6

Conducting the Performance Appraisal Meeting

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Apply effective interviewing skills to the face-to-face performance appraisal meeting between managers and employees.

• Identify key areas to be covered in a performance appraisal meeting.

• Overcome typical performance appraisal meeting pitfalls.

• Conduct negative appraisal meetings.

• Effectively conclude the appraisal meeting.

I once polled a group of more than one hundred middle managers from several work environments on their views concerning the face-to-face performance appraisal meeting. One of the questions I posed was: “On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 representing “very comfortable,” 5 signifying “reasonably comfortable,” and 1 meaning “extremely uncomfortable,” how would your rate your level of comfort in conducting face-to-face performance appraisal meetings with your employees?”

Only four respondents said they were very comfortable conducting appraisal meetings; seven managers answered with a “1.” Since the majority fell into the “reasonably comfortable” range, I followed up with the logical question of why they answered the way they did. More specifically, I asked these managers what made them uncomfortable about conducting face-to-face performance appraisal meetings. Their reasons included: “It’s hard to tell someone the truth about their performance when it’s negative;” “I don’t want to be the bad guy;” “I never know what to say;” “What’s the point? All that really matters to them is how much of a raise they’re getting” and “Employees know how they’re doing—I don’t need to point out the obvious.”

It is hard to argue with the logic of these statements, but it does not have to be this way. Managers can learn to view performance appraisal meetings as a means to an end: that is, as a way for employees to improve their skills and for both parties to enhance employer-employee relations. The way to do this is for managers to increase their comfort level with the interview process by learning and applying effective interviewing skills, becoming familiar and comfortable with areas to be covered, identifying and avoiding common pitfalls, and knowing how to end the meeting. For some managers, the most important step toward increasing one’s comfort level with the interview is to become more skilled at conducting negative appraisal meetings.

EFFECTIVE INTERVIEWING SKILLS

Becoming comfortable with conducting face-to-face performance appraisal meetings begins with successfully applying effective interviewing skills.

Setting the Stage

Setting the stage for the face-to-face appraisal meeting between managers and employees is beneficial to both groups in that it ensures coverage of all the necessary meeting components and assures employees of a comprehensive exchange of information.

While both parties obviously know why they are meeting, the manager’s opening remarks set the tone for what follows, as well as alerting the employee as to what he or she can expect over the next hour or so. Here are two examples of how a manager might begin:

• “Hi, Frank; have a seat. I’m glad you’re here; I’m looking forward to talking with you about your performance over the past year. We’ll also look at some of your goals for the upcoming year. This is your review, Frank, so please feel free to comment or ask questions at any point. Ready?”

Think About It…

Think About It…

On a scale of 1–10, with 10 representing “very comfortable,” 5 signifying “reasonably comfortable,” and 1 meaning “extremely uncomfortable,” how would your rate your level of comfort in conducting face-to-face performance appraisal meetings with your employees?

__________________________________________________________________________

Why?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

• Good morning, Frank. Please, have a seat. I trust you’ve completed your self-appraisal, as requested. I have my review of your work over the past year, which I’ll be comparing with your self-review. In keeping with our 360-degree appraisal approach, I also have input from some of your colleagues and clients with whom you regularly work, which we’ll review. After that, we’ll discuss how successful you’ve been in meeting the goals we agreed to the last time we met, as well as new performance goals and your career aspirations. I invite you to comment or ask questions along the way. Let’s begin, all right?”

As you can see, the manager’s opening remarks in these two examples suggest two entirely different approaches. The manager in the first example has a casual style, setting the stage for an informal meeting. Our second manager is more reserved, suggesting a more structured, formalized meeting. Both approaches have accomplish the desired goal: that is, to let employees know what to expect.

Different Types of Interview Questions

Practicing effective interviewing skills includes the ability to differentiate between types of interview questions and knowing when to use one over the other. (See Exhibit 6–1.)

Competency-Based Questions

Competency-based questions focus on specific examples drawn from four key categories: tangible or measurable abilities, knowledge, behavior, and interpersonal skills. Most jobs emphasize one category over the other, but every employee should be able to demonstrate competencies in all four categories to some extent.

When asking competency-based questions during a performance appraisal meeting, managers should focus on relating specific past job performance to probable future on-the-job behavior. For example: “Kay, as we’ve discussed on several occasions, you’ve had a great deal of difficulty meeting deadlines; put in more general terms, you’ve had trouble with time management. Let’s talk about a specific instance when you had plenty of advance notice as to when a project was due, but still couldn’t complete it on time. What do you think went wrong?” (Allow the employee ample time to respond fully.) Now continue by saying, “Let’s look ahead: imagine receiving that exact same assignment next week. What would you do differently? That is, what technical abilities, knowledge, behavior, and interpersonal skills can you draw upon to ensure timely completion?” As the employee talks, the manager should jot down notes, effectively developing a time management plan for the employee to implement. This can become part of the employee’s future performance goals.

Think About It…

Think About It…

Indicate the style you prefer when making opening remarks: _____ casual _____ formal

Do you think your style could have an impact on the outcome of the performance appraisal meeting? _____ yes _____ no. Explain your answer.

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

xhibit 6–1

xhibit 6–1

Different Types of Interview Questions

Competency-Based Questions:

Focus on relating specific past job performance to probable future on-the-job behavior.

Open-Ended Questions:

Require full, multiple-word responses, lending themselves to discussion.

