Chapter 2

Figurative Animation

When animating you need look no further than the human figure for inspiration and challenge. If you can master the human figure in all its forms you can master anything.

BEFORE WE BEGIN

In the first chapter we covered some of the basic principles of animation which we will be dealing with during this chapter on figurative animation. At this point it might be useful to place these into context before going further by looking at the nature of animation. I have broken animation down into four categories of movement in an attempt to understand animated movement more fully.

THE FOUR ‘A’S OF ANIMATION

• Acting

• Animation

• Action

• Activity.

This hierarchical system describes the various levels of animation that can be achieved with the lowest at the bottom and the highest at the top. I have set out below an explanation of each of these categories, starting with the lowest, activity, and moving to the highest, acting.

Activity

This category simply describes the most basic form of movement we may witness and is the lowest form of animation. These movements are not associated with anything in nature at all and in this regard are completely abstract. An example of this would be of an image being at a particular point on the screen at any given moment and subsequently at another point on the screen the following moment. We can see examples of this in text rolling across a screen in a title sequence. Even though some of the objects that move in such a manner may display variable dynamics (they may move faster or slower at various points), they remain abstract and are not associated with any particular object that we recognize as being capable of independent movement.

Action

This category describes movement that can be attributed to specific objects such as we have covered in the previous chapter. The animation you made in the exercises there described the action of a bouncing ball or the action of a paper aeroplane. The fundamental difference between Action and simple Activity is that in an object’s action we understand that a type of movement may be associated with certain known objects, under certain known conditions and subject to the known laws of nature. For instance, we recognize the action of wind blowing through the leaves of a tree, the waves on the sea or the fall through the sky of a shooting star. These things do not intend to move this way, they simply do so as a result of the natural laws of nature and their own particular properties.

Animation

This describes the kind of dynamics that arise from within the subject matter. This can be seen in such things as a salmon leaping out of the water as it heads upstream to spawn, a humming bird collecting nectar from a flower or a dog scratching for fleas. All of these examples intend to undertake these actions. The key to this categorization is that the motivation for such actions comes from within the subject itself. While the humming bird, the fish and the dog are all still subject to the laws of physics and external forces, the manner in which they move is determined by their physiognomy and the particular motivations that instigate the action. Motivation for these separate dynamics may be as varied as the type of movements themselves; migration in order to breed, the search for food, or simple irritation. Whatever the motive for the movement, it has been an internal motivation; animation comes from within the subject – they intend to move that way.

Acting

This describes the highest level of animated movement. Not only are the movements subject to the laws of nature, with the route of the movement coming from within the subject (the subject intends to move), there are clear psychological reasons for these movements. It’s called performance! In this type of movement we experience the inner feelings of the subject of the animation. We can not only see what the characters are doing, but experience what they are thinking and feeling. This level of animation not only deals with variable dynamics, but the variations in mood and temperament necessary to build characters with personality. This is the most difficult task that faces any animator and is central to creating engaging narratives.

Before we begin to tackle figurative animation we need to understand the task that is ahead of us. Naturalistic figurative animation is perhaps the most challenging and demanding aspect of animation. The development of your animation skills should continue throughout your career as an animator, no matter how high you rise in the industry or how respected you become as an independent film-maker. It’s through naturalistic, figurative animation that these skills will be most severely tested. Why is this? Naturalistic animation of recognizable animals and humans is difficult to achieve because we all understand how people, dogs, cats, horses and the like are supposed to move, as we witness such movements first hand on a regular basis. As a result, our expectations are high and as such audiences are much more difficult to convince. Most of us can tell if a naturalistic figurative animation looks ‘right’ or not, you don’t need to be an animator to do that; however, it’s only through serious study that we can dissect the movement in detail and determine why things look right or wrong. It’s learning how to dissect such actions and discover the animation principles within them that is the purpose of this chapter.

As kids we may have developed the skills necessary to draw a funny cartoon horse or to draw figures in a particular cartoon style, perhaps slavishly copied from superhero comics. This is OK and I imagine that’s how many of us got started on the long road to art college, but it doesn’t help us much to develop the necessary skills to become a creative animator. At that stage it’s rather like seeing a dog balancing a ball on its nose – not a great trick, but you are amazed it can do it at all. If you are going to develop the skills of an animator you are going to have to learn more than simple tricks in order to get by. Figurative animation and the exercises set out in this chapter give ample opportunity to explore and practise all those basic principles covered in the earlier chapter.

Let’s start with the basic animation of a walk cycle, though we will see how even this most fundamental action can be a complex issue, before we progress onto various types of runs and then move on to cover in some detail the use of weight and balance in animation.

WALKS AND RUNS

In the previous chapter we looked at creating the first two levels in the four As of animation: activity and action. We are now going to tackle the next level – animation itself. We are going to make movements that involve the illusion of intent; the figures we make move should look as though they possess the motivation for the action and that purpose instigated the action.

