Retention and file plans

In this chapter, we introduce the topics of retention schedules and file plans. We also introduce key records management terminology and map these terms to Enterprise Records concepts.

This chapter is organized into sections that cover the following topics:

•Retention schedule

•Retention schedule planning and creation

•File plan

•File plan planning and creation

•File plan in IBM Enterprise Records

•File plan case study

|

Disclaimer: We provide the information in this chapter as is without warranty of any kind, expressed or implied. IBM is not responsible for any damages that might arise out of the use of, or otherwise related to, this information. Nothing included in this book is intended to, nor shall have the effect of, creating any warranties or representations from IBM (or its suppliers or licensors), or altering the terms and conditions of applicable agreements governing the use of IBM hardware, software, or services.

|

3.1 Retention schedule

A retention schedule is a timetable that specifies the length of time that a record must be retained before destruction. A retention schedule describes a company’s regulated records, their ownership, regulatory citations, and the retention period based on legal, regulatory, and business needs. The company needs to review the retention schedule from time to time and to dispose of records in accordance with the retention schedule.

Most companies have some form of retention schedule or retention rules for their records. If your company has a retention schedule, it should be reviewed and revised according to requirements that we describe here. If you do not have a schedule yet, you must create one.

A retention schedule can be guided by the following requirements:

•Compliance and regulatory requirements. Industry and government regulations often impose different retention requirements for records.

|

Terminology: Compliance is the act of adhering to and demonstrating adherence to internal or external regulations. A regulation is a compromise between prohibition and no control at all.

|

•Fiscal requirements related to recordkeeping.

•Business requirements, which can include audit, company’s retention policy, legal counsel opinion, or business continuity reasons.

•Administrative need for the record.

•Historical need for the record.

To determine the retention period of a record, stakeholders from legal counsel, compliance officers, and business users need to be involved because the requirements vary from different countries, states, municipalities, industries, compliance and legal jurisdictions, and document types. The retention schedule is updated continually as business and regulatory needs evolve.

|

Important: Companies are responsible for ensuring their own compliance with relevant laws and regulations. It is the company’s responsibility to obtain advice from competent legal counsel as to the identification and interpretation of any relevant laws that can affect the company’s business and any actions that the company might need to take to comply with such laws.

IBM does not provide legal, accounting, or audit advice or represent or warrant that its services or products will ensure that a client is in compliance with any law.

|

There are usually multiple retention rules associated with a retention schedule. Each retention rule specifies how long records are retained and what to do after the retention period expires. Each rule applies to a specific group of records.

3.2 Retention schedule planning and creation

Creating a retention schedule for a company is one of the most critical tasks in records management. To plan and create a retention schedule for a company, you can use the following guidelines to create a retention schedule, as shown in Figure 3-1 on page 68:

3. Conduct a records inventory.

4. Understand record series.

6. Compile retention schedules.

7. Implement file plans.

Figure 3-1 Planning a retention schedule

3.2.1 Develop a records management policy

A records management policy is based on legal, regulatory, and business requirements. If the company does not have a records management policy, a preferable practice is to develop one. A policy is a living document and should be reviewed and revised as business need evolves. In addition, everyone in the company must adhere to the policy. Records management procedures are developed in accordance with the policy. The company can use technology to enforce records management policies by attaching records management policies to the documents that reside in the repositories.

As shown in Figure 3-2 on page 69, company policy is the cornerstone of a records management program. It has a direct impact on the processes and procedures for the program.

Figure 3-2 Policy is the cornerstone of ILG governance

Example 3-1 shows part of a records management policy.

Example 3-1 Records management policy example

Essential information is information deemed necessary for satisfying corporate legal requirements for conducting business operations.

Essential information is to be retained long enough and in appropriate media to meet the laws of the countries in which this corporation conducts its operations; retrievable in a usable form throughout the retention period and disposed when the retention period expires, unless subject to a hold order.

Often, a company’s records retention policy is affected by global retention requirements. In both the United States and Canada, electronic records are usually acceptable when records are legally required to be kept.

For example, accounting records are required to be kept for six years in accordance with Securities and Exchange (SEC) Act Rules 17a-3 (17cfr240.17a-3(a)(2)) in US.

