1

GENERAL DISCUSSION OF ACCOUNTING/STATISTICAL STANDARDS: BENCHMARKING

MEANING OF ACCOUNTING/STATISTICAL CONTROL

Control by definition assumes that a plan of action or a standard has been established against which performance can be measured. To achieve the objectives that have been set forth for the business enterprise, controls must be developed so that decisions can be made in conformance with the plan.

In small plants or organizations, the manager or owner personally can observe and control all operations. The owner or manager normally knows all the factory workers and by daily observation of the work flow can determine the efficiency of operations. It is easy to observe the production effort of each employee as well as the level of raw materials and work-in-process inventory. In most cases, by the observation of the factory operation, inefficiencies or improper methods can be detected and corrected on the spot. The sales orders can be reviewed and determinations made about whether shipments are being made promptly. Through intimate knowledge of the total business and communicating on a daily basis with most employees and customers, the owner is able to discern the effectiveness of sales effort and customer satisfaction with the products.

However, as the organization grows, this close contact or direct supervision by the owner or manager is necessarily diminished. Other means of control are required to manage effectively, such as accounting controls and statistical reports. By the use of reports, management is enabled to plan, supervise, direct, evaluate, and coordinate the activities of the various functions, departments, and operating units. Accounting controls and reports of operations are part of a well-integrated plan to maintain efficiency and determine unfavorable variances or trends. The use of the accounting structure allows for the control of costs and expenses and comparison of such expenditures to some predetermined plan of action. Through the measurement of performance by means of accounting and statistical records and reports, management can provide appropriate guidance and direct the business activities. The effective application of accounting controls must be fully integrated into the company plans and provide a degree of before-the-fact control. The accounting/statistical control system must include records that establish accountability and responsibility to really be effective.

EXTENT OF ACCOUNTING/STATISTICAL CONTROL

Effective control extends to every operation of the business, including every unit, every function, every department, every territory or area, and every individual. Accounting control encompasses all aspects of financial transactions such as cash disbursements, cash receipts, funds flow, judicious investment of cash, and protection of the funds from unauthorized use. It includes control of receivables and avoidance of losses through inappropriate credit and collection procedures. Accounting control includes planning and controlling inventories, preventing disruption of production schedules and shipments or losses from scrap and obsolescence. It involves generating all the necessary facts on the performance of all functions such as manufacturing, research, engineering, marketing, and financial activities. It is mandatory that management be informed about the utilization of labor and material against a plan in producing the finished goods. The effectiveness of the sales effort in each territory or for each product must be subjected to review by management. Control relates to every classification in the balance sheet or statement of financial position and to each item in the statement of income and expense. In short, accounting/statistical control extends to all activities of the business. The accounting system that includes the accounting controls when integrated with the operating controls provides a powerful tool for management to plan and direct the performance of the business enterprise.

Statistical control also may relate to the nonfinancial quantitative measurement of any business functions and their effect, for example, customer satisfaction, development time for new products, cycle time from receipt of customer order to delivery of product.

NEED FOR STANDARDS

As industry has developed, grown, and become more complex, the need for increased efficiency and productivity has become more imperative. The successful executives developed more effective means of regulating and controlling the activities. It is no longer sufficient just to know the cost to manufacture or sell. There is a real need to know if we are using the most economical manufacturing techniques and processes. The distribution and selling costs must be evaluated and measured against some predetermined factors. Performance measurement should be applied to all activities. It is essential that a yardstick of desirable or planned results be established against which actual results may be compared if the performance measurement is to be effective. It is natural to compare current performance with historical performance such as last month, last quarter, or last year. Such a comparison points out trends, but it also serves to perpetuate inefficiencies. This comparison only serves a useful purpose if the measuring stick or past performance represents effective and efficient performance. Furthermore, changes in technologies, price levels, manufacturing processes, and the relative volume of production tend to limit the value of historical costs in determining what current costs should be.

There certainly is a compelling need for something other than historical costs for the standard of performance. For planning and pricing, management needs cost information that is not distorted by defective material, poor worker performance, or other unusual characteristics. Scientific management recognizes the value and need for some kind of engineering standards to plan manufacturing operations and evaluate the effectiveness with which the objectives are being accomplished. Engineering standards, expressed in financial terms, become cost standards; these standards, based on careful study and analysis about what it should cost to perform the operations by the best methods, become a much more reliable yardstick with which to measure and control costs.

Standards are the foundation and basis of effective accounting control. Standards provide the management tools with which to measure and judge performance. The use of standards is as adaptable to the control of income or expense as to the control of assets or liabilities. Standards are applicable to all phases of business and are an extremely important management tool.

DEFINITION OF STANDARDS

A standard of any type is a measuring stick or the means by which something else is judged. The standard method of doing anything can usually be described as the best method devised, as far as humanly possible, at the time the standard is set. It follows that the standard cost is the amount that should be expended under normal operating conditions. It is a predetermined cost scientifically determined in advance, in contrast to an actual or historical cost. It is not an actual or average cost, although past experience may be a factor in setting the standard.

Since a standard has been defined as a scientifically developed measure of performance, it follows that at least two conditions are implied in setting the standard:

- Standards are the result of careful investigation or analysis of past performance and take into consideration expected future conditions. They are not mere guesses; they are the opinions, based on available facts, of the people best qualified to judge what performance should be.

- Standards may need review and revision from time to time. A standard is set on the basis of certain conditions. As these conditions change, the standard must change; otherwise, it would not be a true measuring stick. Where there is really effective teamwork, and particularly, where standards are related to incentive payments, the probability of change is great.

Most of the foregoing comments on standards relate to that phase of the definition on which there is general agreement. There are, however, differences of opinion that seem to relate principally to the following points:

- Whether a standard should be (1) a current standard, that is, one that reflects what performance should be in the period for which the standard is to be used, or (2) a basic standard, which serves merely as a point of reference.

- The level at which a standard should be set—an ideal level of accomplishment, a normal level, or the expected level.