Walks

The approach to creating a believable walk cycle is wrapped up in a wide range of issues related to physical and psychological conditions, and we will be looking into some of these later. There are simple step-by-step processes that you can undertake in order to achieve a fairly naturalist walk cycle and we will see that a fairly straightforward mechanical approach to a walk cycle will give you satisfactory results if all you require is to get a character from A to B. However, you should bear in mind that any naturalistic animation, no matter how simple, will demand a great deal of skill and observation on the part of the animator.

I was once on my way to discuss this very problem with the talented group of animators who created the Walking With Dinosaurs animation and the whole notion of characterization through a walk was going through my mind. As I made my way through the London underground system at rush hour, I observed the very thing I was going to discuss that day. Three people with very different types of walk just happened to appear as if on cue. A young woman walked quickly past me, obviously in a hurry to get to work. She walked confidently through the crowds, though she wore ill-fitting fashion shoes which had the double effect of throwing her body forward slightly and making her very flat-footed. Immediately on passing me, we were both delayed by the slow progress of a couple of commuters, one a rather large lady who rolled from side to side as her bulk shifted over the supporting leg. Her arms extending out at her side in an exaggerated manner only enhanced the effect. Her head pivoted slightly from side to side to counter the quite extreme to and fro action of her body. Her partner happened to be a rather tall and slender gentleman who had the appearance of being in ill health. He tried not to move too much, looking as though any extra vibration would disturb his already perturbed internal organs. He stooped slightly and held his head down to stare at the floor, as if uncertain of his footing. He almost shuffled along in a very stiff manner. Each of these actions had their own distinct qualities and were a result of different conditions, some external (the shoes), others physical (weight), still others psychological (uncertainty). The girl bobbed up and down, the large lady wobbled from side to side and the frail man moved stiffly with very little up or down movement at all.

It is easy to see evidence of all kinds of characterization through a walk. Consider for a moment the very famous and stylized walks of Groucho Marx, Charlie Chaplin, Mae West and Frankenstein’s monster. These are all instantly recognizable to the audience and clearly demonstrate the character within the figure.

Basic walk cycle

Simply standing up in a balanced manner demonstrates what a wonderful piece of engineering the human body is. Supported on relatively tiny feet, a tall figure is continuously balanced against the forces of gravity that would overbalance us and leave us in a heap on the ground. We constantly shift our weight on these two very small feet to stay upright; not only that, but we can do this on one leg (hopping), on the move (running and walking), on slippery surfaces (ice skating), in a strict rhythmical coordination with others (dancing) and while moving objects with the feet (playing football). These activities, based on our ability to balance, make the human body seem almost miraculous, but it’s the very act of unbalance that we exploit in order to do all of these. Walking has been described as controlled falling and when we analyse a simple walk we can see it’s exactly that. From a very early age we learn how to throw our weight forward (or backwards) in a controlled manner and purposefully become unbalanced. It’s this unbalance, driven by the forces of gravity, that provides the momentum for such elaborate movements. If we were to take no action at the moment of unbalance we would simply end up face down on the floor. However, we have learned the trick that if we swing a leg forward timed to coincide with the forward movement we can not only stop ourselves falling flat on our face, but we actually take a step forward. If we then use the energy from the controlled fall, we can go on to make a second controlled fall, and then a third and a fourth – it’s called walking.

Figure 2.1 Keep the design of your characters fairly simple and add no unnecessary details. Remember, the exercises are about animation, not design. If you base your drawings on a naturalistic figure and try to keep the proportions correct, you will find it easier to complete believable animation.

Figure 2.2 Your figures will be more easily read as animation if they possess some volume. Analysing stick-men type characters can become a little difficult once the lines are seen in motion, particularly in complex movements or actions where elements of the figure cross one another.

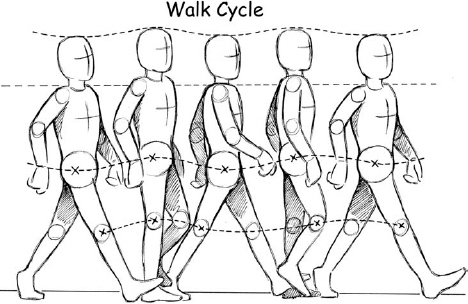

Figure 2.3 Notice how, in these drawings, we have the full set of movements that go to make up a full walk cycle. We can see how the body rises and dips at certain points throughout the action. As the leg swings forward and the figure is supported on one leg (the passing position), the body rises; as the leading leg makes contact with the ground (the stride), the body is lower. There are very few instances throughout a walk cycle where the body achieves complete balance. For the most part the figure is in a state of controlled ‘unbalance’. A mistake I have noticed many inexperienced animators make (particularly when animating models in 3D stop-fame animation) is to attempt to create a balanced figure for each of the drawings or model positions throughout the action. This results in some very strange actions, with the weight of the figure moving backwards and forwards in an exaggerated manner throughout the walk.

