CHAPTER 2

GETTING STARTED

As a self-taught artist whose career began accidentally on an otherwise unremarkable subway ride, I consider myself a bit of an expert on the matter of beginnings.

It’s a cliché, but starting is the hardest part of any new endeavor. There can be a surprisingly long distance between having a sketchbook and drawing in it. So instead of going straight from talking about supplies to how to use them, I thought we should take an important detour and talk about how to start getting started.

I don’t know how. I’m not good at it. We find lots of reasons to stop ourselves before we ever get a chance to start. But if you start with assumption that you have talent, there is every reason to begin. Your point of view, your heart, your mind, your ideas—those are the talent. Once you understand this, you won’t confuse your current ability level with your inherent talent. If you keep seeking to express yourself, your talent will manifest as skill. After a few weeks of drawing on the subway, I was hooked. I would step on the train, reach for my sketchbook, uncap my pen, and let my eyes wander over the crowd. It was my favorite part of the day. But things soon changed from pure joy to a mix of emotions. I loved how I felt while drawing, but when I stopped to look at what I had drawn, I didn’t feel so great. I thought the only worthwhile way to re-create the world was to do it with perfect fidelity, and I was disappointed in my wobbly lines and scratchy sketches. One day I had an epiphany, which prompted me to say to myself: You were an art history major, right? So, you know art isn’t about perfectly re-creating what you see. We celebrate Da Vinci, Picasso, and Van Gogh because they re-created the world as they saw it. If you do the same, aren’t you following in the footsteps of the greatest artists? From that moment on, I decided that maybe I was the next Picasso. Instead of stopping, I started focusing on expressing a view of the world as I saw it. Draw what you see and feel, and your own style will naturally develop. You might not be the next Picasso (or maybe you are!), but what’s the worst that could happen if you treat your efforts—and yourself—as if you are?Start with the Right Mindset

Sure, you’re not Picasso. But then again, maybe you are.

Now that I’ve convinced you to bring yourself fully into your creative endeavors, we should talk about the uninvited guest who will tag along: your inner critic. This is the voice that tells you to stop having fun and that everything you do is dumb, or bad, or not good enough. That inner critic can be cruel and callous. Although I’d decided I might be Picasso, my inner critic was not convinced. It would say, “You’re so bad at this! OMG, that doesn’t even look like the person you’re drawing!” Instead of giving in to its taunts, I made a vow that when my inner critic acted up, I would talk to it like a naughty child, and simply tell it: “If you can’t behave, then we can’t draw today. I’m going to close the sketchbook, and you’ll have to find something else to do.” I suggest you do this when that voice gets too loud. Kindly tell it to zip it. If that doesn’t work, perhaps agree that today is not a good day to push. Your creativity is a precious thing. Don’t let anyone, let alone yourself, contaminate the joy it can bring. There’s always tomorrow to try again, and again, and again. Is this a bunch of mistakes or a brief lesson in how to draw a pair of heels? Though my inner critic tried to silence me, I didn’t let early attempts like these go unappreciated.Silence Your Inner Critic

