3 Understanding Financial Statements

To an untrained eye, looking at a typical financial statement can be a frustrating experience. What do all those numbers and terms mean? Can worthwhile information about the financial health and future of a media business be gleaned from this puzzling array of numbers and unfamiliar words? The answer, of course, is yes, given a little tutoring. William “Rick” Mangum and Glenn Larkin take away some of the mystery surrounding financial statements, and demonstrate how they can serve as valuable tools for making many management decisions. Rick Mangum is Vice President Broadcast Accounting for Clear Channel, one of the country’s largest media companies. Glenn Larkin wrote the original version of this chapter while VP and Controller for Bonneville International Corporation.

Introduction

By analyzing financial statements, managers can make decisions based on fact rather than intuition or imperfect knowledge. Essentially, these statements constitute management’s road map for monitoring the operating performance and financial health of a business. They also help managers to make intelligent decisions about cutting costs, discovering revenue-growth opportunities, improving productivity, and evaluating competition. A management team without the expertise to prepare financial statements or the ability to interpret financial statements is like a baseball team insisting that a shortstop play without a glove.

The accounting profession has developed standards of preparation of financial statements called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). These standards are driven by a number of conceptual guidelines that provide reporting consistency from company to company, industry to industry, and time period to time period. This chapter introduces these guidelines for financial statement preparation, and discusses the many uses to which the statements can be applied.

Financial Statement Uses

Each financial statement can serve the needs of many different users. A user may be defined as any entity, lender, regulatory agency, person, institution, or government entity that has a “need to know” and/or a “right to know” about the financial activities of a business. Financial statement users in a broadcast or cable setting may include station or company management (including department heads or project leaders), lending institutions, taxing authorities, investors, regulatory agencies, and certain employees. Each of these users requires specific information. For example, banks often need financial statements showing detailed liability information. Investors—interested in such metrics as earnings per share, dividend potential, and taxing authorities—require financial statements to substantiate income and deductions constituting the basis upon which taxes are assessed.

Internal use by management will likely represent the most common use of an entity’s financial statements. Management relies on these reports to make daily operating decisions regarding the current and future course of the television or radio station or cable system. Very simply put, timely information given to management should result in accurate decisions leading to increased productivity and profitability. Such a variety of needs suggests that an accounting and financial system must be geared to fulfill all of the reporting requirements of a business. Further, preparing statements suitable for many users requires skills beyond simple accounting.

Financial Statement Preparation Conventions

To understand a financial statement, the reader must understand some of the conventions used in its preparation. Financial statements basically function as a measurement medium. Whether it is the measurement of a bottom-line result, of cash flow, or of total debt at year-end, each requires the use of certain GAAP guidelines. When these requirements are met properly, auditors examining the quality of these statements will issue what is called a clean opinion certified statement. The following constitutes a brief discussion of the more important GAAP conventions.

Cost Basis

The “cost” principle is used to value and record the expenses, inventories, broadcast rights, and other assets of a business at amounts that represent their purchase cost or some other acceptable cost measurement. This cost valuation brings “structure” to the measuring and reporting of activities, such as the portion of expended services or assets utilized in operating the business during a measurement period, or the portion that remains at the end of a time period. If an asset’s cost exceeds its market value (the realizable value), the asset has lost value in that time period, and a charge for the amount of the decreased value must be recorded in the financial statements. In a broadcast or cable business, the “cost” convention applies to all asset and expense categories. It applies to the valuation of tangible assets, such as a transmitter or cable facility, as well as to an entity’s intangible assets, such as talent contracts, FCC licenses, and cable franchise agreements.

Realizable Value

Another accounting guideline used in the preparation of financial statements is the “realizable value” convention. It is used in the measurement of revenues, sales, or gains of a business. The recording of revenues in the financial statements is measured by the value of the cash “realized” in return for the goods or services sold. For revenue to be recognized, several criteria must be met: (a) services must be rendered or goods received by the buyer, (b) there must be evidence of an arrangement with a fixed or determinable price, and (c) collection must be reasonably assured. In a broadcast or cable setting, this convention applies to commercial spots aired and cable programming provided to subscribers, as well as to all other types of customer sales.

When teamed together in the preparation of a financial statement, the “cost” and the “realizable value” conventions provide for meaningful measurement of net income or loss. Without these two rules, financial statements would include inconsistencies and unguided value judgments on the part of statement preparers and users.

