Chapter 3. ECM Stack: Content Control

After content is in the system, it’s time to put it to work. You might think this is the easy part. Functionally, it is much easier than the creation and capture portions of the ECM life cycle, but strategically, it’s very difficult. We have found many organizations that are several years past an initial SharePoint deployment looking back and realizing that the adoption of this technology has not really improved a business process. In many cases, it has either become a web version of a shared drive silo or a collection of mismatched sites that aren’t easily navigated by users.

As we mentioned in Chapter 1, an ideal EMC solution is a balance between the effort to capture content and the effort to consume or find content. The preceding chapter was all about getting content into SharePoint; this chapter is all about consumption and accessing the content you need in an intuitive and structured manner. After content is stored in SharePoint, you have to pay particular attention to how content is managed, who manages that content, and how the content will be delivered and consumed. Last but not least, you need to determine how the content completes its life cycle, through disposition or long-term preservation.

Management of content

When we talk about the management of content, we are not just referring to who is in charge of SharePoint. Yes, we will discuss how to make sure your content is being treated properly. But we are also talking about how to manage its value, the people who use it, and setting proper expectations.

Two extremes prevail when organizations start implementing SharePoint. It either is seldom used, or it’s used prolifically without governance. Being aware of both of these opposing outcomes will guide your ECM team’s planning and help determine where to focus their primary efforts. You can start by answering the following four questions:

Being honest about whether or not your organization can embrace new technology is an important question. In general, younger organizations are more adept and open to change, adopting new technologies, and improving processes. This is also true about people, so being realistic about who, where, and how you will implement and be successful with change is vitally important. Be aware of signals that people are resistant to change. These signals can come in the form of availability for meetings, a consistent focus on exception processing during design meetings, and the use of phrases like “If it isn’t broke, don’t fix it” or “This is how we have always done it.”

It’s important to work within the confines of how your organization adopts and addresses change. Specifically, in question 2, we ask whether your organization processes work at a micro or macro level. What we mean is this: How are decisions made, and who can effect change in work processes most effectively? In some organizations, groups and departments are given a fair amount of autonomy to get work done in the most efficient manner, using the tools and techniques that suit them best. In other more structured organizations, everything is mandated from the top down and there is a great deal of command and control.

Depending on your situation, you need to know how and where to start scoping the management aspects of content in your SharePoint ECM solution. This will also help you determine what individuals need to be on the ECM team, which we will cover in Chapter 5.

Change opposition or support

We implied earlier that ECM is as much, if not more, of a people problem as it is a technology problem. Although we use common nomenclature for business processes, like “expense approval,” and for departments, like “accounting,” no two organizations are alike. Because of this, it’s important to use principles and methods to guide your ECM solution design and not necessarily defined steps or configuration outlines.

We have found that there are companies who love new technology and, as an aspect of the culture, cannot wait to get their hands on it. These types of organizations or groups will be very excited to start using SharePoint and will be your early adopters. You can leverage their enthusiasm, but you will need to contain it, because this is usually the beginning of how viral use of SharePoint starts. Without Information Architecture (IA) or governance, these users will adopt bad habits and the ECM solution will turn out poorly. When this group establishes a bad habit, it’s hard to stop it.

You might find that the organization in its entirety or in specific groups is very used to process and control. These control-conscious groups are welcoming and normally not opposed to systematic ways to organize information. If you look at their shared drives, they tend to be very organized already, which we hinted could help with IA planning we cover in Chapter 4. While this group will be great for adopting SharePoint for ECM in the correct way, they will be hard to get moving, and they tend to not like change.

The other interesting element in this group is the nature of their content; it is typically more transactional and repetitive, as opposed to unstructured information. Most organizations have one or more of these types of groups. Some common examples are in finance, engineering, operations, legal, and human resources. Also, many industries are very used to structured processes and governance such as healthcare, insurance, and financial sectors.

Both types of groups, if already using shared drives as the vast majority of the content world does, believe that they have a system for organizing content and that it’s just fine. Whether a knowledge worker admits it or not, their slice of the shared drive pie is a dumping ground for content. Sometimes it’s organized, and at other times it was created while on a conference call. The net result is a system that they know because they built it, but one that does not serve the overall organization well. To understand how people might want to use your SharePoint ECM solution, it’s important to understand how content is being stored in these shared drives today.

How users currently manage their content is a good indication of how they will want to manage it in SharePoint. Habits are very hard to change, and if a person has been doing a particular job function for many years, they are used to adopting workarounds to get the job done. At the first sign of any struggle, a user may revert to old habits, such as looking for a workaround or complaining that the new system just doesn’t work. This is compounded by daily stress and workload that make the burden of using a fancy ECM solution even higher.

