Chapter 6 Business Intelligence in the Broader Information Technology Context

“In the last 15 years, a litany of IT-enabled initiatives, from business process reengineering to enterprise resource planning, have elevated the importance of investing strategically in IT…. But while opportunities seem boundless, the resources required by these investments—capital, IT expertise, management focus, and capacity for change—are severely limited.”

—Jeanne W. Ross and Cynthia M. Beath, “Beyond the Business Case: Strategic IT Investment”

Business intelligence (BI) initiatives take place in company-specific business contexts where they must compete with other information technology (IT) projects for resources. BI is downstream from day-to-day transactional systems and enterprise applications, and as a result, BI initiatives often must work within technical decisions that have already been made. Finally, BI is affected by a company’s IT strategy and IT operating policies. These and related factors affect what BI can accomplish, how long it takes, how much risk it poses, how much reward it offers, and how much it costs.

6.1 Where Business Intelligence Fits in the Information Technology Portfolio

The mission of IT is to support the business. Although this is simple in concept, it is complicated in practice: supporting the business can mean many different things. Support can mean relatively straightforward activities, such as providing and managing Internet access for the company, and highly complex endeavors, such a migrating a global corporation to a common enterprise requirements planning (ERP) system. The latter often entails substantial changes to existing business processes or substantial customization of the packaged ERP software application—both of which have serious risks and life-cycle cost implications.

For the modern company of any size, managing IT amounts to making a series of investment decisions (bets) about technologies, productivity improvement, and, ultimately, profit and business performance. To complicate matters, many business executives in large companies are not well versed in IT. Although an effective chief information officer (CIO) can help, these business executives are called on to make multi-million dollar investment decisions that have substantial risks and substantial impacts on the business capabilities of the firm. Also, IT and business executives often speak different languages. IT concepts that have a very specific meaning to IT people often have little resonance for business people and vice versa. Figure 6-1 illustrates this language gap.

FIGURE 6-1 The modern Tower of Babel: information technology and business managers can’t communicate.

In the face of such complexity and risk, leading companies have adapted portfolio management techniques to the task of managing IT. The IT portfolio can be thought of as all the IT needed to support the business. It can range from basic infrastructure, such as networks and computers, to transactional systems, such as point-of-sales terminals and ERP systems, and finally to BI systems. A depiction of the IT portfolio is shown as Figure 6-2, which is adapted from an excellent book on IT strategy written by Peter Weill and Marianne Broadbent (1998) called Leveraging the New Infrastructure: How Market Leaders Capitalize on Information Technology.

The foundation of the IT portfolio is infrastructure, which can be thought of as a utility that promotes a company’s ability to leverage IT. The utility provides many of its services as shared services, which is both a cost-optimization strategy for an agreed-upon level of service and a way to ensure that all the foundational elements of the infrastructure work together. A familiar example of this approach is the plumbing and wiring of a house, in which we want all the pipes to fit together and all the wires to support standard appliances.

FIGURE 6-2 Structure of the corporate information technology portfolio (adapted from Weill and Broadbent, 1998).

The next layer of the IT portfolio is composed of transactional applications (transactional IT) that allow the company to conduct its day-to-day business. Transactional IT has evolved from “home-grown” custom-developed software to packaged, standardized applications that tackle various aspects of the business. These aspects include sales force management, customer interactions, order processing, inventory management, supply chain management, purchasing, warehouse management, manufacturing execution, and financial reporting. The general motivation for investments in transactional IT is operational efficiency and effectiveness, although in some cases having stronger transactional IT capabilities can confer a “first mover” advantage. Two companies that reaped this advantage are Dell and Cisco, whose transactional IT systems integrated their entire supply chains and allowed them to offer differentiated customer service combined with lower prices.

The top layer of the IT portfolio consists of strategic applications and informational applications. Strategic applications result in competitive advantage to first movers and early adopters. The classic example is revenue optimization applications developed in high fixed-asset businesses such as the commercial aviation and hotel industries. The combination of computing power and complex operations-research models allowed early movers to dynamically balance supply and demand by adjusting prices to fill airline seats and hotel rooms instead of leaving them vacant. Done well, BI has the potential to deliver strategic applications.

Informational applications, in contrast, aim to provide business leaders and managers with the information they need to effectively address strategic, tactical, and operational business challenges. In our view, this part of the IT portfolio is populated by a wide range of tools and techniques, including the following:

Tip

It bears repeating that better analytical tools by themselves won’t make BI pay off for an organization. The organization must also be ready to restructure and adapt its processes to take advantage of new BI capabilities.