An example of a misguided judgment would be the temptation to record revenues for signed but unperformed contracts, resulting in an improved bottom line that would encourage plans to float a public stock offering. Similarly, costs incurred in a transaction could be recorded at an amount less than the purchase price, temporarily increasing the bottom-line result. In this case, the reason may be a belief that future revenue potential justifies recording the lesser charge initially, and then carrying a higher portion of the costs into later time periods. The “cost” convention and the “realizable value” convention steer both preparers and readers of financial statements away from misrepresenting the true financial bottom line of a business.

Matching Principle

In the preparation of financial statements, the “matching” principle is used to define and measure those costs and expenses incurred in producing the revenues and resulting assets of an operation. This “matching” concept is particularly important in the preparation of the income statement. It requires that expenses, such as sales commissions, though perhaps not paid, be deducted from the revenues in the period the “revenues” are generated, in order to provide a meaningful measure of the true return at the bottom line. Hence, at the end of a measurement period, many unpaid expenses need to be accrued.

Where inventories are involved, this matching principle becomes even more critical because inventories associated with revenues realized in a financial statement must also be clearly reflected as a cost deduction in calculating net income. A simple example of this might be 2,000 DVDs sold at $25 each for a total of $50,000. Having been produced and held in inventory at a cost of $15 each for a total of $30,000, the gross profit on these video sales shown on the income statement should be the net of the two, or $20,000.

Similarly, though taxes are reported and paid according to a predefined timetable outlined by the tax authority, within the financial statements, taxes must be accrued and “matched” against the revenue or income to which they relate.

Conservatism

The GAAP “conservatism” principle requires that when it is difficult to evaluate the benefit of an expense or when an expense has questionable continuing value, that expense must be reported as a deduction early in the accounting process. This is to avoid carrying such costs on the financial statements as if the expenses were still contributing value to the business. Certain expenses may need to be accrued at the end of an accounting period to bring conservatism to the bottom line. Similarly, revenues and gains cannot be recorded until a bona fide revenue transaction is complete and any necessary contracts are signed to document that there will be “realizable value” received by the business. The conservatism convention avoids overstating profit and the value of assets, or understating losses and liabilities—all of which can negatively impact the reported financial status of an operation. For example, conservatism within a broadcast or cable setting suggests that purchased programming that is intended to be aired over several time periods, but whose value to any one period is not specifically known, should be taken as an expense in the financial statements on an accelerated timetable (i.e., in the earlier accounting periods) to avoid overstating the value of the program.

Conservatism would also dictate the speedy write down of an unpopular program acquisition that has deteriorated value to the business—meaning poor ratings, and therefore disappointingly low commercial rates. An example of deterioration might be a syndicated talk show that has provided a reasonable return for a TV station (i.e., good ratings). After a better-rated program is scheduled against the talk show by a competitor, the first show’s value experiences a decline because the station will no longer command the same spot rates and resulting sales. Unfortunately, the station may be forced to absorb a cost or charge to its income statement.

Materiality

The convention of “materiality” requires that determinations be made as to the level of detail and the dollar level of activity (or balances) that should be reported to facilitate meaningful decision making. What constitutes a “material” amount for one business may not be sufficient for another business. Materiality in financial reporting is defined by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 in the following manner: “Items are considered material, regardless of size, if they involve an omission or misstatement of accounting information that, in light of surrounding circumstances, makes it probable that the judgment of a reasonable person relying on the information would be changed or influenced by the omission or misstatement.” In other words, a material item is one that if reported improperly, could cause people to make a false judgment or the wrong decision.

Although there are other accounting “conventions,” those discussed here represent the basic framework within which financial statements are prepared. These guidelines provide for comparability, consistency, and understanding of the financial statements, whether used internally by management or externally by other users. Without these governing “conventions,” numbers would be dropped into the statements more or less at random, thus rendering the financial statements less useful.

Accounting Periods

As the accounting conventions discussed above are applied to the business activities of an entity, a decision is required regarding the time period to be measured. Like any report, financial statements require the designation of an appropriate time period for the measurement of profits, losses, and reporting date for assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity. (These terms will be defined in detail later in this chapter.) In general, the income statement and the statement of cash flow measure activity over a time period, such as individual months, individual quarters, or a combined year. On the other hand, a statement of financial position reports balances of assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific date. Financial statements can be prepared and published as frequently as management or other users desire; however, the administrative costs, labor, and time associated with preparation need to be considered.

Many broadcast and cable operations, like other businesses, use quarters and calendar years as their reporting time frame. A fiscal year may be designated in lieu of the calendar-year approach. Sometimes more than one reporting time frame will be used for different financial statement users. Once selected for reporting, an annual period may be broken down into monthly or quarterly interim-reporting time segments, depending on the need for more-timely financial data. Such interim-period financial statements are used by management, and may be less precise or less detailed depending upon their planned use. Most state and federal tax authorities, as well as regulatory agencies, require annual financial statements.