The four questions we asked at the beginning of this chapter were not outlined to establish any specific components of your implementation. Rather, they are meant to generate introspection so that you will begin to understand where your problem areas will be. You should use this knowledge to identify what groups will provide opposition or support for your ECM team’s planning of a successful implementation and extension of SharePoint. The next step is to use this information to address the specific areas of the Management portion of the content life cycle. The following outlines the primary areas to consider for who manages the content. Please keep in mind that the management of content is not the same thing as who manages the security or access levels to the content.

Security

Document types/retention schedule

Document audits

Managing bad habits

Policy creation and implementation

Who manages content?

As a best practice, we recommend that the individual(s) in charge of managing content in SharePoint should not be the same people who maintain SharePoint, typically the IT department. In fact, depending on how large your deployment is, you can and should have many people who are responsible for managing content. The more people who are active managers of content, who understand the principles and benefits of your IA, the better chance you have of maintaining control of your information.

SharePoint as the ECM platform is the responsibility of the IT department, from the server and storage infrastructure to the farm installation and configuration. Their involvement or, rather, responsibility should stop at the site collection level. This is typically a blurry line, where IT responsibility ends, and your IA and general ECM governance begins. Below the site collection, an individual(s) who has a vested interest in the success of ECM in your organization should manage your ECM solution.

In many organizations, this person is the Records Manager, Content Manager, or Information Architect. Some small organizations don’t have the luxury of such a position for budgetary reasons. Even some larger organizations haven’t identified the need for this specific position. There are a variety of reasons why this might be the case—for example, there is little regulatory oversight or the organization has never been party to litigation. In such cases, you have to consider appointing a team that is responsible for the content or, if the organization is large enough, individuals in each functional unit, often referred to as Super Users.

This is challenging in many organizations because both IT and the Content Manager or Super Users have, or should have, a stake in the ECM solutions performance. For example, it should be a defined part of their regular responsibilities or tied to a Managed Business Objective (MBO). In some cases, this can create challenges between IT and the Content Managers because they often do not have the technical know-how to take over at the site collection level.

Note

Managed Business Objective (MBO) is a tool used by many organizations to establish goals above and beyond personnel job description. Monetary incentives usually accompany achieved MBOs to help acknowledge the extra effort required to meet the objectives. For example, a portion of the quarterly employee bonus can be based on MBO. Including MBOs for the effective use of the ECM platform is one technique that organizations are using to encourage proper adoption without the use of technology.

The first problem is usually addressed by creating synergy between Content Mangers and the IT staff. Both should be on the ECM Committee, which we will talk about in Chapter 5, and both should be bound by the common goal to make the ECM solution work, both technically and operationally. In most organizations, this works out well, but it also always helps to draw a clear line in the sand stating that IT is responsible for everything up to site collections and the overall performance and uptime of the farm and that Content Managers are responsible for everything below site collections.

Note

Specific roles and responsibilities should be part of a well-defined governance plan and formalized documentation. Having a person(s) assigned to the role of Records/Content Manager or Information Architect is the best scenario and can help further define the organization’s commitment to ECM.

The second problem is much harder to address, and organizations can really address this issue only when they identify and recruit the required staff well, before SharePoint is selected as a platform. Many organizations luck out and can identify users in each function who aren’t in IT but are technically savvy and eager to be a part of this exciting new technology initiative. As for officially titled Records Managers and Content Managers, it is good to make sure that they have sufficient SharePoint experience and training. A rule of thumb is that it takes about one year with hands-on experience with SharePoint to really begin as an administrator.

Security

If you have ever attended a SharePoint event, you know that one of the most common topics or common subjects within a given topic or track is security. This is both good and bad. The good news is that there are many individuals out there who know a lot about SharePoint security. The bad news is that the number of sessions at any conference on a particular topic is a gauge of how complex that topic can be.

Our approach is different. When it comes to ECM security, the best principle is that less is more, so keep it simple. This is one of the many areas of building an ECM solution in SharePoint that could result in planning paralysis.

We know and can recommend that simple is better because indirectly, while you are designing a fantastic IA (covered in Chapter 2), you are determining security. That’s right: security users and groups are very similar to IA. And fortunately, IA in SharePoint indirectly helps determine your security structure. So with a well-designed IA, part of the security work is already done for you. Now let’s cover the two basic types of security in SharePoint: repository level and document.

Repository

Repository level security is the shared responsibility of the Content Manager(s) and IT. The repository level security should map to functional or departmental security groups in your organization’s active directory. Active directory most often is where users and access levels are assigned. Typically, users are added to groups based on their department or function. Most organizations have this well established, which also means it cannot be changed. Although every organization is different and therefore every active directory forest, tree, and domain structure is different, the goal is to have these high-level functional groups align with the SharePoint repositories.