The record management requirements of Asian Pacific countries seem to parallel many of the general principles used in other regions. For most Asian countries and countries throughout the world, if a company is registered in that country, it is normally obligated to maintain accounting records for 10 years.

As explained previously, most US-based multinational companies retain many accounting and general business records for retention periods ranging from five to seven years. However, as indicated above, many global retention requirements applicable to these records specify 10-year retention periods.

One way to implement the records retention policy is to retain the accounting record for the retention period for most accounting records unless law and practice necessitate a longer period.

3.2.2 Specify records management procedures

Records management procedures are developed in accordance with the records management policy. These procedures provide the operational task, role, and outcome that are required to ensure that the company adheres to the policy and associated retention schedule.

If a company does not have a set of procedures for records management, it is a best practice to develop one. Procedures are specific to the company’s industry, the nature of the business, and the operation of each area within the company.

Example 3-2 shows part of a records retrieval procedure.

Example 3-2 Records retrieval procedure example

All retrievals must be returned in 60 days or less. If needed for a longer period, the Records Administrator is to be notified. If permanent removal is requested, management documentation to confirm retention will be required. See Process Contacts.

•Access the Records Retrieval Form at web address: ...

•Complete all of the required fields.

– Enter the box number you are requesting. If a file is being requested, complete the "File Number" field under this section as well.

– Be sure to review the Priority selection as it will default to "Normal" Service. If urgent, same-day delivery is required, select the emergency option.

•When the form is completed, follow these instructions:

a. Save the document as a Word file.

b. After the file is saved, prepare an email to Administration Team with the supply form included as an attachment.

•Administration team will review the contents of the form.

•You will receive a response in 48 hours (through email) to advise that your order has been processed. Administration team will provide an order number and expected day/time for delivery.

3.2.3 Record and update regulatory requirements

Many countries around the world have laws about recordkeeping. Most are applicable to physical and electronic records, some specify the active and inactive retention period, and some have special compliance requirements for storage.

Regulatory requirements vary from country to country, industry to industry, legal entities, states, and document types. See 1.5.1, “Addressing regulatory requirements” on page 10, for an overview of regulatory requirements that are pertinent to a financial institution in the US.

3.2.4 Conduct a records inventory

Companies must conduct an inventory of their documents. A document inventory is a list of documents that exist within a company. The inventory also describes the characteristics of records that are created or captured. The inventory can be at departmental level and can be conducted through questionnaires.

Table 3-1 on page 72 shows an example of a records inventory template.

|

Note: The list that we show here is not meant to be exhaustive.

|

Table 3-1 Sample record inventory template

|

Record Code:

|

Record Description:

|

Record Owner:

|

|

Format:

|

Location:

|

Department:

|

|

Retention Period:

|

Disposition:

|

System Name:

|

|

Storage Media:

|

|

|

After obtaining a document inventory, you can categorize the documents into appropriate categories. Users should include all types of documents, including paper records, microfiche, electronic documents, email, fax, instant messaging, collaboration content, voice recording, wireless communication content, audio, video, shared drive content, and Web content.

Review the existing records filing process

Many companies already have some form of records filing processes. Review and study the existing record filing process. The goal of this review is to accomplish the following tasks:

•Identify records that are being generated within the company

•Understand the hierarchical order between groups of records

•Ensure that all records from the company are presented and collected

•Identify who created the records and how they were created

This review gives a better understanding of what records the company has and helps to create the retention schedule and the file plan later.

3.2.5 Define records series

Use a single consistent taxonomy, globally, across records, business, and information technology.

|

Terminology: A record series is a group of related records grouped as a unit and evaluated as a unit for retention and disposition purposes.

|

Figure 3-3 on page 73 shows an example of a group of accounting records, which can include payroll records, accounts payable, accounts receivable, general ledger, tax records, and so on. All of these are similar in nature and have similar retention requirements.

Figure 3-3 Extract of a sample records series

By doing this, you can catalog the classes and types of information within the organization and specify where and how it should be managed. You can easily enable country and local schedule variations as needed and compare retention practices for the same information across the business and systems.

In the next section, we show how to overlay a regulation matrix over records series.