Hypothetical Questions:

Based on anticipated or known job-related tasks.

Questions are phrased in the form of problems and presented to the employee for solutions.

Probing Questions:

Allow managers to delve more deeply for additional information.

Best thought of as follow-up questions, they are usually short and simply worded.

Close-Ended Questions:

May be answered with a single word—generally “yes” or “no.”

Can give the manager greater control, put certain employees at ease, are useful when seeking clarification, are helpful when you need to verify information, and usually result in concise responses.

Open-Ended Questions

By definition, open-ended questions require full, multiple-word responses. Open-ended questions generally lend themselves to discussion and result in information upon which the manager can build additional questions. They encourage employees to talk, thereby allowing the manager to actively listen and assess both verbal and nonverbal responses. Open-ended questions are particularly helpful in encouraging shy or quiet employees to talk without the pressure that can accompany competency-based questions requiring specific examples.

In performance appraisal meetings, open-ended questions are especially productive during that portion dedicated to discussing future goals and career development. Here are two samples:

• “You’ve certainly succeeded in meeting all of the goals set at our last appraisal meeting. Building on those successes and looking ahead, what performance objectives do you see yourself achieving over the next year?”

• “Let’s talk a bit about your future goals. I know you’ve been taking computer classes at our local community college; how do you see computers fitting in with your career plans?”

Hypothetical Questions

Hypothetical questions are based on anticipated or known job-related tasks. The questions are phrased in the form of problems and presented to the employee for solutions. These questions allow for the evaluation of reasoning abilities, thought processes, attitudes, creativity, work style, and one’s approach to different tasks.

Let’s consider this example from an appraisal meeting during which the employee, currently a first-line supervisor, expresses an interest in furthering her career by becoming a manager. You have a complete understanding of how well she performs in her current capacity, but need more information about how she is likely to deal with managerial responsibilities.

Here is a relevant hypothetical question: “If you were a manager, and your team complained about having to meet some rather unreasonable demands from one of the company’s top clients, how would you go about satisfying both the client and your staff?”

Probing Questions

These are questions that allow managers to delve more deeply for additional information. Best thought of as follow-up questions, they are usually short and simply worded. Probing questions are appropriate when discussing past performance, previously set objectives, new performance objectives, and career development plans. Here are some examples:

• “You mentioned that the last project you participated in didn’t turn out the way you’d planned. What happened?”

• “You’ve succeeded in meeting the goals you set last year; what do you attribute this to?”

• “You indicated that you’d like to try your hand at marketing; why?”

• “Who or what has influenced you with regard to your career goals? In what way?”

Close-Ended Questions

These are questions that may be answered with a single word—generally “yes” or “no.” Close-ended questions can give the manager greater control, put certain employees at ease, are useful when seeking clarification, are helpful when you need to verify information, and usually result in concise responses. On the other hand, close-ended questions can result in limited information and should not be used in lieu of competency-based, open-ended, hypothetical, or probing questions.

Here are some examples of functional close-ended questions. In each instance, the response will serve as the foundation for one of the other types of interview questions.

• “Would you say that your rapport with your coworkers has been impacted as a result of your role as team leader on the last project?”

• “Earlier you said that your inability to come in on time is due to the fact that the bus schedule has been changed; have you ever considered taking an earlier bus or using another mode of transportation?”

Exercise: Interview Questions

Exercise: Interview Questions

Consider this scenario: You are meeting with Joe for his annual performance appraisal. Joe has effectively worked as your assistant for the past two years. You have given him an overall rating of “very good”—the second highest possible rating. Joe has expressed an interest in taking on additional responsibilities.

As his manager, identify five questions you would ask Joe during the appraisal meeting:

Competency-based question:

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Open-ended question:

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Hypothetical question:

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Probing question:

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Close-ended question:

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

HINTS, SUGGESTIONS, AND SOME ANSWERS

Competency-based question:

“Joe, taking on additional responsibilities requires good time management skills. Tell me about a specific instance in which you had to juggle multiple assignments, all due at the same time. How did you allocate your time?”

Open-ended question:

“Please describe three of your greatest strengths and how you feel they qualify you for taking on additional responsibilities.”

Hypothetical question:

“Consider this scenario: You’re a supervisor in charge of four employees, two of whom do not get along. Their bickering is impacting productivity and the morale of their coworkers. What would you do?”

Probing question:

“You indicated earlier that you want to return to college; what courses are you interested in taking?”

Close-ended question:

“Based on what you have told me so far, can I assume that your ultimate goal is to become the manager of this department?”

Talking Versus Listening

Managers need to balance the amount of talking they do with listening. Many managers talk too much, erroneously believing that they are more in control of the meeting as long as they are talking. In reality, managers should devote no more than twenty-five percent of the time to talking. Their time should be spent highlighting and asking questions about the employee’s past performance and success in achieving previously set performance objectives. In addition, they should ask questions about the employee’s new performance objectives and career development plans. The remaining seventy-five percent of the meeting should be devoted to listening to the employee.