As we explained in Chapter 2, repositories are both the logical and physical location of content. The top-level repository is the web application, also known as the site collection. The next level is the site, and the final level is the library. The number of web applications is roughly determined by the size of the organization and the amount of content. While it’s certainly possible to have multiple content databases, in this book we will assume that there is one content database per web application.

This means that the site collection is the first point, or envelope, that you can apply security to. For ECM, three general principles to follow for security are as follows:

Never assign user level security.

Never assign security lower than the site.

Never break inheritance lower than the site.

In general, one of the biggest challenges of security is the administration of it. Alarm bells go off in every organization when the security topic comes up; multiple people want to take ownership, and frankly, it becomes overthought.

When you think about it in simple terms, it’s rare to find an organization where everyone in a department or group can’t see all documents. Of course, there are exceptions; for example, Executive Management. However, the proposed approaches for IA that we outline in Chapter 4, will show how this is addressed by having a specific site collection or site for the organization’s leadership groups.

Therefore, the primary consideration is the groups, what the groups are applied to, and cross-functional sharing.

The ideal scenario

Based on our experience, we propose that each group gets assigned their portion of the IA. For example, the Human Resources security group gets assigned to the HR site collection or, for small organizations, to just a single site. The Engineering security group gets assigned to the Engineering site collection for large organizations or to a single site for small organizations. The manager of both of these functions should belong to a separate security group called Managers, and that group should be assigned to the Managers site collection for large organizations or to a single site for small organizations.

Our goal is that you begin to see a pattern emerging that will become very clear in Chapter 4 as you work through the practical examples. You should also be able to guide each group as they build out their portions of the IA by using the examples and templates we provide in this book.

This will also allow you to adhere to principle number 1, which is to never assign user-level security. With this method, you should never have to apply ad hoc security to individual users in the organization. The primary reason that we do not want you to do this is because managing it is very problematic, if not impossible. Without a third-party management tool, it’s impossible to know where these ad hoc users have been assigned. It is also very difficult to make sure, when security is no longer needed or when the user is no longer with the company, that the user can be or is removed.

Team site

Cross-functional projects/repositories needing many users to be involved should be created in a separate site collection for teams. In this site collection, the root-level security is the entire organization, and the team leader will solely determine the individual team site security in an ad hoc manner.

This seems like an exception to the rule, and it is. But the concept is still within the principles of ECM. The result of the project—that is, the individual team site—is the document that belongs to ECM. Therefore, the team site itself is a sort of record. The team site collection is an ECM system for all projects, and because projects have short lives, the project and all activity within that project live and die there.

The biggest challenge with this approach is to make sure that team sites are deleted when the project is over and, if the result of the project was a document, that the final document ends up in the approach function in the organization. For this, in SharePoint 2013, we recommend using the new site disposition functionality, and in SharePoint 2010, we recommend looking at third-party tools or relying on the team leaders, via policy, to clean up after themselves.

This approach addresses the need for cross-functional work, keeps the principles of ECM in their designated functions, and makes IA and ECM management flexible. Figure 3-1 shows an example of a project team site used as a cross-functional repository for the Projects team site.

The final two principles we established for repository security were never to break inheritance below the site level and never to assign groups lower than site level. Both are established because of the fact that security is very hard to manage, and as soon as management is lost, it’s a rapid downward spiral in security and sprawl issues. This is especially true with the new share functionalities present in SharePoint 2013. Therefore, to keep security very clear and administration clean, we recommend that security be applied only at the lowest repository envelope, which would be the site collection for large or document-heavy organizations and a single site for smaller organizations. After this has been enabled on these repositories, it should not be broken out any lower.

It is even possible to get item-level security, and while it sounds fun, it’s not. We have yet to find a fully justified use case for when item level security is right.

Site administration and recycling

In addition to repository security, the following SharePoint-specific security considerations will be important to understand and plan for when implementing your ECM solution:

Site collection

Site administrators

Recycle bin

Who has access to administration functions on the site and, more importantly, the site collection is an important consideration, primarily because of the risk it could impose on the stability of SharePoint. A site collection and site administrator have the ability to modify security, enable and disable features, navigate to terms sets, modify content types, and so on. Without malicious intent, it’s very easy to change something small, such as a content type, and harm the user’s ability to use the system.

The process we recommend is to have no more than three site collection and site administrators. If at all possible, assign only site collection roles, and no ad hoc site administrators. Your ECM solution, when established, should not change often, so the need for a site administrator should be minimal. The group of three should include two Super Users or Content Managers and an individual from IT–most likely the farm administrator. The purpose of three is redundancy and accountability. In the governance section of Chapter 7, we will talk about tracking these users and changes.

Note

These three individuals don’t need to be 100 percent sure of all the functionality available in site settings, but they should be aware of the risk of changing things suddenly and have an appropriate level of cautiousness when making any changes.