Where standard costs are carried into the formal records and financial statements, the current standard is generally the one used. Reference to the variances immediately indicates the extent to which actual costs departed from what they should have been in the period. A basic standard, however, does not indicate what performance should have been. Instead, it is somewhat like the base on which a price index is figured. Basic standards are usually based on prices and production levels prevailing when the standards are set. Once established, they are permanent and remain unchanged until the manufacturing processes change. They are a stationary basis of measurement. Improvement or lack of improvement involves the comparison of ratios or percentages of actual to the base standard.

The level at which standards should be set is discussed later in this chapter under the subject of standards for cost control.

ADVANTAGES OF STANDARDS

It has already been mentioned that standards arose, as part of the scientific management movement, from the necessity of better control of manufacturing costs. The relationship between this need and the advantages of standards is close. However, the benefits from the use of standards extend beyond the relationship with cost control to all the other applications, such as price setting or inventory valuation. Therefore, it may be well to summarize the principal advantages of standards, and the related scientific methods, by the four primary functions in which they are used:

- Controlling costs

- Standards provide a better measuring stick of performance. The use of standards sets out the area of excessive cost that otherwise might not be known or realized. Without scientifically set standards, cost comparison is limited to other periods that in themselves may contain inefficiencies.

- Use of the “principle of exception” is permitted, with the consequent saving of much time. It is not necessary to review and report on all operations but only those that depart significantly from standard. The attention of management may be focused on those spots requiring corrective action.

- Economies in accounting costs are possible. Clerical costs may be reduced because fewer records are necessary and simplified procedures may be adopted. Many of the detailed subsidiary records, such as production orders or time reports, are not necessary. Again, if inventories are carried as a standard value, there is no need to calculate actual costs each time new lots are made or received. Still further, much of the data for month-end closing can be set up in advance with a reduction in peak-load work.

- A prompter reporting of cost control information is possible. Through the use of simplified records and procedures and the application of the exception principle, less time is required to secure the necessary information.

- Standards serve as incentives to personnel. With a fair goal, an employee will tend to work more efficiently with the consequent reduction in cost. This applies to executives, supervisors, and workers alike.

- Setting selling prices

- Better cost information is available as a basis for setting prices. Through the use of predetermined standards, costs are secured that are free from abnormal distortions caused by excess spoilage and other unusual conditions. Furthermore, the use of standard overhead rates eliminates the influence of current activity. A means is provided to secure, over the long run, a full recovery of overhead expenses, including marketing, administrative, and research expense.

- Flexibility is added to selling price data. Through the use of predetermined rates, changes in the product or processes can be quickly reflected in the cost. Furthermore, adjustments to material prices or labor rates are easily made. Again, the use of standards requires a distinction between fixed and variable costs. This cost information permits cost calculations on different bases. Since pricing is sometimes a matter of selection of alternatives, this flexibility is essential.

- Prompter pricing data can be furnished. Again, the use of predetermined rates permits the securing of information more quickly.

- Valuing inventories

- A “better” cost is secured. Here, too, as in pricing applications, a more reliable cost is secured. The effect of idle capacity, or of abnormal wastes or inefficiencies, is eliminated.

- Simplicity in valuing inventories is obtained. All like products are valued at the same cost. This not only assists in the recurring monthly closings but also is an added advantage in pricing the annual physical inventory.

- Budgetary planning

- Determination of total standard costs is facilitated. The standard unit costs provide the basic data for converting the sales and production schedules into total costs. The unit costs can readily be translated into total costs for any volume or mixture of product by simple multiplication. Without standards, extensive analysis is necessary to secure the required information because of the inclusion of nonrecurring costs.

- The means is provided for setting out anticipated substandard performance. A history of the variances is available, together with the causes. Since actual costs cannot be kept exactly in line with standard costs, this record provides the basis for forecasting the variances that can reasonably be expected in the budget period under discussion. This segregation permits a determination of realistic operating results without losing sight of unfavorable expected costs.

RELATIONSHIP OF ENTITY GOALS TO PERFORMANCE STANDARDS

Much of the discussion in this chapter relates to detailed performance measures or standards. However, prior to any review of such standards, a key relationship to certain company goals or broad financial standards should be emphasized.

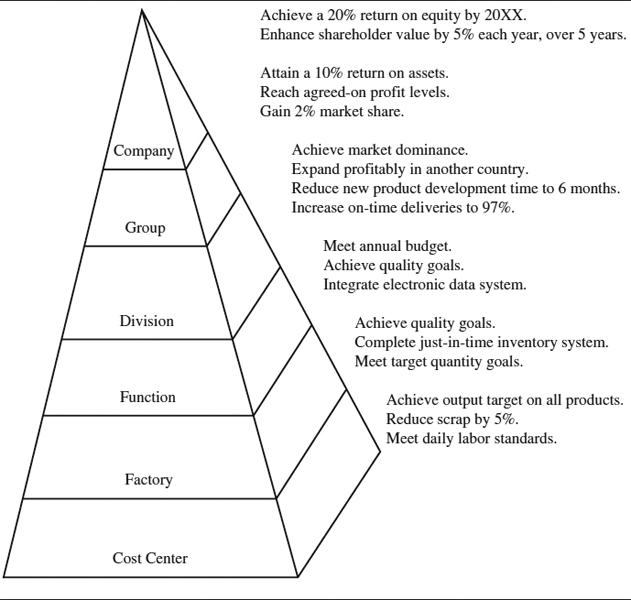

Some of the overall financial goals for a business include (1) measures of profitability, such as return on shareholder equity, return on assets, return on sales; (2) measures of growth, such as increase in sales, increase in net income, and increase in earnings per share; and (3) cash flow measures, including aggregate operating cash flow or free cash flow. But is there, or should there be, any relationship between such overall goals, which are a type of standard, and more specific performance measures, such as the direct labor hour standard in cost center 21 for manufacturing product A? A business usually has goals or objectives as well as strategies for reaching them. It is only logical, therefore, that the goals or standards of a cost center, or factory, or function or division, support the entity goals. The hierarchy of goals, or performance measures or standards, may be pictured as a pyramid. (See Exhibit 1.1.)