Guidelines for effective listening include:

• Listening for connecting themes to enable you to concentrate on key job-related information

• Summarizing periodically to ensure a clear picture of what the employee is telling you

• Filtering out distractions to avoid missing important information

• Using information as the basis for additional questions

• Screening out personal biases

• Acknowledging any unusual emotional states that could influence your ability to concentrate

Exercise: Talking Versus Listening

Exercise: Talking Versus Listening

Imagine conducting a performance appraisal meeting with an employee who, while competent, is not very interesting to listen to. He speaks in a monotone, and tends to ramble. What listening guidelines could you apply that would enable you to focus and more actively listen?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Body Language

Managers and employees can learn as much about one another through their body language as from verbal messages. On the other hand, nonverbal messages are easily misinterpreted, generally when body language is interpreted according to the other person’s own gestures or expressions. For example, just because you have a tendency to avoid eye contact when you are hiding something does not mean that an employee is avoiding your eyes for the same reason.

Each of us has our own pattern of communicating nonverbally. This includes facial expressions, body movements and gestures, as well as pauses in speech, rate of speech, vocal tone, pitch, and enunciation. Together, all of these factors “speak” to another person from the very first moment of contact. Often the message can be confusing. For example, body movements such as finger or foot tapping can contradict facial expressions such as smiling. The situation may be further complicated when the manager tries to assess the content of what is being said. The conflict between the verbal and nonverbal message can be confusing, leaving the manager wondering which message is more accurate. Here is a tip: Since verbal messages are clearly easier to control than nonverbal ones, when there is a conflict between the verbal and the nonverbal, the nonverbal is often more persuasive. This may be helpful, however, only to the extent that the person’s nonverbal messages are being interpreted accurately.

During a performance appraisal meeting, a manager should strive to accomplish three goals:

1. To convey positive body language by exhibiting gestures and movements that are typically interpreted as positive, such as leaning forward in one’s seat when the other person is speaking.

2. To project consistency between verbal and nonverbal messages by focusing on using clear language supported by typically interpreted gestures. For example, if a manager wants to express encouragement, she could say, “I think your goal of becoming a supervisor is achievable; let’s talk about what you need to do to get there.” At the same time, she could maintain direct eye contact, smile, and sit up straight in her chair, appearing ready to discuss the employee’s interest in upward mobility.

3. To accurately assess nonverbal messages conveyed by the employee by looking for individual patterns. For example, the employee who rubs his eyes every time you broach the subject of how he is doing with a current long-term project, is conveying a pattern that suggests something is amiss. It is likely that this individual rubs his eyes whenever he is uncomfortable or feels he is being pressed to discuss something he would prefer to avoid. This pattern alerts you to the fact that you need to probe deeper and persist until you determine what is really going on.

Let’s look at a scenario that encapsulates these three objectives: Liz is meeting with her manager, Anne, to discuss her annual performance appraisal. A preliminary examination of her review reveals what she expected: consistently high ratings in every category. As Anne delves into the details of each area her body language is supportive and encouraging, including direct eye contact and leaning forward. When Liz speaks Anne nods, indicating understanding. When it comes time to discuss Liz’s future aspirations, Anne listens carefully then says, “I hear what you’re saying Liz, about wanting to continue growing in your current position, but I can’t help but wonder if there isn’t something more you’d like to strive to accomplish.”

Anne is responding to the inconsistency between Liz’s body language and her words. She is specifically responding to the fact that she began shifting in her seat and hunched over when the subject turned to her career objectives. Anne does not assign a specific meaning to either movement; however, the sudden change in Liz’s body language sends a message to Anne that something is amiss. Sure enough, Liz straightens up in her seat and cautiously begins to describe her ultimate career goal. Anne is careful to convey positive body language coupled with encouraging verbal language as Liz gains greater confidence and reveals more details about her dream job.

AREAS TO BE COVERED

The performance appraisal meeting should focus on four key areas: past performance, previously set performance objectives, new performance objectives, and the employee’s career development plan. Stated another way, two areas of focus have to do with what has already taken place, and the other two areas have to do with what is yet to come. Throughout the process, the manager’s role should be that of a facilitator.

Think About It…

Think About It…

How do you convey the following messages nonverbally?

Concern: _________________________________________________________________

Disagreement: _____________________________________________________________

Disapproval: _______________________________________________________________

Disbelief: __________________________________________________________________

Encouragement: ____________________________________________________________

Frustration: _________________________________________________________________

Interest: ____________________________________________________________________

Sincerity: ____________________________________________________________________

Support:

Do you think your nonverbal messages are clear and accurately interpreted?

_____ yes _____ no

Do you consciously strive for consistency between your nonverbal and verbal messages?

_____ yes _____ no

Do you think you know your employees well enough to be able to assess their nonverbal messages accurately?

_____ yes _____ no

Past Performance

Many managers erroneously believe that past performance should receive the greatest degree of attention in the appraisal meeting. Indeed, some managers view this as an opportunity to dwell on what the employee has done wrong. However, talking about past performance should take the least amount of time. If the manager is performing his or her coaching and counseling duties effectively throughout the year (Chapter 2), then nothing said during the appraisal meeting will come as a surprise to the employee. The employee should essentially know from the outset how he or she is going to be evaluated.

The manager can use the appraisal meeting as an opportunity to enhance his or her review with input from the employee via a self-evaluation, and/or supplemental information from others as a result of a 360-degree review (both discussed in earlier chapters). This, in turn, should result in a two-way dialogue, with the employee being encouraged to ask questions and freely express himself or herself, both verbally and nonverbally. This dialogue should conclude with a summary of the employee’s past performance and the employee’s signature on the evaluation form signifying understanding of the contents and not necessarily agreement.