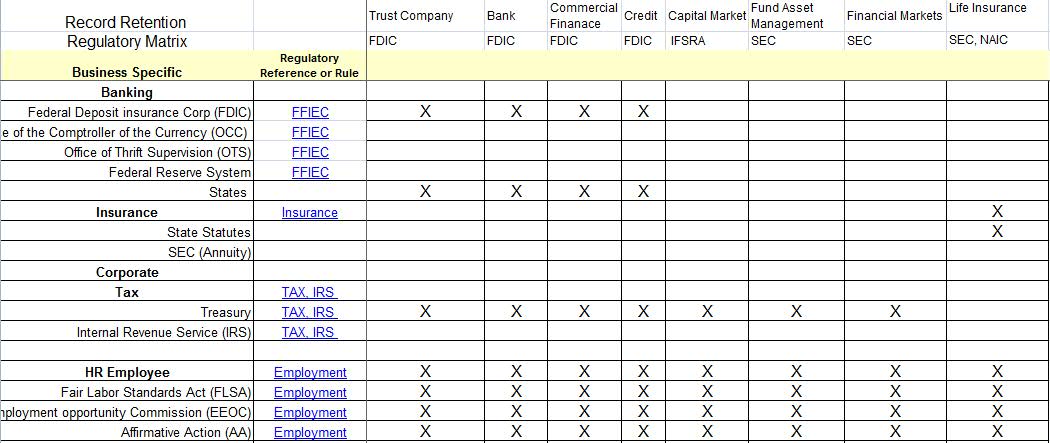

3.2.6 Create a regulatory matrix

Catalog the laws and regulations that stipulate both retention and privacy requirements, along with policies for security.

Apply laws to information to enable precise retention and privacy actions. Associate specific laws and regulations with specific classes and jurisdictions to retain less data more defensibly.

|

Terminology: A regulatory matrix provides a comprehensive list of federal laws and regulations that govern the various entities of the company.

|

Figure 3-4 on page 74 is an extract of a sample of regulatory matrix for a typical financial institution.

Figure 3-4 Regulatory matrix

Global presence

Multinational companies have business operations, offices, and records throughout the world. As companies become global, Records Managers must know which country’s laws and regulations will affect their record management policies.

In our example, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) in the US requires companies to retain accounting records for six years. However, some other parts of the world, such as China and Japan, require accounting records and tax documents to be retained for 10 years.

Data residency concerns

As more companies take advantage of cloud storage, it’s important to also look into data residency and sovereignty requirements. Some countries’ regulations require companies that deal with personal information to restrict the transfer of personal information outside of their borders. This might require further consideration when implementing a records management system and the physical location of the data stores.

In the next section, we show how to put everything together and create a retention schedule.

3.2.7 Creating the retention schedule

After gathering a complete records inventory, categorize records into groups of related records that can be filed as a unit for retention purpose. Retention period for each group should be based on legal mandates, regulatory requirements, business requirements, and good business practices.

For example, SEC 17a-4 requires that some records retained by brokers and dealers must be preserved for at least six years, the first two years in an easily accessible place. Other records must be retained for at least three years, the first two years in an easily accessible place. Based on regulation requirements and other business requirements, you can categorize that special group of records into one unit. Make sure that the records are logically grouped together (from company’s business operation perspective) and they all have the same retention period based on requirements.

In addition to determining the proper retention period for records, you must determine the disposal method for records when their retention period expires. This is important because proper disposition of records protects companies from future liability and controls information storage size. Records disposition options include (but are not limited to) destroying the records and archiving records to another records holding authority. You can also set up the system to review records when their retention periods expire and then decide what to do.

|

Note: By design, a records management system does not destroy records automatically when records reach the end of their retention periods, even when the disposition is set to destroy. The system always requires human verification before anything is done to the expired records.

|

Provide precise, actionable instructions to information holders about the applicable privacy and security obligations. Enforce them on unstructured and structured data automatically.

Also consider the following related requirements:

•Retention period

•Disposal method requirements

•Storage media requirements

•Security requirements

•Use limits

•Transport or transfer requirements

•Disclosure of failure requirements

|

Important: Retention period and records disposition method are two of the key elements in a retention schedule. Understanding your company’s records policy and records procedures and understanding and correct interpretation of laws and regulations are crucial in determining the length of time that a particular group of records must be kept and what to do with them afterward. Legal counsel and special records professionals should be involved in developing the actual retention schedule for a company.