We can break the basic walk cycle down into two key positions: the stride and the passing position. From these, we can develop the other frames that are needed to complete the cycle.

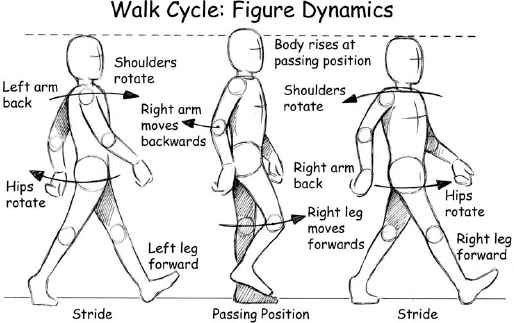

Figure 2.4 The stride is the position that demonstrates the leg outstretched as the leading foot makes contact with the ground and the trailing foot moves upwards onto the toes. The length of the stride will vary between walks and will be determined by various factors, as we shall cover in other examples. Notice how, when the left leg is forward, the left arm is placed backwards to achieve balance. This creates a counter-rotation of the hips and the shoulders.

Figure 2.5 The passing position is the frame whereby the leg moving forward in the cycle passes the leg that supports the body. When the figure is at the passing position the figure is balanced on one leg only. Notice how, when the left leg is thrown forward, the left arm moves backwards and the right arm is thrown forwards. When the figure is in the passing position the figure raises slightly as the supporting leg moves toward the fully upright position. These two positions alone, the stride and the passing position, form the basis for the walk cycle.

Figure 2.6 Once you have all the drawings completed for the cycle, it is easy to notice how the body rises and falls throughout the cycle. We can see how the head and the hips rise at the passing position as the supporting leg is straightened. The figure then moves downwards during the stride, due to the angle of the legs.

Figure 2.7 We can see in this illustration of the figure viewed head-on that the figure twists at the hips and the shoulders throughout the walk cycle and the counter-rotation of the hips and shoulders. The right shoulder is in a forward position when the right side of the hip is in a backward position.

Figure 2.8 The more drawings or frames you have within the walk cycle, the slower the walk will be. As the walk becomes slower, the length of stride will shorten. Conversely, if the length of the stride remains short and the speed of the walk becomes fast, you will get a very strange kind of fluttering or shuffling type of walk.

Once the stride and passing position have been created, it is a simple matter of flipping these two drawings or positions to create the next two needed for a complete cycle. Notice how, in the last illustration, the two stride drawings are fundamentally the same, though the one on the left has the left leg thrown forward while the right-hand drawing has the right leg thrown forward. You can make the second passing position drawing in the same manner.

The number of inbetweens needed to complete the cycle will be determined by the type and speed of walk you wish to achieve.

ANIMATION EXERCISE 2.1 – BASIC WALK CYCLE

Aims

The aim of this short exercise is to extend your understanding of animation timing and to develop an understanding of the basic principles as they apply to a walk cycle.

Objective

On completion of the exercise you should be able to create a short animated sequence of a basic walk that works within a repeatable animated cycle.

A few tips before starting the exercise:

Design

Design should not be an issue within these exercises and you should keep your drawings simple, with little or no detail. There should be no colour or shading unless absolutely essential and only in order to allow the animation to read more clearly.

Film language

Film-making is not an issue within these exercises. Remember, you are not telling a story but are attempting to complete a short animation.

Drawing

Work quickly though not hurriedly. Try to achieve consistent volume and weight within your characters. Do not concentrate your efforts on making beautiful drawings; rather you should be attempting to achieve beautiful animation. Do not overwork your drawings. Rather than rub out mistakes you should discard your drawings; this will help you keep up the creative flow.

Animation

Map out your animation timings on your key drawings, indicating clearly the number of inbetweens you initially expect to create. Try to time out the action by going through the motions yourself using either a stopwatch or a watch with a second hand. Do not forget the basic principles of animation.

Figure 2.9 To achieve a slightly more exaggerated and comic effect, you may choose to give the figure a little extra bounce. Notice how the figure is squashed between the point of contact and the passing position, a natural response as the knees act as a kind of shock absorber. In this example there is an additional squash added at the point between the passing position and the stride (contact); this position acts as a kind of anticipation to the stride and makes the whole action rather exaggerated. It is for this reason that I have chosen a rather more cartoon-like figure to demonstrate this unnatural and more cartoon-like walk.

Figure 2.10 Once again I have chosen a more exaggerated character to illustrate this point. The happy walk may result in a bouncier type of movement with a longer stride and a more upright aspect. The arms may also have a more pronounced swinging action to them. In this instance I have omitted the double bounce.

