds a blocking minority (one-quarter or one-third of the shares plus one share depending on the country and the legal form of the company) can veto any decision taken in an extraordinary shareholders' meeting that would change the company's articles of association, company objects or called-up share capital.

A blocking minority is in a particularly strong position when the company is in trouble, because it is then that the need for operational and financial restructuring is the most pressing. The power of blocking minority shareholders can also be decisive in periods of rapid growth, when the company needs additional capital.

The notion of a blocking minority is closely linked to exerting control over changes in the company's articles of association. Consequently, the more specific and inflexible the articles of association are, the more power the holder of a blocking minority wields.

3/ THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF SHAREHOLDERS

(a) The family-owned company

By “family-owned” we mean that the shareholders have been made up of members of the same family for several generations and, often through a holding company, exert significant influence over management. This is still the dominant model in Europe. The following table shows the shareholder base of the 50 largest companies by market capitalisation in several countries (2021):

| Shareholding | Germany | Switzerland | USA | France | Italy | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widely spread | 50% | 54% | 84% | 43% | 20% | 82% |

| Family (and non-listed) | 20% | 32% | 14% | 31% | 38% | 6% |

| State and local authorities | 10% | 8% | 0% | 14% | 22% | 4% |

| Financial institution | 2% | 4% | 0% | 6% | 12% | 6% |

| Other listed firms | 18% | 2% | 2% | 6% | 8% | 2% |

Source: Company data, FactSet.

However, this type of shareholder structure is on the decline for several reasons:

- some new or capital-intensive industries, such as energy/utilities and banks require so much capital that a family-owned structure is not viable over the long term. Indeed, family ownership is more suited to consumer goods, retailing, services, processing, etc.;

- financial markets have matured and financial savings are now properly rewarded, so that, with rare exceptions, diversification is a better investment strategy than concentration on a specific risk (see Section 18.6);

- increasingly, family-owned companies are being managed on the basis of financial criteria, prompting the family group either to exit the capital or to dilute the family's interests in a larger pool of investors that it no longer controls. This trend requires a nuanced view as, in recent years, certain young companies whose founders remain very important shareholders (Contentsquare, Doordash, Iliad, and so on) have taken up a prominent role within the economy.

Family shareholding sometimes reappears in the form of family offices, emanating from large industrial families (Desmarais in Canada, Quandt in Germany, Frère in Belgium, etc.) that invest in financial fundamentals, but with a much longer-term perspective than traditional funds.

Some research has demonstrated that family-owned companies register on average better performance than non-family-owned companies. Having most of your wealth in one single company or group is a strong incentive to properly monitor its managers or to act responsibly as its manager.

(b) Business angels

See Chapter 40.

(c) Private equity funds

Private equity funds, financed by insurance companies, pension funds or wealthy investors, play a major role. In most cases these funds specialise in a certain type of investment: venture capital, development capital, LBOs (see Chapter 47) or turnaround capital, which correspond to a company's different stages of maturity.

Venture capital funds focus on bringing seed capital, i.e. equity, to start-ups to finance their early developments.

Development capital funds become shareholders of high-growth companies that require substantial funds.

LBO funds invest in companies put up for sale by a group looking to refocus on its core business or by a family-held group faced with succession problems, or help a company whose shares are depressed (in the opinion of the management) to delist itself in a public-to-private (P-to-P) transaction. LBO funds are keen to get full control over a company (but control can be exercised by 2 or 3 funds) in order to reap all of the rewards and also to make it possible to restructure the company as they think best, without having to worry about the interests of minority shareholders. Therefore, they usually prefer the target companies not to be listed (or to be delisted if the target was public), but the fund itself can be listed.

Turnaround funds work with distressed companies, helping them to turn themselves around.

Activist funds have made a speciality of putting public pressure on poorly performing or badly structured groups, proposing corrective measures to improve their value. In 2020, for example, Amber was proposing a complete overhaul of Lagardère's board of directors, a change of strategy and the abandonment of the limited partnership status that protects the founder's heir, who has not demonstrated the same qualities. This has been implemented in 2021.

Managed by teams of investment professionals whose compensation is largely linked to performance, these funds have a limited lifespan (no more than 10 years). Before the fund is closed, the companies that the fund has acquired are resold, floated on the stock exchange or the fund's investments are taken over by another fund.

Some private equity funds take a minority stake in listed companies, a PIPE (private investment in public equity), helping the management to revitalise the company so as to make a capital gain. For example, in 2019, Searchlight Capital took a 26% stake in Latécoère and changed the CEO in 2020. In 2020–2021, the creation of SPACs by private equity funds allowed them to invest in companies on a minority basis when they went public using this technique.

Private equity funds play an important role in the economy and are a real alternative to a listing on the stock exchange. They solve agency problems by putting in place strict reporting from the management, which is incentivised through management packages and the pressure of debt (LBO funds).

They also bring a cash culture to optimise working capital management and limit capital expenditure to reasonably value-creating investments. Private equity funds are ready to bring additional equity to finance acquisitions with an industrial logic. They also bring to management a capacity to listen, to advise and to exchange, which is far greater than that provided by most institutional investors. They are professional shareholders who have only one aim – to create value – and they do not hesitate to align the management of companies they invest in with that objective.

(d) Institutional investors

Institutional investors are banks, asset managers, insurance companies, pension funds and unit trusts that manage money on behalf of private individuals. Most of the time they individually own minor stakes (less than 10%), but they play a much bigger role as they define the stock market price of companies in which they collectively represent the major part of their floating capital.