In practice, companies use IT in a lot of different ways to provide useful information. In fact, it’s reasonable to say that information usage at many companies is ad hoc and idiosyncratic, which corresponds to level 1 in the BI maturity model discussed in Chapter 5. BI methods and tools exist to bring order, efficiency, and consistency to informational IT so that companies can manage their affairs with a single version of the facts. Further, BI can do more than just make information available. By providing better analytical tools and more structured, information-rich decision processes within core business processes, BI can improve profits.

In addition to its role in informational and strategic applications, BI methods and tools are also being used to enhance transactional applications. The classic example of this is the way that Amazon.com uses transactional history, data warehousing (DW), data mining, and BI to display individualized recommendations of additional items a shopper might wish to purchase. Other potentially fertile uses of BI methods and tools in operational contexts can be found in manufacturing, customer service, and order fulfillment contexts, in which highly profitable customers can be given preferential treatment based on business rules and access to transactional history and customer lifetime value calculations.

As just one of the types of potential IT investment within the IT portfolio, albeit an increasingly important type, BI investment opportunities are affected by each company’s IT strategy and IT budget. IT strategy can be thought of as the set of choices a company has made around such key questions as:

Based on the answers to these and related business questions, a company can then set about determining its IT budget, which includes capital and operating budgets.

Establishing Your IT Budget

Establishing an IT budget is like establishing any budget: it involves both art and science. One common approach is to compare your company to industry “norms,” which are after-the-fact reports that present statistics about a survey population. For example, some data we’ve seen suggest that manufacturing firms spend an average of 1% of their revenues on IT. The problems with this approach are twofold. First, it assumes the companies in the survey know what they are doing—a tricky assumption. Second, it doesn’t provide much insight into how the money was invested. On a more theoretical level, economists would argue that the firm should invest in every IT project that offers a return on investment (ROI) that exceeds the firm’s cost of capital. The problem with that approach is that the ROI calculations for IT projects are sometimes difficult and intertwined with other projects. Because of the problems with these approaches, we think it’s better to determine what IT capabilities your company needs to support its business strategies, develop bottom-up budgets, and then compare the results to available funding, however that gets determined in your company.

Coming to BI investment, we see that BI initiatives must compete with other IT investment opportunities for funding, and this often entails navigating the IT capital budgeting process. Whether the BI initiative is at the functional, business unit, or enterprise level, it must typically develop a business case, ROI analysis, cost-benefit analysis, or similar document. The specific requirements depend on company policies, and the mechanics are beyond the intent of this book. For an incisive analysis of the challenges of discounted cash flow analysis, you may wish to consult Chapter 3 of Dynamic Manufacturing (Hayes et al., 1988). To understand some of the organizational dynamics associated with capital budget requests, you may wish to consult Chapter 3 of The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning (Mintzberg, 1994).

That said, the basic business case for any potential BI investment is profit improvement and (especially for government agencies and nonprofits) more cost-effective achievement of the organization’s mission. The specifics for any organization can be developed via BI opportunity analysis (see Chapter 2) and the architectures phase analyses (see Chapter 4).

Tip

BI initiatives must compete with other IT initiatives for funding. To increase the odds of obtaining funding, it is important to understand your organization’s IT strategy and IT budget. In this way you can tailor your positioning of BI initiatives to ensure funding.

By using the results of those analyses, we can develop a cogent description of how BI would be used to improve profits and what business process changes would be involved. We can discuss risks and rewards with some level of empirical rigor, and depending on how much cost analysis has been done, we may be able to define the level of investment required at a reasonable level of specificity. Whether we are developing the business case for BI-driven profit improvement as an enterprise initiative, for a BI portfolio for a business unit, or for an individual BI investment, a reasonable amount of structured analysis will leave us in a good position to discuss the business benefits (business value capture mechanism) and the order of magnitude of costs that must be incurred to achieve those benefits.

6.2 Information Technology Assets Required for Business Intelligence

The composition and scope of IT assets required for BI depends on your company’s BI strategy. Informational applications can be—and are—implemented with desktop software such as Microsoft Excel and Access, often creating dozens if not hundreds of so-called “analytical silos.” This approach has been shown to create different views of what should be the same business information, thus undermining confidence in the information delivered. The proliferation of analytical silos is often one reason that departmental, business unit, and/or enterprise BI initiatives are initially launched. For our purposes, we will assume that your company is planning an enterprise BI-driven profit improvement program.