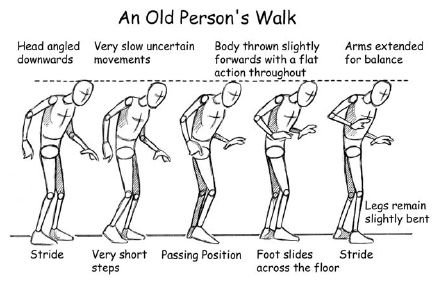

Figure 2.11 Such a walk will typically show the figure having a slumped posture. The much slower pace of this type of walk will affect the timing of all the separate elements. The stride will be much shorter and the timing far slower than within a standard walk cycle, though the dynamic progression (timing breakdown) may have a similar profile, with the slow ins and outs being in the same place. There may also be much less rotation of the shoulders, which will result in less exaggerative movement on the arms. Notice also how the foot barely leaves the ground through the passing position.

Figure 2.12 An old person’s walk may appear to be a lot more uncertain than a younger person, possibly as a result of unsteadiness on the feet. The overall timing will be noticeably slower and there will be very little bounce or up and down movement throughout. Consider how people that are uncertain on their feet use their arms during a walk; they may no longer be used as a secondary action swinging backwards and forwards, but may be outstretched slightly, perhaps to assist balance or to give additional confidence in anticipation of a fall.

Figure 2.13 A very young child’s walk may also demonstrate uncertainty, though this is more likely to be from lack of experience. When children walk at speed you may notice that they move with their arms outstretched as an aid to balance. There will be no evidence of the swinging-type action of arms countering the movement of the legs that you see in adults. The walk has a lot of bounce in it, perhaps most noticeable when children begin to run. Because the legs do not cushion the contact of the foot with the ground in the same way as adults do, there is a jolting of the head as a result.

Figure 2.14 You may notice in such a walk that the body is thrown back slightly, creating a centre of balance that is further back than is evident in a less heavy person. This is done in order to counterbalance the extra weight. You may also see this in heavily pregnant women; the additional weight at the front of the body results in the figure leaning back and curving the spine, which sometimes results in back strain. This may be accompanied by an increased sideways motion, swaying from side to side slightly to shift the weight more centrally over the supporting leg during the passing position.

Figure 2.15 This is a very similar walk to an overweight walk. There may be adjustments in posture to accommodate additional weight, with an increase in sideways movement to counter the additional weight during the passing position. The body is thrown backwards. You may notice that there is less bounce in such a walk and if the weight is extremely heavy you may see a kind of shuffle as a consequence.

Figure 2.16 An exaggerated sneak (usually reserved for more cartoon-like animation) will result in the body being thrown forwards and backwards, shifting the weight first over the trailing leg and then over the leading leg. This comes from the combination of the wide length of the stride and the slowness of the movement. In order to remain balanced throughout such a movement, the body weight must be constantly shifted over the supporting leg.

Figure 2.17 In a fast confident walk the body may be thrown forward slightly, the stride will widen and there may well be a greater swinging action on the arms. In this example the stance is very upright, though this is not necessary to achieve a confident look.

Figure 2.18 There are similar aspects of the sneak in this particular walk, with the body being shifted back and forth to remain balanced. Notice how the legs lift much higher off the floor as the foot is lifted out of the snow, moved forward and placed in the snow at a place further forward. It’s easier and more efficient to move the foot up and down out of deep snow rather than trying to push the foot through the snow and encountering resistance. You may notice a similar kind of walk when people begin to walk from the beach into the sea; at first, the shallowness of the water does not affect their walk, though as they get in deeper they will begin to lift their legs higher. Once they are in the water so deeply that this is no longer effective, they revert to a more normal walk, though leaning forward slightly as the water takes their weight.

Animate the character moving in profile either from left to right or right to left. Don’t concern yourself with the difficulties of perspective animation at this stage.

1. Make your first key drawing of the first stride position.

2. Make a similar drawing with the opposite arms and legs thrown forward.

3. Using the two stride keys, make the passing position drawing.

4. Make a similar drawing of the passing position with the opposite arms and legs thrown forward, just as you did with the stride.

5. Decide upon the animation timing and draw this on your key drawings, remembering to clearly indicate the slow ins and slow outs.

6. Make the inbetweens using the same process as described in the previous chapter.

7. Remember that the animation should work as a cycle.

8. Shoot your animation.

While this will give you the basis for the walk, it really does only cover the bare bones. Once you have mastered the basic principles you could attempt to create a more individualistic walk cycle through a series of animation exercises based on the examples here.

The number of different types of walk is almost endless and we have only just touched upon the topic; however, the basic principles remain the same. In order to get exactly the kind of walk you want you must try to imitate it, and through doing it yourself gain more understanding of the exact nature of the animation. If we choose to, we can observe such actions every time we go outdoors and as animators that is exactly what we should be doing. Using texts such as these, completing exercises and constant practice will help you to develop skills, but learning through observation will give you a much deeper understanding of the dynamics of the human figure.