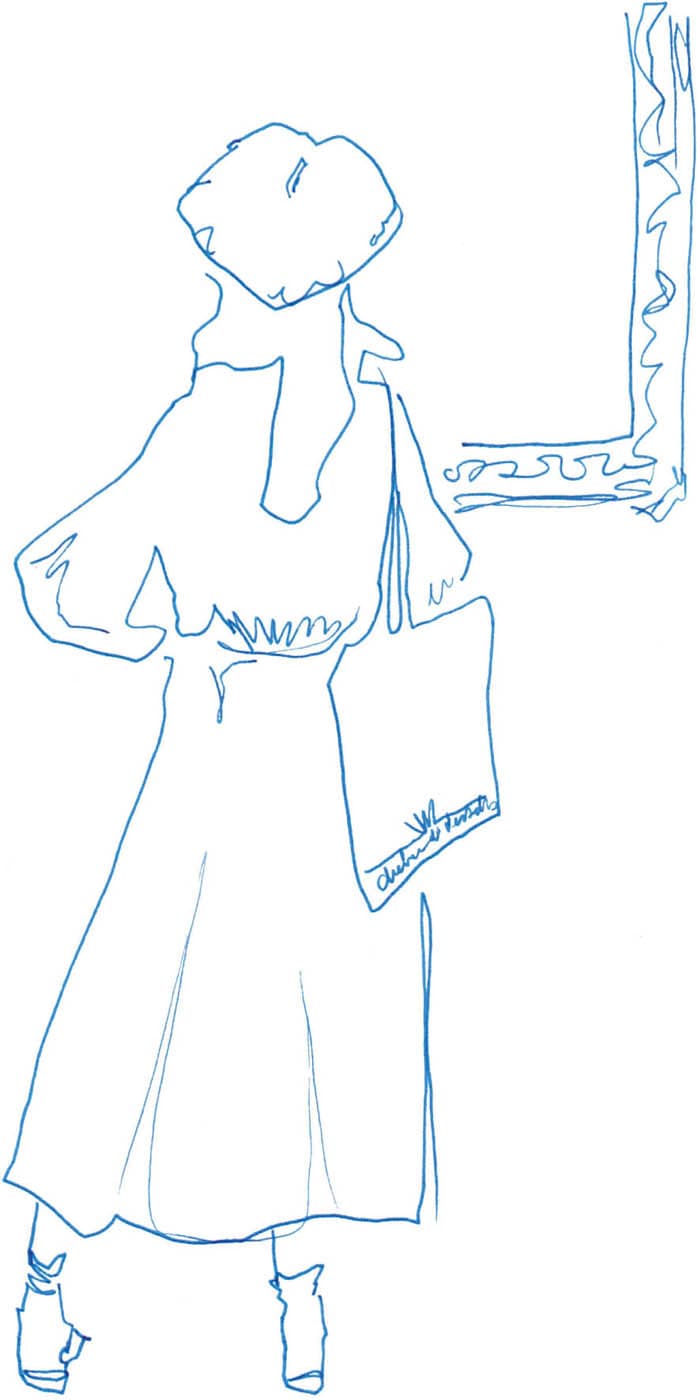

Don’t worry about what will happen if you make mistakes—plan on making them. I’ve certainly made plenty of my own. Your mistakes are opportunities for discovery and innovation. I’m on the C train in New York City and she is sitting across from me on a crowded morning train. Her hair is cut into a sleek bob that frames her face with angular precision. Though only half-awake, I have managed to capture this elegance in a few simple lines. I look at my drawing; just one more line and it will be perfect. I touch my pen to the page and then watch as it suddenly veers off course, leaving a jagged trail of ink in its wake. I have been bumped. The woman next to me, in settling into her seat, bumped my arm and ruined what I have appraised to be the single greatest drawing I have ever made in my life, or at least this week. I want to cry. I don’t have time to start over, and I don’t want to. How can I fix this? I take my pen and place it on that jagged, imperfect line and follow its path; and then I draw another line, just like it; and then another and another, until instead of a single, elegant stroke, there is an eclectic tangle of little lines defining my muse’s perfect coif. I had a different drawing than I had planned, but one that I liked much better. I started using this technique to draw hair whenever I could and looked for any opportunity to draw patterns and stripes with lines that took their own imperfect route across the page. Don’t worry about what will happen if you make mistakes—plan on making them. I’ve certainly made plenty. Your mistakes are opportunities for discovery and innovation. Don’t scratch or tear out the drawings that don’t work. Let them exist as a record of your progress—a series of lessons in the form of mistakes. The more you fail, the more you’ll realize that mistakes are instructional, not fatal.Embrace Your Mistakes