For more information about records disposition, see Chapter 6, “Records disposition and basic schedules” on page 151.

|

Table 3-2 is an excerpt from the retention schedule that we develop later, in Chapter 14, “File plan case study” on page 295.

Table 3-2 Excerpt from a retention schedule

|

Category

|

Description

|

Citation

|

Total retention period

|

Disposition

|

|

Corporate governance

|

Books and records that substantiate the existence, operation and obligations of each legal entity, such as: Articles of Incorporation; Board of Directors, Shareholders

|

NASD3510 life

NASD3010(b)(3) life

17cfr270.31a-2(a)(1) permanent

17cfr270.38a-1(d)(1) life +5 years

17cfr275.204-2(e)2 5 years

17cfr240.17a-4(d) permanent

|

Permanent

|

Not applicable

|

|

Broker-dealer transactions

|

Securities records; blotters; ledgers; trade confirmations; instructions; client statements, reconciliations; trade sheets, stock bond records

|

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(1), 6 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(2), 6 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(3), 6 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4)(i), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4)(ii), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4)(iii), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4)(iv), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4)(v), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4)(vi), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4)(vii), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(5), 6 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(6)(i), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(6)(ii), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(7), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(8), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(9), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(9)(iii), 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(10), 3 years

17cfr1.31(a) 5 years

17cfr1.31(d) 5 years

|

6 years

|

Destroy

|

|

Client communications

|

Correspondence, communications (email, voice recordings and postal mail), complaints from clients, both institutional and retail

|

17cfr275.204-2(e)(3) 5 years

|

5 years

|

Destroy

|

|

Employee data

|

Monitoring and reporting on all employee-related activity and activity of associated persons, such as employee files, fingerprinting, compensation or salary, benefits, registration, licensing

|

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(12)(i), employment +3 years, 17cfr240.17a-3(a)(19)(i), 3 years

|

Termina-

tion date + 3 years

|

Destroy

|

|

Accounting

|

Financial statements, journal entries, general ledgers, P&L statements, documentation of fixed assets, employee payroll accounting records, payroll registers, tax returns, and working papers

|

17cfr270.31a-(b)(1) 2 years

17cfr270.31a-(b)(2) 2 years

17cfr275.204-2(e)(1) 5 years

17cfr275.204-2(e)(3) 5 years

17cfr1.31(a) 5 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(2) 6 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(3) 6 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(4) 3 years

17cfr240.17a-3(a)(11)

NAIC 910-1 section 4,

current +3 years |

6 years

|

Destroy

|

Here is a list of suggested fields in a retention schedule (the list is not meant to be exhaustive):

Record series A group of related records that can be filed as a unit for retention purposes. It can be further broken down into primary, secondary, and tertiary record series, if required.

Series title The name by which the group of records are known by the users.

Description Defines the scope of the records included in the category.

Office of record Refers to the owner, which can be a department responsible for maintaining the official records for the retention period.

Vital record An identifier to indicate whether the record is needed if there is a disaster. Vital records are usually stored offsite and replicated for disaster recovery purposes.

Active retention period The retention period for records that are required for current use.

Inactive retention period The period of time during which inactive records must be maintained by the company.

|

Terminology: Active records are consulted routinely in the daily performance of work. Inactive records are rarely used, but they must be retained for occasional reference or to meet audit or legal obligations. An inactive record is a concept used mainly with physical records. Inactive indicates that the record is eligible to be moved to a storage warehouse.

Distinguishing between active and inactive records is less relevant when dealing with the management of electronic records.

|

Total retention period The sum of active retention period and inactive retention period.

Citation The statutory authority or law that governs the retention of the records. For example, SEC 17cfr275.204-2(e)(3) requires that client communications to be retained for five years.

Disposition The final action for a records series. Examples of valid actions are destroy (physically destroying the records) and accession (or archiving, transferring records to other records holding authorities).

Medium The object or device where the record resides. Examples of media are paper record, microfilm, computer disk, and CD-ROM.

Records series code Can be used to refer to a citation schedule or a disposition schedule.

3.3 File plan

A file plan is an IBM Enterprise Records instance to implement tghe enterprise’s retention schedule. It is a structured, subject-based filing schema that a records management system uses to support a retention schedule. There is no universal file plan for all companies. Each file plan is unique and depends upon the types of businesses with which the company deals.