In examining performance measures, beginning at the top of the pyramid (company goals) and moving down the structure, these characteristics exist (although not all are identified):

- Performance measures usually become narrower and more specific.

- The planning horizon becomes shorter.

- In the lower levels, cost factors tend to dominate more; and the measurement or activity period shortens considerably from years to months, days, or even hours.

EXHIBIT 1.1 HIERARCHY OF PERFORMANCE MEASURES

Performance measures at the lower levels should be expressed in terms of what an individual employee can do. For example, an accounts payable clerk might have as a standard the number of invoices processed per day or the number of cash discounts taken (or lost). This activity level performance cannot be directly measured against a percent return on assets goal.

As the standards are expressed in terms of smaller, specific tasks, the time span between assigning the task, accomplishing the task, and rewarding the employee should grow shorter.

Care should be taken that objectives at the lower levels are not contradictory. For example, encouraging higher throughput should not be at the expense of causing excess inventories in another department. A given individual, cost center, or department should not be overpowered by having to meet too many different standards. Standards should be current; that is, they should relate to the processes or methods in use—not obsolete ones. They should be updated minimally each year, ideally, each quarter.

Formulating consistent standards that move the company objective forward takes a great deal of thought and time and is a management task of great importance.

TYPES OF STANDARDS NEEDED

Standards for All Business Activity

Managerial control extends to all business functions including selling, production, finance, and research. It would appear highly desirable, therefore, to have available standards for measuring effort and results in all these activities. The word standard in much of the accounting literature applies to manufacturing costs. But the fact remains that the principles underlying the development of standards can and should be applied to many nonmanufacturing functions. Business executives generally do not question the need or desirability of standards for the control of administrative, distribution, and financial activities; they do, however, recognize the difficulties involved. Some activities are more susceptible to measurement than others, but application of some standard is generally possible. Moreover, as business processes change, some performance standards will increase in importance, while others will decrease, for example, the use of a labor standard in which “direct” labor is less crucial and will be combined with related service support labor standards such as inspection or quality control.

Standards for Individual Performance

Costs are controlled by people. It is through the action of an individual or group of individuals that costs are corrected or reduced to an acceptable level. It is by the efforts of the individual salesperson that the necessary sales volume is secured. It is largely through the operational control of the departmental foreperson that labor efficiency is maintained. As a result, any standards, to be most effective, must relate to specific phases of performance rather than merely general results. In a manufacturing operation, for example, standards should relate to the quantity of labor, material, or overhead in the execution of a particular operation rather than the complete product cost standard. In the selling field, a sales quota must be set for the individual salesperson, perhaps by product, and not just for the branch or territory.

Thus the setting of standards and measurement of performance against such yardsticks fit into the scheme of “responsibility accounting.”

Keeping in mind these general comments, specific types of standards can now be examined. In addition to the remarks in this chapter, further observations are made in some of the chapters in which the relevant function is reviewed.

Material Quantity Standards

In producing an article, one of the most obvious cost factors is the quantity of material used. Quantitative standards, based on engineering specifications, outline the kind and quantity of material that should be used to make the product. This measuring stick is the primary basis for material cost control. This quantity standard, when multiplied by the unit material price standard, results in the cost standard. When more than one type of material is involved, the sum of the individual material cost standards equals the total standard material cost of the product.

Material Price Standards

To isolate cost variances arising out of excess material usage from those arising because of price changes, it is necessary to establish a material price standard. Usually, this price standard represents the expected cost instead of a desired or “efficient” cost. In many companies, this price is set for a period of a year, and, although actual cost may fluctuate, these changes are not reflected in the standard unit cost of material used. In other words, every piece of material used is charged with this predetermined cost.

Labor Quantity Standards

The labor content of many products is the most costly element. But whether it is the most costly or not, it is usually important. Because we are dealing with the human element, the labor cost is one of the most variable. It is indeed a fertile field for cost reduction and cost control.

For these reasons, it is necessary to know the amount of labor needed to produce the article. The technique, determining the time needed to complete each operation when working under standard conditions, involves time and motion study.

Labor Rate Standards

The price of labor is generally determined by factors outside the complete control of the individual business, perhaps as a result of union negotiations or the prevailing rate in the area. In any event, it is desirable to have a fixed labor rate on each operation to be able to isolate high costs resulting from the use of an excess quantity of labor. Also, the utilization of labor within a plant is within the control of management, and some rate variances arise due to actions controllable by management. Examples are the assignment of the wrong people (too high a rate) to the job or the use of overtime.

The standard time required, when multiplied by the standard rate, gives the standard labor cost of the operation.

Manufacturing Overhead Expense Standards

One of the many problems most controllers must resolve is that of determining standards for the control of manufacturing overhead as well as absorption into inventory. The determination of these standards is somewhat more complicated than in the material or labor standards. Several conditions complicate their determination:

- Manufacturing overhead consists of a great variety of expenses, each of which reacts in a different fashion at varying levels of plant activity. Some costs, such as depreciation, remain largely independent of plant activity; others vary with changes in production, but not in direct proportion. Examples are supervisory labor, maintenance, and clerical expense. Still other overhead expense varies directly with, and proportionately to, plant volume. This may include certain supplies, indirect labor, and fuel expense.

- Control of overhead expenses rests with a large number of individuals in the organization. For example, the chief maintenance engineer may be responsible for maintenance costs, the factory accountant for factory clerical costs, and foremen in productive departments for indirect labor.

- The proper estimate of the rate and amount of production must be made to serve as the basis of setting standard rates. An improper level of activity not only affects the statement of income and expense, but also gives management an erroneous picture of the cost of an insufficient volume of business and distorts inventory values.

Overhead expenses are best controlled through the use of a flexible budget. It requires a segregation of fixed and variable expenses. Proper analysis and control permit a realistic look at overhead variances in terms of cause: (1) volume, (2) rate of expenditure, and (3) efficiency.

Standards for manufacturing overhead can be expressed in the total amount budgeted by each type of expense as well as unit standards for each item, such as power cost per operating hour or supplies per employee-hour. Such standards should reflect the impact of just-in-time (JIT) production techniques as well as the “cost drivers.”