Previously Set Performance Objectives

Discussing how successful the employee has been in achieving previously set performance objectives is the next step in the appraisal meeting. As with past performance, if the manager has done his or her job throughout the year, the employee will have a clear sense of how successful he or she has been in meeting his or her goals prior to this meeting. Presumably, the two will have sat down together at given intervals to discuss progress and/or problems encountered. Perhaps the original goals were adjusted upward or downward. In any event, employees should arrive at these meetings knowing how successful they have been in achieving past goals; what problems, if any, they encountered in their quest to satisfy their goals; and how the manager views their accomplishments. This portion of the meeting is a recap, essentially serving as a foundation for setting new performance objectives.

Think About It…

Think About It…

If you were an employee on the receiving end of a performance appraisal, how would you feel if your manager dwelled on past performance and previously set performance objectives?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

New Performance Objectives

New performance objectives should be predicated on how successful the employee has been in accomplishing past performance objectives. The goal, however, is not necessarily to achieve more or to work harder. Sometimes, new objectives take the employee in an entirely different direction.

To illustrate, Nicholas is a sales agent who increased revenues in his division by twenty-five percent. Since his target was twenty percent, no one would argue that Nicholas had succeeded in meeting his previously set performance objectives. Now it is time for Nicholas to work jointly with his manager to set new performance objectives. At first glance, it might seem logical to suggest that Nicholas strive to increase sales by thirty to thirty-five percent, but that is not what he wants. For the next review period, Nicholas would like to set his sights on becoming more creative in his sales approach. This is slightly problematic as it is not as quantifiable; yet, it is clear that this performance objective will satisfy Nicholas’ drive to grow in his job.

Together, Nicholas and his manager should identify a plan for achieving this objective. Here are the steps they will need to take, accompanied by examples of what Nicholas might consider:

1. Clearly state the performance objective. For example: “To become more creative in my sales approach.”

2. Break it down into identifiable and manageable components. For example: “To identify and explore various methods for closing deals, to observe other sales approaches first-hand, to practice various sales approaches in a simulated environment, and to isolate those sales approaches that will generate increased sales.”

3. Assign resources needed to accomplish each component. For example: “Read periodicals and have conversations with other sales agents will help me explore new methods for closing deals, accompanying other agents on sales calls will enable me to observe varying sales approaches first-hand, having access to a “practice” environment with colleagues present will allow me to experiment with different sales approaches, and talking with my manager about creative sales approaches that will also generate increased sales will help me pinpoint those new approaches that are likely to lead to the achievement of my goal.”

4. Identify possible barriers. For example: “Lack of willingness or availability of other sales agents who can demonstrate different sales approaches, lack of a simulated environment in which I can practice and colleagues willing to provide feedback, and my inability to couple creative approaches with increased sales.”

5. Develop a timeline that will include periodic meetings between Nicholas and his manager. For example, assuming the initial meeting between Nicholas and his manager takes place on February 15, on March 12: “Meet with my manager to report on what I’ve learned about different methods for closing deals; on April 30, meet to summarize my first-hand observations of other sales approaches; on May 5, practice various sales approaches in a simulated environment with colleagues present to provide feedback; on May 21, meet with my manager to identify those sales approaches that we jointly determine will likely generate increased sales while allowing me to be more creative in my approach.”

Remember, the manager’s role throughout this process is that of a facilitator. He or she can ask questions and make suggestions, but the employee needs to do most of the planning and work.

Career Development Plans

This is the last stage of the appraisal meeting and in many respects the most rewarding. Savvy managers understand the importance of keeping employees motivated (Chapter 7); developing a career plan as part of the appraisal process is one key way of accomplishing this goal.

For maximum results, this stage requires four steps:

Step One: Toward the end of the appraisal meeting, the manager should initiate a discussion about the employee’s career objectives. He or she should listen, encouraging the employee to be as specific as possible. The manager should not try to discourage the employee or suggest that the goals are unrealistic or unachievable.

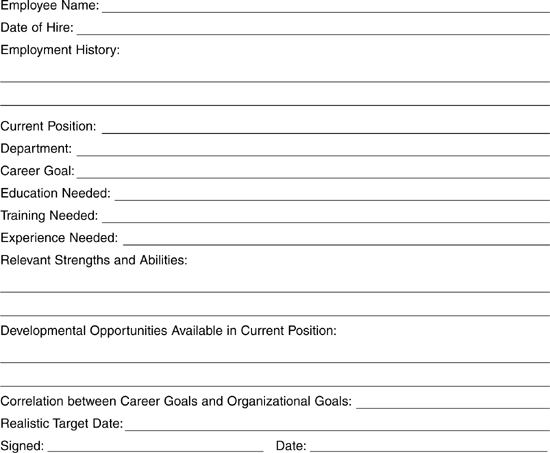

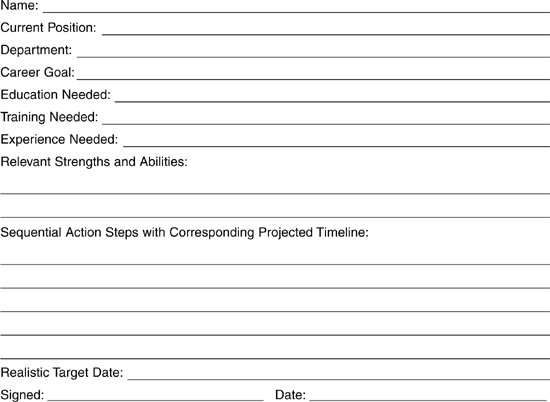

Step Two: The manager should next produce two forms (Exhibits 6–2 and 6–3): one for the manager to complete and the other for the employee to complete. Each of them will fill out their respective form and bring it with them to a follow-up meeting, usually scheduled for one to two weeks later.