A file plan specifies how records are organized hierarchically in a records management environment. It is different from a taxonomy, which is intended to aid users for content search and retrieval. The purpose of a file plan is for Record Administrators to manage retention and disposition of records. It is used to enforce records managements policies.

|

Terminology: A taxonomy is a hierarchical classification scheme to aid users in searching or retrieving content. For example, classifying music by genre can generate this list: classical, jazz, and rock. A single area, such as classical, can be further classified as concertos, sonatas, symphonies, and so on. If a user who is searching for a piece of music knows that it is a concerto, the user can narrow the search to this category. If the user does not know that the piece is classical, the user must broaden the search.

|

In a typical company environment, there are different documents that can be associated with different buckets (or subject folders). Each folder is then tied to the retention rule, which indicates how long documents within the folders are to be kept until destruction.

You can apply retention rules at either the folders or records level, as shown in Figure 3-5 on page 81. A single record can include multiple documents or multiple pieces of information.

Figure 3-5 Classify a document according to a bucket (subject folder) that is tied to a retention rule

|

Terminology: Classification, or cataloging, is the act of identifying the correct file plan node or category into which a record needs to be declared. Classification places a record in context.

The term classification is not to be confused with the act of providing a security classification for a record, for instance, Top Secret and Confidential, as mandated in the US Department of Defense (DoD) 5015.2 Classified standard. To mark a record as classified or to declare a classified record refers to providing a security classification marking for a record. In such cases, a record has both a file plan classification and a security classification that is independent from its file plan classification.

|

3.4 File plan planning and creation

As mentioned in 3.2.4, “Conduct a records inventory” on page 71, many companies have some form of records filing processes. Before you design your file plan, review the records filing processes and records inventory that you generated when following that section. Design a file plan that models the records and their hierarchical relationships within the company.

Figure 3-6 shows an excerpt from an example of a structure for a fictitious global financial institution. The company has representations in multiple geographical locations that are then divided into different legal entities.

Figure 3-6 Partial file plan

A hierarchical file plan has containers (subcontainers and records) that comprise the file plan that represents categories of information. The highest level of folders is known as root. Subfolders are used to aggregate records based on business subjects. These categories are divided into narrower categories until a category is granular enough that it pertains to a relatively small subset of the spectrum of categories that an organization deals with on a daily basis. This level of granularity is where a specific retention rule can apply to this set of records, which we describe in 3.1, “Retention schedule” on page 66.

Users (Records Administrators) identify records as belonging to one or more of these narrowly defined categories. This granularity enables efficient location of records based on the categories of information to which they belong.

While designing a file plan, distinguish between electronic records and paper records, identify the location of these records and how and where they are created, and note any changes or migration of these records.

For information about how to create a file plan, see Chapter 14, “File plan case study” on page 295.

For information about how to apply retention rule to that file plan, see Chapter 14, “File plan case study” on page 295.

3.5 File plan in IBM Enterprise Records

To model an organization’s file plan in Enterprise Records, it is important to understand the elements or objects that the software uses to build a file plan and how they interact with each other.

There are different ways of setting up file plans in Enterprise Records. The retention policy of records can be implemented in the Policy Management module (for example, IBM Global Retention Policy and Schedule Management). Master schedule and local schedules are based on certain criteria, for example, geographical locations can be syndicated to Enterprise Records.

Another way of implementing file plan is to enter it directly into Enterprise Records.

3.5.1 File plan elements

File plan elements in Enterprise Records include record categories, records folders, volumes, and records. Categories, folders, and volumes serve as containers for records.

Record categories

A record category is a container that classifies a set of related records within a file plan. Record categories are used as the primary organizing elements to construct the tree of the file plan. You typically use record categories to classify records based on functional categories. A record category can contain subcategories or records folders, but not both. In the Base and DoD data models, you can declare records directly into categories.

A record category has a name and an ID. Both the name and the ID must be unique within the parent container.

Typically, in a function-based file plan, the functions, activities, and transactions are modeled as record categories. In the example file plan that we use in the case study, all the nodes (such as employee data, corporate governance, banking, accounting, broker-dealer transactions) are modeled as record categories.