My first career was as a professional opera singer. When I told people what I did, the most common response was, “Oh, I can’t sing at all!” To which I would reply, “If you are physically capable of making sound, then you can sing. How good you are doesn’t matter, if you’re enjoying yourself.” It’s important to uncouple the product from the process and redefine what good art is. Making art feels good, so enjoy it. The process of turning your world into art has some real benefits. It’s okay to be impressed with yourself. In fact, it’s important. Shift to a mindset of wonder: appreciate what you’re doing and evaluate your work by joy, not excellence. Does it make you happy? Ask yourself that question instead of, “Is it good?” Even if you don’t love the final product, if you enjoy the process of its creation, you won’t walk away empty handed. I love this little seagull hunting at the shore. It may be a little rough, but when I see it, I remember that lovely day at the beach.Follow the Joy

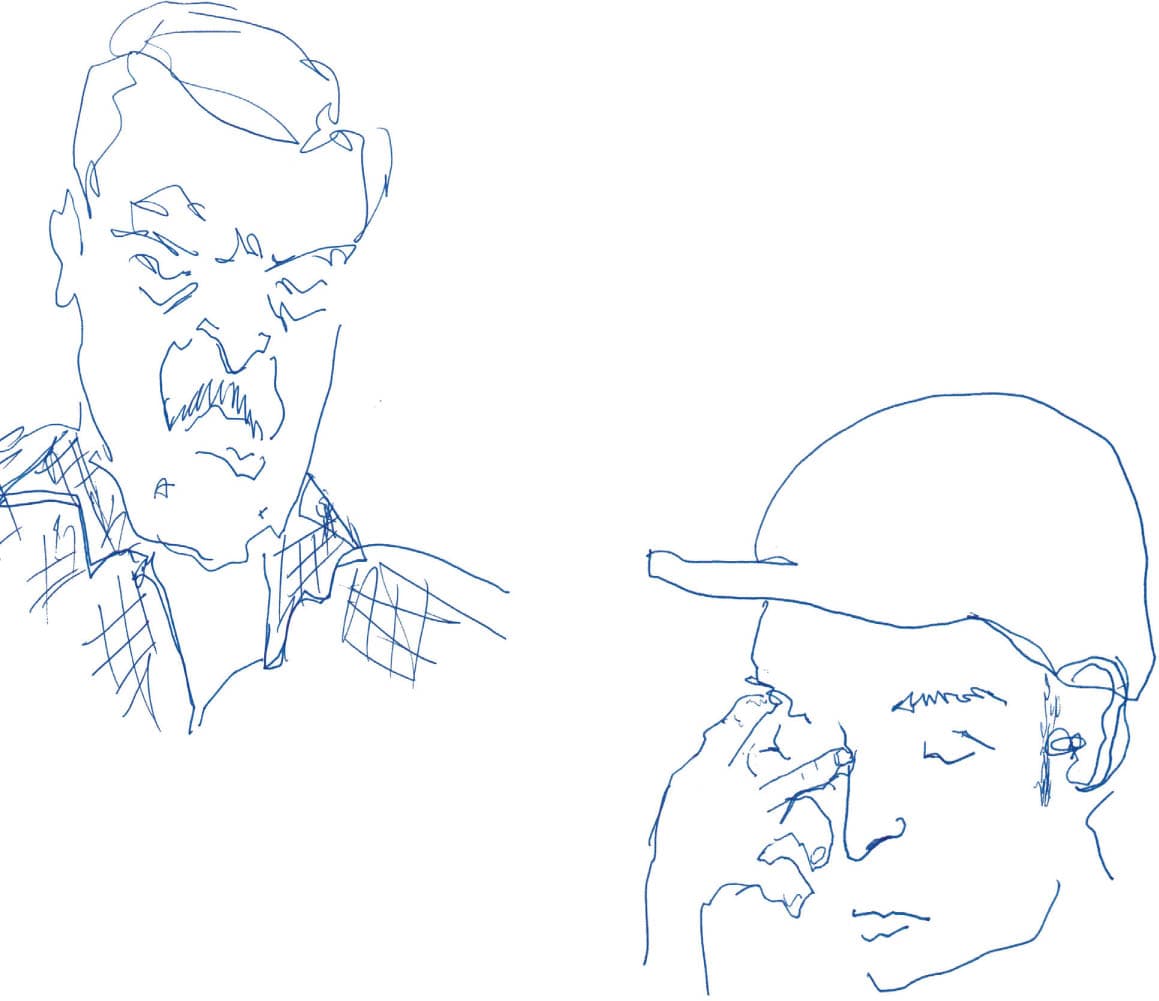

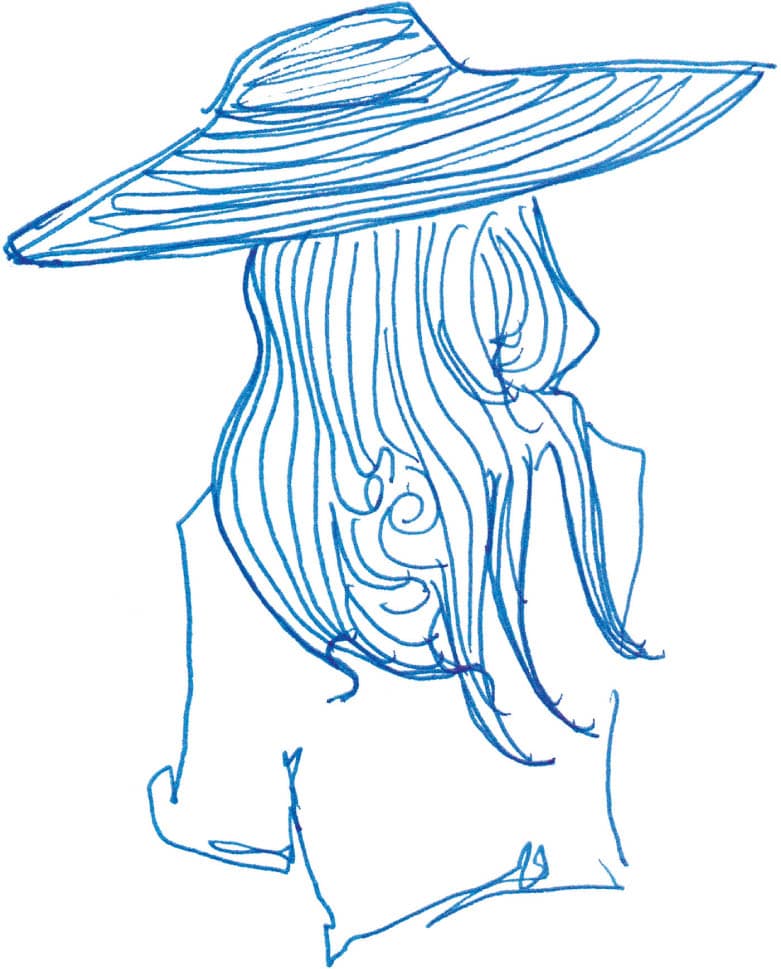

The joy of observational drawing is that it transforms everyday moments into something more. A walk through the park, a trip to the bank, or sitting in your house become something worth remembering and worth documenting. But, this transformation doesn’t happen unless you learn to see the stories hidden in plain sight. When I first began drawing from life, I thought I was just drawing the things that caught my eye. But I soon realized that I was doing more than that—I was telling a story. As a visual storyteller, sometimes you’ll know the story—like when you draw your favorite mug—and sometimes you’ll have to imagine it, like drawing the stranger sitting next to you at lunch. There are a million stories being told in any given moment. Your job is to listen with your eyes and tell those stories using lines of ink. Curiosity is key to finding and telling good stories. Curiosity breeds empathy, and empathy is how we imagine the lives and stories happening outside of our own. Overlook the obvious and bring the background into the foreground: the cactus that’s moved with you to every new home or the barista at your local coffee shop—these are stories waiting to be told. Look for small details that suggest