The recycle bin in SharePoint has special considerations at the site and site collection level. The recycle bin is where documents go when they have been deleted. By default, recycle bins are set up in two stages. This means that there are two recycle bins: the site recycle bin and the site collection recycle bin. The settings for this are found on the web applications settings page in central administration, as shown in Figure 3-2. It’s possible to turn off the second stage recycle bin, and it’s also possible to set a purge date for when the recycle bin is cleared: by default, 30 days.

This method is useful because it’s not uncommon for users to delete a document in the site and, on day 31, realize that they should not have. The consideration that needs to be made is who can restore, empty, and administer the recycle bin? Typically, the same three site collection administrators we outlined are the same who have access to administer the recycle bin. There are also two separate types of bins at each level: the end-user recycle bin and the administrators recycle bin.

Note

There are unique scenarios for some companies where even the site collection administrators should not see the content of deleted items. In this scenario, if acceptable, we recommend enforcing with policy, due to the small number of site collection administrators. Otherwise, a custom solution is required to modify the security of the recycle bin.

It is also good to plan the limit size of recycle bins and to have a policy for when, if ever, they are emptied separate from the defined purge period. Ideally, organizations will establish a time period and adhere strictly to this rule because, as we will see in Chapter 8, following your own policies is critical for remaining compliant.

Document

We have established security to the repository, so now it’s time to consider what a user can and cannot do with the documents that are stored in the repositories.

On a site and library level, you can manage different types of security groups. These groups, separate from those in Active Directory, determine what can be done on a document level. For example, you can decide which users can edit documents and which users can only read documents. These settings should not be viewed as tools for producing content; rather, this is the security that happens on the repository. They should be viewed as a way to protect the content of documents from unfortunate editing by the wrong people.

You will find many approaches and views on this. Unfortunately, most organizations mimic security levels in their active directory. This is OK, but it usually results in too many groups to manage. Then there is the approach to consider just the types of activities that can happen to a document. For example, a user could perform any one of the following activities:

Design a document Provide the ability to view, create, delete, approve, edit, and customize.

Edit a document Make modifications to existing documents and delete them.

Contribute to a document View, create, update, and delete existing and new documents.

Read a document View and download existing documents.

View only This is similar to read, but you cannot download.

Moderate a document View, add, update, and delete items.

There are a few special actions that are reserved for custom solutions and web services that we are not covering in this book. All of these options distill to the ability to create, delete, modify, read, download, approve, and customize.

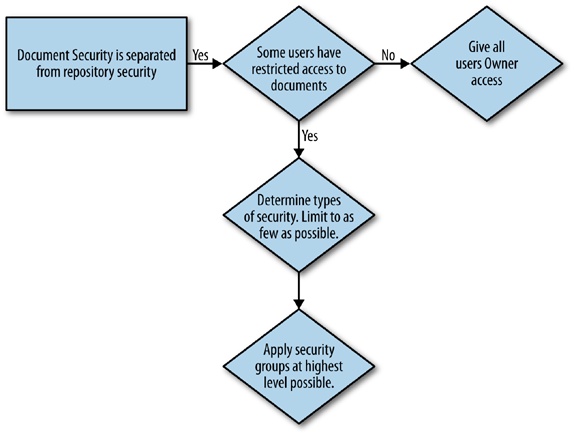

Because we have isolated document-level security as a way to protect the content of documents, we have included a decision tree in Figure 3-3 to illustrate a process of defining document-level security.

Even between experts, this approach can be quite controversial. The reason for such a radical approach is to maintain the ease of administration that SharePoint needs to have so as to ensure that the platform is adopted and extended. We believe that most organizations will have the requirement for the minimum level content security groups, which are Full Control and Read-Only.

Document management

Also at the content protection level are the check in/out functions and the versioning functions. Checking out a document is a very important yet simple tool in ECM that ensures that as a document is being edited by a user, the editing process is not impacted by another user who views the document.

If you use default settings in SharePoint, it is up to the user to check out documents and to make sure to check them back in, at which point they should also add comments. Because it’s at the user’s discretion, you will find that when they own the content, they will tend to use this feature, because all users are sensitive to the additional work that could be created if someone else saves a version while they are editing. However, it’s not guaranteed, so we recommend that you enforce that whenever a document is being edited, it is automatically checked out. As shown in Figure 3-4, you can do this on a library level in library settings and by selecting versioning settings. You can select Yes for the option Require Documents To Be Checked Out Before They Can Be Edited?

A side effect of this important feature is users forgetting to check documents back in. This should first be addressed with training, and eventually there will be enough social disruption around popular documents that users will make it a habit. Administrators do have the ability to force checked-in documents. We have even seen some unique customizations that run on a daily basis to find checked-out items and remind users to check them back in via email. This is another people and technology problem that is better to address with people first.