Because of new regulations on corporate governance (see Chapter 43), they vote at AGMs more frequently, especially to defeat resolutions they do not like, notably regarding excessive compensation.

(e) Financial holding companies

Large European financial holding companies such as Deutsche Bank, Paribas, Mediobanca, Société Générale de Belgique, etc. played a major role in creating and financing large groups. In a sense, they played the role of the (then-deficient) capital markets. Their gradual disappearance or mutation has led to the breakup of core shareholder groups and cross-shareholdings. Today, in emerging countries (Korea, India, Colombia), large industrial and financial conglomerates play their role (Samsung, Tata, Votorantim, etc.).

(f) Employee-shareholders

Many companies have invited their employees to become shareholders. In most of these cases, employees hold a small proportion of the shares, although in a few cases the majority of the shares. This shareholder group, loyal and non-volatile, lends a degree of stability to the capital and, in general, strengthens the position of the majority shareholder, if any, and of the management.

The main schemes to incentivise employees are:

- Direct ownership. Employees and management can invest directly in the shares of the company. In LBOs, private equity sponsors bring the management into the shareholding structure to minimise agency costs.

- Employee stock ownership programmes (ESOPs). ESOPs consist in granting shares to employees as a form of compensation. Alternatively, the shares are acquired by shareholders but the firm will offer free shares so as to encourage employees to invest in the shares of the company. The shares will be held by a trust (or employee savings plan) for the employees. Such programmes can include lock-up clauses to maintain the incentive aspect and limit flowback (see Section 25.2). In this way, the shares allocated to each employee will vest (i.e. become available) gradually over time.

- Stock options. Stock options are a right to subscribe to new shares or shares held by the company as treasury stocks at a certain point in time.

For service companies and fast-growing companies, it is key to incentivise employees and management with shares or stock options, as the key assets of such companies are their people. For other companies, offering stock to employees can be part of a broader effort to improve employee relations (all types of companies) and promote the company's image internally. The success of such a policy largely depends on the overall corporate mood. In large companies, employees can hold up to 10%. Lehman, the US investment bank, was one of the listed companies with the largest employee shareholdings (c. 25%) when it went into meltdown in 2008.

Regardless of the type of company and its motivation for making employees shareholders, you should keep in mind that the special relationship between the company and the employee-shareholder cannot last forever. Prudent investment principles dictate that the employee should not invest too heavily in the shares of the company that pays their salaries, because in so doing they, in fact, compound the “everyday life” risks they are running.2

Basically, the company should be particularly fast-growing and safe before the employee agrees to a long-term participation in the fruits of its expansion. Most often, this condition is not met. Moreover, just because employees hold stock options does not mean they will be loyal or long-term shareholders. The LBO models we will study in Chapter 47 become dangerous when they make a majority of the employees shareholders. In a crisis, the employees may be keener to protect their jobs than to vote for a painful restructuring. When limited to a small number of employees, however, LBOs create a stable, internal group of shareholders.

(g) Governments

In Europe and the USA, governments' role as the major shareholders of listed groups is fading, even if they are still majority shareholders of large industry players (Deutsche Bahn, EDF, Enel) or playing a key role in some groups like Deutsche Telekom, Airbus or Eni. State ownership had a period of revival thanks to the economic crisis, as some groups were taken over to avoid collapse (General Motors, RBS) or funds were injected through equity issues to reinforce financial institutions (Citi, ING, etc.).

At the same time, sovereign wealth funds, mostly created by emerging countries and financed thanks to reserves from staples, are gaining importance as long-term shareholders. They are normally very financially minded, but their opacity, their size (often between €50bn and €500bn) and their strong connections with mostly undemocratic states are worrying to some. As of end 2020, they had c. $9,070bn under management, and slowly growing. The most well-known include The Government Pension Fund of Norway, Norges ($1,290bn), China Investment Company (CIC, $1,045bn), SAFE Investment Company and Hong Kong Monetary Authority ($978bn) from China, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA, $745bn), GIC and Temasek in Singapore ($710bn), Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA, $562bn), etc. They are majority shareholders of a number of firms (Singapore Airlines, P&O, etc.) and minority shareholders in some listed firms such as the London Stock Exchange, Glencore, KKR, Carlyle, Foncia, etc.

(h) Crossholdings

Crossholdings peaked before the 1990s when capitalism was often capital-less. Today, the very few examples (Renault owns 43% of Nissan, which owns 15% of Renault, Spotify owns 9% of Tencent Music, which owns 7.5% of Spotify) are there to promote industrial synergies, or even to prepare for a closer future relationship, and not for financial or power reasons.

4/ SHAREHOLDERS' AGREEMENT

Minority shareholders can protect their interests by crafting a shareholders' agreement with other shareholders.

A shareholders' agreement is a legal document signed by several shareholders to define their future relationships. It complements the company's articles of association. Most of the time, the shareholders' agreement is confidential except for listed companies in countries which require its publication in order for it to be valid.

They mainly contain two sets of clauses:

- clauses that organise corporate governance: breakdown of directors' seats, the nomination of the chairperson, of the CEO, of the auditors; how major decisions are taken, including capex; financing, acquisitions, share issues, dividend policy; how to vote during annual general meetings; what kind of information is disclosed to shareholders, etc.;

- clauses that organise the sale or purchase of shares in the future: lock-up, right of first refusal if one shareholder wants to exit, drag-along (to force the disposal of 100% of the shares if the majority shareholders or several shareholders holding a majority stake between them wish to exit) or tag-along (to allow minority shareholders to benefit from the same transaction conditions if the majority shareholder is selling), caps and floors, etc.