Sales Standards

Sales standards may be set for the purpose of controlling and measuring the effectiveness of the sales or marketing operations. They also may be used for incentive awards, stimulating sales efforts, or the reallocation of sales resources. The most common form of standard for a territory, branch, or salesperson is the sales quota, usually expressed as a dollar of physical volume. Other types of standards found useful in managing and directing sales effort are:

- Number of total customers to be retained

- Number of new customers to be secured

- Number of personal calls to be made per period

- Number of telephone contacts to be made per period

- Average size of order to be secured

- Amount of gross profit to be obtained

Distribution Cost Standards

Just as production standards have been found useful in controlling manufacturing costs, so an increasing number of companies are finding that distribution cost standards are a valuable aid in properly directing the selling effort. The extent of application and degree of completeness of distribution cost standards will differ from production standards, but the potential benefits from the use of such standards are equally important.

Some general standards can be used in measuring the distribution effort and results. However, more effective standards are those measuring individual performance. Some illustrative standards are:

- Selling expense per unit sold

- Selling expense as a percentage of net sales

- Cost per account sold

- Cost per call

- Cost per day

- Cost per mile of travel

- Cost per sales order

In addition to individual performance standards, another type of control relates to budgets for selling expenses. The procedure for setting budgets is similar to that used for manufacturing operations.

Administrative Expense Standards

As business expands and volume increases, there is a tendency for administrative expenses to increase proportionately and get out of line. The same need for control exists for these types of expenses as for manufacturing or production costs. Control can be exercised through departmental or responsibility budgets as well as through unit or individual performance standards. The general approach to control administrative expenses is essentially the same as for control of selling and manufacturing expenses. It is necessary to develop an appropriate standard for each function or operation to be measured.

Examples of types of standards to be considered are:

| Function | Standard Unit of Measurement |

| Purchasing | Cost per purchase order |

| Billing | Cost per invoice rendered |

| Personnel | Cost per employee hired |

| Traffic | Cost per shipment |

| Payroll | Cost per employee |

| Clerical | Cost per item handled (filed) |

Financial Ratios

The types of standards discussed to this point relate primarily to human performance associated with elements of the statement of income and expense—sales revenues, cost factors, and expense categories of several types. Yet another category of standards deals with the utilization of assets or shareholders' equity, or the liquidity of the entity. These measures relating to financial condition and profitability rates are of special interest to the financial executives in testing business plans and the financial health of the enterprise.

A short list of some of the more important financial and operating ratios includes:

- Current ratio

- Quick ratio

- Ratio of net sales to receivables

- Turnover of inventory

- Turnover of current assets

- Ratio of net sales to working capital

- Ratio of net sales to assets

- Return on assets

- Return on shareholders' equity

- Other profitability ratios:

- Ratio of net income to sales

- Gross margin percentage

Generally speaking, the standards for these financial ratios may be developed from several sources:

- Ratios accepted by the industry of which the company is a member, perhaps developed by the industry association

- Ratios ascertained from the published financial statements of the principal competitors of the entity, or industry leaders

- Ratios developed by computer modeling

- Ratios based on the past (and best) experience of the company or on the opinions of its officers

TREND TO MORE COMPREHENSIVE PERFORMANCE MEASURES

The majority of the standards described relate to very specific activities and are largely cost standards (labor cost per unit). Additionally, some relate to number or size of functions per-formed (number of sales calls made), or financial relationships. It is common practice in U.S. companies to compare hourly, daily, weekly, or monthly actual performance with such a standard, or a budget, or prior experience. Such comparisons with the relevant internal activity of a prior period or calculated proper measure are useful.

Managements are discovering that other types of measures may be helpful for a number of reasons:

- Some non–cost-related measures can highlight functional areas that need improvement, for example, number of new customers, number of customer complaints, product development time.

- For some activities, comparisons with an external standard, such as industry average or performance of a principal competitor, may provide useful guidelines. Examples include inventory turnover and research and development expenditures.

- Quantified standards may cause supervisors to focus attention on the wrong objective. For instance, attention to the average size of sales orders may take attention away from the need for a profitable product mix.

- On occasion, emphasis on output can create problems in, or transfer problems to, other departments (defects, excessive inventory, or wrong mix of parts).

- Some standards may conflict with other management efforts, such as attempting to reduce indirect manufacturing expense as related to direct labor, when the overall trend is to automation.

In the search for a broader base than accounting or financial standards to check or measure company performance, the controller, perhaps in collaboration with other functional executives, could take these actions:

- Discuss with management members the critical success factors of the company, suspected areas of weaker performance, and what changes might be examined.

- Review existing performance measures and try to ascertain whether they are relevant to the newer techniques or processes (JIT purchasing, delivery and manufacturing).

- Seek to determine if the measures relate to the true cost drivers of the function under review.

- Update practices, using the current literature or periodicals for possible leads to examine.

- Talk with controllers, line managers, or workers, in other companies about the performance measures and other guides they use.

- Consider hiring outside consultants to review areas of suspected weaknesses and to make recommendations. Such a review might lead to a starting list of (1) cost measures and (2) noncost performance measures for important internal activity checking (based on trends and relative internal importance, and relative cost and noncost measures when examined or compared to external factors). A sample outline of what could be measured is:

- Internal Factors

- (a) Cost Measures

Direct labor costs

Direct material costs

Manufacturing expense

Marketing expense

Research and development (R&D) costs

Delivery costs

Inventory carrying costs

Accounts receivable carrying costs

- (b) Noncost Measures

Length of design cycle

Number of engineering changes

Number of new products

Manufacturing cycle time

Number of parts/raw material deliveries

Number of on-time customer deliveries

Number of suppliers

Number of parts

- (a) Cost Measures

- External Factors (Relative Measurement)

- (a) Cost Measures

Relative R&D expense

Relative material content cost

Relative labor cost content

Relative delivery expense

Relative selling expenses

- (a) Cost Measures

Time-Based Standards

One group of standards receiving attention are time-based measures. Management which uses these diagnostic tools believes that time analysis is more useful than simple cost analysis because activity review identifies exactly what occurs every hour of the working day. It seems to encourage such time-oriented questions as: Why are the two tasks done serially and not in parallel? Why is the process speeded up in some departments only to then let the product lie idle? When points of time are identified, then related cost reduction possibilities can be examined.