Note

Custom solutions add a variable to SharePoint that could impact extensibility, migration, and stability of the system. From time to time, we talk about custom solutions. By default, we recommend always using out-of-the-box features to ensure the life of your platform and that the ability to migrate to future versions is as easy as possible. When we talk about these recommendations, we are only hinting at some interesting possibilities; they should be considered carefully.

While in the versioning settings, we have something else to look at here. The next important consideration in protecting content, and a very common ECM feature is versioning. There are two types of versions, as we noted in earlier chapters. The first type is major versions, and the second is minor versions. A major version is everything to the left of the “.”, and a minor version is everything after. For example, if a document has version 3-2, it has major version of three and a minor version of 2. Both sides of the decimal can be essentially infinite. Therefore, version 3-125, the 125th minor version of major version 3 of this document, is possible but not advised.

The first consideration is whether you should use versioning. In our experience, it’s hard to find an ECM scenario where versioning is not a necessary feature. This helps make sure that the activity associated with the edits to a document is well contained and that you can revert to old versions if you need to. We did a study that shows that about 1 in every 20 documents has a need to be reverted back to a previous version. Only if documents are read-only, if you have technical limitations on your content database, or if you are advised by legal counsel (because every version is admissible content and available for eDiscovery) should you consider not using the feature.

When an organization has decided to use versioning, it must consider whether or not to implement minor versions. It’s rare for an organization to have a need for minor versions unless they have implemented publishing. Publishing is the process of taking major versions of content and publishing them to other users in the same site or to intranet/extranet sites. This allows major version of documents to be published while the creator of the document can continually modify working versions. In most cases, organizations need only major versions. Unless you have strong documented reasons for doing otherwise, we recommend sticking with major versions only.

The final item to consider for content security is draft item security. It is possible to limit which users or groups can see draft versions of documents. In ECM, we feel that any setting other than “Any User who can read items” is dangerous. Does your organization use drafts and, if so, why? We find that most organizations, unless utilizing publishing features in SharePoint, don’t need to use the draft feature in most cases. If you are utilizing drafts, because this is such a subtle feature, it’s very difficult to document whether or not there is a special security consideration. As a result, if multiple editors are collaborating on a document, with some having draft privileges and others without, the problem of lost content will not be easily identified. It might be necessary at times for people without proper edit security to know about the existence of draft content. For these reasons, we recommend that, when using drafts, you should allow everyone to see the draft versions that exist.

We have outlined all the considerations for managing document repository security, ensuring integrity of the content, and special considerations as it relates to working with content in ECM. Now that your users have captured the content, your ECM solution is managing it because of the IA the ECM team put in place, and the users are putting the content to use. In the next section, we will explore the best practices associated with productive use of content.

Delivery of content

We have covered a lot of ground so far, but none as important to the people in your organization as the delivery of useful content. Content is useful when it is delivered to you and others in a familiar and consistent manner. The beauty of consistency is getting what you expect, whether it’s your favorite restaurant, a solid relationship, or relevant content. When you don’t get the experience you expect, especially if it is foreign to your common practices, whether it be in daily life or in business, you’re going to shy away from that experience.

In this section, we will build on the Capture and Manage aspects of ECM by emphasizing a strong method for delivering content to your users. You want this to be a fast and effective experience for them, getting them the content they are looking for in a consistent manner. This is very important for user adoption, which is the ultimate factor in achieving success for your SharePoint ECM solution. Searching, finding, and consuming content is where organizations get beyond all the parts of ECM meant solely for the input and management of content and into actually using it for daily activities. It is where the mass of unstructured content will begin to meet all the back office line-of-business systems and processes used in daily operations. We recommend that you adhere to the following three elements:

Consistency

The benefits of being consistent in your SharePoint deployment have been made clear throughout the book regarding consistency in how sites and IA are set up per department and consistency of content types and libraries. The same is true when you think about the ways you will put content in the hands of users for editing and consuming. The benefits to remaining consistent will be measured in the ease of maintenance, decreased help desk support, happy users, and the ability to expand the ECM solution in repeatable ways that can truly benefit the organization. This will happen by planning for and incorporating consistent file formats based on need, consistent views and viewing, search functions, and web app updates.

Consistency of updates means that when you change the system you change it in repeatable and expected ways. End users fear change; this is a truth that will not go away. You should avoid changing the system frequently or in ways that alter the familiarity or steps required to interact with your SharePoint ECM solution. When you make changes, they should be regular periodic small updates, and any large changes should involve a prior notification. A fair amount of selling the change should be done with the users long before the change is made. Most updates to a farm that are visible to the user relate to consumption of content, which is why change is considered as a topic here.