- For shareholders' agreement on start-ups, please see Section 40.4.

Section 41.2 HOW TO STRENGTHEN CONTROL OVER A COMPANY

Defensive measures for maintaining control of a company always carry a cost. From a purely financial point of view, this is perfectly normal: there are no free lunches!

With this in mind, let us now take a look at the various takeover defences. We will see that they vary greatly depending on the country, on the existence or absence of a regulatory framework and on the powers granted to companies and their executives. Certain countries, such as the UK and, to a lesser extent, France and Italy, regulate anti-takeover measures strictly, while others, such as the Netherlands and the USA, allow companies much more leeway.

Broadly speaking, countries where financial markets play a significant role in evaluating management performance, because companies are more widely held, have more stringent regulations. This is the case in the UK and France.

Conversely, countries where capital is concentrated in relatively few hands have more flexible regulation. This goes hand in hand with the articles of association of the companies, which ensure existing management a high level of protection. In Germany, half of the seats on the board of directors are reserved for employees, and board members can be replaced only by a 75% majority vote.

Paradoxically, when the market's power to inflict punishment on companies is unchecked, companies and their executives may feel such insecurity that they agree to protect themselves via the articles of association. Sometimes this contractual protection is to the detriment of the company's welfare and of free market principles. This practice is common in the US.

Defensive measures fall into four categories:

- Separate management control from financial control:

- different classes of shares: shares with multiple voting rights and non-voting shares;

- holding companies;

- limited partnerships.

- Control shareholder changes:

- right of approval;

- pre-emption rights.

- Strengthen the position of loyal shareholders:

- reserved capital increases;

- share buy-backs and cancellations;

- mergers and other tie-ups;

- employee shareholdings;

- warrants.

- Exploit legal and regulatory protection:

- regulations;

- voting caps;

- strategic assets;

- change-of-control provisions.

In order to defend itself, a company must know who its shareholders are. This is relatively easy for unlisted companies for which shares must be nominative, but a lot more complicated for listed companies, where most of the shares are bearer shares (the identity of the shareholder is unknown to the company). In this way, some companies are able to make provision for the notification obligation, set out in the articles of association, when a minimum threshold (0.5%, for example) of the share capital has been breached, which is in addition to statutory obligations starting at 3 or 5% in most countries (see Section 45.3).

1/ SEPARATING MANAGEMENT CONTROL FROM FINANCIAL CONTROL

(a) Different classes of shares: shares with multiple voting rights and non-voting shares

As an exception to the general rule, under which the number of votes attributed to each share must be directly proportional to the percentage of the capital it represents (principle of one share, one vote), companies in some countries have the right to issue multiple-voting shares or non-voting shares.

In the Netherlands, the USA, Luxembourg, and the Scandinavian countries, dual classes of shares are not infrequent. The company issues two (or more) types of shares (generally named A shares and B shares) with the same financial rights but with different voting rights.

French corporate law provides for the possibility of double-voting shares but, contrary to dual-class shares, all shareholders can benefit from the double-voting rights if they hold the shares for a certain time.

Multiple-voting shares can be particularly powerful; for example, the founders of Alphabet (ex. Google) have 53.1% of voting rights of Alphabet while they hold only 11.6% of the shares. Ford, Snap, Lyft, Facebook, and Roche, have also put in place this type of capital structure. These dual-class shares can appear as unfair and contrary to the principle that the person who provides the capital gets the power in a company. Some countries (Italy, Spain, Belgium and Germany) have outlawed dual-class shares.

(b) Holding companies

Holding companies can be useful but their intensive use leads to complex, multi-tiered shareholding structures. As you might imagine, they present both advantages and disadvantages.

Suppose an investor holds 51% of a holding company, which in turn holds 51% of a second holding company, which in turn holds 51% of an industrial company. Although they hold only 13% of the capital of this industrial company, the investor uses a cascade of holding companies to maintain control of the industrial company.

A holding company allows a shareholder to maintain control over a company, because a structure with a holding disperses the minority shareholders. Even if the industrial company were floated on the stock exchange, the minority shareholders in the different holding companies would not be able to sell their stakes.

Maximum marginal personal income tax is generally higher than income taxes on dividends from a subsidiary. Therefore, a holding company structure allows the controlling shareholder to draw off dividends with a minimum tax bite and use them to buy more shares in the industrial company.

Technically, a holding company can “trap” minority shareholders; in practice, this situation often leads to an ongoing conflict between shareholders. For this reason, holding companies are usually based on a group of core shareholders intimately involved in the management of the company.

A two-tiered holding company structure often exists, where:

- a holding company controls the operating company;

- a top holding company holds the controlling holding company. The shareholders of the top holding company are the core group. This top holding company's main purpose is to buy back the shares of minority shareholders seeking to sell some of their shares.

Often, a holding company is formed to represent the family shareholders prior to an IPO.

(c) Limited share partnerships (LSPs)

A limited share partnership is a company where the share capital is divided into shares, but with two types of partners:

- several limited partners with the status of shareholders, whose liability is limited to the amount of their investment in the company. A limited share partnership is akin to a public limited company in this respect;

- one or more general partners, who are jointly liable, to an unlimited extent, for the debts of the company. Senior executives of the company are usually general partners, with limited partners being barred from the executive suite.