Examples of time-based standards that have been found useful in four key functions include:

- Decision-making process: Time lost in waiting for a decision

- Product development

- Manufacturing

- Marketing

- Finance (accounting)

- New product development

- Total time required from inception of idea to marketing of product

- Number of times (or percent) company has beat a competitor to market

- Number of new products marketed in a given time period

- Manufacturing or processing

- Cycle time from commencement of manufacture through billing process

- Inventory turnover

- Total elapsed time from product development to first time acceptable output

- Value added per factory hour

- Credit approval time

- Billing cycle time—from receipt of shipping notice to completion of invoice preparation

- Collection time—from mailing of invoice to receipt of payment

- Customer service

- Number (or percent) of on-time deliveries

- Response time to customer questions

- Quoted lead time for shipment of spare parts, repairs, and product delivery

- Delivery response time

BENCHMARKING

The practice by a company of measuring products, services, and business practices against the toughest competitor or those companies best in its class, or against other measures, has been named “benchmarking.” Technically, those who consult about the process differentiate between three kinds, depending on the consultant. Distinctions are made about these three types:

- Competitive benchmarking

- Noncompetitive benchmarking

- Internal benchmarking

Competitive benchmarking studies compare a company's performance with respect to customer-determined notions of quality against direct competitors.

Noncompetitive benchmarking refers to studying the “best-in-class” in a specific business function. For example, it might encompass the billing practices of a company in a completely different industry.

Internal benchmarking can refer to comparisons between plants, departments, or product lines within the same organization. The benchmarking studies involve steps such as:

- Determining which functions within the company to benchmark

- Selecting or identifying the key performance variables that should be measured

- Determining which companies are the best-in-class for the function under review

- Measuring the performance of the best-in-class companies

- Measuring the performance of the company as to the function under study

- Determining those actions necessary to meet and surpass the best-in-class company

- Implementing and monitoring the improvement program

Although benchmarking has produced some legendary corporate successes, it often has not produced an improvement on the net income line. In part, this reflects the fact that it is a complicated process and does not consist merely of some random observations of different methods used by some businesses, or some short field trips. A successful benchmarking effort must be undertaken in a clearly defined and systematic manner. A benchmarking study wherein the only product or result is a report to management, with no modification of a substandard activity, could be regarded as a failure.

To put the topic of benchmarking in the proper perspective, it should be recognized that successful benchmarking efforts have addressed a wide variety of issues, including:

- Increased market share

- Improved corporate strategy

- Increased profitability

- Streamlined processes

- Reduced costs

- More effective R&D activities

- Improved quality

- Higher levels of customer satisfaction

In those instances when benchmarking activity has not met expectations, some of the reasons include:

- Top management did not comprehend the full potential of the proposed changes and consequently did not push aggressively for their adoption.

- The functions or activities selected for improvement may in fact have been improved, but the greater efficiency was too small to have a meaningful impact on overall business performance.

- The study team made observations but failed to develop an actionable plan.

- In some instances, the analysis was incomplete: the study team learned what the best-in-class companies were doing, but it did not learn how the actions were implemented.

Another facet of benchmarking that should be noted is the makeup of the study team. It should include people in the company who have been performing the function. Those selected should be highly knowledgeable about the function, should be good communicators, and should be curious and highly analytical. It probably is preferable to have consultants, not company employees, make contacts with competitors. In some circumstances, the presence of a member of the board of directors might be the means of better communicating to the board the complexities and potential impact of the study. In summary, benchmarking is a complicated process, and full preparation should be made.

BALANCED SYSTEM OF PERFORMANCE MEASURES

Performance measures range from broad company standards to detailed functional standards applied to a daily departmental manufacturing activity. Moreover, many of these standards are used for both planning and control purposes. Then, too, some are cost-related and others are noncost measures; some address the important subject of customer satisfaction, and others simple efficiency; and finally, some deal with innovation while others emphasize routine operations.

Many years ago, the use of one type of standard (generally cost type) for control purposes was the point of emphasis. Since that time, management has recognized that it cannot rely on one set of measures to the exclusion of all others. Rather, a combination of measures are necessary that must properly relate to each other and take into account the critical success factors of the enterprise. This is to say that management needs a balanced set of performance measures.

The article by Kaplan and Norton mentions a company that grouped its performance measures into four types, each with separate measures of performance, and each critical to the future success of the entity.1

The four measurement groups discussed, together with some added goals and measures of individual performance mentioned earlier in this chapter follow.

SETTING THE STANDARDS

Who Should Set the Standards?

Standards should be set by those who are best qualified by training and experience to judge what good performance should be. It is often a joint process requiring cooperation between the staffs of two or more divisions of the business. Fundamentally, the setting of standards requires careful study and analysis. The controller and staff, trained in analysis and possessing essential records on the various activities, are in an excellent position to play an important part in the establishment of yardsticks of performance.

Since standards are yardsticks of performance, they should not be set by those whose performance is to be measured. Sufficient independence of thought should exist. The standards should be reviewed with those who will be judged by them and any suggestions considered. However, final authority in establishing the standard should be placed in other hands.

Exactly which staff members cooperate in setting standards depends on the standards under consideration. Material quantity standards, for example, are generally determined by the engineers who are familiar with the operation methods employed as well as the product design. Assisting the engineers may be the production staff and the accounting staff. The production people can make valuable contributions because of their knowledge of the process. Furthermore, permitting the production staff to assist usually enlists their cooperation in making the standards effective. The accounting department assists by providing necessary information on past experience.

The determination of material price standards is usually the responsibility of both the purchasing and accounting departments. The purchasing department may indicate what expected prices are. These should then be challenged by the accounting department, taking into account current prices and reasonably expected changes. In other instances, the accounting department sets the standards, based again on current prices, but takes into consideration the opinion of the purchasing department about future trends.