a bigger story. In writing, this is called synecdoche, when a part is used to represent the whole, like calling a businessman a suit. This concept works just as well when you’re drawing. Notice how your emotions affect the stories and details you’re drawn to. When you’re feeling sad, you might draw the tree outside your window because of the way its branches droop. On a happier day, you might draw the same tree, focusing instead on the cheerful squirrel resting in those same branches. A pile of shoes in the front hall embodies the joyful chaos of family life. A few fish could represent a busy fish market. A couple’s clasped hands tell an entire love story. Funky socks paired with fancy oxfords could speak to a high-powered “suit” with a sense of humor. Iris, as I like to call her, is one of my favorite people I’ve never met. I saw her one night, sitting in a French café on the Upper East Side. She was eating alone at a table for two, facing into the restaurant so she could watch the comings and goings of waiters and patrons alike. We briefly locked eyes as I scanned the restaurant. I, too, was dining alone, and instead of catching my own reflection in the mirrored wall, I saw Iris seated across from me. She was striking: gray hair piled high on top of her head and giant glasses taking up most of her delicate and slightly dour face. At first glance, she could have been dismissed as a sort of sad and perhaps lonely woman, but upon closer inspection, there was a tiny curl at the edge of her lips, a secret satisfied smile. I noticed the collection of beaded necklaces strung around her neck and wondered if she had collected them on exotic travels to visit faraway lovers. A few wisps of hair escaped from her careful updo. I imagined her swiping at them distractedly as she cooed to pastel colored parakeets that surely lived with her in a giant apartment filled with art, books, and secrets. Everyone who sees my drawing of Iris has a strong response to her. I tried to capture the details about her, both obvious and subtle, that communicate who she is—or who she might be. Sometimes a story is as simple as sharing a feeling, and your drawing becomes a short story where the viewer reads between the lines to find the meaning. It was late spring, and New York City blooms