The company's articles of association determine how present and future executives are to be chosen. These top managers have the most extensive powers to act on behalf of the company in all circumstances. They can be fired only under the terms specified in the articles of association. In some countries, the general partners can limit their financial liability by setting up a (limited liability) family holding company. In addition, the LSP structure allows a change in management control of the operating company to take place within the holding company. For example, a father can hand over the reins to his daughter, while the holding company continues to perform its management functions.

Thus, theoretically, the chief executive of a limited share partnership can enjoy absolute and irrevocable power to manage the company without owning a single share. Management control does not derive from financial control as in a public limited company, but from the stipulations of the by-laws, in accordance with applicable law. Several large listed companies have adopted limited share partnership form, including Merck KGaA, Henkel, Michelin and Hermès.

(d) Non-voting shares

Issuing non-voting shares is similar to issuing dual-class shares because some of the shareholders will bring capital without getting voting power. Nevertheless, issuing non-voting shares is a more widely spread practice than issuing dual-class shares. Actually, in compensation for giving up their voting rights, holders of non-voting shares usually get preferential treatment regarding dividends (fixed dividend, higher dividend compared to ordinary shares, etc.). Accordingly, non-voting (preference) shares are not perceived as unfair but as a different arbitrage for the investor between return, risk and power in the company. For more, see Section 24.3.

2/ CONTROLLING SHAREHOLDER CHANGES

(a) Right of approval

The right of approval, written into a company's articles of association, enables a company to avoid “undesirable” shareholders or shift the balance between shareholders. This clause is frequently found in family-owned companies or in companies with a delicate balance between shareholders. The right of approval governs the relationship between partners or shareholders of the company; be careful not to confuse it with the type of approval required to purchase certain companies (see below).

Technically, the right of approval clause requires all partners to obtain the approval of the company prior to selling any of their shares to a third party, or to another shareholder if explicitly provided for in the approval clause. The company must render its decision within a specified time period. If no decision is rendered, the approval is deemed granted.

If it refuses, the company, its board of directors, executive committee, senior executives or a third party must buy back the shares within a specified period of time, or the shareholder can consummate the initially planned sale.

The purchase price is set by agreement between the parties, or in the event that no agreement is reached, by independent appraisal.

Right of approval clauses might not be applied when shares are sold between a shareholder, their spouse or their immediate family and descendants.

Most of the time, right of approval clauses for listed companies are prohibited as they run contrary to the fluidity implied in being a public company.

(b) Pre-emption rights

Equivalent to the right of approval, the pre-emption clause gives a category of shareholders or all shareholders a priority right to acquire any shares offered for sale. Companies whose existing shareholders want to increase their stake or control changes in the capital use this clause. The board of directors, the chief executive or any other authorised person can decide how shares are divided amongst the shareholders.

Technically, pre-emption rights procedures are similar to those governing the right of approval.

Most of the time, pre-emption rights do not apply in the case of inherited shares, liquidation of a married couple's community property, or if a shareholder sells shares to their spouse, immediate family or descendants.

Right of approval and pre-emption rights clauses constitute a means of controlling changes in the shareholder structure of a company. If the clause is written into the articles of association and applies to all shareholders, it can prevent any undesirable third party from obtaining control of the company. These clauses cannot block a sale of shares indefinitely, however. The existing shareholders must always find a solution that allows a sale to take place if they do not wish to buy.

3/ STRENGTHENING THE POSITION OF LOYAL SHAREHOLDERS

(a) Reserved share issues

In some countries, a company can issue new shares on terms that are highly dilutive for the existing shareholders. For example, to fend off a challenge from the newspaper group Gannet, the Tribune Publishing group (publisher of The Chicago Tribune and The Los Angeles Times) issued 13% of its share capital in May 2016 to Patrick Soon-Shiong, placing the billionaire as Tribune's second-largest shareholder.

The new shares can be purchased either for cash or for contributed assets. For example, a family holding company can contribute assets to the operating company to strengthen its control over this company.

(b) Mergers

Mergers are, first and foremost, a method for achieving strategic and industrial goals. As far as controlling the capital of a company is concerned, a merger can have the same effect as a reserved capital increase, by diluting the stake of a hostile shareholder or bringing in a new friendly shareholder. We will look at the technical aspects in Chapter 46.

The risk, of course, is that the new shareholders, initially brought in to support existing management, will gradually take over control of the company.

(c) Share buy-backs and cancellations

This technique, which we studied in Chapter 37 as a financial technique, can also be used to strengthen control over the capital of a company. The company offers to repurchase a portion of outstanding shares with the intention of cancelling them. As a result, the percentage ownership of the shareholders who do not subscribe to the repurchase offer increases. In fact, a company can regularly repurchase shares. For example, Bic and Norilsk Nickel have used this method several times in order to strengthen the control of large shareholders.

(d) Employee shareholdings

Employee-shareholders generally have a tendency to defend a company's independence when there is a threat of a change in control. A company that has taken advantage of the legislation favouring different employee share-ownership schemes can generally count on a few percentage points of support in its effort to maintain the existing equilibrium in its capital. In 2007, for example, the employee-shareholders of the construction group Eiffage rallied behind management in its effort to see off Sacyr's rampant bid.

(e) Warrants

The company issues warrants to certain investors. If a change in control threatens the company, investors exercise their warrants and become shareholders. This issue of new shares will make a takeover more difficult, because the new shares dilute the ownership stake of all other shareholders. The strike price of the warrant is usually very attractive but the warrants can only be exercised if a takeover bid is launched on the company.