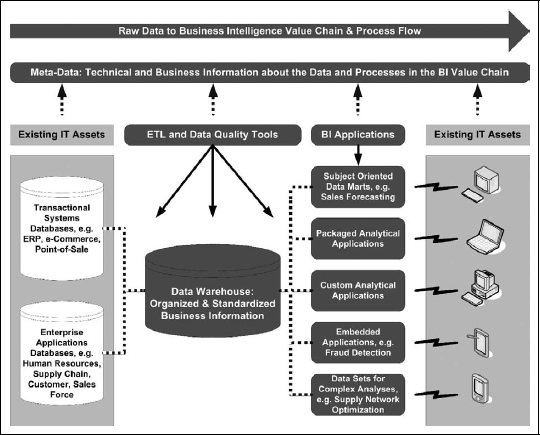

From a business perspective, a typical BI environment consists of the elements shown in Figure 6-3.

When many executives, managers, and knowledge workers think of IT in general, they think in terms of what they can see and do with their computers and PDAs, and what they receive from others in the form of reports, memos, and e-mails. Although some power users can be quite deep in their understanding of data and databases, most users have a strictly utilitarian view of IT. Thus, to them, BI is just another name in the IT alphabet soup. What counts is what BI can help them see and do.

FIGURE 6-3 Elements of a typical business intelligence environment.

Because of this orientation and because of the magnitude and importance of the BI investment decisions that need to be made, it’s important for business leaders and managers to expand their understanding of the scope and configuration of IT assets required to support a BI-driven profit improvement initiative. In saying this, we recognize that some business leaders and managers already have a good working understanding of this topic. In our experience, however, we have seen many cases in which it is tough sledding to get the IT assets that BI requires.

6.2.1 The Basic Scope and Configuration of Information Technology Assets for Business Intelligence

In Chapter 4, we discussed the fact that there are mixed-use BI environments and dedicated BI environments in use at major companies in a variety of industries. Although distinct operational impacts are associated with one approach or another, about which we will have more to say in Section 6.3, from a business perspective, the IT assets in play are the same. Accordingly, we will set aside that distinction for purposes of this section.

From a systems engineering perspective, creating a BI asset is a systems integration task wherein we add special-purpose BI tools into an existing IT technical infrastructure and we create specialized IT processes to move data along a value chain while preparing it for its intended business uses. For example, we might take raw transactional data from several of the thousands of data stores within an ERP system, combine it with raw data from a sales force management application, organize it by business unit and geographic region, summarize it at various levels of the organizational hierarchy, and push it into a special purpose data store used by business users for sales and operations planning. A generic (typical) IT technical infrastructure to support BI-driven profit improvement is shown in Figure 6-4.

Figure 6-4 highlights the BI assets and BI processes within the IT infrastructure, which is simplified for sake of discussion. In a typical company environment, transactional applications and other enterprise applications (in the “existing IT assets” box on the left) create databases. These databases and the associated applications are designed to present business information to business users via a variety of devices (in the “existing IT assets” box on the right), including PDAs, tablet computers, workstations, laptops, and terminals. The information presented can be seen on the devices and/or it can be printed out as standard reports. Most of the information presented is about the current state of the business for the current fiscal year, and that information is not organized to meet the complex requirements that BI addresses.

FIGURE 6-4 A typical technical infrastructure for business intelligence.

To meet the requirements for enterprise level BI-driven profit improvement programs, we introduce the BI assets and processes shown in the middle and at the top of the figure, with dotted lines to represent data flows and processes. Moving from left to right, we see that data contained in transactional and enterprise applications databases is moved into a data warehouse, which is a special-purpose database designed to meet BI requirements. Here, the raw information is organized and standardized to create the so-called “single version of the truth” for the various BI uses. This is also where we build subsets of business information that can be used by multiple BI applications. For example, the sales organization and the operations organization in many companies have a common need for business information about product or service sales—often by time period, by region, by product family or service type, by customer, and by other variables of interest. Given this common need, a single subset of business information can be prepared in the data warehouse for use by, for example, a packaged sales forecasting application for the sales organization and a customized sales and operations planning application for the operations organization.

Based on BI opportunity analysis and detailed BI requirements (see Chapters 2 and 4), data from the data warehouse is moved into BI applications (boxes in the middle-right of Figure 6-4), which we can think of as a combination of business information and one or more defined analytical approaches to gaining knowledge or insight from that information. Figure 6-4 shows some examples of BI applications, including the following:

The above list of representative BI applications should not be viewed as exhaustive or as the only way to characterize various types of BI applications. Rather, it is intended to show that BI-driven profit improvement at the enterprise level is likely to require a variety of BI applications to improve the specific business processes that impact profit.