To interact with content, users have to access it first. Access to content happens in two ways: by browsing or by search. Unfortunately, we find that the current trend is “throw it in the bucket and search for it.” In a traditional line-of-business operation, this is not extremely effective. It is ineffective because search is the most subjective way of accessing content. In search, the burden is on the user to know the proper terms and format of a search query to get the document they seek. We would like to pose this question for you: If a user knows this much about the document, should they need to search? It’s rare to find documents with enough content, or content in the right place, for search to be a highly effective method of accessing content. A single search is usually a 50/50 event, but after multiple searches, the user gets the feel of results and can dial in the results they are looking for much faster.

Therefore, we encourage organizations to consider search as the alternative when browsing does not work, rather than as the initial approach. In content browsing, a user drills down into the document they know they need, and because you have designed a good IA, they will get there very quickly. Indirectly, the more users need to search, the greater indication of poor IA planning.

Browsing and navigation

Browsing for content starts at the web application level. Users have to first identify where the document repository content lives and then the logical location of that content. Fortunately, we have explained why good IA is going to help you make sure that users spend most of their time in a single web application, making the need for extended navigation irrelevant.

The three main ways to navigate content are as follows:

Top link bar

Quick launch

Tree view

The first two are very common, and the last more common than it should be, because it implies problems with IA.

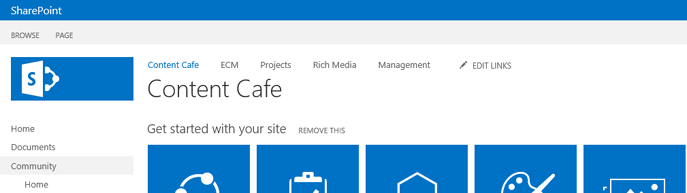

The top link bar, as shown in Figure 3-5, is the navigation at the top of the site. This navigation is generally reserved for physical repositories or subsites. It can be customized to link to any location via URL, but we recommend isolating to other web applications on the farm and subsites within the current site collection. You might also consider linking here to common resources that every employee in the organization can benefit from. As stated earlier, the key here is consistency. This is true for all navigation. Be consistent in how you name and order headings in navigation. Also be consistent about what the headings are. Navigation methods that are regularly changing will result in users finding another way to browse for content.

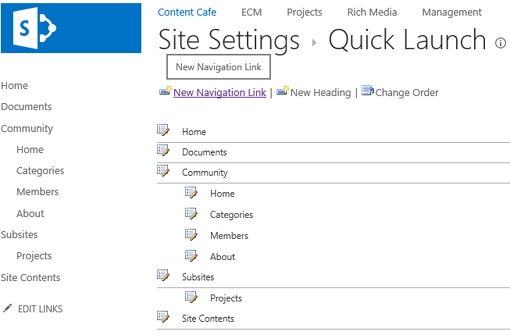

The quick launch pane is on the left side of the browser. It is typically used to show all lists and libraries. Our recommendation is that quick launch be used only for listing libraries and lists in ECM sites, with the exception of cross-functional site links such as extranet/intranet quick access—that is, locations that you know a user will frequent. You can do this by creating a new navigation link, as shown in Figure 3-6. Navigation links can link to locations in the farm or locations outside the farm that are accessible and referenced by a URL.

All the links in the quick launch are grouped by headings. Usually, headings are limited to Home, Libraries, Lists, Tasks, and Calendar items. In ECM, we generally do not see the Task or Calendar item in sites; these are reserved for the team sites discussed previously in the context of the Manage section, so these headings are often removed in favor of just Libraries and Lists. Because headings are also linkable, it’s possible to have the headings themselves be the logical storage—for example, the “docs” library instead of “docs” being under “libraries.” The benefit of this is streamlined navigation, but it becomes troublesome if you mix varied types such as lists and libraries. The primary recommendation, as stated earlier, is be consistent and keep your navigation simple. As a best-practices approach to simplicity, we recommend that your SharePoint ECM solution include only headings that link to libraries such as “Documents,” “Rich Media,” and “Email.”

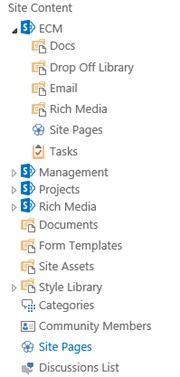

Tree view is an additional feature that can be enabled on SharePoint 2013 and is a way to visualize the relationship between logical and physical storage to its parent logical and physical storage. Essentially, when you turn tree view on, you get a new web part, as shown in Figure 3-7.

Another huge aspect of content view is library views, another tool that is either used not enough or in excess.

Many organizations are not aware of the extent that views in SharePoint can be modified. You can change columns by removing and adding which are visible. You can group content based on metadata, and you can create views that essentially filter content. Organizations that tend to use this in excess will have upwards of 10 views for any one library. This is an indication of bad IA. Organizations that are using the out-of-the-box views are using the tool too little and not leveraging the power of sorting by columns and filtering. These organizations will tend to be the same ones that use folders to organize their content.