Records folders

A records folder is a container that is used to manage and organize a group of related records that are typically disposed of together or that might need to be retained and placed on hold together as a group. For example, if you have records related to an insurance claim, it might be helpful to group all records related to the same insurance claim in the same folder. In this case, you might have thousands of records folders in the same category, one folder for each insurance claim.

A record folder has a name and an ID. Both the name and the ID must be unique within the parent container.

You can create electronic, physical, box, and hybrid records folders under a record category to manage electronic and physical records:

Electronic folder An electronic folder is used for storing electronic records and contains one or more volumes.

Physical folder A physical folder stores physical records and contains one or more volumes. A physical folder is a virtual entry for a paper folder. Based on your organization’s physical storage structure, you can model the hierarchy of physical folders in Enterprise Records.

Box A box is a container for physical records and provides a mechanism to model physical entities that contain other physical items. It is analogous to a cardboard box in which physical records are actually stored. A box can contain only physical records. It can also contain physical folders and other box folders. A box does not use volumes. Quite often, an organization needs to merely manage boxes, without explicitly keeping track of the individual records or files within a box. In these cases, it is sufficient to have a description of the box contents, but Enterprise Records does not have any elements that represent the individual items in the box.

Hybrid folder A hybrid folder can contain both electronic and physical records and contains one or more volumes. There are no functional differences between an electronic folder and a hybrid folder. However, a hybrid folder has additional metadata that describes a physical entity, including its home location.

|

Note: Avoid mixing electronic and physical records in the same container. Typically, physical and electronic records have different processes associated with their disposition. By keeping them in different containers, you can use separate disposition workflows to meet their individual disposition requirements.

|

Volumes

A volume serves as a logical subdivision of a record folder into smaller and more easily managed units. A record folder (with the exception of a box) always contains at least one volume, which is automatically created by the system when a record folder is created. Thereafter, you can create additional volumes within a record folder. However, at any given time, only one volume within each folder remains open, by default, although a closed volume can manually be opened if needed.

By default, the most recently created volume is open. The currently open volume is closed automatically when you add a new volume. If an automated approach is required for volume management based on a specified criteria being fulfilled, for example, a volume containing records of a specific calendar year gets closed automatically at the end of that calendar year, then custom programming is required as shown in Figure 3-7 on page 86.

Figure 3-7 Records category, folder, and volume

A volume is the same type as its parent record folder (electronic, physical, or hybrid) and can contain the same type of records as its parent. However, a volume cannot contain a subfolder or another volume. A volume always inherits the disposition schedule of the record folder under which it is created. You cannot define a disposition schedule that is independent of the parent record folder.

|

Note: The concept of using a volume to subdivide the contents of a record folder comes from modeling the physical world, where you periodically need to create a new volume because the previous volume filled up. In the context of managing electronic records, volumes have limited usefulness, but in certain circumstances, they can be used to help aggregate records based on a time interval between creating new volumes.

Because creating new volumes must be managed either manually or through a custom application, there are other approaches to aggregating records that might be more suitable, depending on the business requirements for disposition.

|

Volumes are automatically named, based on the parent folder name and a sequential numbering scheme to uniquely identify each volume in a given folder. You cannot explicitly assign or change the name of a volume.

Records

A record object consists of a reference to the information or objects that must be managed as a record, and it stores specific metadata about that information. A record can inherit part of its behavior from the container in which it is filed. For example, it is controlled by the disposition schedule of the parent container. For Base and DoD data models, records can be declared in record categories, records folders, and volumes.

IBM Enterprise Records supports both electronic and physical records:

Electronic records An electronic record is a record that points to an electronic document stored in the IBM Content Manager repository. You can create a separate record for each version of an electronic document or a single record for a collection of document versions (using the Declare Versions as Record option within Workplace).

Physical records (markers) A physical record in Enterprise Records Manager (commonly referred to as a marker) is a pointer to a physical document or another object that exists in the organization, such as paper records, tape, or microfilm. This pointer is used to store metadata about the physical object. You can store physical records in any type of record folder.

However, with the exception of electronic folders, a physical record can be declared in only one container (a hybrid folder, a physical folder, or a box). That is, when a physical record is declared in a hybrid folder, physical folder, or box, you cannot file the record into another container unless the container is an electronic folder. This constraint models the physical storage for the record (for example, if you have a paper file, you can physically store it in only one box).