Runs

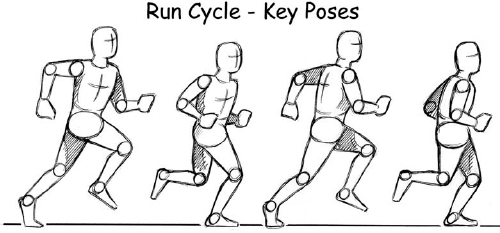

You will notice that many of the basic principles covered in a walk cycle also apply to the run. We can break down the action into a few simple positions to create the cycle, just as we did with the walk.

The variations on the run, as with the walk, are almost infinite and the examples illustrated here are very limited. With only a couple of exceptions we have covered the animation of a single adult character in a fairly realistic manner. Once you start dealing with figures of different ages and sizes and within different environments and under different conditions or cartoon animation, the options are limitless.

Figure 2.19 Just as in the walk cycle, the run can be said to be a condition of controlled unbalance. The one major difference between the run and the walk is the period within the run that the figure actually leaves the ground. This occurs slightly after what we termed as the stride within the walk. For an instance there is a period where neither of the feet support the figure; in effect it leaps through the air in a series of bounds. In the run cycle this is known as the suspended phase.

Figure 2.20 The stride in this case is the period whereby the figure is about to become unsupported and enters the suspended phase. The passing position remains fundamentally the same as in the walk. The passing position is the frame whereby the leg moving forward in the cycle passes the leg that supports the body. As in the walk cycle, it’s these two positions that form the basis of the cycle. Notice once again that as the left leg moves forwards the left arm moves backwards. Also notice how a running figure in the passing position, unlike the walk cycle, lowers slightly (squashes) as the supporting leg acts as a shock absorber. The figure then moves toward the fully upright position.

Figure 2.21 The timing of a run, rather like that of a walk, will be determined by the effect you are trying to achieve. The same general approach to animation timing is taken, with slow ins and outs appearing in the same place. While this may be varied to create other results, it is a good starting position to get a general understanding of the process.

Figure 2.22 In this front view we can see how the figure moves from side to side slightly as it is placed over the thrusting leg of the stride and the leading leg at the contact point.

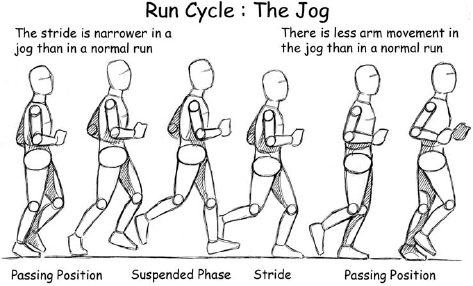

Figure 2.23 Jogging is generally less quick than the run. There is often just as much up and down movement as in a run but the strides are much shorter, though the backwards kick of the foot may be rather high. You will find there is much less rotation of the shoulders and the swinging action within the arms is much reduced and limited to short backwards and forwards action, usually keeping the hands in front of the body.

Figure 2.24 It is often the case that a fast run is animated with the figure leaning forward, but you only have to look at video footage of sprinters to notice the upright gait of the athletes. The stride is often very wide on a fast run and the arms may swing in an exaggerated fashion, moving well in front of the body on the forward action and trailing behind the backwards position. A figure may in fact lean forward a great deal when beginning the run, particularly if starting from blocks, and it may well lean heavily into the finishing tape, but for the most part it remains fairly upright.

Figure 2.25 A fast run cartoon style may incorporate not only an acutely angled figure, but the arms may also be extended out in front of the character. All manner of variations are possible to create a comic effect.

ANIMATION EXERCISE 2.2 – BASIC RUN CYCLE

Aims

The aim of this exercise is to extend your understanding of animation timing and to develop an understanding of the basic principles as they apply to a run cycle.

Objective

On completion of the exercise you should be able to create a short animated sequence of a basic run cycle.

Once again you should animate the character moving in profile from either left to right or right to left. Perspective animation can be rather complex and you should only attempt this after you have mastered the run cycle and gained confidence.

1. Make your first key drawing of the first stride position with the figure positioned as it is about to leave the ground.

2. Make a similar drawing with the opposite arms and legs thrown forward, as you did with the walk cycle.

3. Make the passing position drawings in the same manner as above.

4. Make similar drawings of the suspended phase with the opposite arms and legs thrown forward, just as you did with the stride and passing positions.

5. You now have the basic building blocks for your run cycle. Decide upon the animation timings and draw these on your key drawings. Ensure that the slow ins and outs are clearly indicated.