To enable the basic flow of business information within the BI asset, as discussed above, we need to enhance existing IT assets with special-purpose BI tools and processes. One key toolset consists of extract, transformation, and loading (ETL) tools and data quality tools, shown in a box in the upper-middle section of Figure 6-4.

Data quality tools can ensure that the quality of data feeding into the data warehouse and BI applications is appropriate for the intended BI application. It is not uncommon for transactional systems and enterprise applications to contain erroneous or incomplete data, which is fundamentally a business problem as business users are the people who enter the data into such systems in the first place. The key from a BI perspective is to understand the nature and frequency of data quality issues in order to determine whether the issues are material to the usability and credibility of the business information bound for the data warehouse and BI applications.

ETL tools are central to first-rate BI environments. They are mature tools that reduce development time, manage the flow of data along the BI value chain, and provide the means to manage changes to data over time as transactional systems and enterprise applications evolve. One key component of an ETL tool and other tools used to develop BI environments is a meta-data repository: a database that contains information about the business information in the data warehouse and BI applications and the IT processes that move the data along the BI value chain. Figure 6-4 shows the flow (in dotted arrows) from the various databases and processes in the environment into the meta-data repository environment (a box that extends across the top of the drawing).

To illustrate the role of meta-data, consider a simple example in which a transactional system such as ERP uses a month-day-year convention for dates and an enterprise application such as a human resources information system (HRIS) uses a year-month-day convention. For the BI asset to present date-related information in a consistent way, data from one or the other of these two sources must be changed to match the desired convention. The meta-data repository keeps track of data formats in the various feeder systems, keeps track of what changes are made to the data, maintains business rules for how business information is to be aggregated for higher-level presentation, keeps track of how often data must be updated, and performs a host of other tasks associated with being able to produce reliable, credible, and useful business information on a repeatable basis.

This subsection has concentrated on what IT assets are required for BI and the basic roles for those assets. In the following subsection, we will provide a high-level overview of the key IT products that are required for an effective BI environment. This is meant as a guide for business leaders and managers. A plethora of technical IT information is available about these products for IT professionals involved in selecting or tuning specific products, and it is not our intent to rehash that information here.

6.2.2 Key Information Technology Products for Business Intelligence

Although we acknowledge that many technology investments are made by companies to support BI initiatives, including data profiling tools, metadata repositories, and DW monitoring software, we have intentionally limited the discussion in this section to the products that we believe represent the core BI technology investments that organizations make.

Database Management Systems

Referring again to Figure 6-4, we see that databases are core to BI. Moving along the BI value chain (from left to right in the drawing), data is extracted from one or more databases. It’s then placed in the data warehouse, which is a specialized database. Ultimately, it’s moved into BI applications, which provide a way to store and analyze the data. Each database has a different job for which it is optimized.

The foundational IT product that allows us to create, manage, and optimize these databases is the modern relational database management system (RDBMS). From the early 1980s when RDBMSs first emerged as commercial software products, the field has narrowed from dozens of players to a handful of dominant products. We have no commercial relationships with any IT product vendors, and it is not an endorsement of any particular product for any particular situation when we state that IBM, Oracle, Sybase, and SQL Server dominate the RDBMS market. Teradata, a proprietary database management system, is also widely used in the industry. All of these products are very mature. Their vendors continue to add functionality that makes developing, deploying, and managing data warehouses, data marts, and BI applications more efficient.

Ironically, the very flexibility of RDBMSs, combined with the high cost for enterprise uses, creates a common business and IT challenge for BI. Specifically, companies wish to leverage their investment in RDBMSs across as many IT uses as possible, including BI uses. Therefore, this key technology product is often managed as a shared service to support transactional systems, enterprise applications, and BI applications. This can create business problems associated with cost allocation and chargeback among projects, as well as create suboptimization problems that can impact IT operations, BI development and operations, or both. We will discuss these issues in the section 6.4.4.

Extract, Transformation, and Loading Tools

As we noted earlier, ETL tools are central to a first-rate BI environment. They are key for developer productivity, for data movement efficiency and throughput, for configuration management, for job scheduling, and for managing change over time. Similar to RDBMS products, ETL products are mature and low risk. Without endorsing any particular product for any particular environment, our market research conducted on behalf of clients in a range of industries confirms that the most mature general purpose products are offered by Ab Initio Software, IBM, and Informatica. Our research evaluated eight major areas for more than 20 vendors, including the following:

Tip

Because ETL tools are typically a large investment, you must understand the key features and functions that are needed to support your BI environment before making this investment. The BI program plan is a good place to get the “big picture” regarding the types of BI requirements that will need to be supported by the chosen BI technology.