Management’s report to stockholders is likely to be prepared on an annual basis, and is generally audited before being published. Audited financial statements require a higher level of scrutiny in their underlying accounting procedures.

Once the accounting periods and cutoff dates have been established for financial statement preparation, the same time frames should be consistently used over subsequent reports when possible. The continued use of similar reporting periods facilitates comparability in the underlying data from period to period. This comparability allows better evaluation of the progress of the business. Certainly, if there is a justification for changing accounting periods and report dates, that situation can be accommodated, but the advantages of year-to-year comparability will be lost during the transition.

Financial statements must contain a clear heading that states the time period they cover, using language such as “For the 12 months ended December 31, 2xxx,” or “As of December 31, 2xxx.” If prior-period financials are included for comparative purposes (and they usually are), the heading will reflect the periods and dates presented.

Financial Statement Descriptions

Four principal financial statements typically are prepared and published together. They include:

1. The Statement of Operations (sometimes referred to as the Income Statement or the Statement of Profit and Loss, abbreviated to P&L)

2. The Statement of Financial Position (sometimes referred to as the Balance Sheet)

3. The Statement of Cash Flows

4. The Statement of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity (or Owners’ Equity)

Although each statement has a separate and distinct function, they are interrelated, and, as business activity occurs, the data move among them. The following section discusses the basic purpose of each statement in a broadcast context, together with an illustration of each.

The Statement of Operations

This financial statement measures the operating results of the cable system or broadcast station/market, and thereby reflects that entity’s profitability. The term “bottom line” literally comes from the last line of this statement, which usually indicates net income or net loss. The P&L (Profit and Loss) Statement is the common term used for internal financial reporting. Operating managers typically are evaluated and compensated based on the financial performance of the station as indicated on the P&L (see Figure 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1 Broadcast P&L used for internal purposes.

Revenue includes all the sales and other taxable income of the business, excluding gains on the sale of property and any extraordinary items (see Chapter 4).

Operating expenses are all the costs of doing business, including salaries, employee benefits, supplies, and services required to operate the station efficiently—and, management hopes, profitably (see Chapter 5).

Depreciation and amortization constitute a special category of operating expenses, representing a noncash charge to the period being measured of costs associated with long-term assets. Depreciation represents the allocation of the cost of the station’s or system’s fixed assets—such as its studios and equipment—over the useful life of those assets. In a similar way, amortization constitutes the “depreciation”—or write-down costs of doing business—associated with intangible assets (nonmonetary assets that cannot be seen, touched, or measured), exhibiting a limited life span of usefulness. Certain indefinitely lived intangibles (e.g., trademarks and FCC licenses) are not amortized. These assets are subject to possible impairment charges (determined by subtracting the asset’s fair value from its book value) if the discounted cash flows are not adequate to recover the cost of indefinitely lived intangibles.

A P&L statement may be more useful when other data are included against which current operations can be compared. For instance, actual results are commonly compared to proposed budget expectations, and also to prior performance of the same month one year ago, referred to as year-to-date information. The monthly information gives management a sense of what happened in the most recent operating period, whereas the year-to-date figures represent cumulative results since the last fiscal-year reporting date.

Other operating analyses might include the calculation of earnings per share, profit margin, or percentage variances of revenue and expenses as compared with budget or prior periods. Expenses are commonly broken down into fixed and variable portions to determine controls that can be exercised realistically over discretionary spending. As the name implies, variable expenses are those costs that tend to vary in relation to increases or decreases in revenues, such as sales commissions. A sales executive who exceeds his or her expected sales budget increases station revenue—but at the same time, he or she increases commission rewards (a station cost) for achieving such a high sales figure. Again, as the name implies, fixed expenses generally remain constant despite variations in revenues. Examples of fixed expenses include transmitter maintenance and leasing agreements.

In the sample station P&L exhibit (Figure 3.1), most of the variable costs are found in the sales categories, such as commissions earned by sales personnel and national sales-representative firms. Most other broadcast and cable programming costs are relatively fixed across different levels of revenue over time.

A cable operator’s costs, in contrast to broadcast, will increase as subscribers are added. This includes hardware, contracted installers’ fees, subscriber-based program fees to networks (based on the number of system subscribers), and franchise fees to the communities served. Some costs do not increase proportionately with subscriber growth—such as a base level of trunk, headend, and feeder-system costs that are incurred initially and represent fixed expenditures. Both fixed and variable expenses have a significant impact on the well-being of a business. For best results, these expenses should be monitored and managed separately.