6. Create the inbetweens using the same process as described in the previous chapter.

7. Remember that the animation should work as a cycle.

8. Shoot your animation.

WEIGHT AND BALANCE

Weight and balance are two key factors in making believable animation. When dealing with an animated dinosaur of 50 tonnes or so, the animator’s job is to ensure that they display the kind of dynamics that make them look like they weigh that much. Conversely, animating a butterfly fluttering across a meadow needs equal attention to detail. To maintain the suspension of disbelief the animator must ensure that the former must not float and the latter should not plod. Coupled with weight, the animated characters must display that they are fully in control of their weight through continuous balance. The weight and, to a large degree, the timing of the animation will create the necessary balance within the animation of a character. However, we cannot approach these aspects of animation in isolation and we must constantly be applying all the other principles of animation covered in the previous chapter. It’s the very issues of weight, balance and timing that we recognize and relate to on a daily basis and make the animation believable – even if we see neither dinosaurs nor butterflies on a regular basis.

Weight

All animated figures, either naturalistic or cartoon-like, should possess weight in all their actions, which will vary depending upon the physiognomy of the character. How they use and deal with this weight may be dependent upon a number of other variables, such as age, their current mood, motivation and their overall psychological make-up. In addition to these factors, the figure may be subject to external forces such as gravity and affected by the load they are carrying; the actions of a deep sea diver or an astronaut on the surface of the moon will be very different from those of a figure on earth under normal conditions.

Balance

The balance of a character in motion may be linked directly to the intrinsic weight of the character. A very large figure may move in a certain manner as a result of their bulk. The age of the character should also affect the balance they display; a toddler will demonstrate a distinctive set of actions that are easily distinguished from those of a fit and healthy adult or the unsteady progress made by a frail old lady. Balance may also be dependent upon external factors such as the nature of the environment the figure is negotiating. A figure walking along a flat, even and solid surface will demonstrate a separate set of actions to one walking on an icy road or up a steep hill or along a tightrope. Carrying a load will also affect the nature of balance; a briefcase being carried by an adult may not result in any noticeable adjustment to the posture, though the same object carried by a young child may have extreme effects on balance. The size of an object as much as the weight may affect the balance of the figure carrying it. A large, fairly light object such as an empty wooden crate may necessitate more of an adjustment to the balance than a small heavy object such as a cannonball.

Figure 2.26 The location of the centre of gravity of an object relative to its supports will determine its stability. The closer the mass of an object is to the floor, the lower the energy state of the mass and the more stable the object becomes.

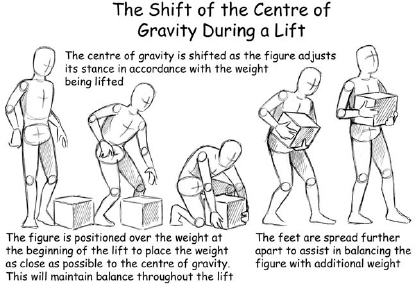

Figure 2.27 The attitude of the figure must take into account its centre of gravity. This will change once the figure takes on additional weight as it picks up a heavy object. For all intents and purposes we can assume that this additional weight now belongs to the figure. The amount of shift necessary will vary depending on the weight of the object and its distribution. An object held in front of the figure will result in the figure having to shift backwards to accommodate the centre of gravity.

Lifting

A lifting animation incorporates a complex series of movements that necessitates the shifting of the centre of gravity throughout the lift. The very act of a figure moving to lift an object will mean a shifting of balance; once the figure has taken on the additional weight it will have to realign itself in order to accommodate the weight. The position of the weight, its shape and even possibly the material it is made of may be determining factors in the way balance is maintained during the lift and once the object is supported.

Figure 2.28 By comparing the illustrations here we may assume that the first ball is a very light beach ball, in which case the balance is correct. We may also assume that the second ball is extremely heavy and the resulting shift in the figure relocates the centre of gravity. If the first ball is not a beach ball but is also heavy, then the posture is wrong. This is not a matter of the strength of the figure, it is a matter of balance. No matter how strong a person is, they must shift the body to place the mass centrally over the point of balance, otherwise they will simply fall over.

Figure 2.29 The physiognomy of a figure will determine the nature of the lift and the balance achieved. All figures, regardless of physical type or strength, will incorporate the lifted weight into a balanced attitude around the centre of gravity – or fall flat on their faces.

Throwing

Throwing actions also incorporate a series of movements that illustrate the shifting of the centre of gravity. The timing of the throw will be subject to the same principles covered earlier and the exact nature of the throw will be determined by the type of object being thrown, as well as the identity of the thrower. Very young children and some adults tend to throw in a very distinctive way, with a swift downwards action of the arm moving from over the shoulder downwards across the body and very little movement at the elbow. This is a very different action than we can expect to see from an experienced baseball player throwing a ball for example, or a skilled athlete throwing a javelin or putting a shot.