There is no magic bullet on views, but there are a few guidelines. Every column shown should provide value to the user in the following ways:

If a column is useful only for some automation process or special type of user, it should be hidden or a part of a special view just for those types of users.

Columns should never exceed the right side of the page on a typical browser. Columns that are not visible in a single window are not usable.

Grouping is very powerful, but use this feature with caution and provide adequate user training as to the purpose of grouping. Grouping is used to aid a user who is browsing for content, while lists are used for more robust processes.

Limit the types of users who can create views, and make views consistent in all similar libraries across the entire SharePoint farm.

Site contents

Next on the navigation list is the viewing of site contents. In SharePoint 2010, this is called “View All content,” and in SharePoint 2013, it’s called “Site Contents.” Asking one to “Click View Contents” is a common phrase, but we feel a crutch. It should not be required for the typical ECM user to navigate to lists/libraries or contents that are not otherwise accessible via the quick launch. Typically, if this is being used, it’s a training problem, usually the result of someone far more experienced with SharePoint teaching how they use SharePoint, instead of how an end user should be finding and viewing content. Unfortunately, it is very common for a SharePoint site to have so many places to navigate from that an entire separate window to show all the contents is required. Both situations are not sustainable for widespread user adoption or simple browsing. We recommend keeping this tool a little secret, to be used by your super users only.

When IA fails or bad content somehow gets added to the system, the only option for accessing that content is search. Full-text search enables an index to be created from content stored in the body of a document. The goal is to get the user to the content with as few clicks as possible. With good consistency of content across the farm stored in a well-designed IA, a user is more familiar with content, and users can find that content based on keywords, where it’s located in the farm, and other metadata searching.

Search

We have all experienced light and overloaded search results or getting too few results or too many. To eliminate the problem of having too few results, you want to make sure that indexing across the farm is adequate and that all the content in the farm has the appropriate iFilter activated so that it can be indexed. We can eliminate the problem of having too many results by filtering results using Boolean logic search terms, if/and/else/equal to, or search refiners.

Note

Now search in SharePoint has evolved to include Boolean logic. For example, I can make a query for documents where the title starts with SharePoint but has the word ECM in the body. It would look something like this: (“title:SharePoint*” AND “ECM”).

Because Boolean searching is not a common tool, something more is needed. Users are often in too much of a hurry or not advanced enough to use Boolean logic. One way you can help them get to their results faster is by using search refiners.

Search refiners are generated automatically based on a document’s structured metadata. When you do a search for documents that start with “SharePoint” and contain the word “ECM” and you get too many results, you can refine your results by knowing simple things about the document, such as the author or when it was created.

Refiners can be taken even further, by including keywords and tags. Specific terms from the body of the document can also be generated on the left portion of a search panel, as well as their hierarchy. There is some customization required to get this feature to work, but it is one that is well worth the effort.

Note

Remember that structured metadata is metadata that is generated by the system, such as author and modified date.

Farm administrators can do even more to assist the user in finding content. They can do things like visual best bets. This is where a particular document is highlighted at the top of a search based on a keyword. The relationship between the keyword and the best bet has to be established manually. This helps users know what is the most important document for that search term.

The trick with the best bets option is keeping it current and relevant. This usually requires an administrator specializing exclusively in search and who has the relevant operational domain knowledge or knows how to obtain that knowledge within the organization.

Another common feature is linking content to individuals by including people search in the search results. By default, this appears on the right side of the search results and is effective only if you have active MySite pages for your users.

Viewing

After a user has browsed to or searched for a document, they need to have access to view and edit the content.

In SharePoint, there are two options for viewing content: either via the client application or via the browser. Surprisingly, the answer as to which to use is highly dependent on the licenses your organization owns and the makeup of your users’ desktops. For example, if your users have Microsoft Office installed on their PCs, viewing via client application might be very convenient. If you have users accessing content on mobile devices, you need to spend time on a great browser viewing experience.

It also depends on your SharePoint licenses. To get the most robust experience with in-browser viewing and editing, the organization should invest in licenses to the Microsoft Web App server. This is a separate SKU and server on the farm that manages the real-time editing of documents in a browser. This tool allows both mobile users and PC users to have 80 percent of what is available in any client application for office documents.

To help ease your decisions, we recommend being consistent. Supporting various types of clients can be difficult. For example, if your organization is dominated by local network PCs with Microsoft Office installed, it’s recommended to make the “open in client” application the default use case. Additionally, this will help if you have other file formats that are not a part of the Microsoft Suite.

If you can purchase licenses to add Microsoft Web Apps Server, we recommend that you standardize on editing and viewing in the browser, to the extent where you remove Microsoft Office from the users’ desktops or laptop PCs. For unique circumstances for some users, you might allow the client integration with the local version of Office.