Quantitative labor standards are usually set by industrial engineers through the use of time and motion study. This is properly an engineering function in that a thorough background of the processes is necessary. On occasion, the accounting department furnishes information of past performance as a guide. Standard labor rates are set by the department that has available the detailed job rates and other necessary information, typically the cost department. The cost department must also translate the physical standards into cost standards.

Manufacturing overhead standards, too, are often a matter of cooperation between the accounting and engineering departments. Engineers may be called on to furnish technical data, such as power consumption in a particular department, or maintenance required, or type of supplies necessary. However, this data is then costed by the accounting staff. In other instances, the unit standards or budgets may be set in large part on past experience. The role played by the accountant tends to be much greater in the establishment of overhead standards due to the familiarity with the techniques of organizing the data into their most useful form for cost and budget reporting. Setting the standards for distribution activities is best done through the cooperation of sales, sales research, and accounting executives. Reliance is placed on the sales staff for supplying information pertaining to market potentials and sales methods. The accountant contributes the analysis and interpretation of past performance, trends, and relationships. The sales and accounting executives jointly must interpret the available data as applied to future activity.

Unit standards for the measurement of administrative expenses are usually determined on the basis of time and motion study by industrial engineers, observation of the functions, or a detailed analysis of past performance to ensure that standards reflect the norm. In many instances, the accountant is involved in either costing the data or analyzing past experience.

Financial and operating ratios should be set by the controller based on the objectives for the company, experience in the particular company or industry, and special analysis or consideration of factors that have a significant influence on the ratio or external sources.

In many instances, it may be desirable to have the assistance of independent consultants. For example, when sources outside the company are to be contacted, as in “benchmarking,” these noncompany personnel may be especially helpful.

Method of Setting Standards

Those aspects of setting standards that are beyond the sphere of accounting responsibility are adequately covered in various management and engineering literature. Only the general steps taken in the establishment of standards will be considered here. Any outline of procedure regarding standards is basically only the application of logic and prudent judgment to the problem. The eight phases involved in the setting of standards are summarized below:

- Recognition of the need for a standard in the particular application. Obviously, before action is taken, the need should exist. This need must be acknowledged so that the problem can be attacked.

- Preliminary observation and analysis. This involves “getting the feel” of the subject, recognizing the scope of the problem, and securing a general understanding of the factors involved.

- Segregation of the function, or activity, and/or costs in terms of individual responsibility. Since standards are to control individual actions, the outer limits of the respon-sibility of each individual must be ascertained in the particular application.

- Determination of the unit of measurement in which the standard should be expressed. To arrive at the quotient, the divisor is necessary. And in many applications, the base selected can be one of many.

- Determination of the best method. This may involve time and motion study, a thorough review of possible materials, or an analysis of past experience. It must also involve consideration of possible changes in conditions.

- Statement or expression of the standard. When the best method and the unit of measurement have been determined, the tentative standard can be set.

- Testing of the standard. After analysis and synthesis and preliminary determination, the standard must be tested to see that it meets the requirements.

- Final application of the standard. The testing of a standard will often result in certain compromises or changes. When this has been effected, when the best judgment of all the executives concerned has been secured, then and only then can the standard be considered set and ready to be applied.

USE OF STANDARDS FOR CONTROL

The fact that management has set standards for cost control by no means assures control of costs. It takes positive action by individuals to keep costs within some predetermined limits. It is a management challenge to communicate the value of standards to all concerned and convince them how the yardsticks can be utilized in accomplishing the goals and objectives. To be effective it must be demonstrated that the standards are fair and reasonable.

The controller must have sufficient facts to illustrate the reasonableness of the standards when questions arise or the yardsticks are considered unfair.

When standards are shown clearly to be unreasonable, the controller must be prepared to gather new data and make appropriate adjustments.

Technique of Cost Control

In the final analysis, the objective of cost control is to secure the greatest amount of production or results of a desired quality from a given amount of material, manpower, effort, or facilities. It is the securing of the best result at the lowest possible cost under existing conditions. In this control of performance, the first step is the setting of standards of comparison; the next step is the recording of actual performance, and the third step is the comparing of actual and standard costs as the work progresses. This last step involves:

- Determining the variance between standard and actual

- Analyzing the cause of the variance

- Taking remedial action to bring unfavorable actual costs in line with the predetermined standards

Control is established through prompt follow-up, before the unfavorable trends or tendencies develop into large losses. It is important that any variances be determined quickly, and it is equally important that the unfavorable variance be stated in terms that those responsible will understand. The speed and method of presentation have a profound bearing on the corrective action that will be taken and, hence, on the effectiveness of control.

Role of Statistical Process Control

One approach to cost control is to determine the variance between a standard and actual performance, seek out the cause of the variance, and take remedial action. Yet global competition is causing management to adopt more sophisticated strategies to remain or become competitive. Among these devices are automatic JIT, total quality management (TQM), and statistical process control (SPC). This latter technique can assist in properly setting standards and in better evaluating or interpreting variances. SPC is based on the assumption that process performance is dynamic, that variation is the rule. Consequently, proper assessment of performance requires correct interpretation of the variation over a period of time. Charts or graphic aids are used in SPC to understand and reduce the fluctuations in processes until they are considered stable (under control). A stable process would have only the normal variances. On the other hand, an unstable process is subject to uncommon fluctuations resulting from special causes. The performance of a stable process can be improved only by making fundamental changes in the process itself, while an unstable production process can be stabilized only by locating and eliminating the special causes. The statistical approach assists in identifying the character of the variance. An incorrect decision that a process is operating in an unstable manner may result in costs from searching for special causes of process variation that do not exist. An incorrect decision that a process is operating in a stable manner will result in failure to search for special causes that do exist.

Suffice it to say that SPC is a complex subject that seeks to provide long-term solutions. Someone with a high level of statistical knowledge ordinarily will be needed to assist in implementing the strategy. Management accountants should understand the SPC approach.

Who Should Control Costs?