Figure 3-8 on page 88 illustrates the constraint relationship among file plan container entities and records.

Figure 3-8 Constraint relationships among file plan elements

The file plan elements provide a flexible model in file plan design, but having this flexibility also raises the question of when to use folders and when not to use them. In the Base and DoD data models, records can be filed directly in a category container without using records folders. If you need to comply with a particular standard, you must adhere to what it dictates. If you do not need to adhere to specific standards, we recommend that you use a more pragmatic approach to simplify the file plan design and make it more manageable. In essence, design your file plan based on the types of records that you need to declare, their relationships to other records, and the type of disposition.

3.5.2 Attributes of containers and records

Record categories, records folders, volumes, and records have various attributes (properties) that can be used to help identify, characterize, and organize these elements in the file plan. In addition, folders and records can be subclassified to allow for variations, depending on business requirements, and to facilitate the addition of custom properties that further help to organize and manage these file plan elements. In this section, we highlight a few of the common or noteworthy attributes.

Categories, folders, and records have several common predefined string properties that can be used to identify and describe each element:

•Name or title

•Unique identifier

•Description

•Subject

Physical records or boxes might have a unique bar code value as an attribute to uniquely identify each item. The system also maintains a variety of date properties, such as Date Created, Date Opened, and Date Closed, to help manage and track the elements in the file plan. These properties are just a few examples. In subsequent chapters in this book, we describe several of these properties and how they are used.

For more information about the attributes of containers and records, see the software documentation in online help.

Vital records

Vital records are essential records needed to meet operational responsibilities during an emergency or disaster. Therefore, you need to periodically review these records. To ensure periodic reviews of these records, you mark a record category, record folder, or volume as Vital, and all records created under these containers are treated as vital.

When you mark a container as Vital, you select the recurring event that triggers the periodic review or update of vital records, and the action to launch when the review event occurs. Whenever the recurring review event occurs, the vital records’ review workflow that is associated with the event is launched.

Enterprise Records provides a report, Vital Records Due for Disposal, that lists the electronic vital records due for disposition within a specific period.

Permanent records

A permanent record is a record that has been identified as having sufficient historical or other value to warrant continued preservation by your organization beyond the time that your organization is normally required to retain a record for administrative, legal, or fiscal purposes. It has a retention period of permanent and is identified as Permanent on the records retention schedule.

You can mark a record as permanent by setting the value of its Permanent Record Indicator property to True. By default, this property does not display in the Enterprise Records application.

You can also mark containers as Permanent. There is no behavior associated with the Permanent Record Indicator property. That is, the property is informational in nature.

3.6 Case study: File plans in IBM Enterprise Records

Throughout this book, we use two case studies as examples to illustrate some of the options of implementing a file plan in Enterprise Records.

In our first example, the retention rules for a multinational financial institution take into consideration varying retention requirements for records.

In Enterprise Records, a basic disposition schedule is used to illustrate the record level aggregation that is described in Chapter 14, “File plan case study” on page 295. Record category is used to represent the implementation of functional level, such as accounting, broker-dealer transactions, corporate governance, insurance, and annuity.

|

Note: Basic disposition schedule is a high-performance schedule function that is intuitive to use.

|

Within each category, the records can be further broken down into smaller groupings. A basic schedule with immediate destroy without review by an administrator is shown in the case study. Records are destroyed after the review period expired for event-based client.

In our second example, a government agency, depicts single country and single jurisdiction. Region-specific retention requirements do not need to be considered, because retention requirements are governed at the national (federal) level. The government example has mostly case-based records groupings. We use Enterprise Records Advanced schedules to illustrate disposition in Chapter 16, “Advanced disposition case study” on page 327.

|

Note: An Advanced disposition schedule offers more capabilities and flexibility, but it is more complex and might affect performance.

|

In our government example, record categories such as Financial Management, Equipment and Store, and Compensation are represented at the functional level.

Within each category, records are broken up into further groupings for access and ownership purposes.

Disposition takes place at the folder level, such as Agreements. All of the records that pertain to the same contract or agreement are disposed of at the same time (seven years upon expiration of the agreement, for example). Records that are eligible for disposition are grouped for review.

In Chapter 16, “Advanced disposition case study” on page 327, the government case study illustrates review and destroy for one record series and review and either destroy or transfer for client for another record series.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.