What is likely to happen if an employee’s career goals are contrary to organizational goals? For instance, could this lack of compatibility impact productivity?

__________________________________________________________________________

What is likely to happen if a manager does not think an employee’s goals are achievable? For instance, could this result in an adverse impact on employer-employee relations?

__________________________________________________________________________

What is likely to happen if a manager seriously disagrees with any of the sequential action steps and projected timeline identified by the employee? For instance, could this result in frustration on the part of the employee and possibly result in his resignation?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Step Three: The manager and employee will together review the forms each of them has completed, discussing areas in which they agree and disagree.

Step Four: Together, the manager and employee will identify practical steps for implementation in relation to the employee’s current job and role in the organization.

TYPICAL PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL MEETING PITFALLS

Even when they have meticulously prepared a written review including ratings that are backed by specific examples, managers can find themselves influenced by factors during the appraisal meeting to the extent that they may be inclined to change their original evaluations. Once made aware of some of these pitfalls or traps, however, managers are less likely to be influenced to change their original assessment. Managers need to be aware of these tendencies throughout the performance appraisal process, keeping them in mind both before and during face-to-face meetings.

Perhaps the most influential factor of all is past performance. Managers can be easily influenced by good past performance to the extent that they assume it will always continue. Hence, performance “glitches” tend to be rationalized and overlooked. On the other hand, poor past performance can detract from improved performance, causing managers to discount steps toward improvement.

An offshoot of the good/bad past performance issue is the recency factor. As we discussed in Chapter 5, the recency factor operates when a significant positive recent accomplishment stands out, overshadowing an otherwise extensive pattern of poor performance. Likewise, a recent error tends to stand out in the manager’s mind, overriding a year’s worth of steady performance.

Sometimes, too, managers fall into the trap of comparing employees with one another, thereby granting the “best” of the group the highest possible rating. In reality, that person’s performance may warrant no more than an above average rating, and the others somewhat less. In addition to failing to review employees’ performance accurately, this manager will have departmental-wide performance issues.

The “blind spot syndrome” can also be problematic when it comes time to conduct an appraisal meeting. Here, the manager excuses those employee’s shortcomings that are similar to his or her own. Evaluating the employee honestly would mean confronting one’s own deficiencies—something many of us have difficulty doing.

Managers may also have an unofficial “don’t like” list that they subconsciously refer to when conducting appraisal meetings. Included on this list are: employees who fail to meet their own personal standards, despite the fact that they meet those set in the job description; employees who challenge or disagree with them; employees who are too independent (or too dependent, whichever the perceived case may be); personality traits decidedly different from their own or the department’s “superstar”; and employees whose style differs from their own when they performed that job.

Here are some additional common pitfalls that managers should avoid when conducting performance appraisal meetings:

• Becoming defensive or argumentative.

• Discussing personality traits and attitudes.

• Interrupting the employee as long as he or she is saying something relevant.

• Asking leading questions, such as “Don’t you think…?”

Think About It…

Think About It…

What trap(s) have you fallen into when conducting performance appraisal meetings?

__________________________________________________________________________

If you have never conducted an appraisal meeting before, what trap(s) do you see yourself as being most vulnerable to?

__________________________________________________________________________

What steps will you take in the future to avoid these traps when conducting appraisal meetings?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

• Expressing opinions, impressions, and feelings as opposed to sticking with the facts.

• Solving the employee’s problems for him or her.

• Making statements such as, “If I were you…”

• Engaging in superficial discussions.

• Talking about oneself.

• Talking down to the employee.

CONDUCTING NEGATIVE APPRAISAL MEETINGS

As mentioned in Chapter 4, no one will dispute that it is difficult to tell an employee that their performance is unsatisfactory. Many managers avoid what they perceive to be an inevitable confrontation and opt, instead, to tell the employee that his or her work is satisfactory. They do this, hoping that:

• The employee’s performance will improve.

• The employee will transfer or terminate.

• The manager will be promoted and the employee will become someone else’s “headache.”

In reality, poor performers rarely improve without the coaching and counseling of their managers. Instead, what frequently happens is something like this:

Lucy’s job performance is borderline satisfactory. Her manager, Victor, tells her that her work is “good,” and gives her a raise. Lucy keeps performing at the same level, either not knowing or caring that her work has really slipped into the category of “unsatisfactory.” Victor avoids any coaching or counseling opportunities throughout the year, hoping Lucy will quit but she doesn’t. Her annual review rolls around and Victor repeats last year’s scenario: he tells her that her work is “good” and gives her another raise. Another year goes by and Victor grows increasingly annoyed with Lucy (and himself for not confronting her), and finally explodes. He calls HR and says that he wants Lucy fired. HR pulls her file and finds a stack of performance appraisals that say her work is good, accompanied by a record of pay increases. HR informs Victor that there is no documentation to support his request to terminate her and that he will have to now begin doing what he should have done three years ago: coach, counsel, and document.