Our research also confirmed that many excellent special-purpose products deliver one or more of the types of functionality listed above. Depending on your company’s specific requirements, for example, a specialized data profiling or data movement tool might be needed to complement a more general-purpose ETL tool. As with many IT products, there is often a trade-off between products that do many things reasonably well and products that do one thing extremely well. As always, the trade-offs need to be made factors. Also, when choosing products from niche vendors, whether they are small generalists or specialists, it is important to evaluate product strategies and the financial stability of the company because these speak to product business viability during the useful life of your investment. That affects ongoing vendor support for the product or products you may be considering.

Business Intelligence Platforms and Analytical Applications

On the right side of Figure 6-4, we showed five generic examples of BI applications. Some of the examples represent customized BI applications, which tend to be designed, developed, and implemented using standard commercial products that can be thought of as BI “platforms.” In the IT world, a platform provides a set of IT functional capabilities that in themselves do not solve a particular business challenge. Instead, the platform provides an integrated suite of IT tools that can be used to design, develop, and implement a customized IT capability that supports the business. BI platforms are specialized to address the specific tasks associated with delivering customized BI applications.

Market research conducted by a range of third parties suggests that the leading BI platform vendors include Business Objects, Cognos, Hyperion, MicroStrategy, and MicroSoft. Each of these BI platforms offers comparable functionality, although differences in product technical approaches make the different platforms more or less suitable for specific BI environments, depending on the range and type of BI applications that must be delivered. For example, some of the platforms are better suited for large number-crunching BI applications than are competing products. Given these factors, it is important to have a clear BI strategy in mind when selecting a BI platform.

Table 6-1

Analytical application vendors and product types

| Packaged Analytical Applications Vendors | |

| Enterprise resource planning (ERP) vendors, e.g., Oracle, SAP, Great Plains Enterprise applications vendors, e.g., Seibel, Deltek, i2, Lawson Business intelligence (BI) platform vendors, e.g., Business Objects, Cognos, Hyperion, Microstrategy, MicroSoft Niche specialists, e.g., CorVu, Geac, Pilot, Silvon |

|

| Packaged Analytical Application Product Types | |

| Budgeting | Human resources/workforce analysis |

| Planning | IT systems performance analysis |

| Forecasting | Manufacturing and quality analysis |

| Accounts payable analysis | Supply chain performance analysis |

| Accounts receivable analysis | Balanced scorecards |

| Cost analysis | Dashboards |

| Activity-basedcosting/management | Customer relationship management analysis |

| General ledger analysis | Sales force management analysis |

Figure 6-4 also shows a category of BI application called “packaged analytical applications.” By “packaged,” we mean commercially available software products, sometimes referred to as “shrink-wrapped” software. Many different types of packaged analytical applications are available, and they are sold by various types of software vendors (see Table 6-1).

At this point in the evolution of BI, products have been developed that analyze current and historical business information to assist with many recurring business management tasks and decisions. One challenge for such products is to be broad enough to meet the needs of many companies in many industries, which forces product design decisions that work well in the general case but may not be appropriate for any given company. To address a given company’s sometimes unique or specific ways of looking at certain business situations, the products must be customized, which creates maintenance risks and adds costs. That said, many of the products offered are excellent products that can reduce the time it takes to deploy a BI application. If the application is targeted for an aspect of company operations that is not critical for competitive advantage, such as accounts receivable analysis, it may well make sense to invest.

Analytical Platforms

We noted earlier that a BI environment might also include data sets to feed analytical algorithms used by operations researchers and management scientists to perform computationally intensive analyses of large data sets and thereby gain insight into complex business situations. Analytical platforms are toolkits of precoded software routines that execute linear programming, network optimization, forecasting, scheduling, simulation, stochastic programming, mixed-integer programming, and other applied mathematical techniques.

A developer of a BI application of this type would work with an operations research analyst or management scientist to define what data inputs are needed and in what form. The analytical platforms have user interfaces that allow for selection of appropriate analytical techniques, and these platforms prompt for the input values, which can be obtained from the underlying data store. These platforms range in price from limited function desktop versions costing less than $100 to multi-function versions costing from several thousand to hundreds of thousands of dollars. For example, many of supply chain management software vendors have analytical platforms offering dozens of standard software routines and a sophisticated user interface for developers to use. Some well-known analytical platform vendors include SAS Institute, ILOG, and SPSS.