Certain items such as income taxes and interest payments are typically included separately at the end of the income statement. This manner of presentation is informative for several reasons. First, it facilitates the calculation of a profit before interest and taxes, which provides a pure measure of the efficiency of a reporting unit. This is because interest and taxes typically cannot be controlled by the management of a media operation, and therefore should not interfere with performance evaluations. Profit after interest and taxes, however, represents the true “bottom line,” which is a critical measure for investors, lenders, and operating personnel.

Statement of Financial Position

This financial statement reports the balances of the assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity of the broadcast or cable entity. Hence, it is sometimes referred to as the “balance sheet.” A simple formula is used in formatting the balance sheet, Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity, suggesting that the assets owned by the operation are either financed by debt (liabilities) or owned by the partners or stockholders. The value of the assets must, therefore, sum to the total of the liabilities and owners’ equity. The statement of financial position (see Figure 3.2) describes the types of assets owned and their nondepreciated cost, as well as other key data such as the amount of debt imposed on the operation.

Figure 3.2 Statement of Financial Position.

The categories of current assets and current liabilities are those that are expected to be realized or paid within the following 12-month period. Current assets represent those assets expected to be collected or consumed by the operation of the business within the 12-month period, such as cash or accounts receivable. Current liabilities represent the amount of payables or debt due during the same 12-month period, such as accrued bonuses and accounts payable. A financial statement reader can get a quick view of the near-term financial stability of the operation by comparing current assets with current liabilities on the balance sheet release date.

Other assets and liabilities of the operation are generally reported as “long term,” suggesting that their contribution to the operation will exceed 12 months. The individual classifications of assets and liabilities reported on the balance sheet are likely supported by numerous accounts in the general ledger, combining to the totals shown on the report. The general ledger is a summary of every transaction that occurs, and serves as the building blocks, or raw material, for all of the other financial statements described in this chapter. Typically, any material items or balances, whether assets or liabilities, short or long term, are broken out and identified separately on the balance sheet to add transparency regarding business activity.

As the media entity conducts business—such as selling airtime, incurring expenses, or buying capital equipment—the balances of the assets and liabilities consequently increase or decrease on the balance sheet. The net change of all such activity is reflected in the equity section. The net change in equity (exclusive of dividends or other capital transactions) from one period to the next is also the net income shown on the income statement. Assuming the enterprise is profitable, equity can be distributed to owners and shareholders in the form of dividends.

Reading the balance sheet usually starts with current assets followed by various asset classifications, and concluding with liabilities. In reviewing liabilities, readers commonly compare the duration and size of the liabilities to the assets available to pay down, or liquidate, the debt. The net result minus liabilities from assets is the equity, or book value, of the business. When reviewing the balance sheet, the reader seeks to identify whether there has been overall improvement or deterioration in the owners’ interests. Of course, the various users of financial statements will place varying degrees of emphasis on different sections of the balance sheet. A lender, for example, might give significant attention to the liquidity (i.e., easily converted to cash) of certain assets that will be called upon to pay down a loan. A system or station manager, on the other hand, may be interested in the cash position or the assets against which he or she might borrow money. A prospective buyer of the operation might be interested in the future cash flow generating potential and the value of the long-term assets such as an FCC broadcast license or a prime real estate location.