like a flower. Apartment windows are thrown open like blossoming buds and spring wardrobes are paraded on the streets. Ankles are exposed for the first time in months, and sturdy boots are replaced with kitten heels and stilettos. On a particularly beautiful evening, I met up with a friend for dinner outside and I noticed the woman next to me. She was sitting on a high bar stool, her legs crossed at the knees and a leopard print slingback shoe balanced precariously on the end of her toe. Above the table, she had one hand wrapped around a wine glass and the other one tucked under her chin as she leaned closer to her date. The moment was both precarious and sure, relaxed and engaged—a joyful, frivolous, flirtatious shoe that might drop at any moment. I could have drawn the whole scene, but the sensation of it was totally expressed by the casual way she crossed her legs and her stylish, playful shoes. I know that each viewer will see this drawing differently, but I think they’ll find something familiar in what this small detail evokes. Each of your drawings contains three stories: your story, the story created by the viewer, and the story of the subject. A perfect example is this drawing of a fashionable lady zipping along on a scooter, made while I was on vacation in Paris. My Story: This is my memory of sitting in a café, sipping cappuccinos and eating croissants, and watching Paris pass by. This chic woman, with her tiny purse, tall heels, and fancy dress, was quintessentially Parisian and a distillation of my experience in that moment. The Viewer’s Story: Because I didn’t draw the details of the city street, the viewer might imagine another story altogether. Perhaps it’s about the most fashionable person in Paris, Idaho. Perhaps it’s about themselves riding down the street, feeling the wind and the sun. The Story of your Subject: There is the real story of this Parisian woman, which we may never know, but upon which we can expand and imagine forever. These three stories form an important relationship with you at the center. The drawings you make become the stories you tell about your own world. No one else can do that better than you.Becoming a Visual Storyteller

Find the Extraordinary in the Everyday

Visual Storytelling in Action

One Drawing, Three Stories