This type of provision is common in the Netherlands (ING or Philips), France (Peugeot, Bouygues) and the US. In 2018, both Bouygues' and Peugeot's AGM authorised their boards to issue such warrants should they find it necessary.

4/ LEGAL AND REGULATORY PROTECTION

(a) Regulations

Certain investments or takeovers require approval from a government agency or other body with vetoing power. In most countries, sectors where there are needs for specific approval are:

- financial institutions;

- activities related to defence (for national security reasons);

- media;

- etc.

Golden shares are special shares that enable governments to prevent another shareholder from increasing its stake above a certain threshold, or the company from selling certain of its assets (Distrigas, Telecom Italia, Eni are some examples).

(b) Voting caps

In principle, the very idea of limiting the right to vote that accompanies a share of stock contradicts the principle of “one share, one vote”. Nevertheless, in some countries, companies can limit the vote of any shareholder to a specific percentage of the capital. In some cases, the limit falls away once the shareholder reaches a very large portion of the capital (e.g. 50% or 2/3).

For example, Danone's articles of association stipulate that no shareholder may cast more than 6% of all single voting rights and no more than 12% of all double voting rights at a shareholders' meeting, unless they own more than two-thirds of the shares. Voting caps are commonly used in Europe, specifically in Switzerland (12 firms out of the 50 largest use them), France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain. Nestlé, Total, and Novartis all use voting caps.

This is a very effective defence. It prevents an outsider from taking control of a company with only 20% or 30% of the capital. If they truly want to take control, they have to “up the ante” and bid for all of the shares. We can see that this technique is particularly useful for companies of a certain size. It makes sense only for companies that do not have a strong core shareholder.

(c) Strategic assets (poison pills)

Strategic assets can be patents, brand names or subsidiaries comprising most of the business or generating most of the profits of a group. In some cases the company does not actually own the assets but simply uses them under licence. In other cases these assets are located in a subsidiary with a partner who automatically gains control should control of the parent company change hands. Often contested as misuse of corporate property, poison pill arrangements are very difficult to implement, and in practice are generally ineffective. In 2021, Suez tried to fend off Veolia's bid by housing its French water business in a foundation in the Netherlands to make it non-transferable.

(d) Change-of-control provisions

Some contracts may include a clause whereby the contract becomes void if one of the control provisions over one of the principles of the contract changes. The existence of such clauses in vital contracts for the company (distribution contract, bank debt contract, commercial contract) will render its takeover much more complex.

Some “golden parachute” clauses in employment contracts allow employees to leave the company with a significant amount of money in the event of a change of control, which consequently has a dissuasive effect.

Section 41.3 STOCK MARKET OR INVESTMENT FUND SHAREHOLDING?

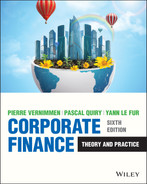

The disenchantment with stock markets and the rise of unlisted investments is a fundamental trend that is not about to stop. While the number of listed companies worldwide has stagnated since 2015 at just over 50,000, in the United States it has been declining since 1997, now less than half the number of the companies listed on the stock exchange as in 1997.

Source: Data from World Federation of Exchanges

As nature abhors a vacuum and with companies less attracted by the stock market, investment in unlisted, or private, equity is growing apace. Its precise definition is unclear and differs from one source to another. Let's say that it covers all investments made through investment funds in unlisted companies or companies that become unlisted on that occasion, or in unlisted assets (such as real estate or natural resources).