Costs must be controlled by individuals, and the question is raised about who should control costs, the controller representing accounting personnel or the operating executive in charge of the activity (manufacturing sales or research) to be cost controlled. It has already been explained that operational control preceded accounting control. In many thousands of small businesses, operating control is the only type used. Cost control is not primarily an accounting process, although accounting plays an important part. Control of costs is an operating function. The controller, in the capacity of an operating executive, may control costs within the accounting department. Beyond this, the function of the controller is to report the facts on other activities of the business so that corrective action may be taken and to inform management of its effectiveness in cost control. The part played by the controller is advisory or facilitative in nature.

In many instances, the development of the standards to be used in measuring performance is largely the work of nonaccountants, whether product specifications, operational methods, time requirements, or other standards. Likewise, decision about the corrective action to be taken is generally up to the operating personnel. However, the controller is in an excellent position to stimulate and guide the interest of management in the control of costs through the means of reports analyzing unusual conditions. The controller's work is usually confined to summarizing basic information, analyzing results, and preparing intelligently conceived reports. It follows that the controller must produce reports that a non–accounting-trained executive or operator can understand and will act on. To do this requires being thoroughly conversant with the operating problems and viewpoints. The effectiveness of any cost control system depends on the degree of coordination between the accounting control personnel and the operating personnel. One presents the facts in an understandable manner; the other takes the remedial action.

Cooperation at all levels is essential in the control of costs. Cooperation is secured, in part, through the application of correct management policies. The use of standards, when fully understood, should be of great assistance in securing this cooperation, for the measuring stick is based on careful analysis and not preconceived ideas or rule-of-thumb methods.

Level of the Standard

Because one of the primary purposes of a standard is as a control tool—to see that performance is held to what it should be—it is necessary to determine at what level the standard should be set. Just how “tight” should a standard be? Although there is no clear-cut line of demarcation among them, the three following levels may be distinguished:

- The ideal standard

- The average of past performance

- The attainable good performance standard

The ideal standard is the one representing the best performance that can be attained under the most favorable conditions possible. It is not a standard that is expected to be attained but rather a goal toward which to strive in an attempt to improve efficiency. Hence variances are always unfavorable and represent the inability to reach the ideal level of efficiency. The use of an unattainably tight standard confuses the objectives of cost reduction and cost control. Cost reduction involves the finding of ways and means to achieve a given result through improved design, better methods, new layouts, new equipment, better plant layout, and so forth, and therefore results in the establishment of new standards. If the standards set are more restrictive than currently attainable performance, the lower cost will not necessarily be achieved until cost reduction has found the means by which the standard may be attained. Ideal standards, then, are not highly desirable as a means of cost control.

Standards are frequently set on the basis of what was done in the past, without adjustments to reflect improved methods or elimination of wastes. A standard set on this basis is likewise a poor measuring stick in that it can be met by poor performance. Hence the very inefficiencies that standards should disclose are obscured by the loose standard.

A third level at which a standard may be set is the attainable level of good performance. This standard includes waste or spoilage, lost time, and other inefficiencies only to the extent that they are considered impractical of elimination. This type of standard can be met or bettered by efficient performance. It is a standard set at a high level but is attainable with reasonably diligent effort. Such a standard would seem to be the most effective for cost control purposes.

Point of Control

Costs are controlled by individuals, so it follows that the accounting classifications must reflect both standard and actual performance in such a manner that individual performance can be measured. As stated previously, “responsibility accounting” must be adopted. Provision must be made for the accumulation of costs, by cost centers, cost pools, or departments, that follows organizational structure. Furthermore, this cost accumulation must initially reflect only those costs that are direct as to the specific function being measured. Allocations and reallocations may be made for product cost determination and for certain other planning applications, but this is not desirable for cost control. If a great many prorations are made, it is often difficult to determine where the inefficiency exists or the extent of it. Therefore, it is desirable from a cost control standpoint to collect the costs at the point of incurrence.

If, as in some companies, allocated costs are reflected in control reports, it is desirable to separate them from direct expenses or costs. Some companies show allocated costs so that the department manager will be aware of the cost of the facilities or services they use.

Discussion of the point of control of costs involves, in addition to placement of responsibility, the matter of timing. Costs must be controlled not only at the point of incurrence but also, preferably, at or before the time of incurrence. Thus, if a department on a budget basis processes a purchase requisition and is advised at that time of the excess cost over budget, perhaps action can be taken then—either delaying the expenditure until the following month or getting a less expensive yet satisfactory substitute. Again, material control is best exercised at the point of issuance. Only the standard quantity should be issued. In the case of purchases, the price and type are best controlled at the time of purchase.

What Costs Should Have Standards?

From the viewpoint of standards for cost control, a question may be raised about the extent to which attempts should be made to set standards. Factors to be considered include the relative amount of cost and the degree of control possible over the cost.

It may be stated that standards should be set for all cost items of a significant or material amount. In many cases, the more important the cost, the greater is the opportunity or need for cost control. With such items as overhead, it may be necessary to combine certain elements but, so far as practicable, a standard should be set to measure performance.

Another factor to be considered is the degree of control possible, needed, or desired over the cost. At first, it might appear that little control can be exercised over some types of cost, such as depreciation, salaries of key personnel, or personal property taxes. However, the fact is that most costs can be controlled by someone. The time and place and method of control of costs generally considered as “fixed” may differ from the control of material, direct labor, or variable overhead expense, but a certain degree of control is possible. Control of the fixed charges may be exercised in at least two ways:

- By limiting the expenditure to a predetermined amount. For example, depreciation charges are controlled through the acquisition of plant and equipment. Any control must be exercised at the time of purchase or construction of the asset. This is usually done by means of an appropriation budget, which is a type of standard. A similar plan can be applied to the group of salaried personnel generally considered as a part of the fixed charges. In many instances, control of this type of expense or expenditure is a top-management decision. It may be observed, however, that control at this high level does exist.