Data Warehouse Appliances

Data warehouse appliances are a new category of IT product that is beginning to be found in some BI environments. The value propositions for these products are that they simplify the systems integration required for a enterprise class BI environment and they are optimized for specific BI and DW tasks, thus they provide greater performance at a lower cost. In effect, the appliance would sit between the transactional system and enterprise applications database shown at the left of Figure 6-4 and the BI applications on the right of the drawing. Our research indicates that the leading vendors in this new product space are backed by venture capital and that the products are being touted by some industry analysts and observers, not all of whom can be said to be objective. As with any emerging, “disruptive” technology, substantial gains may be gotten, but probably not without risks. We believe that these products warrant assessment and consideration for inclusion in high-performance BI environments.

6.2.3 Summary: Information Technology Assets Required for Business Intelligence

The IT products required for BI, if installed and configured properly, are mature, low-risk products, and there are proven technical methods for building BI assets such as data warehouses and data marts. One key general management task, then, is to ensure that your company chooses products effectively in relation to (1) a specific BI strategy and (2) the specific requirements of the BI applications that constitute your company’s BI portfolio.

Simply put—assuming that BI products are installed and configured properly—the risk is not in the product but in the selection process. Although it doesn’t cost the tens of millions of dollars that ERP and other enterprise applications can cost, an effective complement of BI products can run to several million dollars at the enterprise level. Therefore, an effective and informed selection process is important to the long-term health of the BI-driven profit improvement program. This highlights again the importance of knowing what your company wants to do with BI so that intelligent, cost-effective choices can be made. The other key is using these assets well to meet BI requirements, and that is the focus of the next section.

6.3 Business Intelligence Environment in the Information Technology Environment

For our purposes here, we will define the IT environment as including a development environment, a testing and integration environment, and a production environment. The BI environment encompass all of the development, information processing, and support activities required to deliver reliable and highly relevant business information and business analytical capabilities to the business. The BI environment exists within the broader IT environment.

Tip

A dedicated BI environment is likely to deliver better performance with fewer problems, but those benefits must be balanced against the fact that it costs more up front than a mixed-use environment. If it’s important to get top BI performance and your organization has ample funds, a dedicated environment might be the better choice.

From a business perspective, we must be concerned with how the IT assets required for BI are incorporated within the broader IT environment and how the business and IT policies governing that environment advance or detract from BI objectives. Because of business and technical differences between BI and transactional systems, an inherent tension exists within a mixed-use BI environment. Simply put, the policies that are appropriate for a large-scale transactional systems environment often impede aspects of BI development and operations. When a dedicated BI environment exists, the potential challenges are fewer, but in either case, the BI environment must be managed to achieve the following business and IT operational objectives:

Essentially, the general management task is to ensure that the BI asset that has been created is managed in a way that supports the company’s overall BI and business strategies. To accomplish this, we must recognize that BI capabilities should developed and managed in the same way that any other manufacturing or service delivery operations is managed: with a view toward supporting business strategy and delivering competitive advantage. Figure 6-5 and the associated thinking is adapted from manufacturing strategy ideas advanced by Robert Hayes, Steven Wheelwright, and others (Hayes et al., 1988) as Japanese companies were overtaking American companies in strategically important industries such as automobiles, steel, and electronics.

FIGURE 6-5 Progressive stages of business intelligence operational competitiveness.

Using the manufacturing example, a stage 1 company is capable of manufacturing the product or delivering the service in a way that does not detract from the overall operation of the company. The company’s marketing and sales plans, for example, are not held back by lack of product or ineffective service. Similarly, a stage 1 BI capability would enable an organization to deliver BI on an ad hoc basis, not detracting from the overall internal operations of the company.

At stage 2, using the manufacturing example, the company has moved beyond that first level of achievement to the point at which its manufacturing processes or service-delivery processes are the equal of its competitors in relevant ways, for example, in terms of cost, quality, service, cycle time, and/or asset utilization. This ensures that the stage 2 company is not losing ground in the marketplace owing to the performance of the manufacturing or service delivery function. Similarly, a stage 2 BI capability strives to match the ad hoc BI capabilities of its competitors, resulting in BI capabilities that are equal to, but not better than, competitors.

At stage 3, using the manufacturing example, the company has advanced again, this time to the point at which its manufacturing or service-delivery capabilities actually enhance the performance of key business processes or functions, as opposed to not holding them back. Similarly, a stage 3 BI capability provides information that enhances performance of key business processes and functions internally.