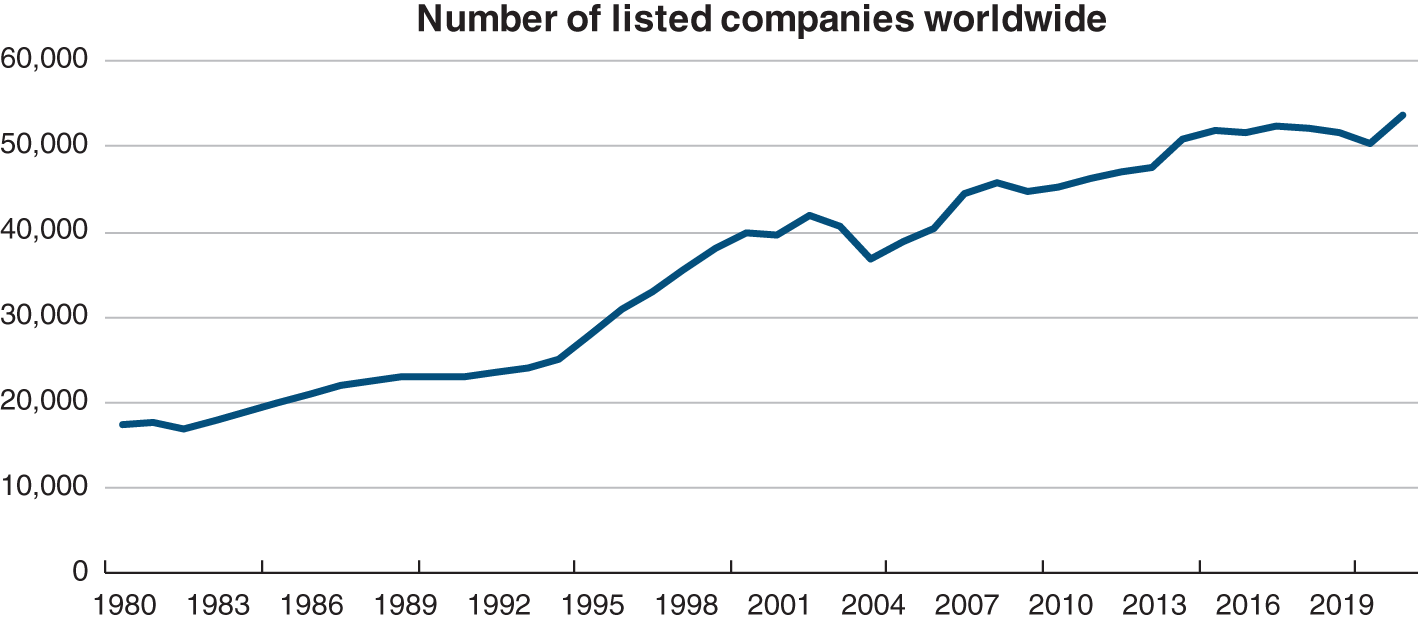

Preqin estimates that private equity funds raised in 2020 amounted to $989bn significantly higher than pre-2008 records:

Source: Data from Preqin, quoted in ‘Global private equity report 2021’, Bain & Company

Even if 2020 was a record year for IPOs ($353bn), the funds provided by private equity remain much higher.

1/ THE ORIGIN OF INVESTMENT FUNDS

The origins of unlisted investment in its modern form can be traced back to the United States when, after the Second World War, a Harvard management professor, Georges Doriot, set up the world's first venture capital company, AR&D, in the Boston area. With funds provided in particular by the John Hancock insurance company and MIT, AR&D financed DEC from its beginnings in 1957, which was a huge success and became the second largest computer manufacturer in the world before its takeover in 1999 by Compaq, which itself merged with HP in 2002.

In the United Kingdom, private equity initially took the form of minority investments to help SMEs or second tier companies to grow and turn into groups. The unlisted, fund-managed sector developed later in continental Europe, where development capital had been pre-empted at the beginning of the 20th century by listed financial companies, the best known of which were Mediobanca, Paribas, Suez, Générale de Belgique, Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank, etc.

Then in the 1980s, a genetic mutation took place in the world of unlisted investing with the appearance and then the development of LBO funds3 taking full control of a target, a new occurrence as unlisted investing had previously limited itself to minority stakes. The refocusing of listed groups, spurred on by the development of the concept of value creation, the end of the large conglomerates (General Electric plc, Saint-Gobain, ITT, etc.), and the succession of family businesses created in the immediate post-war period, provided a breeding ground for the development of this new form of private equity.

The long phase of falling interest rates and the correlative rise in valuation multiples (which favours financial performance), the renewed motivation of the managers of acquired divisions (often managed very loosely) through management packages, and the focus on cash and profitability, combined with the leverage effect of debt, explain the very high returns on investment that attract and retain investors. Over the years, the success of LBOs has been considerable, so much so that for many, private equity has become synonymous with LBO funds. From being a temporary lock between a family shareholder or a division of a group and the stock market or another group, LBOs have become a means of long-term ownership of companies with the development of secondary and tertiary LBOs, etc., such as Optven for example.