Does this scenario sound familiar to you? Scenarios like this can be avoided in a relatively painless way by following these guidelines:

1. Be honest.

2. Support your statements with facts.

3. Avoid opinions or subjective language.

4. Never personalize any situation.

5. Document everything, both negative and positive.

6. Don’t wait a year to tell employees that their work is unsatisfactory.

7. Give employees the benefit of the doubt—initially.

8. Make clear that the expectations you are citing are job-related and not yours personally.

9. Don’t expect gratitude.

10. Be honest (it’s worth repeating).

Exercise: Conducting a Negative Performance Appraisal Meeting

Exercise: Conducting a Negative Performance Appraisal Meeting

Following is a partial performance appraisal meeting between Bob, a chief engineer, and Al, his general manager. After reading the excerpt, apply the guidelines listed above and on the previous page to Al’s handling of his meeting with Bob and answer the questions that appear at the end.

Al: |

Bob, I asked you to come in because this is the time of year when I have to evaluate your performance for the past year. I have your performance appraisal in front of me, and I want to tell you what I think of how you’re doing. Let me review some of the good points first. |

Bob: |

That’s always a good place to start and end, as far as I’m concerned! |

Al: |

One of the items that I have rated you on is customer relations with respect to design and application, and I’ve checked you off here as outstanding. |

Bob: |

No arguments from me on that one! |

Al: |

The reports from our customers have been full of praise about the kind of help you’ve given them. I have also rated your technical abilities as outstanding. This is reflected by the high quality of design work that leaves your department, and by the help you’ve given me on difficult engineering problems. |

Bob: |

I do my best, Al, you know that; I always do my best. |

Al: |

Yes, well, um, yes. O.K. I need to, that is, we need to look at the other side of the coin for a moment. One of the most important reasons for getting together today is that I need to tell you about some of your weaker points. |

Bob: |

Weaker points? |

Al: |

I know you have it in you to overcome these weaknesses, so let’s cover some of them. |

Bob: |

Some of them? How many are there? |

Al: |

Oh, that’s just an expression. Nothing to worry about. |

Bob: |

Uh huh… |

First, I’m a little concerned about the lack of supervision you’re providing for your three section heads. |

|

Bob: |

What do you mean? |

Al: |

I’ve heard some things… well, you know, people talk; but I’ve also looked at the records and noticed a marked increase in turnover within your department. And Joanna, one of your top section heads, has been approached by another firm and is probably going to accept their offer. |

Bob: |

Yes, that’s true. Joanna feels sort of stuck here and is not getting the kind of opportunities she’d like; she’s bright and ambitious; can’t say that I blame her. |

Al: |

Well, Bob, maybe it’s more than that. Maybe she’s not motivated. It’s your responsibility to find things that will interest her. |

Bob: |

I see Joanna everyday. We talk about the work she’s doing and how she’s doing it. I don’t have time to get inside her head and figure out what will make her happy. That’s her job. Any other complaints? |

Al: |

Well, actually, I’ve heard that you don’t get involved enough with any of your section heads. |

Bob: |

My door is always open. They know that. And so do you. But I don’t have time to hold hands. |

Al: |

Is that why you didn’t help Joe when he came and told you he didn’t think he could make his last deadline without additional help? |

Bob: |

If Joe isn’t sharp enough to figure out how to meet his deadline he shouldn’t be in that job. I always managed when I was in that job; he should be able to also. It’s not all up to me. |

Al: |

No, of course not. I didn’t mean to imply that it was. I’m just pointing it out as one of my areas of concern about your performance. I feel that this problem you have with communication and employer-employee relations is contributing to the increase in turnover and low morale in your department. |

Bob: |

Hold it! Now you’re telling me I’m a lousy boss and I’m responsible for people leaving and being down in the dumps because they can’t cut it? |

Al: |

That’s not what I said. Not exactly, anyway. I’m trying to help you out here, Bob, and you’re turning on me. |

Bob: |

Let’s just cut to the chase, Al; what’s the bottom line here? |

Al: |

Bottom line? |

Bob: |

Yeah, my rating; that’s why I’m here, isn’t it? |

Uh, yes, yes… it is. Well, what do you think? |

|

Bob: |

What do I think? |

Al: |

Yes, about your overall rating… what do you think you should get? |

Bob: |

I’m the first to admit there’s room for improvement; so I’ll hold off on saying I’m outstanding and say my overall rating should be “very good.” |

Al: |

Interesting. |

Bob: |

What are you giving me Al? |

Al: |

Ah, well, after listening to what you’ve said, I can see why you feel a “very good” is appropriate. |

Bob: |

You weren’t going to give me less than that, were you Al? |

Al: |

I think we can end this on a positive note, Bob. Let’s agree that you’re going to work on your people skills and try to reduce turnover. |

Bob: |

How? |

Al: |

We can talk about that another time; you know, give it some thought and come up with a plan that we can go over. You’re an asset to this company, Bob. |

Bob: |

An asset with weaknesses? |

Al: |

That’s a funny way of putting it; everyone has areas that need work, right? |

Bob: |

Yeah; some more than others, right? There’s one thing I’ve got to ask you Al; why did you wait until now to tell me these things? |

Al: |

This is your annual performance appraisal, Bob; I’m supposed to tell you now; besides, be honest—you knew what I was going to talk about, didn’t you? In any event, I’m glad you came in this morning; I hope you’ve found this session helpful; let’s get together again in the next few weeks… |

Bob: Sure, Al; I can’t wait.