Finally, at stage 4, using the manufacturing example, the company has advanced to the point at which its manufacturing or service-delivery capabilities cannot easily be matched by its competitors, delivering a competitive advantage. Dell and Cisco are excellent examples of stage 4 companies. Both aligned people, processes, and technology so that they could outperform their competitors on cost, quality, and service. A stage 4 BI capability also cannot be matched by competitors. It provides the information needed within key business processes that results in a distinct competitive advantage in the marketplace.

Applying this thinking to BI operations, the general management and IT management task is to evolve and optimize BI operations to a stage that is appropriate for the company’s BI and business strategies. A number of major companies in a variety of industries have used BI to create competitive advantage, and thus they invested in people, processes, and technologies to become stage 4 companies, although they might not have thought of it in those exact terms. For other companies at a given point in time in their industries, it may be too late to achieve competitive advantage via BI, and thus becoming a stage 3 company may be the target.

Pitfall

Many companies fail to recognize that the technical environment and approaches needed to develop and support transaction systems are vastly different than those that are optimal for BI environments. Failing to adjust to the technical needs of a BI environment often results in technical failures.

Given the potential profit impact of BI, and given that more and more companies are seeing and exploiting the potential of BI, we believe that most companies should target becoming at least stage 2 companies, whereby their BI operational capabilities are equal to those of their strongest competitors. In effect, this means developing and optimizing two core BI technical environment processes: the development process, including testing and integration, and the production and support processes. We will discuss these in turn.

6.3.1 Business Intelligence Development Process

To support a BI-driven profit improvement program, the organization will need to invest in an effective BI and DW development environment. This environment should be used in conjunction with a suitable BI technical development methodology by IT people with suitable BI and DW technical skills. We talked earlier about the BI portfolio and the need to deploy BI applications as a series of releases, ideally every four to eight months once the appropriate BI infrastructure is in place. To accomplish this business objective, we need a suitable, repeatable, and cost-effective BI development process. Figure 6-6 shows the general development flow and the required tools.

Moving from left to right in the drawing, we see that the development process entails a flow between three environments, from the development environment through a testing and integration environment and into the production environment. The efficiency and effectiveness of those flows depends on having the appropriate tools, processes, and people. The specific processes may vary, but they will generally be akin to the processes described in Chapter 4 in the section about the implementation phase of the BI Pathway.

From a general management perspective, this all looks pretty simple, and it is indeed simpler in a dedicated BI Environment because the entire development process can be optimized for BI. Where it becomes more complicated is in a mixed-use BI environment, in which the development environment, the testing and integration environment, and the production environment are shared among BI, transactional systems, and enterprise applications. This sharing sometimes makes sense from a total IT operating cost perspective. However, its drawback for BI development is that the respective environments are generally optimized around the needs of the transactional systems.

FIGURE 6-6 Business intelligence development flow and tools.

Transactional systems are essential to day-to-day revenue generation, and the cost of having down-time could be catastrophic. Imagine the impact on Home Depot if its point-of-sale system were to be down or dramatically slowed. Because of these stakes, IT shops value-controlled change or minimal change once they get the transactional and large enterprise systems tuned and running at suitable response times. As a result, they tend to favor lengthy, thorough testing processes before new applicationsare allowed in the production environment. Meanwhile, as a cost-containment measure, companies tend to deploy heavily shared development and testing/integration environments, which can add months to the development cycle for BI and other applications.

The net effect of all this is that IT investment, development, and operating policies that make sense for transactional systems trump the needs of a BI environment. As a result, BI applications take longer and cost more to deploy than would be possible in an environment optimized for BI. We certainly agree that the requirement for stable transactional systems is paramount.

In a mixed-use environment, transactional systems tend to have priority over BI development because they contribute directly to the organization’s mission, whereas BI contributes only indirectly. That said, mixed-use environments can work well if you carefully manage the trade-offs between transactional systems and BI development.

That being said, it may be well for companies to evaluate the cost of a dedicated BI environment in relation to the opportunity cost of not fully realizing the incremental profits that could be captured if they had a more responsive BI development process that reduces “time to market” for new BI applications.

6.3.2 Business Intelligence Production and Support Processes

The BI production process is the means by which business information and business analytical capabilities are delivered for use in fact-based decision processes within core processes that impact profits. As such, the process must reliably produce high-quality business information, and the assets that support the process must be maintained and administered. The basic BI production process and key tasks are shown in Figure 6-7.

FIGURE 6-7 Business intelligence production process and key tasks.

Moving left to right, we see that data from the transactional systems databases and the enterprise applications databases flows into the data warehouse and then on to the BI applications, where it becomes available to users. As with the development environment, this all looks pretty simple, but the operational reality is more complex.