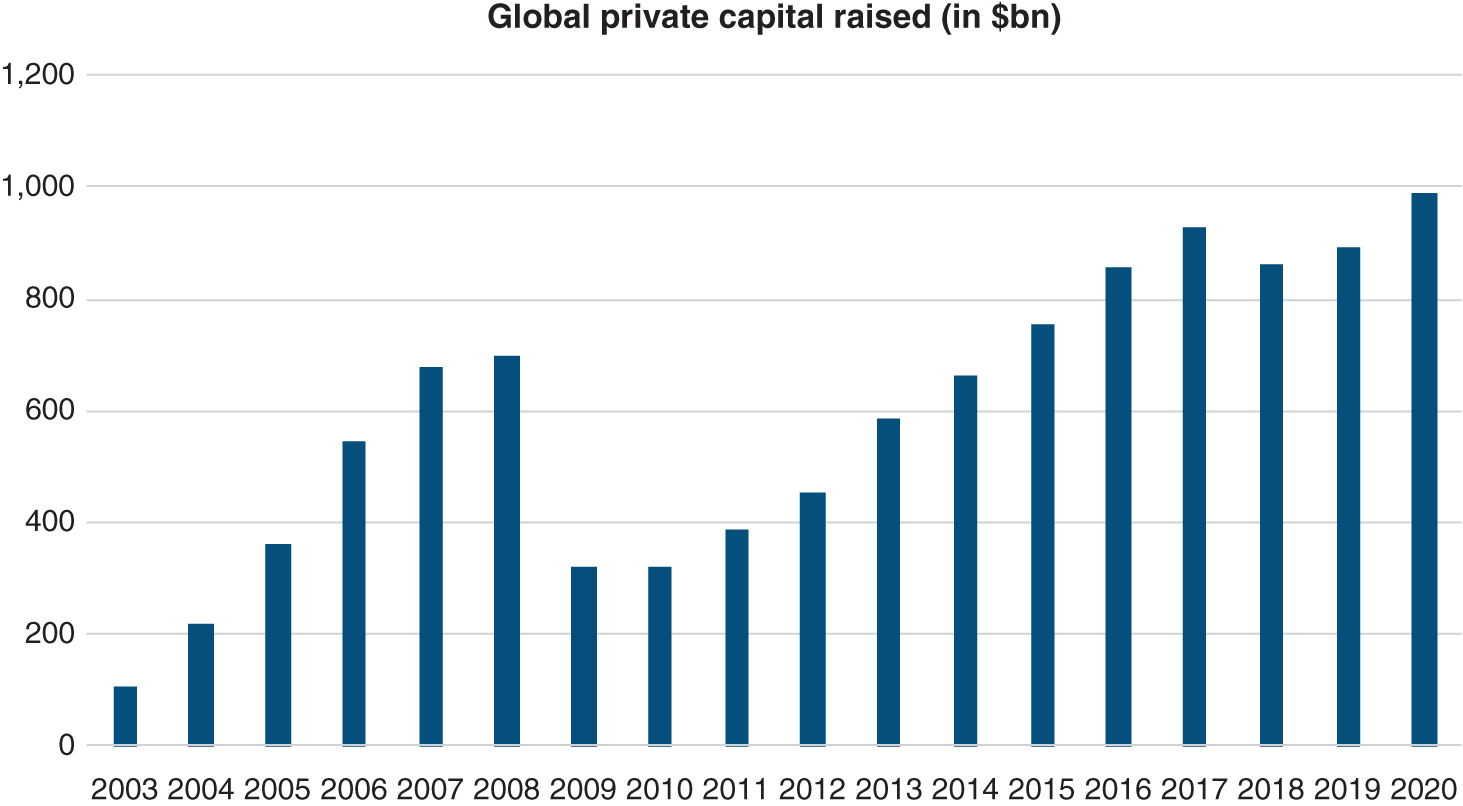

Buoyed by their success, some of the historical LBO funds (KKR, Blackstone, Apollo, Ardian, etc.) are expanding their activities to include investments in private debt, infrastructure, development capital, venture capital, real estate, distressed companies, natural resources, minority stakes in listed companies, etc. As a result, McKinsey estimates that in 2019 private equity, in its broadest sense, will manage $6,500bn, up 12% over 2018.

Although it has been growing since 2002 at twice the rate of world market capitalisation, and has multiplied its outstandings by more than seven since then, the unlisted market still represents only around 7% of world market capitalisation ($109,210bn at the end of 2020), compared with half as much in 2000.

Although this share may seem small, we no longer meet investors today who say they are not interested in private equity. On the contrary, most want to increase the proportion of their assets allocated to this type of investment, which has now become mainstream.

So much so that a number of major investors, sovereign wealth funds, family offices and pension funds have developed their own tools and structures for investing in the unlisted market in a traditional manner.

2/ THE GROWING COMPLEXITY OF LIFE ON THE STOCK MARKET

Market windows are periods when the stock market felt able to subscribe to capital increases or to welcome new recruits into its ranks. Outside those ranks, there was no salvation and the only thing to do was wait. Hence sometimes after a few months of preparing a financial transaction, it has to be cancelled on the eve of the launch! All this because a competitor's quarterly results are 2% below expectations and its share price has fallen 10–15%, or because a central bank has not announced the expected quarter-point drop in its refinancing rate. You have to have nerves of steel and have your plan B ready.

Most listed companies with a market capitalisation below €1bn are not covered by analysts or are only included in studies that paraphrase their publications. The rise of passive management4 (around 20% of assets under management in Europe and 45% in the United States), which simply duplicates an index without basing its investment choices on financial analysis, is the primary reason. The Mifid II Directive, which came into force in Europe in 2018, by seriously reducing the quantity, or even quality, of research published on listed companies, has reinforced this trend. The share of transactions taken by high-frequency trading (HFT), which can exceed 50% of volumes, increases the suspicion that prices are disconnected from companies' actual performance.

Source: Data from Company data, FactSet

While it seems to us to be completely unjustified to claim that stock markets are affected by short-termism, or that listed companies are affected by propagation of this defect,5 the fact remains that:

- Business life is often a succession of setbacks, of changes in strategy necessary for survival or of seizing opportunities. When you're listed, it's hard to escape a 10–20% drop in price in one day, which is not always justified. It's hard not to think that some people sell first and think later. While this decline will be corrected over time, managing the effect on employee morale is an extra task.

- Governance of listed companies has improved significantly over the years6 and is often of better quality than governance of family businesses, cooperatives or subsidiaries of groups. However, it is still often marked by complacency with independent directors chosen de facto and de jure by the majority shareholder or manager. There is not always sufficient debate and challenging of ideas. And poor governance sooner or later has consequences for the company's operations.

- There are fewer and fewer shareholders with whom the managers of listed companies can discuss strategy and figures, since some shareholders simply duplicate a stock market index and others often delegate to agencies the task of studying meeting resolutions.

- The stock market allows you to vote with your feet (by selling your securities) when you disagree with a strategy or with the execution thereof. But sometimes a manager or a team just has to be replaced and this often happens too late in the day when there aren't any strong voices on the board of directors or among the shareholders of a listed company.

- A listed company may find it difficult to take on debt beyond the levels accepted on the stock exchange (say more than 3 times EBITDA), and it may not always be the right time for the desired capital increase. In short, the “easy” financing that comes with being listed may be somewhat theoretical.

- To be listed is to be on a market and to be subject to its fluctuations (market risk), sometimes independently of a company's actual health.

3/ INVESTMENT FUNDS HAVE TAKEN CARE OF THEIR WEAK POINTS AND KEPT THEIR STRONG POINTS

In recent years, private equity funds have been working on their weak point: the illiquidity of their securities, which corresponds most closely to the maturity of their funds. This is a bit like squaring the circle, because how do you allow investors to exit a fund before it matures, while at the same time allowing the fund to have the time it needs to create value in its holdings by improving margins, digital transformation, acquisition and integration of competitors?