- By securing the proper utilization of the facilities and organization represented by the fixed charges. The controller can assist in this task by properly isolating the volume costs or cost of idle equipment. An acceptable standard might be the percent of plant utilization as related to “normal.” In the monthly statement of income and expense, the lack of volume costs should be set out as part of the effort to direct management's attention to the excess costs and to a consideration of ways and means of reducing personnel, if necessary, or increasing volume through other products, intensified sales activity, and so on.

PROCEDURE FOR REVISING STANDARDS

Revision of Standards

Whether standards are used for cost control or the related function of budgetary planning or whether standards are for the purpose of price setting or inventory valuation, they must be kept up to date to be most useful. From a manufacturing operations viewpoint, revision appears desirable when important changes are made in material specifications or prices, methods of production, or labor efficiency or price. Changes in the methods or channels of distribution and basic organizational or functional changes would necessitate standard changes in the selling, research, or administrative activities. Stated in other terms, current standards must be revised when conditions have changed to such an extent that the standard no longer represents a realistic or fair measure of performance.

It is obvious that standard revisions should not be made for every change, only the important ones. However, the constant search for better methods and for better measurements of performance subjects every standard to possible revision. The controller constantly must be on the alert about the desirability of adjusting standards to prevent the furnishing of misleading information to management.

Program for Standard Revision

The changing of standards is time consuming and may be expensive. For this reason, it should not be treated in a haphazard manner. It is desirable to plan in advance the steps to be taken in revising standards. Through the use of an orderly program for constant review and revision of standards, the time and money spent on standard changes can be less and the effort more productive.

In planning the program of standard revision, the ramifications of any changes should be considered. For example, changes in manufacturing standards usually necessitate changes in inventory values. Accordingly, it may appear desirable to review the standards at the end of each fiscal year and make the necessary changes. A chemical plant may review material price standards every quarter because the selling price of the finished product is sympathetic to changes in commodity prices. This frequent revision would result in cost information that is more useful to the sales department. In some companies, a general practice is to change standards whenever basic selling price changes occur. This results in a more constant standard gross profit figure by which to judge sales performance. In considering frequent changes, however, the expense should be weighed against the benefits. In this connection, the value for cost control should be matched against the lessened degree of comparability of the variances from period to period.

Judgment should be exercised about the necessity for, and extent of, changes in the records. For example, general changes in labor rates, raw material costs, standard overhead rates, or product design may dictate a complete revision of product and departmental costs, extending through every stage of manufacture. However, a change in one department, or in one part, or in a small assembly might necessitate the change of only one standard for control purposes. The difference between old and new, with respect to other stages of manufacture, or the finished product cost, could be temporarily written off as a variance until the time is ripe for a complete product standard revision.

RECORDING STANDARDS

Importance of Adequate Records

If the controller is to serve management most effectively and if the business is to have the advantage of accurate, reliable, and prompt cost information, then an adequate recording of the facts is necessary. This principle is as applicable to recording standards and standard costs as it is to actual costs—perhaps even more so. The degree of intelligence applied to the form and method of recording determines in large measure that:

- The data underlying the development and revision of standards will be available as needed.

- The facts relating to operating efficiency will be ascertainable and accurately analyzed.

- The information will be made available on an economical basis.

- The records will have the necessary flexibility to meet promptly the needs of the various applications of the standards.

Types of Records Necessary

In the manufacturing function, the records incident to the establishment and use of standards may be classified into four basic groups:

- Physical specifications that outline the required material and the sequence of manufacturing operations that must be performed

- Details of standard or budgeted overhead based on normal capacity

- Standard cost sheets for each product and component part, which indicate standard cost by elements

- Variance accounts that indicate the type of departure from standard

The extent and form of these records depend on the size and characteristics of the business. In an assembly type operation, for example, there would be a product specification for each part. These, in turn, would form the basis for cost sheets on subassemblies and assemblies. In most cases this data would be recorded, accumulated, stored, and reported through the integrated computer processing system. This would include information from the production order, standard labor hours for each operation, and the ability to calculate the standard cost of each part and assembly. With the details of standards available, changes are easily made for substitution of parts in determining the standard cost of modifications of a basic product. Standards are equally applicable to processing operations like the chemical industry—the key is setting fair and reasonable standards for each operation or process and making adjustments for changed conditions.

Administrative Controls

Although the use of standards is not as well developed for administrative functions as for manufacturing operations, yardsticks can be established for such usage in most cases. Some companies collect and analyze statistical data from which some performance measurements can be made. The controller should continue to evaluate these functions to determine the best method or standard against which actual performance can be compared.

Incorporation of Standard Costs in Accounts

Historically, some companies use standard costs for statistical comparisons only and do not incorporate them into the accounting record system. This is probably more true for administrative-type expenses than for direct manufacturing costs. With the data storage and processing capabilities of computers, it appears essential that the standard cost records be integrated into the accounting system. This will result in better cost control, inventory valuation, budgeting, and pricing.

APPLICATION OF STANDARD COSTS

Even though standard costs are incorporated in the accounts, there is considerable difference about the period in the accounting cycle when the standards should be recorded. Whereas there are several variations in accounting treatment, the distinction may be twofold:

- Recognition of the standard cost at the time of cost incurrence

- Recognition of the standard cost at the time of cost completion

The first method charges work in progress at standard cost, whereas the second method develops the standard cost at the time of transfer to the finished goods account. Recognition of costs at incurrence would imply a recording of material price variance at the time of purchase and material usage variance at the time of usage or transfer to work in process. However, many firms record material at actual cost and recognize price variances only as the material is used. This practice permits a write-off of excess costs proportionate to usage so that unit costs tend to approximate the actual cost each month.

MANAGEMENT USE OF STANDARD COSTS

Extensive use of standard cost data can be made by management in directing the activities of the company. Some areas to be considered are:

- Planning and forecasting

- Motivation of employees

- Rewarding employees

- Performance measurement

- Analyzing alternative courses of action—new products

- Pricing decisions

- Inventory valuation

- Make or buy decisions

- Control and cost reduction

1. Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton, “The Balanced Scorecard—Measures That Drive Performance,” Harvard Business Review, Jan.–Feb. 1992, pp. 71–79.