Whether operating in a dedicated BI environment or a mixed-use BI environment, the BI production process relies upon the production databases for the transactional systems and enterprise applications for data feeds, which means that the rules of engagement for BI are dictated by the needs of the transactional systems in the broader IT environment. The operational impact on BI is that, at a minimum, the regular batch data extract process must take place after the regular operating hours of the business so that the performance of transactional applications is not adversely impacted. Further, when operating in a mixed-use BI environment, other BI production processes, such as data transformation, data movement and loading into the data warehouse, data quality assurance, data movement, and loading into one or more BI applications, and resolution of any production problems must also take place after regular operating hours. In a global economy wired for electronic commerce via the Internet, the time available for such batch processes (the “batch window”) is shrinking, and other system tasks must also run during this same time period using the same resources. Further, the volumes of transactional data being extracted and moved into data warehouses on a daily basis is huge, further taxing shared IT resources.

Aside from the resource contention issues, large-scale BI production processes are nontrivial. BI production processes require large-scale system integration among various computing assets. When one of the many IT jobs within the BI production process fails, something may have gone awry at many places. Although we have great diagnostic tools these days and BI processes themselves are mature, moving huge amounts of data every night during a short batch window is subject to process errors. Accordingly, the manufacturing paradigm we introduced earlier is certainly a propos. By continuously improving BI production processes, we can help ensure that BI fully supports the business strategy and achieving a competitive advantage.

In addition to the BI production process, the need exists for a robust support process that includes maintenance and administration of the BI tools and support to BI users who have encountered BI application errors or who need to know how to use the BI application. Both of these types of processes are mature and supported by cost-effective tools.

6.3.3 Business Intelligence Human Resources

In addition to configuring a BI environment that supports a successful BI program, attention also needs to be paid to the BI human resources that are needed to ensure success. Similar to the specialized IT assets that are needed to configure a successful environment, technical success also requires dedicated technical specialists who have general expertise in techniques that are needed to successfully design and implement the BI environment. In addition, specialized expertise in the selected tools and technologies is needed to ensure that the tools are installed, configured, and used as intended. Too often, BI is considered “another IT application” that can be handled by IT staff trained to design and build transaction systems. The need for specialized expertise, trained to design and build these frequently large and highly complex environments, is not appreciated. In addition, the need to train technical staff in the specific tools and technologies that will be used to support the BI environment is not appreciated. It is common that IT staff is spread too thin, assigned to build and support both transaction systems and BI systems. This often results in a different type of technical risk.

Pitfall

Many companies fail to recognize the need for dedicated technical human resources that can focus on designing, building, and maintaining a large, and often highly complex, BI technical environment. Commonly, IT staff are asked to develop and support both transaction and BI environments. Inadequate technical human resources also adds a level of technical risk.

6.3.4 Summary: Business Intelligence Operations in the Information Technology Operational Environment

From a general management perspective, we must be concerned that the BI-driven profit improvement program is supported by an appropriate IT environment, IT operating policies, and specialized skills. This is harder than it seems because cultural differences exist within IT between the transactional systems and enterprise applications world and the BI world. Further, IT asset-optimization and cost-minimization policies, often driven by chief financial officers (CFOs), complicate the BI operation in ways that may not end up being supportive of the BI-driven profit improvement program.

Absent a strong CIO who “gets” BI and can drive for appropriate IT support for BI, the valid claims of both sides of the IT camp must be sorted out by general managers, many of whom are not IT savvy. What we’ve seen in these circumstances is that when the clamor for BI gets strong enough from senior leaders with profit center or cost-center responsibilities, the clout that the BI camp has increases and IT operating policies and asset decisions move toward greater enablement of world-class BI operations. Given the relatively low cost of a world-class BI environment and given the profit impact of BI, we believe companies would be well served to seriously evaluate establishing dedicated BI environments.

6.4 Summary: Business Intelligence in the Broader Information Technology Context

As we noted in Chapter 5, BI is but one management tool that can be used for profit improvement. Further, within IT, BI is one of many competing uses for scarce capital. Despite well-documented BI-driven profit improvement results by well-known companies in a variety of industries, we believe that BI continues to be underfunded within the IT portfolio. That is unfortunate because world-class BI capabilities with substantial profit impacts can be obtained for a fraction of what major companies have spent on ERP and other enterprise applications that have automated backroom activities but failed to impact the bottom line as promised. Looking ahead, the increased interest in BI that we see in the business community these days may be a harbinger of broader recognition of the profit potential of BI. With that recognition comes the general management task of ensuring that BI has its appropriate share of the management and IT resources required to turn BI into a competitive weapon.