Was Al honest with Bob? _____ yes _____ no

Did Al support his statements with facts? _____ yes _____ no

Did Al personalize the situation? _____ yes _____ no

Did Al have documentation? _____ yes _____ no

Did Al make a mistake in waiting until the appraisal to tell Bob that aspects of his work were unsatisfactory? _____ yes _____ no

What, if anything, might Al have done differently?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

HINTS, SUGGESTIONS, AND SOME ANSWERS

Was Al honest with Bob? Al was honest with Bob as he accurately conveyed the praise Bob had received from customers. He was also somewhat honest when he began discussing Al’s failure to provide adequate supervision to his three section heads. The problem was he was relying largely on hearsay information.

Did Al support his statements with facts? Al became flustered when Bob challenged his statements. As such, Al resorted to making assumptions, offering suggestions, and citing generalizations.

Did Al personalize the situation? Al allowed the meeting to become emotional and personal. For example, when Bob became upset by Al’s suggestion that employees were leaving because of his poor communication skills, Al said, “I’m trying to help you out here, Bob, and you’re turning on me.”

Did Al have documentation? Al’s information was based primarily on hearsay.

Did Al make a mistake in waiting until the appraisal to tell Bob that aspects of his work were unsatisfactory? Yes. Nothing that is said during a performance review should come as a surprise to the employee.

What, if anything, might Al have done differently? (1) He should have communicated concerns about Bob’s work prior to the review; (2) he should have supported his statements with facts; (3) he should have had specific, concrete documentation reflecting Bob’s performance; (3) he should have remained impartial and neutral; (4) he could have allowed Bob to complete a self-appraisal so they could discuss any differences in their respective evaluations; (5) he should have maintained the confidentiality of other employees.

CONCLUDE THE MEETING

Generally speaking, performance appraisal meetings should last anywhere from forty-five to ninety minutes. You will need this amount of time to discuss four main areas: past performance, previously set performance objectives, new performance objectives, and the employee’s career development plan. It may be tempting to end a performance appraisal meeting sooner than you should, especially if the employee and the manager see eye-to-eye on everything or if the employee is disagreeable and the manager wants to avoid a confrontation. Apply the following checklist before concluding the appraisal meeting and you will find that there is plenty to cover with every type of employee.

Manager’s Checklist

Managers are advised to have a checklist identifying what needs to be covered in the appraisal meeting before concluding (Exhibit 6–4).

1. Did I summarize past performance? While the appraisal form probably has an overall rating that summarizes your assessment of the employee’s past performance, it is still advisable to verbalize your evaluation. Here are some sample summarizing statements:

• “Joan, in summary, I’d like to reiterate how pleased I am with your overall work performance. You exhibit a fine work ethic and are especially impressive when motivating your team to meet deadlines.”

• “Rich, we’ve spent a good deal of time talking about your need to improve with regard to accuracy in your work. You’ve identified some specific steps that you’re going to implement, and we’ve agreed on a schedule of meetings to discuss your progress. I’m confident that you’ll succeed.”

2. Did I review previously set performance objectives? Determining whether the employee has succeeded in meeting previously set performance objectives will enable you both to move forward in setting new objectives. Ask yourself: Were the previous goals realistic? Achievable? Sufficiently challenging? Interesting for the employee? Consistent with his or her personal goals? Here are some examples of what you can say:

• “Sasha, the manner in which you tackled last year’s goals is truly impressive, and I’m pleased to learn that you found the process to be personally gratifying.”

• “Tiffany, as far as your success in meeting previously set performance objectives is concerned, I’d like to summarize by saying that, despite the fact that you fell somewhat short of your overall goal, you exhibited tremendous effort, and that did not go unnoticed.”

xhibit 6–4

xhibit 6–4

Manager’s Checklist Prior to Concluding the Appraisal Meeting

![]() Did I summarize past performance?

Did I summarize past performance?

![]() Did I review previously set performance objectives?

Did I review previously set performance objectives?

![]() Did we work together to set new performance objectives and agree on follow-up dates to review the employee’s progress?

Did we work together to set new performance objectives and agree on follow-up dates to review the employee’s progress?

![]() Did I work with the employee on a career development plan?

Did I work with the employee on a career development plan?

![]() Did I reinforce praise and end on a positive note?

Did I reinforce praise and end on a positive note?

![]() Did I deliver criticism constructively?

Did I deliver criticism constructively?

![]() Did I encourage the employee to make comments or ask questions?

Did I encourage the employee to make comments or ask questions?

![]() Did I reiterate my availability for help and support?

Did I reiterate my availability for help and support?

3. Did we work together to set new performance objectives and agree on follow-up dates to review the employee’s progress? How well the employee managed to meet past performance objectives sets the stage for future goals. This is a joint effort, and the manager should be able to make a statement similar to the following before concluding the meeting:

• “Lee, I’m pleased with our discussion about your goals for the upcoming year. We have a timeline of interim steps, and we’ll meet to discuss your progress as indicated on that timeline. If you have any questions or concerns prior to our first scheduled meeting, please don’t hesitate to come to see me.”