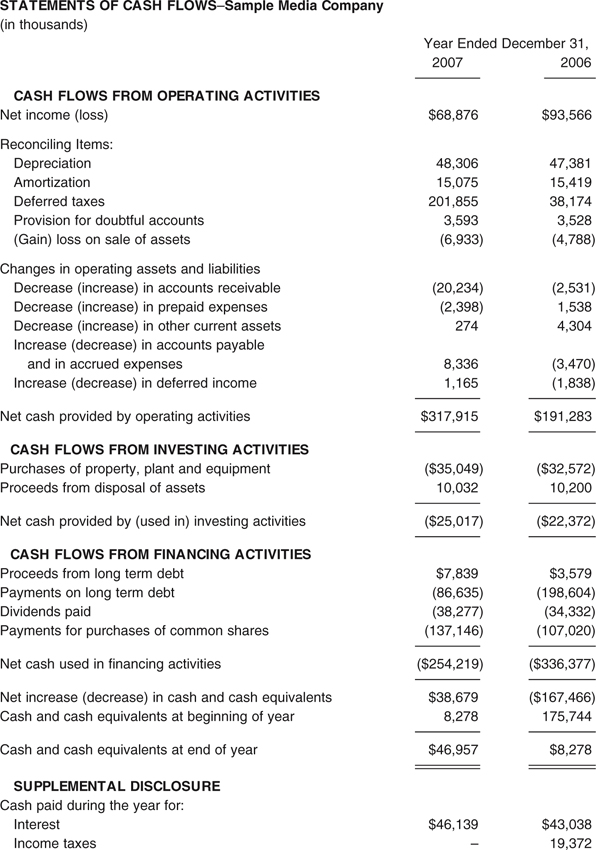

Statement of Cash Flows

The statement of cash flows, as one might guess, reports the sources and uses of dollars coming into and going out of the business during the period specified. It also reports on the beginning and ending dollar balances for the period. This statement reveals how changes in balance sheet and income accounts affect cash. The analysis is typically broken down into three categories: (a) cash flows from operating activities, (b) cash flows from/to investing activities, and (c) cash flows from/to financing activities (see Figure 3.3). From a management perspective, this statement indicates the operation’s ability to meet its short-term debts. As such, it is particularly useful to bankers, investors, and local management.

What is included under “operating activities,” “investing activities,” and “financing activities” may vary among types of business, but the distinctions are more a matter of the degree of emphasis placed on the transactions that drive revenues and profits. Cash flow from operating activities summarizes revenues and expenses from day-to-day operations (e.g., sales, salaries, rents). Investing activities constitute the major areas of operations and asset categories in which cash is committed to ultimately generate a return to owners. Financing activities are those used to fund/finance business operations; they include debt and equity.

When evaluating a cash flow statement, it is important to look at the sources of the company’s cash. Are operating activities generating enough cash to provide continued growth (investment opportunity) or dividend payments? If the cash flow is generally originating from financing, what are the company’s debt ratios (debt capital divided by total assets)? Is there buildup in accounts receivable and inventories, reflecting a slowdown in cash flows with which to liquidate payables and debt commitments?

FIGURE 3.3 Statements of Cash Flows.

The cash flow statement functions as a bridge between the P&L and the statement of financial position. All three financial statements have a critical role to play in the analysis and monitoring of business activity. A financial statement user should have a complete set of all three statements before commencing a review.

Statement of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity

The Statement of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity itemizes the changes in equity over the period covered—including investments by owners and other capital contributions, earnings for the period, and distributions to owners of earnings (dividends) or other capital. This statement is required only when there has been a change that cannot be readily determined from other sources—that is, something other than earnings that affects the value of shareholder equity. Figure 3.4 provides examples of some such changes.

FIGURE 3.4 Statement of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity.

Financial Statement Footnotes

The grouping, summing, and subtracting of numbers in financial statements in and of itself sometimes is inadequate to present a complete picture of business activities. Consequently, parenthetical notations are often found within the statements themselves. Another option is to include some text—referred to as footnotes, or just notes—in addition to the financial statements. The notes must be read in conjunction with the basic financial statements, and should provide additional explanation of the many accounts of an enterprise. The financial statements will reference relevant footnotes at key points within the data disclosures. Examples of items typically found in footnotes include significant accounting policies; a breakdown of asset types included in the long-term-asset category; information on acquisitions and divestitures; investments; tax disclosure; long-term debt, commitments, and contingencies; and share-based compensation.

Footnotes typically clarify in more detail information revealed in the standard financial statements, such as descriptions of revenue recognition conventions or detail on debt instruments. Footnotes may also explain unique aspects of the financial statements. In fact, to a sophisticated interpreter of financial statements, the footnotes may be the most informative portion of the financial statements.

It should be noted that the majority of the statements discussed in this chapter are examples of those used internally. Publicly reported statements prepared to conform to public accounting requirements may be presented in a different format. The purpose of internal statements is to help management evaluate performance. Publicly reported statements are intended to help shareholders both evaluate their investments and compare investments across industries.

In Conclusion

No operator of a broadcast station or cable system can effectively manage operations without the aid of standardized financial statements prepared on a monthly, quarterly, or annual basis. Recognizing that many broadcast and cable professionals are not accounting experts, having qualified accounting personnel review these statements with these operational managers is a good idea. Once management understands the financial patterns and trends uncovered in these reports, financial statements will become important tools in recognizing problems, seizing opportunities, and, ultimately, earning a reasonable return on investment for owners and shareholders.

Notes

1. We would like to acknowledge the work done by Glenn Larkin for the 1994 version of this book, whole portions of which were again used here.