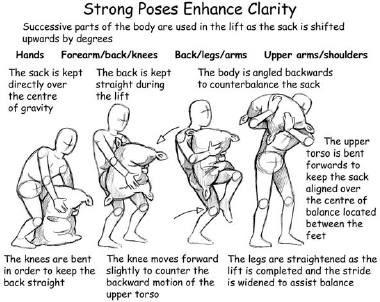

Figure 2.30 In this sequence there is an almost constant shift in the character as it lifts a heavy sack. At almost every point throughout the lift, balance is maintained in this manner. At the beginning of the action, even before the sack is lifted, the figure is aligned almost directly over the sack in anticipation of the need to place the additional weight at the centre of balance. We can also see in this illustration how strong poses for the key positions enhance the clarity of the action. Animation is much easier to read if you have strong, clear shapes in your key images.

Figure 2.31 The size, mass and shape of the object being lifted will affect the nature of the lift, its animation and its timing. All objects, no matter how heavy, will affect the balance of the lifting figure by varying degrees. In this sequence the figure is positioned over the weight in order to more closely align the centre of gravity. The feet are placed further apart once the object has been lifted to assist in the balancing of the figure. The wider apart the supports are, the more balanced and stable an object becomes.

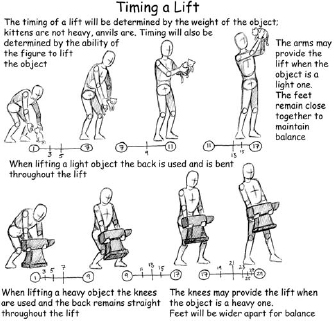

Figure 2.32 The timing of the lift will be determined by the weight and the nature of the object. The same principles apply to this action as were covered earlier in the section on the Newtonian laws of motion. Kittens are lighter than anvils and, as a consequence, have less inertia to overcome, so the lift will be faster.

Figure 2.33 The four keys demonstrate how the balance changes throughout the sequence during this throwing action. The arc of the throw is a major constituent of the action, with the hand coming from waist height, extending above the head and ending up across the body almost at knee level pointing at the ground.

Figure 2.34 In this example we can see that, at the beginning of the throw, most of the weight of the figure is supported by the trailing leg; as the throw progresses the weight is shifted forward and is supported by the leading leg. The action of this throw does not start with the arm or hand. It begins at the ankles. They pivot, moving the entire body forward; this movement progresses through the knees to the hips. The body is swung forward, followed by the shoulder, then the arm and finally the hand and fingers. This creates a whiplash type of action that flows through the entire body. As the throw develops, the figure needs to move the trailing leg forwards through the passing position and into a new forward position, as in a stride. During a more dynamic and energetic throw, the figure may gather so much momentum it is necessary to take one or more additional steps after the javelin has been released to regain balance.

Figure 2.35 In this animation, as with the javelin throw, the non-throwing hand is held out in front of the body at the start and swings backwards as the throwing arm moves forward.

Figure 2.36 During this throw, the bulk of the body plays a far more important role as it helps to lift the shot upwards. At the outset of the throw the figure has bent knees, so as the knees are straightened the shot’s inertia is overcome and momentum gained. The non-throwing arm is once again held outwards away from the body to assist in balance and pulled backwards during the throw to provide a counterbalance to the throwing arm and to assist with the upwards thrust of the shot.

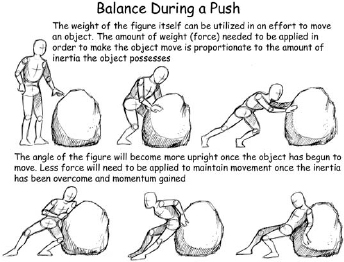

Pushing

During a push the weight of the figure may be utilized in order to induce movement in the object. Pushing a small object may simply require a limited amount of force, perhaps coming from the hand or the arm. With larger objects it will be necessary to increase the force in proportion to the object’s mass in order to overcome its inertia; this may necessitate the increased use of one’s own body weight. Newton’s third law of motion states that every action has an opposite and equal reaction. Effectively, if one pushes an object in a given direction there are opposing forces that ‘push’ in the opposite direction.

Figure 2.37 The weight of the figure may be utilized to apply the necessary force to achieve movement. The figure can lean into the push at an acute angle simply because the mass of the object is such that it ‘supports’ the figure. If this was a lighter object it would quickly move away from the figure, an unbalanced state would occur and the figure would fall over.

Pulling

As with the push there is clear evidence here of the third law of motion; the arms are pulling in one direction and the feet applying thrust in the opposite direction. Similarly, a figure engaged in a pulling action may achieve a position that appears unbalanced though is in effect supported by the mass of the object being pulled.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF ABOUT WEIGHT AND BALANCE

Q. Is the action naturalistic or stylized?

Q. Would the object behave like this in nature? Is it subject to the laws of nature?

Q. Does the overall animation display the sense of weight that is appropriate to the object?

Q. Does the object float?

Q. Does the object look balanced throughout the action?

Q. Is the centre of gravity in the right place?

Q. Does the centre of gravity shift throughout the action to accommodate the weight of the figure and to maintain balance?