Note

Separate the readers from the creators. In many organizations, those who create the content and those who read the content are not the same. It is possible to consider different modes of operation for each. For example, readers should be able to work with all in-browser viewing of content, while creators might need Office client applications.

Finally, there are third-party viewing tools available that cross a spectrum of file formats. When your users are doing a lot of read-only access to documents, these tools might be useful.

Preservation

Preservation of content is an aspect of delivery, because typically preservation is a process of document conversion and movement to another location.

Preservation focuses on content that has historical importance to your organization. The types of content can be diverse and vary depending on the type of organization, enterprise governance, and any regulatory considerations you might have to contend with. The breadth and depth of preservation is very noticeable in the government arena, where many documents have historical importance and, in some cases, need to be kept forever.

For example, the documents associated with city planning could have a life cycle that requires them to be kept forever, to retain the historical significance of when, where, and how land use decisions were made. It’s key to understand where SharePoint ECM begins and should end in terms of active content and archiving.

In the case of historical documents, the importance of managing a content life cycle does not generally have an impact for a SharePoint ECM solution, because many of the historical documents should be stored either on permanent media or on microform.

Note

We recommend that you focus your SharePoint ECM solution on active content. This is content that is being created, reviewed, and shared and that has value to the organization at large for completing a job function or transaction. We do not recommend that you use SharePoint as an archive or long-term preservation solution.

Even if preserved content is still a part of SharePoint, it’s recommended it be moved to a completely different SharePoint farm or, at minimum, to a site collection. The reason for this is that SharePoint is built for high activity and interaction from users, whereas preservation is about content that is interacted with very rarely or only for research purposes.

If you are keeping this content in the active SharePoint environment, there is a large opportunity cost that is taking valuable resources away from other high-value content. It is taking up space from your primary storage that should be dedicated to active content. Also, it could be impacting the performance of the farm, but most importantly, it’s accessible by users who might or might not know the difference between preserved content and active content.

We recommend the following steps when determining how content moves from the active portion of its life cycle to the preservation stage:

Determine where the preserved content will live. It is assumed that as a part of the process of preservation the content will move. If you are saying to yourself that preserved content will simply be placed in a separate library in the same location as active content, this alone is not considered preservation.

Determine the long-term preservable format that the content requires.

Determine the automated or manual process that will move and convert the content.

Determine a custodian for preserved content. This will be an individual or external organization.

Determine the format of metadata for preserved content, and include in that metadata the last location where the content was saved in SharePoint. This is important to establish the chain of custody.

If you choose SharePoint as the final location for preserved content, consider methods of remote blob storage (RBS) for the preserved content. RBS is a database configuration that allows certain content to live outside of the SharePoint database while maintaining its accessibility through SharePoint. This allows you to keep the content in the SharePoint user interface without the load on the database. Using RBS is not recommended for active content but only for site collections where you have moved or are referencing preserved content.

It is a great practice for organizations to start either preserving or offloading inactive content, or disposing of it according to a predetermined retention schedule. This ensures the efficiency of the system and prevents users from being overloaded with content that is no longer relevant. This should be done in accordance with the following activities performed by an experienced Records Manager:

Create a records inventory to determine the breadth and depth of all your organizations records, both physical and electronic.

Create a retention schedule that clearly outlines the definitions of content, based on several parameters that are relevant to your organization. At a minimum, this usually includes document type, records series, retention period, active date, and inactive date.

Legal Holds can also be established for items identified during litigation discovery processes. These are known as Interrogatories and Requests for Production (ROGs). In this case, content objects can be placed on hold with a timer. If they are touched or further requests are made before expiration of the timer, it can be reset accordingly.

Create a records retention policy that clearly outlines the procedures and governance of records for your organization. This usually includes the review and blessing of your legal department and executive branch.

After these activities have been performed, you can use the information in the retention schedule to configure SharePoint to support the preservation of content at the appropriate stage of its life cycle.

You have now completed the reading necessary to understand all the series of stages that content traverses during its life cycle. We began with defining Enterprise Content Management in our introduction. We then walked you through each of the major steps required for a SharePoint ECM solution. To recap, we have covered the following areas:

Getting content in, or Capture Upload, MS Office, scanning, native documents, forms, and streams

Configuring site(s) collections and document libraries, or Store IA, versioning, formats, and transformation

Moving content from person to person, or Process Business process management, workflow, business intelligence, and eDiscovery

Finding and collaborating on content, or Manage & Deliver Navigation, editing, viewing, searching, and preserving

Next steps

We will now outline two different strategies for using your newly acquired ECM knowledge. First we will look at a small or departmental deployment of SharePoint ECM, and then we will make the necessary adjustments for a much larger scale project. We will be providing step-by-step instructions and giving you some nice outlines that you can use for documenting your IA.