4. Did I work with the employee on a career development plan? Even the most efficient and dedicated employees are going to feel discouraged if the work they perform does not correlate with their personal career development. Consider this statement before concluding the appraisal meeting:

• “Jack, we’ve agreed to meet in a week to further discuss your career goal of becoming a leading contributor in the marketing department. I’ve given you a career development form to complete, and I’ll do the same. I’m looking forward to helping you achieve your personal objectives while continuing to making a contribution to this organization.”

5. Did I reinforce praise and end on a positive note? Obviously this is easier to do with outstanding employees:

• “Jill, I’d like to conclude by reiterating what I’ve said throughout this meeting: you are an asset to this organization in so many ways, especially in your ability to work under pressure, your willingness to take on additional tasks to help others meet their deadlines, and the accuracy of your work.”

But everyone deserves recognition for whatever it is that they do well. As stated earlier, if there is absolutely nothing you can find to praise, then one has to wonder why the employee is still with the organization. Here is something you can say to an employee with numerous performance issues, but still does some things well: “Justin, despite the areas in which you need to improve, you continue to demonstrate an in-depth knowledge of the technical aspect of your job and that’s impressive.”

6. Did I deliver criticism constructively? Delivering criticism can be less stressful if you strive to be straightforward, are specific, provide a balanced picture, and are encouraging. Here is an example of criticism that is not constructive:

• “Tom, we’ve talked about your failure to focus on details a dozen times. You’re just not getting it. I’m worried that the only way I’m going to get through to you is to write you up as part of our formal disciplinary process. Then maybe you’ll understand how serious this is!”

Here is a more productive approach to constructive criticism:

• “Tom, in summary, we’ve talked about your need to better focus on details. You’ve identified some steps you feel will help you achieve this goal and I support them. Your work in many other areas is commendable; I’m confident that you’ll succeed in elevating the level of your attention to detail if you adhere to the plan you’ve mapped out.”

7. Did I encourage the employee to make comments or ask questions? Performance appraisal meetings consist of two-way communication. Earlier, we discussed the approximate ratio of talking and listening, with managers talking about twenty-five percent of the time. Remind yourself of this figure throughout the meeting and at the end ask yourself how successful you were in affording the employee most of the time commenting or asking questions. Just before ending, say, “Mandy, before concluding our meeting, do you have any additional comments or questions?”

8. Did I reiterate my availability for help and support? Remember that one of your primary responsibilities as a manager is that of a coach, whereby you are available to regularly offer assistance, support, praise, and constructive criticism (see Chapter 2). Reiterating this availability to the employee before ending the appraisal meeting can help to enhance employer-employee relations.

Becoming comfortable with conducting face-to-face performance appraisal meetings begins with successfully applying effective interviewing skills. This includes setting the stage and differentiating among five recommended types of questions: competency-based, open-ended, hypothetical, probing, and close-ended. Each serves a distinct purpose and contributes toward making the performance appraisal meeting maximally productive. Additional interviewing skills include balancing talking with listening and practicing positive body language.

The appraisal meeting should focus on four key areas: past performance, previously set performance objectives, new performance objectives, and a career development plan for the employee. Throughout the process, the manager’s role should be that of a facilitator.

Even when they have meticulously prepared a written review including ratings that are backed by specific examples, managers can be influenced by factors during the face-to-face meeting to the extent that they may be inclined to change their original evaluations. Pitfalls include allowing a recent accomplishment to overshadow an otherwise extensive pattern of poor performance, measuring an employee’s performance against that of other employees rather than the responsibilities and requirements of the job, and excusing shortcomings in the employee that are similar to those of the manager. Once made aware of some of these pitfalls, however, managers are less likely to be influenced to change their original assessment.

No one will dispute that it is hard to tell an employee that his or her performance is unsatisfactory. But poor performers rarely improve without honest input by their managers.

Managers are advised to have a checklist identifying what needs to be covered in the appraisal meeting before concluding. Questions managers should ask of themselves include: Did I summarize past performance? Did we work together to set new performance objectives? Did I reinforce praise and end on a positive note? Did I deliver criticism constructively? And did I reiterate my availability for help and support?

1. Part of the performance appraisal meeting should focus on setting new performance objectives. These should be predicated on:

1. (d)

(a) learning from one’s mistakes.

(b) the overall rating the employee receives.

(c) how much money there is in the department’s training budget.

(d) how successful the employee has been in accomplishing past performance objectives.

2. Having a checklist identifying what needs to be covered can help managers successfully conclude an appraisal meeting. One item on this list concerns the manager’s offer of help and support. This serves as a reminder that one of a manager’s primary responsibilities is that of a:

2. (d)

(a) confidant.

(b) counselor.

(c) therapist.

(d) coach.

3. The number one way to effectively conduct negative appraisal meetings is for the manager to:

3. (b)

(a) have an attorney present.

(b) be honest.

(c) wait till the date of the meeting to spring the news that the employee’s performance is sub-par so he or she cannot mount a defense.

(d) suggest that all is well, hoping that the employee will either improve or terminate.

4. There are a number of appraisal pitfalls managers need to be wary of especially when conducting the face-to-face meeting. Perhaps the most influential factor of all is:

4. (a)

(a) the employee’s past performance.

(b) the employee’s attitude.

(c) future goals of the employee.

(d) the employee’s personality.

5. There are five recommended types of questions to ask during the performance appraisal meeting. The type that focuses on relating specific past job performance to probable future on-the-job behavior is called a(n):

5. (c)

(a) probing question.

(b) open-ended question.

(c) competency-based question.

(d) hypothetical question.