Faced with this need, unlisted funds have specialised in or have created funds specialising in secondary transactions (such as Ardian in Europe) to buy all or part of their shares from private equity investors before the normal maturity of the funds. This provides liquidity to those who need it, in amounts that are constantly increasing and that reached $87bn in 2020.

An investor in an unlisted fund can sell its shares in an LBO fund at a discount of less than 5% of the estimated value, about 10% for a fund invested in real estate and 15–20% for a venture capital fund with much more volatile assets. These levels are well below the discounts we see for listed conglomerates or investment companies.

At the same time, private equity funds have not let their guard down on their strong points:

- They continue to have their own mode of governance7 which constitutes a real competitive advantage. Unlike investors in listed companies, that hold very small minority stakes in scores (or even hundreds) of listed companies, whose managers they see only occasionally, private equity fund managers monitor only a few investments, which gives them a degree of understanding of these companies that facilitates intense and regular dialogue with their managers – fruitful discussions between informed people. The strategy is then better defined and controlled. In addition, management packages offered to the managers of the companies in which they invest, combine the carrot and the stick to align their interests with the progression of the company's value that they and their teams will create;

- They continue to offer risk-adjusted rates of return, after manager compensation, that are on average at least equal to those of listed investments, with the best of them well above. For example, the French private equity industry reports an average rate of return after costs of 11.2% per annum over the last 15 years, and 9.9% over 30 years (i.e. an 18.7-fold increase in value);

- They continue to be part of an average investment period of five years, which gives management time to implement a strategy, and if the horizon of the managers' business plans does not correspond to that of a private equity shareholder fund, it is not uncommon for the latter to sell its stake to another fund whose liquidation deadline falls after the end of the business plan.

4/ HOW DOES THE COMPANY POSITION ITSELF IN THIS MATCH BETWEEN LISTED AND UNLISTED COMPANIES?

Today, above a valuation range of around €10–15bn, only the stock market is likely to offer liquidity to investors who want to sell their shares. Admittedly, before 2008, LBOs were valued at around €30bn.8 But that was before 2008, although they will most certainly be back.

It will take some time before private equity funds have the financial means to take an interest in the giants of the stock market, worth more than €50bn or €100bn and which represent the bulk of market capitalisation in value terms. And even if they had these means, current conditions do not suggest significant value creation, with a few exceptions. Most of these groups are currently well managed and difficult to consolidate among themselves, given the antitrust problems involved.

With a valuation below €10–15bn, everything becomes possible again. As an illustration, in 2019, KKR bought the free float of the German media group Axel Springer to take it off the stock market in a transaction that values it at €6.8bn, i.e. 40% above the stock market price. The same controlling shareholder and the same managers are thus moving from listed to unlisted. This example is far from an isolated one as we also have Ahlsell, Wessanen, Merlin, etc.

Under what conditions could such a small company stay and prosper on the stock market? We see several:

- Run a simple, easily understandable business, with rated peers to facilitate comparisons and avoid discounts;

- Avoid carrying too much specific risk;

- Have a free float of at least 30 to 40%, because free float counts more on the stock market than market capitalisation;

- Have a story to tell investors (equity story), and tell it, whether it is one of growth like Cogelec, consolidation of a sector like Euronext, or dividend yield like Pearson;

- Seek out several funds and favour a fragmented shareholding structure (the Stock Exchange) in order to remain in charge of your own house, rather than one fund investment, even a minority one, which leads to a certain amount of shared control.

Otherwise, we believe there is a high risk of a discounted valuation, which is not a short- or medium-term problem if control is retained and if there is no need for financing. Given the growing size of asset managers on the stock exchange, the largest of them (Blackrock) manages $7,300bn and the largest European (Amundi) €1,790bn, liquidity is concentrated on large caps with small and mid-caps being neglected. For the latter, valuation multiples are often significantly lower than for large stocks and the required rates of return are higher in view of a growing liquidity premium.9

At the same time, the regulatory constraints of listing are increasing without the cost/benefits balance tilting significantly towards the latter: IFRS standards on turnover and rentals, the MAR Directive, internal insider listings, etc. The aim is to protect investors, specifically private individuals, who are less and less frequently direct shareholders of listed companies (one third of listed companies' shareholders in the United States, around 10% in France). You have to be really motivated to stay listed when you're a small or medium-sized company, and you are not likely to carry out an ICO,10 where, in order to attract buyers, the regulatory environment is very light, although not very consistent with the rest!

5/ IN THE END, A POROUS BORDER BETWEEN THE LISTED AND THE UNLISTED

We believe that listed and unlisted companies will continue to coexist in a complementary fashion, with private equity increasing its dominance in the segment up to around €10bn in value, and listed investment prevailing beyond that.

The boundary between these two modes of shareholding and governance is porous and we see a lot of toing and froing. Private equity firms have no qualms about selling companies on the stock market for which they no longer see any significant value-creation potential, especially if the stock market then generously values the companies, or those whose size is testing their limits. But private equity can also have its funds listed on the stock market and even hope one day to have them listed at a discount equal to or lower than that offered by secondary funds. A large listed investment fund controlling SMEs and second tier companies probably makes more sense to investors, and some companies, than a direct listing of the latter.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISE

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

- 1 See Section 45.3.

- 2 Enron's and Lehman's employees can confirm this!

- 3 See Section 46.2.

- 4 See Section 18.9.

- 5 See, for example, Kaplan (2018).

- 6 See Chapter 43.

- 7 See Section 47.3.

- 8 See Section 47.2.

- 9 See Section 19.4.

- 10 See Section 25.3.