Q. How does the physiognomy of the character affect its balance?

Q. What other factors impact upon the balance of the object or character?

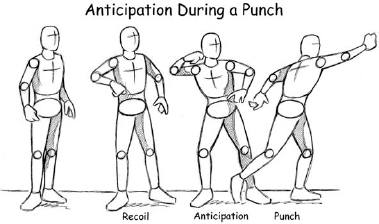

ANTICIPATION

Almost all actions are preceded by an anticipation of that action. We can see this anticipation in the throw, the push and the lift that we have just covered. In some instances it is a physical requirement of the action. In order to jump upwards it is necessary first of all to move downwards by bending the knees. Anticipation also helps the animator to communicate clearly to the audience what is going to happen next. Often, there is no physical need to undertake an anticipation of an action; we do it simply as a result of thinking about something before we do it. We may lift our hands upwards slightly before we reach downwards to lift an object off the floor, though there may clearly be no physical reason for this. Adding anticipation to an action strengthens the action and adds clarity to the movement; however, if it is overdone it may result in a very staged and exaggerated, cartoon-type action that is reminiscent of the silent movies. Before the advent of sound, actors would often exaggerate their actions to make them more easily read. Chaplin was a master of this. Though far from being a simple pantomime figure, he mastered the technique and was able to use just the right amount of exaggeration to enhance the action, adding clarity and keeping the action subtle. This gave him the scope to cover a huge range of emotions without recourse to dialogue, and for this reason alone he is worthy of very serious study. Anticipation prepares your audience for what is coming next and if done well it won’t give the game away.

Figure 2.38 Notice how the figure leans over in an increasingly acute angle as the strain is taken up. The centre of gravity shifts to such a position that if the object was no longer there the figure would fall over. The mass of the object acts as a counterbalance to the weight of the figure until such a point that the backwards thrust applied to the ground increases to a high enough level to overcome the inertia of the object and the object begins to move.

Figure 2.39 In these examples you can see how the arm has to move backwards first in order to provide the forward thrust of a throw.

Takes

A take is a kind of anticipated action that is generated not by premeditated preparation for a movement but more by surprise experienced by those doing the take. This can be quite subtle or it can be extremely exaggerated for comic effect.

Figure 2.40 As in the throw, the punch can only be delivered if an anticipated action precedes it. The arm moves backwards before moving forward for the blow.

Figure 2.41 In this case the entire figure anticipates the move. In order to jump forward from a standing position, the figure squats down in readiness for the spring upwards. In this way, energy is stored within the legs during the anticipation and then released during the jump.

An argument in support of life drawing

To understand we must see and experience. Sight is a facility most of us possess; to see is a purposeful act of investigation. One way we can develop the skill of perception is through life drawing. The act of drawing will not only improve your mark-making skills and develop a facility with a range of media, it also forces you to observe your subject very carefully. I had a group of students studying computer animation who demonstrated a deep reluctance to attend any of the life drawing classes provided for them, while their colleagues working in 2D or 3D animation would show up regularly. Their concern was that they couldn’t draw too well and they didn’t see the relevance of life drawing to their studies and their practical work. Their stance was: why should they learn to draw, they were working in computer animation after all, and that stuff was for the traditionalists not techno whiz-kids. I met up with a few of these students at a studio where they were working shortly after they graduated and they were somewhat coy about letting me know that they had arranged life drawing classes of their own. It turned out that the old boy with the pencil was right after all. Do not become despondent if you are not confident in your drawing skills; this does not mean you will not be a good animator. There are many first-rate computer animators and stop-frame animators who are not comfortable with drawing, but what they do have is a profound understanding of how things move, behave and perform. Performance is the thing. Life drawing, in this instance, is only a means to an end, the end being observation and understanding. If you can get this same level of understanding through any other method, studying films, observing people and animals in motion, making videos or taking photographs, then that is the way forward for you. There is no one way.

Figure 2.42 In this example we can see the starting position is the figure at rest. It then moves down in anticipation of the take (squash). This is followed by the extreme position of the take (stretch), instigated by an event that causes any number of reactions: surprise, fright or joy. The completion of the take is when the animation settles into its final position. This need not be limited to the face and the head, it can affect the entire figure. Laurel and Hardy were masters of the take and double take, which often involved total body movements including grabbing their hats, ties or even one another.

Figure 2.43 The double take works along the same principle as the take, though there is a second anticipation position before the reaction position. This is often used in more cartoon-like animation for comic effect.

It is my business to know things. Perhaps I have trained myself to see what others overlook.

(Sherlock Holmes, in A Case of Identity by A. Conan Doyle)

One final thing: it may sound obvious, but it is important to have a clear idea about what you are trying to achieve in an action long before commencing animation. Your ultimate intention should be to make your characters look like they intended to make the movement and that the motivation for the action comes from within them. The hand of the expert animator becomes invisible; they no longer animate, they allow their characters to give a performance and the characters become so believable that they begin to exist as real entities. If you don’t believe me – just ask Bugs Bunny!